Abstract

Background and purpose

As much as one-third of all total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 60 years may be a consequence of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). Screening and early treatment of neonatal instability of the hip (NIH) reduces the incidence of DDH. We examined the radiographic outcome at 1 year in children undergoing early treatment for NIH.

Subjects and methods

All children born in Malmö undergo neonatal screening for NIH, and any child with suspicion of instability is referred to our clinic. We reviewed the 1-year radiographs for infants who were referred from April 2002 through December 2007. Measurements of the acetabular index at 1 year were compared between neonatally dislocated, unstable, and stable hips.

Results

The incidence of NIH was 7 per 1,000 live births. The referral rate was 15 per 1,000. 82% of those treated were girls. The mean acetabular index was higher in dislocated hips (25.3, 95% CI: 24.6–26.0) than in neonatally stable hips (22.7, 95% CI: 22.3–23.2). Girls had a higher mean acetabular index than boys and left hips had a higher mean acetabular index than right hips, which is in accordance with previous findings.

Interpretation

Even in children who are diagnosed and treated perinatally, radiographic differences in acetabular shape remain at 1 year. To determine whether this is of clinical importance, longer follow-up will be required.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a continuum of hip joint disease from childhood to adult life, including morphological changes of the joint, instability, and dislocation. Instability and dislocation can often be detected in the neonatal period, when the term neonatal instability of the hip (NIH) is used. NIH can normalize spontaneously (Gardiner and Dunn 1990, Rosendahl et al. 1994, Bialik et al. 1999). Also, cases of late-presenting DDH can be clinically and morphologically normal at birth (Lennox et al. 1993, Raimann et al. 2007) and even up to early school age (Modaressi et al. 2011). Despite such possible crossover, early diagnosis and treatment of NIH clearly reduces the incidence of late DDH (Fredensborg 1976, Hansson et al. 1983, Dunn et al. 1985, Myers et al. 2009).

DDH is a risk factor for osteoarthritis. In the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, in 1987–99 it accounted for 9% of all primary total hip replacements (THRs) and 29% of THRs in patients less than 60 years of age (Furnes et al. 2001). In 1987–2004, 21% of Norwegian THR patients younger than 38 years had DDH (Engesaeter et al. 2008). NIH leads to an increased risk of THR in early adulthood (Engesaeter et al. 2008).

Screening for NIH was initiated in Malmö in 1952, and the treatment program was instituted in 1956. The screening program has already been described in detail (Danielsson 2000, Duppe and Danielsson 2002). It is based on collaboration between pediatricians, radiologists, and orthopedic surgeons. NIH is treated with the von Rosen splint, which was developed at our clinic in the 1950s (Von Rosen 1956). Dislocated hips, i.e. Barlow- or Ortolani-positive (Barlow 1962, Ortolani 1976), and unstable hips (see Patients and Methods for definition) are treated for 12 weeks and 6 weeks respectively. The aim of the treatment is to prevent later hip dysplasia and dislocation. The incidence of late-diagnosed DDH in Malmö was 0.07/1,000 live births between 1990 and 1999 (Duppe and Danielsson 2002), which to our knowledge is the lowest incidence reported in the literature. This figure should be compared to an expected incidence of about 0.9–1.8/1,000 without screening (MacKenzie and Wilson 1981, Hansson et al. 1983).

We compared the radiographic outcome at 1 year of age in children with different levels of hip instability as newborns. This has not been studied previously, either for the von Rosen splint or for the commonly used Pavlik harness, although there have been publications including children treated from 4 months or younger (Elbourne et al. 2002, Wilkinson et al. 2002) and the 1-year radiographic outcome after early treatment with the von Rosen splint has been presented by Hinderaker et al. (1992).

Subjects and methods

All children born at our hospital are examined clinically by a pediatrician within 2–3 days from birth. Those with suspected hip instability or dislocation are referred to the pediatric orthopedic department. In cases where the pediatrician suspects an unstable hip but the Ortolani (1976) or Barlow (1962) signs are not clearly positive, the infant is referred to a dynamic ultrasound examination, as described by Dahlström et al. (1986). The orthopedic surgeon provokes the hip using the Barlow test while the radiologist determines how great a proportion of the femoral head is subluxated from the acetabulum. In this study, all patients referred from April 2002 through December 2007 were eligible for inclusion.

