Abstract

Background

It is unclear whether it is safe to convert above-elbow cast (AEC) to below-elbow cast (BEC) in a child who has sustained a displaced diaphyseal both-bone forearm fracture that is stable after reduction. In this multicenter study, we wanted to answer the question: does early conversion to BEC cause similar forearm rotation to that after treatment with AEC alone?

Children and methods

Children were randomly allocated to 6 weeks of AEC, or 3 weeks of AEC followed by 3 weeks of BEC. The primary outcome was limitation of pronation/supination after 6 months. The secondary outcomes were re-displacement of the fracture, limitation of flexion/extension of the wrist and elbow, complication rate, cast comfort, complaints in daily life, and cosmetics of the fractured arm.

Results

62 children were treated with 6 weeks of AEC, and 65 children were treated with 3 weeks of AEC plus 3 weeks of BEC. The follow-up rate was 60/62 and 64/65, respectively with a mean time of 6.9 (4.7–13) months. The limitation of pronation/supination was similar in both groups (18 degrees for the AEC group and 11 degrees for the AEC/BEC group). The secondary outcomes were similar in both groups, with the exception of cast comfort, which was in favor of the AEC/BEC group.

Interpretation

Early conversion to BEC cast is safe and results in greater cast comfort.

Most displaced diaphyseal both-bone forearm fractures in children can be treated successfully with closed reduction and above-elbow cast (AEC) for 6–9 weeks, but AEC is often converted to below-elbow cast (BEC) in the last weeks of treatment. Although most of these fractures heal uneventfully, limitation of pronation and supination can give disappointing results. Previous studies have found an average limitation of 20 degrees in about 15% of children. The cause of this limitation is unknown, but malunion and contracture of soft tissues have been suggested in some studies (Hogstrom et al. 1976, Nilsson and Obrant 1977, Kay et al. 1986, Tynan et al. 2000, Bhaskar and Roberts 2001, Weinberg et al. 2001, Dumont et al. 2002, Yasutomi et al. 2002, van Geenen and Besselaar 2007).

Early conversion to BEC in the treatment of these fractures could potentially affect limitation of pronation and supination in 2 opposing ways. On the one hand, early conversion to BEC could result in fracture displacement, leading to malunion and resulting in limitation of pronation and supination. On the other hand, AEC may lead to a limitation of pronation and supination because of contracture of soft tissue by immobilization of the elbow.

We therefore set up a randomized controlled multicenter trial to answer the following question: does early conversion from AEC to BEC cause forearm rotation that is similar to that from AEC alone in reduced stable diaphyseal both-bone forearm fractures in children?

Children and methods

Trial design and participants

We performed a multicenter randomized trial on consecutive children with a displaced diaphyseal both-bone forearm fracture that was stable after reduction, who visited the emergency department of one of 4 participating Dutch hospitals: Erasmus Medical Center (Rotterdam), HAGA Hospital (The Hague), Reinier de Graaf Hospital (Delft), and Sint Franciscus Hospital (Rotterdam). The regional medical ethics committee approved the study and it was registered at Clinical Trials.gov with registry identifier NCT00398242. The trial was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all parents and from all children aged ≥ 12 years.

