Abstract

Tumor induced osteomalacia (TIO) or oncogenic osteomalacia is a rare condition associated with small tumor that secretes one of the phosphaturic hormones, i.e., fibroblast growth factor 23, resulting in abnormal phosphate metabolism. Patients may present with non-specific symptoms leading to delay in the diagnosis. Extensive skeletal involvement is frequently seen due to delay in the diagnosis and treatment. The small sized tumor and unexpected location make the identification of tumor difficult even after diagnosis of osteogenic osteomalacia. The bone scan done for the skeletal involvement may show the presence of metabolic features and the scan findings are a sensitive indicator of metabolic bone disorders. We present the bone scan findings in three patients diagnosed to have TIO.

Keywords: Bone scan, fibroblast growth factor 23, hypophosphatemia, tumor induced osteomalacia

INTRODUCTION

Osteomalacia is a metabolic bone disorder characterized by impaired mineralization. It is a rarely encountered disease in the present scenario. Tumor induced osteomalacia (TIO) also known as osteogenic osteomalacia, is even rarer clinical entity. These patients usually present with bony pains and weakness of long duration. There is often delay in the diagnosis as generalized symptoms of this condition are not attributable to any specific cause. The biochemical parameters may indicate it to be of metabolic in nature. TIO is characterized with hypophosphatemia, hyperphosphaturia and osteomalacia secondary to tumor.[1] These tumors are of mesenchymal origin and have high vascularity. The surgical resections of these tumors result in relief with resolution of disease.[2] Patients may be asked to undergo bone scan for generalized bony pain and weakness to establish the cause of presenting symptoms. Because of rarity of this tumor, the typical findings seen on bone scan are rarely reported. We present the bone scan findings in three proven cases of TIO located with the help of functional and morphological imaging and confirmed histopathology of resected tumors.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

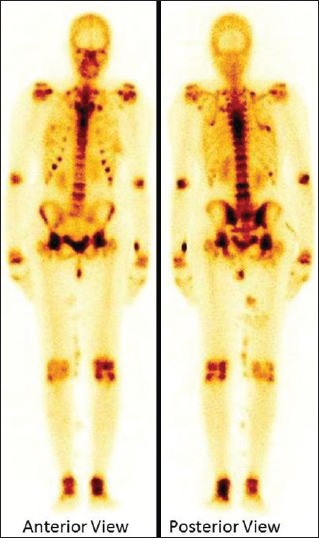

A 32-year-old female patient presented to our hospital with a history of progressive, generalized weakness and bony pain of 1½ year duration, after having unsuccessful treatment at different hospitals. Her biochemical report revealed low serum phosphate level with elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) (452.6 RU/ml) and alkaline phosphatase level while other investigations were within the normal limits. She was subjected to bone scan to rule out metabolic bone disorders and assess the secondary bony changes. Bone scan was performed after 4 h of intravenous injection of 20 mCi of technetium 99m methylene diphosphonate. The bone scan demonstrated increased radiotracer uptake over the mandible, ribs, vertebrae and sternum suggestive of metabolic bone disease. There were features of prominent costochondral beadings and increased tracer uptake over multiple growth plates [Figure 1]. The TIO has been established on subsequent imaging followed by excision of tumor that came out to ameloblastic fibroma.

Figure 1.

Technetium 99m methylene diphosphonate whole body bone scan showing increased radiotracer uptake over the mandible, ribs, vertebrae and sternum suggestive of metabolic bone disease. Prominent costochondral beadings and increased tracer uptake over multiple growth plates are also noted

Case 2

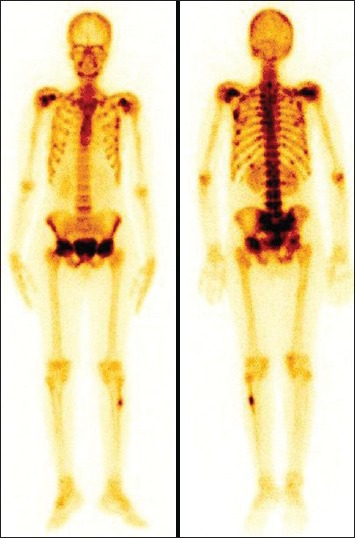

A 26-year-old female patient presented with a history of proximal muscle weakness, low backache and pain both lower limbs of 1 year duration, more so for last 3 months. The provisional diagnosis of hypophosphatemic rickets secondary to TIO was made on the basis of biochemical and imaging findings. The FGF23 (918.2 RU/ml) and alkaline phosphatase were markedly elevated and low phosphorus level. The bone scan revealed bilateral multiple ribs, bilateral shoulders, acetabulum and femoral heads and mild increased focal uptake in right mid foot focally. In addition, the delayed bone scan revealed increased focal uptake in left proximal fibula (also noticed on flow and pool phases) however that was not related to metabolic pattern [Figure 2]. Finally, patient turned out to be a case of TIO. The tumor was excised and histopathology revealed it to be suspicious of mesenchymal tumor.

