Abstract

Objective

The improved availability of MRI in medicine has led to an increase in incidental findings. Unexpected brain MRI findings suggestive of multiple sclerosis (MS) without typical symptoms of MS were recently defined as radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS). The prevalence of RIS is uncertain. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of RIS at a university hospital in a region with a high prevalence for MS and describe the long-term prognosis of the identified patients.

Design

Retrospective cohort study conducted in 2012.

Setting

All brain MRI examinations performed at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden during 2001 were retrospectively screened by a single rater for findings fulfilling the Okuda criteria. The sample year was chosen in order to establish the long-term prognosis of the patients identified. The examinations of interest were re-evaluated according to the Barkhof criteria by a neuroradiologist with long experience in MS.

Participants

In total 2105 individuals were included in the study. Ages ranged from 0 to 90 years with a median age of 48 years. Only one patient with RIS was identified, equivalent to a prevalence of 0.05% in the studied population, or 0.15% among patients aged 15–40 years. The patient with RIS developed symptoms consistent with MS within 3 months accompanied with radiological progression and was diagnosed with MS.

Conclusions

RIS, according to present criteria, is an uncommon finding in a tertiary hospital setting in a high-prevalence region for MS where awareness and clinical suspicion of MS is common. In order to study the prognosis of RIS, multicentre studies, or case–control studies are recommended.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study reporting on the frequency of radiologically isolated syndrome in a high-prevalence region for multiple sclerosis.

The study was a systematic re-evaluation of a yearly sample at a large university clinic.

The retrospective nature of the study gives the possibility to report on the long-term prognosis for the patients, but also gives rise to losses to follow-up.

The generalisability of the results to non-tertiary hospital settings and to regions with a lower prevalence of multiple sclerosis is limited.

Introduction

MRI has revolutionised our ability to image the central nervous system and it has become readily accessible in clinical practice. With the improved availability and sensitivity of MRI there is an increase in incidental findings.1 In 2009, Okuda et al2 defined incidental MRI findings suggestive of multiple sclerosis (MS) without typical MS symptoms as radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS). This has led to an increased awareness of this condition and a convergence in terminology.3

Since the definition of RIS, studies by several groups have shown that there is a close association between RIS and MS. Patients with RIS often have a subclinical cognitive impairment with a similar test profile of deficits compared with patients with MS.4–6 The association of RIS and MS is also strengthened in that both patient groups show similarities in both qualitative and quantitative MRI measurements.6–8 There are case reports with follow-ups of up to 10 years,4 9 10 and the range of mean follow-up times in the published cohorts are 2.4–7 years.2 11–17 These studies show that roughly two-thirds progress radiologically and one-third develop clinical symptoms, and thereby convert to clinically isolated syndrome or MS, during their follow-up times.3 This suggests that RIS in some cases may be considered to be preclinical MS. The patients with RIS are therefore of particular interest to study in a pathophysiological aspect since it may shed light on early changes that precedes the onset of classical MS symptoms.

Headache is the most common reason for performing the initial MRI unveiling RIS, but it is unclear if there is a causative relationship between the incidental MRI findings and the headaches.3 Recently a study by Liu et al showed that among patients undergoing MRI of the brain due to headaches, MRI findings fulfilling the Barkhof criteria are common. Depending on the definition of juxtacortical and periventricular, 2.4–7.1% of the patients fulfilled the Barkhof criteria.18

Incidental MS findings are previously known from autopsy studies from the late 20th century indicating a frequency of unexpected postmortem MS findings in the range 0.08–0.2%.19–22 The incidence and prevalence of the newly defined RIS is, however, currently unknown.3 In 2009 Morris et al1 published a meta-analysis of 16 studies including 15 559 healthy control participants that reported nine cases of ‘definite demyelination’ and four cases of ‘possible demyelination’ corresponding to a frequency of 0.06% and 0.03%, respectively. There is unfortunately no report on the clinical history or neurological examination of these cases as to why the results cannot be assumed to reflect RIS. Instead the results of five original articles, identified as the most relevant, are described below.

