Abstract

Objectives

Visual impairment and blindness (VI&B) cause a considerable and increasing economic burden in all high-income countries due to population ageing. Thus, we conducted a review of the literature to better understand all relevant costs associated with VI&B and to develop a multiperspective overview.

Design

Systematic review: Two independent reviewers searched the relevant literature and assessed the studies for inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as quality.

Eligibility criteria for included studies

Interventional, non-interventional and cost of illness studies, conducted prior to May 2012, investigating direct and indirect costs as well as intangible effects related to visual impairment and blindness were included.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement approach to identify the relevant studies. A meta-analysis was not performed due to the variability of the reported cost categories and varying definition of visual impairment.

Results

A total of 22 studies were included. Hospitalisation and use of medical services around diagnosis and treatment at the onset of VI&B were the largest contributor to direct medical costs. The mean annual expenses per patient were found to be US$ purchasing power parities (PPP) 12 175–14 029 for moderate visual impairment, US$ PPP 13 154–16 321 for severe visual impairment and US$ PPP 14 882–24 180 for blindness, almost twofold the costs for non-blind patients. Informal care was the major contributor to other direct costs, with the time spent by caregivers increasing from 5.8 h/week (or US$ PPP 263) for persons with vision >20/32 up to 94.1 h/week (or US$ PPP 55 062) for persons with vision ≤20/250. VI&B caused considerable indirect costs due to productivity losses, premature mortality and dead-weight losses.

Conclusions

VI&B cause a considerable economic burden for affected persons, their caregivers and society at large, which increases with the degree of visual impairment. This review provides insight into the distribution of costs and the economic impact of VI&B.

Keywords: Visual Impairment, Blindness, Cost of Illness, Health Economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first international and multiperspective overview of costs and intangible effects associated with visual impairment and blindness.

The review is able to demonstrate a considerable impact of visual impairment and blindness.

The study synthesis of the reviewed literature was limited as no two studies used the same methodology, reported exactly the same outcomes or used the same sample population. Therefore a meta-analysis could not be conducted.

Introduction

Visual impairment and blindness are foremost a problem of older age in all high-income countries and constantly increasing due to the ageing of populations.1 Globally, the burden of disease related to vision disorders has increased by 47% from 12 858 000 disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in 1990 to 18 837 000 DALYs in 2010.2 In high-income countries, health-related quality of life in severely visually impaired persons has been shown to be similar or even lower and emotional distress higher compared with other serious chronic health conditions such as stroke or metastasised solid tumours.3 Blindness and visual impairment impact not only the individual but also the family, caregivers and the community, leading to a significant cost burden. In Australia, the overall cost placed visual disorders seventh among diseases, ahead of coronary heart disease, diabetes, depression and stroke in terms of economic burden on the health system.4

As demands on healthcare continue to increase in all high-income countries, economic evaluations of disease, impairment and interventions have also become increasingly important.5 This necessitates a clear understanding of all aspects of the direct and indirect costs and intangible effects related to blindness and severe visual impairment, as almost all interventions in this area are aiming to prevent these and are often measured as an incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER), that is, the difference in cost compared to the difference in effectiveness. Similarly, faced with the increasing demand and limited resources in healthcare, these resources need to be prioritised, which again calls for a clear understanding of the economic impact of a disease or disorder. Against this background, we conducted a systematic review of the literature, collating all data available on the economic impact of VI&B.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted as suggested in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement which aims to improve the quality of systematic reviews by providing guidance and a 27-item checklist to aid in structuring methods and improving the reporting of results. It focuses on randomised trials, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research, for example, health economic evaluation studies. However, the checklist should not be used as a quality assessment instrument to measure the quality of included studies or the performed systematic review.6 The completed PRISMA checklist for this review can be found in online supplementary appendix 3.

Literature search

All economical and medical databases were searched from May to June 2012 through PubMed and OVID using the following terms

“low vision”, “visual impairment”, “visually impaired”, “blindness”, “blind”, “visual loss”, “costs”, “costs of illness”.

Subsequently, a second search was conducted using the main causes of visual impairment and blindness. Search terms were: ‘low vision’, ‘visual impairment’, ‘visually impaired’, ‘blindness’, ‘blind’, ‘visual loss’, ‘costs’ combined with ‘age-related macular degeneration’, ‘glaucoma’, ‘diabetic retinopathy’, ‘cataract’, ‘corneal opacities’, ‘childhood blindness’ separated by ‘or’.

Supplemental sources including references contained in identified articles were used in addition.

Two independent researchers screened identified articles using the following inclusion or exclusion criteria:

Inclusion

Data for direct and indirect costs related to VI&B. Cost-of-illness—or in this case cost-of-impairment—studies can be divided into disease-specific and general studies. Both types of studies were included if they contained relevant data.

Studies with outcomes related to intangible effects due to visual impairment and blindness.

Overall data for burden of illness related to affected persons and carers.

Exclusion

Costs pertaining to underlying diseases only with no specification of visual impairment levels.

Economic studies conducted in developing countries.

As we were interested in the burden of VI&B in high-income countries only, we excluded economic studies conducted in developing countries. Health services provision and treatment options differ vastly between high-income and middle-income or low-income countries, making a comparison of cost categories unfeasible.

Cost classification

All included articles were assessed as to which cost aspects they reported. Broadly, costs were divided into direct costs, indirect costs and intangible effects.7

Direct costs are defined as the actual expenses related to an illness and contain medical costs, non-medical costs and other direct costs.5 Medical costs measure the cost of resources used for treating a particular illness. Non-medical costs are costs caused by the disease but not attributed to medical treatment. In case of VI&B, these are supporting services, assistive devices, home care, residential care or transportation (travel expenses). Other direct costs comprise informal care, time spent in treatment by patients or caregivers or time spent in rehabilitation, training, self-help groups or preventative activities.5

Indirect costs are defined as the value of lost output caused by reduced productivity due to illness or disability.8Patients and caregivers are affected by indirect costs due to allowances (financial support for income, residence, benefits), productivity losses (absenteeism, salary losses, part-time employment, loss of work) and dead-weight losses as well as years of life lost. Dead-weight loss, also known as an excess burden, is not a clearly defined concept. In a purely economic sense, dead-weight loss describes the costs to society created by market inefficiency. In the context of our study, we refer to it as an excess financial burden on society caused by VI&B.

Intangible costs or effects refer to the burden of illness of affected persons and caregivers, and comprise, among others, loss of well-being or loss of quality of life. It can be captured using questionnaires and expressed in DALYs. As this aspect of costs is difficult to quantify, DALYs or other measures of intangible effects are rarely assigned a monetary value.

Commonly, cost categories considered in a particular study depend on the perspective the study is conducted from, that is, a healthcare payer's (direct medical and non-medical costs only) or patient's perspective, or a societal perspective (all costs).

As cost categories varied considerably between all cost-of-illness studies, all different direct and indirect cost categories were listed in online supplementary appendix 2 prior to being categorised into our broader categories as outlined above.

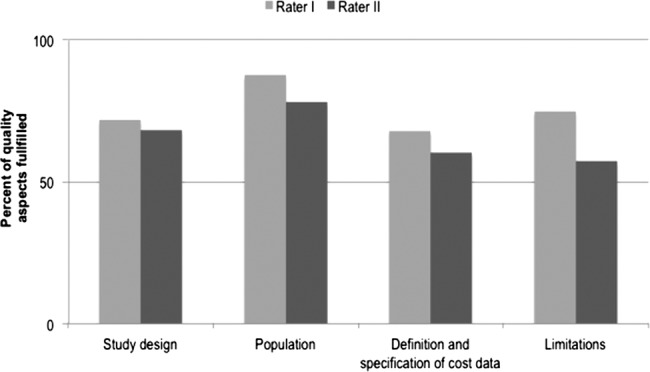

Quality of included studies

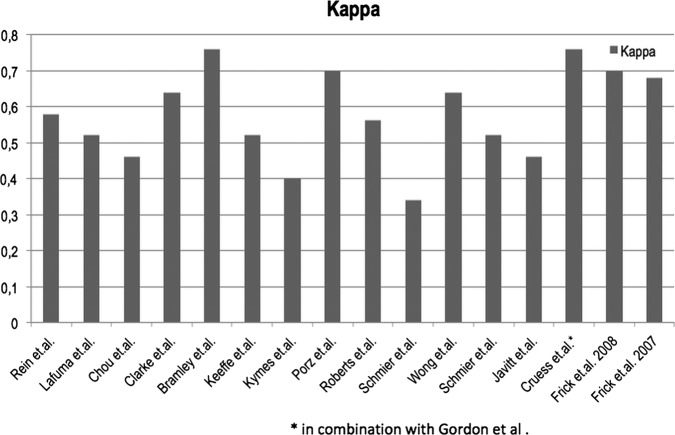

A checklist, based on the assessment tool of Emmert et al9 and extended by several questions covering relevant cost-of-illness aspects (see online supplementary appendix 1), was generated to assess the overall quality of included studies reporting direct or indirect costs of illness. The checklist contained sections on the study design, population, definition and specification of cost data and their limitations, including a total of 25 questions. Studies were rated from 0 to 100 for each of these categories. Two independent reviewers conducted the assessment and the interrater-reliability was assessed using κ (κn) as suggested by Brennan and Prediger10 for every study. The interpretation of the agreement was based on the agreement scale by Landis and Koch,11 which indicates fair agreement at κ levels between 0.21 and 0.40, moderate agreement between 0.41 and 0.60, substantial agreement between 0.61 and 0.80 and almost perfect agreement between 0.81 and above.

Conversion of cost-of-illness study results

For better comparison of costs across studies, the data were transformed: (1) costs were inflated to 2011 using a country-specific gross domestic product deflator, which takes fluctuating exchange rates, different purchasing power of currencies and the rate of inflation into account12 13 and (2) converted to USD using purchasing power parities (PPP).14 PPPs account for differences in price levels between countries, and convert local currencies into international dollars by taking the purchasing power of different national currencies into account and eliminating differences in price levels between countries. The transformed values are presented in million units (million US$ PPP) for total expenditures reported and in US$ PPP for costs per person.

Results

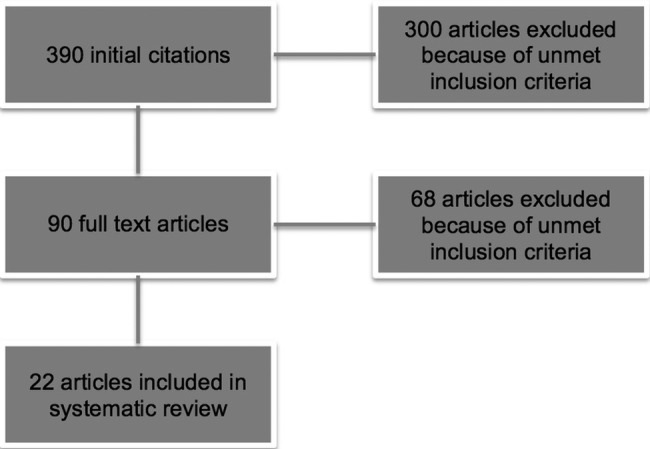

The search yielded a total of 390 articles. After applying all inclusion and exclusion criteria, 22 studies were included in the systematic review (figure 1). Altogether, there were nine studies conducted in the USA, six studies conducted in Australia, two studies from France and Canada and one study from each of the following countries: Germany, the UK, Japan. All included studies are summarised in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature search.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Country | Design and population | Cost components evaluated | Objective | Vision categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bramley et al15 | USA | Retrospective cohort analysis of a nationally representative Medicare 5% random sample; patients older than 65 years with newly diagnosed glaucoma; regression analysis | Direct medical costs, intangible effects | To measure costs of visual impairment due to progressing glaucoma | No vision loss, moderate vision loss, severe vision loss, blindness |

| Brezin et al16 | France | National survey of a random stratified sample; 16 945 affected persons answered questionnaires; 4091 caregiver answered questionnaires | Indirect costs, intangible effects | To document the prevalence of self-reported visual impairment and its association with disabilities, handicaps and socioeconomic consequences | Blind or light perception only, low vision, other visual problems and no visual problems |