Figure 2.

Whole body bone scan showing increased uptake in left proximal fibula (focal), bilateral multiple ribs, bilateral shoulder, acetabulum and femoral heads and mildly increased focal uptake in right mid foot

Case 3

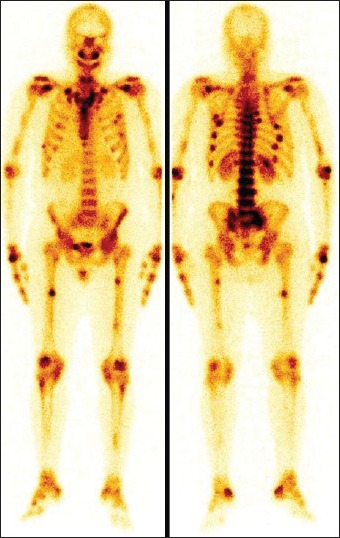

A 34-year-old female presented with progressive weakness in proximal muscles. Her biochemical profile revealed low phosphorus, elevated FGF23 level (147.9 RU/ml) and the rest were within the normal limits. She was diagnosed to be suffering with severe hypophosphatemic osteomalacia. Whole body bone scan showed increased tracer uptake in bilateral maxillary bone, bilateral shoulder, wrist, sternoclavicular, knee and ankle joints, multiple ribs and mid shaft of bilateral femora [Figure 3]. The tumor was localized on functional imaging. It was resected out with histopathology report consistent of mesenchymal tumor and resulting in significant relief of symptoms post-operatively.

Figure 3.

Whole body bone scan shows increased tracer uptake in bilateral maxillary bones, bilateral shoulder, wrist, sternoclavicular, knee and ankle joints, multiple ribs and mid shaft of bilateral femora (pseudofractures)

DISCUSSION

TIO is a rare clinical entity with only few 100 cases published so far. These tumors are very small in size and generally slow growing. They may be located in the unusual sites ranging from head to toe and may arise from bone or soft-tissue.[3] Patients of TIO present with vague symptoms of generalized body ache, muscular weakness and bone or muscle tenderness etc., Patient may become bed ridden if diagnosis and treatment is delayed. Majority of the tumor causing osteomalacia cases are of benign in nature and rarely metastasize to distant organs.[4] These tumors secrete phosphaturic substances that inhibit renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate and FGF23 is one of them resulting in the abnormal phosphate metabolism.[5] The presence of renal phosphate wasting in the patient as the etiology for hypophosphatemia suggests the possibility of the TIO. The biochemical parameters may reveal elevated plasma FGF23, low or inappropriately normal 1,25 vitamin D, normal calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, but PTH can be high, reflecting secondary hyperparathyroidism, which is a normal response to low 1,25 vitamin D caused by elevated FGF23 and alkaline phosphatase.[6] Once FGF23-dependent phosphate wasting disorder due to TIO is made, thorough physical examination should be done to look for these tumors which may be found in subcutaneous tissue as well as in the skeletal system.[7,8]

The morphological and functional imaging modalities including computed tomography (CT), whole body magnetic resonance imaging, fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, In-111 Octreotide and Ga-68Dotatate PET/CT[4,9,10,11] have been used to localize the tumor. Many times, the imaging may fail to localize them due to their small size and unusual location. Histopathology of the resected tumor is required for definitive diagnosis and the complete resection lead to cure of the patient with normalization of phosphate and FGF23 levels.[12] X-ray confirmation of osteomalacia is difficult with non-specific changes such as osteopenia. The radiologic findings in case of osteomalacia would be increased concentration of osteoid formation with impaired mineralization. Pseudofractures or Looser's zones are insufficiency stress fractures that may appear before the other radiologic changes in osteomalacia.[13] Pseudofractures are typical bilateral, more or less symmetrical and tend to occur at specific sites. Their presence has been considered to be pathognomic for the presence of osteomalacia.[14,15]

Bone scan is highly sensitive imaging modality for detecting the skeletal metastases. However, its use is limited in metabolic bone disease and usually detects the affected bones due to TIO rather than the primary tumor.[16] The bone scan findings of TIO may mimic metastatic bone lesions making it difficult to differentiate from metastatic disease. The whole body bone scan in TIO may demonstrate typical findings of osteomalacia, i.e. widening of the mandible, rachitic rosary sign, tie sign of sternum, pseuodofracture and prominent epiphyses of knees suggesting it to be metabolic in nature.[17] There are very few descriptions of bone scan pattern in TIO in the literature so far. In two case reports of TIO, the bone scans demonstrated multiple foci of increased tracer uptake.[15,18] It is worth to note that the uptake pattern in bone scan in TIO and osteomalacia secondary to other causes like malabsorption, renal failure, vitamin D deficiency and drugs is almost similar.[16]

