Abstract

Background:

Despite the increased use of percutaneous interventions, infarction-related cardiogenic shock (CS) is still associated with high mortality. Biomarkers might be helpful to identify patients at risk, and point towards novel therapeutic strategies in CS. The phosphaturic hormone fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) has recently been introduced as a predictor for mortality in patients with chronic systolic heart failure. However, its predictive role in CS has not been investigated so far.

Methods and results:

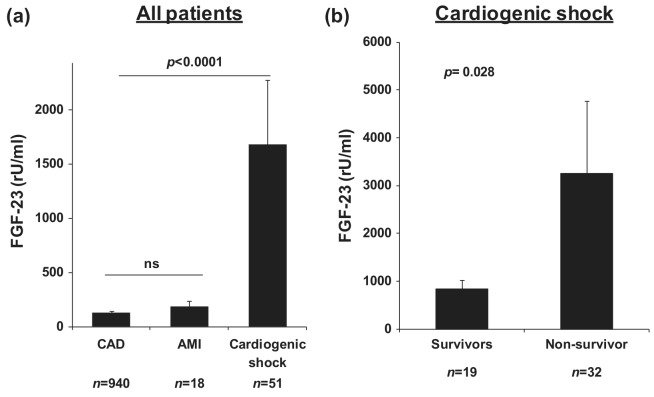

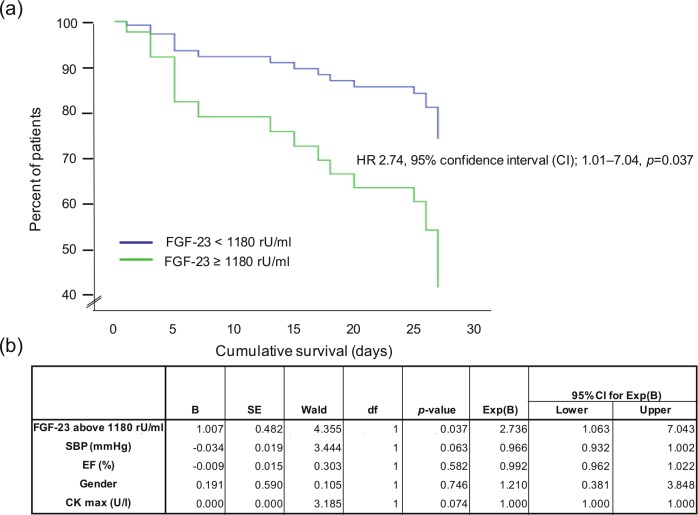

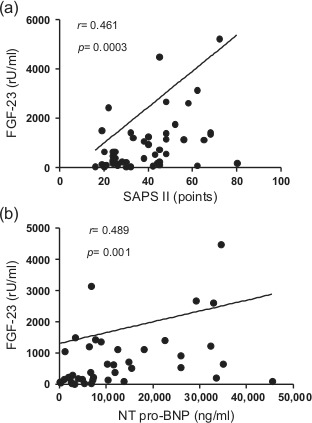

FGF-23 was measured in 51 patients with CS. Eighteen patients with uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and 940 patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing elective coronary angiography included in a previous study served as control groups. Compared with patients with stable CAD, FGF-23 was profoundly elevated in patients with CS, but not in patients with uncomplicated AMI (CAD: 131.1±9.5; AMI: 175.3 ±57.2; CS: 1684.4±591.7 rU/ml, p<0.0001 CS vs. CAD). In patients with CS, FGF-23 correlated significantly with the SAPS II score (r=0.461, p=0.0003) and NT-pro BNP levels (r=0.489, p=0.001). Patients were stratified as “survivors” and “non-survivors” according to their 28-day mortality. The overall 28-day-mortality-rate was 37%. Non-survivors of CS showed significantly higher FGF-23 levels compared with survivors (3260.1±1514.7 vs. 847.9±182.4 rU/ml, p=0.028). In the ROC curve analysis, FGF-23 levels predicted 28-day mortality (area under the curve (AUC) 0.686, p=0.028), and FGF-23 level of 1180 rU/ml was identified as optimal cut-off value. In a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model adjusted for gender, blood pressure, ejection fraction and levels of creatine kinase, FGF-23 levels above 1180 rU/ml significantly predicted 28-day mortality (hazard ratio (HR) 2.74, 95% CI 1.01-7.04, p=0.037).