| Chou et al17 | Australia | 150 persons completed cost diaries for 12 months and were evaluated; costs categorised into four sections: (1) medicines, products and equipment, (2) health and community services, (3) informal care and support, (4) other expenses | Direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs | To describe and evaluate the process used to collect personal costs (out-of pocket) associated with vision impairment using diaries | ≥ 6/12 with restricted fields; <612–6/18; <6/18–6/60; <6/60–3/60; <3/60 |

| Clarke et al18 | UK | Regression-based approach to estimate the short-term and long-term annual hospital and non-hospital costs associated with seven major diabetes-related complications in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study: myocardial infarction; stroke, angina or ischaemic heart disease; heart failure; blindness in one eye; amputation and cataract extraction; 5102 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes | Direct medical costs | To estimate the immediate and long-term health-care costs associated with seven diabetes-related complications | Blind in one eye |

| Cruess et al19 (in combination with Gordon et al20) | Canada | Prevalence-based approach; population projections for the whole population were compiled using data from the Statistics Canada 2006 Population Projections for Canada, Provinces and Territories 2001-2031 | Direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, indirect costs, intangible effects | To investigate costs of vision loss in Canada to inform healthcare planning | No details |

| Frick et al21 | USA | Retrospective cohort study; patients with blindness matched to non-blind selected from managed care claims database | Direct medical costs | To evaluate total and condition-related charges incurred by blind patients in a managed care population in the USA | Blind, non blind |

| Frick et al22 | USA | Data from the medical expenditure panel survey 1996—2002 for adults older than 40 years with visual impairment or blindness | Direct medical costs; direct non-medical costs; other direct costs; intangible effects | To estimate the economic impact of visual impairment and blindness in persons aged 40 years and older in the USA | Visual impairment; blindness |

| Javitt et al23 | USA | Retrospective cohort analysis of a nationally representative Medicare 5% random sample, excluding Medicare managed-care enrollees | Direct medical costs | To assess and identify the costs to the Medicare programme for patients with either a stable or progressive vision loss and estimate the impact on eye-related and non-eye-related care | Mild, moderate, severe vision loss (VA ≤20/200), blindness (VA ≤ 20/400) |

| Keeffe et al24 | Australia | 114 participants of the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project completed diaries for 12 months; the burden of caregiver and opportunity costs for losses in work time was calculated (in combination with methods and data from Chou et al) | Other direct costs | To analyse prospective data on providers, types and costs of care for people with impaired vision in Australia | VA <20/40 |

| Kymes et al25 | USA | Decision analytic approach; Markov model to replicate health events over the remaining lifetime of someone newly diagnosed with glaucoma | Incremental costs of illness | To evaluate the incremental cost of primary open-angle glaucoma considering the visual and non-visual medical costs over a lifetime | No details |

| Lafuma et al26 | France | Interviews with a sample population (665 000) from a national survey of persons living in institutions or in the community (with a caregiver at home) | Direct non-medical costs, other direct costs, indirect costs | To estimate the annual national non-medical costs due to visual impairment and blindness | Blind (light perception), low vision (better than light perception?, low vision and controls |

| McCarty et al27 | Australia | Population-based study; evaluation of the data from the Melbourne Visual impairment project; population ≥40 years was analysed in causes of death | Intangible effects | To describe predictors of mortality in the 5-year follow-up of the Melbourne Visual impairment project | Visual acuity <6/12 |

| Morse et al28 | USA | 2 552 350 discharges from hospital in the state of NY >5.764 patients had visual impairment | Direct medical costs | To assess whether visual impairment contributes to the average length of stay within inpatient care facilities | No details |

| Porz et al29 | Germany | Retrospective study of 66 patients using a cost-related and a vision-related quality of life questionnaire (impact of vision impairment questionnaire) | Direct non-medical costs, intangible effects | To capture the costs of medicines, aids and equipment, support in everyday life and social benefits, as well as vision-related quality of life | Visual acuity ≥0.3, Visual acuity <0.3 |

| Rein, et al30 | USA | Private insurance and Medicare claims data | Direct non-medical costs, indirect costs | To estimate the societal economic burden and the governmental budgetary impact of the following visual disorders among US adults aged 40 years and older: visual impairment, blindness, refractive error, age-related macular degeneration, cataracts, diabetic retinopathy and primary open angle glaucoma | Refractive errors |

| Roberts et al31 | Japan | Prevalence-based approach; adopted using data on visual impairment, the national health system and indirect costs | Direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, indirect costs and intangible effects | To quantify the total economic cost of visual impairment in Japan | Low vision 6/12–6/60; blind <6/60; visual impairment>6/12 |

| Schmier et al32 | USA | Using a questionnaire that included items on demographic and clinical characteristics and on the use of services, assistive devices and caregiving; 761 persons were included | Direct non-medical costs, other direct costs | To assess the use of devices and caregiving among individuals with diabetic retinopathy and to evaluate the impact of visual acuity on use | Group 1 (20/20 or better), group 2 (20/ 25–20/30), group 3 (20/40–20/50), group 4 (20/60–20/70), or group 5 (20/80 or worse) |

| Schmier et al33 | USA | Survey with interviews on Daily Living Tasks Dependent on Vision Questionnaire; 803 respondents | Other direct costs | To assess the patient-reported use of caregiving among individuals with age-related macular degeneration and evaluation of impact of visual impairment level on this use | 1. VA >20/32; 2. VA 20/32—> 20/50; 3. VA 20/50—>20/80; 4. VA 20/80—> 20/150; 5. 20/150—>20/250; 6. VA ≤ 20/250 |

| Vu, et al34 | Australia | Stratified random sample of 3040 participants from the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project; 2530 attended the follow-up study | Intangible effects | To investigate whether unilateral vision loss reduces any aspects of quality of life in comparison with normal vision | Unilateral and bilateral vision loss (correctable and non-correctable) |

| Wong et al35 | Australia | Prospective cohort study; participants of any age to complete a diary for 12 months answering four categories: (1) medicines, products and equipment, (2) health and community services, (3) informal care and support and (4) other expenses | Direct costs (medical and non-medical), other direct costs | To determine the personal out-of-pocket costs of visual impairment and to examine the expenditure pattern related to eye diseases and the severity of visual impairment | Visual acuity ≥6/18 with constricted. fields; <6/18–6/60; <6/60 |

| Wood et al36 | Australia | 76 community-dwelling individuals with a range of severity of AMD; completing a diary for 12 months | Intangible effects; costs of adverse events | To explore the relationship between AMD, fall risk, and other injuries and identified visual risk factors for these adverse events | Binocular visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and merged visual fields |

AMD,age-related macular degeneration; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; UKPDS, UK Prospective Diabetes Study; VA, visual acuity.