Children with a dislocated hip (we included dislocatable, i.e. Barlow-positive, hips in this category) were treated with the von Rosen splint for 12 weeks. 28% of patients in this group were treated after sonographic diagnosis, and the rest were clearly positive on clinical examination alone. Children whose femoral heads could be subluxated by 25% or more of the diameter according to the dynamic ultrasound were treated with the splint for 6 weeks. The cutoff at 25% was chosen arbitrarily. Children with stable hips did not receive any treatment but underwent identical radiographic follow-up (see below). The hips were divided into 3 groups according to the above criteria: “dislocated” (Barlow- or Ortolani-positive), “unstable” (≥ 25% subluxation), or “stable” (< 25% subluxation). All included children with unstable and stable hips had undergone sonography. Mean age at sonography was 2.8 (1–7) days.

The splint was worn day and night, and parents were discouraged from adjusting or removing it at all. Every week, the patients came to the outpatient clinic to have a bath and check the splint. The follow-up was the same for all referred children and included standard AP radiographs of the pelvis at 3 and 12 months.

Our primary outcome measure was the acetabular index (AI), as described by Hilgenreiner (1986), at the 1-year follow-up (Figure 1). We also looked for signs of avascular necrosis (Kalamchi and MacEwen 1980).

Figure 1.

Example of an AI measurement at 1 year on the left side of a girl treated for bilateral neonatal dislocation (Barlow-positive).

Only cases with a Tönnis index of between 0.56 and 1.8 were included for radiographic analysis. Adherence to this recommendation reduces measurement errors due to rotation in the axial plane (Tonnis 1976). Radiographs where rotation in the sagittal plane made measurements difficult were excluded. Only children with a radiograph within 1 month from their first birthday were included. 3 children were judged by a senior orthopedic surgeon to be unstable without sonography and were therefore excluded. 1 child had been treated for only 1 week due to abduction impairment and was excluded (Figure 2). All radiographs were reviewed by the same author (DW).

Figure 2.

Exclusion analysis.

Inter- and intra-observer variability of measurements

We analyzed the variability of measurements of the AI in 22 randomly chosen patients (44 hips). The measurements were performed independently by 3 investigators (DW, CJT, and HD). Each investigator measured the same hips twice at an interval of at least 3 months. The systematic error was used to exclude a systematic difference between the first and second measurement for each investigator. It was calculated according to Formula 1.

Formula 1: Systematic error = (mean of measurement 1 – mean of measurement 2) / 2

The coefficient of variation in percent (CV%) was used to describe the intra-observer variability. CV% shows the random error relative to the parameter analyzed. CV% is calculated according to Formulae 2a and 2b.

Formula 2a: Random error = SD of ((measurement 1 – measurement 2) / √2 )

Formula 2b: CV% = (random error / overall mean ) × 100

The inter-observer variability was calculated as the difference between the mean of the 2 measurements performed for each hip by one investigator and the mean of all 6 measurements for that hip, expressed as a percentage of the overall mean.

The systematic error in measurements of AI was 0.05 (0.2%), –0.13 (0.5%), and 0.26 (1.1%) for the 3 investigators. The CV% for each investigator was 3.3% (95% CI: 3.1–3.5), 5.1% (4.8–5.5), and 5.7% (5.4–6.1), respectively. 85% of all values measured were within 5% of the mean AI for that hip, as measured by all 3 investigators on 2 occasions. The average deviations from the mean were 2.9%, 2.8%, and 2.6%, respectively, for the 3 investigators. (For a hip with an AI of 22, a 2.9% deviation equals 0.6).

Software and statistics

Radiographs were stored and viewed using Impax CS5000 (Agfa). For comparison of baseline statistics between groups, the chi-square test was used. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of acetabular indices between groups of patients. The Shapiro-Wilk statistic was 0.99 for AI measurements of stable, unstable, and dislocated hips and ranged from 0.96 to 1.00 for all subgroups analyzed.