Conclusion:

In CS, a tremendous increase in FGF-23 occurs, and high levels of FGF-23 are associated with poor outcome.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, FGF-23, outcome predictors

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is one of the clinical entities representing acute heart failure syndromes.1 Despite the broad use of early percutaneous intervention, the mortality rate is still high. Indeed, CS represents the leading cause of in-hospital death in patients with acute myocardial infarction.2-4 A growing body of evidence indicates that CS is not simply a hemodynamic problem caused by severe myocardial ischemia leading to decreased cardiac output. Its complex pathophysiology involves neurohormonal responses, which initiate a downward spiral resulting in tissue hypoperfusion, hypoxemia, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and finally death.5 Identification of markers may contribute to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms and may improve identification of patients at risk, in order to initiate appropriate treatment.

A deranged calcium-phosphate metabolism is associated with various cardiovascular diseases. Epidemiologic evidence suggests an association between hyperphosphatemia and coronary calcification,6,7 cardiovascular and mortality8,9 not only in patients with chronic kidney disease but also in patients with normal renal function. The phosphaturic hormone fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) is produced by osteoblasts and osteocytes.10 It is an important negative regulator of serum phosphate levels and is considered to reflect a biomarker of long-term total phosphate burden.11 In the presence of its co-factor Klotho, FGF-23 reduces gastrointestinal phosphate absorption, promotes renal phosphate excretion, and lowers renal conversion of 25-(OH)-D3 into 1,25-(OH)-D3.12 Circulating levels of FGF-23 have been shown to predict mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease.13-15 Recently, this relationship has also been observed in patients with normal renal function and documented coronary artery disease,16 as well as in the general population.17

Increasing evidence suggests an association between FGF-23 and structural myocardial damage. Three studies showed increased left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with elevated FGF-23 levels.18-20 In over 800 patients undergoing elective coronary angiography with mainly preserved renal function, FGF-23 concentration was associated with atrial fibrillation and left ventricular dysfunction.21 Furthermore, FGF-23 is an independent predictor of survival in patients with stable systolic heart failure.22,23 Data investigating the role of FGF-23 in CS or critically ill patients are lacking. The present study examined the prognostic value of circulating FGF-23 levels in patients with infarction-related CS.

Methods

Patients and study design

Patients with infarction-related cardiogenic shock

In a prospective mono-centric study, FGF-23 was measured in 51 patients with infarction-related CS who had a TIMI-III-flow24 after acute coronary intervention. The study was approved by and performed according to the institutional review board and according to the WHO guidelines for good clinical practice.25,26 Critical illness was defined as a minimum Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) of 30 points.27 Informed written consent was obtained from patient or substitute decision makers. CS was defined as clinical signs of hypoperfusion, such as cool extremities owing to centralization, decreased urine output or alteration in mental status. Clinical diagnosis was confirmed by hemodynamic parameters: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg in the absence of hypovolemia or the need for vasopressors, a reduction of cardiac index (<1.8 l/min/m2) and/or an elevation in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure >18 mmHg.25 Patients resuscitated before admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) were excluded. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed in all patients. The physician in charge decided according to clinical needs whether or not to implant an Intraaortic balloon pump (IABP). The use of inotropes, vasopressors and further concomitant treatments was decided according to judgment of the treating intensive care physician. The primary endpoint of the study was 28-day mortality.