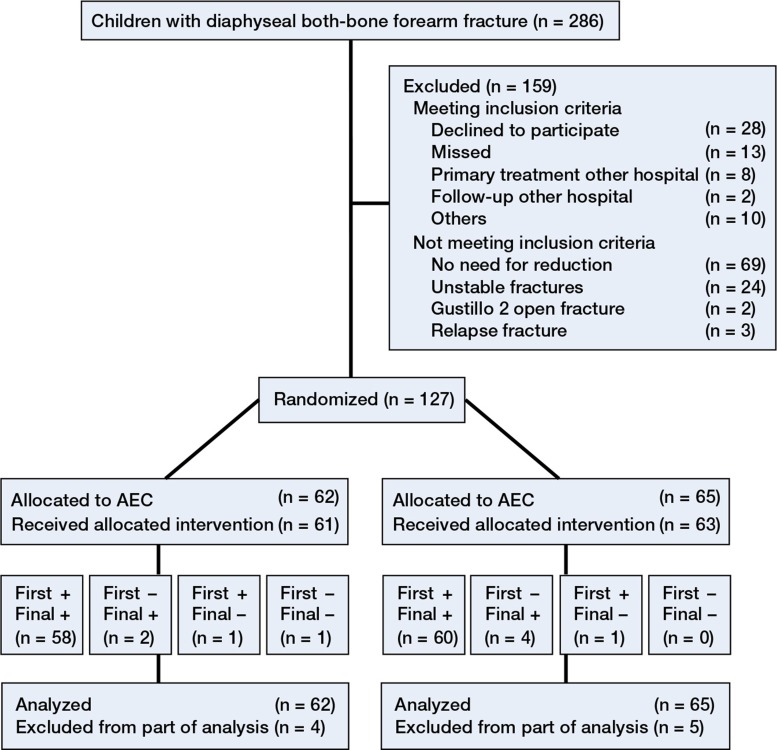

We included all children aged < 16 years who sustained a displaced diaphyseal both-bone forearm fracture that was stable after reduction (Figure 1). A diaphyseal fracture was defined as a fracture in the shaft of the bone between the distal and proximal metaphysis. The criteria for reduction are given in Table 1. Exclusion criteria were unstable fractures, fractures older than 1 week, severe open fractures (Gustilo II and III), and refractures.

Figure 1.

A displaced diaphyseal both-bone fracture.

Table 1.

Criteria for reduction of the fracture of radius and/or ulna based on anteroposterior and/or lateral radiographs

| Type of deformity | Age in years | Deformity |

|---|---|---|

| Angulation | < 10 | > 15 degrees |

| 10–16 | > 10 degrees | |

| Translation | < 16 | > half of bone diameter |

| Rotation | < 16 | > 0 |

Our primary outcome was limitation of pronation and supination 6 months after the initial trauma. The secondary outcomes were re-displacement of the fracture, limitation of flexion and extension of the wrist and elbow, complication rate, cast comfort, complaints in daily life, and cosmetics of the fractured arm.

Procedures

A surgeon reduced the fracture in the operating room under general anesthesia with fluoroscopic guidance. After optimal closed reduction, the fracture was tested for stability. A fracture was defined as unstable if full pronation and supination of the proximal forearm caused re-displacement of the fracture under fluoroscopic vision. This test for stability has been used before in a group of children with forearm fractures (Myers et al. 2004). Unstable fractures (24) were excluded and treated with intramedullary nails. The remaining fractures were defined as stable and were randomized to 6 weeks of AEC or to 3 weeks of AEC followed by 3 weeks of BEC. The surgeon applied an AEC in the operation room. First, a stockinet and layer of wool were applied to protect the skin and bony prominences. Then, a well-fitted plaster slab was applied which covered approximately two-thirds of the circumference of the arm. Finally, a bandage was wrapped around the arm. The elbow was set in 90 degrees of flexion and the forearm in neutral position. All children received a sling for at least 1 week.

The children underwent clinical and radiographic evaluation by a surgeon at 1, 3, and 6 weeks after initial trauma. A cast technician revised this plaster cast to circumferential plaster cast after 1 week and applied a new circumferential synthetic cast after 3 weeks (AEC or BEC). The BEC extended only to the elbow. Fracture displacement, as defined by the loss of reduction according to the primary reduction criteria (Table 1), required new fracture reduction. Finally, the cast was removed 6 weeks after initial treatment.

An orthopedic surgeon (JWC, who was not involved in treatment) examined all children at 2 and 6 months after the initial trauma using a standardized technique to measure flexion and extension of the wrist and elbow, in combination with pronation and supination of both arms (Colaris et al. 2010). The pronation and supination were scaled using a previously employed grading system (Daruwalla 1979) with excellent, good, fair, and poor results for, respectively, 0–10, 11–20, 21–30, and ≥ 31 degrees of limitation. All children with at least 30 degrees of functional impairment at the 2-month examination were referred to a physiotherapist. At the 2-month examination, the parents and children evaluated the comfort of the cast using a visual analog scale (VAS) with highest score for maximal comfort, and a questionnaire to evaluate difficulties in performing 7 daily activities during the period of cast. This questionnaire had previously been used for a similar group of children (Webb et al. 2006).

