Abstract

Background

Revision in failed shoulder arthroplasty often requires removal of the humeral component with a significant risk of fracture and bone loss. Newer modular systems allow conversion from anatomic to reverse shoulder arthroplasty with retention of a well-fixed humeral stem. We report on a prospectively evaluated series of conversions from hemiarthroplasty to reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Methods

In 14 cases of failed hemiarthroplasty due to rotator cuff deficiency and painful pseudoparalysis (in 13 women), revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty was performed between October 2006 and 2010, with retention of the humeral component using modular systems. Mean age at the time of operation was 70 (56–80) years. Pre- and postoperative evaluation followed a standardized protocol including Constant score, range of motion, and radiographic analysis. Mean follow-up time was 2.5 (2–5.5) years.

Results

Mean Constant score improved from 9 (2–16) to 41 (17–74) points. Mean lengthening of the arm was 2.6 (0.9–4.7) cm without any neurological complications. One patient required revision due to infection.

Interpretation

Modular systems allow retainment of a well-fixed humeral stem with good outcome. There is a risk of excessive humeral lengthening.

Revision surgery in failed shoulder arthroplasty remains a technically challenging operation associated with less predictable results and higher complication rates when compared to primary shoulder arthroplasty (Wall et al. 2007, Zumstein et al. 2011). Failure results from a combination of bone and soft tissue deficiency as well as secondary rotator cuff insufficiency, infection, neural injuries, and implant-associated complications. Fracture arthroplasty has a risk of resorption, malunion, and dislocation of the tuberosities (Zyto et al. 1998, Boileau et al. 2002, Hasan et al. 2002). Secondary rotator cuff insufficiency leads to anterosuperior migration of the humeral component and painful pseudoparalysis. In these cases, revision to a reverse shoulder arthroplasty may give better functional results and pain reduction (Levy et al. 2007a, b, Flury et al. 2011).

Primary shoulder arthroplasty is mostly performed with a stemmed implant. Revision of a stemmed prosthesis often requires removal of the cemented or bony ingrown humeral shaft. When there are well-fixed components, the humerus is at risk of intraoperative fracture, longer operating time, and blood loss. Removal of cement and the humeral component may require a humeral cortical window. In some cases, there may not be enough humeral bone stock left for stable reconstruction of the revision stem afterwards (Sperling and Cofield 2005, Gohlke and Rolf 2007, Johnston et al. 2012).

We hypothesized that newer modular systems allow conversion from anatomic to reverse shoulder arthroplasty with retention of a well-fixed humeral stem. At present, there is limited information regarding this technique and its possible complications. Here we report our results for conversion from hemiarthroplasty to reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

Patients and methods

From October 2006 through 2010, the senior author (FG) performed 119 revision arthroplasties to a reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Patients met the inclusion criteria for this prospective study if they had a failed modular hemiarthroplasty due to secondary rotator cuff insufficiency and painful pseudoparalysis, and if modular adapter components for conversion were available. In addition, a negative preoperative history of infection, absence of local or systemic signs of infection, and inconspicuous markers of inflammation including C-reactive protein and leukocyte count were required. 37 patients fulfilled these criteria. In 13 cases of intraoperatively loose humeral components and excessive soft-tissue contractures despite an appropriate release that did not allow reduction with the original humeral stem in place, and in 10 cases with intraoperative findings suspicious of infection, a 1- or 2-stage revision including removal of the humeral stem was required.

Retention of the humeral shaft could be achieved in the remaining 14 patients (13 women) using implants of 5 different companies (Mathys, Zimmer Medical, Tornier, Lima, and Implantcast). Indications for the index operation included fracture (8 cases), cuff tear arthropathy (5 cases) and tumor (1 case). Mean age at the time of operation was 70 (56–80) years. All patients had a deficiency or atrophy of the anterior deltoid muscle due to previous surgery. Mean operating time was 141 (88–215) min. Mean follow-up time was 2.5 (2–5.5) years.

Clinical and radiographic evaluation

Pre- and postoperative examination included Constant-Murley score. Pain was assessed using VAS. Range of motion was measured for active and passive elevation, abduction, and rotation. Internal rotation was documented to the level of the spinal region reached with the thumb. Integrity of the 3 parts of the deltoid muscle was assessed clinically for muscular contraction and positive lag-sign. Electrodiagnostic studies were used to confirm clinical suspicion of denervation of the deltoid muscle.

