Abstract

Cell cycle quiescence is a critical feature contributing to haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance. Although various candidate stromal cells have been identified as potential HSC niches, the spatial localization of quiescent HSCs in the bone marrow (BM) remains unclear. Here, using a novel approach that combines whole-mount confocal immunofluorescence imaging techniques and computational modelling to analyse significant tridimensional associations among vascular structures, stromal cells and HSCs, we show that quiescent HSCs associate specifically with small arterioles that are preferentially found in endosteal BM. These arterioles are ensheathed exclusively by rare NG2+ pericytes, distinct from sinusoid-associated LepR+ cells. Pharmacological or genetic activation of HSC cell cycle alters the distribution of HSCs from NG2+ peri-arteriolar niches to LepR+ peri-sinusoidal niches. Conditional depletion of NG2+ cells induces HSC cycling and reduces functional long-term repopulating HSCs in BM. These results thus indicate that arteriolar niches are indispensable to maintain HSC quiescence.

Somatic stem cells self-renew to maintain tissue homeostasis for the lifetime of organisms through tightly controlled proliferation and differentiation1–3. In the bone marrow (BM), recent studies have highlighted the critical influence of the microenvironment in regulating haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance4. Deletion `of genes involved in maintaining cell cycle quiescence has taught that unchecked HSC proliferation often leads to stem cell exhaustion5–8. While most HSCs are quiescent under homeostasis9, they can undergo activation for example by interferon-mediated signals7,10,11. This raises the question of whether quiescent and proliferative HSCs are found in the same niche.

The identification of cellular constituents of the HSC niche has recently been the subject of intense studies. Initial reports have suggested that osteoblasts are niche cells as HSCs tend to localize near endosteal surfaces12 and that factors increasing osteoblast numbers can also increase the number of HSCs12,13. N-cadherin+ osteoblasts have been proposed to promote HSC quiescence via direct contact12,14 and secretion of angiopoietin-115 or osteopontin16,17. However, the synthesis of these factors is not specific to osteoblasts and other studies have found that most BM HSCs are found near sinusoidal endothelial cells18, and perivascular stromal cells including, CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells19,20, Nestin+ mesenchymal stem cells21 or Leptin receptor (LepR)+ cells22. Based on these data, a prevalent unifying interpretation of the literature has been that the osteoblastic and vascular niches confer distinct microenvironments promoting quiescence and proliferation, respectively2,23. However, this popular concept has not been supported by rigorous analyses. To evaluate this issue, we have used novel tridimensional (3D) BM imaging combined with computational modelling to assess significant relationships between endogenous quiescent HSCs and stromal structures. These studies have allowed us to identify distinct vascular niches mediating stem cell quiescence and proliferation.

HSCs significantly associate with bone marrow arterioles

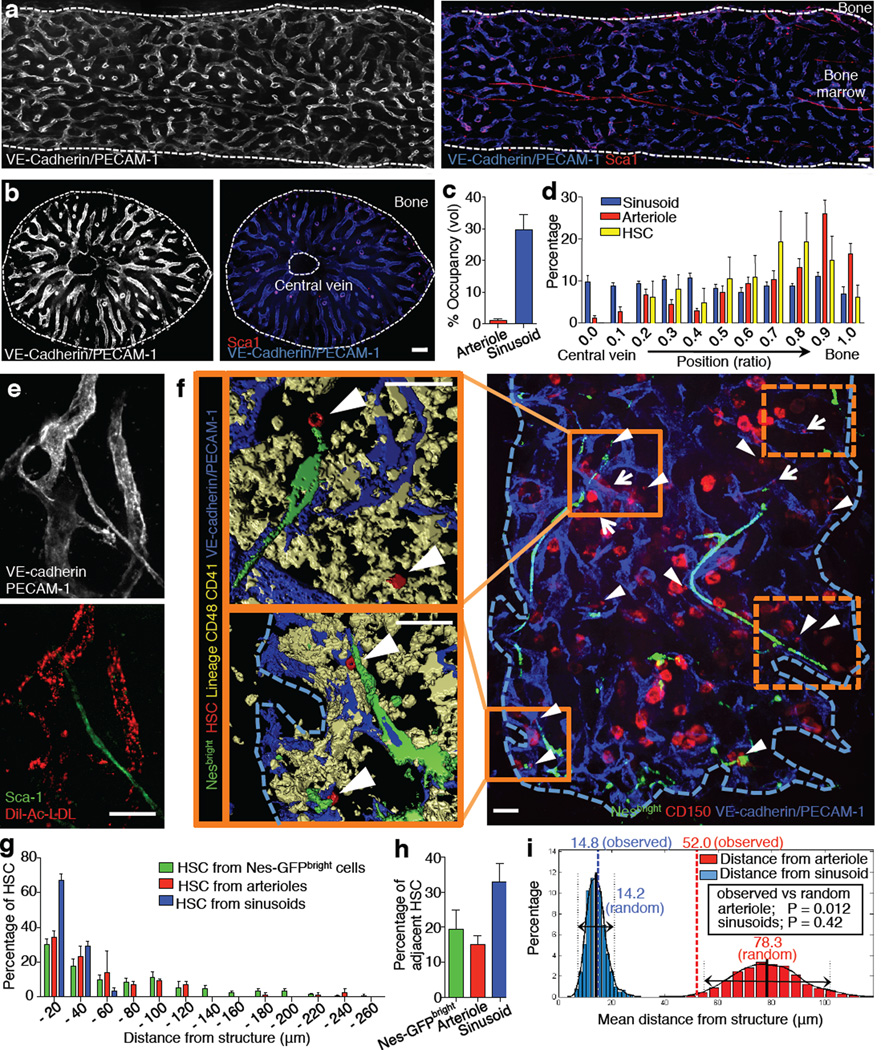

To gain detailed insight into the 3D structure of the HSC niche, we prepared whole-mount tissues to visualise by confocal immunofluorescence imaging the architecture of long-bone and sternal marrow over ~75µm thickness (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). To specifically label BM endothelial cells, we performed in vivo staining (Extended Data Fig. 1c–e). Whole-mount assessment of the femoral BM vasculature revealed an even distribution of the sinusoidal network that occupies 30±5% of the BM volume (Fig. 1c,d) and where individual sinusoidal vessels are regularly spaced by 46±1µm (Extended Data Fig. 1f). In addition to the sinusoidal network, 3D visualisation of the BM vasculature highlighted the presence of small calibre (10–20µm) Sca-1hi VEGFR2+ VEGFR3− arterioles24, which were found predominantly in close proximity to the bone25 and comprised a much smaller volumetric fraction 1.2 ± 0.1% of the BM (Fig. 1a–d and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). The vessels were confirmed as bona fide arterioles by their pronounced Tie-2-GFP expression26, absence of in vivo staining with the sinusoid-specific Dil-Ac-LDL26, and strong staining with the artery-specific dye Alexa Fluor633 (ref.27) (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2b–f). The distribution of phenotypic CD150+ CD48− CD41− Lineage− HSCs18 was not uniform as they localized predominantly to the peripheral zone rather than in close proximity to the central vein in the long-bone BM (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3a). We validated the identification of rare phenotypic HSCs by using whole-mount preparations of the mouse sternum28. Unlike long bones which are mostly occupied by adipocytes in adult humans29, the sternum exhibits rich hematopoietic activity in both species. The mouse sternum is made of six thin bone compartments in which all HSCs can be enumerated (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 3b,c).

Figure 1. Spatial relationships between HSCs and the bone marrow vasculature.

a,b, Longitudinally (a) and transverse-shaved (b) whole-mount images of the mouse femoral BM stained with anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin and anti-Sca-1 antibodies. Scale bar: 100 µm. c, BM volumes occupied by arterioles or sinusoids. n = 6 areas from 3 mice. d, Distribution of sinusoids, arterioles and HSCs in the femoral BM. n = 6 mice. e, Whole-mount images of sternum stained with anti-VE-cadherin, anti-PECAM-1, anti-Sca-1 antibodies and Dil-Ac-LDL. Scale bar: 50 µm. f, Illustrative example of whole-mount sternal BM with 3D reconstructed images. Dashed squares are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3b. Arrowheads denote HSCs, arrows show CD150+ Lin/CD48/CD41+ cells. Scale bar: 50 µm. g,h, Distances between HSCs and Nes-GFPbright cells (n = 98 HSCs from 5 mice), arterioles or sinusoids (n = 119 HSCs from 5 mice) (g) and percentages of adjacent HSCs (distance = 0) (h) in the sternal BM. i, Probability distributions of mean distances from simulations of randomly positioned HSCs on maps of sternal BM in relation to sinusoids (blue) or arterioles (red). Mean distances observed in situ (dashed) are shown in relation to the grand mean ± 2 s.d. (solid and dotted lines).

The absolute numbers of HSCs per sternal bone compartment, determined by whole-mount imaging, was similar to assessment by FACS, indicating that the staining of endogenous HSCs was reliable (Extended Data Fig. 3d). We next examined the spatial relationships between individual HSC and arterioles and sinusoids, by whole-mount immunostaining of sternal BM. We found that 36.8±1.8% and 67.1±3.5% of HSCs were located within 20µm distance from arterioles and sinusoids, and 14.9±2.5% and 32.9±5.2% were adjacent to those vessels, respectively (Fig. 1g,h and Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). The high proportion of HSCs near sinusoids is consistent with previous reports18,19.