6 months after the initial trauma, the parents and JWC completed a VAS regarding cosmetics of the fractured arm, with highest score for similar cosmetics in the injured and uninjured arm. In the same consultation, complaints concerning the fractured arm were documented using a modified grading system. This grading system combines limitation of pronation and supination with complaints covering daily life or during strenuous activities. It had been used previously for a similar group of children (Price et al. 1990). Thereafter, the parents filled in an ABILHAND-Kids questionnaire (Arnould et al. 2004), which is a measure of manual ability in children with upper limb impairments.

Radiographs were taken in the emergency room. These were followed by radiographs after reduction and during follow-up at 1, 3, and 6 weeks. The final radiographs were taken 6 months after the initial trauma.

Angulation, translation, rotation, and shortening of fractures were measured on the radiographs to determine primary displacement, displacement during treatment with cast, and final displacement at 6 months. Rotation of the fractured bones was analyzed from differences in the diameter of the diaphysis of the ulna and radius (Naimark et al. 1983). To assess the inter-rater reproducibility, the angulation of the fracture was re-measured in 45 children by a trauma surgeon. The inter-rater reproducibility of the radiological assessment showed an intraclass correlation (ICC) of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.68–0.89) and 0.89 (95% CI: 0.81–0.94) for the radioulnar angulation of the ulna and radius, respectively. The ICC of sagittal angulation was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.85–0.95) for the ulna and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.77–0.92) for the radius.

Randomization and masking

A physician who was not involved in treatment randomized the children using sealed envelopes with varied block sizes. The randomization took place after the fracture was reduced and defined as stable. The study was not blinded regarding the children, parents, and clinicians. JWC collected all the data.

Statistics

This study was an equivalency study in which we wanted to determine whether the index treatment (a combination of AEC and BEC) was no better or worse than the control treatment (AEC alone). The main aim of the study was to address the question: do 6 weeks of AEC, or 3 weeks of AEC and 3 weeks of BEC, cause equal limitation of pronation and supination 6 months after the initial trauma? We assessed the numbers of children required with assumption of similarity of pronation and supination in both groups. Similarity between the 2 groups was defined as a maximum of 15 degrees less pronation or supination in the group treated with AEC and BEC. We chose 15 degrees of limitation to stay within the safe margins of good results as graded previously (Daruwalla 1979). With an a priori calculation, it was determined that with a power of 80%, a significance level of 0.05, and a standard deviation (SD) of 15 degrees, the groups should consist of 30 children each.

First, we assessed whether the variables had a normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Based on these analyses, the results are presented as mean (SD). The primary research question was examined using linear regression analysis. If necessary, adjustments for unbalanced covariates were made. To check for linearity, we plotted the standardized residuals of the variables used against the standardized predicted values. If there was doubt with respect to violation of assumptions regarding distribution of residuals, we carried out a Mann-Whitney test comparing the 2 groups regarding the average of the measurements. Differences between both groups (AEC vs. AEC plus BEC) for the secondary outcome measures were analyzed by one-way ANOVA to correct for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software version 17.0.

