Abstract

Objective

As large-scale medical imaging studies are becoming more common, there is an increasing reliance on automated software to extract quantitative information from these images. As the size of the cohorts keeps increasing with large studies, there is a also a need for tools that allow results from automated image processing and analysis to be presented in a way that enables fast and efficient quality checking, tagging and reporting on cases in which automatic processing failed or was problematic.

Materials and methods

MilxXplore is an open source visualization platform, which provides an interface to navigate and explore imaging data in a web browser, giving the end user the opportunity to perform quality control and reporting in a user friendly, collaborative and efficient way.

Discussion

Compared to existing software solutions that often provide an overview of the results at the subject's level, MilxXplore pools the results of individual subjects and time points together, allowing easy and efficient navigation and browsing through the different acquisitions of a subject over time, and comparing the results against the rest of the population.

Conclusions

MilxXplore is fast, flexible and allows remote quality checks of processed imaging data, facilitating data sharing and collaboration across multiple locations, and can be easily integrated into a cloud computing pipeline. With the growing trend of open data and open science, such a tool will become increasingly important to share and publish results of imaging analysis.

Keywords: Image processing, Reporting

Background and significance

Large-scale imaging studies focusing on a particular disease have become a powerful investigation tool in medical research. They often include hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of subjects who are imaged using multiple imaging modalities and contrasts acquired over multiple time points. For example, the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)1 was one of the first large-scale imaging studies investigating Alzheimer's disease comprising 800 subjects imaged with MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) over several years at multiple time points. It was followed by the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Flagship study of Ageing (AIBL)2 in which close to 250 subjects were imaged with MRI and PET using an amyloid marker (PiB). Both studies were subsequently extended to increase the size of the cohort and the number of time points. Similar clinical studies of Alzheimer's were then initiated in Europe, Japan, Taiwan, Korea and China. Several other large-scale open access imaging studies are investigating neurological disorders such as Parkinsons3 (N=600), autism4 (N=1112) and fronto-temporal dementia5 (N=240), looking at individuals with and without dementia across the adult life span6 7 (N=416), or looking at brain connectivity in healthy controls8 (N=1200). The availability of these large open source datasets has had a tremendous effect on the scientific outputs in the medical image analysis community, with ADNI, for example, reporting over 340 journal publications resulting from the use of their data.

With ever more data available to the research community arises the issues of analyzing and extracting quantitative information from each image to perform clinical and statistical analysis on the entire cohort. As a result, there has been a strong motivation in the medical image analysis community to develop integrated software or processing pipelines to analyze large datasets, and extract clinically relevant measurements, such as the volume or thickness of specific structures in the brain or the retention of PET tracers in such regions.

A great challenge for the medical imaging community developing such software is to communicate the results of the image analysis to the clinical research community, which relies on these results to support their own research. Most image analysis software generate new images (such as an image registered to an atlas or the labeling of anatomical structures), and some quantitative metrics (often in text format such as volume, thickness, etc) for whole organs, areas within those organs, or even for each pixel. Clinicians are often overwhelmed by the complexity of the image processing algorithms and can use the results without any clear understanding of the methods used or the ability to check intermediate processing steps. This often leads to blind acceptance of the results, or tedious and time consuming visual inspection of image registration or segmentation for example, a solution only feasible for small cohorts of subjects or for obvious outliers. As the size of the cohorts keeps increasing, there is a need for tools allowing the presentation of results (as well as automated quality controls) from image processing and analysis in a way that enables fast and efficient quality check, tagging cases in which automatic processing failed, customizing options, or performing some manual intervention if needed.

The commonly used neuroimaging software, as described in table 1, has non-existent or limited reviewing capabilities. It also has a rigid framework, which limits customization of the reports for specific needs or cross-comparison. To address these shortcomings, reporting software should have the following requirements: quick, easy and efficient reviewing of various image processing actions; summary of user-defined metrics (usually provided by the software or extracted from the data); web-based interface to add user-generated reports that can be used for collaborative work; adaptable to various imaging software.

Table 1.

Review of existing software's capability for review of processed data

| Generates reports | Reporting at various stages of the processing pipeline | Subject/population based | Report format | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer | No | Manual review of individual images and meshes | NA | NA |

| NeuroQuant | Yes | Limited to a fixed reporting template | Population based: graphs show selected metric of the subject with regard to a fixed reference population | |

| FSL | Yes | Application dependant | Subject based: the report only shows the subject | html |

| SPM | Yes | Manual review of individual images | Population based: glass brain show t values with regard to the reference population |

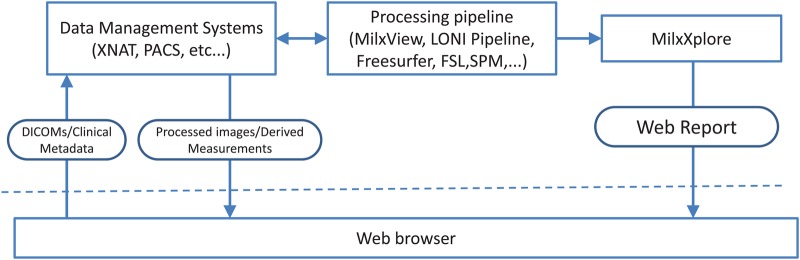

With the growing availability of supercomputers and cloud computing interfaces, some of these software solutions are now starting to be available through web portals, facilitating and accelerating the processing for the end user without the need to maintain a large computing facility on site. A typical set-up involves a data store to manage/share/serve the data (PACS, XNAT,9 etc.…) remotely. A processing pipeline (MilxView,10 Freesurfer,11 LONI Pipeline,12 etc.…) will then query the data store to access a dataset, process the data, and send back the results to the end user, typically through the data store (figure 1). Quality control in such a set-up becomes even more problematic as a large volume of data needs to be downloaded for review, and intermediate results might not be necessarily saved, or made available to the end user. A web-based solution would alleviate some of the issues with quality control for remotely processed data.

Figure 1.

Typical processing pipeline for web-based image processing of large clinical imaging studies and MilxXplore integration. Access the article online to view this figure in colour.

With these requirements in mind, we have developed MilxXplore (pronounced ‘milx explore’), a tool designed to explore the results of a processing pipeline via a web browser in a fast, simple and intuitive way. MilxXplore gives the option to assess the results qualitatively and quantitatively, and has support for recording quality control checks and marking images for reprocessing. MilxXplore is designed to be called at the end of the processing pipeline (figure 1), to summarize and extract relevant information from the generated results (images/meshes/spreadsheets) by thumbnails, tables and graphs. The resulting report is lightweight and can be accessed remotely by a web browser without the need to download a large quantity of data.

Objective

The aim of MilxXplore is to simplify the representation of data, and to aggregate the results for fast and user-friendly exploration of imaging data. In simple analysis, three-dimensional (3D) volumes are converted to two-dimensional (2D) thumbnails of representative slices, segmentations are overlayed on the source images, 3D meshes are summarized by 2D projections, quantitative measurements are presented in tables and graphs showing the changes over time, and when possible compared to a normative metrics from a control population.

In this paper we present an overview of MilxXplore, discuss the design choices, and will show how MilxXplore can be integrated in the workflow of an imaging study. Example reports showcasing the capabilities of MilxXplore on a subset of the AIBL study and the open access series of imaging studies (OASIS)6 7 can be accessed at http://milxview.csiro.au/MilxXplore.

Materials and methods

MilxXplore is a PHP (http://php.net) web application implemented within the Symfony (http://symfony.com) framework. The Symfony framework provides a core set of libraries that are easily extended and utilized for a diverse set of applications including content management.

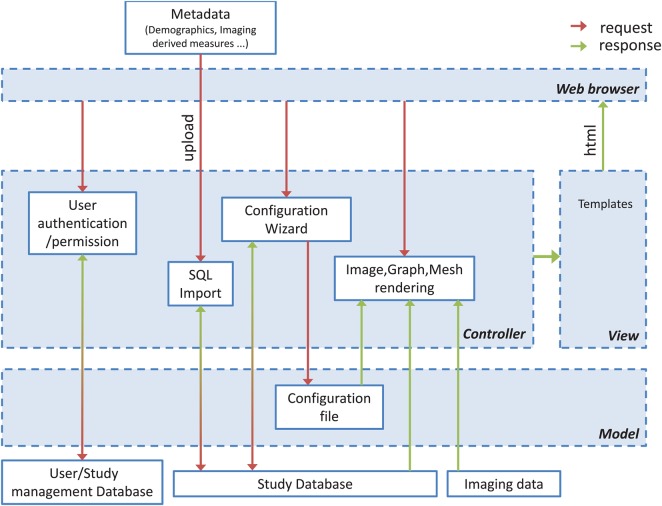

A general overview of MilxXplore is provided in figure 2. The MilxXplore core libraries generate all the 2D thumbnails, multi-slice extraction and various fused/augmented/rendered visualization from high-dimensional volumes (typically three dimensions), the generation of graphs (using the statistical package R), and the inclusion of these graphs in the resulting html pages.

Figure 2.

MilxXplore follows a model–view–controller architecture to separate the representation of the data from the user's interaction with them. All user interactions are handled by the controller. The controller interacts with the model and the view, to render the pages displayed to the user. Access the article online to view this figure in colour.

The reporting utilized by each experiment in a study is generated from a user customizable configuration file. This file describes the type of visualization and graphs required, the metrics to be displayed on the report and the images to be displayed. A configuration wizard provides an intuitive interface to generate the configuration file, and provides standard default options tailored to the software used to process the data (the current release provides pre-configured templates for MilxView and FreeSurfer).

A database (currently populated from csv formatted text files) contains all the demographic information of the subjects (age, diagnosis, sex, etc.…), the metrics that have been extracted by the imaging analysis pipeline (volume, thickness, PET retention, etc.…) and other relevant information/metrics (scores from neuropsychological evaluation, genotyping, etc.…), a subject CaseID, and the time points. The information is queried by PHP from the database to populate tables and graphs dynamically and generate the html pages, allowing dynamic web reporting.

Results

Study/experiment management and security

User authentication is handled by the Symfony framework: ‘Symfony's security system works by determining who a user is (ie, authentication) and then checking to see if that user should have access to a specific resource or URL’. It would be possible, however, to extend this and utilize external authentication provided by other data management software.

Using the obtained authentication, MilxXplore then provides access controls for each ‘experiment’ in a study. This allows the sharing of specific study or experiment with a user or defining studies as being private or public. Users can also be given privileges, such as validating (usually some type of quality control) the data or editing the database. For increased safety, information about each study (demographics, statistics) is kept in separate databases using SQLite, so that there is never one database containing all the information about all studies. Security can be enhanced by enabling SSL encryption on all traffic. As with all remote applications, there remains a security risk when sharing data on the internet, and it is recommended to use MilxXplore on a (virtual) private network.

When setting up a new study, the user starts by adding a new study/experiment, setting up permissions and adding a summary/description of the study. There are multiple levels of permission defined for each study:

Private: access is restricted to the owner.

ProtectedPlus: access is restricted to the owner and authorized users (not publically listed or searchable).

Protected: similar to ProtectedPlus, but the experiment summary is publicly available so that other users can request access.

Public: accessible to all users.

The permissions are defined when the study is created, but can be changed at a later time.

Experiment set-up

After setting up a new experiment within a study, the owner uploads a demographic file (currently a csv), which gives information about the subjects (such as age, sex, years of education, diagnosis, etc.…) and one or more statistics file (such as volumes in various regions of interest, cortical thickness, PET retention, etc.…), which was generated by the processing pipeline. These files are then added to the database. The next step is to configure the rendering of the study, which is done through a configuration wizard. The wizard will guide the users through the various steps of configuring the image and mesh rendering, parameters of the graphs (with the axis defined by drop-down boxes, populated using the database entries), and other information to be displayed on the summary page and subject page. At the end of the wizard, the user can render a test page for a given subject to verify that all the parameters are correct, and once satisfied with the results, can run the rendering on the entire study. The rendering is run in the background, and the user can start browsing the website and view the results as they are being processed.

One important aspect of medical image visualization is that the rendering profiles needs to be customized for each modality. For example, a grayscale color map is most suitable for most MRI acquisition, whereas a color map is more suitable for PET images, and a color map with a discrete set of non-sequential colors will be more suitable to display a parcellation. Also, the intensity of an MR image is not quantitative, and therefore its intensity needs to be rescaled for display, whereas PET images, after normalization (eg, normalized uptake to a reference region), are quantitative and do not require any additional rescaling.

Defining the best options for image rendering can be quite time consuming, and the approach used by MilxXplore is to used predefined rendering profiles, which can be selected by the user through the configuration wizard. These rendering profiles have been preset based on previous experience on the best visualization for each modality. For more advanced users, these profiles can be easily extended and added as an additional template type (using a text editor). This leaves the user to select the rendering profile, image overlay if required, and text to be overlaid on the rendered screenshots in the configuration wizard. The text can be a simple string or any field queried from the database for that subject. Reference masks (or label images) can also be declared in the configuration, and are then used to perform the appropriate normalization (such as trimming the top N% of the intensity within a mask, which is the most robust way to normalize the intensity of a brain T1-weighted MRI using the white matter mask).

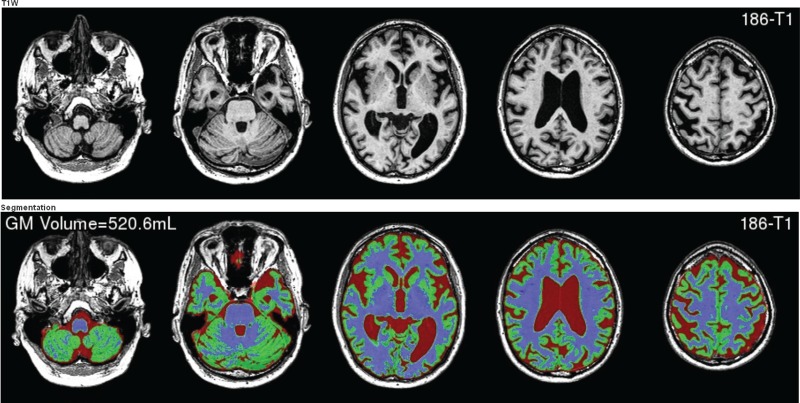

This configuration means that most use cases can be achieved and applied to the whole experiment. The example presented in figure 3 shows a T1-weighted image, along with its corresponding whole-brain segmentation, with the total gray matter volume overlaid on the display.

Figure 3.

Example display of the T1-weighted MRI and its corresponding whole-brain segmentation and the total gray matter volume overlaid on the image. These images were automatically generated by MilxXplore. Access the article online to view this figure in colour.

