Abstract

Relationships among Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms and adult personality traits have not been examined in larger clinically diagnosed samples. We collected multi-source ADHD symptom and self-report NEO Five-Factor Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992a) data from 117 adults with ADHD and tested symptom-trait associations using structural equation modeling. The final model fit the data. Inattention was positively associated with Neuroticism and negatively associated with Conscientiousness. Based on ADHD expression in adulthood, hyperactivity and impulsivity were estimated as separate constructs and showed differential relationships to Extraversion and Agreeableness. A significant positive relationship between Hyperactivity and Conscientiousness arose in the context of other pathways. ADHD symptoms are reliably associated with personality traits, suggesting a complex interplay across development that warrants prospective study into adulthood.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, personality, Five Factor model, NEO-FFI, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a valid and prevalent disorder that lasts into adulthood in a majority of cases, is associated with significant impairment in major functional domains, and confers increased risk for psychiatric comorbidity (Barkley et al, 2008). In the DSM-IV diagnostic system developed for children, the disorder is characterized by two symptom dimensions—inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity—that define three subtypes of ADHD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Several studies have supported a three-factor model of adult ADHD symptoms that separates hyperactive from impulsive symptoms, the latter primarily reflecting verbal impulsivity (Barkley et al, 2008; Glutting et al, 2005; Knouse et al, 2009; Kooij et al, 2004; Span et al, 2002). The current study examines the association between these three symptom dimensions and personality traits in clinically diagnosed adults.

A thorough understanding of personality traits in adult ADHD has important theoretical implications. Theoretical accounts of ADHD have largely focused on cognitive and neuropsychological deficits (Barkley, 1997; Douglas, 1998; Rapport et al, 2008), but Nigg and Casey (2005) outlined a developmental theory that integrates a temperament-based account of the disorder. Nigg (2006; pp. 182–185), explains that the development of self-regulation involves motivational/affective and controlled/executive processes and that ADHD may arise from pathways related to one or both processes. Because these processes map onto dimensions of personality, understanding the relationship between ADHD symptoms and traits provides support to temperament-based accounts (Nigg et al., 2002). Comparing interrelationships between ADHD symptoms and personality traits in different developmental periods would clarify which traits represent outcomes of ADHD versus different manifestations of the same core features (Miller et al, 2008; Nigg et al, 2002b). Understanding these processes may also shed light on the mechanisms behind increased risk for comorbid disorders in adults with ADHD (Clark et al, 1994).

Six previous studies examined Five Factor Model (FFM) personality traits in non-clinical and small clinical adult samples (Braaten et al, 1997; Jacob et al, 2007; McKinney et al, 2012; Nigg et al, 2002a; Parker et al, 2004; Ranseen et al, 1998). Across studies, ADHD symptoms have been associated with lower Conscientiousness and higher Neuroticism. Associations with lower Agreeableness and, less frequently, higher Extraversion have also been reported. Nigg and colleagues (2002) conducted the largest set of studies of ADHD and personality using the NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa et al, 1992a). Across two undergraduate samples, three community samples of parents, and one sample that included clinically diagnosed adults, higher reports of childhood ADHD symptoms were associated with lower Conscientiousness, lower Agreeableness, and higher Neuroticism. Associations with inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were examined in three of the samples. Inattention was consistently related to lower Conscientiousness and higher Neuroticism while hyperactivity-impulsivity was related to lower Agreeableness. Hyperactivity-impulsivity was related to higher Extraversion in the sample with clinically diagnosed adults. Also in this sample, current attention problems were related to lower Conscientiousness and higher Neuroticism and intrusive behavior was related to lower Agreeableness, higher Extraversion, and higher Neuroticism.

More recently, Jacob et al (2007) compared scores on the NEO-Personality Inventory, Revised (Costa et al, 1992b) to scale norms and controls in a sample of 372 adults with clinically diagnosed ADHD. While they did identify higher Neuroticism and Lower Conscientiousness in the ADHD group, in contrast to prior findings, their sample showed normative levels of Agreeableness and lower levels of Extraversion. The study did not examine relationships between symptom dimensions and personality traits.

The current study examines the extent to which conclusions drawn from general population samples and small clinical samples of adults with ADHD apply to people in the upper tail of the ADHD symptom distribution—individuals with a clinical ADHD diagnosis. We wish to know whether patterns generalize to those adults for whom personality-based theories may predict the most severe symptoms and the most significant impairment. In addition, we employ the three-factor model of ADHD symptoms emerging from studies of adult symptomatology but not yet applied in personality studies.

FFM personality traits were measured in a sample of clinically diagnosed adults receiving medication treatment for ADHD but still displaying symptoms severe enough to warrant additional treatment. Our first aim was to compare the personality profile of this clinical sample to the normative sample. Our second aim was to model the relationships among ADHD symptom dimensions and personality traits within this sample, extending and expanding upon the work of Nigg and colleagues (2002b). Structural equation modeling (SEM) using a three-factor model of ADHD symptoms allowed us to evaluate ADHD-personality relationships simultaneously, to adjust for measurement error in the assessment of ADHD symptoms, and to identify unique pathways. We modeled adult ADHD symptoms as exogenous predictors of FFM traits because ADHD is a developmental disorder that, by definition, has persisted since childhood and is likely to influence the patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that constitute adult personality. We hypothesized that inattention would predict lower Conscientiousness and higher Neuroticism and that hyperactivity and impulsivity would predict lower Agreeableness. We also tested the associations of hyperactivity and impulsivity with Extraversion and Neuroticism as findings concerning these relationships have been reported less consistently.

Method

Participants

Fifty-nine men and 58 women (N = 117; age 18 – 65) completed baseline assessment for one of two studies of cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD at a large New England hospital (Safren et al, 2005; Safren et al, 2010). All participants had a pre-existing ADHD diagnosis from a provider outside of the study and were being treated with medications for ADHD, but continued to meet full criteria for the disorder confirmed by structured clinical interview (Orvaschel, 1985). Details of clinical assessment procedures are described in Safren et al. (2010).

Measures

Clinician-rated measure

A Ph.D.-level clinical assessor completed the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS; Barkley, 1990; DuPaul, 1990) which, modified for DSM-IV, assesses each of the 18 symptoms of ADHD using a four-point severity grid (0=not present; 1=mild, 2=moderate; 3=severe). For approximately one-third of the patients who completed the first of the two treatment studies, the assessor had over 10 years of supervised experience with the ADHD-RS and the interviews using the measures were audio taped and a subset of tapes reviewed and discussed with another Ph.D. – level clinician. For the remaining patients in the second study, the assessor had over 10 years of experience with structured interviews and ratings scales for mood and anxiety disorders, and received extensive training on the ADHD-RS and all sessions were audio taped. Tapes were regularly reviewed by one of two Ph.D.-level supervisors and no significant discrepancies in ratings occurred that necessitated changes to the original ratings. Three subscales were derived from this measure based on prior factor analysis (Knouse et al, 2009). Internal consistency (α) was .57 for inattention (5 items), .64 for impulsivity (6 items), and .73 for hyperactivity (7 items).

Self-report measures

Participants rated the frequency of the 18 ADHD symptoms using the Current Symptoms Scale (CSS; Barkley et al, 2006). Items are rated on a 4-point scale (“Never or Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” or “Very Often”). Internal consistency (α) for subscales identified in the factor analysis by Knouse et al (2009) was .71 for inattention (6 items), .83 for impulsivity (9 items), and .83 for hyperactivity (7 items). Participants completed the NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa et al, 1992a), a 60-item scale assessing each of the FFM personality domains. Each domain is assessed by 12 items. Participants with missing data on more than two items in any subscale were not included. For participants with two or fewer missing values on a subscale, the mean of the other subscale items was imputed. Internal consistency (α) in the current sample was .85 for Neuroticism, .76 for Extraversion, .73 for Openness, .77 for Agreeableness, and .79 for Conscientiousness.

Procedure

Participants completed a diagnostic evaluation to confirm study eligibility, a baseline clinician assessment of ADHD symptom severity, and a battery of self-report questionnaires. Participants first completed a diagnostic evaluation with a Ph.D.-level clinician or pre-doctoral clinical psychology intern to confirm the diagnosis of ADHD and determine study eligibility. This first assessor administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First et al, 1995), supplemented by ADHD sections of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel, 1985). In previous studies conducted in an affiliated clinic, diagnostic reliability of ADHD diagnoses using this instrument has been high (Kappa=1.0, 95% confidence interval=0.8–1.0) (Spencer et al, 1995). Participants were required to meet DSM-IV criteria in their report of childhood and current symptoms and functional impairment.

Participants then completed a separate baseline assessment prior to randomization to treatment condition, which included the ADHD-RS described above administered by a second Ph.D.- level clinical assessor.

Statistical Analysis

Structural equation modeling in Amos 18 (SPSS, Inc.) was used to test relationships between ADHD symptom dimensions and NEO personality subscales. Parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) approach to missing data, in which data are assumed to be missing at random (Schafer et al, 2002). Based on current recommendations to minimize Type I and II errors, we relied on multiple indices to evaluate overall model fit: chi-square (χ2) statistic, comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Taken together a χ2 p-value>.05, CFI>.95, and RMSEA<.06 are considered to reflect good model fit and were used in the current study to justify interpretation of model parameters (Hu et al, 1999).

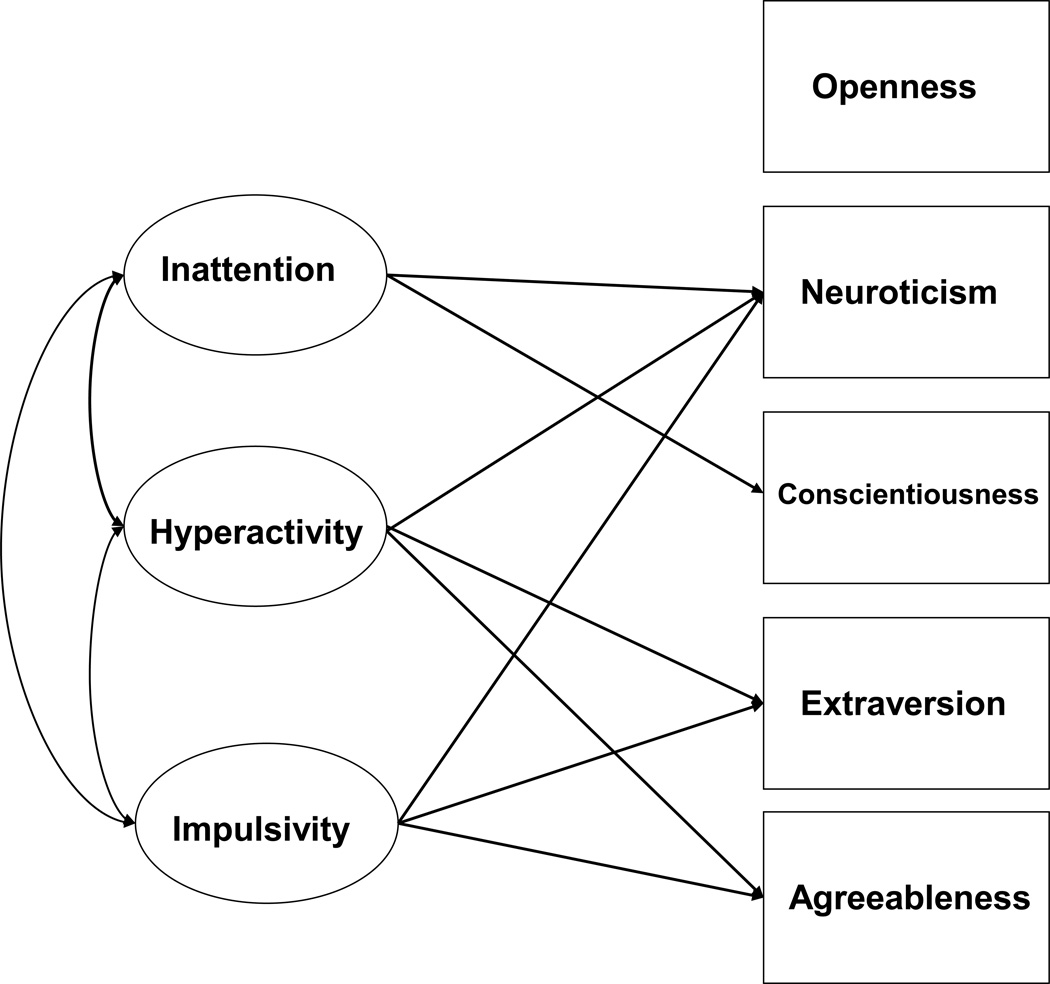

In the hypothesized conceptual model (Figure 1), each ADHD symptom dimension (inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity) was tested as a latent variable with two indicators (investigator rating and self-report rating). In a two-step approach (Anderson et al, 1988), we first evaluated the measurement model of ADHD symptom dimensions prior to testing hypothesized structural paths between dimensions and NEO personality subscales. We then tested a series of nested models in which parameters were restricted or freely estimated based on modification indices and a sound conceptual basis. The resulting differences in the χ2 statistic per degree of freedom were evaluated and changes which resulted in significant improvement in model fit were retained. This allowed us to arrive at the most parsimonious model while identifying unique relationships within this clinical sample.

Figure 1.

Model of hypothesized relationships between ADHD symptoms and FFM personality traits. Rectangles represent observed variables and ovals, latent variables. To maintain presentation clarity, latent factor indicators and covaried residual terms not shown.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Complete data were available for 117 individuals (M age= 42.85 years, SD=11.01). Race/ethnicity was primarily Caucasian (90.6%), with 5.1% African American, 2.6% Hispanic or Latino, and 0.9% Asian. Most participants (83.8%) had achieved a college degree or higher.