Patients with stable coronary artery disease and patients with uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction

Nine-hundred and forty HOM SWEET HOMe study19 participants with stable CAD undergoing elective coronary angiography, who had been included in a prospective study performed in our hospital, served as a primary control group; subjects were recruited between May 2007 and June 2010. FGF-23 measurements from these stable patients have been reported previously.19 Eighteen patients with uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction defined according to the current guidelines served as a second control group.28,29

Laboratory measurements

Blood samples were collected under standardized conditions immediately after admission to the ICU. The samples were centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 minutes at room temperature. Supernatants were stored in aliquots at −80° C until further use. C-terminal FGF-23 levels were measured from plasma samples by ELISA (Immunotopics, San Clemente, CA, USA; low cut-off value 3 rU/ml, high cut-off value 2000 rU/ml. Samples with FGF-23 >2000 rU/ml were measured after dilution). Plasma levels of creatinine, calcium, phosphate were measured by standard methods. NT-proBNP was assessed by electrochemoluminescence (Cobas 8000, Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Hemodynamic measurements

According to the recommendations and guidelines for treatment of CS, hemodynamic assessment was performed using pulmonary artery catheters.1,30 The following hemodynamic parameters were measured: heart rate (HR), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), cardiac index (CI), mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2), cardiac power index (CPI), and systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

Statistics

Data management and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS statistics version 20.0 and GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Categorical variables are presented as percentage of patients and compared using a χ2 test. Continuous data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean, and compared by Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate. The associations between continuous variables were assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation testing. The cut-off-point with a specificity of 80% was determined by performing Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. A Cox regression survival plot was created with separate lines for patients with FGF-23 < 1180 and ≥ 1180 rU/ml, respectively. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to test whether FGF-23 might represent an independent predictor variable for 28-day-survival.

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared with patients with stable CAD, CS patients had lower systolic and diastolic BP, a higher HR, were more often smokers, had a lower ejection fraction (EF) and higher NT pro-BNP levels. Furthermore, levels of creatinine, phosphate, and calcium differed significantly.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at admission of patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and cardiogenic shock (CS).

| Characteristic | Stable CAD (n=940) |

CS (n=51) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66 ± 0.3 | 68 ± 2.0 | 0.007 |

| Male gender (%) | 728/940 (77.4) | 38/51 (74.5) | 0.367 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 150 ± 0.7 | 90 ± 2.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82 ± 0.4 | 46 ± 1.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 68 ± 0.4 | 101 ± 3.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 382/940 (40.6) | 15/51 (29.4) | 0.072 |

| Nicotine (%) | 130/940 (13.8) | 20/51 (39.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||

| Ejection fraction (EF) (%) | 64 ± 0.6 | 33 ± 2.0 | < 0.0001 |

| NT pro-BNP (pg/ml) | 630 ± 45.6 | 12782 ± 1790.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.3 ± 0.02 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | = 0.001 |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 2.3 ± 0.004 | 2.1 ± 0.03 | < 0.0001 |

Categorical variables are presented as percentage of patients and compared by χ2 test. Continuous data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean, and compared by Mann-Whitney test. p values are shown for stable CAD compared with CS.

Nineteen of the 51 CS patients died within 28 days, which corresponds to a mortality rate of 37%. When comparing major demographic characteristics (Table 2), non-survivors had lower BP and a higher HR compared with survivors. No significant differences existed with regards to the main cardiovascular risk factors. As expected, non-survivors had a lower CPI compared with survivors, and they tended to have lower SvO2 and higher SAPS II score.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients with cardiogenic shock (CS) (n=61) according to the 28-day survival; of the 51 included CS patients, 32 were classified as survivors, 19 as non-survivors.