An American study published in 1996, described 23 patients with MRI findings highly suggestive of MS (according to Paty's classification) in a population of 2783 psychiatric patients. However, 13 patients had neurological symptoms that were not further specified, which gives a possible asymptomatic frequency of roughly 0.4%. It is unknown if these patients had any neurological findings that would exclude them from an RIS diagnosis.23 The results are nonetheless interesting since psychiatric symptoms have frequently been reported as the original indication for performing the MRI examination that unveiled the RIS.3 A second American study published in 1999 showed that among 1000 asymptomatic participants, there were 3 persons (0.3%) with findings classified as possible demyelinating disease.24 A German study published in 2006 described a cohort of 2536 young male military recruits in which 1 person (0.04%) had findings suggestive of demyelinating disease, but it is not specified if this person had any neurological symptoms or findings.25 A second German study was published in 2010, which showed that of 206 healthy young volunteers 2 (1%) had multiple white matter lesions, but it is unclear whether the findings fulfilled the Barkhof criteria.26

The first study reporting on the frequency of RIS since its definition was a hospital-based study from Pakistan published in 2011. It revealed that of 864 persons in the ages 15–40 years there were six cases (0.7%) of incidental MRI findings suggestive of MS in patients without relapsing neurological symptoms or pathological neurological findings.27 This study reported a surprisingly high frequency of such findings in a region with a low prevalence of MS (<5/100 000 population).28 In comparison the estimated prevalence of MS in Sweden, where the present study was conducted, is 189/100 000 population.29 Recently a second study using the RIS criteria was published in 2013 that demonstrated the frequency of RIS findings in asymptomatic relatives to MS patients and healthy controls. It showed that 2 of 68 (2.9%) healthy relatives of MS patients and 2 of 82 (2.4%) of the healthy controls fulfilled the Okuda criteria.30

In conclusion there has not been any study reporting on the hospital-based prevalence of RIS in a high-prevalence region for MS since the definition of RIS. This study aims to clarify in what frequency RIS findings can be expected in a tertiary hospital setting in a high-prevalence region for MS and depict the long-term prognosis of RIS in the patients identified.

Methods

Study population and ethical approval

The study sample in this retrospective study conducted in 2012 is based on the digital radiological information system and digital patient charts at Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge (formerly Huddinge University Hospital), Stockholm, Sweden. The hospital is a tertiary referral hospital for the greater southern Stockholm area with a population of 800 000 inhabitants. Although the study was conducted in 2012, the sample year was chosen to be 2001, when both the patient charts and the radiological data were fully digitalised, in order to be able to show the natural long-term prognosis over the past 11 years for any RIS cases identified. All persons undergoing a brain MRI at the hospital during the sample year were included in the study. The written informed consent was obtained according to the approval in those cases where more information was necessary through access of the clinical patient charts.

Screening method

The screening of the study population was made systematically by one physician at the radiology department with previous experience of radiological research (TG). All documentation from the MRI examinations from 2001 was available to the screener and read to full extent. The material included both the query, the clinical information in the referral (clinical history, symptoms and findings) as well as the radiological findings according to the regular clinical radiological assessment.

MRI examinations

All MRI examinations were performed in the regular clinical setting in one of two 1.5 T MRI machines, Siemens Magnetom Vision and Symphony (Siemens Medical Systems GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). The MRI examinations were performed according to standard clinical protocols depending on the original clinical query and white matter anomalies were in most cases further characterised with the standardised MS MRI protocol used at the clinic described in table 1.

Table 1.

MRI parameters of the standardised MS protocol

| Sequence | Plane | SLT (mm) | TR (ms) | TE (ms) | TI (ms) | FA (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 MPRAGE | Axial | 1.5 | 13.5 | 7 | 300 | 15 |

| PD TSE | Axial | 3.0 | 4761 | 22 | – | 180 |

| T2 TSE | Axial | 3.0 | 4761 | 90 | – | 180 |

| T2 TSE* | Sagittal | 4.0 | 3500 | 96 | – | 180 |

| FLAIR* | Axial | 5.0 | 9000 | 110 | 2500 | 180 |

| T1 SE* | Axial | 5.0 | 570 | 14 | – | 90 |

*Acquired postgadolinium-DTPA contrast media.

FA, flip angle; FLAIR, fluid attenuated inversion recovery; MPRAGE, three-dimensional magnetisation prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo; MS, multiple sclerosis; PD, proton density; SE, spin echo; SLT, slice thickness; TE, echo time; TI, inversion time; TR, repetition time; TSE, turbo spin echo.

