Abstract

Background

Increased infection risk in inflammatory rheumatic diseases may be due to inflammation or immunosuppressive treatment. The influence of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors on the risk of developing surgical site infections (SSIs) is not fully known. We compared the incidence of SSI after elective orthopedic surgery or hand surgery in patients with a rheumatic disease when TNF inhibitors were continued or discontinued perioperatively.

Patients and methods

We included 1,551 patients admitted for elective orthopedic surgery or hand surgery between January 1, 2003 and September 30, 2009. Patient demographic data, previous and current treatment, and factors related to disease severity were collected. Surgical procedures were grouped as hand surgery, foot surgery, implant-related surgery, and other surgery. Infections were recorded and defined according to the 1992 Centers for Disease Control definitions for SSI. In 2003–2005, TNF inhibitors were discontinued perioperatively (group A) but not during 2006–2009 (group B).

Results

In group A, there were 28 cases of infection in 870 procedures (3.2%) and in group B, there were 35 infections in 681 procedures (5.1%) (p = < 0.05). Only foot surgery had significantly more SSIs in group B, with very low rates in group A. In multivariable analysis with groups A and B merged, only age was predictive of SSI in a statistically significant manner.

Interpretation

Overall, the SSI rates were higher after abolishing the discontinuation of anti-TNF perioperatively, possibly due to unusually low rates in the comparator group. None of the medical treatments analyzed, e.g. methotrexate or TNF inhibitors, were significant risk factors for SSI. Continuation of TNF blockade perioperatively remains a routine at our center.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are at increased risk of developing infections (Doran et al. 2002). Age, co-morbidities, and a range of disease-related factors have been found to predict infection (Doran et al. 2002). TNF (tumor necrosis factor) inhibitors have been used for RA since 1997 (Salliot et al. 2007), and today they are also used for ankylosing spondylitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease (Feldmann and Maini 2002). TNF inhibitors are thought to increase the risk of developing infections, and there might be a higher frequency of skin and soft tissue infections compared to treatment with other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (Dixon et al. 2006). Meta-analyses and observational studies have shown that treatment with TNF antagonists is associated with an increased risk of developing serious infections (Listing et al. 2005, Bongartz et al. 2006, Leombruno et al. 2009) and hospitalization with infections (Askling et al. 2007). Other studies, however, have shown contrary results (Dixon et al. 2006). Prospective data on perioperative infection risk have not shown an increased risk with methotrexate (MTX), and it is generally not withheld in the perioperative period from patients who benefit from it (Grennan et al. 2001, Scanzello et al. 2006). Data on the effect of TNF blockade, and of perioperative continuation or withholding of this treatment, on the risk of surgical site infection (SSI) is conflicting (Bibbo and Goldberg 2004, Talwalkar et al. 2005, Wendling et al. 2005, Giles 2006, den Broeder et al. 2007, Ruyssen-Witrand et al. 2007, Gilson et al. 2010, Momohara et al. 2011, Suzuki et al. 2011) .

The incidence of postoperative infections is 0.5–6.0% depending on the center, the type of surgery, and the site of surgery (Bongartz 2007). Rheumatic patients, however, are at greater risk of developing postoperative infection (Poss et al. 1984, Bongartz et al. 2008, Schrama et al. 2010). The British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register has shown a doubled risk of septic arthritis generally in patients with RA and anti-TNF therapy, compared to RA patients treated with non-biological DMARDs (Galloway et al. 2011). Although there is no clear evidence of biological DMARDs causing more surgical infections, rheumatological organizations of many countries recommend that they should be withheld perioperatively (Pham et al. 2005, den Broeder et al. 2007, Saag et al. 2008, Ding et al. 2010).

On Jan 1, 2006, new local guidelines were introduced at the Departments of Rheumatology and Orthopedics at Lund University Hospital, stating that TNF inhibitors should not be discontinued perioperatively. We have now compared the incidence of SSI after elective orthopedic surgery or hand surgery in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases in 2003–2005, when TNF inhibitors were discontinued perioperatively, with that after Jan 1, 2006.

Subjects and methods

Patients

Lund University Hospital recruits inflammatory arthritis patients from primary and secondary care, but with occasional regional tertiary and national quaternary referrals. There are approximately 300 elective orthopedic and hand surgery procedures per year in rheumatic patients. About half of them are admitted to the rheumatic ward and half to the orthopedic ward.