| Characteristic | Survivors (n=32) |

Non-survivors (n=19) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.4 ± 2.9 | 72.2 ± 2.2 | 0.30 |

| Male gender (%) | 71.9 | 79 | 0.74 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 97 ± 4 | 108 ± 5 | 0.03 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 92 ± 3 | 83 ± 3 | 0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 49 ± 2 | 42 ± 3 | 0.03 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 62.5 | 79 | 0.35 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 31.3 | 26.3 | 0.76 |

| Hypertension (%) | 53.1 | 52.6 | 1.00 |

| Nicotine (%) | 43.8 | 31.6 | 0.56 |

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||

| CPI (W/m2) | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.003 |

| SVO2 (%) | 54.4 ± 2.4 | 50.1 ± 3.3 | 0.24 |

| Ejection fraction (EF) (%) | 33.2 ± 2.5 | 32.2 ± 3.4 | 0.80 |

| SAPS II Score | 36.4 ± 2.9 | 41.7 ± 3.7 | 0.25 |

| Inotropes (%) | 75.0 | 84.2 | 0.50 |

| IABP (%) | 96.9 | 100 | 1.00 |

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 18.8 | 31.6 | 0.33 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| NT pro-BNP (pg/ml) | 11,168.1 ± 2160.6 | 15,250.4 ± 3080.5 | 0.17 |

| CK max (U/l) | 2129.1 ± 556.2 | 4326.2 ± 1593.0 | 0.16 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.30 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 0.09 |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 2.2 ± 0.03 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.05 |

Categorical variables are presented as percentage of patients and compared by χ2 test. Continuous data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean, and compared by Mann-Whitney test.

FGF-23 is increased in cardiogenic shock and related to survival and disease severity

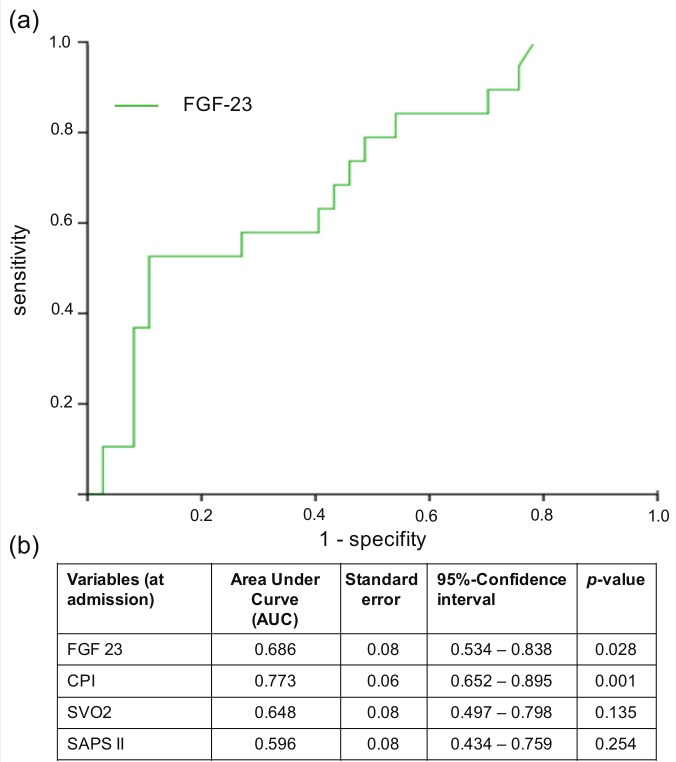

Compared with patients with stable CAD, circulating FGF-23 levels were profoundly elevated in patients with CS (CAD: 131.1±9.5 vs. CS: 1684.4±591.7 rU/ml, p<0.0001). In contrast, FGF-23 levels among patients with uncomplicated AMI (175.3±57.2 rU/ml) did not differ from patients with stable CAD (Figure 1(a)). Within CS patients, non-survivors had significantly higher FGF-23 levels compared with survivors (3260.1±1514.7 vs. 847.9±182.4 rU/ml, p=0.028) (Figure 1(b)). FGF-23 levels correlated with both SAPSII score (r=0.461, p=0.0003) and NT-pro BNP levels (r=0.489, p=0.001) in CS patients (Figure 2(a) and (b)). Furthermore, there was a significant inverse correlation with SvO2 (r= -0.323, p=0.021) as a marker of tissue hypoperfusion. There was no significant correlation with left ventricular EF or with plasma phosphate.