Results

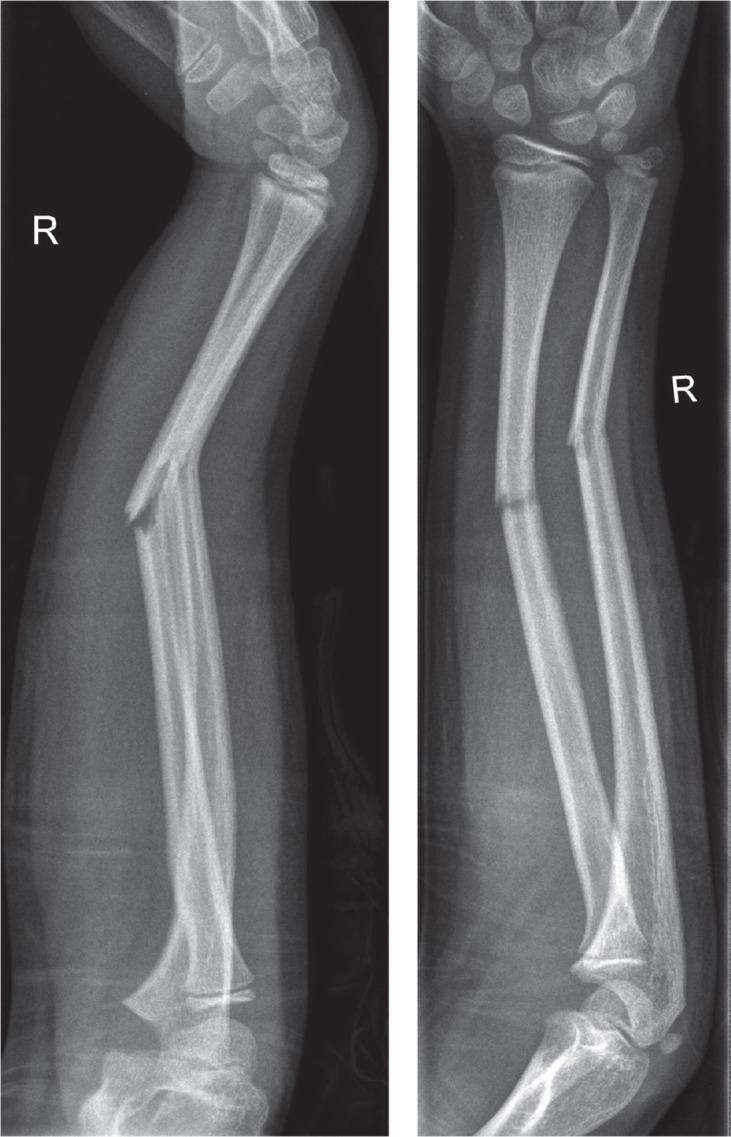

Between January 2006 and August 2010, 127 children were included in the study. 62 children were randomized to 6 weeks of AEC and 65 children were randomized to 3 weeks of AEC followed by 3 weeks of BEC (Figure 2). Despite the randomization, there was a substantial difference in age at the time of fracture, dominant arm fractured, and fracture type of the radius (Table 2). For this reason, the statistical analyses were corrected for these baseline variables.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of enrollment in the study.

n: number of children;

AEC: above-elbow cast;

BEC: below-elbow cast;

First: first examination;

Final: final examination;

+ : examined;

– : not examined.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study population. Unless otherwise stated, values are percentages

| Total | AEC | AEC + BEC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children | 127 | 62 | 65 |

| Mean (SD) age at time of fracture, years | 7.9 (3.2) | 8.7 (3.3) | 7.1 (2.9) |

| Male sex | 69 | 69 | 68 |

| Dominant arm fractured | 38 | 24 | 52 |

| Fracture type, radius | |||

| Greenstick | 46 | 34 | 58 |

| Complete | 54 | 66 | 42 |

| Mean (SD) location of fracture of radius a | 49 | 50 (13) | 49 (14) |

| Fracture type, ulna | |||

| Greenstick | 55 | 48 | 63 |

| Complete | 45 | 53 | 38 |

| Mean (SD) location of fracture of ulna a | 37 | 39 (13) | 35 (10) |

The location of the fracture was calculated by dividing the distance of the fracture to the wrist by the length of the bone.

AEC: above-elbow cast; BEC: below-elbow cast.

Fractures were reduced in the operating room in 68% of the children in the AEC group and in 70% of the children in the other group (AEC and BEC). The remaining fractures were reduced at the emergency department. The follow-up rate was 98%, with a mean follow-up time of 6.9 (4.7–12.9) months.