Patient satisfaction was rated as “very satisfied”, “satisfied”, “fair”, or “disappointed”. Radiographic examination was performed pre- and postoperatively including true anteroposterior and axillary projections. In addition, we used preoperative CT-scans and ultrasonography to determine the quality of the residual rotator cuff and glenoid bone stock as well as signs of humeral component loosening. Postoperative radiographs were evaluated for evidence of humeral and glenoid component loosening, heterotopic ossification, and inferior glenoid notching.

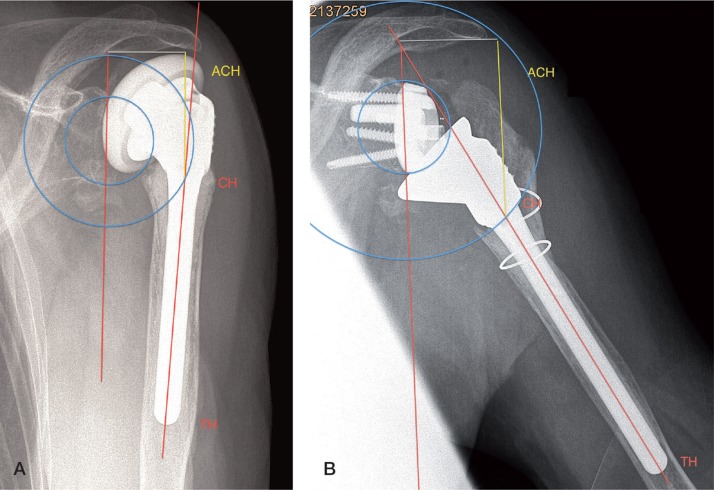

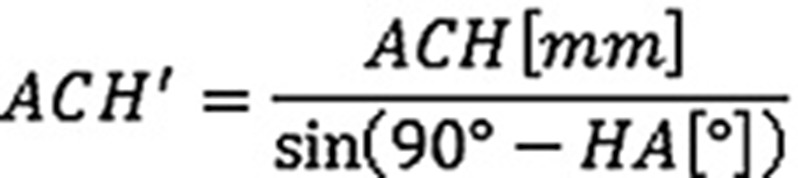

Measurements were made from true anteroposterior radiographs using a digital caliper (Figure) with positioning of the patient’s arm parallel to the cassette in neutral rotation. The diaphyseal axis was drawn as a line passing centrally through the medullary canal. Humeral abduction was calculated as the angle between the glenoid plane and the diaphyseal axis. To correct for magnification, the length of the diaphyseal part of the humeral stem was measured from the distal tip of the humeral component (TH) to the connecting point between the metaphyseal and diaphyseal humeral component crossing the diaphyseal axis (CH). The center of the glenoid baseplate was taken as the center of rotation (COR). A circle was drawn from the center of the glenoid to point CH. Afterwards the distance between the inferolateral tip of the acromion and point CH was measured (ACH). To correct for difference in humeral abduction (HA), we used the following formula:

|

Measurement of lengthening of the arm was performed preoperatively (panel A) and postoperatively (panel B) on true anteroposterior radiographs. Measurement was corrected for humeral abduction and magnification. CH: connecting point between metaphyseal and diaphyseal humeral components; TH: distal tip of the humeral component; ACH: distance between the inferolateral tip of the acromion and point CH.

Postoperative lengthening of the arm was calculated as the difference between pre- and postoperative ACH’. This measurement depends on the glenosphere and polyethylene insert chosen.