Since the BM sinusoidal network was dense and appeared to be regularly interspaced, we evaluated in more detail whether the spatial distribution of HSCs was independent of the sinusoidal network or significantly biased in relation to a putative sinusoidal niche. To address this issue, we developed a computational simulation to assess the statistical relevance of these associations (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). We carried out 1,000 simulations in which 20 HSCs were randomly positioned on images of whole-mount prepared sterna. We found that the mean distance observed in situ to sinusoids could not be statistically differentiated from that of randomly placed HSCs (14.2µm and 14.8µm for random and observed; Fig. 1i). By contrast, the observed mean distance to arterioles (52.0µm) was highly statistically different from that of randomly placed HSCs (78.3µm, P = 0.012; Fig. 1i). Thus, these data suggest that associations between HSCs and arterioles are highly significant whereas the close relationship observed with sinusoids could not be discriminated from that of a random distribution.

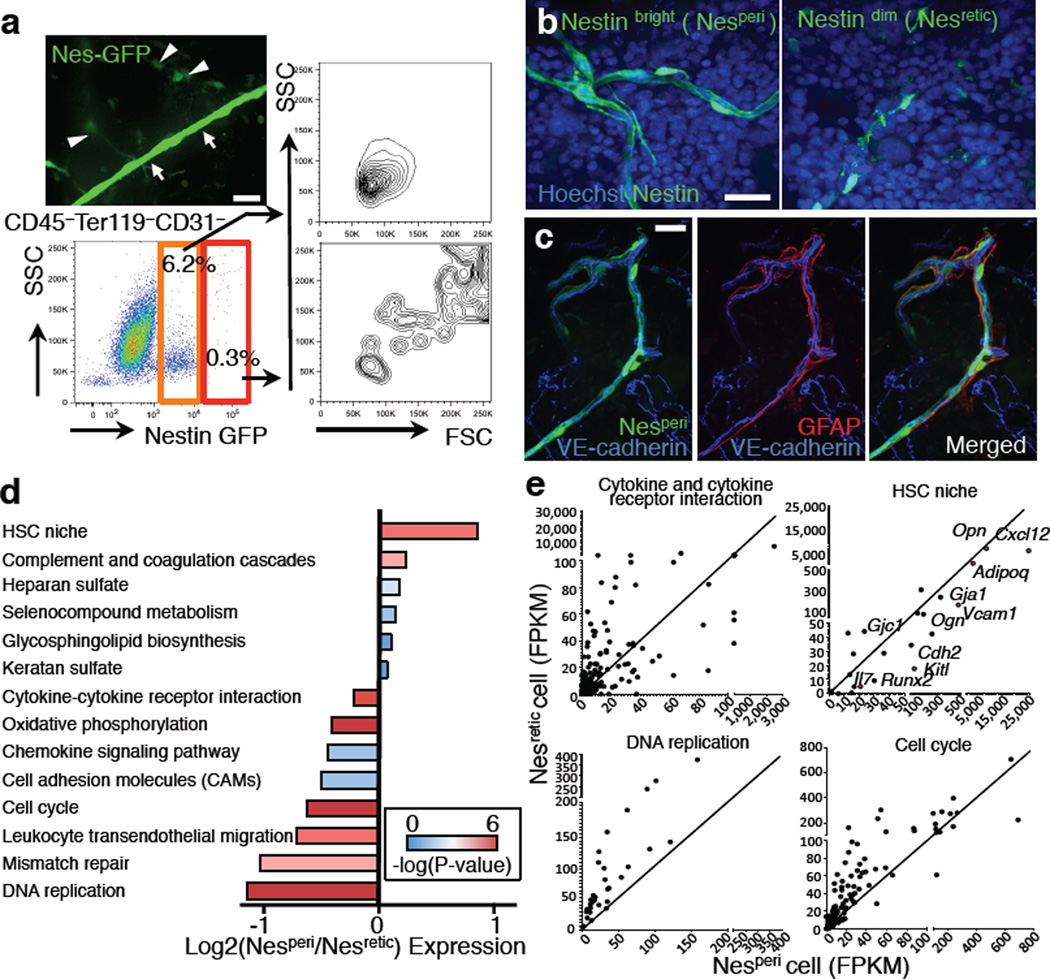

Distinct Nestin+ cells segregate with distinct blood vessels

Nestin+ perivascular cells have been identified as HSC niche cells containing all BM mesenchymal stem cell activity21. Detailed 3D imaging and FACS analyses revealed two distinct types of Nes-GFP+ cells in the BM based on their GFP expression levels and cellular morphology (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Nes-GFPbright cells were much rarer (~0.002% of BM) than Nes-GFPdim cells (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 5b), and found exclusively along arterioles in both sternal and long-bone BM (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e, 5c–h). Consistent with this observation, similar HSC distribution patterns were obtained when plotting distances from arterioles or from Nes-GFPbright cells (hereafter referred to as peri-arteriolar Nestin cells, Nesperi; Fig. 1g,h and Extended Data Fig. 3e,f, P = 0.97). The more abundant Nestin-GFPdim population was reticular in shape (hereafter referred to as Nesretic cells) and was largely associated with sinusoids (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3e,f, 5g). Nesperi cells, but not Nesretic cells, were decorated with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)+ sympathetic nerves and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)+ Schwann cells which were reported to modulate HSC behaviour in the BM30–32 (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 5i). While both Nestin+ cell subsets accounted for the mesenchymal progenitor activity (CFU-F) in BM, most CFU-F were contained in Nesperi cells (Extended Data Fig. 5j). To get additional insight into potential differences between these two stromal subsets, we subjected Nesperi and Nesretic cells to RNA-seq analyses. Comparison of the whole genome transcriptome revealed differential enrichment of several molecular pathways and functional clusters, including HSC niche, cytokine/receptor interactions, DNA replication and cell cycle (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Table 1). Indeed, Nesperi cells showed significantly higher expression of genes associated with the HSC niche (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 5k). In addition, expression of genes in two pathways, DNA replication and cell cycle, was significantly enriched in Nesretic cells (Fig. 2d,e), suggesting that the two subsets had differing cell cycle characteristics.

Figure 2. Nestin+ cell subsets define distinct vascular structure.

a, A whole-mount image of sternal BM with Nes-GFPbright (arrows) and Nes-GFPdim cells (arrowheads) and FACS analysis of BM stromal cells from Nes-GFP mice. Data were reproducible in at least 5 mice. b,c, Whole-mount images of sternum from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-GFP and Hoechst 33342 (b) or anti-GFAP antibody (c). d,e, RNA-seq analysis of Nesretic and Nesperi cells. d, Differentially expressed pathways. Mean of log fold change of Nesperi/Nesretic expression was plotted for each pathway with colour-coded P-values. e, Dot plots showing gene expression levels in FPKM for representative pathways and functional groups.

Arteriolar Nesperi niche cells are quiescent and protected from myeloablation

Based on these results, we evaluated in more detail the cell cycle status of BM stromal cells, and more specifically of Nesretic and Nesperi cells. Expression of the nuclear proliferation markers, Ki-67 and proliferation cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), in Nesperi cells was significantly lower than in Nesretic cells and CD45− Ter119− CD31− Nes-GFP− stromal cells (Fig. 3a,b), which was confirmed by FACS analysis (Fig. 3c,d). To test the relevance of niche cell quiescence, we challenged mice with 5-fluorouracil (5FU), a drug that kills cycling cells. After 5FU administration, Nesperi cells were largely preserved structurally and numerically compared to Nesretic cells (Fig. 3e–g), confirming their quiescent state.

Figure 3. Quiescent arteriolar niche cells are protected from myeloablation.

a, Whole-mount immunostaining with anti-Ki-67 antibody of sterna from Nes-GFP mice. Scale bar: 50 µm. b, Q-PCR analyses of Nesperi, Nesretic and CD45− Ter119− CD31− Nes-GFP− stromal cells. n = 5 independent experiments. c,d, Cell cycle analyses by FACS using anti-Ki-67 and Hoechst 33342 staining. Representative plots (c) and quantification (d). n = 3 mice per group. e–g, Whole mount images of sternal BM (e) and the kinetics of absolute numbers (f) and frequencies (g) of Nesperi and Nesretic cells in the long-bone BM analysed by FACS after 5FU treatment. n = 10, 9, 9, 5, 6 mice per time point. Scale bar: 100 µm.