All 17 of 22 studies dealing with direct or indirect costs of illness were rated above 50 for all four main quality aspects, indicating a sufficient level of quality, and consequently were included in the review (see figure 2). The interrater-reliability was consistently high and only a few discrepancies had to be settled by a discussion between the two raters. κ scores ranged from 0.34 to 0.76 (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Quality rating of included studies.

Figure 3.

κ-Index per study.

Of all the included studies, 12 captured direct medical costs, 10 direct non-medical costs and six other direct costs. Six studies reported data on indirect costs and 10 studies on intangible effects. All cost components reported by studies within each cost category are summarised in online supplementary appendix 2, highlighting the considerable variability in obtaining and reporting cost aspects related to VI&B between all studies.

Direct medical costs

Direct medical costs occurred mostly due to hospitalisation, the use of medical services and medical products, and were reported either as incremental costs or, in some studies, provided as the length of hospital stay (table 2).

Table 2.

Results for direct medical costs

| Study | Cost outcomes | US$ PPP in 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Bramley et al15 | Annual costs per patient compared in degrees of vision impairment from no vision loss to onset of moderate or severe vision impairment or blindness | |

| No vision loss US$8157 | 8695 | |

| Moderate visual impairment US$13 162 | 14 029 | |

| Severe visual impairment US$15 312 | 16 321 | |

| Blindness US$18 670 | 19 900 | |

| Frick et al22 | Total expenditures on healthcare in blind and visually impaired persons ≥40 years | |

| Blindness individual excess medical expenditures US$2157 | 2621 | |

| Total excess medical expenditures US$2454 million | 2982 million | |

| Visual impairment individual excess medical expenditures US$1037 | 1260 | |

| Total excess medical expenditure US$2661 million | 3233 million | |

| Total annual monetary impact for VI and blindness (primarily owing to home care) US$5100 million | 6197 million | |

| Frick et al21 | Cohort with legally blind patients matched to an equal sample cohort with non-blind patients (annual costs per patient in the first year) | |

| Blind persons mean costs US$20 677 | 24 180 | |

| Median costs US$6854 | 8015 | |

| Non-blind mean costs US$13 321 | 15 578 | |

| Median costs US$371 | 434 | |

| Javitt et al23 | Patients with normal vision compared to moderate or severe visual impairment or blindness regarding eye-related and non-eye-related care | |

| Mean annual costs for eye-related care | ||

| Normal vision US$370 | 445 | |

| Moderate visual impairment US$345 | 415 | |

| Severe visual impairment US$407 | 490 | |

| Blindness US$237 | 285 | |

| Mean annual values for non-eye related costs | ||

| Normal vision US$7928 | 9537 | |

| Moderate visual impairment US$2193 | 2638 | |

| Severe visual impairment US$3301 | 3971 | |

| Blindness US$4443 | 5345 | |

| Kymes et al25 | Lifetime costs of POAG (primary open-angle glaucoma) to non-POAG patients | |

| Incidence costs US$41 039 | 46 456 | |

| Prevalence costs US$19 268 | 21 811 | |

| Drug costs US$7098 | 8035 | |

| Incremental incidence costs US$27 326 | 30 933 | |

| Incremental prevalence costs US$5555 | 6288 | |

| Incremental drug costs US$4179 | 4731 | |

| Morse et al28 | Extension of average length of stay in hospitals due to visual impairment | |

| 5.2 days longer stay | ||

| Cruess et al19 | Financial burden of vision loss to Canadian healthcare system | |

| Hospital $C1497.7 million | 1934.72 million | |

| Physicians $C866.5 million | 1119.34 million | |

| Vision care $C3483.7 million | 4500.24 million | |

| Chou et al17 | The out-of-pocket expenses for medicines and products per person annually | |

| $A206 | 456 | |

| Wong et al35 | Annual costs for medicine and products per patient | |

| Visual acuity (VA) ≥6/18 with restr. field $A285 | 632 | |

| <6/18—6/60=$A233 | 516 | |

| < 6/60=$A147 | 326 | |

| Clarke et al18 | Short-term and long-term annual hospital and non-hospital costs due to major diabetes-related complications | |

| Blindness in one eye (in 20% of patients) £ 4370 | 4086 | |

| Mean hospital in-patient costs £872 | 815 | |

| Roberts et al31 | Total economic costs of visual impairment | |

| General medical expenditure US$8.102 billion | 8636 million | |

| In-patient US$1808 billion | 1927 million | |

| Outpatient US$6.294 billion | 6709 million | |

| Drugs US$1.395 billion | 1487 million |

POAG,primary open-angle glaucoma; VA,visual acuity.

At the onset of VI&B, the two major contributors to direct medical costs are hospitalisations and costs due to the increased use of medical services around diagnosis and treatment.18 19 21 22 28 31 Costs related to the recurrent hospitalisations and ongoing but less frequent use of medical services remain major cost components in persons with VI&B in the long term. Costs related to drugs, however, did not emerge as a major direct cost factor.17 35 All identified costs correlated with the degree of visual impairment leading to the highest expenditures being associated with blindness. The considerable differences in study methods and reported outcomes makes a head-to-head comparison of results by study or country or aggregation of data in terms of meta-analyses for direct medical costs very difficult. Several studies based on representative samples of Medicare beneficiaries in the USA reported mean annual expenses per patient to be US$ PPP 12 175–14 029 for moderate visual impairment, US$ PPP 13 154–16 321 for severe visual impairment and US$ PPP 14 882–24 180 for blindness, which is almost a 100% excess of the estimated mean annual cost for non-blind patients at the upper end of the range (table 2).