Data exploration

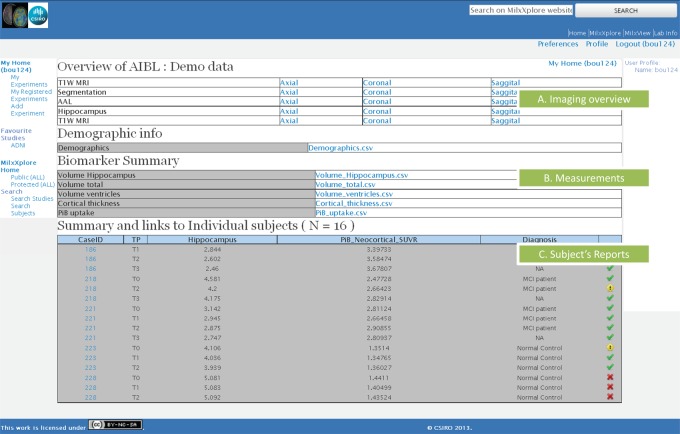

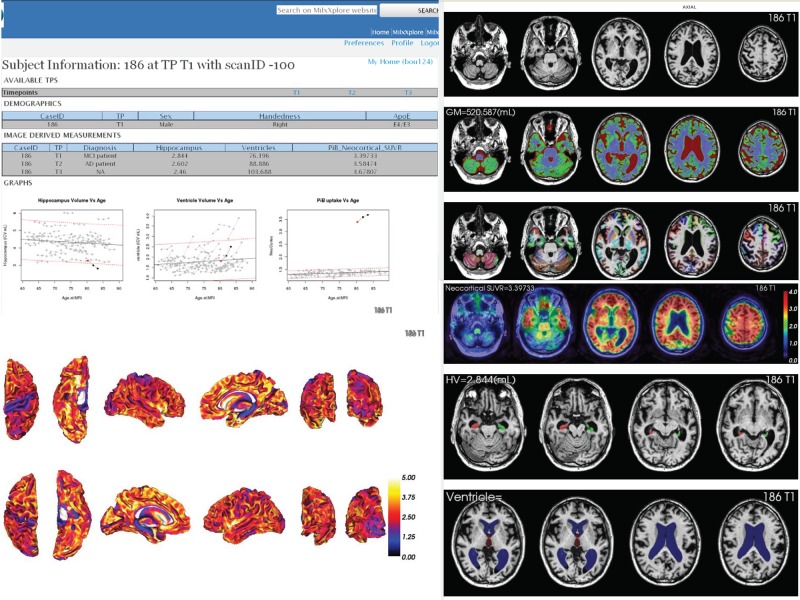

Figure 4 shows the experiment page of MilxXplore, which contains links to various imaging reports (figure 4A), with each report showing the thumbnails of all subjects corresponding to a specific representation (eg, showing the hippocampus segmentations of the entire population). Below (figure 4B) is a link to the extracted measurements in a text file. Then (figure 4C) is a link to all the subject's reports, each containing all the measurements and images of all acquisitions for the subject of interest (figure 5). The tables contain the selected measures for all time points so that the end user can quickly assess the evolution of the subject over time. Links at the top of the page allows the navigation between the reports at each time point. The graphs also represent the evolution of the metrics over time, and against the selected population of reference. Below the graphs, representative 2D views in axial, sagittal and coronal views of the 3D volumes are included. These can be either simple 2D views to show a particular MRI or PET image, or overlays of one image on the top of another to illustrate, for example, the accuracy of a registration or segmentation of a region of interest (figure 5). By clicking on one image, the user can navigate between the images representing the same information in all time points. This is particularly useful to check the changes visually over time, such as brain atrophy over time, and changes in PET retention.

Figure 4.

View of the experiment page of MilxXplore with: (A) the imaging overview where the user can access the images of all subjects for a given rendering/modality; (B) links to download the measurement spreadsheets; and (C) the link to the subject's report as well as relevant information as defined by the user. Access the article online to view this figure in colour.

Figure 5.

Subject's report showing the metrics of all time points in one web page (left) and representative slices of various image analysis steps (right), Showing the registration between positron emission tomography (PET) and MRI, with from top to bottom structural T1-weighted MRI, PiB PET image, PET overlaid on MRI, full brain MRI segmentation, MRI parcellation of various regions of interest. Access the article online to view this figure in colour.

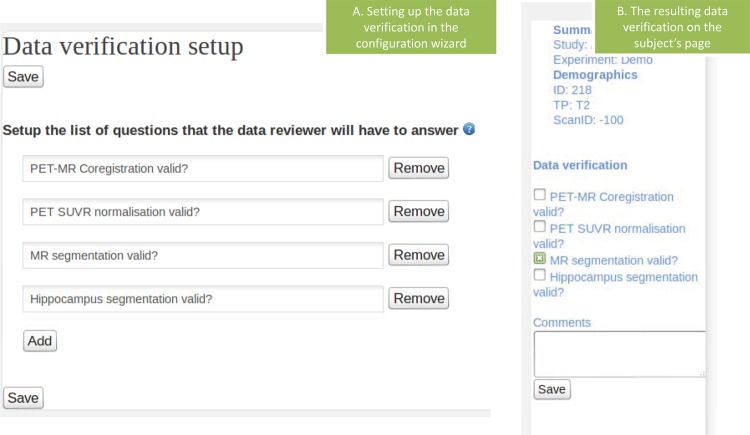

Data validation

A validation tab can be defined for each experiment (figure 6A) and then become available on each subject's page. This allows the end user to validate the analysis for each subject, or to report problems and mark the subject for re-analysis. The choice is then recorded in the database, and this can be used as a check before the analysis for this subject is externally published. An example of the validation tab is presented in figure 6. The results of the validation are then summarized on the study summary page in the form of small icons next to each subject ID (figure 4C).

Figure 6.

(A) The page used to define the questions which will be part of the manual validation and (B) the resulting validation form used to record quality checks on various image processing steps. Access the article online to view this figure in colour.

In addition to the manual validation, automated tests can be set up on the detect outliers based on the metrics provided in the statistics files, and stored in the database. The user can define an acceptable lower and upper bound on these metrics, and any case falling outside these bounds will tagged as an outlier.