Radiological assessment

All examinations had been reviewed, signed and contra-signed as part of the regular clinical radiological routine. At least one of the clinical reviewers was a specialist in neuroradiology. The examinations identified with possible RIS findings in the screening process were re-evaluated according to the Barkhof criteria by another neuroradiologist (JM) with long experience of classifying MS-like findings.

Clinical assessment

The referring doctor conducted the initial clinical assessments. All patients that were identified as possible RIS cases in the screening had been examined by a neurologists as part of the following clinical investigation. All patients diagnosed with MS received their diagnosis according to contemporaneous diagnostic criteria after careful investigation lead by a neurologist with experience of MS.

Results

Prevalence of RIS

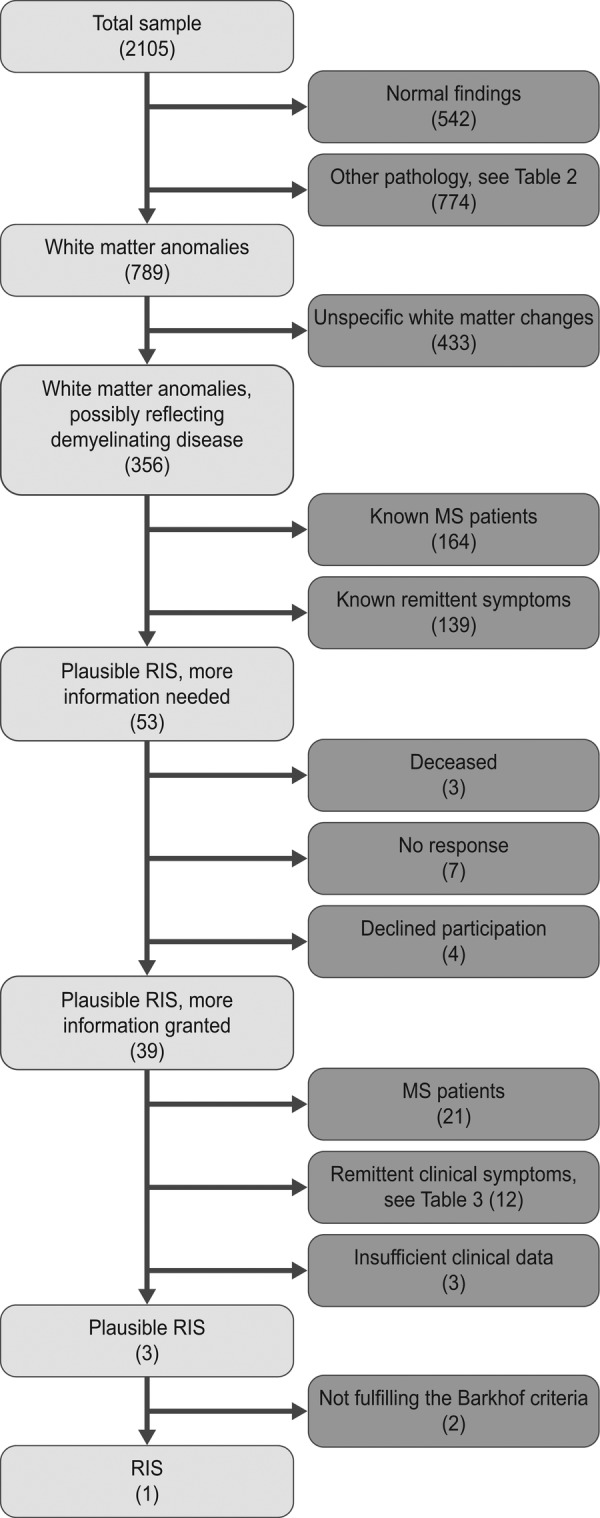

During the year of 2001 a total of 2105 individuals had at least one MRI examination of the brain at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden. Among the patients there were 903 men (43%) and 1202 women (57%) with an age span of 0–90 years with 669 persons being between 15 and 40 years of age. The mean age was 46.2 years and median age was 48 years. The following results are also schematically described in figure 1. Of all patients 542 had normal findings. The spectrum of findings is presented in table 2. Common findings besides white matter changes were tumours, atrophy, infarctions and sinusitis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the screening process to identify patients with possible radiologically isolated syndrome.

