Abstract

Introduction

Standard therapy for limited stage small cell lung cancer (L-SCLC) is concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy followed by prophylactic cranial radiotherapy. Although many consider the standard radiotherapy regimen to be 45 Gray (Gy) in 1.5 Gy twice-daily fractions, this has failed to gain widespread acceptance. We pooled data for patients assigned to receive daily radiotherapy to 70 Gy on three consecutive prospective CALGB L-SCLC cancer trials and report the results here.

Methods

All patients on consecutive CALGB L-SCLC trials (39808, 30002, and 30206) utilizing high dose daily radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy were included, and analyzed for toxicity, disease control and survival. Overall survival (OS) and Progression-free survival (PFS) were modeled using Cox proportional hazards models. Prognostic variables for OS-rate and PFS-rate were assessed using logistic regression model.

Results

200 patients were included. The median follow-up was 78 months. Grade 3 or greater esophagitis was 23%. The median OS for pooled population was 19.9 months (95% CI: 16.7-22.3), and 5-year OS rate was 20% (95% CI: 16-27%). The 2 year progression free survival was 26% (95% CI: 21-32%). Multivariate analysis found younger age p=0.02 (HR: 1.023, 95% CI: (1.00,1.04), and female sex p=0.02 (HR:0.69, 95% CI: 0.50-0.94) independently associated with improved overall survival.

Conclusion

2 Gy daily radiotherapy to a total dose of 70 Gy was well tolerated with similar survival to 45 Gy (1.5 Gy twice daily). This experience may aid practitioners decide whether high dose daily radiotherapy with platinum based chemotherapy is appropriate outside of a clinical trial.

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) represents approximately 15% of all lung cancers 1. Patients with limited stage small cell lung cancer (L-SCLC) are treated with curative intent, consisting of concurrent multiagent chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) followed by prophylactic cranial radiotherapy. The median survival for patients treated with combined modality therapy ranges from 18 to 23 months with 5-year survival between 15 and 26%.2-4

While radiotherapy improves survival for patients with L-SCLC 5, the ideal radiotherapy timing, dose, and fractionation is unknown. In an attempt to provide improved intrathoracic tumor control while not exceeding tolerance, a number of phase III studies have investigated concurrent chemotherapy and twice daily 3, 4, and split-course twice daily2 radiotherapy. Many consider the standard regimen to be 45 Gray (Gy) in 1.5 Gy twice-daily fractions delivered with concurrent and adjuvant cisplatin and etoposide because it was found to improve survival compared to 45 Gy in 1.8 Gy daily fractions.4 However, twice-daily fractionation has failed to gain widespread acceptance6. Many consider the control arm of INT 0096 inadequate, the esophagitis associated with twice daily radiotherapy too great, and twice daily radiotherapy logistically difficult.

A series of CALGB studies have investigated high-dose daily radiotherapy for L-SCLC as an alternative to twice daily radiotherapy. CALGB 8837, investigating the maximal tolerated dose of daily radiotherapy delivered with concurrent cisplatin/etoposide found 70 Gy radiotherapy delivered in 2 Gy daily fractions tolerable. 7 Subsequently, three studies 8-10 investigated concurrent carboplatin (AUC=5), etoposide (100 mg/m2) and 70 Gy radiotherapy for L-SCLC, following an initial two cycles of novel chemotherapy regimens. Although each CALGB study was relatively small, in combination these studies provide the largest prospective database of patients treated with high dose once daily radiotherapy and concurrent platinum based chemotherapy, for L-SCLC. Given that many practioners routinely choose a high dose regimen for their patients with L-SCLC, we pooled patients assigned to receive 70 Gy radiotherapy on these three consecutive prospective CALGB L-SCLC cancer trials and report their outcomes here.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility

Eligibility criteria for CALGB 39808, 30002, and 30206 have been previously published 8-10. Briefly, patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed L-SCLC, defined as disease confined to the ipsilateral hemithorax, nodal disease limited to the ipsilateral hilum and/or bilateral mediastinum, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0-1, and normal organ and marrow function were eligible. All patients included in this analysis started therapy with the intent to deliver two cycles of systemic therapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy to 70 Gy.

Chemotherapy treatment plan

The treatment plan for these studies consisted of two cycles of induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Induction chemotherapy on 39808 consisted of topotecan 1 mg/m2 days 1-5 and 22-26 and paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 day 1 and 22 with G-CSF 5 microg/kg day 6 and 27. CALGB 30002 included induction etoposide 160 mg/m2 PO d 5-7 and 26-28, paclitaxel 110 mg/ m2 d1 and 22, and topotecan 1.5 mg/ m2 d2-4 and 23-26, and 30206 included induction cisplatin 30 mg/ m2 and irinotecan 65 mg/ m2 both on d1,8,22,29. For all three trials, radiotherapy started on day 43 and was administered concurrently with carboplatin (area under the curve of 5 using the Calvert equation) on d 43, 64, 85 and etoposide 100 mg/ m2 d43-45,64-66, and 85-87. Details of premedication, dose modifications, and chemotherapy treatment delays have been published previously.

Radiation treatment plan

Following induction chemotherapy, all patients receiving radiation therapy underwent computed tomography (CT)-based radiation treatment planning. Gross tumor volumes of the primary (GTV-P) and pathologically involved lymph nodes (GTV-N) were contoured based on the post-chemotherapy volume. For the first phase of treatment, the primary tumor and pathologically involved adenopathy (those with a necrotic center, biopsy proven, PET avid, or measuring > 1 cm in short axis diameter) were contoured on each slice of the planning CT as gross tumor volume (GTV1). Clinical target volume 1 (CTV1) included GTV-P, GTV-N, the ipsilateral hilum, as well as lymph node stations 3, 4R, 4L, and 7. Stations 5 and 6 were included for left lung primary tumors. Planning target volume 1 (PTV-1) included CTV-1 with a 1 cm margin. Clinical target volume 2 included only GTV-P and GTV-N. Planning target volume 2 (PTV-2) included CTV-2 with a 1 cm margin.

Initially 2-dimensional as well as 3-dimensional conformal techniques were allowed. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy was not permitted. Radiation beam configurations were chosen to minimize dose to the heart and lungs. No corrections were made for tissue heterogeneity. The maximum dose to the spinal cord was limited to 50 Gy. Initially, 2 Gy daily fractions were delivered to PTV-1 to 44 Gy. Subsequently, an additional 26 Gy in 2 Gy fractions was delivered to PTV-2. The cumulative dose to gross disease was 70 Gy. Normal tissue guidelines included limiting 50% of the total lung volume < 25 Gy. The entire heart volume was to receive less than 25 Gy. Treatment was only delayed for grade 4 esophagitis or grade 4 neutropenia with fever. Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) was offered to patients with a complete response (CR) or a very good partial response (PR) as determined by restaging studies following the completion of all chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The dose of PCI was left to the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist with suggested schedules including 36 Gy (2 Gy/fraction), 25 Gy (2.5 Gy/fraction), and 24 Gy (3 Gy/fraction).

Follow-up and response measurement

Following the completion of treatment, patients were evaluated every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 3 years and subsequently at yearly intervals. At each evaluation, patients underwent history and physical examination, complete blood count, and chest radiography. