Abstract

Background

Visual information is a crucial aspect of medical knowledge. Building a comprehensive medical image base, in the spirit of the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS), would greatly benefit patient education and self-care. However, collection and annotation of such a large-scale image base is challenging.

Objective

To combine visual object detection techniques with medical ontology to automatically mine web photos and retrieve a large number of disease manifestation images with minimal manual labeling effort.

Methods

As a proof of concept, we first learnt five organ detectors on three detection scales for eyes, ears, lips, hands, and feet. Given a disease, we used information from the UMLS to select affected body parts, ran the pretrained organ detectors on web images, and combined the detection outputs to retrieve disease images.

Results

Compared with a supervised image retrieval approach that requires training images for every disease, our ontology-guided approach exploits shared visual information of body parts across diseases. In retrieving 2220 web images of 32 diseases, we reduced manual labeling effort to 15.6% while improving the average precision by 3.9% from 77.7% to 81.6%. For 40.6% of the diseases, we improved the precision by 10%.

Conclusions

The results confirm the concept that the web is a feasible source for automatic disease image retrieval for health image database construction. Our approach requires a small amount of manual effort to collect complex disease images, and to annotate them by standard medical ontology terms.

Keywords: Image Retrieval, Object Detection, Ontology

Introduction

Both textual and visual medical knowledge play crucial roles in healthcare and clinical applications. Doctors, caregivers, and patients need both natural language and images to illustrate diseases, medical conditions, and procedures. Scientists have constructed and reused a number of comprehensive textual knowledge bases in the medical domain, such as the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS).1 In comparison, fewer studies have attempted to systematically organize medical knowledge in a visual format. Many medical image bases concentrate on specific domains, such as lung CT images,2 cardiovascular MRI images,3 and human anatomy images.4 The scale of these databases is limited, largely because the image collection processes are manual and laborious. Also, they annotate images by natural language sentences, which introduce ambiguities in image retrieval. Last but not least, most existing image bases are not freely available.

Our eventual goal is to build a freely accessible, large-scale, patient-oriented health image base comprising images of human disease manifestations, organs, drugs and other medical entities. Unlike previous databases, we plan to build our image base in line with the UMLS structure and annotate images using terms from standard medical ontologies such as the FMA (Foundational Model of Anatomy),5 ICD9 (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision)6 and RxNorm.7 For each medical term, we seek to provide a set of high-quality images and create a rich and reusable information source for patient education, patient self-care and web-content illustration. In this paper, we focus on providing disease manifestation images. Since the image base is designed for consumers, we collect photographic images, which are a significant subset of all biomedical images. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first attempt to build a large-scale medical image base annotated with ontology terms.

The most challenging problem in building this image base is to collect a large number of credible images for millions of medical terms. The web is a readily available source: it is free; it contains billions of images; and is fast growing. But many web images are non-medical and need to be filtered. Although generic image retrieval engines such as Google can already retrieve reasonable images for text queries, they do not specialize in medical applications. For example, the top Google results for UMLS concepts ‘heart,’ ‘ear deformities, acquired’, and ‘ibuprofen’ do not only contain images of the heart organs, ear deformities and ibuprofen tablets, but also include other items such as cartoon symbols, paper snapshots, and molecular formulae.

In particular, image retrieval for disease terms is highly challenging, since disease manifestation images contain diverse objects and complex backgrounds. For example, positive examples of ‘hand, foot, and mouth disease’ may contain infected feet, hands, mouths, or tongues. These body parts are in different positions and sizes. In addition, more than one infected body part may appear in one single image. To collect disease images from the web, we clearly need a content-based image retrieval (CBIR) method that analyzes the image at the object level. This method should also require minimal manual effort, as the number of disease terms is large.

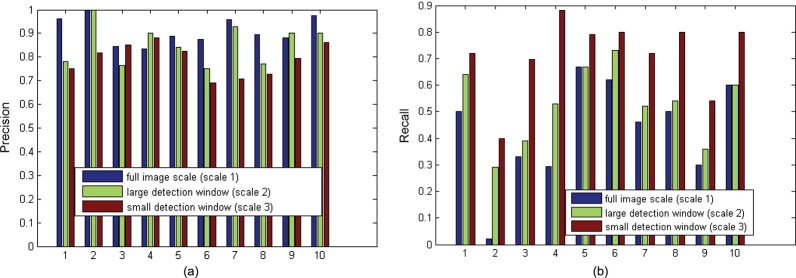

Figure 2.

(A) Trend for decreasing precision in finer scales. (B) Trend for increasing recall in finer scales.

Most CBIR systems apply machine learning approaches to bridge the semantic gap between image content and users’ interpretations.8 These approaches include supervised classification,9 10 similarity-based clustering,11 semi-supervised co-training,12 and active learning based on relevant feedback.13 A few methods incorporated additional information to improve retrieval precision. For example, Deserno et al14 exploited figure types and panel numbers to retrieve literature figures. Muller et al15 summarized the retrieval methods for integrating texts with image content. Simpson et al16 combined natural language and image processing to map regions in CT scans to concepts in RadLex ontology, which was automatically extracted from image captions. Deng et al17 used semantic prior knowledge to retrieve similar images. One particularly relevant method of reducing human effort in health image collection is the bootstrap image classification method.18 This approach uses one positive sample as the ‘seed’ to iteratively retrieve more positive images, and thus is appropriate for large-scale image collection. Although this approach effectively collects human organ and drug images, it has limited precision for disease images.18 Because web images are highly heterogeneous, our task requires supervision of the training data to ensure good precision. However, traditional supervised methods need a training image set for each disease, thus will not scale up when the number of disease terms is large.

To solve this scalability problem, we propose an ontology-guided organ detection method to collect disease manifestation images from the web. Based on observation, we assume that most disease manifestation images contain abnormal human body parts, such as eyes, ears, and hands, which show visible disease symptoms. Therefore, our approach uses the existence of these body parts to discriminate between images of disease and non-disease images. Instead of training a classifier for each disease, we pretrain a set of organ detectors, each of which detects one target organ. When retrieving images for a given disease, we extract the disease–organ semantic relationships from ontologies, and use the corresponding detectors to detect associated organs from web images.

Our method has two major advantages. First, we require much fewer training data than the standard supervised method, which trains a classifier for each disease, because we reuse organ detectors across diseases. For example, 428 diseases in the UMLS record eyes. Instead of training 428 classifiers, one for each disease, we train one detector for ‘eye’ and reuse it to classify 428 types of eye disease images. Second, our approach achieves high accuracy when disease images contain diverse manifestations of different organs, such as images of ‘hand, foot, and mouth disease.’ For each disease, we use prior knowledge of disease–organ associations as guidance to scan images at the object level.

Methods

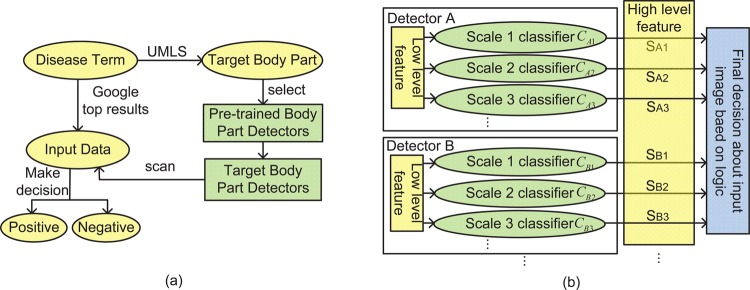

Our approach is based on a key observation that although the number of diseases is in the tens of thousands, most of them are shown on body parts, and the number of body parts is much smaller. This motivated us to develop image retrieval models by leveraging the disease–organ relationships from medical ontologies and sharing organ detectors among diseases. Figure 1A shows the workflow of this method. For a given disease term, we downloaded its top Google hits as the input, and selected the target disease manifestation images from the input following these steps: We first searched the UMLS for the organs affected by this disease. To detect these organs from the input, we scanned the images with the corresponding organ detectors, which had been pretrained using images independent of the disease. Finally, we combined the result of each individual organ detector to classify the input images into disease or non-disease.

Figure 1.

(A) Overview of our approach. We used the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) to determine the body part locations of disease manifestations and to select from a set of pretrained organ detectors to filter Google search results into relevant and irrelevant images. In comparison with a supervised method that would require labeled training examples for each disease, we achieved high precision in image retrieval with minimal human effort. (B) The structure of organ detectors. Our decision rule is based on multiple objects’ detectors using multiple scales. It is crucial to have multiple scales because some disease images have body parts occupying the entire frame, while others include a large portion of the background.

Discovering target body parts

For each disease, we found the affected body parts through the UMLS semantic network relationship of ‘has_finding_site.’ A single body part is typically associated with hundreds of diseases, and thus reusing common organ detectors across diseases can save a significant amount of manual labeling. Also, a disease can be displayed on multiple body parts: among the diseases that have the ‘finding site’ information in the UMLS, around 15% are located on more than one body part. For such complex diseases, we combined the organ detection results to boost the retrieval precision.

Within the UMLS, diseases may affect accessory body parts that are too detailed, such as the ‘oral mucous membrane structure,’ ‘upper eyelid’, and ‘lower eyelid.’ In images, symptoms on these body parts are often associated with larger organs, such as the mouth and the eye. Therefore, we systematically traced the UMLS ontology hierarchy following the ‘part_of’ relationship, and mapped these body parts to their upper-level terms until the preselected terms of the large organs were reached. For example, ‘oral mucous membrane structure’ is a part of the ‘mouth.’ Diseases affecting the ‘oral mucous membrane structure’ are then associated with the ‘mouth.’ In this paper, we preselected six organ terms (eye, lip, mouth, ear, hand, and foot) as the target body part, and performed image retrieval on associated diseases to prove the feasibility of our method.

Detecting target organs

We developed a general human organ detection method, and adapted it to specific targets by tuning the training data. We have trained five detectors for eye, ear, lip/mouth, hand and foot, and reused them in retrieving images of various diseases. These detectors are constructed in a generic way and can be easily extended to other body parts.

Object detection is a fundamental problem in computer vision. Approaches to object detection typically consist of two major components: feature extraction and model construction. Lowe19 developed the scale invariant feature transformation (SIFT) as the image patch descriptor. Dalal and Triggs20 proposed the histograms of oriented gradients (HOG) for human detection. These features have proved effective in object detection applications. In addition, Zhang et al21 constructed a bag-of-feature model to classify texture and object categories. Felzenszwalb et al22 developed a generic object detector with deformable part models to handle significant variations in object appearances.

Figure 1B shows the structure of our organ detector. Each detector i (i=A, B…) detects one target organ using multiple classifiers. Each classifier  scans the input image and searches for the target at detection scale j (j=1, 2…). For example, if detector A is an eye detector and contains three classifiers, then

scans the input image and searches for the target at detection scale j (j=1, 2…). For example, if detector A is an eye detector and contains three classifiers, then  decides if the full image is an eye,

decides if the full image is an eye,  scans the image with a detection window to search for small eyes, and

scans the image with a detection window to search for small eyes, and  searches for eyes of an even smaller size. The organ detection results

searches for eyes of an even smaller size. The organ detection results  are binary values and represent the existence of each organ

are binary values and represent the existence of each organ  at each detection scale {1, 2, …}. We then combined these results into high-level features, based on logic, to make final decisions about the input images. We found that the accuracies of our simpler detection system were comparable to that of Felzenszwalb et al.22

at each detection scale {1, 2, …}. We then combined these results into high-level features, based on logic, to make final decisions about the input images. We found that the accuracies of our simpler detection system were comparable to that of Felzenszwalb et al.22

Training organ detectors

For all classifiers in each organ detector, the training samples consisted of web images collected by Google. To collect positive examples, we searched the six body part names as the keywords and manually picked 200–300 images of the body part itself with little background. Most positive examples are not medically relevant, but contain different views of the body parts. To collect negative images, we summarized the categories of objects and backgrounds that often appear in the Google query results, such as paper snapshots, animals, and buildings. Negative examples were then collected by searching keywords such as ‘research paper,’ ‘dog,’ and ‘building.’ Five thousand images comprised the negative training set. We used the same negative examples for all the organ detectors.