Figure 1.

(a) FGF-23 serum levels in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD), uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and cardiogenic shock (CS). Data are shown as mean±SEM. (b) FGF-23 serum levels in survivors (n=32) and non-survivors (n=19) of cardiogenic shock. Data are shown as mean±SEM.

Figure 2.

Spearman correlations of FGF-23 serum levels with (a) SAPS II Score and (b) NT pro-BNP serum concentrations. To allow better visibility, results from four patients with FGF-23 > 6000 rU/ml are not depicted.

When stratifying CS patients by FGF-23 levels into quartiles, significantly more non-survivors had increased FGF-23 levels above the third quartile compared with survivors (47.4 vs. 9.4%, p=0.003).

FGF-23 is a predictor for survival in patients with cardiogenic shock

As shown in the ROC analysis, FGF-23 levels showed a high diagnostic accuracy in predicting mortality in CS patients. Figure 3 depicts the ROC curve for FGF-23 and the AUC and p-values for different prognostic variables. FGF-23 showed a higher AUC (0.686) compared with the established prognostic markers SAPS II score and SvO2. From these ROC curve data, we arbitrarily selected the FGF-23 concentration which predicted mortality with a specificity of 80% (1180 rU/ml) as the best cut-off value for further analyses.

Figure 3.

(a) Receiver operating curve (ROC) assessing the prognostic accuracy of FGF-23 in predicting 28-day mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock. (b) Areas under the curve (AUC) for FGF-23 compared with other prognostic parameters in cardiogenic shock CPI: cardiac power index; SvO2: mixed venous oxygen saturation, SAPS II score.

As shown in the multivariate Cox regression survival plot in Figure 4, patients with FGF-23 levels above the cut-off level of 1180 rU/ml had a nearly threefold increased rate of death compared with patients with FGF-23 levels below this cut-off level independently of gender, blood pressure at admission, EF and myocardial infarction size measured by creatine kinase (CK); hazard ratio (HR) 2.74, 95% CI 1.01–7.04, p=0.037.

Figure 4.

(a) Multivariate Cox regression survival plot with separate lines for patients with FGF-23 < 1180 rU/ml and ≥ 1180 rU/ml, respectively. (b) Results of the multivariate analysis. SBP: systolic blood pressure; EF: ejection fraction; CKmax: maximum of creatine kinase.

Discussion

The present study reports for the first time a profound increase in plasma FGF-23 in patients presenting with CS. Moreover, patients with highest FGF-23 levels had a worse outcome, and FGF-23 independently predicted short-term mortality.

The clinical implications of these findings may be threefold. Firstly, although further underscoring the idea of a major interplay between high FGF-23 and cardiovascular disease, they challenge our present understanding of its temporal sequences. The presence of such interplay was first reported by epidemiological studies, which associated hyperphosphatonism with adverse outcome.9 Given the tremendous rise in FGF-23 levels in subjects with impaired renal function,31 FGF-23 was reported to predict cardiovascular events13,15 and overall mortality13,14,32 in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Recently, the association between plasma FGF-23 and impaired cardiovascular outcome was expanded towards subjects not pre-selected by prevalent CKD.16,17 Of note, all earlier epidemiological studies13-17 considered FGF-23 a direct or indirect pathophysiological mediator of cardiovascular disease, the latter potentially via inhibiting activation of vitamin D. This idea was further corroborated by cross-sectional data on associations of FGF-23 levels with left-ventricular hypertrophy,18-20 atrial fibrillation and impaired systolic left ventricular function.21 Furthermore, recent epidemiological studies reported FGF-23 to predict mortality in patients with chronic systolic heart failure,22,23 even after adjusting for conventional risk markers including natriuretic peptides. Notably, experimental evidence showed direct harmful effects of FGF-23 on myocardial tissue in vivo and in vitro,18 so that it gradually became accepted as a direct inducer of subsequent cardiac disease.33