Results

Epidemiology

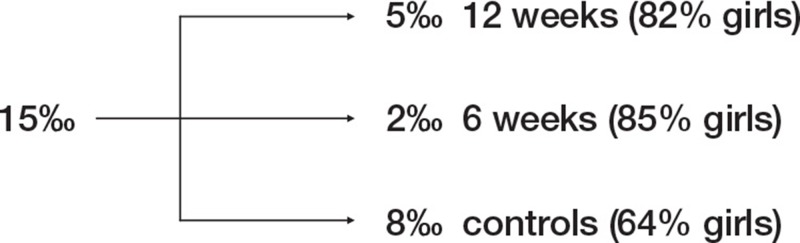

From April 2002 through December 2007, there were 22,517 live births at our hospital and 332 children were referred for examination at our clinic. The incidence of referral was 15/1,000 live births (Figure 3). Of all the children referred, 241 (73%) were girls. 111 children (91 of whom were girls) were treated with the von Rosen splint for 12 weeks. 47 children (40 girls) were treated for 6 weeks. 173 of those referred (110 girls) had bilaterally stable hips. Of the 111 cases with dislocation, 38 (34%) were bilateral, 16 (14%) had an unstable contralateral hip, and 57 (51%) had a stable contralateral hip.

Figure 3.

The incidence of NIH in Malmö during the study period. 15‰ of all children born in Malmö were referred because of suspected NIH. 5‰ had a dislocated hip. 2‰ had an unstable hip. 8‰ had bilaterally stable hips. This is comparable to previously published data from 1990–97 (Danielsson 2000). Numbers in parentheses denote the percentage of girls in each group.

Radiography

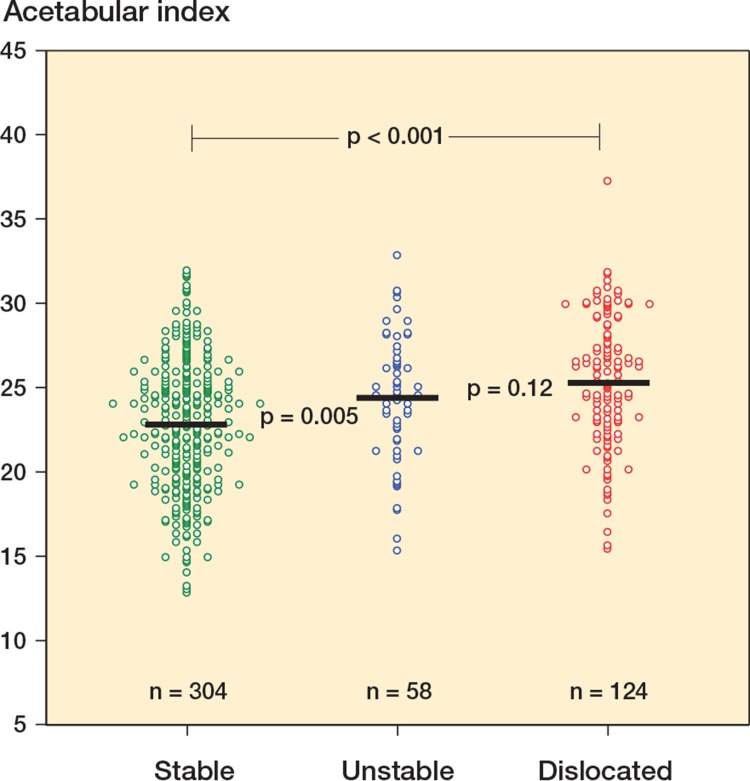

243 children (73% of all referred) met the inclusion criteria for the radiographic study. Dislocated and unstable hips had a higher mean AI than stable hips at 1 year of age (Figure 4). We found no difference between Barlow-positive and Ortolani-positive hips (mean AI = 25.2, CI: 24.4–26.0 vs. 25.4, CI: 24.0–26.9, respectively; p = 0.9). There was no difference in this respect between dislocated and unstable hips (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The mean AI at 1 year was higher for dislocated hips (25.3, 95% CI: 24.6–26.0) and unstable hips (24.3, CI: 23.3–25.3) than for stable hips (22.7, CI: 22.3–23.2). Each circle represents an individual hip. p-values for the comparisons are given.

Of the 55 children with unilateral dislocation and a stable contralateral hip, 52 were eligible for radiographic analysis. These clinically stable hips had a higher mean AI at 1 year than hips of children with bilaterally stable hips (24.5, CI: 23.4–25.6 vs. 22.3, CI: 21.8–22.8; p < 0.001).

