Abstract

The Mucha-Habermann disease is an inflammatory disease of the skin and is a variant of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. We describe the case of a 64-years-old woman who was admitted for erysipelas of the face. Despite treatment, evolution was marked by the appearance of a necrotising ulcerative area in the centre of the erysipelas associated with local oedema and headache. A skin biopsy revealed a pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Corticosteroids led to a rapid stabilisation of lesions, and after 6 months the patient shows only a small area of frontal hypopigmentation. The aetiology remains uncertain. There is no established standard treatment. We would like to draw attention of the medical and surgical specialists to this rare disease. The diagnosis should be considered in a necrotic lesion associated with rapid expansion of systemic and peripheral cutaneous signs. Diagnosis must be considered to avoid unnecessary debridement and extensive scars.

Background

For this case, we wanted to draw attention to a rare disease whose diagnosis remains difficult. A multidisciplinary approach including dermatologist, anatomopathologist, oncologist and surgeon is necessary to treat this condition and also to manage its possible malignant transformation. Sometimes this pathology can be fatal. Diagnosis must be known to avoid unnecessary excessive debridement and residuals scars.

Case presentation

A 64-years-old woman is admitted for an infection in the forehead area. The infection began 10 days ago and the patient mentions a possible spider bite. At first, she applied a cream containing urea on the lesion. Her medical history contains no dermatological diseases, but she has suffered from Crohn's disease with no event for 14 years and without treatment. Her medication is composed of an antidepressant (mirtazapine) and a proton pump inhibitor (rabeprazole).

At home, the initial treatment was composed of clindamycin (300 mg three times daily) and Fucicort cream (fusidic acid and betamethasone). The first clinical examination reveals an inflammatory wound with a diameter of 1 cm at the base of the scalp and frontal oedema extending to the eyes and nose.