Surgical technique

Operation was performed preferably using a deltopectoral approach. If a different approach had been used for the previous surgery, it was also used if it was deemed appropriate for exposure. Scar formations were properly dissected, and a cautious subacromial release and mobilization of the remnants of the rotator cuff were performed. If possible, remnants of the infraspinatus and teres minor tendon were preserved. Joint fluid aspirations and tissue biopsies were taken to search for infection, and antibiotics were given postoperatively. Cultures were kept for 2 weeks to detect slow-growing pathogens such as Propionibacterium species. After dislocation of the prosthesis and removal of the metaphyseal component, the humeral shaft was checked for stable fixation. Afterwards, a subperiostal and periglenoidal release was performed for proper exposure of the glenoid. The glenoid baseplate was placed on the inferior part of the glenoid with a slight inferior tilt (< 10°) to reduce the incidence of postoperative glenoid notching. After fixation of the glenosphere, trial repositioning was performed using an adequate metaphyseal trial component to restore joint stability. As all but 1 type of prosthesis (Lima) did not permit complete removal of the metaphyseal component, the insertion of an additional humeral adapter due to implant design complicated prosthetic reduction. This metaphyseal “onlay” technique resulted in additional lateralization of the humeral component, causing advanced tensioning of the soft-tissues. Following insertion and reduction of the prosthesis, a double-row side-to-side reconstruction of the subscapularis tendon was performed if possible.

Postoperative treatment followed a standardized protocol involving 6 weeks of immobilization in an abduction splint accompanied by passive physiotherapy. Patients underwent postoperative antibiotic treatment consisting of amoxicillin and sulbactam until cultures were found to be negative.

Statistics

Pre- and postoperative data were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank sum test. Correlation between arm lengthening and clinical outcome or prosthetic design was assessed with Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The cutoff for statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. All investigations conformed to ethical principles of research, and we obtained informed consent for participation in the study from all 14 patients.

Results

Constant score improved from 8.9 (2–16) points to 41 (17–74) points postoperatively (p < 0.001). The age- and sex-related Constant score improved from 13% (3–26) to 59% (25–91) (p < 0.001). All subgroups of the score showed a significant increase (Table 1). Mid-elevation increased from 51° to 98° (p < 0.001) and active abduction increased from 38° to 82° (p < 0.001). Mean external rotation postoperatively was 10°. Internal rotation was improved to L3 in 2 patients, whereas all others were able to reach the sacrum.

Table 1.

Clinical outcome of 14 patients following revision of failed hemiarthroplasty to reverse shoulder arthroplasty

| Preoperatively | At last follow-up | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Constant score (range) | |||

| Total | 9 (2–16) | 41 (17–74) | < 0.001 |

| Pain | 1.4 (0–4) | 11 (5–14) | < 0.001 |

| Activity | 2.9 (0–4) | 11 (6–18) | < 0.001 |

| Mobility | 4.6 (0–12) | 16 (6–30) | < 0.001 |

| Strength | 0 | 3.4 (0–15) | 0.008 |

| Mean active range of motion in degrees (range) | |||

| Elevation | 51 (20–100) | 98 (50–150) | 0.003 |

| Abduction | 38 (10–70) | 82 (40–140) | 0.006 |

| External rotation (0°) | 1 (0–5) | 10 (0–30) | 0.008 |

Intraoperative biopsies and joint aspirations were positive in 5 cases; 3 of them had been revised for failed fracture arthroplasty. We detected coagulase-negative Staphylococcus in 4 patients and Propionibacterium acnes in 1 patient. Following performance of a resistogram, antibiotic treatment was adjusted with amoxicillin/sulbactam for 6 weeks.

Radiographic analysis showed arm lengthening of 2.6 (0.9–4.7) cm (Table 2). In all cases, the shortest metaphyseal component, the smallest polyethylene insert, and a 36-mm glenosphere were implanted. Any influence of these parameters on postoperative lengthening could therefore be excluded. We did not find a correlation between arm lengthening and outcome parameters, underlying diagnosis, or type of prosthesis.

Table 2.

Patient data and radiographic findings

| Patient | Sex | Side | Age at surgery | Type of prosthesis | ACH’, postoperatively | mm preoperatively | Arm lengthening, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | L | 77 | Mathys | 53 | 72 | 19 |