At 6-month follow-up, the mean limitation of pronation and supination was 18 degrees (95% CI: 0–50) for children treated with AEC, and 11 degrees (CI: 0–34) for children treated with AEC and BEC (p = 0.05). With and without adjustment for unbalanced covariates, no significant differences in primary outcome were found (Table 3).

Table 3.

Data on limitation of pronation and supination of the fractured arm. The data are percentagesa

| AEC | AEC + BEC | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 months after fracture | ||

| None | 7 | 13 |

| 1-10 | 20 | 31 |

| 11-20 | 25 | 20 |

| 21-30 | 15 | 8 |

| >31 degrees | 32 | 28 |

| Mean limitation (95% CI) | 28 (0–72) | 21 (0–57) |

| 6 months after fracture | ||

| None | 21 | 33 |

| 1–10 | 20 | 28 |

| 11–20 | 30 | 22 |

| 21–30 | 12 | 11 |

| > 31 degrees | 18 | 6 |

| Mean limitation (95% CI) | 18 (0–50) | 11 (0–34) |

With and without adjustment for unbalanced covariates, no significant differences were found.

AEC: above-elbow cast. BEC: below-elbow cast.

Using the grading system for limitation of pronation and supination (Daruwalla 1979), the results in the AEC-alone group were excellent in 21%, good in 38%, fair in 26%, and poor in 15%. In the group treated with AEC and BEC, the results were excellent in 33%, good in 37%, fair in 27%, and poor in 3%. Similar results were found using the modified grading system (Price et al. 1990). In the AEC group, the results were excellent in 33%, good in 42%, and fair in 25%. In the group treated with AEC and BEC, the results were excellent in 48%, good in 30%, fair in 20%, and poor in 2%.

The secondary outcome measures showed a higher VAS for comfort in the group of children treated with AEC and BEC (p < 0.001) (Table 4, see supplementary data). The questionnaire (Webb et al. 2006), which evaluated difficulties during the period of cast, gave similar results between the 2 groups.

There were 32 complications in 27 children treated with AEC and 25 complications in 23 children treated with AEC and BEC (Table 5). Most complications consisted of fracture re-displacement. Almost half of all re-displacements occurred in the group with reduction of the fracture in the emergency department, and all re-displacements occurred during the first 3 weeks. 9 of 43 re-displaced fractures were reduced again and treated after reduction with cast in 4 children, and with intramedullary nails and cast in 5 children. In 34 children, the re-displacement of the fracture was accepted. Furthermore, greenstick and complete fractures showed a similar rate of re-displacement.

Table 5.

Data on complications.Values are numbers of complicationsa

| AEC | AEC + BEC | |

|---|---|---|

| Displacement during cast | 23 | 20 |

| Refracture | 5 | 3 |

| Transient neuropraxia | 2 | 2 |

| Excoriation elbow crease | 1 | – |

| Nonunion | 1 | – |

| Total complications | 32 | 25 |

No significant difference was found between the 2 groups.

AEC: above-elbow cast; BEC: below-elbow cast.

At final follow-up, 23 children (12 of whom were aged ≥ 10 years) developed a malunion as defined by our primary reduction criteria (Table 6, see supplementary data). Although all 23 fractures showed re-displacement in cast, 3 were reduced a second time. The malunion was localized in the proximal half of the diaphysis of the radius and of the ulna in 15 and 3 children, respectively. Of the 23 children with a malunion, 7 regained almost full pronation and supination while 8 children suffered from a limitation of ≥ 31 degrees.

Discussion

We found that in the treatment of reduced stable diaphyseal both-bone forearm fractures in children, conversion from AEC to BEC was safe 3 weeks after the initial trauma. Limitation in flexion and extension of the elbow did not occur in either of the groups.