Direct non-medical costs

Assistive devices and aids, home modifications, costs for healthcare services such as home-based nursing or nursing home placements were the major contributors to direct non-medical costs (table 3). With worsening visual acuity, direct non-medical costs for support services and assistive devices increased from US$ PPP 53.90 for a person with visual acuity ≥20/20 up to US$ PPP 608.71 for a person with visual acuity ≤20/80.32 Nursing home-placements and professional care costs incurred the highest expenditures followed by domestic modifications. These costs, however, were highest initially shortly after the loss of vision and in the majority were incurred only once (table 3).

Table 3.

Results for direct non-medical costs

| Study | Cost outcomes | US$ PPP in 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Frick et al22 | Total healthcare expenditures for adults ≥40 years (excess costs) | |

| Blindness home health agencies US$4988 | 6060 | |

| Low vision home health agencies US$3105 | 3773 | |

| Expenditures for private home health providers was US$1200 more for the blind than the visually impaired persons | ||

| Rein et al30 | Total annual costs for visual impairment and blindness for adults ≥40 years | |

| Nursing placements of US$10.96 billion | 12 818 million | |

| Guide dogs US$0.062 billion | 72.5 million | |

| Independent living US$0.029 billion | 33.9 million | |

| Schmier et al32 | Annual costs for use of services and devices related to the degree of visual impairment per person | |

| Devices (glasses, sticks, computer software etc. US$109.79 | 120 | |

| Rehabilitation US$7.09 | 7.78 | |

| Chou et al17 | Annual costs for health and community services per person | |

| Healthcare, home help, personal affairs, personal care, communication, transport, social activities $A 872 | 1932.50 | |

| Expenditure for taxi, public transport, education expenses, guide dog $A 321 | 711 | |

| Cruess et al19 | Financial burden of vision loss to the Canadian healthcare system | |

| Care costs $C693 million | 895 21 million | |

| Aids and modification $C305 million | 394 million | |

| Wong et al35 | Annual personal costs for health and community services and other expenses per patient | |

| Median total costs $A1768 | 3919 | |

| Mean total costs $A3376 | 7482 | |

| Roberts et al31 | Total economic costs of visual impairment | |

| Meal service on admission US$0.149 billion | 158.81 million | |

| Home-visit nursing US$0.013 billions | 13.86 million | |

| Healthcare administration US$0.475 billion | 506.30 million | |

| Community care US$6.608 billion | 7043 million | |

| Institutional care US$0.238 billion | 253 68 million | |

| Vision aids US$0.2 billion | 213 18 million | |

| Porz et al29 | Financial and psychological burden of retinal diseases divided into health economic relevant categories; annual expenses per person | |

| Aids for VA ≥0.3=€96.65 | 77.39 | |

| VA <0.3=€83.58 | 66.92 | |

| Personal assistance VA ≥0.3=€454.96 | 364 28 | |

| VA <0.3=€667.77 | 534 68 | |

| Lafuma et al26 | National survey with estimation on costs of low vision and blindness for persons living in institutions or in the community (declared annually per person and total expenditures) | |

| Low vision; blindness | Low-vision; blindness | |

| Home modifications* €36.65 pp/year; €926.96 pp/year | 37.87; 957.90 | |

| €3.27 million total; €9.63 million total | 3.375 million 9.95 million | |

| devices* €184.14 pp/year; €387.35 pp/year | 190.29; 400.28 | |

| €16.43 million total; €4.03 million total | 16.98 million 4.165 million | |

| home modification† €42.23 pp/year; €121.12 pp/year | 43.64; 125.16 | |

| €16.43 million total; €7.02 million total | 16.98 million 7.25 million | |

| devices† €376.39; €363.14 pp/year | 388.95; 375.26 | |

| 420 million total; €21.04 million total | 434.02 million 21.74 million | |

| paid assistance† €1463.59 pp/year; €6750.66 pp/year | 1512.446 976 | |

| €1635 million; €391 million total | 1690 million 404 million |

Other direct costs

Six of the included studies reported costs caused by informal care. Time spent on caring for or assisting visually impaired persons was related to the degree of visual impairment, with blind persons requiring the most assistance. The time spent by caregivers ranged from 5.8 h/week for a person with a visual acuity of >20/32 and a cost of US$ PPP 263 up to 94.1 h/week and costs of US$ PPP 55 062 for persons with a visual acuity of ≤20/250.33 All studies differed slightly as to the nature of direct costs assessed. Some studies reported on governmental, out-of-pocket expenses as well as opportunity costs, whereas others considered only one or two of these. The wide range of time and resources spent on informal care provision demonstrates the broad economic impact and considerable burden of informal care provision with concurrent expenses at a personal and societal level. Again, the reported cost aspects and methodologies differ considerably with, for example, Keeffe et al24 reporting out-of-pocket expenses and Lafuma et al26 reporting time spent on caring using an hourly rate. The multitude of differing approaches in each study does not allow for a head-to-head comparison but gives a comprehensive impression of the complex cost situation and highlights the importance of providing assistance to VI&B (table 4).

Table 4.