Mean AI was 0.6 (CI: 0.2–0.9) higher in left hips than in right hips (p = 0.002, paired analysis). The difference was statistically significant when we only analyzed cases treated for 12 weeks (p = 0.001). However, the mean AI was similar in right and left hips in children who were treated for 6 weeks: 23.3 (CI: 22.1–24.4) vs. 24.1 (CI: 22.8–25.3) and in those with bilaterally stable hips 22.2 (CI: 21.5–23.0) vs. 22.4 (CI: 21.6–23.1).

Girls had a higher mean AI than boys (p = 0.002): 23.9 (CI: 23.5–24.3) vs. 22.6 (CI: 21.9–23.3). The difference remained when we analyzed right and left hips separately (p = 0.02 right, p = 0.04 left).

There were no cases of avascular necrosis (Kalamchi grade 2 or higher). 2 controls and 5 treated children had asymmetrical ossification of the femoral head nuclei. 2 of the children with asymmetrical ossification (both treated) had radiographs taken at 4 or 3.5 years for other reasons, which were normal and symmetrical. None of these 7 children had a later-detected avascular necrosis; they are now 5–10 years old.

Discussion

Our main finding is that NIH leads to a higher acetabular index compared to neonatally stable hips at 1 year of age despite early treatment with abduction splinting. The highest values measured in each group were similar, being between 31 and 32 (except for 2 outliers among the dislocated and unstable hips). However, the proportion of high values, corresponding to dysplasia, increased on moving from stable hips to dislocated hips (Figure 4). Hips with AI of > 29 constitute 4% of stable hips, 9% of unstable hips, and 23% of dislocated hips.

It has previously been stated that treatment with abduction splinting leads to normalization of the hip in most cases (at 5-year follow-up of children born 1970–1979) (Dunn et al. 1985). We are not aware of any long-term follow-up studies on the natural history of NIH; nor has there been any randomized controlled trial comparing early abduction splinting with no treatment. However, there have been studies demonstrating that early diagnosis and treatment of NIH lowers the incidence of late DDH (Fredensborg 1976, Hansson et al. 1983, Dunn et al. 1985, Myers et al. 2009).

In cases with unilateral dislocation, the AI at 1 year was also higher in the clinically stable contralateral hip, despite the fact that these hips had also been splinted. This finding supports the idea that DDH is a general disease and not only based on biomechanical factors.

The female-to-male ratio for dislocated hips was 4:1, which is similar to results from previous investigations (Chan et al. 1997, Elbourne et al. 2002). Girls have a higher AI than boys on average (Tonnis 1976), and women have a higher risk of receiving a THR due to hip dysplasia (3:1) and late-diagnosed dislocation (6:1) (Furnes et al. 2001). DDH is regarded as a disease continuum ranging from neonatal instability to end-stage early osteoarthritis of the hip, and affected by a combination of genetic, hormonal, and mechanical factors.

Although not the main objective of this study, our results demonstrate that the von Rosen splint is safe with regard to avascular necrosis.

There are some difficulties that should be considered when studying NIH and DDH: (1) the definition of NIH and DDH and outcome measures need to be clearly described; (2) the term NIH refers to instability, which is a somewhat subjective phenomenon. Sonography aids in measuring and quantifying instability with higher precision, but even so it is dependent on the skills of both the physician performing the sonography and the one manipulating the hip (Dunn et al. 1985, Macnicol 1990, Krikler and Dwyer 1992, Fiddian and Gardiner 1994, Wood et al. 2000, Lee et al. 2001); (3) the evaluation of DDH is largely based on radiography, which is imprecise if not taken in a standardized manner regarding rotation of the pelvis (Tonnis 1976). Also, there is known to be inter- and intra-observer variability when examining radiographs (Broughton et al. 1989, Boniforti et al. 1997, Clohisy et al. 2009). Our measurements varied only slightly. One explanation may be that they were made on digital radiographs.

A fundamental issue that applies to both DDH and NIH is where to draw the line between a healthy hip and an ill hip. If one defines disease (DDH) simply by using +2 SD from the average as a cutoff, the incidence will be 2.5% regardless of the values measured or of the prevalence of hip symptoms in that population. If using the normal values described by Tönnis (1976) to define disease, a hip with an AI of 27 will be labeled severely dysplastic if situated on the right side of a male pelvis but will not even be considered slightly dysplastic if situated on the left side in a girl (normal values at 10–12 months of age). This way of defining disease does not seem reasonable. Note that we found no difference in AI between right and left hips in the control group, which there is in a general population of 1-year-olds (Tonnis 1976). On the other hand, if we do not use normal values at all, the cutoff between well and ill will be completely arbitrary. There are very few data linking early morphologic changes to long-term clinical outcome.