Correlations among the modeled variables are shown in Table 1. Adults with ADHD had mean NEO-FFI scores significantly different from the NEO FFI normative sample for four of the five scales (see Table 2). The strongest effect size was for Conscientiousness, where the mean score for the ADHD adults fell more than two standard deviations below the normative mean. ADHD adults also showed elevated Neuroticism (large effect size) and Openness to Experience (medium effect size) and lower Agreeableness (small effect size).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations (r) between Model Variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Inattention – Investigator | .30* | .36** | .49** | .27* | .22* | .20 | .07 | .12 | .04 | −.17 |

| 2. Impulsivity – Investigator | -- | .35** | .30* | .61** | .34** | .08 | .08 | .01 | −.28* | .01 |

| 3. Hyperactivity – Investigator | -- | .47** | .54** | .77** | .12 | .27* | −.17 | −.13 | .02 | |

| 4. Inattention – Self | -- | .59** | .51** | .27* | −.01 | .02 | −.09 | −.33** | ||

| 5. Impulsivity – Self | -- | .73** | .19 | .15 | −.07 | −.24* | −.08 | |||

| 6. Hyperactivity – Self | -- | .15 | .27* | −.12 | −.10 | .05 | ||||

| 7. Neuroticism | -- | −.41** | −.11 | −.40** | −.26* | |||||

| 8. Extraversion | -- | −.02 | .27* | .26* | ||||||

| 9. Openness | -- | .11 | −.18* | |||||||

| 10. Agreeableness | -- | .15 | ||||||||

| 11. Conscientiousness | -- |

p < .01;

p < .001.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Between-Group Comparisons of Personality Traits in Participants with ADHD and the NEO-FFI Normative Sample

| ADHD (n = 117) |

Normative Samplea (n = 1539) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Percentileb | M | SD | t | d | |

| Neuroticism | 26.28 | 8.25 | 82 | 19.07 | 7.68 | 9.74** | .90 |

| Extraversion | 28.53 | 6.41 | 62 | 27.69 | 5.85 | 1.49 | .13 |

| Openness | 31.28 | 6.50 | 77 | 27.03 | 5.84 | 7.53** | .69 |

| Conscientiousness | 19.69 | 6.69 | 1 | 34.57 | 5.88 | −26.12** | −2.36 |

| Agreeableness | 31.73 | 6.54 | 45 | 32.84 | 4.97 | −2.27* | −.19 |

Note. Mean scores rounded to nearest whole number when calculating percentiles. NEO-FFI = NEO Five Factor Inventory (Costa et al, 1992a); d = Cohen’s d, measure of effect size

Data obtained from Table B-4 (p. 78) in the NEO-PI-R Professional Manual (Costa et al, 1992b).

Percentiles calculated using Table C-7 (p. 85) in the NEO-PI-R Professional manual (Costa et al, 1992b).

p < .05;

p < .0001.

Measurement Modeling

We first tested a measurement model in which we allowed the three ADHD symptom latent factors and five observed NEO domains to freely correlate. The factor loading for the self-report indicator of each ADHD dimension was set to 1 to set the metric for the latent factor. When this model was tested, error variances for the three self-report indicators were estimated to be negative (Heywood cases). Following recommendations ofDillon et al. (1987), we therefore set these error variances close to zero (.005). This model converged and showed relatively poor fit (Χ2=34.21, df =21, p=.03; RMSEA=.07; CFI=.996). The impulsivity and hyperactivity latent factors were highly correlated (r=.73, p<.001), raising the possibility that these dimensions reflected a unitary construct. However, we chose to retain separate impulsivity and hyperactivity factors, supported by findings from our prior factor analytic work (Knouse et al, 2009). Self-report and clinician-rated indicators of the ADHD symptom latent constructs loaded significantly on their designated factors. With the weights for self-reported symptom dimensions set to 1, weights for investigator-rated inattentive (Standardized β=.49), hyperactive (Standardized β =.77) and impulsive (Standardized β=.61) symptoms were significant (p’s<.001). Moderate correlations among variables supported testing the hypothesized direct paths in our conceptual model.

Structural Modeling

Hypothesized Model

Based on prior work, the hypothesized model estimated direct paths including inattention predicting Conscientiousness and Neuroticism, and both hyperactivity and impulsivity predicting Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Agreeableness (Figure 1). Because individual NEO scales are best interpreted and conceptualized in the context of the other domain scales, Openness was retained in the model although no predictive paths were hypothesized. We also included covaried error terms† among NEO subscales to account for shared method variance across these self-report scales and to account for correlations observed among these scales (Costa et al, 1992b). In addition, we included covaried error terms among the investigator report scales of ADHD symptom dimensions due to shared method variance. (This was not possible for self-reports because error variances were constrained.)

Model Modifications

Model fit indices for the hypothesized model suggested inadequate fit (Χ2=50.57, df=31, p=.015; CFI=.956; RMSEA=.074). Paths from impulsivity to Neuroticism and Extraversion and from hyperactivity to Agreeableness and Neuroticism were non-significant. When these paths were constrained to zero and the revised model was tested, as expected, the constraints did not significantly worsen model fit (as indicated by a non-significant increase in Χ2 per degree of freedom gained) and were therefore retained in subsequent model iterations. The path from inattention to Neuroticism was marginally significant (p=.06) but was retained because of the importance of this relationship in prior studies.