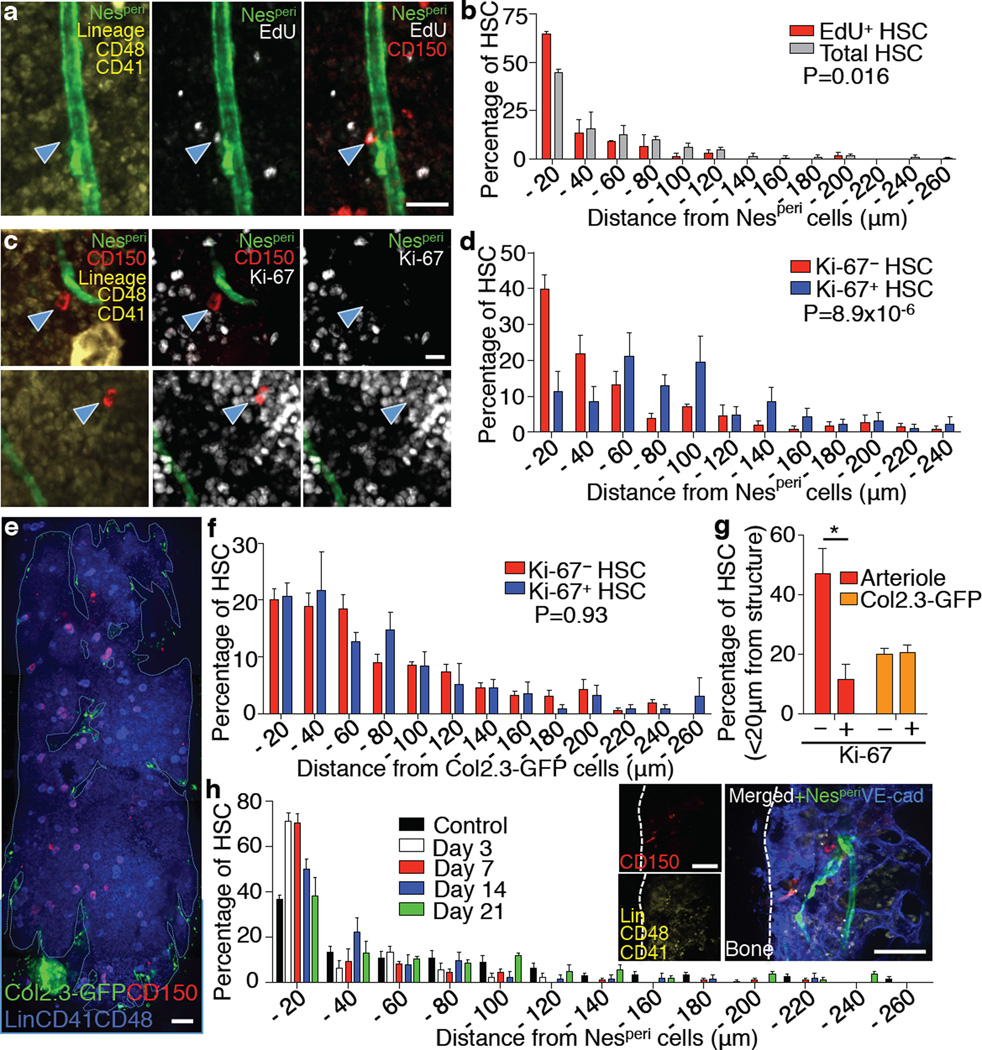

HSC quiescence is associated with localization in vascular niches

We hypothesized that the arteriolar quiescent niche cells may themselves harbour quiescent HSCs. Consistent with previous studies10,33, we found that most HSCs were not actively cycling, but ~20% of HSCs were in the non-quiescent G1 phase of the cell cycle (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Prolonged quiescence has been referred to as dormancy and tracked as label-retaining cells (LRCs)10. We first evaluated the spatial associations of dormant HSCs with Nesperi cells by LRC pulse-chase experiments with EdU in the long-bone BM. Significantly more EdU+ CD150+ CD48− CD41− Lineage− HSCs compared to total HSCs were located within 20µm distance from Nesperi cells (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Fig. 6b; 65.8±0.8% vs 44.3±1.8%, P = 0.016). We next analysed the cell cycle status and distribution of HSCs in relation to arterioles with Ki-67 staining in the sternal BM and found that a significantly higher proportion of Ki-67− quiescent HSCs were located within 20µm distance compared to Ki-67+ non-quiescent HSCs (Fig. 4c,d,g and Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). There was no significant difference in the proportions of adjacent cells between quiescent and non-quiescent HSCs (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c), suggesting that proximity to arterioles, rather than direct contact, promotes HSC quiescence. Since osteoblasts have been suggested to be associated with quiescent HSCs12,14–17, we evaluated the distribution of HSCs in relation to osteoblasts in the sternal BM using transgenic mice expressing GFP under a 2.3kb fragment of the collagen promoter (Col2.3-GFP), in which osteoblasts and osteocytes express GFP34. We found that 20.7±1.9% of total HSCs were located within 20µm distance from Col2.3-GFP+ cells (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 6e). We performed the computational simulation with Col2.3-GFP+ cells and found that in contrast to arterioles, HSCs were not significantly associated with Col2.3-GFP+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the distribution of quiescent and non-quiescent HSCs in relation to Col2.3-GFP+ cells in the sternal BM (Fig. 4f,g and Extended Data Fig. 6g, P = 0.93). These results suggest that quiescent HSCs are preferentially associated with arterioles in both long-bone and sternal marrow.

Figure 4. Spatial relationship between arterioles and quiescent HSCs.

a,b, Localization of dormant HSCs accessed by long-term label retention with EdU. Representative images (a) and distribution of total and EdU+ CD150+ CD48− CD41− Lineage− HSCs in femoral BM sections (b). n = 144, 52 HSCs from 3 mice. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.016. Scale bar: 25 µm. c,d, Localization of Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs in the sternal BM. Ki-67− / Ki-67+: 39.7±3.9% / 11.4±5.6% in 0–20µm proximity, 21.5±5.3% / 47.9±6.5% > 80µm distance. Representative images (c) and distances from Nesperi cells (d). n = 116, 64 HSCs from 7 mice. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 8.9×10−6. Scale bar: 10 µm. e–g, Localization of HSCs in relation to osteoblasts. e, Whole-mount images of sternum from Col2.3-GFP mice with HSC staining. Scale bar: 100 µm. f, Distances of Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs from Col2.3-GFP cells. n = 80, 41 HSCs from 3 mice. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.93. g, Percentage of Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs located within 20µm distance from arterioles or Col2.3-GFP cells. n = 7, 3 mice per group. h, Localization of HSCs relative to Nesperi cells after 5FU treatment. Inset shows a representative image of sternal BM on day 7. n = 98, 39, 70, 55, 112 HSCs from 5, 9, 7, 4, 4 mice per group. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Day 3 P =2.8×10−4, Day 7 P =1.0×10−4, Day 14 P =0.0013, Day 21 P =0.23 compared to control. Scale bar: 50 µm.

To test this idea using functional assays, we evaluated HSC-arteriole associations in mice treated with 5FU. We found that at nadir, on days 3 and 7, the vast majority of HSCs was closely associated with Nesperi cells (Control/Day 3/Day 7; 34.4±1.0/71.1±3.9/70.6±4.0% in 0–20µm) and that HSCs expanded in further distance from Nesperi cells upon recovery in the sternal BM (Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 6h,i). These data indicate that arterioles indeed provide a milieu promoting quiescence for both HSCs and their niche cells, and a safe harbour to protect them against genotoxic insults.

We next tested whether changes in HSC cycling would lead to altered distribution. To this end, we injected mice with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)), a compound reported to induce proliferation of HSCs via interferon-α (IFN–α) production, which can lead to HSC exhaustion7,8. Poly(I:C) treatment increased the fraction of non-quiescent HSCs (Extended Data Fig. 7a) and altered their distribution in relation to arterioles in that the percentage of HSCs within 20µm was significantly reduced compared to PBS-treated animals in the sternal BM (Extended Data Fig. 7b, P = 0.007). Furthermore, we evaluated a genetic mouse model deficient in promyelocytic leukaemia protein (Pml−/−) that was shown to compromise HSC quiescence in a cell-autonomous manner and caused HSC exhaustion6. Remarkably, endogenous HSCs were distributed significantly further away from arterioles in Pml−/− mice compared to wild type (WT) animals (Extended Data Fig. 7c, P=1.9×10−6). Notably, the location of quiescent Ki-67− cells was dramatically affected (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e). These data suggest the possibility that there are spatially distinct niches for quiescent and proliferating HSCs in the BM.

To further confirm this notion, we treated mice with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), a drug commonly used to mobilise HSCs from the BM to the circulation, and that is also known to induce HSC proliferation35,36. Short-term (1 or 2 days) administration of G-CSF led to altered HSC distribution further away from Nesperi cells. By contrast, further treatment (4 days) led to expansion of HSCs around Nesperi cells (Extended Data Fig. 7f,g). In line with these data, G-CSF also down-regulated HSC retention factors such as CXCL12 in the Nestin+ niche cells21, which also may contribute to the shift from the quiescent to the proliferative (mobilisable) niches at early phase, the release of the mobilisable pool, and HSC replenishment at late phase. This model further highlights the importance of local cues in fine-tuning HSC behaviour in the BM.