We trained three standard soft margin support vector machine (SVM) classifiers for each organ detector to detect targets on three scales. In detector i,  was trained by full training images. Since

was trained by full training images. Since  and

and  search for targets with detection windows, they used positive samples that were resized to the window sizes, and randomly selected image patches of the window sizes from negative samples. We extracted the HOG features20 from training images. The HOG is reminiscent of the SIFT descriptor, but uses overlapping local contrast normalizations for improved performance.20 The window sizes of

search for targets with detection windows, they used positive samples that were resized to the window sizes, and randomly selected image patches of the window sizes from negative samples. We extracted the HOG features20 from training images. The HOG is reminiscent of the SIFT descriptor, but uses overlapping local contrast normalizations for improved performance.20 The window sizes of  and

and  were empirically chosen as 64×96 pixels and 32×48 for eye, lip/mouth, and hand detectors; and 96×64 and 48×32 for foot and ear detectors. By browsing 100 eye disease images, we found that images containing only very small target organs were usually false positives, therefore did not train classifiers at any smaller scale in order to maintain high retrieval precision.

were empirically chosen as 64×96 pixels and 32×48 for eye, lip/mouth, and hand detectors; and 96×64 and 48×32 for foot and ear detectors. By browsing 100 eye disease images, we found that images containing only very small target organs were usually false positives, therefore did not train classifiers at any smaller scale in order to maintain high retrieval precision.

Combining detections for disease image classification

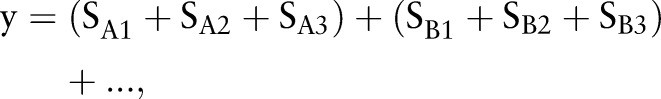

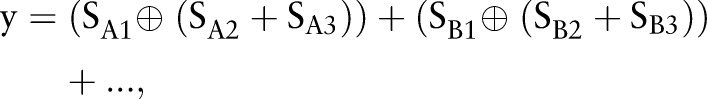

We finally used the organ detection results that represent the existence of affected organs as high-level features to classify the input images into disease or non-disease categories. Ideally, if all the classifiers behave in the same way and are independent, the high-level combined feature might look like:

|

1 |

where + is the ‘or’ operation between binary values.

However, we found that such a simple combination had problems. If the whole image itself is the target body part, it is unlikely to contain the same target at smaller scales. If a body part is detected at both the whole-image level and the finer scales, the image is often a false positive. This may be partly due to the incompleteness of the training samples or the challenge of detection of small-scale objects. Rule (1) ignores this problem and concludes that the result is positive if the classifiers at all three scales are positive. As precision is more important for our retrieval problem, we used the exclusive ‘or’ operation to set the decisions in such cases as negative, even though the recall might be decreased.

Our final decision rule was as follows:

|

2 |

where ⊕ is the ‘exclusive or’ and + is the ‘or’ operation between binary values. Comparison of the truth of (1) and (2) shows that the two equations make different decisions only when the detection results are positive at both the whole-image level and the finer levels, and then decision rule (2) is more desirable.

Results

We evaluated the proposed ontology-guided disease image retrieval method for two kinds of image sets: (1) images of multiple diseases that are located on the same body part, and (2) images of diseases that are located on more than one body part, in experiments A and B, respectively. All the test images were top Google search results for the given disease term. We excluded those images with either widths or heights smaller than 128 to ensure image quality. Also, to apply the organ detectors with the selected detection window sizes, we resized all test images such that both their widths and heights were between 128 and 256. For evaluation purposes, the test images were labeled by three human evaluators. Since performance depends on the ground-truth labeling, a majority vote was used among individual evaluators. The average agreement rate among the three evaluators was 92%.