| 2 | F | R | 61 | Mathys | 55 | 64 | 9 |

| 3 | F | L | 67 | Lima | 58 | 101 | 44 |

| 4 | F | R | 74 | Tornier | 49 | 67 | 18 |

| 5 | F | L | 79 | Mathys | 43 | 82 | 39 |

| 6 | F | R | 56 | implantcast | 46 | 61 | 15 |

| 7 | M | R | 66 | Zimmer | 49 | 72 | 23 |

| 8 | F | R | 70 | Zimmer | 44 | 58 | 13 |

| 9 | F | R | 79 | Tornier | 33 | 80 | 48 |

| 10 | F | R | 63 | Zimmer | 42 | 53 | 11 |

| 11 | F | R | 72 | Mathys | 33 | 73 | 40 |

| 12 | F | R | 60 | Mathys | 45 | 74 | 29 |

| 13 | F | R | 72 | Mathys | 47 | 75 | 28 |

| 14 | F | R | 70 | Zimmer | 28 | 59 | 31 |

There were no radiographic signs of component loosening or glenoid notching at the latest follow-up. There was no dislocation or fatigue fracture of the acromion or scapular spine. Despite a mean arm lengthening of 2.6 cm, we could not find any evidence of neural injuries or chronic regional pain syndrome at the postoperative follow-up.

We observed 2 postoperative complications. 1 patient developed a deep infection with Staphylococcus epidermidis 10 months postoperatively after incision of a sudoriferous abscess. The infection was treated successfully with open lavage and exchange of the polyethylene insert. Intraoperative screening at the initial revision surgery had been negative. The other patient complained of persistent pain after surgery. We thought that this was due to baseplate loosening even though we did not find any radiographic evidence. Intraoperatively, glenoid bone stock was assessed critical to stable initial fixation of the glenoid baseplate. Regarding the subjective postoperative outcome, 5 patients were very satisfied and 5 were satisfied. 2 patients rated the outcome as fair and 2 were disappointed, both of whom had had postoperative complications.

Discussion

Revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty is an option in the treatment of failed anatomic prostheses. The reverse prosthesis is designed to compensate for an insufficient rotator cuff by recruiting anterior and posterior fibers of the deltoid muscle. Restoration of deltoid tension results in lengthening of the arm. There is currently no guideline for correct soft-tissue balancing. Intraoperative assessment of stability is usually based on the surgeon’s experience and is therefore somewhat subjective. Boileau et al. (2005) postulated that a lengthening of 15 mm would be sufficient for stability. Improper retensioning of the deltoid may lead to shortening of the arm, causing a high risk of prosthetic dislocation. In contrast, excessive lengthening may result in abduction contractures and early baseplate loosening from the forces pulling upward on the humeral side. Elderly patients with osteoporotic bone are especially at risk of acromial or scapular spine fatigue fractures. Neurological complications appear to correlate with arm lengthening (Lädermann et al. 2011). However, extended preparation of soft-tissues, intraoperative vascular and neural injuries, and the interscalene block also appear to play a role—as some patients with substantial arm lengthening do not show any neurological complications (Lädermann et al. 2009).

In a recently published study, Lädermann et al. (2012) followed 183 patients who had received a reverse shoulder arthroplasty for at least 20 months. In comparison to the healthy contralateral side, a mean lengthening of the arm of 1.6 cm was detected. Patients with postoperative shortening of the arm and reduced deltoid tensioning showed poorer functional outcome. In contrast to their findings in a previous study, the authors did not find a correlation between humeral lengthening and outcome (Lädermann et al. 2009). Our patients developed an arm lengthening of approximately 2.6 cm. We found no mechanical or neurological complications. This may be due to a less aggressive postoperative treatment involving 6 weeks of immobilization in an abduction splint and passive rehabilitation. In addition, clinically all the patients had a deficiency or atrophy of the anterior deltoid muscle due to the previously performed surgery. The resulting reduced tensioning of the deltoid muscle may explain reduced mechanical stress on the acromion and scapular spine. Excessive arm lengthening following insertion of a humeral adapter may nevertheless result in neurological complications as well as fatigue fractures and glenoid baseplate loosening, even though it did not occur in our patients.

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in posttraumatic arthritis and revision surgery are still associated with less predictable results and higher complication rates than with cuff tear arthropathy (Boileau et al. 2005, Guery et al. 2006, Jouve et al. 2006, Wall et al. 2007). In a recently published survey, Austin et al. (2011) compared 28 reverse prostheses implanted for primary or revision surgery. In the revision group, they found poorer functional results and a higher complication rate than in the primary reverse arthroplasties (one-third as compared to one-fifth).