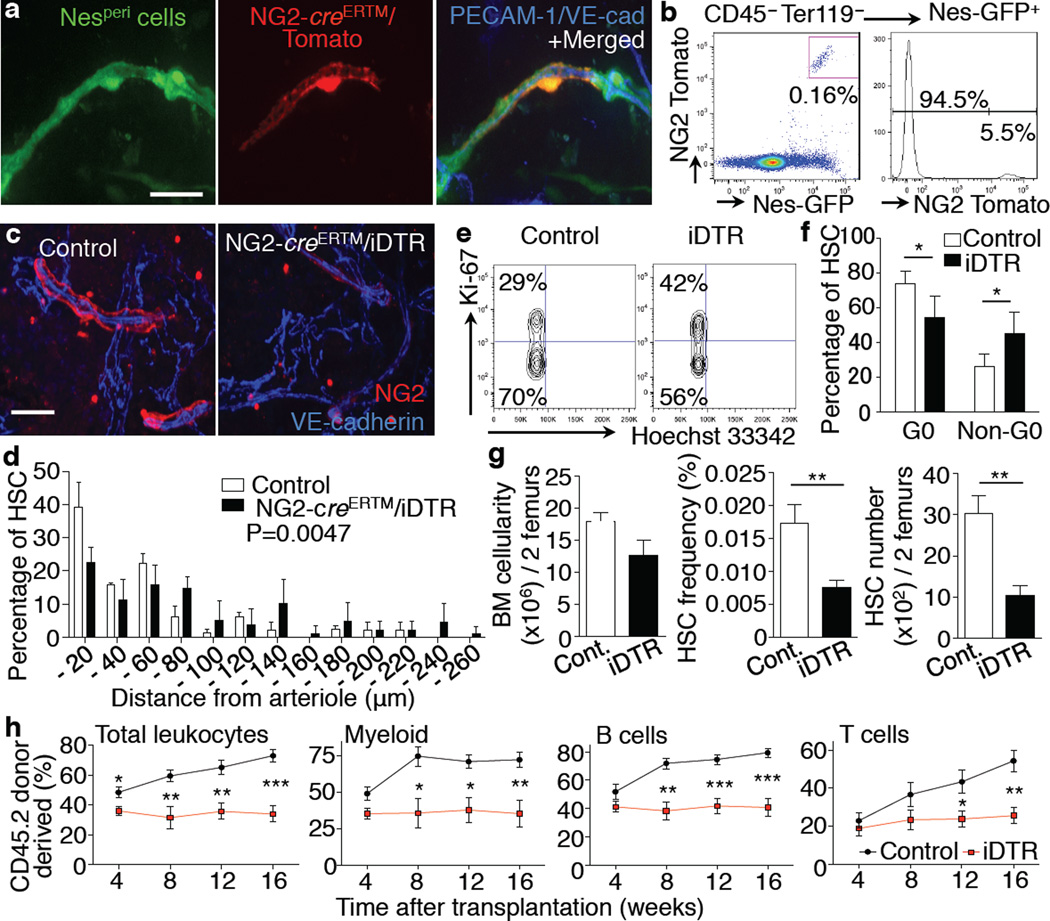

NG2+ Nes-GFPbright periarteriolar niche cells promote HSC quiescence

LepR+ perivascular cells have been reported to represent an important source of stem cell factor (SCF) required for the maintenance of HSCs in the BM22. Since Nestin+ cells were shown to express large amounts of Scf21, we evaluated the overlap between Nesperi or Nesretic cells and LepR+ cells. Using triple-transgenic Lepr-cre/loxp-Tomato/Nes-GFP mice, we found that LepR+ cells were adjacent to sinusoids in a manner similar to Nesretic cells (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Indeed, Nesretic cells largely overlapped (~80%) with LepR+ cells whereas we found no overlap between Nesperi and LepR+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). By contrast, Nesperi cells, but not Nesretic, were positive for the classical pericyte marker NG2 (chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan-4, Cspg4) and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA)37 (Extended Data Fig. 9a–f). To examine further the expression of NG2 on Nesperi cells, we generated triple-transgenic mice to label both NG2+ and Nestin+ cells (NG2-creERTM/loxp-Tomato/Nes-GFP mice). In these mice, 30% of Nesperi cells were labelled by the NG2-creERTM transgene (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 9g,h), a recombination efficiency consistent with that reported for oligodendrocyte progenitors in the brain38. Notably, no labelling was observed in Nesretic cells or in other stromal cells (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 9i).

Figure 5. NG2+ periarteriolar cells are an essential constituent of the HSC niche promoting HSC quiescence.

a,b, Whole-mount images of sternal BM (a) and FACS analysis of femoral BM (b) from NG2-creERTM / loxp-Tomato / Nes-GFP Tg mice. Representative data of 4 mice. c–h, Analysis of HSCs after specific deletion of NG2+ cells using NG2-creERTM/iDTR mice. c, Whole-mount immunostaining of sternum with anti-NG2 antibody. Representative images of 5 mice per group. d, HSC localization relative to arterioles in the sternal BM. n = 69, 71 HSCs from 3, 4 mice per group. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.0047. e,f, Cell cycle analysis of HSCs using Ki-67 and Hoechst 33342 staining. Representative plots (CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− gated) (e) and quantifications (f). n = 5 mice per group. g, BM cellularity, frequency and number of HSCs in the BM. n = 6 mice per group. h, Quantification of long-term reconstituting HSCs by competitive reconstitution assays. n = 6, 9 mice per group. Scale bar: 25 µm.

To examine the function of NG2+ Nesperi cells in HSC maintenance, we intercrossed NG2-creERTM with an inducible diphtheria toxin receptor (iDTR) line. Tamoxifen and diphtheria toxin (DT) treatment depleted ~55% of Nesperi cells without significantly affecting the vascular volume as determined by whole-mount imaging 7–16 days after DT administration (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 10a–c). NG2+ cell depletion also did not affect the expression of HSC niche genes in endothelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 10d,e). However, depletion of NG2+ cells altered HSC localization away from arterioles (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 10f) and switched them into non-quiescent status (Fig. 5e,f). In addition, we found that the number and frequency of HSCs in the BM and spleen, as determined phenotypically (Fig. 5g and Extended Data Fig. 10g) and functionally using long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC; Extended Data Fig. 10h,i) or competitive reconstitution assays (Fig. 5h), were significantly reduced 16 days after DT administration. These results indicate that depletion of NG2+ cells reduces the HSC pool rather than inducing mobilisation to extramedullary sites (Extended Data Fig. 10j). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that rare NG2+ periarteriolar cells promote HSC quiescence and are essential for HSC maintenance in the BM.

Discussion

Here, we show that arterioles organise a critical niche that maintains HSC quiescence in the BM. Arterioles are associated with both quiescent NG2+ niche cells and HSCs, suggesting that the vessel itself may be a critical gatekeeper of stem cell quiescence in the BM. Arterioles are structurally distinct from sinusoids as they are surrounded by sympathetic nerves, layers of smooth muscle cells and matrix components to carry blood from the heart under high pressure (Supplementary Table 2). These differing characteristics translate into significant differences in the transcriptional program of arteriolar and venular endothelial cells39. Likewise, arteriolar Nesperi cells and sinusoidal Nesretic cells can be distinguished by their individual transcriptional profiles reflecting relative enrichments in cell cycle quiescence and HSC niche-related genes in Nesperi cells. The present data show that upon severe genotoxic insult, the mitotically active Nesretic sinusoidal niche cells are largely destroyed, whereas that quiescent Nesperi arteriolar niche cells are chemoresistant. The association and quiescence of both haematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells at this site may thus endow arterioles with the potential for orchestrating haematopoietic and stromal regeneration40.

Given the recent studies showing that CXCL12 derived from mesenchymal progenitors marked by Prx1-cre contributes to HSC maintenance41,42, it is possible that NG2+ Nesperi cells are also targeted by Prx1-cre. Although Nestin-GFP+ cells express high levels of Scf21, Nes-cre mediated deletion of Scf has no effect on HSC function22. This may be due to the low recombination efficiencies among Nestin-GFP+ cells in this model, allowing for compensation by the non-targeted cells. In keeping with the notion that multiple niche constituents exert distinct functions, conditional deletion of Cxcl12 by Lepr-cre does not affect HSC number in the BM, but induces their mobilization42.

The idea that sinusoids may represent a proliferative niche is consistent with recent studies indicating that E-selectin, an adhesion molecule constitutively expressed in certain BM sinusoid microdomains43, promotes HSC proliferation and blockade of E-selectin protects HSCs following chemotherapy or γ-irradiation44. It is therefore conceivable that a continuous exchange between the sinusoidal and arterial niches contributes to maintain a tightly controlled balance of HSC pool between proliferation and dormancy.

An arteriolar niche maintaining stem cell dormancy has the potential to protect haematopoietic malignancies and metastatic cancer stem cells. Gaining knowledge on the reciprocal regulation and functional correlation of these niches will thus have important implications in understanding stem cell fate in health and cancer.

Methods (online-only)

Animals

B6.Cg-Tg(Cspg4-cre/Esr1*)BAkik/J, STOCK Tg (TIE2GFP) 287Sato/J (Tie2-GFP) mice, C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26 Sortm1(HBEGF) Awai/J, B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, B6.129-Leprtm2(cre)Rck/J (Lepr-Cre) (all from Jackson laboratory), C57BL/6-CD45.1/2 congenic strains (from the National Cancer Institute), Pml−/− mice (gift from P.P. Pandolfi) and Nes-GFP mice45 were bred in our facilities. Col2.3-GFP mice were a gift from D.W. Rowe. All mice were maintained on the C57Bl6/J background. Unless indicated otherwise, 7–12 week-old male and female mice were used. No randomization or blinding was used to allocate experimental groups. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Immunofluorescence imaging

In vivo staining of BM endothelial cells

To stain specifically endothelial cells, fluorescently conjugated antibodies (2 µg/mouse), AlexaFluor633(50 µg/mouse) or Dil-Ac-LDL (1 µg/g) were i.v. injected. Mice were perfused with PBS, 10 min (for antibodies) or 4 hours (for AlexaFluor633 and Dil-Ac-LDL) after injection to remove unbound reagents. Sterna and long bones were harvested for FACS or immunofluorescence imaging.