Results for other direct costs

| Study | Cost outcomes | US$ PPP in 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Frick et al22 | The economic impact of blindness and visual impairment on adults ≥40 years | |

| Blindness causes mean individual excess informal care days 5.2 | ||

| Visual impairment causes mean individual excess informal care days 1.2 | ||

| Blindness causes total excess informal care costs US$242 million | 294.03 million | |

| Visual impairment total excess informal care costs US$124 million | 150.66 million | |

| Schmier et al32 | Annual costs for caregiver time spent in supporting patients with macular degeneration | |

| US$5038 | 5526 | |

| Schmier et al33 | Annual costs for quantity of caregiver time addicted to the degree of visual impairment per patient diabetic retinopathy | |

| Mean 5.7 h a day 5 days a week | ||

| oOverall amount of US$9572.77 | 11 194.40 | |

| Keeffe et al24 | Personal out-of-pocket expenses regarding the burden of caregiver | |

| Median annual opportunity costs for work time spent on caregiving $A915 | 2244.60 | |

| Wong et al35 | Annual median personal costs for informal care and assistance in activities of daily living | |

| For example, meal preparing, dressing, shopping, transportation $A2911 | 6451 | |

| Lafuma et al26 | National survey with estimation on costs for time caregiver spent on low vision and blindness for persons in the community (declared annually per person and total expenditures) | |

| Low-vision; blindness | low-vision; blindness | |

| Informal care €1881.81 pp/year; €7316.26 pp/year | 1944; 7560.48 | |

| €2101 million total; €424 million total | 2171 million; 438 million |

Indirect costs

Studies of indirect costs demonstrate high expenditures related to productivity losses, changes in employment (employer and/or area of work), loss of income, premature mortality and dead-weight losses (table 5). Received social allowances were detailed in one study but not counted towards the overall costs as they were considered as transfer costs.29 One study included the loss of caregivers’ time, which is spent not only on support in terms of productivity loss but also as a loss of personal time and time to engage in leisure activities.26 Equal to other cost components, indirect costs correlated with the degree of visual impairment, with the highest indirect costs reported for blind persons. Compared to all other cost categories, indirect costs due to productivity losses, lower employment rates and losses of income in patients as well as caregivers caused the highest economic burden. Annual estimates of productivity losses and absenteeism due to VI&B in the USA and Canada range from US$ PPP 4974 to 5724 million, and are estimated to be US$ PPP 7367 million for an overall decrease in workforce participation in the USA (table 5).

Table 5.

Results for indirect costs

| Study | Cost outcomes | US$ PPP in 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Rein et al30 | Total annual indirect costs caused by visual disorders | |

| Decreased work force participation US$6.3 billion | 7367 million | |

| Decreased wages US$1.73 billion | 2023 million | |

| Roberts et al31 | Indirect costs for visual impairment and blindness | |

| Productivity losses US$4.667 billion | 4974 million | |

| Lower employment US$4.230 billion | 4509 million | |

| Absenteeism US$0.384 billion | 409 million | |

| Premature mortality US$0.053 billion | 56.5 million | |

| Dead-weight losses US$1.609 billion | 1715 million | |

| Lafuma et al26 | National survey with estimation on indirect costs for losses of income in persons with low vision and blindness living in institutions or in the community (declared annually per person and total expenditures) | |

| low-vision; blindness | low-vision; blindness | |

| losses of incomes €120.00 pp/year; €180.00 pp/year | 124; 186 | |

| €10.71 million total; €1.87 million total | 11.07 million 1.93 million | |

| losses of incomes† €3912.00 pp/year; €3168.00 pp/year | 4042; 3273 | |

| €4369 million total; €183.6 million total | 4515 million 189.72 million | |

| Brezin et al16 | Prevalence and burden of blindness, low vision and visual impairment in the French community (estimation of monthly average value) | |

| low-vision; blindness | low-vision; blindness | |

| Social allowances €87; €364 | 92; 384 | |

| Total household income €1525; €1587 | 1607; 1673 | |

| Household income no VI €1851 | 1951 | |

| Cruess et al19 | Indirect costs for Canada caused by vision loss | |

| Employment participation, absenteeism, presenteeism CAN$4431 million | 5724 million | |

| Dead-weight losses $C1757 million | 2270 million |

Intangible effects

Most studies used personal burden such as depression, emotional distress, loss of independency, loss of quality of life, limitations in activities of daily living or hazards such as falls and injuries to capture intangible effects of VI&B. Two studies, set in Japan and Canada, reported a loss of well-being as DALYs and an associated cost of US$ PPP 51.8 billion and US$ PPP 15.11 billion/year, respectively.19 31 Every reviewed study reported a high burden caused by multiple individual restrictions in patients and also in caregivers, which was found to be increasing with the degree of visual impairment (table 6). Mortality associated with visual impairment was reported to increase linearly from 4.5% in persons with normal visual acuity (≥20/20) to 22.2% in blind persons (visual acuity of <20/200).27 Measured as a restriction in caregivers, Brezin et al16 reported an increase from 1.6% of caregivers of non-visually impaired persons, who reported restrictions in going out during the day, up to 12% for caregivers of blind patients.

Table 6.

Results for intangible effects

| Study | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Bramley et al15 | Depression occurs in patients with vision loss more often (about 17%) than in patients with no vision loss, placements in nursing homes are demanded in 25.3% more, injuries happen in 33.4% more cases and femur fractures in 67.4% more cases |

| Cruess et al19 | Loss of well-being and loss in quality of life evokes 77 306 DALYs or rather $C 11.7 billion in 2007 (US$ PPP 15.11 billion in 2011) |

| Vu et al34 | Non-correctable unilateral vision loss was addicted to independent living and reduced safety; bilateral non-correctable vision loss was associated with nursing homes, emotional well-being, use of community services, and activities of daily living |

| Wood et al36 | Increased visual impairment was significantly associated with an increased incidence of falls and other injuries. 54% of participants had at least one fall, 30% had more than one fall and 63% of falls ended in injuries |

| McCarty et al27 | A linear increase of 5-year mortality correlating with a degree of visual impairment was detected; even mild visual impairment is related to a more than twofold risk of death |

| Brezin et al16 | A burden in patients occurs because of the inability to undertake daily activities; the need for assistance correlates with the degree of visual impairment; the burden on the caregiver was caused by the restricted possibilities for going out for different periods or losing social contacts, affected physical and mental welfare and modified professional activities |

| Porz et al29 | In a questionnaire with a score scale 0–100 points, patients with VA ≥0.3 achieved 79.32 for mobility and independency, 69.64 for emotional well-being and 73.86 for reading and achievement of information; persons with VA <0.3 were rated with scores of 46.84, 61.43 and 44.25, respectively |

| Roberts et al31 | Loss of well-being was measured in DALYs; converted into a monetary value, this results in total annual costs of US$ 48.598 billion (US$ PPP 51.8 billion in 2011) and costs per capita of US$ 29 690 per year (US$ PPP 31 647) |

| Frick et al22 | The cases of blindness and visual impairment more than 209 000 QALY were projected to lost each year, this amounts to a monetary value of US$ 10 000 million (US$ PPP 12 150 in 2011) |

DALYs,disability adjusted life years; VA,visual acuity.