All rheumatic patients admitted to the Departments of Rheumatology and Orthopedics, Lund University Hospital, undergoing elective orthopedic or hand surgery between January 1, 2003 and September 30, 2009 were enrolled in this study. The patients admitted to the rheumatic ward were examined 1–4 weeks before surgery (baseline) and the information was entered into a database. The data collected at baseline included patient demographics, diagnosis, disease duration, and current and previous anti-rheumatic therapy. Swollen and tender joint count, the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) (Ekdahl et al. 1988), patients visual analog scale (VAS) for global health and pain, the evaluators global assessment of disease activity (5-grade Likert scale), ESR, and C-reactive protein (CRP) values were recorded, enabling calculation of disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) (www.das28.nl 2011) and clinical disease activity index (CDAI) (Aletaha and Smolen 2005). Data for the patients admitted to the orthopedic ward were collected from the medical records and included demographics, diagnosis, and current anti-rheumatic therapy. All patients were followed with a view to having 6 months of follow-up, and postoperative complications were recorded, especially infections.

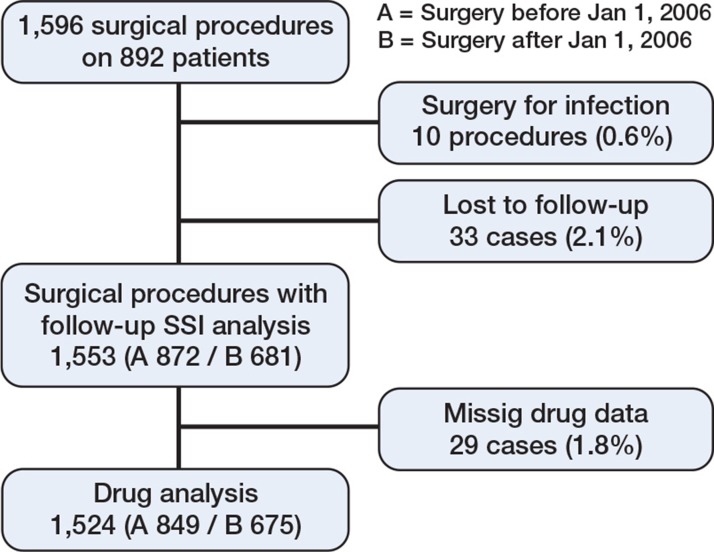

Infections were classified as superficial, deep, or organ-/space-related SSI, according to the 1992 US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definitions of nosocomial SSI. The infection should have occurred within 30 days of surgery (1 year with foreign material) and there should have been at least 1 of: (1) purulent drainage, (2) positive culture (superficial) or evidence of infection found by direct, histological, surgical, or radiological examination (deep), (3) requirement of reopening of the surgical site, or (4) SSI diagnosed by the surgeon or attending physician (Horan et al. 1992). The infection cases were controlled and classified according to these definitions by one of the authors (EB). Medical records for patients lacking postoperative follow-up in Lund were scrutinized for infectious complications, and patients without medical follow-up were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of the process of collecting patients for analysis.

Surgical procedures

The procedures were divided into 4 groups depending on the type of surgery: foot, hand, implant, and other. In the foot group we included all surgeries except ankle prostheses, whereas implants (mainly silicone interposition) in the hand were included in the hand group. The implant group comprised procedures where prosthetic material was implanted in a great/medium-sized joint, mostly with cement, irrespective of whether it was revision arthroplasty or a primary procedure. The “other” group included mainly arthrodesis, synovectomy, and soft tissue procedures at sites other than the hand or foot. Internal fixation, with screws for example, was not regarded as implant surgery. All procedures were, however, analyzed according to the same protocol regarding postoperative follow-up and development of infections.

In arthroplasty of the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder, and elbow, 3 doses of Cloxacillin (2 g intravenously or 600 mg Clindamycin in allergic subjects) were given, the first dose was aimed to be given 30 min before surgery. In foot or ankle arthrodesis, osteotomy, and other procedures, 1 dose was aimed to be given 30 min before surgery.

Study design

This was an observational, non-randomized, single-center study. In 2003, a clinical protocol for characterization of patients undergoing orthopedic surgery and hand surgery was established at the Department of Rheumatology in Lund. This provided an opportunity to observe the effects of not withholding TNF inhibitors when the guidelines for treatment with TNF inhibitors where changed on January 1, 2006. In 2003–2005, the anti-TNF agents infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab were discontinued preoperatively for 8, 1, and 4 weeks, respectively, and reintroduced 1 week after surgery if there was no sign of infection. After January 1, 2006, following local ethical committee approval (no. 229/2006), the TNF inhibitors were continued at stable dosage before and during surgery.