Single-organ disease classification

Our method trained organ detectors by normal organ images. Since the test images can be quite different from the training images and much more diverse, we designed experiment A to evaluate the performance of our method by comparing the results with a supervised classification method. For each individual disease, the supervised method trained a soft margin SVM classifier using the actual disease images as training data, and extracted the same HOG features.

This experiment repeatedly compared our object detection-based method with the supervised classification method on 2000 test images in three groups. Each group contains 10 sets of eye, ear, and mouth/lip disease images, respectively. Our method trains a single object detector to classify the 10 test sets in each group. In contrast, the supervised method trains 10 different classifiers for each disease, thus requiring 10 times more human labeling effort. The methods compared their precisions, recalls and F1 measures. Precision is the most important criterion among the three, because our goal is to collect data for a health image base, and we are more interested in the credibility than the completeness of the images. Table 1 compares the performance for eye disease images. The average positive percentage of the 10 Google test image sets is 52.2%. After using our method, the average positive percentage of the retrieved images was 79.1%. For 9 out of 10 test sets, our method achieved precision of between 70% and 90%. The precisions, recalls and F1 measures of our method were comparable (p>0.1) to those of the supervised method for all the 10 test sets, even though our method only needs one tenth of the manual labeling effort, by reusing the organ detector across 10 diseases. In practice, our method will be able to reuse the eye detector for far more than 10 eye diseases and further reduce human effort.

Table 1.

Comparison of the performance of 10 eye disease image test sets

| Google test image sets: eye disease images | Object detection based method | Supervised classification method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease CUI | Disease term | Positive percentage (%) | Precision | Recall | F1 | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| C0009363 | Coloboma | 50 | 0.750 | 0.720 | 0.735 | 0.707 | 0.746 | 0.726 |

| C0013261 | Duane retraction syndrome | 45 | 0.818 | 0.400 | 0.537 | 0.779 | 0.652 | 0.710 |

| C0014236 | Endophthalmitis | 66 | 0.852 | 0.697 | 0.767 | 0.817 | 0.867 | 0.841 |

| C0015397 | Disorder of the eye | 63 | 0.882 | 0.882 | 0.882 | 0.683 | 0.700 | 0.692 |

| C0015401 | Eye foreign bodies | 41 | 0.826 | 0.792 | 0.809 | 0.648 | 0.687 | 0.667 |

| C0015402 | Eye hemorrhage | 45 | 0.692 | 0.800 | 0.742 | 0.772 | 0.821 | 0.796 |

| C0015404 | Bacterial eye infections | 50 | 0.706 | 0.720 | 0.713 | 0.807 | 0.864 | 0.834 |

| C0017601 | Glaucoma | 50 | 0.727 | 0.800 | 0.762 | 0.821 | 0.827 | 0.824 |

| C0025210 | Ocular melanosis | 50 | 0.794 | 0.540 | 0.643 | 0.723 | 0.689 | 0.706 |

| C0086543 | Cataract | 62 | 0.862 | 0.806 | 0.833 | 0.862 | 0.913 | 0.887 |

| Average | 52.2 | 0.791 | 0.716 | 0.742 | 0.762 | 0.777 | 0.768 | |

CUI, concept unique identifier.

Also, we observed that the object detectors at smaller detection scales tend to introduce more false-positive results. For eye disease image retrieval, a finer detection scale yields decreasing precision in 8 out of 10 test sets (figure 2A) and increasing recall in all test sets (figure 2B). The second test set of Duane retraction syndrome images has the lowest recall in all detection scales. One possible reason is that many positive images in this set contain eyes smaller than our detection window scales in order to illustrate the eye movement disorder. Adding organ detectors at smaller scales may increase the recall, but may also introduce many false positives. Since precision is of more importance, we stopped the object detection at the third detection scale.

Tables 2 and 3 show the results for ear and mouth/lip disease images. Our method achieved average precisions of 80.7% and 84.2%, while the baselines of test set quality were 43.4% and 47.5%, respectively. The three evaluation criteria in table 2 are similar between the two methods (p>0.1), and the average precision of our method for ear disease retrieval was higher than that of the supervised method. In table 3, our method achieved around 6% average higher precision than the supervised method (p=0.15), at the cost of lower recall. One possible reason is that the body parts in some mouth disease images from the test sets are at very different angles and considerably deformed.