Fogelman et al.,[19] described the findings seen in bone scans in the 10 patients with osteomalacia from various causes. They have described various features observed in the bone scan: Increased tracer uptake by the axial skeleton, long bones and wrists, prominent calvarium and mandible, beading of the costochondral junction, faint kidneys, pseudofracture in the form of focal abnormalities and tie sternum. The bone to soft tissue ratio is significantly high in osteomalacia. The increased tracer uptake in long bones and wrist joints along with prominence of calvarium and mandible are some of the most consistent abnormal finding in osteomalacia, but may also be seen in primary hyperparathyroidism. The presence of beading of the costochondral junction and tie sternum may be non-specific and can be seen in patients with renal osteodystrophy. These non-specific features strongly suggest a metabolic disorder, in the presence of clinical and biochemical findings.

Findings of increased tracer uptake at costochondral junctions and of the growth plate in adult skeleton (sort of adult rachitic rosary and pseudo reactivation of growth plates) have been described in the bone scans done in patients with TIO.[4] However, the pathophysiology underlying this phenomenon is not clear. Patients may have variable findings on bone scan depending upon the severity and duration of the disease. It would be rather unusual that all the typical findings be present in the cases of metabolic bone disease. The bone scan is useful in demonstrating the pattern of the metabolic bone disease and it may be helpful in making the correct diagnosis or treatment monitoring with the follow-up scans.

CONCLUSION

In the conclusion, the objective of this article is to present the typical bone scan features seen on bone scan in rarely reported TIO cases, which might be helpful in arriving at the diagnosis or serve as the basis for the follow-up scan after therapeutic intervention.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cai Q, Hodgson SF, Kao PC, Lennon VA, Klee GG, Zinsmiester AR, et al. Brief report: Inhibition of renal phosphate by a tumor product in a patient with oncogenic osteomalacia. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1645–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan EA, Reiss E. Oncogenous osteomalacia. Review of the world literature of 42 cases and report of two new cases. Am J Med. 1984;77:501–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukumoto S, Takeuchi Y, Nagano A, Fujita T. Diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging skeletal survey in a patient with oncogenic osteomalacia. Bone. 1999;25:375–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong WH, Molinolo AA, Chen CC, Collins MT. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:R53–77. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brame LA, White KE, Econs MJ. Renal phosphate wasting disorders: Clinical features and pathogenesis. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:39–47. doi: 10.1053/j.semnephrol.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drezner MK. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2001;2:175–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1010006811394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colt E, Gopan T, Chong HS. Oncogenic osteomalacia cured by removal of an organized hematoma. Endocr Pract. 2005;11:190–3. doi: 10.4158/EP.11.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun KI, Kim DH, Pyo SW. A phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the floor of the mouth with oncogenic osteomalacia: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:402–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupond JL, Mahammedi H, Prié D, Collin F, Gil H, Blagosklonov O, et al. Oncogenic osteomalacia: Diagnostic importance of fibroblast growth factor 23 and F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scan for the diagnosis and follow-up in one case. Bone. 2005;36:375–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duet M, Kerkeni S, Sfar R, Bazille C, Lioté F, Orcel P. Clinical impact of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in the management of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:752–6. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31818866bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Falck C, Rodt T, Rosenthal H, Länger F, Goesling T, Knapp WH, et al. (68) Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT for the detection of a mesenchymal tumor causing oncogenic osteomalacia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1034. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0755-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clunie GP, Fox PE, Stamp TC. Four cases of acquired hypophosphataemic (‘oncogenic’) osteomalacia. Problems of diagnosis, treatment and long-term management. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1415–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinbach HL, Noetzli M. Roentgen appearance of the skeleton in osteomalacia and rickets. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1964;91:955–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinbach HL, Kolb FO, Gilfillan R. A mechanism of the production of pseudofractures in osteomalacia (Milkman's syndrome) Radiology. 1954;62:388–95. doi: 10.1148/62.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitt MJ. Rickets and osteomalacia are still around. Radiol Clin North Am. 1991;29:97–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HK, Sung WW, Solodnik P, Shimshi M. Bone scan in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:247–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rai GS, Webster SG, Wraight EP. Isotopic scanning of bone in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29:45–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 52-1989. A 63-year-old man with osteomalacia and the later development of a right nasal mass. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1812–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912283212607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogelman I, McKillop JH, Bessent RG, Boyle IT, Turner JG, Greig WR. The role of bone scanning in osteomalacia. J Nucl Med. 1978;19:245–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]