Statistics

Group A consisted of patients with surgery in 2003–2005 and group B consisted of those operated between January 1, 2006 and September 30, 2009. Multiple surgical interventions performed simultaneously at different joint locations (e.g. joint replacement in both hips) on the same patient were treated as individual procedures in the analysis, while all hand/foot surgery was treated as one procedure regardless of different surgical components, as long as only one hand or foot was operated on. In patients with more than one operation, subsequent procedures were weighted using the generalized estimating equation to handle correlated data (Liang et al. 1986, Prentice 1988). All p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Differences in infection rates between the groups were analyzed using chi-squared test and Fishers exact test as appropriate. Binary, logistic regression models were used to investigate potential risk factors for postoperative SSI, with all SSIs (superficial and deep) being the dependent variable. Age at surgery, disease duration at surgery, ongoing treatment with prednisolone (yes/no), MTX (yes/no), biological DMARDs (yes/no), HAQ, and CDAI were chosen a priori for the multivariable analysis. Other variables tested univariably (cross-tables for ordinal and Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables) included sex, ESR and CRP, ongoing DMARDs other than MTX, TNF inhibitors, and the combination of all biological DMARDs and MTX. Only a priori selected variables with indication of differences between groups A and B were entered in the regression model. Furthermore, groups A and B were combined in the model due to low event rates. Analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics 17.0 for Windows and SAS for multiple correlation weighting (SAS Institute 2011).

Results

1,596 elective orthopedic and hand procedures were performed on 892 patients. 10 procedures in 9 patients had infection as indication for surgery, and 33 procedures lacked follow-up—24 in group A and 9 in group B—and they were excluded from the SSI analyses. 29 cases lacking drug data were excluded from the drug analyses. Thus, 1,553 procedures were included in the main analysis of SSI and 1,524 were included in the drug analyses (Figure 1). In the period 2003–2005 (group A), when TNF inhibitors were discontinued before surgery, 872 procedures were performed. In the period 2006–2009 (group B), with continuation of anti-TNF treatment, 681 procedures were executed. In group A, there were 270 procedures (32%) on patients with TNF inhibitors and the corresponding number in group B was 243 (36%). Mean follow-up time was 5.3 (SD 4.5) months and the median was 8.5 months.

Apart from the fact that there were more patients on MTX and anti-TNF agents and that there was longer disease duration before surgery in group B, there were no major differences between the groups. RA was the diagnosis for around two-thirds of patients in each group (Table 1). The types of surgical procedures are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, treatment of subjects and frequency of diagnoses in the 2 groups. Values are number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. Statistics for dosage are presented as mean (SD) mg/week

| Parameter | Group A (n = 872) |

Valid n | Group B (n = 681) |

Valid n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 483 (55) | 509 (75) | ||

| Age at surgery, mean (SD) | 55 (18) | 59 (15) | ||

| Disease duration at surgery, mean (SD) in years | 19.5 (12) | 341 | 21.5 (13) | 587 |

| Mean HAQ (health assessment questionnaire) (0–3) | 1.3 (0.7) | 324 | 1.3 (0.7) | 511 |

| Mean CDAI (clinical disease activity index) (0–100) | 14 (9.0) | 302 | 13 (8.7) | 528 |

| ESR, mean (SD), mm/h | 27 (22) | 305 | 25 (19) | 469 |

| CRP, mean (SD), mg/L | 19 (29) | 448 | 13 (21) | 602 |

| Previous biological DMARD | 84 (10) | 106 (16) | ||

| Length of treatment with the current biological DMARD before surgery, mean (SD), years | 2.5 (1.9) | 247 | 3.2 (2.6) | 249 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Prednisolone | 368 (46) | 848 | 307 (47) | 675 |

| Dosage prednisolone for treated patient | 41 (32) | 385 | 42 (25) | 318 |

| Methotrexate | 364 (45) | 849 | 332 (51) | 675 |

| Dosage of methotrexate for treated patient | 14.6 (5.4) | 390 | 15.6 (5.2) | 340 |

| DMARDs other than methotrexate | 207 (26) | 849 | 140 (21) | 675 |

| Biological DMARDs a | 256 (32) | 849 | 252 (38) | 675 |

| TNF inhibitor | 249 (31) | 849 | 236 (36) | 675 |

| Dosage of infliximab for treated patient | 58.7 (71) | 58 | 56.3 (29) | 40 |

| Dosage of etanercept for treated patient | 44.8 (14) | 171 | 48.1 (11) | 136 |

| Dosage of adalimumab for treated patient | 19.6 (8.9) | 41 | 23.0 (7.8) | 66 |

| Biological DMARDs + methotrexate | 145 (18) | 847 | 147 (22) | 675 |

| Diagnosis b | ||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 581 (67) | 448 (66) | ||