Integration in the analysis workflow of an imaging study

Using XNAT as an example of data store, new images are first de-identified, uploaded by the clinical research sites to XNAT. At this stage, the processing pipeline can be automatically started and the MilxXplore study website is updated. An approved investigator can log on to the secured website, where he can see the entire cohort with the clinically relevant information. He can then access the reports of the new subjects that have been tagged as ‘unverified’ on the main page, and visually check the registration of the PET to the MRI, the segmentation of the brain, ventricles, and the hippocampus, or check that the regions used for intensity normalization of the PET images are properly defined. He can also navigate between time points to verify consistency of the registrations or segmentations over time. He can further investigate the subject's hippocampus volume as a function of age with respect to the control population, and recognize that its volume is close to the 95% CI line, suggesting accelerated atrophy. To inspect the hippocampus more closely he can download the 3D image and visualize it with a standard viewer. This could be confirmed by the clinical information on top of the page showing a low mini-mental state examination score for example. If he is satisfied with the image analysis he would validate the processed images using the side menu and also add a comment. The files are flagged as ‘verified’ and locked. On the main page he can download the measurements spreadsheet to study the correlation of the hippocampus with PiB retention.

Discussion

To illustrate further the need for a reporting tool, we looked at the three most commonly used free software packages for neuroimaging analysis: the statistical parametric mapping toolbox (SPM)13 for volumetric analysis and functional MRI studies, FreeSurfer for cortical thickness measurements, and FSL14 for volumetric analysis. Freesurfer does not offer any reporting capability, the user has to load all the meshes and results manually in the FreeSurfer viewer. A commercial software derived from FreeSurfer (NeuroQuant), provides a morphometric report for each subject in pdf format, containing representative screenshots of the segmented structures, overlaid on the MRI, and volume measurements of the hippocampus and the ventricles. An example of such a report can be found on NeuroQuant's website (http://www.cortechs.net/includes/getPDF.php?p=NeuroQuantAgeReport.pdf). One of the interesting features of such a report is the age-related atrophy reporting, which includes a graph showing the normal volume for the population, with lines representing the 50% and 95% percentiles. This provides a good overview of the overall status of the subject of interest in the general population and gives some extra mean to perform quality control. There are, however, several limitations to this approach as the output cannot be customized, and it can only be run with the NeuroQuant processing pipeline; there is a single pdf report per subject, which can make it tedious to review the results; it is limited to MRI morphometry (it cannot include other modalities such as PET imaging); it does not include information about longitudinal changes; the reference population is predefined, and cannot be changed.

For population analysis, SPM generates a pdf file for each subject showing the regions of significant difference on a ‘glass’ brain, and p values for the identified clusters. This approach allows the user quickly to visualize the regions of importance on a template. It does not, however, give the user the ability to check easily the accuracy of the different steps that were accomplished before the final result, such as the normalization to the template, or the segmentation of the gray matter for volumetric analysis. The user has to load and visualize individual files that have been saved during processing. The generation of one pdf file per subject can also be cumbersome and time consuming to review.

FSL offers automatic reporting, generating an html page showing the results of each of the steps involved in the analysis with one or multiple slices of the image of interest in axial, coronal and sagittal views. For example, running the ‘structural image evaluation, using normalization, of atrophy’ tool (SIENA), will generate an html page showing the results of the following tools: the brain extraction tool with the extracted brain mask overlaid on the MRI of the brain; FMRIB's linear image registration tool with an animation alternating between the baseline and follow-up MRI after co-registration; FMRIB's automated segmentation tool showing the segmentation overlaid on the MRI; SIENA showing the regions of atrophy. An example of such a report can be seen on the FSL website (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fslcourse/fsl_course_data/seg_struc/siena_problems/eg3/S2_080_ax_to_S2_121_ax_siena/report.html ). This approach, however, lacks the higher level of analysis (provided, for example, by NeuroQuant) giving no general overview of the metrics derived from the subject of interest with regard to the general population. This reporting is also part of the execution of the application, which means that it cannot easily be integrated into other applications.

Whereas the FSL tool generates a standard report per application, independent for each subject, MilxXplore is study based, which means that the results are driven by the population being analyzed. It includes tools to browse easily through the different acquisitions of a subject over time, allowing, for example, to show the atrophy on an MRI, the change in PET retention or the cortical thinning on a 3D mesh. The derived measurements are also used to build graphs, showing the evolution of these measures over time, and how they compare with the population of interest. Another important aspect of MilxXplore is adding a layer of flexibility so that it can be run on the results generated by most tools that write images in a format that MilxXplore can use, with minimal human intervention and customization. Even though MilxXplore has been presented in a neuroimaging context, it has been applied to other studies, including prostate cancer segmentation, musculoskeletal segmentation of the hip, shoulder, knees and spine,15 and even plant phenotyping with 3D representations of meshes of plants scanned over time.16 MilxXplore can also be easily extended to include more complicated visualization or analysis (eg, shape analysis, kinematic analysis, diffusion).