Preparations of whole-mount tissues and frozen sections of long bones

Femoral or tibial bones were perfusion-fixed and then post-fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), incubated in 15% and 30% sucrose for cryoprotection and embedded in OCT at −20°C. For whole-mount staining, bones were shaved on a cryostat until the BM cavity was fully exposed. Bones were carefully harvested from melting OCT. Frozen sections were prepared according to the Kawamoto method46.

Whole-mount tissue preparation of the sternum

Sternal bones were harvested, transected with a surgical blade into 2–3 fragments. The fragments were bisected sagittally for the bone marrow cavity to be exposed, fixed in 4% PFA.

Immunofluorescence staining of whole-mount tissues and frozen sections of the sterna and long bones

Whole-mount tissues and sections were blocked / permeabilized in PBS containing 20% normal goat serum and 0.5% Triton X-100, and stained with primary antibodies for 1–3 days. The tissues were incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 hours. Images were acquired using a ZEISS AXIO examiner D1 microscope (Zeiss) with a confocal scanner unit, CSUX1CU (Yokogawa) and reconstructed in 3-D with Slide Book software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) or Volocity software (PerkinElmer).

High-speed multichannel fluorescence intravital microscopy (MFIM)

We performed MFIM of the calvarial BM as previously described47. BM sinusoids and arterioles were visualized by administration of 10 µg of Rhodamine6G (R6G) and 50 µg of Alexa Fluor633, respectively.

Cell sorting and flow cytometry

For sorting of Nesperi and Nesretic cells, BM cells from 3–5 mice were pooled for a single experiment. BM cells were flushed and digested with 1mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma) and 2mg/ml dispase (Gibco) in HBSS (Gibco) for 45 min at 37°C. All cell sorting experiments were performed using an Aria Cell Sorter (BD). Flow cytometric analyses were carried out using an LSRII flow cytometer equipped with FACS Diva 6.1 software (all BD). Dead cells and debris were excluded by FSC, SSC and DAPI (4',6-diamino-2-phenylindole) (Sigma) staining profiles. Data were analysed with FlowJo (Tree Star) or FACS Diva 6.1 software.

Antibodies and staining reagents

APC-anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), PE-anti-CD11b (M1/70), biotin-anti-Lineage (TER-119, RB6-8C5, RA3-6B2, M1/70, 145-2C11), FITC/PE-anti-CD45.2 (104), PE/PE-Cy7-anti-Ly6A/E (D7), PE/PE-Cy7-anti-CD117 (2B8), biotin-anti-CD48 (HM48-1), biotin-anti-CD41 (MWReg30), FITC/PE/Alexa647-anti-Ki67 (SolA 15), biotin-anti-VEGFR3 (AFL4) (all from eBioscience), Alexa647-anti-VE-cadherin (BV13) APC-anti-CD31 (MEC13.3), FITC/PE/PE-Cy7-anti-CD45.1 (A20), PE-anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2) (all from Biolegend), PE-anti-Flk1 (Avas 12alpha1) (from BD Biosciences), anti-tyrosine hydroxylase and anti-NG2 (all from Millipore), anti-GFAP (DAKO), rabbit anti-GFP, AlexaFluor488/568-anti-rabbit, AlexaFluor633 hydrazide and Dil-labelled acethylated low-density lipoprotein (Dil-Ac-LDL) (all from Invitrogen), Cy3-anti-αSMA antibody, Hoechst 33342, Rhodamine6G (R6G) (all from Sigma), were used in this study.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR)

BM cells were harvested from Nes-GFP mice and Nesperi and Nesretic cells were sorted according to their specific flow cytometric profiles. mRNA was purified with polyT conjugated Dynabeads (Invitrogen) and conventional reverse transcription, using the Sprint PowerScript reverse transcriptase (Clontech), was performed in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Q-PCR was performed with SYBR Green (Roche) on an ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). A primer concentration of 300 nM was found to be optimal in all cases. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used are included in Supplementary Table 3. The PCR protocol consisted of one cycle at 95 °C (10 min) followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C (15 s) and 60 °C (1 min). Expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) was used as standards. The average threshold cycle number (Ct) for each tested mRNA was used to quantify the relative expression of each gene; 2 − [Ct(gene) − Ct(standard)].

RNA preparation and next-generation sequencing

Total RNA from sorted Nesperi and Nesretic cells was extracted using the RNAqueous kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY USA) and concentrated using RNA Clean and Concentrator columns (Zymo Research Corporation, Irvine, CA USA). The integrity and purity of total RNA were assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer and OD260/280. cDNA was generated using a Clontech SMARTer Ultra Low RNA kit for Illumina Sequencing (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA USA) from 100pg–1ng of total RNA. cDNA was fragmented using Covaris (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA USA), profiled using an Agilent Bioanalyzer, and subjected to Illumina library preparation using NEBNext reagents (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA USA, catalog# E6040). The quality and quantity and the size distribution of the Illumina libraries were determined by an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. The libraries were then submitted for Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencing according to the standard operation procedure. Paired-end 90 or 100 nucleotide (nt) reads were generated and checked for data quality using FASTQC (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK) and subjected to data analysis using the platform provided by DNAnexus (DNAnexus, Inc, Mountain View, CA USA). For sorting of Nesperi and Nesretic cells, BM cells from 5–7 mice were pooled to get a single biological sample. Triplicate biological samples per population from three independent sortings were processed for RNA-seq.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis

Pre-processing of the RNA-seq reads was performed by Otogenetic corporation. The RNA-seq reads were aligned using TopHat (version 1.3.3) and levels of gene expression were quantified using Cufflinks (version 1.3.0). Genes that did not pass the quantification status flagged by Cufflinks in either Nesretic or Nesperi cell populations were excluded from the analysis. The quantification status represents the success of the Cufflinks algorithm in quantifying expression from the RNA-seq reads that were mapped for a gene. Using Bioconductor, genes were mapped to their Entrez Gene identifiers using the org.Mm.eg.db (version 2.5.0) package and to corresponding pathways based on definitions provided by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) via the KEGG.db (version 2.5.0) annotation package. The expression data was transformed by applying a log2-transformation to the ratio of (1+Nesperi FPKM values) to (1+Nesretic FPKM values) where the constant value of 1 was added because of the frequency of zero values observed in raw data. Log fold change of Nesperi/Nesretic expression was calculated for pathways defined by the KEGG orthology system (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/get_htext?ko00001.keg) and using the HSC niche gene set defined by previous microarray studies21,22. Pathway enrichment of genes showing differential expression between Nesperi and Nesretic cells was assessed using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. P-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method which controls the false discovery rate.

EdU treatment and label-retaining assay

In vivo 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU, Invitrogen) labelling was performed as previously described with BrdU10. Briefly, Nes-GFP mice were pulsed with 1mg of EdU for 14 days followed by an EdU-free chase period of 90 days. Long bones were harvested and prepared for immunostaining. The frozen BM sections were stained with a Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed as previously described10. Briefly, BM cells were stained with surface markers, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed, permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX in PBS, and stained with anti-Ki67 antibody and Hoechst 33342 at 20 µg/mL for 30 min. After washing, cells were analysed by LSRII Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

CFU-F assay

Sorted cells (1–3×102) were seeded per well in a 12-well adherent tissue culture plate using phenol-red free α-MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 20% FBS (Hyclone), 10% MesenCult stimulatory supplement (StemCell Technologies) and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin. One-half of the media was replaced after 7 days and at day 14 cells were stained with Giemsa staining solution (EMD Chemicals).

In vivo treatments

PolyIC (5mg/kg) was injected i.p. every other day (2 doses). Mice were analysed 24 hour after the last injection. 5FU (250mg/kg) was injected i.v., and mice were analysed accordingly. For HSPC mobilization, mice received 2 (day 1), 4 (day 2), or 8 (day 4) consecutive injections of Filgrastim (Amgen) (125 µg/Kg twice a day s.c.) or saline.

Induction of CreERTM-mediated recombination and iDTR mediated cell depletion

Male mice older than 8 weeks were injected with 1mg tamoxifen (Sigma) i.p. twice a day for five consecutive days as previously described38. For diphtheria toxin (DT) mediated cell depletion, 100µg/kg of DT (Sigma) were injected i.p. 2 days after the last tamoxifen injection.

LTC-IC assay

To determine long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) numbers, serial dilutions of BMNC were plated on single-well stromal cultures; 4 weeks later each individual well was assayed for the presence of CFU-C as described48. BM HSC frequencies were estimated by the Newton-Raphson method of maximum likelihood and Poisson statistics as the reciprocal of the number of test cells that yielded a 37% negative response. LTC-IC frequencies and statistical significance were determined by using the ELDA software (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/).

Competitive reconstitution

Competitive repopulation assays were performed using the CD45.1/CD45.2 congenic system. Equivalent volumes of BM cells harvested from NG2-creERTM/iDTR or Control mice (CD45.2) were transplanted into lethally irradiated (12Gy) CD45.1 recipients with 0.3×106 competitor CD45.1 cells. CD45.1/CD45.2 chimerism of recipients’ blood was analysed up to 4 months after transplantation.