Discussion

In this first systematic review of costs associated with VI&B, we could demonstrate a considerable impact of VI&B in terms of the associated direct and indirect costs, as well as intangible effects such as loss of well-being, independence and excess mortality. The highest costs are caused by productivity losses in VI&B as well as their carers, followed by formal and informal caregiving, recurrent hospitalisations and the use of medical and supportive services in the VI&B. A much larger economic impact was due to intangible effects such as loss of independence, quality of life and excess morbidity. However, these are very difficult to quantify in monetary terms and only a small number of studies attempted this. All highlighted cost components as well as intangible effects which contribute to the overall economic impact of VI&B need to be considered in economic evaluations not only of VI&B but also of interventions aimed at averting these, depending on the focus of the economic evaluation.

A large proportion of the direct costs reported in reviewed studies are not directly related to eye-related medical care, but to falls and other accidents due to visual impairment, exacerbation of diabetes due to a reduced ability to self-manage, depression related to loss of vision and further excess morbidity.23 Drug costs were not a major contributor to overall costs, which is mirrored in studies investigating chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, where—despite its ongoing use—hypoglycaemic drugs constitute only a small proportion of overall direct medical costs.37 The annual mean costs of other potentially incapacitating chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (€5262 or US$6889)37 or the first year after a stroke (US$14 361)38 were much lower for diabetes and similar for the stroke estimate compared to the mean annual costs of severe VI&B.15 23 This is most likely due to the average diabetic not requiring professional caregiving of a scale required during the first year after a stroke or in severely VI&B. In severely VI&B, however, these costs are incurred every year following the loss of vision and do not decrease significantly over the following years unlike the reported annual costs for stroke.38 Javitt et al23 report all direct medical costs caused by visual impairment to amount to US$2.14 million in 2003 in all non-institutionalised Medicare beneficiaries 69 years and older, and postulate a much higher cost for the whole of the US population. With the introduction of anti-Vascular-Endothelial-Growth-Factor treatment for a number of potentially blinding eye diseases such as neovascular age-related macular degeneration, diabetic macular oedema or macular oedema in retinal vein occlusions since all reviewed studies were conducted, the overall direct medical costs associated with visual impairment can be expected to be much higher today. This increase in cost is exacerbated by the ageing of populations in all developed countries as all major blinding diseases are age-related.30

Our finding that indirect costs are much higher than direct costs caused by VI&B is mirrored by virtually all other cost-of-illness studies assessing the economic impact of diseases or impairments which result in absenteeism and reduced ability to work.39 40 Back pain, for example, was found to cause considerable absenteeism and disablement, which—despite its significant hospital cost—lead to indirect costs constituting 93% of the overall costs in 1991 in the Netherlands.40 Even in treatment and healthcare resource intensive chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, indirect costs pose more than half of the overall costs caused by the illness.39

All studies which assessed intangible effects in economic terms reported these to be the largest contributor to the overall economic impact of VI&B. Considering the adverse impact of losing vision on quality of life, independence and the ability to participate in society, this is not surprising. We and others have previously reported that even mild visual impairment (0.3<LogMAR<0.5) has a significant and independent impact on vision-specific functioning.41–43 Similarly, emotional well-being is affected in patients with even mild vision impairment.42 Depression is considered to result in further functional decline in this group by reducing motivation, initiative and resiliency.44–46 Even unilateral vision loss had a measurable impact on falling and some other activities of independent living, with increased odds of having problems in many activities of daily life in a study conducted by Vu et al.34 All this very adversely impacts the ability to participate in society, but also contributes to the considerable economic impact of intangible effects caused by VI&B.

There are several limitations which necessitate a careful interpretation of the overall findings. Using keywords to identify relevant literature always bears the potential of a too narrow focus, and not all the relevant literature may have been included. As we were interested in the economic burden of VI&B in high-income countries, we did not include (uncorrected) refractive error in our search terms as this is mostly a problem of middle-income and low-income countries, and excluded studies conducted in middle-income and low-income countries, which limits our results to high-income countries. Based on the searches conducted, as well as the cross-searching performed based on references, the authors are confident that the vast majority of the relevant literature could be included. To the authors’ knowledge, a standardised quality checklist has not been used to assess economic evaluations of the impact of VI&B prior to inclusion in a systematic review until now. This further increases the overall quality of our review. The study synthesis of the reviewed literature was limited as no two studies used the same methodology, lacking a standardised definition and specification of cost components (see online supplementary appendix 2). Furthermore, no two studies reported exactly the same outcomes or used the same sample population. These problems have been reported for cost-of-illness—or in this case cost-of-impairment—studies in other areas, and adherence to existing cost-of-illness study guidelines is recommended.12 13 47 Unfortunately, none of the reviewed studies seem to have adhered to any of the available international standards, and thus the overall comparability is limited. Similar to cost-of-illness studies in other areas, studies are summarised mostly descriptively or at a high level of aggregation.12 The same applies to the chosen categories of visual impairment used in all studies, which differ considerably and further limit our ability to collate results (table 1).The perspective (affected person, healthcare payer, societal) of the study was only described in a minority of studies, and as highlighted in the results section, most studies were conducted in the USA and Australia, making inferences to other countries and healthcare systems difficult. However, this is the only systematic review of the economic impact of VI&B until now, highlighting the very broad economic impact and outlining the considerable scope that a comprehensive economic evaluation in this area should ideally have.