We found a limitation of pronation and supination of ≥ 30 degrees at final follow-up in 15 of 127 children, 8 of whom also suffered a radiographic malunion. 6 children with a radiographic malunion at final follow-up showed no limitation of pronation and supination. These findings demonstrate that limitation of pronation and supination is caused by malunion and contractures, as previously stated by other authors (Tynan et al. 2000, Weinberg et al. 2001, Dumont et al. 2002,Yasutomi et al. 2002, van Geenen and Besselaar 2007, Jupiter et al. 2009). The idea of contractures of injured soft tissue being a cause of limitation of pronation and supination was supported by a trend of better forearm rotation in the BEC group, in which children could rotate the forearm early to prevent contractures.

Compared with previous studies, limitation of pronation and supination was relatively high in our children. Using the grading system (Daruwalla 1979), we found that 21% (AEC) and 33% (AEC and BEC) had excellent results, whereas other authors have found excellent results in 44–100% of such children (Daruwalla 1979, Kay et al. 1986, Price et al. 1990, Jones and Weiner 1999, Bochang et al. 2005, Boero et al. 2007). The modified grading system (Price et al. 1990) resulted in 33% and 48% excellent results in our 2 groups, as compared to 82% in another study (Price et al. 1990). Our prospective analysis, inclusion of only the more severe both-bone forearm fractures, and the high percentage of malunions may have been responsible for our less favorable results.

Previous studies have found a re-displacement rate of 7–27% in non-operatively treated forearm fractures, whereas we found a rate of 34% (Monga et al. 2010, Kay et al. 1986, Voto et al. 1990, Chan et al. 1997, Jones and Weiner 1999, Bochang et al. 2005, Schmittenbecher 2005). This higher rate of re-displacement might be explained by our strict malunion criteria, the prospective follow-up with scheduled radiographs, our test for stability, and the type of cast (non-circumferential cast applied directly after reduction). Although BEC allows free movement of the elbow, in our study conversion to BEC after 3 weeks did not cause re-displacement of fractures. In our patients, all re-displacements occurred in the AEC group during the first 3 weeks of treatment.

In the statistical analysis, we were aware that strict correction for multiple testing was not necessary because of the evaluation of predefined hypotheses. However, we chose a conservative method to test the secondary outcome parameters. In addition, we also tested the secondary outcome without correction for multiple testing (using a p-value of 0.05), and even then no differences were found between groups.

Our study had several limitations. First, several fractures were reduced at the emergency department instead of in the operating room. The slightly higher rate of re-displacement in fractures reduced at the emergency department (42% vs. 30%) led us to suspect that testing of fracture stability without anesthesia and fluoroscopy is less optimal. Fortunately, there was an equal distribution of fractures reduced in the emergency room in the 2 groups, and this study investigated treatment modalities after reduction.

Secondly, not all re-displaced fractures were reduced following our study protocol. This was probably due to the expectation of correction of the malunion by growth, and the reluctance of the surgeon to propose a second reduction in view of the effect on the child.

Thirdly, the outcome of the test for stability after reduction was a subjective opinion of the treating physician. No tests for stability of fractures are objective, and the test used was the only one to appear in literature (Meier et al. 2004).

The final limitation was our (short) period of follow-up in this young population with a capacity for correction by growth. Nevertheless, these diaphyseal fractures (especially in older children) show less correction than distal metaphyseal fractures in younger children.

In summary, our results suggest that reduced stable diaphyseal both-bone forearm fractures in children can be safely treated by 3 weeks of above-elbow cast and 3 weeks of below-elbow cast. Re-displacement of the fracture might be identified early by radiography at set times.

Acknowledgments

JWC, JHA, CPV, and JANV were involved in the study design. JHA, LUB, CPV, MRV, RMB, and AJHK supervised the inclusion of children. JWC examined all the children. Statistical analysis was done by MR and JWC, and LUB provided the radiographic measurements. All the authors participated in writing and editing of the manuscript.

The corresponding author received a grant from the Anna Foundation/ NOREF, the Netherlands. The Anna Foundation/ NOREF took no part in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary data

Tables 4 and 6 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 5997.