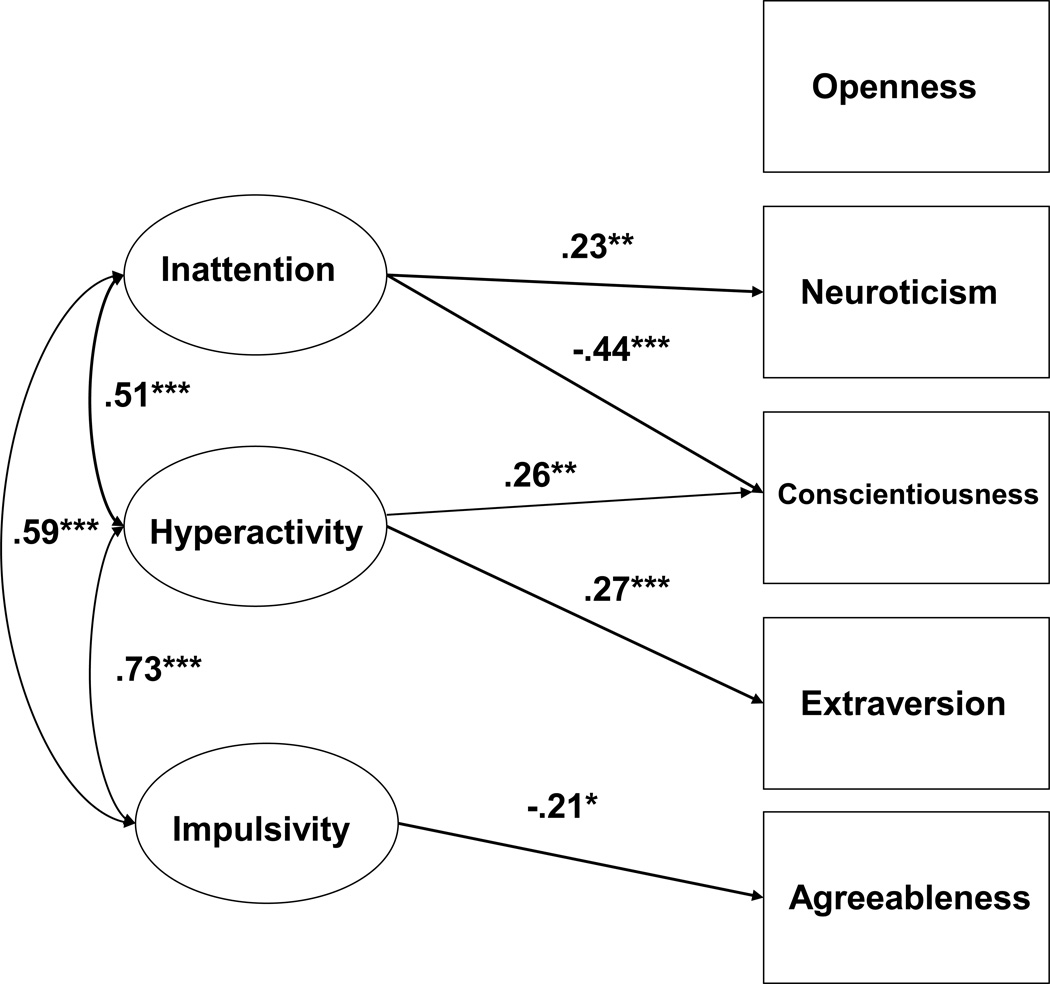

Final Model

Based on modification indices, a direct path was estimated from hyperactivity to Conscientiousness (Figure 2). This addition significantly improved model fit (as indicated by a significant reduction in Χ2 per degree of freedom lost). This final model (Figure 2) adequately fit the data (Χ2=46.32, df =34, p=.077; CFI= .972; RMSEA=.056) and explained 5.3% of the variance in Neuroticism, 14.5% in Conscientiousness, 7.4% in Extraversion, and 4.6% in Agreeableness. In the final model, the direct paths from inattention to Neuroticism (Standardized β=.23, p<.01) and Conscientiousness (Standardized β=−.44, p<.001) were significant, indicating that greater inattention predicted higher Neuroticism and lower Conscientiousness. The direct paths from hyperactivity to Conscientiousness (Standardized β=.26, p<.01) and Extraversion (Standardized β=.27, p<.001) were significant, indicating that greater hyperactivity predicted higher Conscientiousness and Extraversion. Finally, greater impulsivity predicted only lower Agreeableness (Standardized β=−.21; p<.05).

Figure 2.

Final model with standardized parameter estimates. Rectangles represent observed variables, ovals, latent factors. To maintain presentation clarity, latent factor indicators and residual terms† not shown. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Model fit statistics: Χ2= 46.32, df = 34, p = .077; CFI = .972; RMSEA = .056. R2 for Personality variables are: Neuroticism=5.3%, Conscientiousness=14.5%, Extraversion=7.4%, and Agreeableness= 4.6%. Standardized regression weights of independent assessor latent factor indicators were as follows: inattention = .49, hyperactivity = .78, impulsivity = .62, all p<.001.