Investigations

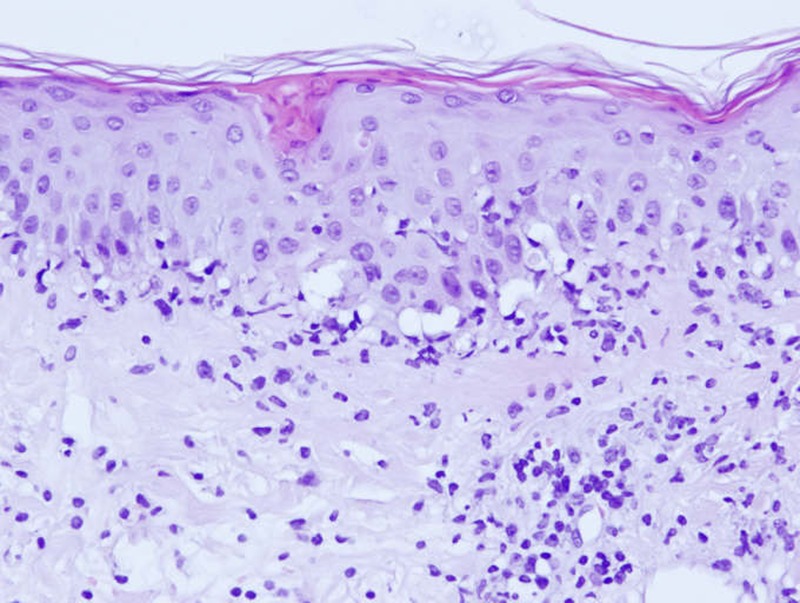

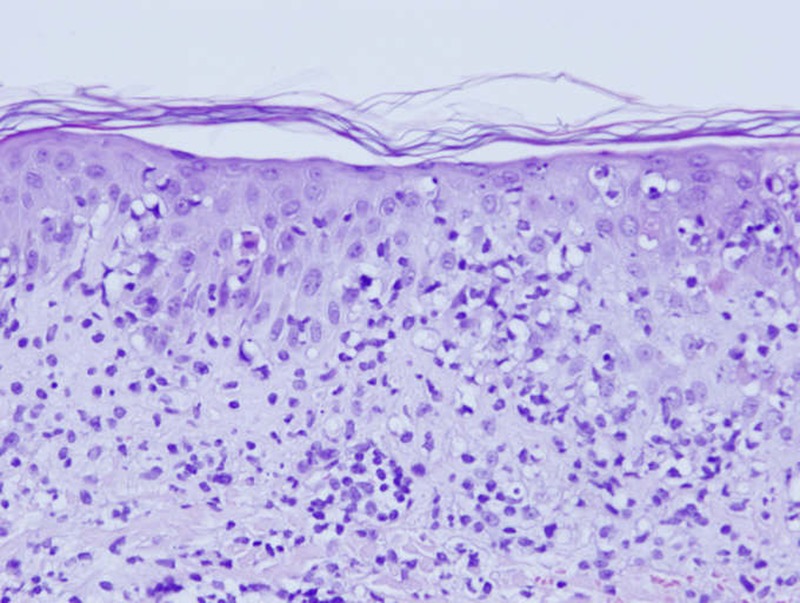

Her medical parameters were normal and laboratory tests revealed only a moderate inflammation (C reactive protein 15 mg/L normal value <5.0 mg/L). In front of the suspicion of erysipelas, antibiotic are continued intravenously. The evolution was marked on the day of admission by the rapid extension of the lesion and the appearance of necrosis (figure 1). Antibiotic therapy is extended with vancomycin, meropenem and combination of acyclovir as an antiviral. The computed tomodensitometry did not reveal any pathological picture. Microbiology of the wound has detected penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Despite combination therapy, necrosis (figure 2) extended and we noted the appearance of macula and papula away from the main lesion on the face and different parts of the body (back, abdomen and limbs). The palpation was painful but there was no sign of subcutaneous emphysema. The patient reported a headache, pruritus and a burning sensation. The general condition of the patient is preserved and its parameters are normal. She had no bowel disease symptoms. Given the lack of diagnosis and rapid progression of necrosis (figures 3 and 4), we performed a skin biopsy in different parts of the necrotic lesion and peripheral lesions. Histological examinations showed epidermal necrosis, the seat of many elements including inflammatory mononuclear cells, many neutrophils, eosinophils and a few red blood cells. The superficial dermis shows a lichenoid infiltrate invading the basal layer which shows apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes. There are also signs of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (figures 5 and 6). The histopathological report concludes with a pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). The immunohistology found intradermal and intraepidermal lymphocytes CD8 and some macrophages.

Figure 1.

One day after admission.

Figure 2.

Day 2.

Figure 3.

Day 3.

Figure 4.

Day 4.

Figure 5.

Seven months after treatment.

Figure 6.

H&E stain histological staining ×20: biopsy specimen showing acute findings consistent with Mucha-Habermann disease.

Differential diagnosis

At the first examination of the patient, our diagnosis of exclusion was a bacterial infection progressing to necrotising fasciitis. This condition is subject to a high rate of mortality.1–6 Diagnosis and early surgical treatment are essential to improve the prognosis and reduce sequelae.1 2 7–10 Among the risk factors, we found in our patient an advanced age and the presence of a wound. Although rare in the face,7 our case showed clinical signs of necrotising fasciitis but distinguished by the absence of fever, impaired general condition, subcutaneous emphysema (confirmed by the scanner). The diagnosis is not always easy and in case of doubt, the surgeon’s experience and histological examination play an important role.3 4

There is no standardisation of symptoms in febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) and necrotising fasciitis.

To assist in diagnosis, table 1 presents the main differences and similarities between FUMHD and necrotising fasciitis.

Table 1.

The main differences and similarities between FUMHD and necrotising fasciitis

| FUMHD | Necrotising fasciitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Local signs | ||

| Pain | Common and moderate | Common and intense |

| Oedema | Rare (present in our case) | Frequent |

| Bullae/blisters | Rare (present in our case) | Frequent |

| Skin colour | Violet | Violet |

| Hypoesthesia | Rare | Frequent |

| Necrosis | Frequent | Frequent |

| Ulceration | Frequent | Frequent |

| Crepitations | Rare | Frequent with Clostridium |

| Bleeding | Present | Absent |

| Rash (macula—papula) | Frequent | Rare |

| Lividity | Rare | Frequent |

| Burning | Frequent | Rare |

| Pruritus | Frequent | Rare |

| Satellite lesions | Frequent | Absent |

| General signs | ||

| Fever | Frequent | Frequent |

| Shock | Rare | Frequent |

| Blood analysis | ||

| Leukocytosis | Frequent | Frequent |

| C reactive protein | High | High |

FUMHD, febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease.

Treatment

Over the lack of response to treatment, on the day of the biopsy, systemic corticosteroids were started, intravenous methylprednisolone (120 mg) for 5 days relayed by oral form.