Table 2.

Comparison of the performance of 10 ear disease image test sets

| Google test image sets: ear disease images | Object detection based method | Supervised classification method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease CUI | Disease term | Positive percentage | Precision | Recall | F1 | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| C0008373 | Cholesteatoma | 0.640 | 0.794 | 0.818 | 0.806 | 0.881 | 0.953 | 0.915 |

| C0013446 | Acquired ear deformity | 0.580 | 1.000 | 0.828 | 0.906 | 0.819 | 0.863 | 0.840 |

| C0013449 | Ear neoplasms | 0.340 | 0.875 | 0.412 | 0.560 | 0.733 | 0.567 | 0.639 |

| C0029877 | Ear inflammation | 0.450 | 0.921 | 0.778 | 0.843 | 0.822 | 0.804 | 0.813 |

| C0154258 | Gouty tophi of the ear | 0.290 | 0.792 | 0.655 | 0.717 | 0.614 | 0.470 | 0.532 |

| C0347354 | Benign neoplasm of the ear | 0.300 | 0.571 | 0.533 | 0.552 | 0.820 | 0.497 | 0.619 |

| C0423576 | Irritation of the ear | 0.360 | 0.733 | 0.611 | 0.667 | 0.933 | 0.607 | 0.735 |

| C0521833 | Bacterial ear infection | 0.340 | 0.786 | 0.647 | 0.710 | 0.820 | 0.670 | 0.737 |

| C0729545 | Fungal ear infection | 0.460 | 0.800 | 0.696 | 0.744 | 0.728 | 0.864 | 0.791 |

| C2350059 | Cancer of the ear | 0.580 | 0.800 | 0.414 | 0.545 | 0.797 | 0.699 | 0.736 |

| Average | 0.434 | 0.807 | 0.639 | 0.705 | 0.797 | 0.699 | 0.736 | |

Table 3.

Comparison of the performance of 10 mouth/lip disease image test sets

| Google test image sets: mouth/lip disease images | Object detection based method | Supervised classification method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease CUI | Disease term | Positive percentage | Precision | Recall | F1 | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| C0007971 | Cheilitis | 0.540 | 0.846 | 0.667 | 0.746 | 0.828 | 0.893 | 0.859 |

| C0019345 | Herpes labialis | 0.530 | 0.900 | 0.486 | 0.632 | 0.817 | 0.953 | 0.880 |

| C0023761 | Lip neoplasms | 0.400 | 0.909 | 0.500 | 0.645 | 0.607 | 0.553 | 0.579 |

| C0149637 | Carcinoma of the lip | 0.460 | 0.952 | 0.435 | 0.597 | 0.819 | 0.906 | 0.860 |

| C0153932 | Benign neoplasm of the lip | 0.300 | 0.625 | 0.333 | 0.435 | 0.833 | 0.713 | 0.769 |

| C0158670 | Congenital fistula of the lip | 0.380 | 0.700 | 0.368 | 0.483 | 0.693 | 0.800 | 0.743 |

| C0221264 | Cheilosis | 0.520 | 0.750 | 0.577 | 0.652 | 0.813 | 0.867 | 0.839 |

| C0267022 | Cellulitis of the lip | 0.400 | 0.923 | 0.600 | 0.727 | 0.810 | 0.917 | 0.860 |

| C0267025 | Contact cheilitis | 0.700 | 0.950 | 0.543 | 0.691 | 0.849 | 0.943 | 0.894 |

| C0267032 | Granuloma of the lip | 0.520 | 0.867 | 0.500 | 0.634 | 0.721 | 0.865 | 0.786 |

| Average | 0.475 | 0.842 | 0.501 | 0.624 | 0.779 | 0.841 | 0.807 | |

Multiple-organ disease classification

Experiment B evaluated the performance of our method on 220 images of two diseases that are located on multiple organs. Table 4 shows that the precision of the proposed method on both test sets was >80%. Compared with the supervised method, our method improved precision by more than 10% in these two cases. Since the proposed method is guided by the semantic information of body part location, it can detect various kinds of positive images, whereas the supervised method does not make use of the high-level features that have greater semantic meaning.