Limitations

MilxXplore has only been customized to a few studies using our processing pipeline in MilxView and FreeSurfer. We are planning to extend it to be used with the most commonly used neuroimaging software such as FSL and SPM.

A review of image processing quality using 2D thumbnails is usually sufficient to detect problems and estimate the quality of image registration, or whole-brain segmentation, but it is not always sufficient to see all the details of the segmentation of small structures, such as the hippocampus. In such cases, a 3D viewer embedded inside the webpage that allows slice by slice visualization and zooming may be more suitable (and is planned for future releases).

Even though MilxXplore is designed to work with any data, even clinical, it is limited to research applications, and is currently not suitable for or aimed at clinical applications.

Conclusion

As technology evolves, increasingly complex algorithms and pipelines with numerous parameters are employed in the analysis of imaging data. As the size of studies keep growing, so does the reliance on these automated methods to extract information from the images. There is a growing need for better tools to explore and validate data and to perform quality control. MilxXplore aims to fill the missing gap and provide transparent reporting and publishing of the results obtained from automatic data processing before quantitative numbers are extracted and used in large statistical analysis by clinicians or scientists not expert in computer science.

We have presented a new tool to allow the efficient investigation of the results of a processing pipeline. It is fast, flexible and allows remote quality checks of processed imaging data, facilitating data sharing and collaboration across multiple locations. With the growing trend of open data and open science, such a tool will become increasingly important to share and publish the results of imaging analysis.

The source code for MilxXplore is available at: http://milxview.csiro.au/MilxXplore/?q=content/download.

Acknowledgments

AIBL is a large collaborative study and a complete list of contributors can be found at the website http://www.aibl.csiro.au. The authors would like to thank all who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: PB, JF and VD contributed to the conception and design of the study/software and drafting the article. OS, CCR and VLV contributed to critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: This research is supported by the Science and Industry Endowment Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study received ethics approval from St Vincent's Hospital, Melbourne, Austin Health, Edith Cowan University and Hollywood Private Hospital Human Research Ethics Committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Thal LJ, et al. Ways towards an early diagnosis in Alzheimer's disease: the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Alzheimers Dement 2005;1:55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis KA, Bush AI, Darby D, et al. the AIBL Research Group The Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging: methodology and baseline characteristics of 1112 individuals recruited for a longitudinal study of Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:672–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marek K, Jennings D, Lasch S, et al. The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol 2011;95:629–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Martino A, Castellanos X, Anderson J, et al. The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) consortium: open sharing of autism resting state fMRI [abstract]. OHBM, 2012

- 5.Frontotemporal-lobar-degeneration-neuroimaging-initiative: http://www.radiology.ucsf.edu/cind/research/grants/frontotemporal-lobar-degeneration-neuroimaging-initiative

- 6.Marcus DS, Wang TH, Parker J, et al. Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS): cross-sectional MRI data in young, middle aged, nondemented, and demented older adults. J Cogn Neurosci 2007;19:1498–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus DS, Fotenos AF, Csernansky JG, et al. 2009 Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS): longitudinal MRI data in nondemented and demented older adults. J Cogn Neurosci 2007;22:2677–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toga AW, Clark KA, Kristi A, et al. Mapping the human connectome. Neurosurgery 2012;71:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus DS, Olsen T, Ramaratnam M, et al. The Extensible Neuroimaging Archive Toolkit (XNAT): an informatics platform for managing, exploring, and sharing neuroimaging data. Neuroinformatics 2007;5:11–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burdett N, Fripp J, Bourgeat P, et al. MILXView: a medical imaging, analysis and visualization platform. IFIP Adv Info Commun Technol 2010;335:177–86 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischl B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 2012;62:774–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torri F, Dinov ID, Zamanyan A, et al. Next generation sequence analysis and computational genomics using graphical pipeline workflows. Genes 2012;3:545–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashburner J. SPM: a history. Neuroimage 2012;62:791–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, et al. FSL. NeuroImage 2012;62:782–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neubert A, Fripp J, Engstrom C, et al. Automated detection, 3D segmentation and analysis of high resolution spine MR images using statistical shape models. Phys Med Biol 2012;57:8357–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paproki A, Sirault X, Berry S, et al. A novel mesh processing based technique for 3D plant analysis. BMC Plant Biology 2012;12:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]