Outcome and follow-up

The follow-up was marked by rapid stabilisation of the lesions after 1 week and local improvement after 1 month. Her home medical treatment consisted of a regression therapy of methylprednisolone (Medrol) and ointment including hydrocortisone butyrate (Locoid Lipocream). Six months later, the patient presents only with a skin hypopigmentation area in the forehead (figure 7).

Figure 7.

H&E stain histological staining ×20: biopsy specimen showing acute findings consistent with Mucha-Habermann disease.

Discussion

Although Mucha-Habermann disease is a severe variant of PLEVA, it differs by rapid and painful evolution associated with systemic signs. In the acute form, this inflammatory dermatosis is characterised by the appearance of a rash initially composed of macula, papula topped by scales. These papula become vesicular-haemorrhagic pustules progressing to necrosis and ulceration. The ulceronecrotic form is characterised by rapid progression of necrotic papules that coalesce into large patches ulcerated. In general, lesions predominate on the trunk, roots and the ends of the limbs, but whole of the body can be affected including the mucous membranes. Systemic symptoms in the literature includes: high fever, neurological signs,5 asthenia, alteration of the clinical status, abdominal pain,5 6 diarrhoea,11 interstitial lung disease,12 cardiomyopathy,13 rheumatological manifestations,14 15 megaloblastic anaemia6 16 17 and death.18–22 The causes of death are due to: pneumonia,16 pulmonary thromboembolism,18 23 cardiac arrest,24 sepsis,20 22 23 25 hypovolemic shock21 and massive thrombosis of the superior mesenteric artery.23 The patient often reports of burning and pruritus. Healing occurs after several weeks or months,26–28 and there are varioliform scars and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation areas. Biological analyses are not specific and may show an increaseof leukocytes,15 29 30 the C reactive protein,15 19 22 liver enzymes,15 29 lactate dehydrogenase,19 sedimentation rate15 19 29 but also anaemia22 and hypoproteinaemia.17 In a recent article, 42 cases of FUMHD were found in the literature.31 The majority of cases occur in children and young adults with an average age 27.4 years.32 33 In FUMHD or PLEVA histological signs reveal at the dermoepidermal, parakeratosis areas often associated with scales containing nuclei of neutrophils. There is moderate acanthosis with necrotic keratinocytes over the entire height of the epidermis. The basal layer is vacuolated with a marked lymphocytic exocytosis. The superficial dermis is oedematous and the seat of a diffuse inflammatory infiltrate lichenoid type (neutrophils and eosinophils). These elements also infiltrate the skin appendages and vessels of the middle and deep dermis, with signs of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. There are extravasated red blood cells with intradermal haemorrhages.34 The diagnosis may be difficult when the lymphocytic infiltrate highlights atypical lymphocytes, posing a problem of differential diagnosis with mycosis fungoides or lymphomatoid papulosis.34 The immunohistochemical analysis allows identification of inflammatory cells. Most studies indicate that the proportion of CD8 T cell predominates in the PLEVA35–38 and CD4 T cells predominate in the pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC).38 39 Several authors have published cases of PLEVA where there was a clonal rearrangement of the T cell receptor with an increased risk to develop lymphoma.40 41 The receptor gene rearrangement invite to a prolonged monitoring of patients.

Although the pathogenesis of PLC remains unclear, several hypotheses have been proposed. One of the dominant explanations in the literature is a possible reaction to an infectious agent.5 6 15 42 In our case, the spider bite could be the trigger. The possible causes include: Toxoplasma gondii,43–47 Epstein-Barr virus,48–51 HIV,52–54 cytomegalovirus,15 varicella-zoster virus,55 parvovirus B19,56 57 Staphylococcus58 59 and the measles vaccine.60 Some drugs appear to be the cause of the disease. For example, chemotherapy agents (Tegafur),61 oestro-progestogenic contraceptives,62 antihistaminic drug,63 and some medicinal plants.64 Some authors believe that the PLC is a T cells lymphoproliferative disorder, while others believe that it's an immune complex disorder.65–68 Owing to the large number of possible aetiologies, many treatments have been used and their effectiveness varies from one patient to another. Among the treatments oral antibiotic use is the most common. Several authors have published cases of complete healing with the use of tetracycline,58 69 erythromycin or70 71 ciprofloxacin.59 It is important to note that the efficiency can range from complete remission to no improvement. Methotrexate is also effective in some patients with PLEVA72 or FUMHD.6 19 29 71 73 Finally, the efficient use of dapsone (antileprosy) has also been described.74–76 The use of phototherapy ultraviolet light A or B77–79 as well as psoralen+UVA treatment (PUVA) therapy80–83 have demonstrated their effectiveness, with a few cases of recurrence. Systemic corticosteroids are indicated in febrile ulcerative necrotic forms10 and associated with topical corticosteroids, they can decrease symptoms (pruritus and burning). In chronic forms, application of immunosuppressive ointment (tacrolimus) has proved its effectiveness. Effective treatment of ulcerative necrotic forms by oral administration of ciclosporin84–86 has been published. Treatment with inhibitor of tumour necrosis factor α has also been reported.32 Finally, some cases with important skin necrosis necessitate surgical debridement associated with a skin graft.