Against this background, our finding of increased FGF-23 levels in the acute setting of CS partly challenges the idea that hyperphosphatonism only precedes cardiovascular disease, and it suggests that under certain circumstances, cardiac disease may induce rather than follow hyperphosphatonism. Admittedly we cannot provide patients’ data on FGF-23 and kidney function before the onset of CS, as patients were recruited after hospital admission. Nonetheless, we measured FGF-23 levels that by far surpass those found in stable patients with either impaired left-ventricular systolic function21 or mild to moderate CKD.31 Moreover, all patients suffered from infarction-related CS, and earlier studies failed to associate FGF-23 levels with subsequent myocardial infarction.16,17 These arguments refute the idea that severe hyperphosphatonism preceded CS in our patients. Instead, our findings strongly suggest that CS may induce FGF-23 secretion.

The underlying pathophysiological pathways remain to be elucidated. Hypoxemia might be considered a trigger for excess FGF-23 production.34 This hypothesis is supported by the fact that there was a significant inverse correlation between FGF-23 levels and the SVO2, a marker of tissue hypoperfusion. Alternatively, given acute heart failure is characterized by a strong activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAAS), and that hyperphosphatonism has been linked to an increased activity of the RAAS,35 such an interaction might also contribute to the results. Interestingly, in patients with CS after myocardial infarction, the low cardiac output induced by a severe left ventricular dysfunction rather than acute myocardial ischemia per se appeared to increase FGF-23 secretion, as FGF-23 was only elevated in CS, but not in uncomplicated AMI patients.

It is tempting to speculate that the strong association between FGF-23 and adverse cardiovascular outcome in earlier studies13,15-17 might partly be caused by reverse association, where elevated baseline FGF-23 was reflecting prevalent subclinical cardiac disease, rather than being induced by incident cardiac disease. Notably, large cohort studies found FGF-23 concentrations to predict mortality and future heart failure events rather than acute myocardial infarction.16,17

A second implication of our study is the identification of FGF-23 as a predictor for adverse outcomes in CS. If future larger trials confirm this predictive role of FGF-23, stratification of CS patients by FGF-23 at hospital admission might allow to better identify patients with highest risk for mortality, who may need more aggressive treatment than patients at moderate risk.

As a final implication, our findings might point toward new therapeutic strategies in CS. High FGF-23 levels can be reduced by several pharmacological interventions, of which some have already been introduced into clinical medicine (such as oral phosphate binders), whereas others are still under development (such as direct FGF-23 inhibitors or receptor blockers). Therefore, it will be of considerable interest to learn whether in CS, hyperphosphatonism only represents an innocent bystander, or whether it may exert direct harmful cardiovascular effects.

Our study has some potential limitations. First, the results are only observational. Therefore, they do not prove causality but are hypothesis generating. Second, we used a historical control group of patients included in a previous study conducted between 2007 and 2010. Third, we did not collect urine samples from our study participants; therefore, renal phosphate handling in CS cannot be analyzed in detail. Furthermore, we cannot provide a detailed analysis of renal function in the setting of CS. We did not observe significant differences in plasma creatinine concentrations between survivors and non-survivors. As creatinine is not a valid marker of renal function in acute kidney injury, the latter might have contributed to hyperphosphatonism in our CS patients.

In summary, we report a tremendous acute rise of FGF-23 in patients with infarction-related CS, which challenges our pathophysiological understanding of temporal relationships between hyperphosphatonism and cardiac disease. Moreover, we show that FGF-23 predicts short-term mortality in CS. Future experimental and clinical trials should explore the pathophysiological implications of hyperphosphatonism in CS in order to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest: JP and SS received speaker honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis. GHH received speaker fees and travel grants from SHIRE.