Computational modelling of HSC localization

Refer to Supplementary Fig. 4. The computational simulation was performed with MATLAB software.

Statistics

All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two samples were done using the unpaired Student’s t tests. One-way ANOVA analyses followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used for multiple group comparisons. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used for comparisons of distribution patterns. Statistical analyses were performed with Graph Pad Prism 6 or MATLAB software. * P <0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Supplementary Material

a,b, Immunofluorescence images of the BM from wild-type mice stained with anti-NG2 antibody in a sectioned femur (a) and a whole-mount sternum (b). c–f, Whole-mount immunofluorescence (c–e) and FACS (f) analyses of the BM from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-αSMA (c,d) or anti-NG2 (e,f) antibodies. g–i, Analysis of the BM from NG2-creERTM / loxp-Tomato / Nes-GFP Tg mice. Whole-mount images of sternal BM (g,i) and recombination efficiency for Tomato protein expression on Nesperi cells analysed by whole-mount imaging after Tamoxifen treatment (h). Arrowheads denote Nesretic cells, arrows show Nesperi cells. n = 6 mice. Scale bar: 50 µm.

a, Computational simulation of randomly distributed HSCs on images of whole-mount prepared sterna. To establish the null-model, binary spatial maps of the sinusoids, arterioles (marked by Nes-GFPbright cells, details in Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2d,e, 5a–h) were defined from the images of whole-mount prepared sterna. To simulate a null model in which HSCs are not preferentially localized in the marrow, we randomly placed 20 HSCs (to reflect the mean HSCs/sternum observed in situ) on the unoccupied regions of the spatial maps and measured the Euclidean distance of HSCs to the nearest vascular structure. The means of 1,000 simulations defined a distribution of mean distances one would observe for non-preferentially localized HSCs in relation to the respective structures. If the in situ distance measurements were not-statistically significantly different from those obtained by a random placement of HSCs on the same structures in silica, this would indicate a non-preferential spatial HSC distribution. The cumulative probability P(X ≤ µ) of observing the in situ mean X was calculated based on the normal distribution, N(µ,σ2), with mean(µ) ± s.d.(σ) obtained from our simulation on a map of each bone marrow structure. b,c, Illustrative examples depicting measurements of randomly placed HSCs (b), and distributions of actual (white) and randomly placed (red) HSCs (c) on the image in Figure 1f.

a, Whole-mount immunofluorescence technique of the sternal BM. Tissue preparation and representative images of the vasculature and haematopoietic cells. b, Analysis of the localization of sinusoids, arterioles and HSCs in the femoral BM of transverse-shaved whole-mount immunofluorescence images. The central vein was identified and localization of sinusoids, arterioles and HSCs were plotted on the axis between central vein and bone as a ratio from 0 to 1. c, Representative FACS plots of BM CD45− Ter119− stromal cells of 3 independent experiments. Anti-Sca-1 antibody administered i.v. stains a fraction of CD31+ endothelial cells while CD31− cells are not stained. d,e, Haematopoietic (d) or Nes-GFPbright mesenchymal (e) progenitor cells are not stained by i.v. injected anti-Sca-1 antibody. f, Average distances between individual sinusoidal vessels in the femoral BM. n = 6 mice.

a, FACS plots of BM endothelial cells. BM endothelial cells are identified as a VEGFR2+ CD31+ population. Representative data of 3 mice. ~90% of BM endothelial cells are VEGFR2+ VEGFR3+ Sca-1lo (sinusoidal) and ~10% are VEGFR2+ VEGFR3− Sca-1hi (arteriolar). b, Whole-mount images of femoral BM from Tie2-GFP mice stained with anti-VEGFR3, anti-Sca-1, anti-VE-cadherin and anti-PECAM-1 antibodies. Scale bar: 25 µm. c, Whole-mount images of the sternal BM stained with Alexa Fluor633 and Dil-Ac-LDL in vivo. Alexa Fluor633+ arteriolar vessels do not take up Dil-Ac-LDL. Scale bar: 50 µm. d,e, Whole-mount images of sternal (d) and transverse-shaved femoral (e) BM from Nes-GFP mice stained with Alexa Fluor633 in vivo (d,e) and anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin antibodies (e). Alexa Fluor633 specifically stains vessels accompanied by Nes-GFPbright cells (arterioles). Scale bar: 50 µm. f, Intravital imaging of the mouse calvarial BM stained with i.v. injected Rhodamine 6G and Alexa Fluor633. Sinusoidal vessels identified by Rhodamine 6G are not stained with Alexa Fluor633. Scale bar: 100 µm.

a, Illustrative example of transverse-shaved femoral BM. Arrowheads denote HSCs. Scale bar: 100 µm. b,c, Strategy to identify phenotypic CD150+ CD41− CD48− Lineage− HSCs. Megakaryocytes are distinguished by their size and CD41 expression. b, Two representative areas highlighted in dashed squares in Fig. 1f are shown in high magnification. Arrowheads denote HSCs, arrows show CD150+ Lin/CD48/CD41+ cells. Scale bar: 50 µm. c, 3D-reconstructed images. Grid: 50 µm. d, Estimated HSC number per sternal segment measured by FACS and whole-mount image analysis. e,f, Distances of HSCs to Nes-GFPbright cells, Nes-GFPdim(n = 98 HSCs from 5 mice), arterioles or sinusoids (n = 119 HSCs from 5 mice) shown in absolute numbers (e) and absolute numbers of adjacent HSCs to those structures (f) per sternal segment (75µm thickness). Similar distribution patterns were obtained when plotting distances of HSCs from Nes-GFPperi cells or arterioles (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.97), and from Nes-GFPdim cells or sinusoids (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.45).

a, FACS analysis for HSC (CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− gated) cell cycle by using Ki-67 and Hoechst 33342 staining after Poly (I:C) injection. n = 4, 6 mice. b, HSC localization relative to Nesperi cells after Poly (I:C) treatment. n = 106, 123 HSCs from 9, 4 mice. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.007. c, Altered distances of HSCs from arterioles in Pml−/− sternal BM. n = 118, 146 HSCs from 5, 4 mice. WT / Pml−/−: 32.9±5.4% / 11.5±4.2% in 0–20µm proximity, 25.4±3.4% / 51.1±6.8% >80µm distance. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 1.9×10−6. d,e, Quantification of distances of Ki-67− quiescent (d; n = 68, 73 HSCs from 5,4 mice per group) and Ki-67+ non-quiescent (e; n = 53, 73 HSCs from 5,4 mice per group) HSCs from arteriolar niches in Pml−/− BM. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 9.6×10−8 (d), P=0.48 (e). f, Localization of HSCs relative to Nesperi cells in the sternal BM after G-CSF treatment. n = 98, 73, 122, 94 HSCs from 6, 3, 4, 5 mice per group. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Day 1 P=0.026, Day 2 P=0.012, Day 4 P=0.23 compared to control. g, Absolute numbers of HSCs that located within 20µm distance from Nesperi cells in the sternal BM after G-CSF treatment. n = 6, 3, 4, 5 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

a, FACS plots of HSC cell cycle analysed by staining with anti-Ki-67 antibody and Hoechst 33342. Representative data of 5 mice. b,c, Percentages of cells adjacent to Nesperi cells in total or EdU+ HSCs in the long-bone BM (b; n = 244, 52 HSCs from 3 mice) and in Ki-67− or Ki-67+ HSCs in the sternal BM (c; n = 64, 116 HSCs from 7 mice). d, Localization of Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs relative to arterioles in the sternal BM shown as number per sternum segment (75µm thickness). n = 64, 116 HSCs from 7 mice. e, Distributions of distances of HSCs from arterioles, bone or Col2.3-GFP+ osteoblasts. n = 109, 109, 121 HSCs from 5, 5, 3 mice. f, Probability distribution of the mean distances from 1,000 simulations of 20 randomly positioned HSCs from Col2.3-GFP+ cells (Fig. 4e). A dashed line depicts the actual mean distance observed in situ. A solid line and dotted lines show the mean ± 2 s.d. (95% confidential interval) calculated by the simulation. The observed mean distance of HSCs was not significantly different from that predicted by the simulation (P = 0.33). g, Localization of total, Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs relative to Col2.3-GFP+ osteoblasts shown in absolute numbers per sternum segment (75µm thickness). n = 121, 80, 41 HSCs from 3 mice. h,i, Localization of HSCs relative to Nesperi cells after 5FU treatment shown in number per sternum segment (75µm thickness). Distribution of HSCs (h), kinetics of the number of HSCs located within 20 µm from Nesperi cells compared to total HSCs (h, inset) and adjacent cells (i). n = 98, 39, 70, 55, 112 HSCs from 5, 9, 7, 4, 4 mice per group.