Table 2.

Overview of MRI findings (n)

| Within normal limits | 542 |

| Cerebrovascular disorders | 326 |

| Aneurysm | 8 |

| Carotid dissection or occlusion | 12 |

| Cavernous malformation | 19 |

| Cerebral contusions | 4 |

| Cortical infarction | 89 |

| Developmental venous anomaly | 29 |

| Lacunar infarction | 133 |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 15 |

| Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis | 5 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 3 |

| Subdural haematoma or hygroma | 6 |

| Other | 3 |

| White matter and neurodegenerative disorders | 1143 |

| Atrophy | 285 |

| Basal ganglia disorders | 12 |

| Hydrocefalus | 20 |

| Marked perivascular spaces | 37 |

| Possibly inflammatory white matter changes | 356 |

| Unspecific or degenerative white matter changes | 433 |

| Infectious, inflammatory and metabolic disorders | 88 |

| Cerebral abscess | 7 |

| Congenital metabolic disorders | 4 |

| Encephalitis | 10 |

| Meningitis | 15 |

| Optical neuritis | 37 |

| Vasculitis | 4 |

| Other | 11 |

| Neoplasms | 311 |

| Acoustic neuroma | 19 |

| Glioma | 21 |

| Meningioma | 44 |

| Metastasis | 18 |

| Pituitary adenoma | 31 |

| Unspecified or other type of neoplasm | 46 |

| Cysts and malformations | 74 |

| Arachnoid cyst | 24 |

| Empty sella | 9 |

| Malformation or dysplasia | 16 |

| Parenchymal cyst | 5 |

| Pineal cyst | 13 |

| Pituitary cyst | 7 |

| Sinonasal and orbital disorders | 191 |

| Sinusitis | 164 |

| Mastoiditis | 23 |

| Other | 4 |

In total 789 patients had white matter anomalies (not involving those caused by other diseases). Of these patients, 433 had unspecific white matter changes that did not fulfil the Barkhof criteria (solitary findings) or had a more likely explanation; such as an ischaemic-degenerative pattern in elderly and/or patients with known severe cardiovascular disease. Of the 356 patients with white matter changes possibly reflecting demyelinating disease, 158 patients were known to have MS and 6 received their MS diagnosis as part of the investigation in question. Of the 192 remaining patients 139 were reported to have apparent neurological symptoms in the referral that would exclude the findings from being classified as RIS according to the B criteria in the Okuda classification, but where it was unclear if they had already gotten a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome or MS. After this screening only 53 patients remained with findings that were plausible RIS but where more clinical information was needed. In compliance with the ethical approval these patients were asked for written informed consent in order for us to evaluate their clinical patient charts.

Of these 53 patients where further information was needed, 3 patients were deceased, 7 did not respond and 4 declined participation. The patient charts of the remaining 39 persons that gave their informed consent were then examined in order to better understand the patients’ clinical history, symptoms and neurological findings. This additional information revealed that 21 had been diagnosed with MS. Another 12 had intermittent clinical symptoms dismissing an RIS classification, presented in table 3, but where the patients had not yet received a diagnosis of MS. In three cases there were insufficient clinical data to draw a conclusion. In the end, three patients with plausible RIS remained and after neuroradiological assessment one patient was classified as having RIS. This is equivalent to a prevalence of 0.05% in the studied population and 0.15% among the patients in the ages of 15–40 years.

Table 3.

Presenting symptoms in the 12 patients not classified as RIS

| Sex | Age (years) | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| F | 25 | Optical neuritis, Lhermitte's sign |

| F | 26 | Diplopia, hemiparesis |

| F | 39 | Optical neuritis, facial hemidysesthesia |

| F | 43 | Optical neuritis |

| F | 47 | Recurrent hemidysesthesia |

| F | 58 | Trigeminal neuralgia |

| F | 62 | Hemidysesthesia, facial paralysis |

| F | 62 | Hemidysesthesia |

| M | 18 | Severe vertigo, ataxia |

| M | 18 | Lhermitte's sign |

| M | 27 | Diplopia, vertigo, dysesthesia |

| M | 44 | Hypesthesia |

F, female; M, male; RIS, radiologically isolated syndrome.