| Spondyloarthritis incl. ankylosing spondylitis | 32 (4) | 24 (4) | ||

| Psoriatic arthritis | 32 (4) | 35 (5) | ||

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 133 (15) | 64 (9) | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 13 (2) | 20 (3) | ||

| Other rheumatic diagnosis | 80 (9) | 88 (13) | ||

In group A, 6 patients were treated with anakinra, and 1 with rituximab. In group B, 11 patients were treated with rituximab, 4 with anakinra, 1 with abatacept, and 1 with tocilizumab.

Diagnosis was missing in 1 patient in group A and in 2 patients in group B.

Table 2.

Surgical procedures according to groups

| Foot | Hand | Implant | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (total) | 214 a | 166 b | 255 c | 46 d |

| Prosthesis | 255 | |||

| Arthrodesis | 110 | 66 | 4 | |

| Synovectomy | 32 | 21 | 5 | |

| Resection | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Forefoot reconstruction | 44 | |||

| Miscellaneous | 42 | 81 | 32 | |

| Group B (total) | 316 e | 79 f | 343 g | 134 h |

| Prosthesis | 343 | |||

| Arthrodesis | 152 | 31 | 6 | |

| Synovectomy | 1 | 5 | 24 | |

| Resection | 30 | 1 | 14 | |

| Forefoot reconstruction | 35 | |||

| Miscellaneous | 98 | 42 | 90 |

67 multiple joints and 122 other implants.

27 multiple joints and 98 other implants.

6 multiple joints and 54 revision arthroplasties.

9 multiple joints and 9 other implants.

135 multiple joints and 184 other implants.

34 multiple joints and 48 other implants.

34 multiple joints and 77 revision arthroplasties.

23 multiple joints and 24 other implants.

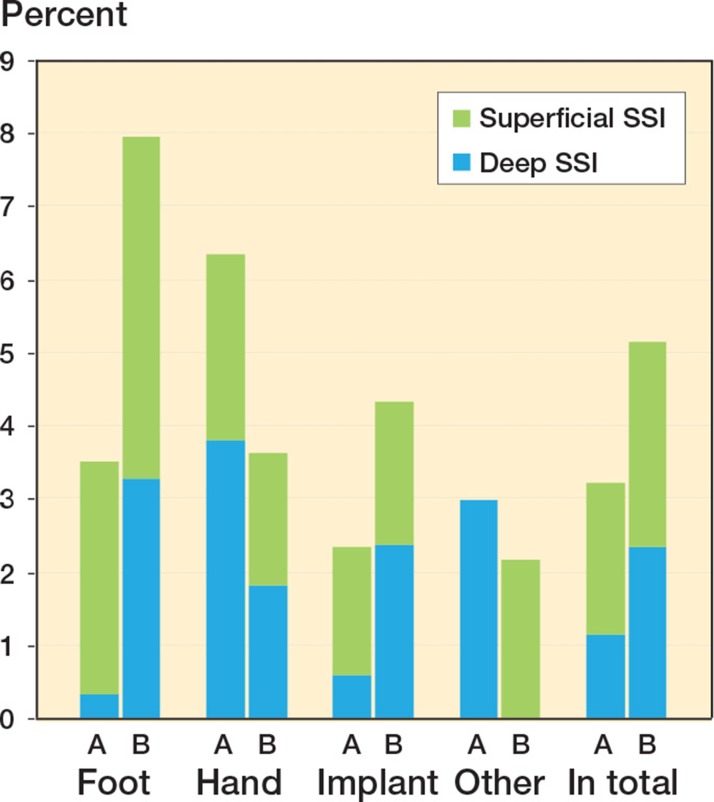

The total SSI rates, both superficial and deep, were 25 (3.0%) in group A and 35 (5.3%) in group B (Figure 2). Only 1 patient had an organ/space-related SSI, septicemia 2 weeks after osteotomy of the ankle. When comparing the infection rates within the subgroups foot, hand, implant, and other using univariable analysis, the difference only reached significance in the foot group (Figure 2 and Table 3). There was no significant association between infection rates and medical treatment; however, treatment with MTX and also treatment with non-biological DMARDs other than MTX showed a tendency to increase the risk of SSI in group B when tested univariably (Table 4).

Figure 2.