References

- 1. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC Eur J Heart Failure 2012; 14: 803–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, et al. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. New Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1162–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, et al. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A population-based perspective. Circulation 2009; 119: 1211–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kouraki K, Schneider S, Uebis R, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcome of 458 patients with acute myocardial infarction requiring mechanical ventilation. Results of the BEAT registry of the ALKK-study group. Clin Res Cardiol 2011; 100: 235–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: Expanding the paradigm. Circulation 2003; 107: 2998–3002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foley RN. Phosphate Levels and Cardiovascular Disease in the General Population. Clin J Am Soc Nephro 2009; 4: 1136–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tuttle KR, Short RA. Longitudinal Relationships among Coronary Artery Calcification, Serum Phosphorus, and Kidney Function. Clin J Am Soc Nephro 2009; 4: 1968–1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Larsson TE, Olauson H, Hagstrom E, et al. Conjoint effects of serum calcium and phosphate on risk of total, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular mortality in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30: 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tonelli M, Curhan G, Pfeffer M, et al. Relation between alkaline phosphatase, serum phosphate, and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality. Circulation 2009; 120: 1784–1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, et al. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 683–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Larsson TE. The role of FGF-23 in CKD-MBD and cardiovascular disease: friend or foe? Nephrol Dialysis Trans 2010; 25: 1376–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heine GH, Seiler S, Fliser D. FGF-23: the rise of a novel cardiovascular risk marker in CKD. Nephrol Dialysis Trans 2012; 27: 3072–3081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kendrick J, Cheung AK, Kaufman JS, et al. FGF-23 associates with death, cardiovascular events, and initiation of chronic dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 1913–1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 2011; 305: 2432–2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seiler S, Reichart B, Roth D, et al. FGF-23 and future cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease before initiation of dialysis treatment. Nephrol Dialysis Trans 2010; 25: 3983–3989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parker BD, Schurgers LJ, Brandenburg VM, et al. The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: The Heart and Soul Study. Ann Int Med 2010; 152: 640–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ix JH, Katz R, Kestenbaum BR, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and death, heart failure, and cardiovascular events in community-living individuals: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 200–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 4393–4408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gutierrez OM, Januzzi JL, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2009; 119: 2545–2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mirza MA, Larsson A, Melhus H, et al. Serum intact FGF23 associate with left ventricular mass, hypertrophy and geometry in an elderly population. Atherosclerosis 2009; 207: 546–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seiler S, Cremers B, Rebling NM, et al. The phosphatonin fibroblast growth factor 23 links calcium-phosphate metabolism with left-ventricular dysfunction and atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 2688–2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gruson D, Lepoutre T, Ketelslegers JM, et al. C-terminal FGF23 is a strong predictor of survival in systolic heart failure. Peptides 2012; 37: 258–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Plischke M, Neuhold S, Adlbrecht C, et al. Inorganic phosphate and FGF-23 predict outcome in stable systolic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 2012; 42: 649–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. TIMI Study Group. New Engl J Med 1985; 312: 932–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. New Engl J Med 1999; 341: 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Idanpaan-Heikkila JE. WHO guidelines for good clinical practice (GCP) for trials on pharmaceutical products: responsibilities of the investigator. Ann Med 1994; 26: 89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 1993; 270: 2957–2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2551–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Link A, Pöss J, Rbah R, et al. Circulating angiopoietins and cardiovascular mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J 2013. January 24 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Werdan K, Russ M, Buerke M, et al. Cardiogenic shock due to myocardial infarction: diagnosis, monitoring and treatment: a German-Austrian S3 Guideline. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int 2012; 109: 343–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seiler S, Wen M, Roth HJ, et al. Plasma Klotho is not related to kidney function and does not predict adverse outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2013; 83: 121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. New Engl J Med 2008; 359: 584–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heine GH, Nangaku M, Fliser D. Calcium and phosphate impact cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 1112–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhattacharyya N, Chong WH, Gafni RI, Collins MT. Fibroblast growth factor 23: State of the field and future directions. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012; 23: 610–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Borst MH, Vervloet MG, ter Wee PM, Navis G. Cross talk between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and vitamin D-FGF-23-klotho in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 1603–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]