The clinical examination is dependent on the skill of the examiner (Dunn et al. 1985, Macnicol 1990, Krikler and Dwyer 1992, Fiddian and Gardiner 1994, Lee et al. 2001). In our series, all cases referred had been examined by 1 of 46 pediatricians. All the children except 10 were re-examined by 1 of 3 senior pediatric orthopedic surgeons. We agree with Macnicol (1990) that the primary examination may be the most important one. The low incidence of late-presenting DDH (0.07 in 1,000 live births) (Duppe and Danielsson 2002)) in our program, and the high rate of treatment of referred cases (48% in this series) is mainly thanks to our colleagues at the pediatric clinic, who perform the actual screening.

The role of sonography in screening for NIH is controversial. Assessment of hip morphology sonographically has been shown to be both more sensitive (Severin 1956) and more specific (Dogruel et al. 2008) than clinical examination. However, a randomized controlled trial failed to show any effect of sonographic screening on the incidence of late-diagnosed dislocations (Rosendahl et al. 1994). We use sonography as a means of reducing the rate of over-treatment in NIH. The purpose of the present study was only to present the radiographic outcome using our clinical protocol. We did not aim to make recommendations about screening protocols, including the use of sonography.

Limitations of the study

Our control group consisted of children who had been referred on suspicion of hip abnormality but who were found to be stable by dynamic ultrasound. Thus, they are not truly representative of the average infant, which is obvious since two-thirds of the controls were girls. It is possible both that the control children had less stable hips than the average child, since suspicion arose, or better stability than average, as they were all cleared by dynamic sonography. However, it would be ethically questionable to perform random radiography on 1-year-olds today.

All radiographic measurements were performed by the same investigator (DW), thus eliminating inter-observer variability but not intra-observer variability. The intra-observer variability was low. However, both radiographic analysis and sonography are techniques with inherent imprecision.

There was a higher rate of follow-up in children who had been treated in the splint (87 vs. 69%, p < 0.001). We do not believe that this affected the results, although there was a potential selection bias.

Summary

We found radiographic differences between neonatally dislocated or unstable hips and stable hips at 1-year follow-up, despite early diagnosis and treatment. Future studies will establish whether a high acetabular index at the age of 1 year is related to hip dysplasia and impaired hip function in adulthood.

Acknowledgments

DW: study design, radiographic measurements, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of manuscript. HD and CJT: study design, acquisition of data, and critical revision of the manuscript.

We thank Lars Gösta Danielsson, who initiated the registration of all referrals for NIH in 1987, and Jan-Åke Nilsson of Lund University, for help with the statistical analyses. The study was funded by a grant from the Herman Järnhardt Foundation.

No competing interests declared.