Failure of an anatomic prosthesis is multifactorial but is more often related to complications associated with the glenoid side than to humeral complications. Cil et al. (2009) presented a study on 125 revision arthroplasties with a 20-year survival rate of 83%. More than half of their re-revisions had to be performed due to glenoid pathologies. Levy et al. (2007b) reported on 19 revision operations with the reverse prosthesis for failed hemiarthroplasty. In all cases, the previously used prosthesis was completely removed. Substantial pain reduction, gain in mobility, and an increase in ASES score of up to 61 points were found at a mean of 4 years postoperatively. 17 patients were satisfied with the outcome and 6 required reoperation. More implant-related complications occurred in cases with severe bone defects. Melis et al. (2010) presented a multicenter study on 37 patients who had revision of a total shoulder arthroplasty to a reverse arthroplasty due to glenoid pathologies. There were complications in 11 patients, with reoperations in 8 patients because of persistent glenoid loosening. Increased Constant score, pain relief, and gain in forward elevation was noted.

If one assumes that the humeral side is less often the cause of failure, one could question the necessity of extracting the humeral shaft in these cases. Modular systems may help to minimize extraction-related complications, especially with a well-fixed humeral stem.

In order to avoid intraoperative fracture of the bone, a humeral osteotomy may be necessary to facilitate humeral stem extraction. Different techniques have been described in the literature. Even so, there are also technique-related complications such as non-union of the cortical window, dislocation, and fracture (Johnston et al. 2012, Gohlke and Rolf 2007, Sperling and Cofield 2005). Walker et al. (2012) studied 22 patients following revision of failed total shoulder arthroplasty with a reverse implant, with extraction of the humeral shaft. The patients showed improvement in ASES score, pain, function, and range of motion. There were complications in 5 patients. Kelly et al. (2012) reported on 28 patients with a minimum follow-up of 2 years after revision to a reverse shoulder arthroplasty with extraction of the humeral shaft. The age- and sex-related Constant score increased from 24% to 65% and mean forward elevation was 108° at the latest follow-up. Despite a high level of satisfaction in 24 patients, there were complications in 14 patients with reoperations in 7.

There have been few reports on revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty without stem removal. Verborgt et al. (personal communication) reported on 15 patients with an improvement in Constant score from 25 to 46 points at 1 year postoperatively. In 1 patient, they noted glenoid baseplate loosening. Patel et al. (2012) followed 28 patients for an average of 3 years. Retention of the humeral stem could be achieved in 6 cases. The patients improved in ASES and VAS score and forward elevation increased. There were complications in 3 patients. We noted similar outcomes in patient satisfaction and functional improvement. We had a relatively low complication rate (2/14) compared to the above-mentioned studies. This may have been due to the surgical technique and restrictive postoperative rehabilitation.

However, findings suggestive of infection require extraction of the humeral shaft and a 2-stage revision (Gohlke and Rolf 2007, Walker et al. 2012). Patients claiming pain and stiffness after shoulder arthroplasty without any clinical or laboratory hint of infection are especially likely to carry low-virulence organisms (Levy et al. 2012). The literature indicates higher infection rates in revision surgery and in patients with a history of trauma (Zumstein et al. 2011, Singh et al. 2012). Topolski et al. (2006) reported 17% positive cultures in a series of 439 patients undergoing revision shoulder arthroplasty, with isolation of Propionibacterium acnes in 60% of the positives. Kelly and Hobgood (2009) noted positive intraoperative cultures in one-third of presumed aseptic revision shoulder arthroplasty. Rates of subsequent infections ranged from 13% to 25%, with a high incidence of low-virulence bacteria (Topolski et al. 2006, Kelly and Hobgood 2009, Foruria et al. 2012). The clinical relevance of unexpected positive cultures is controversial. Our protocol included intraoperative cultures and postoperative antibiotic therapy until anaerobic cultures were found to be negative. In our series, we had positive cultures in 5 of 14 cases without any correlation with the underlying diagnosis. We did not observe any subsequent infections, probably due to postoperative antibiotic treatment.