a, Quantification of GFP fluorescence intensity of Nes-GFP+ cells by whole-mount imaging of the femoral BM. Two distinct populations, Nes-GFPbright and Nes-GFPdim, can be distinguished based on fluorescence intensity. n = 423 cells from 4 mice. b, The absolute numbers of Nes-GFPbright (Nesperi) and Nes-GFPdim (Nesretic) cells in the femoral BM analysed by FACS. n = 3 mice. c–f, Whole-mount images of longitudinally shaved femoral BM from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin and anti-Sca-1 antibodies in vivo. Low power overview (c) and enlarged images (d–f). Scale bar: 100 µm (c), 50 µm (d), 25 µm (e,f). g, Whole-mount images of sternum from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-PECAM-1 and anti-VE-cadherin (c), showing morphological differences of arterioles (arrows) and sinusoids (arrowheads). h, Whole-mount images of transverse-shaved femoral BM from Nes-GFP mice, stained with anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin in vivo. Scale bar: 10 µm. i, Whole-mount images of the Nes-GFP mouse sternum stained with anti-VE-cadherin and anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibodies. Scale bar: 50 µm. j, Quantification of CFU-F content of Nes− CD31−, Nesretic and Nesperi stromal cells. n = 4 mice per group. k, Q-PCR analysis of HSC niche related genes within Nesperi, Nesretic and Nes-GFP− CD31− stromal cells. n = 8, 9, 10, 9, 6 independent experiments. * P <0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

a–c, Analyses of the BM from Lepr-cre / loxp-Tomato / Nes-GFP Tg mice. Whole-mount immunofluorescence images of sternum (a,b) and FACS analysis of the femoral BM (c). Representative data of 3 mice. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Functional analyses of NG2+ cells using NG2-creERTM / iDTR mice. a–c, Quantification of Nesperi cells (a) and vascular volume (b,c), accessed by whole mount imaging of the sternal BM from NG2-creERTM / iDTR / Nes-GFP mice. Scale Bar: 100 µm. n = 3 mice per group. d,e, Cxcl12, Kitl and Angpt1 gene expressions assessed by Q-PCR in sorted Sca-1hi arteriolar (d) and Sca-1lo sinusoidal (e) endothelial (CD45− Ter119− CD31+) cells after NG2+ cell depletion. n = 4 mice per group. f, HSC localization relative to sinusoids in the sternal BM. n = 69, 71 HSCs from 3, 4 mice per group. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P=0.29. g, Quantification of BM cellularity, frequency and number of phenotypic CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− HSCs in spleen. n = 6 mice per group. h,i, Quantification of long-term reconstituting HSCs by LTC-IC assays. n = 3 mice per group. j, Numbers of total leukocytes and phenotypic CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− HSCs in blood. n = 3 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. P.P. Pandolfi for providing Pml−/− mice, D. Rowe, J. Butler, S.Rafii for providing Col2.3-GFP mice. We are grateful to L. Tesfa and O. Uche for technical assistance with sorting. S.P. is supported by a New York Stem Cell Foundation-Druckenmiller Fellowship and C.S. by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (Emmy-Noether-Program). J.A. was supported from Training Grant T32 063754. This work was enabled by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 grants DK056638, HL069438, HL097700) to P.S.F.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions

Y.K. and C.S. performed the whole-mount imaging experiments and analysed the data; I.B. and S.P. performed FACS sorting and Q-PCR analyses; J.A. and A.B. performed computational modelling and statistical analysis of the data; D.Z. analysed NG2-creERTM/iDTR mice; T.M. performed the imaging experiments in BM sections; Q.W. and J.C.M. analysed the RNA-seq data; D.L. performed LTC-IC assay and characterization of endothelial cells by FACS; K.I. provided mice and interpreted data; P.S.F. initiated and directed the study. Y.K. and P.S.F. wrote the manuscript. All of the authors contributed to the design of experiments, discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Author Information

The RNA sequencing data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE48764.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu YC, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell. 2011;144:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orford KW, Scadden DT. Deconstructing stem cell self-renewal: genetic insights into cell-cycle regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:115–128. doi: 10.1038/nrg2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng T, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito K, et al. PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2008;453:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature07016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essers MA, et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458:904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature07815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato T, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-2 protects quiescent hematopoietic stem cells from type I interferon-dependent exhaustion. Nat Med. 2009;15:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nm.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Passegue E, Wagers AJ, Giuriato S, Anderson WC, Weissman IL. Global analysis of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression in the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fates. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:1599–1611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Goodell MA. Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-gamma in response to chronic infection. Nature. 2010;465:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nature09135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugimura R, et al. Noncanonical Wnt signaling maintains hematopoietic stem cells in the niche. Cell. 2012;150:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai F, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson SK, et al. Osteopontin, a key component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and regulator of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1232–1239. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stier S, et al. Osteopontin is a hematopoietic stem cell niche component that negatively regulates stem cell pool size. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1781–1791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omatsu Y, et al. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendez-Ferrer S, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ema H, Suda T. Two anatomically distinct niches regulate stem cell activity. Blood. 2012;120:2174–2181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooper AT, et al. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell stem cell. 2009;4:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nombela-Arrieta C, et al. Quantitative imaging of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell localization and hypoxic status in the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:533–543. doi: 10.1038/ncb2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li XM, Hu Z, Jorgenson ML, Slayton WB. High levels of acetylated low-density lipoprotein uptake and low tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin and epidermal growth factor homology domains-2 (Tie2) promoter activity distinguish sinusoids from other vessel types in murine bone marrow. Circulation. 2009;120:1910–1918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.871574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Z, Lu Z, Chhatbar PY, O'Herron P, Kara P. An artery-specific fluorescent dye for studying neurovascular coupling. Nat Methods. 2012;9:273–276. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takaku T, et al. Hematopoiesis in 3 dimensions: human and murine bone marrow architecture visualized by confocal microscopy. Blood. 2010;116:e41–e55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naveiras O, et al. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature. 2009;460:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature08099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katayama Y, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamazaki S, et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2011;147:1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharya D, et al. Niche recycling through division-independent egress of hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2837–2850. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalajzic Z, et al. Directing the expression of a green fluorescent protein transgene in differentiated osteoblasts: comparison between rat type I collagen and rat osteocalcin promoters. Bone. 2002;31:654–660. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00912-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu F, et al. Csf3r mutations in mice confer a strong clonal HSC advantage via activation of Stat5. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:946–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI32704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenbaum AM, Link DC. Mechanisms of G-CSF-mediated hematopoietic stem and progenitor mobilization. Leukemia. 2011;25:211–217. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birbrair A, et al. Skeletal muscle pericyte subtypes differ in their differentiation potential. Stem Cell Res. 2012;10:67–84. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X, et al. Age-dependent fate and lineage restriction of single NG2 cells. Development. 2011;138:745–753. doi: 10.1242/dev.047951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chi JT, et al. Endothelial cell diversity revealed by global expression profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10623–10628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1434429100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frenette PS, Pinho S, Lucas D, Scheiermann C. Mesenchymal Stem Cell: Keystone of the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche and a Stepping-Stone for Regenerative Medicine. Annual review of immunology. 2013 doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenbaum A, et al. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature. 2013;495:227–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding L, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature. 2013;495:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sipkins DA, et al. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature. 2005;435:969–973. doi: 10.1038/nature03703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winkler IG, et al. Vascular niche E-selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance. Nat Med. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nm.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mignone JL, Kukekov V, Chiang AS, Steindler D, Enikolopov G. Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References (ON LINE ONLY)

- 46.Kawamoto T. Use of a new adhesive film for the preparation of multi-purpose fresh-frozen sections from hard tissues, whole-animals, insects and plants. Arch Histol Cytol. 2003;66:123–143. doi: 10.1679/aohc.66.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiang EY, Hidalgo A, Chang J, Frenette PS. Imaging receptor microdomains on leukocyte subsets in live mice. Nat Methods. 2007;4:219–222. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller CL, Dykstra B, Eaves CJ. Characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2008;Chapter 22(Unit 22B):22. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im22b02s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

a,b, Immunofluorescence images of the BM from wild-type mice stained with anti-NG2 antibody in a sectioned femur (a) and a whole-mount sternum (b). c–f, Whole-mount immunofluorescence (c–e) and FACS (f) analyses of the BM from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-αSMA (c,d) or anti-NG2 (e,f) antibodies. g–i, Analysis of the BM from NG2-creERTM / loxp-Tomato / Nes-GFP Tg mice. Whole-mount images of sternal BM (g,i) and recombination efficiency for Tomato protein expression on Nesperi cells analysed by whole-mount imaging after Tamoxifen treatment (h). Arrowheads denote Nesretic cells, arrows show Nesperi cells. n = 6 mice. Scale bar: 50 µm.

a, Computational simulation of randomly distributed HSCs on images of whole-mount prepared sterna. To establish the null-model, binary spatial maps of the sinusoids, arterioles (marked by Nes-GFPbright cells, details in Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2d,e, 5a–h) were defined from the images of whole-mount prepared sterna. To simulate a null model in which HSCs are not preferentially localized in the marrow, we randomly placed 20 HSCs (to reflect the mean HSCs/sternum observed in situ) on the unoccupied regions of the spatial maps and measured the Euclidean distance of HSCs to the nearest vascular structure. The means of 1,000 simulations defined a distribution of mean distances one would observe for non-preferentially localized HSCs in relation to the respective structures. If the in situ distance measurements were not-statistically significantly different from those obtained by a random placement of HSCs on the same structures in silica, this would indicate a non-preferential spatial HSC distribution. The cumulative probability P(X ≤ µ) of observing the in situ mean X was calculated based on the normal distribution, N(µ,σ2), with mean(µ) ± s.d.(σ) obtained from our simulation on a map of each bone marrow structure. b,c, Illustrative examples depicting measurements of randomly placed HSCs (b), and distributions of actual (white) and randomly placed (red) HSCs (c) on the image in Figure 1f.