References

- 1.Barlow TG. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1962;44(2):292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, Sujov P, Wiener F, Berant M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence . Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):93–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boniforti FG, Fujii G, Angliss RD, Benson MK. The reliability of measurements of pelvic radiographs in infants . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1997;79(4):570–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b4.7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broughton NS, Brougham DI, Cole WG, Menelaus MB. Reliability of radiological measurements in the assessment of the child’s hip . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1989;71(1):6–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2915007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, Haan EA, Byron-Scott R. Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip . Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997;76(2):F94–100. doi: 10.1136/fn.76.2.f94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilgenreiner WH. Classic (1925). Translation: Hilgenreiner on congenital hip dislocation . J Pediatr Orthop. 1986;6(2):202–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clohisy JC, Carlisle JC, Trousdale R, Kim YJ, Beaule PE, Morgan P, Steger-May K, Schoenecker PL, Millis M. Radiographic evaluation of the hip has limited reliability . Clin Orthop. 2009;467(3):666–75. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlstrom H, Oberg L, Friberg S. Sonography in congenital dislocation of the hip . Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57(5):402–6. doi: 10.3109/17453678609014757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danielsson LG. Instability of the hip in neonates. An ethnic and geographical study in 24,101 newborn infants in Malmo . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2000;82(4):545–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b4.10331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dogruel H, Atalar H, Yavuz OY, Sayli U. Clinical examination versus ultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip . Int Orthop. 2008;32(3):415–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0333-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn PM, Evans RE, Thearle MJ, Griffiths HE, Witherow PJ. Congenital dislocation of the hip: early and late diagnosis and management compared . Arch Dis Child. 1985;60(5):407–14. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.5.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duppe H, Danielsson LG. Screening of neonatal instability of developmental dislocation of the hip . A survey of 132,601 living newborn infants between 1956 and. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002;84(6):878–85. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b6.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elbourne D, Dezateux C, Arthur R, Clarke NM, Gray A, King A, Quinn A, Gardner F, Russell G. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of developmental hip dysplasia (UK Hip Trial): clinical and economic results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial . Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2009–17. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)12024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engesaeter IO, Lie SA, Lehmann TG, Furnes O, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB. Neonatal hip instability and risk of total hip replacement in young adulthood: follow-up of 2,218,596 newborns from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(3):321–6. doi: 10.1080/17453670710015201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiddian NJ, Gardiner JC. Screening for congenital dislocation of the hip by physiotherapists. Results of a ten-year study . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994;76(3):458–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fredensborg N. The results of early treatment of typical congenital dislocation of the hip in Malmo . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1976;58(3):272–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B3.956242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements . A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001;83(4):579–86. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardiner HM, Dunn PM. Controlled trial of immediate splinting versus ultrasonographic surveillance in congenitally dislocatable hips . Lancet. 1990;336(8730):1553–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93318-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansson G, Nachemson A, Palmen K. Screening of children with congenital dislocation of the hip joint on the maternity wards in Sweden . J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3(3):271–9. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinderaker T, Rygh M, Uden A. The von Rosen splint compared with the Frejka pillow. A study of 408 neonatally unstable hips . Acta Orthop Scand (Case reports comparative study) 1992;63:4, 389–92. doi: 10.3109/17453679209154751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalamchi A, MacEwen GD. Avascular necrosis following treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1980;62(6):876–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krikler SJ, Dwyer NS. Comparison of results of two approaches to hip screening in infants . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992;74(5):701–3. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B5.1527116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee TW, Skelton RE, Skene C. Routine neonatal examination: effectiveness of trainee paediatrician compared with advanced neonatal nurse practitioner . Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;85(2):F100–4. doi: 10.1136/fn.85.2.F100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lennox IA, McLauchlan J, Murali R. Failures of screening and management of congenital dislocation of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1993;75(1):72–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B1.8421040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKenzie IG, Wilson JG. Problems encountered in the early diagnosis and management of congenital dislocation of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1981;63(1):38–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B1.7204472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macnicol MF. Results of a 25-year screening programme for neonatal hip instability . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1990;72(6):1057–60. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modaressi K, Erschbamer M, Exner GU. Dysplasia of the hip in adolescent patients successfully treated for developmental dysplasia of the hip . J Child Orthop. 2011;5(4):261–6. doi: 10.1007/s11832-011-0356-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers J, Hadlow S, Lynskey T. The effectiveness of a programme for neonatal hip screening over a period of 40 years: a follow-up of the New Plymouth experience . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91(2):245–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortolani M. Congenital hip dysplasia in the light of early and very early diagnosis . Clin Orthop. 1976;(119):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raimann A, Baar A, Raimann R, Morcuende JA. Late developmental dislocation of the hip after initial normal evaluation: a report of five cases . J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):32–6. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31802b719b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the neonate: the effect on treatment rate and prevalence of late cases . Pediatrics. 1994;94(1):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Severin E. The frequency of congenital hip dislocation and congenital equinovarus in Sweden . Nord Med. 1956;55(7):221–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tonnis D. Normal values of the hip joint for the evaluation of X-rays in children and adults . Clin Orthop. 1976;(119):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Von Rosen S. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip joint . Acta Orthop Scand. 1956;26(2):136–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson AG, Sherlock DA, Murray GD. The efficacy of the Pavlik harness, the Craig splint and the von Rosen splint in the management of neonatal dysplasia of the hip. A comparative study . J Bone Joint Surg (Br)(Comparative study) 2002;84(5):716–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b5.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood MK, Conboy V, Benson MK. Does early treatment by abduction splintage improve the development of dysplastic but stable neonatal hips? . J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(3):302–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]