In summary, we found revision of failed shoulder arthroplasty to be a technically demanding procedure with improved but still limited functional results. Modular design of shoulder arthroplasty allowed conversion from anatomic to reverse shoulder arthroplasty without removal of a well-fixed humeral component, which reduced the risk of humeral shaft fracture. However, outcome analysis of our study was limited by the relatively short follow-up and the limited number of cases, and also by the use of several implants and the different underlying pathologies.

Acknowledgments

BSW designed the study, gathered and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. DB also gathered and analyzed the data. FG designed the study and proofread the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Austin L, Zmistowski B, Chang ES, Williams G R., Jr Is reverse shoulder arthroplasty a reasonable alternative for revision arthroplasty? . Clin Orthop. 2011;469:2531–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1685-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Tinsi L, Walch G, Coste JS, Mole D. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:401–12. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: Design, rationale and biomechanics . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:147S–161S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cil A, Veillette CJ, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW, Schleck C, Cofield RH. Revision of the humeral component for aseptic loosening in arthroplasty of the shoulder . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91:75–81. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flury MP, Frey P, Goldhahn J, Schwyzer HK, Simmen BR. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty as a salvage procedure for failed conventional shoulder replacement due to cuff failure – midterm results . Int Orthop. 2011;35:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-0990-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foruria AM, Fox TJ, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Clinical meaning of unexpected positive cultures (UPC) in revision shoulder arthroplasty . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):620–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke F, Rolf O. Revision of failed fracture hemiarthroplasties to reverse total shoulder prosthesis through the transhumeral approach: method incorporating a pectoralis-major-pedicled bone window . Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19:185–208. doi: 10.1007/s00064-007-1202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88:1742–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan SS, Leith JM, Campbell B, Kapil R, Smith KL, Matsen FA. Characteristics of unsatisfactory shoulder arthroplasties . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:431–41. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.125806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston PS, Creighton RA, Romeo AA. Humeral component revision arthroplasty: outcomes of a split osteotomy technique . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:502–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouve F, Wall B, Walch G. Sauramps Medical. Montpellier: 2006. Revision of shoulder hemiarthroplasty with reverse prosthesis. In: Reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clinical results – complications – revisions (eds. Walch et al) ; pp. 217–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J D. 2nd, Hobgood ER. Positive culture rate in revision shoulder arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2009;(467):2343–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0875-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J D. 2nd, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1516–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lädermann A, Williams MD, Melis B, Hoffmeyer P, Walch G. Objective evaluation of lengthening in reverse shoulder arthroplasty J Shoulder Elbow Surg . 2009;18:588–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lädermann A, Lübbeke A, Melis B, Stern R, Christofilopoulos P, Bacle G, Walch G. Prevalence of neurologic lesions after total shoulder arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93:1288–93. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lädermann A, Walch G, Lubbeke A, Drake GN, Melis B, Bacle G, Collin P, Edwards TB, Sirveaux F. Influence of arm lengthening in reverse shoulder arthroplasty . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J, Frankle M, Mighell M, Pupello D. The use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007a;89:292–300. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JC, Virani N, Pupello D, Frankle M. Use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral arthritis and rotator cuff deficiency . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007b;89:189–95. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.18161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy O, Iyer S, Atoun E, Peter N, Hous N, Cash D, Musa F, Narvani A. Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated aetiology in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis? . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):505–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis B, Bonnevialle N, Neyton N, Walch G, Boileau P. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2010. Aseptic glenoid loosening or failure in total shoulder arthroplasty: Results of revision with reverse shoulder arthroplasty. In: Shoulder concepts 2010: The glenoid (eds. Walch G, Boileau P, Mole D, Favard L, Levigne C, Sirveaux F) ; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Patel DN, Young B, Onyekwelu I, Zuckerman JD, Kwon YW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for failed shoulder arthroplasty . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1478–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Sperling JW, Schleck C, Harmsen W, Cofield RH. Periprosthetic infections after shoulder hemiarthroplasty . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1304–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Humeral windows in revision shoulder arthroplasty . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:258–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topolski MS, Chin PY, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision shoulder arthroplasty with positive intraoperative cultures: the value of preoperative studies and intraoperative histology . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89:1476–85. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumstein MA, Pinedo M, Old J, Boileau P. Problems, complications, reoperations and revisions in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyto K, Wallace A, Frostick SP, Preston BJ. Outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:85–9. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]