All surgical site infections (SSIs) according to group and type of surgery, showing the proportion of superficial and deep infections.

Table 3.

The total number of infections divided by type of surgery. Values are number (percentage, according to type of surgery). The p-values refer to infection rate within each surgery group

| Type of surgery | Group A | Group B | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foot (n A 214, B 314) | 11 (3.5) | 17 (7.9) | 0.03 |

| deep infection | 1 (0.3) | 7 (3.3) | 0.01 a |

| Hand (n A 79, B 166) | 5 (6.3) | 6 (3.6) | 0.3 a |

| deep infection | 3 (3.8) | 3 (1.8) | 0.4 a |

| Implant (n A 343, B 255) | 8 (2.3) c | 11 (4.3) c | 0.2 |

| deep infection | 2 (0.6) c | 6 (2.4) b | 0.08 a |

| Other (n A 134, B 46) | 4 (3.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1.0 a |

| deep infection | 4 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.6 a |

Fisher’s exact test.

1 revision arthroplasty.

2 revision arthroplasties.

Table 4.

The total number of infections in the different medication groups. Values are number (percentage). The p-values compare infection rate with and without each treatment in groups A and B, respectively. A patient could be treated with multiple drugs

| Medication | With treatment | Without | p-value (χ2 test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | |||

| Prednisolone | 14 (3.6) | 14 (2.9) | 0.5 |

| Methotrexate | 11 (2.8) | 17 (3.5) | 0.6 |

| DMARDs other than methotrexate | 8 (3.6) | 20 (3.0) | 0.7 |

| All biological DMARDs | 12 (4.3) | 16 (2.7) | 0.2 |

| Anti-TNF | 11 (4.1) | 17 (2.8) | 0.3 |

| All biological DMARDs + methotrexate | 5 (3.4) | 23 (3.2) | 0.8 a |

| Group B | |||

| Prednisolone | 16 (5.2) | 19 (5.4) | 1.0 |

| Methotrexate | 22 (6.6) | 13 (4.0) | 0.07 |

| DMARDs other than methotrexate | 5 (3.6) | 30 (5.8) | 0.07 |

| All biological DMARDs | 10 (4.0) | 25 (6.2) | 0.3 |

| Anti-TNF | 9 (3.8) | 26 (6.2) | 0.3 |

| All biological DMARDs + methotrexate | 6 (4.1) | 29 (5.5) | 0.3 |

Fisher’s exact test.

In group A, 17 cultures were performed and all of these were positive. In group B, 26 cultures were performed and 21 of these (80%) were positive. The most frequent pathogen found was S. aureus; it was found in over half of the cases.

Significant predictors of SSI using univariable analysis were: age at surgery and disease duration at surgery in group A, and in groups A and B combined. These variables were combined in a binary, logistic regression model together with treatment options to form a detailed analysis of factors influencing the risk of SSI, combining groups A and B. When we included an interaction term between MTX and biological DMARDs in the regression model, the interaction effect of MTX and biological DMARDs had a lower multiplicative effect than expected. The expected odds ratio (OR) was about 6 and the observed OR was 0.21. Age at surgery, divided into strata of 5 years (OR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.03–1.32) reached statistical significance, but the different treatment options, including prednisolone, did not. Treatment with biological DMARDs per se was not a risk factor for infection in this analysis; nor were measures of disease activity (not significant in univariable analysis). Sensitivity analyses using uncorrected event weight per procedure in individual patients yielded an almost significant OR (0.61, 95% CI: 0.37–1.02; p = 0.06), whereas only using first procedure per patient did not (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.34–1.37; p = 0.3) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Regression models for SSI outcomea

| Model | Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Group A vs. group B | 0.68 (0.38–1.21) | 0.2 |

| Model 2 | Group A vs. group B | 0.85 (0.41–1.73) | 0.6 |

| Age b | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | 0.02 | |

| Disease duration b | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | 0.2 | |

| Model 3 | Group A vs. group B | 0.87 (0.42–1.77) | 0.7 |

| Age b | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | 0.02 | |

| Disease duration b | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) | 0.1 | |

| Methotrexate (yes) | 1.72 (0.84–3.51) | 0.1 | |

| Model 4 | Group A vs. group B | 0.86 (0.42–1.77) | 0.7 |

| Age b | 1.17 (1.03–1.34) | 0.02 | |

| Disease duration b | 1.08 (0.97–1.19) | 0.2 | |

| Biologic (yes) | 1.18 (0.57–2.44) | 0.6 | |

| Model 5 | Group A vs. group B | 0.87 (0.43–1.80) | 0.7 |

| Age b | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.03 | |

| Disease duration b | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.1 | |

| Biologic (yes) | 1.10 (0.51–2.35) | 0.8 | |

| Methotrexate (yes) | 1.71 (0.82–3.56) | 0.2 | |

| Model 6 | Model 5 + methotrexate*bio as interaction term | 0.21 (0.05–0.88) | 0.03 |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||

| No correlation correction for multiple surgical procedures in each individual Group A vs group B | 0.61 (0.37–1.02) | 0.06 | |

| Only first surgical procedure in each individual included Group A vs group B | 0.69 (0.34–1.37) | 0.3 | |