Case description

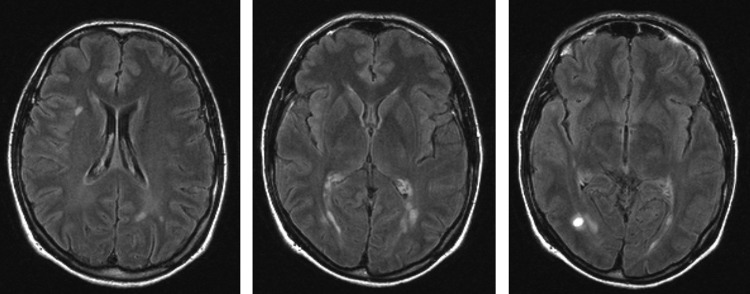

The patient with RIS was a 43-year-old woman without any neurological symptoms or any history of neurological disorders except for migraine since more than 10 years. A neurological examination did not reveal any pathological findings. She had good effect of triptanes. Owing to her long history of migraine and still frequent attacks she was referred for MRI of the brain in February 2001. The scan showed 15 supratentorial T2 lesions, of which 12 were periventricular and 2 were juxtacortical. Gadolinium-enhanced sequences showed enhancement in one of the lesions. Thus three of the four of the Barkhof criteria were fulfilled.31 Images obtained from this patient can be seen in figure 2. Owing to the MRI findings, she was referred to a neurologist in March where a second neurological examination was normal. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed oligoclonal bands and an elevated IgG index. In May she returned to the neurological clinic due to a sudden onset of intermittent bilateral symptoms in arms and hands. A new neurological examination revealed bilateral tremor and dysmetria. A new MRI in June showed three new non-enhancing supratentorial lesions. She was diagnosed with MS and at a follow-up in September the symptoms in the upper extremities had worsened. She received prednisolone treatment and was started on interferon β therapy. In November she had Lhermitte's sign and MRI showed a cervical spine lesion. Except for one occurrence of lower extremity symptoms in 2005, she has remained relapse free as of the latest neurological follow-up in March 2013.

Figure 2.

Axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery images of the identified radiologically isolated syndrome patient illustrating the multiple T2 hyperintensities and the contrast-enhancing lesion in the far right image.

Discussion

This study showed that RIS, according to present stringent criteria, is an uncommon finding, in a tertiary radiological clinic in a region with a high prevalence of MS, where awareness and clinical suspicion of MS is common.29 The RIS frequency of 0.05% is in alignment with previous anatomopathological studies and earlier MRI studies have shown that ‘incidental’ or ‘asymptomatic’ MS is relatively uncommon.19–26 The only hospital-based reported frequency of RIS since its definition, 0.7%, comes from a report from the Karachi region of Pakistan.27 In contrast, the current study reports a frequency of RIS of 0.15% in the same age group. Although the studies are not directly comparable due to dissimilarities in methodology, it is of interest to consider the difference in results further. A possible explanation may be the high awareness of MS in Sweden and frequent clinical suspicion when referring patients for MRI. The results could possibly also be affected by the fact that a majority of the referrals to the radiological clinic participating in this study comes from the in-hospital clinics, while patients initially seeking their family practitioner might have been referred to a non-tertiary radiological clinic for MRI. How the fact that the study site is a tertiary setting has affected the reported prevalence is therefore hard to appreciate. Another explanation for the difference might be that the study from Pakistan was a semiretrospective and semiprospective study, which might have been more effective in identifying patients with these findings and suffering from less losses to follow-up. In the study from Pakistan there were also fewer patients examined in a more densely populated area, likely mirroring a lower availability of MRI in the Karachi region than in the Stockholm region, perhaps making the patients who were examined with MRI of the brain in Karachi more likely to have findings. The published RIS cohorts are samples from Brazil, France, Italy, Spain, Turkey and the USA,2 7 11–17 regions that vary from low to high prevalence.32 It would be of interest to further evaluate the RIS prevalence in relation to the global MS prevalence.