In conclusion, VI&B cause a considerable economic burden for affected persons, their caregivers and society at large, which increases with the degree of visual impairment for all assessed cost categories as well as intangible effects. This review highlights a large amount of cost categories which should be considered in economic evaluations in eye health, and future cost-of-illness or cost-of-impairment studies should adhere to the available guidelines to improve comparability. The review highlights the considerable amount of resources spent on caring for VI&B persons in the absence of a cure.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KB and CS searched the databases and extracted the references; KB, CS and JK collated the studies; KB, JK and RF drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design of the review and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by the German Research Council (DFG FI 1540/5-5, grant to RPF), by an unconditional grant from Novartis Pharma Germany and by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Clinical Research Excellence #529923—Translational Clinical Research in Major Eye Diseases. CERA receives Operational Infrastructure Support from the Victorian Government. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Finger RP, Fimmers R, Holz FG, et al. Incidence of blindness and severe visual impairment in Germany: projections for 2030. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4381–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, et al. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:514–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor HR, Pezzullo ML, Keeffe JE. The economic impact and cost of visual impairment in Australia. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90:272–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luce BR, Elixhauser A. Estimating costs in the economic evaluation of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1990;6:57–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ament A, Evers S. Cost of illness studies in health care: a comparison of two cases. Health Policy 1993;26:29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmert M, Huber M, Schöffski O. Eine Aggregation von Instrumenten zur Qualitätsbewertung gesundheitsökonomischer Evalutionsstudien. Pharmacoeconomics 2011:11–30 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan RL, Prediger DJ. Coefficient Kappa: some uses, misuses, and alternatives. 1981;6:87–99 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The World Bank: GDP deflator—World development Indicators. Access date 2013-04-08 2013 [cited 2013 8 Apr 2013]. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.KD.ZG/countries.

- 13.Frick KD, Kymes SM, Lee PP, et al. The cost of visual impairment: purposes, perspectives, and guidance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:1801–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OECD Health policies and data: OECD Health Data 2012. 2012

- 15.Bramley T, Peeples P, Walt JG, et al. Impact of vision loss on costs and outcomes in medicare beneficiaries with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:849–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brezin AP, Lafuma A, Fagnani F, et al. Prevalence and burden of self-reported blindness, low vision, and visual impairment in the French community: a nationwide survey. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1117–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou SL, Lamoureux E, Keeffe J. Methods for measuring personal costs associated with vision impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006;13:355–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke P, Gray A, Legood R, et al. The impact of diabetes-related complications on healthcare costs: results from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS Study No. 65). Diabetic Med 2003;20:442–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruess AF, Gordon KD, Bellan L, et al. The cost of vision loss in Canada. 2. Results. Can J Ophthalmol 2011;46:315–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon KD, Cruess AF, Bellan L, et al. The cost of vision loss in Canada. 1. Methodology. Can J Ophthalmol 2011;46:310–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frick KD, Walt JG, Chiang TH, et al. Direct costs of blindness experienced by patients enrolled in managed care. Ophthalmology 2008;115:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frick K, Gower EW, Kempen JH, et al. Economic impact of visual impairment and blindness in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:544–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javitt JC, Zhou Z, Willke RJ. Association between vision loss and higher medical care costs in Medicare beneficiaries costs are greater for those with progressive vision loss. Ophthalmology 2007;114:238–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeffe JE, Chou SL, Lamoureux EL. The cost of care for people with impaired vision in Australia. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:1377–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kymes SM, Plotzke MR, Li JZ, et al. The increased cost of medical services for people diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma: a decision analytic approach. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;150:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lafuma A, Brezin A, Fagnani F, et al. Nonmedical economic consequences attributable to visual impairment: a nation-wide approach in France. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:158–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarty CA, Nanjan MB, Taylor HR. Vision impairment predicts 5 year mortality. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:322–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morse AR, Yatzkan E, Berberich B, et al. Acute care hospital utilization by patients with visual impairment. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:943–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porz G, Scholl HP, Holz FG, et al. [Methods for estimating personal costs of disease using retinal diseases as an example]. Ophthalmologe 2010;107:216–20, 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rein DB, Zhang P, Wirth KE, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:1754–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts CB, Hiratsuka Y, Yamada M, et al. Economic cost of visual impairment in Japan. Arch Ophthalmol 2010;128:766–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmier JK, Covert DW, Matthews GP, et al. Impact of visual impairment on service and device use by individuals with diabetic retinopathy. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:659–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmier JK, Halpern MT, Covert D, et al. Impact of visual impairment on use of caregiving by individuals with age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2006;26:1056–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vu HT, Keeffe JE, McCarty CA, et al. Impact of unilateral and bilateral vision loss on quality of life. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:360–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong EY, Chou SL, Lamoureux EL, et al. Personal costs of visual impairment by different eye diseases and severity of visual loss. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2008;15:339–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood JM, Lacherez P, Black AA, et al. Risk of falls, injurious falls, and other injuries resulting from visual impairment among older adults with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:5088–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koster I, von Ferber L, Ihle P, et al. The cost burden of diabetes mellitus: the evidence from Germany—the CoDiM Study. Diabetologia 2006;49:1498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewey HM, Thrift AG, Mihalopoulos C, et al. Cost of stroke in Australia from a societal perspective: results from the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke 2001;32:2409–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henriksson F, Jonsson B. Diabetes: the cost of illness in Sweden. J Intern Med 1998;244:461–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. A cost-of-illness study of back pain in the Netherlands. Pain 1995;62:233–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finger RP, Fenwick E, Chiang PP, et al. The impact of the severity of vision loss on vision-specific functioning in a German outpatient population—an observational study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;249:1245–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finger RP, Fenwick E, Marella M, et al. The impact of vision impairment on vision-specific quality of life in Germany. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:3613–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamoureux EL, Chong E, Wang JJ, et al. Visual impairment, causes of vision loss, and falls: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:528–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Tasman WS. Effect of depression on vision function in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1041–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, Boerner K, et al. The influence of health, social support quality and rehabilitation on depression among disabled elders. Aging Ment Health 2003;7:342–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tolman J, Hill RD, Kleinschmidt JJ, et al. Psychosocial adaptation to visual impairment and its relationship to depressive affect in older adults with age-related macular degeneration. Gerontologist 2005;45:747–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bloom BS, Bruno DJ, Maman DY, et al. Usefulness of US cost-of-illness studies in healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:207–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.