Models 1–6 use correlation correction for multiple surgical procedures in one individual. Model 6 studies interaction between methotrexate and biologic drugs. For explanation, see text.

Sensitivity analyses include non-correlation corrected models and only using first surgical procedure in one individual. Group A includes procedures performed before January 1, 2006 and group B includes those performed after this date.

per 5 years

Discussion

One main finding was that the SSI rate was increased in patients with inflammatory arthritis who continued treatment with TNF inhibitors perioperatively at elective hand and orthopedic surgery. However, this was caused by a remarkably low frequency of deep SSI after foot surgery in the comparator population (0.3% vs 3.3%), the reason for which remains the subject of speculation. The usual incidence of deep infections in foot surgery is estimated to be 3%, (U Rydholm 2010, personal communication), which is well in line with our findings in group B but contrasts with the results in group A. Otherwise, the infection risk was similar between the groups. Interestingly, perioperative medication could not be identified as a risk factor for either deep SSI or superficial SSI in the subanalysis.

Out of 10 studies on the influence of anti-TNF agents on SSI rates (Bibbo and Goldberg 2004, Talwalkar et al. 2005, Wendling et al. 2005, Giles et al. 2006, den Broeder et al. 2007, Ruyssen-Witrand et al. 2007, Gilson et al. 2010, Kawakami et al. 2010, Momohara et al. 2011, Suzuki et al. 2011), 1 small study did not show elevated infection rates in foot and ankle surgery (Bibbo and Goldberg 2004). 4 of the studies identified an increased risk of SSI during treatment with anti-TNF agents (Giles et al. 2006, Gilson et al. 2010, Kawakami et al. 2010, Suzuki et al. 2011). The studies mentioned were mostly underpowered to detect small differences in infection rates, they had different designs precluding head to head comparison, and the observational setting may have caused selection bias which could go in either direction. TNF inhibitors may have been prescribed to the patients with the most aggressive RA, and therefore in those who were most susceptible to infections, or physicians may have avoided using anti-TNF agents in cases with the highest infection risk.

Besides simplifying the perioperative routines, the introduction of our new local guidelines in 2006 was also an attempt to challenge the view that TNF inhibitors—given their important role in defense against bacterial infection—would elevate SSI rates in clinical practice. We cannot rule out this possibility, but our data lend little support for such a conclusion. There are few data in the literature on SSI risk in relation to TNF inhibitors, and some of them are conflicting. The almost universal policy of discontinuation of anti-TNF is thus based on the principle of prudence, and on expert opinion. On the other hand, MTX is generally considered to be harmless regarding SSI risk, and in most centers including ours, it is not discontinued before surgery. This practice is based on 1 unconfirmed randomized controlled trial (Grennan et al. 2001). According to our regression model, however, even though the ORs are modest, the combination of MTX and TNF blocker appears to protect against SSI, whereas MTX and possibly other DMARDs almost emerged as a risk factor in group B (Table 4).

Notwithstanding the study by Grennan et al. on MTX and risk of SSI, one could speculate that in some settings, MTX may contribute to risk of SSI to a greater extent than TNF inhibitors. We did not identify biological DMARDs to be a risk factor for SSI in the multivariable analysis, as has been suggested by previous studies (Giles et al. 2006, Gilson et al. 2010, Kawakami et al. 2010, Suzuki et al. 2011). Interestingly, the multivariable analysis did not support an expected potentiating effect of the combination of biological therapy and MTX in development of SSI, rather the contrary. The roles of conventional DMARDs and TNF inhibitors in contributing to SSI risk require further investigation.

Our finding of age as being a predictor of SSI is in line with the work of Doran et.al. (2002), but we could not identify treatment with prednisolone as a risk factor for development of SSI, as found in previous studies (Grennan et al. 2001, Salliot et al. 2007). High doses of prednisolone, which are often needed in a flare-up, e.g. after discontinuation of TNF inhibitors, have been suggested to be a risk factor for developing postoperative infection (Pappas and Giles 2008, Gilson et al. 2010). Our study patients were mostly on low, stable doses of prednisolone, but on the other hand we did not register postoperative flares and short-term increases in prednisolone dosage. However, measures of disease activity at baseline did not influence the risk of SSI.