Interestingly, the study published by Gabelic et al30 shows that 2.9% of the healthy relatives of MS patients and 2.4% of the healthy controls in their study fulfilled Okuda's RIS criteria. This might indicate that the frequency of RIS findings would paradoxically be higher in the general population than found in the current study. However, differences in methodologies and demography of the research participants limit the comparability of the current study to Gabelic's work. The studies were not performed in the same region and with different aims. While this study aimed to describe the hospital-based frequency of RIS without limitations in terms of age groups, Gabelic's study was performed in a different country and studied the frequency of RIS in healthy hospital personnel and volunteers recruited through newspaper advertisement within a homogenous age group with a mean age of 40 years.

A limitation of this study is the retrospective design with a single rater that may have led to patients being missed in the screening although a systematic approach was taken. By relying on the clinical evaluations in the screening process it is possible that patients with findings fulfilling the Barkhof criteria were missed. We believe that such gross errors are unlikely since at least one neuroradiologist and in total usually two radiologists evaluated all examinations as part of the clinical diagnostics. This being said, any patient missed would affect the reported frequency significantly due to the low prevalence of RIS. In terms of losses to follow-up, assuming that the frequency of RIS was the same in the 17 plausible RIS patients lost to follow-up as in those with all data available (1 case of RIS in 36 patients with plausible RIS), this would be equivalent to 1/36×17=0.47. This would increase the RIS frequency to 0.07%, or double the reported frequency to 0.1%, if rounded up to one patient. It is also unexpected that no elderly patients were classified as RIS since the presence of asymptomatic white matter lesions increase with age.33 This might be due to the clinical information being available in the screening process, making it more likely to classify these white matter changes as ischaemic-degenerative. The study period was chosen to be the year 2001 in order to be able to show the natural long-term prognosis for the RIS cases identified with a potential follow-up period of 11 years. The reasoning for this was that regarding the published RIS cohorts, especially the retrospective cohorts, it is often unclear how the patients were initially identified. The hypothesis was therefore that patients with RIS that do not progress clinically are less likely to be noticed in the clinical setting, decreasing the chance of being included in a cohort, giving the observed cohort a worse prognosis. The study design did unfortunately not prove very helpful since only one case was identified, which limits the possibility of studying the prognosis. Although the study was conducted in 2001, it was conducted on modern 1.5 T MRI machines why the low frequency of RIS findings is hardly explained by technical reasons.

In conclusion this study suggests that RIS, according to present stringent criteria, is an uncommon finding in a tertiary hospital setting in a region with a high prevalence of MS. In order to more accurately determine the frequency of RIS in relation to MS prevalence, non-selected populations in large prospective studies actively involving both radiologists and neurologists are needed. In order to be able to study the prognosis of these patients large multicentre studies or case–control studies are recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Helena Forssell and Karin Kjellsdotter for their administrative support. They would also like to acknowledge Sara Shams for valuable comments on the manuscript for this article.

Footnotes

Contributors: TG initiated the study, designed data collection tools, performed the screening of all MRI examinations, monitored data collection, and drafted the paper. He is guarantor. JM performed neuroradiological image analysis. TG, JM, MKW, PA and SF all conceived and designed the study, analysed the data and revised the paper.

Funding: This research was funded by from Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF grant 20120213).