a, Whole-mount immunofluorescence technique of the sternal BM. Tissue preparation and representative images of the vasculature and haematopoietic cells. b, Analysis of the localization of sinusoids, arterioles and HSCs in the femoral BM of transverse-shaved whole-mount immunofluorescence images. The central vein was identified and localization of sinusoids, arterioles and HSCs were plotted on the axis between central vein and bone as a ratio from 0 to 1. c, Representative FACS plots of BM CD45− Ter119− stromal cells of 3 independent experiments. Anti-Sca-1 antibody administered i.v. stains a fraction of CD31+ endothelial cells while CD31− cells are not stained. d,e, Haematopoietic (d) or Nes-GFPbright mesenchymal (e) progenitor cells are not stained by i.v. injected anti-Sca-1 antibody. f, Average distances between individual sinusoidal vessels in the femoral BM. n = 6 mice.

a, FACS plots of BM endothelial cells. BM endothelial cells are identified as a VEGFR2+ CD31+ population. Representative data of 3 mice. ~90% of BM endothelial cells are VEGFR2+ VEGFR3+ Sca-1lo (sinusoidal) and ~10% are VEGFR2+ VEGFR3− Sca-1hi (arteriolar). b, Whole-mount images of femoral BM from Tie2-GFP mice stained with anti-VEGFR3, anti-Sca-1, anti-VE-cadherin and anti-PECAM-1 antibodies. Scale bar: 25 µm. c, Whole-mount images of the sternal BM stained with Alexa Fluor633 and Dil-Ac-LDL in vivo. Alexa Fluor633+ arteriolar vessels do not take up Dil-Ac-LDL. Scale bar: 50 µm. d,e, Whole-mount images of sternal (d) and transverse-shaved femoral (e) BM from Nes-GFP mice stained with Alexa Fluor633 in vivo (d,e) and anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin antibodies (e). Alexa Fluor633 specifically stains vessels accompanied by Nes-GFPbright cells (arterioles). Scale bar: 50 µm. f, Intravital imaging of the mouse calvarial BM stained with i.v. injected Rhodamine 6G and Alexa Fluor633. Sinusoidal vessels identified by Rhodamine 6G are not stained with Alexa Fluor633. Scale bar: 100 µm.

a, Illustrative example of transverse-shaved femoral BM. Arrowheads denote HSCs. Scale bar: 100 µm. b,c, Strategy to identify phenotypic CD150+ CD41− CD48− Lineage− HSCs. Megakaryocytes are distinguished by their size and CD41 expression. b, Two representative areas highlighted in dashed squares in Fig. 1f are shown in high magnification. Arrowheads denote HSCs, arrows show CD150+ Lin/CD48/CD41+ cells. Scale bar: 50 µm. c, 3D-reconstructed images. Grid: 50 µm. d, Estimated HSC number per sternal segment measured by FACS and whole-mount image analysis. e,f, Distances of HSCs to Nes-GFPbright cells, Nes-GFPdim(n = 98 HSCs from 5 mice), arterioles or sinusoids (n = 119 HSCs from 5 mice) shown in absolute numbers (e) and absolute numbers of adjacent HSCs to those structures (f) per sternal segment (75µm thickness). Similar distribution patterns were obtained when plotting distances of HSCs from Nes-GFPperi cells or arterioles (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.97), and from Nes-GFPdim cells or sinusoids (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.45).

a, FACS analysis for HSC (CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− gated) cell cycle by using Ki-67 and Hoechst 33342 staining after Poly (I:C) injection. n = 4, 6 mice. b, HSC localization relative to Nesperi cells after Poly (I:C) treatment. n = 106, 123 HSCs from 9, 4 mice. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 0.007. c, Altered distances of HSCs from arterioles in Pml−/− sternal BM. n = 118, 146 HSCs from 5, 4 mice. WT / Pml−/−: 32.9±5.4% / 11.5±4.2% in 0–20µm proximity, 25.4±3.4% / 51.1±6.8% >80µm distance. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 1.9×10−6. d,e, Quantification of distances of Ki-67− quiescent (d; n = 68, 73 HSCs from 5,4 mice per group) and Ki-67+ non-quiescent (e; n = 53, 73 HSCs from 5,4 mice per group) HSCs from arteriolar niches in Pml−/− BM. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P = 9.6×10−8 (d), P=0.48 (e). f, Localization of HSCs relative to Nesperi cells in the sternal BM after G-CSF treatment. n = 98, 73, 122, 94 HSCs from 6, 3, 4, 5 mice per group. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Day 1 P=0.026, Day 2 P=0.012, Day 4 P=0.23 compared to control. g, Absolute numbers of HSCs that located within 20µm distance from Nesperi cells in the sternal BM after G-CSF treatment. n = 6, 3, 4, 5 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

a, FACS plots of HSC cell cycle analysed by staining with anti-Ki-67 antibody and Hoechst 33342. Representative data of 5 mice. b,c, Percentages of cells adjacent to Nesperi cells in total or EdU+ HSCs in the long-bone BM (b; n = 244, 52 HSCs from 3 mice) and in Ki-67− or Ki-67+ HSCs in the sternal BM (c; n = 64, 116 HSCs from 7 mice). d, Localization of Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs relative to arterioles in the sternal BM shown as number per sternum segment (75µm thickness). n = 64, 116 HSCs from 7 mice. e, Distributions of distances of HSCs from arterioles, bone or Col2.3-GFP+ osteoblasts. n = 109, 109, 121 HSCs from 5, 5, 3 mice. f, Probability distribution of the mean distances from 1,000 simulations of 20 randomly positioned HSCs from Col2.3-GFP+ cells (Fig. 4e). A dashed line depicts the actual mean distance observed in situ. A solid line and dotted lines show the mean ± 2 s.d. (95% confidential interval) calculated by the simulation. The observed mean distance of HSCs was not significantly different from that predicted by the simulation (P = 0.33). g, Localization of total, Ki-67− and Ki-67+ HSCs relative to Col2.3-GFP+ osteoblasts shown in absolute numbers per sternum segment (75µm thickness). n = 121, 80, 41 HSCs from 3 mice. h,i, Localization of HSCs relative to Nesperi cells after 5FU treatment shown in number per sternum segment (75µm thickness). Distribution of HSCs (h), kinetics of the number of HSCs located within 20 µm from Nesperi cells compared to total HSCs (h, inset) and adjacent cells (i). n = 98, 39, 70, 55, 112 HSCs from 5, 9, 7, 4, 4 mice per group.

a, Quantification of GFP fluorescence intensity of Nes-GFP+ cells by whole-mount imaging of the femoral BM. Two distinct populations, Nes-GFPbright and Nes-GFPdim, can be distinguished based on fluorescence intensity. n = 423 cells from 4 mice. b, The absolute numbers of Nes-GFPbright (Nesperi) and Nes-GFPdim (Nesretic) cells in the femoral BM analysed by FACS. n = 3 mice. c–f, Whole-mount images of longitudinally shaved femoral BM from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin and anti-Sca-1 antibodies in vivo. Low power overview (c) and enlarged images (d–f). Scale bar: 100 µm (c), 50 µm (d), 25 µm (e,f). g, Whole-mount images of sternum from Nes-GFP mice stained with anti-PECAM-1 and anti-VE-cadherin (c), showing morphological differences of arterioles (arrows) and sinusoids (arrowheads). h, Whole-mount images of transverse-shaved femoral BM from Nes-GFP mice, stained with anti-PECAM-1, anti-VE-cadherin in vivo. Scale bar: 10 µm. i, Whole-mount images of the Nes-GFP mouse sternum stained with anti-VE-cadherin and anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibodies. Scale bar: 50 µm. j, Quantification of CFU-F content of Nes− CD31−, Nesretic and Nesperi stromal cells. n = 4 mice per group. k, Q-PCR analysis of HSC niche related genes within Nesperi, Nesretic and Nes-GFP− CD31− stromal cells. n = 8, 9, 10, 9, 6 independent experiments. * P <0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

a–c, Analyses of the BM from Lepr-cre / loxp-Tomato / Nes-GFP Tg mice. Whole-mount immunofluorescence images of sternum (a,b) and FACS analysis of the femoral BM (c). Representative data of 3 mice. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Functional analyses of NG2+ cells using NG2-creERTM / iDTR mice. a–c, Quantification of Nesperi cells (a) and vascular volume (b,c), accessed by whole mount imaging of the sternal BM from NG2-creERTM / iDTR / Nes-GFP mice. Scale Bar: 100 µm. n = 3 mice per group. d,e, Cxcl12, Kitl and Angpt1 gene expressions assessed by Q-PCR in sorted Sca-1hi arteriolar (d) and Sca-1lo sinusoidal (e) endothelial (CD45− Ter119− CD31+) cells after NG2+ cell depletion. n = 4 mice per group. f, HSC localization relative to sinusoids in the sternal BM. n = 69, 71 HSCs from 3, 4 mice per group. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P=0.29. g, Quantification of BM cellularity, frequency and number of phenotypic CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− HSCs in spleen. n = 6 mice per group. h,i, Quantification of long-term reconstituting HSCs by LTC-IC assays. n = 3 mice per group. j, Numbers of total leukocytes and phenotypic CD150+ CD48− Sca-1+ c-kit+ Lineage− HSCs in blood. n = 3 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.