Discussion

In the hypothesized model (Figure 1) we evaluated separate pathways from hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention to NEO domains. This model was based upon prior studies that evaluated hyperactivity-impulsivity as a single factor based on the DSM-IV conceptualization. Given recent studies supporting a three-factor model of adult ADHD, we examined associations of hyperactivity and impulsivity separately with personality traits, which yielded new information. In partial support of our hypotheses, impulsivity, but not hyperactivity, predicted lower Agreeableness while hyperactivity, but not impulsivity, predicted higher Extraversion. Neither of these two ADHD factors predicted Neuroticism (Figure 2). These differential relationships may support the notion that hyperactivity and impulsivity represent meaningfully distinct constructs in adults with ADHD. While these dimensions may be more closely associated in childhood, by adulthood motor hyperactivity and impulsive behavior may come to represent distinct constructs with distinct correlates. This conclusion is in line with Kessler et al.’s (2010) recent conclusion that the structure of ADHD symptoms, not just their expression, may differ in adults versus children. These results may explain why associations between ADHD and Extraversion have been inconsistent across adult studies—that is, this relationship may be masked when hyperactive and impulsive symptoms are not analyzed separately. It is important to note, however, that Extraversion was not significantly elevated in our clinical sample and this finding will need to be confirmed in future studies.

The association between impulsivity and Agreeableness replicates recent findings by McKinney et al (2012), who found a moderate negative association between impulsivity and Agreeableness in a non-clinical sample of 160 undergraduates. The relationship between impulsivity and Agreeableness may be understood in the context of Barkley’s (2010) recent assertion that emotional impulsivity and deficient emotional self-regulation are key features of ADHD and load on the same factor as ADHD impulsivity in childhood and adulthood. Impulsive emotionality likely impacts a person’s level of Agreeableness—the extent to which they are able to delay their own emotional responding to be sympathetic, caring, and compliant, with others. The angry hostility and impulsiveness facets of Neuroticism may also be related to impulsivity in adults with ADHD; however, the NEO-FFI does not allow for a comprehensive analysis of facets and thus future studies should clarify the relationships among facets of Neuroticism and ADHD impulsivity.

Our results also supported hypothesized relationships between inattention and trait Conscientiousness and Neuroticism—the most consistent findings across prior studies. Adults with ADHD in this study were characterized by lower-than-normal Conscientiousness and higher Neuroticism (Table 2). Inattention, but neither hyperactivity nor impulsivity, was positively associated with Neuroticism. The current study confirms associations noted in prior work and extends them to a sample of adults clinically diagnosed with ADHD.

Findings converge with other recent data suggesting that inattentive symptoms are most strongly associated with impairment in adults seeking treatment for ADHD. Stavro, et al. (2007) used a latent variable approach to show that inattentive-disorganized symptoms primarily accounted for adaptive impairments in young adults with ADHD, whereas hyperactive-impulsive symptoms made a minimal contribution. By including executive functioning in their model, they conclude that inattentive-disorganized symptoms are the manifestation of executive functioning deficits among adults with ADHD. The strong negative association between inattention and Conscientiousness fits with this interpretation because prior personality research has demonstrated that Conscientiousness predicts functioning in key areas such as health outcomes and adaptive vs. maladaptive coping (see O'Cleirigh et al, 2007). Thus, low Conscientiousness and inattention may be the manifestation of poor executive functioning in the personalities of adults with ADHD and these difficulties are often the primary target of psychosocial treatment (e.g., Safren et al, 2010; Solanto et al, 2010).

Openness was significantly elevated in this sample compared to the normative group. However, as expected, this trait was not predicted by any ADHD symptom dimension (Table 1). One prior study in a general population sample showed a weak negative relationship between inattention and Openness (Parker et al, 2004). One interpretation is that, as a group, individuals with ADHD are more open to experience but that this trait does not vary with symptom severity.

Unexpectedly, we identified a relationship in this clinical sample not previously reported. In the context of the other associations, hyperactivity was positively associated with Conscientiousness. It is important to keep in mind, however, that even the most conscientious adult with ADHD in our sample reported Conscientiousness well below the normative mean. Among 15 adults who scored greater than one standard deviation above the ADHD sample mean on Conscientiousness, the mean score was 30.60 (3.40)—only at the 27th percentile and lower than the normative mean of 34.57. Thus, although hyperactivity positively predicted Conscientiousness in this clinical sample, this contribution is not likely to be clinically significant. However, given that the bivariate correlation (i.e. total association) between hyperactivity and Conscientiousness was closer to zero than the value of the direct association between these two factors when inattention was controlled, the current findings provide preliminary support that inattention may suppress a positive relationship between hyperactivity and Conscientiousness (see MacKinnon et al., [2000] for a description of suppressor variables). The current model suggests that the association of hyperactivity with Conscientiousness may involve meaningful pathways of opposite effect. Further work may help to identify non-pathological aspects of higher activity levels in some ADHD adults, such as higher levels of goal-directed activity.