References

- Arnould C, Penta M, Renders A, Thonnard JL. ABILHAND-Kids: a measure of manual ability in children with cerebral palsy . Neurology. 2004;63(6):1045–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000138423.77640.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar AR, Roberts JA. Treatment of unstable fractures of the forearm in children. Is plating of a single bone adequate? . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001;83(2):253–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b2.10955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochang C, Jie Y, Zhigang W, Weigl D, Bar-On E, Katz K. Immobilisation of forearm fractures in children: extended versus flexed elbow . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005;87(7):994–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boero S, Michelis MB, Calevo MG, Stella M. Multiple forearm diaphyseal fracture: reduction and plaster cast control at the end of growth . Int Orthop. 2007;31(6):807–10. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CF, Meads BM, Nicol RO. Remanipulation of forearm fractures in children . N Z Med J. 1997;110(1047):249–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaris J, van der Linden M, Selles R, Coene N, Allema JH, Verhaar J. Pronation and supination after forearm fractures in children: Reliability of visual estimation and conventional goniometry measurement . Injury (Comparative Study) 2010;41(6):643–6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daruwalla JS. A study of radioulnar movements following fractures of the forearm in children . Clin Orthop. 1979;(139):114–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont CE, Thalmann R, Macy JC. The effect of rotational malunion of the radius and the ulna on supination and pronation . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002;84(7):1070–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b7.12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogstrom H, Nilsson BE, Willner S. Correction with growth following diaphyseal forearm fracture . Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(3):299–303. doi: 10.3109/17453677608991994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, Weiner DS. The management of forearm fractures in children: a plea for conservatism . J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19(6):811–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupiter JB, Fernandez DL, Levin LS, Wysocki RW. Reconstruction of posttraumatic disorders of the forearm . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009;91(11):2730–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200911000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S, Smith C, Oppenheim WL. Both-bone midshaft forearm fractures in children . J Pediatr Orthop. 1986;6(3):306–10. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier R, Prommersberger KJ, van Griensven M, Lanz U. Surgical correction of deformities of the distal radius due to fractures in pediatric patients . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monga P, Raghupathy A, Courtman NH. Factors affecting remanipulation in paediatric forearm fractures . J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19(2):181–7. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e3283314646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers GJ, Gibbons PJ, Glithero PR. Nancy nailing of diaphyseal forearm fractures. Single bone fixation for fractures of both bones . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004;86(4):581–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimark A, Kossoff J, Leach RE. The disparate diameter. A sign of rotational deformity in fractures . J Can Assoc Radiol. 1983;34(1):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson BE, Obrant K. The range of motion following fracture of the shaft of the forearm in children . Acta Orthop Scand. 1977;48(6):600–2. doi: 10.3109/17453677708994804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CT, Scott DS, Kurzner ME, Flynn JC. Malunited forearm fractures in children . J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10(6):705–12. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittenbecher PP. State-of-the-art treatment of forearm shaft fractures . Injury (Suppl 1) 2005. 36:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynan MC, Fornalski S, McMahon PJ, Utkan A, Green SA, Lee TQ. The effects of ulnar axial malalignment on supination and pronation . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000;82(12):1726–31. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Geenen RC, Besselaar PP. Outcome after corrective osteotomy for malunited fractures of the forearm sustained in childhood . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007;89(2):236–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.18208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voto SJ, Weiner DS, Leighley B. Redisplacement after closed reduction of forearm fractures in children . J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10(1):79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb GR, Galpin RD, Armstrong DG. Comparison of short and long arm plaster casts for displaced fractures in the distal third of the forearm in children . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(1):9–17. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg AM, Pietsch IT, Krefft M, Pape HC, van Griensven M, Helm B, et al. Pronation and supination of the forearm. With special reference to the humero-ulnar articulation . Unfallchirurg. 2001;104(5):404–9. doi: 10.1007/s001130050750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasutomi T, Nakatsuchi Y, Koike H, Uchiyama S. Mechanism of limitation of pronation/supination of the forearm in geometric models of deformities of the forearm bones . Clin Biomech (Bristol. Avon) 2002;17(6):456–63. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(02)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.