The choice of treatment depends on the severity of the pityriasis and the patient’s age. Most of the time a combination of several treatments is necessary to control the disease. In chronic forms, minimally symptomatic, treatment is not always necessary but sometimes antibiotics, phototherapy or topical corticosteroids are needed. On the other hand, for ulceronecrotic forms, antibiotics and corticosteroids must be started with or without PUVA (except children). In case of resistance to the first treatment, the use of dapsone, methotrexate or ciclosporin may be necessary. In children, the risk–benefit ratio must be taken into account. With this case, we wanted to draw attention to a rare disease whose diagnosis remains difficult. A skin biopsy is the best way to confirm the PLC and monitor, but there is no definite guideline for treatment. A multidisciplinary approach including dermatologist, anatomopathologist, oncologist and surgeon is necessary to treat this condition and its possible malignant transformation. Sometimes this pathology can be fatal. Diagnosis must be known to avoid unnecessary excessive debridement and subsequent scars.

Learning points.

All suspicious skin lesions of the FUMHD requires a biopsy.

Several treatments is necessary to control the disease.

Diagnosis must be known to avoid unnecessary excessive debridement.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Raffoul T, Fournier B, Lecomte C. Necrotizing fasciitis after a blunt trauma. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 2010;2013:78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kibadi K, Forli A, Martin Des Pallieres T, et al. [Necrotizing fasciitis: study of 17 cases presenting a low mortality rate]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 2013;2013:123–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamenkovic I, Lew PD. Early recognition of potentially fatal necrotizing fasciitis. The use of frozen-section biopsy. N Engl J Med 1984;2013:1689–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pruitt BA., Jr Biopsy diagnosis of surgical infections. N Engl J Med 1984;2013:1737–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Degos R, Duperrat B, Daniel F. Le parapsoriasis ulceronecrotique hyperthemique. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr 1966;2013:481–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warshauer BL, Maloney ME, Dimond RL. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease. Arch Dermatol 1983;2013:597–601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin C, Yeh FL, Lin JT, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck: an analysis of 47 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;2013:1684–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sepúlveda A, Sastre N. Necrotizing fasciitis of the face and neck. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;2013:814–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leong WC, Lipman J, Hon H, et al. Severe soft-tissue infections—a diagnostic challenge. The need for early recognition and aggressive therapy. S Afr Med J 1997;2013(Suppl 5):648–52, 654 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gindre S, Dellamonica J, Couadau E, et al. Face necrotizing fasciitis following spinocellular epithelioma excision. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 2005;2013:233–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang CC, Lee JY, Chen W. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with extensive skin necrosis in intertriginous areas. Eur J Dermatol 2003;2013:493–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auster BI, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease with interstitial pneumonitis. J Cutan Pathol 1979;2013:66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe NJ. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and suspected cardiomyopathy. J R Nav Med Serv 1975;2013:85–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luberti AA, Rabinowitz LG, Ververeli KO. Severe febrile Mucha-Habermann's disease in children: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol 1991;2013:51–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai KS, Hsieh HJ, Chow KC, et al. Detection of cytomegalovirus infection in a patient with febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease. Int J Dermatol 2001;2013:694–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Cuyper C, Hindryckx P, Deroo N. Febrile ulceronecrotic pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Dermatology 1994;2013(Suppl 2):50–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito N, Ohshima A, Hashizume H, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease managed with methylprednisolone semipulse and subsequent methotrexate therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;2013:1142–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoghton MAR, Ellis JP, Hayes MJ. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a fatality. J R Soc Med 1989;2013:500–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fink-Puches R, Soyer HP, Kerl H. Febrile ulceronecrotic pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;2013:261–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puddu P, Cianchini G, Colonna L, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease with fatal outcome. Int J Dermatol 1997;2013:691–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyamoto T, Takayama N, Kitada S, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol 2003;2013:795–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;2013:1014–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malnar T, Milavec-Puretic V, Rados J, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta with fatal outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;2013:303–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gungor E, Alli N, Artuz F, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease. Int J Dermatol 1996;2013:895–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aytekin S, Balci G, Duzgun OY. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and a review of the literature. Dermatol Online J 2005;2013:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longley J, Demar L, Feinstein RP, et al. Clinical and histologic features of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in children. Arch Dermatol 1987;2013:1335–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szymanski FJ. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: histopathological evidence that it is an entity distinct from parapsoriasis. AMA Arch Dermatol 1959;2013:7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hood AF, Mark EJ. Histopathologic diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and its clinical correlation. Arch Dermatol 1982;2013:478–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Estebaranz JL, Vanaclocha F, Gil R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;2013:902–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricci G, Patrizi A, Misciali D, et al. Pathological case of the month. Febrile Mucha-Habermann disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;2013:195–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrin BS, Yan AC, Treat JR. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease in a 34-month-old boy: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;2013:53–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsianakas A, Hoeger PH. Transition of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta to febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is associated with elevated serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Br J Dermatol 2005;2013:794–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sotiriou E, Patsatsi A, Tsorova C, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol 2008;2013:350–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavelier-Balloy B. Histopathologie cutanée—Pityriasis lichénoïde. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie 2006;2013:208–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood GS, Strickler JG, Abel EA, et al. Immunohistology of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Evidence for their interrelationship with lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;2013:559–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhlbauer JE, Bhan AK, Harrist TJ, et al. Immunopathology of pityriasis lichenoides acuta. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;2013:783–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varga FJ, Vonderheid EC, Olbricht SM, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction of lymphomatoid papulosis and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Am J Pathol 1990;2013:979–87 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannetti A, Girolomoni G, Pincelli C, et al. Immunopathologic studies in pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol Res 1988;2013(Suppl):S61–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers M. Pityriasis lichenoides and lymphomatoid papulosis. Semin Dermatol 1992;2013:73–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss LM, Wood GS, Ellisen LF, et al. Clonal T-cell populations in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (Mucha-Habermann disease). Am J Pathol 1987;2013:417–22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panhans A, Bodemer C, Macinthyre E, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides of childhood with atypicalCD30-positive cells and clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangements. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;2013:489–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuji T, Kasamatsu M, Yokota M. Mucha-Habermann disease and its febrile ulceronecrotic variant. Cutis 1996;2013:123–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinkerton H, Weinman D. In: Pinkerton H, Henderson RG. Adult toxoplasmosis. JAMA 1941;2013:807–14 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zlatkov NB, Andreev VC. Toxoplasmosis and pityriasis lichenoides. Br J Dermatol 1972;2013:114–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rongioletti F, Rivera G, Rebora A. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and acquired toxoplasmosis. Dermatologica 1987;2013:41–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nassef NE, Hammam MA. The relationship between toxoplasmosis and pityriasis lichenoides. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 1997;2013:93–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rongioletti F, Delmonte S, Rebora A. Pityriasis lichenoides and acquired toxoplasmosis. Int J Dermatol 1999;2013:372–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boss JM, Boxley JD, Summerly R, et al. The detection of Epstein Barr virus antibody in ‘exanthematic’ dermatoses with special reference to pityriasis lichenoides: a preliminary survey. Clin Exp Dermatol 1978;2013:51–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards BL, Bonagura VR, Valacer DJ, et al. Mucha-Habermann's disease and arthritis: possible association with reactivated Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Rheumatol 1989;2013:387–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almagro M, Del Pozo J, Martinez W, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like exanthema and primary infection by Epstein-Barr virus. Int J Dermatol 2000;2013:156–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klein PA, Jones EC, Nelson JL, et al. Infectious causes of pityriasis lichenoides: a case of fulminant infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;2013:S151–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ostlere LS, Langtry JAA, Branfoot AC, et al. HIV seropositivity in association with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Clin Exp Dermatol 1992;2013:36–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith KJ, Nelson A, Skelton H, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in HIV1 patients: a marker of early stage disease. Int J Dermatol 1997;2013:104–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griffiths JK. Successful long-term use of cyclosporine A in HIV induced pityriasis lichenoides chronica. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndrome Hum Retrovirol 1998;2013:396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boralevi F, Cotto E, Baysse L, et al. Is varicella-zoster virus involved in the etiopathogeny of pityriasis lichenoides? J Invest Dermatol 2003;2013:647–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sabarthe MP, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Ulcerations de la langue, parapsoriasis en gouttes et primo-infection A parvovirus B19. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1996;2013:735–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomasini D, Tomasini CF, Cerri A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated skin disorder. Evidence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in nine cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004;2013:531–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piamphongsant T. Tetracycline for the treatment of pityriasis lichenoides. Br J Dermatol 1974;2013:319–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.English JC, III, Collins M, Bryant-Bruce C. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and group A beta hemolytic streptococcal infection. Int J Dermatol 1995;2013:642–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Torinuki W. Mucha-Habermann disease in a child: possible association with measles vaccination. J Dermatol 1992;2013:253–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawamura K, Tsuji T, Kuwabara Y. Mucha-Habermann disease-like eruptions due to tegafur. J Dermatol 1999;2013:164–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hollander A, Grots IA. Mucha-Habermann disease following estrogen-progesterone therapy. Arch Dermatol 1973;2013:465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stosiek N, Peters KP, von den Driesch P. Pityriasis-lichenoides-et-varioliformis-acuta-like drug exanthema caused by astemizole. Hautarzt 1993;2013:235–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tanaka M. Drug-induced pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Rinsho Hifuka 1990;2013:307–10 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clayton R, Haffenden G, Du Vivier A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: an immune complex disease. Br J Dermatol 1977;2013:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clayton R, Haffenden G. An immunofluorescence study of pityriasis lichenoides. Br J Dermatol 1978;2013:491–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hayashi T. Pityriasis lichenoides varioliformis acuta: immunopathologic study. J Dermatol 1977;2013:477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hayashi T, Kawada A. Immunofluorescence study of pityriasis lichenoides chronica. J Dermatol 1980;2013:397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shelley WB, Griffith RF. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. A report of a case controlled by a high dosage of tetracycline. Arch Dermatol 1969;2013:596–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Truhan AP, Hebert AA, Esterly NB. Pityriasis lichenoides in children: therapeutic response to erythromycin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;2013:66–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romani J, Puig L, Fernandez-Figueras MT, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides in children: clinicopathologic review of 22 patients. Pediatr Dermatol 1998;2013:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lynch PJ, Saied NK. Methotrexate treatment of pityriasis lichenoides and lymphomatoid papulosis. Cutis 1979;2013:634–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suarez J, Lopez B, Villalba R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatology 1996;2013:277–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakamura S, Nishihara K, Nakayama K, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease and its successful therapy with DDS. J Dermatol 1986;2013:381–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kasamatsu M, Yokota M, Morita A, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease. Nishi Nihon Hifuka 1993;2013:665–9 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maekawa Y, Nakamura T, Nogami R. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann's disease. J Dermatol 1994;2013:46–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pasic A, Ceovic R, Lipozencic J, et al. Phototherapy in pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol 2003;2013:71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.LeVine MJ. Phototherapy of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol 1983;2013:378–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pinton PC, Capezzera R, Zane C, et al. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 therapy for pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;2013:410–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boelen RE, Faber WR, Lambers JCCA, et al. Long-term follow-up of photochemotherapy in pityriasis lichenoides. Acta Derm Venereol 1982;2013:442–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hofmann C, Weissmann I, Plewig G. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica: a new indication for PUVA therapy? Dermatologica 1979;2013:451–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brenner W, Gschnait F, Honigsmann H, et al. Erprobungvon PUVA bei verschiedenen Dermatosen. Hautarzt 1978;2013:541–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thivolet J, Ortonne JP, Gianadda B, et al. Photochimotherapie orale du parapsoriasis en gouttes. Dermatologica 1981;2013:12–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yanaba K, Ito M, Sasaki H, et al. A case of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease requiring debridement of necrotic skin and epidermal autograft. Br J Dermatol 2002;2013:1249–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Herron MD, Bohnsack JF, Vanderhooft SL. Septic, CD-30 positive febrile ulceronecrotic pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Pediatr Dermatol 2005;2013:360–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim HS, Yu DS, Kim JW. A case of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease treated with oral cyclosporine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;2013:247–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]