Overall, our findings are consistent with other models of personality applied to ADHD. Using Gray’s (1987) Reinforcement Sensitivity framework, Mitchell (2010) found that the Behavioral Activation System (BAS)— sensitivity to cues of reward—positively predicted hyperactive-impulsive symptoms and BAS is most strongly related to higher Extraversion and lower Agreeableness (Mitchell et al, 2007). Our findings also map onto two of Nigg’s (2006, p. 185) three key personality traits theoretically related to ADHD: Approach (related to Extraversion, hyperactivity/impulsivity) and Effortful Control (related to inattention and Conscientiousness). Relationship to a third factor, anxiety-motivated Withdrawal (related to Neuroticism and impulsivity), is less clear because we found Neuroticism was related to inattention but not impulsivity. This may result from developmental changes in trait-symptom relationships. As hyperactive-impulsive symptoms decrease in intensity over time and inattentive symptoms continue to contribute to adaptive impairments and, possibly, internalizing comorbidity, Neuroticism may become more strongly associated with inattentive symptoms. This could be tested via longitudinal research designs.

The current study has limitations to be addressed by future investigations. We used the NEO-FFI and not the NEO-PI-R; thus, we were not able to examine facet-level scores or other types of analyses such as circumflex personality combinations. However, profiles suggesting lower levels of engagement (Ironson et al, 2008) were differentially associated with hyperactivity in this sample (Gloomy Pessimists N and Lethargic C-E- associated with lower hyperactivity; Maladaptive N associated with higher hyperactivity). These findings support maintaining all domains in personality analyses regardless of significance at the domain level and undertaking more comprehensive personality assessment using NEO-PI-R. Although we had two different sources for information on ADHD symptoms, we only assessed personality traits using self-report. A significant other’s report of traits and symptoms should also be included. Our sample was relatively high functioning and may not reflect the entire population of adults with ADHD—it is more similar to other clinically-referred samples than to children with ADHD followed into adulthood (Barkley et al, 2008). This sample was composed of adults being treated with medications for ADHD but still exhibiting residual symptoms sufficient to meet criteria for ADHD. Thus, results need to be replicated in more diverse samples of adults with ADHD with more varied treatment histories. In addition, our sample was relatively small in size compared to other investigations using SEM, and thus replication in larger clinical samples is also recommended. We only assessed these constructs at a single time point and were not able to test developmental hypotheses about personality in ADHD. Although we conceptualized ADHD symptoms as persistent, exogenous predictors of adult personality traits, cross-sectional investigations such as the current study cannot truly test the direction of causal relationships between psychopathology and personality, which may interact across development (Martel et al, 2010). Longitudinal investigations are needed. Finally, we chose to maintain hyperactivity and impulsivity as separate constructs in our model based on prior research and emerging theory on the structure of ADHD in adulthood. Future research should more carefully examine the relationship between these symptom domains with respect to method variance, given the interesting observation that these domains were more strongly correlated in the self-report measure compared to the clinician-report measure.

Conclusions

The current study replicated important links between ADHD symptoms and personality traits from the Five Factor model in a well-diagnosed clinical sample using structural equation modeling. Associations of inattention symptoms with lower Conscientiousness and higher Neuroticism were confirmed. Considering impulsivity and hyperactivity symptom dimensions separately, impulsivity was associated with lower Agreeableness while hyperactivity was associated with higher Extraversion. Developmental hypotheses about the changing nature and correlates of ADHD symptoms must be explored in future longitudinal work and may give insight into clinical issues such as the development of psychiatric comorbidity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christine Cooper-Vince for her assistance in manuscript preparation and Drs. Russell Barkley and John Mitchell for comments on earlier versions.

Source of Funding: Research supported by NIH Grants 5R01MH69812 and 1R03MH60940 to Steven A. Safren.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Error covariances omitted from depiction of baseline and final models for figure clarity. For final model, error covariances were: Conscientiousness with Neuroticism = −10.59, p<.05; with Extraversion = 7.87, p<.05; with Agreeableness = 6.49, p<.05. Extraversion with Neuroticism = −21.99, p<.001; with Agreeableness = 12.14, p<.01. Agreeableness with Neuroticism = −19.69, p<.001. Covariance of Conscientiousness error term with Openness was −7.14, p<.05.

Contributor Information

Laura E. Knouse, Email: lknouse@partners.org.

Lara Traeger, Email: ltraeger@partners.org.

Conall O’Cleirigh, Email: cocleirigh@partners.org.