Table 4.

Comparison of the performance of two complex disease image test sets

| Disease CUI | C0018572 | C0339085 |

|---|---|---|

| Disease term | Hand, foot and mouth disease | Ascher's syndrome |

| Positive percentage | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| Disease locations | C0222224 Skin structure of hand C0222289 Skin structure of foot C0026639 Oral mucous membrane structure |

C0023759 Lip structure C0015426 Eyelid structure |

| Detectors | Hand, foot and mouth/lip | Mouth/lip and eye |

| Precision | ||

| Object detection based | 0.8333 | 0.8889 |

| Supervised classification | 0.6944 | 0.7857 |

| Recall | ||

| Object detection based | 0.7143 | 0.8571 |

| Supervised classification | 0.7753 | 0.9429 |

| F1 | ||

| Object detection based | 0.7692 | 0.8727 |

| Supervised classification | 0.7326 | 0.8571 |

For hand, foot, and mouth disease, 42.9%, 28.6%, and 37.1% of the positive images in the test set contained a hand, foot, and mouth, respectively. A few positive images contained two or three body parts at the same time. The hand, foot, and lip/mouth detectors contributed to finding 28.6%, 14.3%, and 28.6% of the total positive images. For Ascher's syndrome, 67.9% and 32.1% positive test images contained lip and eye, respectively. The corresponding mouth/lip and eye detectors found 57.1% and 28.6% positive images, respectively, from the whole test sets.

In summary, we trained five organ detectors and reused them to filter 2220 web images of 32 different diseases in two experiments. Compared with the supervised approach that require training 32 classifiers for each of the diseases, we reduce the labeling efforts to 15.6%. The average retrieval precision of our method on all the 32 datasets was 81.6%, an improvement of 3.9% compared with the supervised method. For 13 out of 32 disease datasets, we improved the retrieval precision by 10%.

Discussion

With the aim of achieving large-scale medical image retrieval, we compared the proposed ontology-guided approach with standard supervised classification. We showed that the proposed method achieves a precision comparable to that of the supervised method while saving manual labeling efforts by an order of magnitude. The results also illustrated that our method has limitations in low recall values on some test sets and in decreasing precision when the detection scale becomes smaller. To improve the recall, we need more robust algorithms and better data to train the organ detectors. For the limitation of decreasing precision, we plan to build a two-layer learning model, in which the first layer classifiers detect target objects at different scales and the second layer classifier learns the weights to combine results from the first layer and make final decisions.

The scale of our experiments is limited owing to the intensive manual labeling work required for training data and evaluation purposes. Our experiments are based on five organ detectors. In the future, we plan to train more organ detectors and apply the method to handle more diseases. We also found that a few organs, such as skin, muscle, and veins, do not appear as concrete objects in images. Our method based on object detection is insufficient for diseases on these organs. In future work, we plan to add texture pattern recognition to further improve the retrieving precision and cover a wider range of diseases.

Our approach also depends on disease–organ relationships in the UMLS, and assumes that the appearance of related organs determines if the image is disease-related or not disease-related. Although the assumption is true for many cases as we have shown, a small number of false-positive samples retrieved by our method are still non-disease images (only contain normal organs), or images of a different disease. Another limitation of this assumption is that the value of ‘has_finding_site’ relationship in the UMLS is incomplete. Among 74 785 disease concepts of semantic-type ‘disease or syndrome,’ ‘neoplastic process,’ ‘acquired abnormality’, and ‘congenital abnormality,’ 44.1% have values in ‘has_finding_site.’ For disease terms that have no body-site information, we plan to extend our approach by scanning the web images with all organ detectors. In this way, the ‘has_finding_site’ relationship in the UMLS can be enriched by mining web images.