Competing interests: SF has received honoraria for lectures or educational activities from Allergan, Bayer, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the regional ethical review board in Stockholm at Karolinska Institutet.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT, Jret al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2009;339:b3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okuda DT, Mowry EM, Beheshtian A, et al. Incidental MRI anomalies suggestive of multiple sclerosis: the radiologically isolated syndrome [correction appears in Neurology. 2009;72:1284]. Neurology 2009;72:800–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granberg T, Martola J, Kristoffersen-Wiberg M, et al. Radiologically isolated syndrome—incidental magnetic resonance imaging findings suggestive of multiple sclerosis, a systematic review. Mult Scler 2013;19:271–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakiki B, Goretti B, Portaccio E, et al. ‘Subclinical MS’: follow-up of four cases. Eur J Neurol 2008;15:858–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebrun C, Blanc F, Brassat D, et al. Cognitive function in radiologically isolated syndrome. Mult Scler 2010;16:919–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amato MP, Hakiki B, Goretti B, et al. Association of MRI metrics and cognitive impairment in radiologically isolated syndromes. Neurology 2012;78:309–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Stefano N, Stromillo ML, Rossi F, et al. Improving the characterization of radiologically isolated syndrome suggestive of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e19452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stromillo ML, Giorgio A, Rossi F, et al. Brain metabolic changes suggestive of axonal damage in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2013;80:2090–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonnell GV, Cabrera-Gomez J, Calne DB, et al. Clinical presentation of primary progressive multiple sclerosis 10 years after the incidental finding of typical magnetic resonance imaging brain lesions: the subclinical stage of primary progressive multiple sclerosis may last 10 years. Mult Scler 2003;9:204–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spain R, Bourdette D. The radiologically isolated syndrome: look (again) before you treat. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2011;11:498–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebrun C, Bensa C, Debouverie M, et al. Unexpected multiple sclerosis: follow-up of 30 patients with magnetic resonance imaging and clinical conversion profile. J Neurol Neurosurg Ps 2008;79:195–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebrun C, Bensa C, Debouverie M, et al. Association between clinical conversion to multiple sclerosis in radiologically isolated syndrome and magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid, and visual evoked potential: follow-up of 70 patients. Arch Neurol 2009;66:841–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siva A, Saip S, Altintas A, et al. Multiple sclerosis risk in radiologically uncovered asymptomatic possible inflammatory-demyelinating disease. Mult Scler 2009;15:918–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sierra-Marcos A, Mitjana R, Castilló J, et al. [Demyelinating lesions as incidental findings in magnetic resonance imaging: a study of 11 cases with clinico-radiological follow-up and a review of the literature]. (In Spanish). Rev Neurol 2010;51:129–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuda DT, Mowry EM, Cree BAC, et al. Asymptomatic spinal cord lesions predict disease progression in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2011;76:686–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maia ACM, Jr, da Rocha AJ, Barros BR, et al. Incidental demyelinating inflammatory lesions in asymptomatic patients: a Brazilian cohort with radiologically isolated syndrome and a critical review of current literature. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012;70:5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebrun C, Page EL, Kantarci O, et al. Impact of pregnancy on conversion to clinically isolated syndrome in a radiologically isolated syndrome cohort. Mult Scler 2012;18:1297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Kullnat J, Bourdette D, et al. Prevalence of brain magnetic resonance imaging meeting Barkhof and McDonald criteria for dissemination in space among headache patients. Mult Scler 2013;19:1101–5 Published Online First: 4 February 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgi W. [Multiple sclerosis. Anatomopathological findings of multiple sclerosis in diseases not clinically diagnosed]. (In German). Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1961;91:605–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert JJ, Sadler M. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1983;40:533–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engell T. A clinical patho-anatomical study of clinically silent multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 1989;79:428–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johannsen LG, Stenager E, Jensen K. Clinically unexpected multiple sclerosis in patients with mental disorders. A series of 7301 psychiatric autopsies. Acta Neurol Belg 1996;96:62–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyoo IK, Seol HY, Byun HS, et al. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996;8:54–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzman GLDA. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging from 1000 asymptomatic volunteers. JAMA 1999;282:36–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber F, Knopf H. Incidental findings in magnetic resonance imaging of the brains of healthy young men. J Neurol Sci 2006;240:81–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartwigsen G, Siebner HR, Deuschl G, et al. Incidental findings are frequent in young healthy individuals undergoing magnetic resonance imaging in brain research imaging studies. J Comput Assist Tomo 2010;34:596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasay M, Rizvi F, Azeemuddin M, et al. Incidental MRI lesions suggestive of multiple sclerosis in asymptomatic patients in Karachi, Pakistan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:83–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasay M, Khatri IA, Khealani B, et al. MS in Asian countries. Int MS J 2006;13:59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahlgren C, Odén A, Lycke J. High nationwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Mult Scler 2011;17:901–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabelic T, Ramasamy DP, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Prevalence of Radiologically Isolated Syndrome and White Matter Signal Abnormalities in Healthy Relatives of Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Am J Neuroradiol Published Online First: 25 July 2013.10.3174/ajnr.A3653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, et al. Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain 1997;120:2059–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dua T. Atlas: multiple sclerosis resources in the world. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Multiple Sclerosis International Federation, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1821–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.