The present study had limitations. Firstly, the low number of infectious events precluded subgroup analysis. The limited number of SSIs required combination of the 2 groups in the multivariable analysis. Secondly, multiple procedures were performed in some patients. Thus, patients with increased infection risk may have contributed with several infectious events. To compensate for these non-independent observations, we employed the generalized estimating equation to handle correlated data (Liang et al. 1986, Prentice 1988). In the sensitivity analysis, treating all procedures with equal weight, the SSI risk in group B tended to be overestimated, almost reaching statistical significance. This was not the case in the main analysis. Furthermore, analyses performed only on the first operation of every patient gave similar results (Table 5). Thirdly, we did not prospectively assemble information on previous SSI and co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus—factors that have previously been shown to be predictors of SSI (Hämäläinen et al. 1984, Grennan et al. 2001, Doran et al. 2002, den Broeder et al. 2007). Fourthly, one can speculate that our results with more infections in group B may have been due to secular trends. Rheumatologists may have become more comfortable with anti-TNF treatment, thereby starting treatment in more severely ill patients, which would result in an increasing number of infectious events. In our setting, however, more patients were started on treatment early in the course of their disease in 2006 than in previous years (Soderlin and Geborek 2008). Furthermore, the 1992 CDC definitions of nosocomial SSIs are not strict enough to provide sufficient guidance in the diagnostics of SSI, and they have not been validated for elective orthopedic surgery such as arthroplasty (Bongartz 2007). We nevertheless found them suitable for our study. Finally, our results may not be able to be extrapolated to strict RA populations, since we included various rheumatological diagnoses. However, the diagnoses were ascertained by rheumatology specialists. On the other hand, we have had the benefit of close patient follow-up and continuity in personnel and surgical routines such as perioperative use of antibiotics, ensuring almost complete follow-up. The 33 dropouts (2.1%) involved some patients of tertiary referral character and also a number of relatively minor surgical interventions not requiring regular long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, we have found higher total SSI rates in patients continuing anti-TNF treatment perioperatively than in those not continuing this treatment, possibly due to low frequency of SSI in the latter group. No medical treatments, including TNF inhibitors, were found to be significantly associated with SSI risk, but there tended to be an increased risk with methotrexate. In view of our findings and other evidence available, the routine of continuing anti-TNF treatment perioperatively is maintained at our center. Further research will be required to provide a proper basis for discontinuation of drugs in the context of elective orthopedic surgery and hand surgery in patients with rheumatic disease.

Acknowledgments

EB acquired the data, performed the statistical calculations, and drafted the manuscript. PG managed the database, suggested the statistical methodology, and helped revise the manuscript. AG conceived the study and helped revise the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We thank Jan-Åke Nilsson for help with the statistical work, Elna Haglund (research nurse) for help with data collection and Anna Stefansdottir (orthopedic surgeon) for valuable suggestions.