Steven A. Safren, Email: ssafren@partners.org.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-Text Revision. (4 ed) Washington DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Gebring D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Deficient emotional self-regulation is a core component of ADHD. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. 2010;1:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. 3rd edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Braaten EB, Rosen LA. Emotional reactions in adults with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO Five-Factor Inventory (FFI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1992a. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1992b. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon WR, Kumar A, Mulani N. Offending estimates in covariance structure analysis: Comments on the causes of and solutions to Heywood cases. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas VI. Cognitive control processes in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Quay HC, Hogan AE, editors. Handbook of Disruptive Behavior Disorders. New York: Kluwer; 1998. pp. 105–138. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ. The ADHD Rating Scale: Normative data, reliability, and validity. University of Massachusetts Medical School. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Biometrics Research Department. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders, Patient edition. [Google Scholar]

- Glutting JJ, Youngstrom EA, Watkins MW. ADHD and college students: Exploratory and confirmatory structures with student and parent data. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:44–53. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, O'Cleirigh C, Weiss A, Schneiderman N, Costa PT. Personality and HIV disease progression: Role of NEO-PI-R openness, extraversion, and profiles of engagement. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:245–253. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816422fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C, Romanos J, Dempfle A, Heine M, Windemuth-Kieselbach C, Kruse A, Reif A, Walitza S, Romanos M, Strobel A, Brocke B, Schäfer H, Schmidtke A, Böning J, Lesch K-P. Co-morbidity of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with focus on personality traits and related disorders in a tertiary referral center. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0722-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Green JG, Adler LA, Barkley RA, Chatterji S, Faraone SV, Finkelman M, Greenhill L, Gruber MJ, Jewell M, Russo LJ, Sampson NA, Van Brunt DL. Structure and diagnosis of Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:1168–1178. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Sprich S, Cooper-Vince C, Safren SA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom profiles in medication-treated adults entering a psychosocial treatment program. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. 2009;1:1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooij JJS, Buitelaar JK, van den Oord EJ, Furer JW, Rijnders CA, Hodiamont PPG. Internal and external validity of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2004;35:517–827. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400337x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the Mediation, Confounding and Suppression Effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Nikolas M, Jernigan K, Friderici K, Nigg JT. Personality mediation of genetic effects on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:633–643. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney AA, Canu WH, Schneider HG. Distinct ADHD Symptom Clusters Differentially Associated With Personality Traits. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1087054711430842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, Miller SR, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Personality characteristics associated with persistent ADHD in late adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT. Behavioral approach in ADHD: Testing a motivational dysfunction hypothesis. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2010;13:609–617. doi: 10.1177/1087054709332409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Kimbrel NA, Hundt NE, Cobb AR, Nelson-Gray RO, Lootens CM. An analysis of reinforcement sensitivity theory and the five-factor model. European Journal of Personaltiy. 2007;21:869–887. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. What Causes ADHD? New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Blaskey LG, Huang-Pollock CL, John OP. ADHD symptoms and personality traits: Is ADHD an extreme personality trait? The ADHD Report. 2002a;10:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Casey BJ. An integrative theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:785–806. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, John OP, Blaskey LG, Huang-Pollock CL, Willicut EG, Hinshaw SP, Pennington B. Big Five dimensions and ADHD symptoms: Links between personality traits and clinical symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002b;83:451–469. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Weiss A, Costa PT. Conscientiousness predicts disease progression (CD4 number and viral load) in people living with HIV. Health Psychology. 2007;26:473–480. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H. Psychiatric interviews suitable for use in research with children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21:737–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JDA, Majeski SA, Collin VT. ADHD symptoms and personality: Relationships with the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:977–987. [Google Scholar]

- Ranseen JD, Campbell DA, Baer RA. NEO PI-R profiles of adults with attention deficit disorder. Assessment. 1998;5:19–24. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, Alderson RM, Kofler MJ, Sarver DE, Bolden J, Sims V. Working memory deficits in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): The contribution of central executive and subsystem processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:825–837. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Sprich S, Winett CL, Wilens T, Biederman J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2005;43:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Sprich S, Mimiaga MJ, Surman C, Knouse LE, Groves M, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. relaxation with educational support for medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms. JAMA. 2010;304:857–880. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV, Marks DJ, Wasserstein J, Mitchell K, Abikoff H, Alvir J, Kofman MD. Efficacy of metacognitive therapy for adult ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:958–968. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Span SA, Earleywine M, Strybel TZ. Confirming the factor structure of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms in adult, nonclinical samples. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2002;24:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Wilens T, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Ablon JS, Lapley KA. A double-blind cross-over comparison of methylphenidate and placebo in adults with childhood-onset attention deficit hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:434–443. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950180020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavro GM, Ettenhofer ML, Nigg JT. Executive functions and adaptive functioning in young adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13:324–334. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]