Conclusion

In this work, we developed an ontology-guided disease image retrieval method based on body-part detection towards mining web images to build a large-scale health image base for consumers. Compared with standard supervised classification, the proposed method improves the retrieval precision of complex disease images by incorporating semantic information from medical ontologies. In addition, our method significantly reduces manual labeling efforts by reusing a set of pretrained organ detectors. The resulting health image database is annotated using terms from standard medical ontologies and will create a rich source of information for multiple descriptive and educational purposes. Although the scale of our study is limited, it proves the concept that the web is a feasible source for automatic health image retrieval, and it only requires a small amount of manual effort to collect and annotate complex disease images. In future work, we plan to improve the accuracy of organ detectors and ontology-based classification, and extend our approach to handle a wider range of diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: RX conceived and started the project of building a consumer-based image base. YC and RX designed and developed the proposed image retrieval method. YC and XR implemented the method and performed experiments. YC, XR, GZ and RX contributed to formulating the question of building the health image base and prepared the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Clinic CTSA. Grant UL1 RR024989.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lindberg D, Humphreys B, McCray A. The unified medical language system. Methods Inf Med 1993;32:281–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armato S, III, McLennan G, McNitt-Gray M, et al. Lung image database consortium: developing a resource for the medical imaging research community. Radiology 2004;232:739–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keator D, Grethe J, Marcus D, et al. A national human neuroimaging collaboratory enabled by the biomedical informatics research network (birn). IEEE Trans Inf Tech in Biomed 2008;12:162–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A.D.A.M. http://www.adam.com/ (accessed Sept 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosse C, Mejino J. A reference ontology for bioinformatics: the foundational model of anatomy. J Biomed Inform 2003;36:478–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ICD-9-CM: international classification of diseases, 9th revision; clinical modification, 6th edition, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu S, Wei M, Moore R, et al. Rxnorm: prescription for electronic drug information exchange. IT Professional 2005;7:17–23 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datta R, Joshi D, Li J, et al. Image retrieval: Ideas, influences, and trends of the new age. ACM Comput Surv 2008;40:1–60 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapelle O, Haffner P, Vapnik VH. Support vector machines for histogram-based image classification. IEEE Trans Neural Networks 1999;10:1055–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panda N, Chang EY. Efficient top-k hyperplane query processing for multimedia information retrieval. ACM International Conference of Multimedia; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. 2006;317–26 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Wang JZ. Real-time computerized annotation of pictures. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2008;30:985–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng H, Shi R, Chua TS. A bootstrapping framework for annotating and retrieving www images. ACM International Conference of Multimedia; New York, NY, USA. 2004;960–7 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong S, Chang E. Support vector machine active learning for image retrieval. The Ninth ACM International Conference on Multimedia; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 2001;107–18 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deserno TM, Antani S, Long RL. Content-based image retrieval for scientific literature access. Methods Inf Med 2009;48:371–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muller H, Herrera A, Kalpathy–Cramer J, et al. Overview of the ImageCLEF 2012 medical image retrieval and classification tasks. CLEF 2012 Evaluation Labs and Workshop, Online Working Notes; Rome, Italy, 17–20 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson MS, You D, Rahman MM, et al. Towards the creation of a visual ontology of biomedical imaging entities. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings; Chicago, Illinois, USA. 2012;866–75 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng J, Berg A, Fei-Fei L. Hierarchical semantic indexing for large scale image retrieval. IEEE Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Colorado Springs, CO, USA.2011;785–92 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Zhang G, Xu R. Semi-supervised image classification for automatic construction of a health image library. ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium; Miami, Florida, USA. 2012;111–20 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe D. Object recognition from local scale-invariant features. International Conference on Computer Vision; Kerkyra, Corfu, Greece. 1999; 1150–7 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalal N, Triggs B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. IEEE Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); Miami, FL, USA. 2009;1:886–93 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Marszalek M, Lazebnik S, et al. Local features and kernels for classification of texture and object categories: a comprehensive study. Int J Computer Vision 2007;73:213–38 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felzenszwalb P, Girshick R, McAllester D, et al. Object detection with discriminatively trained part based models. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2010;32:1627–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]