This study was funded by grants from Region Skåne, Lund University Hospital, the Faculty of Medicine at Lund University, the Österlund and Kock Foundations, the Swedish Rheumatism Association, and the King Gustav V 80-Year Birthday Foundation.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Aletaha D, Smolen J. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis . Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S100–8. (5 Suppl 39) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askling J, Fored MC, Brandt L, et al. Time-dependent increase in risk of hospitalisation with infection among Swedish RA patients treated with TNF antagonists . Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(10):1339–44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbo C, Goldberg JW. Infectious and healing complications after elective orthopaedic foot and ankle surgery during tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition therapy . Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(5):331–5. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongartz T, Elective orthopedic surgery and perioperative DMARD management: many questions, fewer answers, and some opinions . J Rheumatol. 2007;34(4):653–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trial . JAMA. 2006;295(19):2275–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.19.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Broeder A, Creemers M C W, Fransen J, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infections and other complications in elective surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with special attention for anti-tumor necrosis factor: a large retrospective study . J Rheumatol 2007. 34((4)):689–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T, Ledingham J, Luqmani R, et al. BSR and BHPR rheumatoid arthritis guidelines on safety of anti-TNF therapies . Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(11):2217–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq249a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WG, Watson K, Lunt M, et al. Rates of serious infection, including site-specific and bacterial intracellular infection, in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register . Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2368–76. doi: 10.1002/art.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, OFallon WM, Gabriel SE. Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2294–300. doi: 10.1002/art.10529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl C, Eberhardt K, Andersson SI, Svensson B. Assessing disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Use of a Swedish version of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire . Scand J Rheumatol. 1988;17(4):263–71. doi: 10.3109/03009748809098795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, Maini RN, Discovery of TNF-alpha as a therapeutic target in rheumatoid arthritis: preclinical and clinical studies . Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69(1):12–8. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, et al. Risk of septic arthritis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the effect of anti-TNF therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register . Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1810–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.152769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles JT, Bartlett SJ, Gelber AC, et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and risk of serious postoperative orthopedic infection in rheumatoid arthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(2):333–7. doi: 10.1002/art.21841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson M, Gossec L, Mariette X, et al. Risk factors for total joint arthroplasty infection in patients receiving tumor necrosis factor alpha-blockers: a case-control study . Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(4):R145. doi: 10.1186/ar3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grennan DM, Gray J, Loudon J, Fear S. Methotrexate and early postoperative complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery . Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(3):214–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(10):606–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hämäläinen M, Raunio P, Von Essen R. Postoperative wound infection in rheumatoid arthritis surgery . Clin Rheumatol. 1984;3:329–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02032339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Katsunori I, Kawamura K, et al. Complications and features after joint surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tumour necrosis factor-{alpha} blockers: perioperative interruption of tumour necrosis factor-{alpha} blockers decreases complications? . Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(2):341–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leombruno JP, Einarson TR, Keystone EC. The safety of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatments in rheumatoid arthritis: meta and exposure-adjusted pooled analyses of serious adverse events . Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1136–45. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Kung-Yee Liang; Scott L . Zeger. Biometrika. 1986;73(1) [Google Scholar]

- Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents . Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3403–12. doi: 10.1002/art.21386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momohara S, Kawakami K, Iwamoto T, et al. Prosthetic joint infection after total hip or knee arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs . Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21(5):469–75. doi: 10.1007/s10165-011-0423-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas DA, Giles JT. Do antitumor necrosis factor agents increase the risk of postoperative orthopedic infections? . Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(4):450–6. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282fcc345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T, Claudepierre P, Deprez X, et al. Anti-TNF alpha therapy and safety monitoring. Clinical tool guide elaborated by the Club Rhumatismes et Inflammations (CRI), section of the French Society of Rheumatology (Societe Francaise de Rhumatologie, SFR) . Joint Bone Spine (Suppl 1) 2005;72:S1–58. doi: 10.1016/s1169-8330(05)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss R, Thornhill TS, Ewald FC, Thomas WH, Batte NJ, Sledge CB. Factors influencing the incidence and outcome of infection following total joint arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 1984;(182):117–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice RL. Correlated binary regression with cCovariates specific to each binary observation . Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1033–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruyssen-Witrand A, Gossec L, Salliot C, et al. Complication rates of 127 surgical procedures performed in rheumatic patients receiving tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers . Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(3):430–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salliot C, Gossec L, Ruyssen-Witrand A, et al. Infections during tumour necrosis factor-alpha blocker therapy for rheumatic diseases in daily practice: a systematic retrospective study of 709 patients . Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(2):327–34. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc., Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) to handle correlated data. PROC GENMOD in the SAS System 9.3. (Cary, NC, USA) 2011

- Scanzello CR, Figgie MP, Nestor BJ, Goodman SM. Perioperative management of medications used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis . HSS J. 2006;2(2):141–7. doi: 10.1007/s11420-006-9012-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrama JC, Espehaug B, Hallan G, et al. Risk of revision for infection in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with osteoarthritis: a prospective, population-based study on 108,786 hip and knee joint arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register . Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(4):l473–9. doi: 10.1002/acr.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlin MK, Geborek P. Changing pattern in the prescription of biological treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. A 7-year follow-up of 1839 patients in Southern Sweden . Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:37–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.070714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Nishida K, Soen S, et al. Risk of postoperative complications in rheumatoid arthritis relevant to treatment with biologic agents: a report from the Committee on Arthritis of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association . J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(6):778–84. doi: 10.1007/s00776-011-0142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwalkar SC, Grennan DM, Gray J, Johnson P, Hayton MJ. Tumour necrosis factor alpha antagonists and early postoperative complications in patients with inflammatory joint disease undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery . Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(4):650–1. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.028365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling D, Balblanc J-C, Brousse A, et al. Surgery in patients receiving anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: an observational study on 50 surgical procedures . Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(9):1378–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.037762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]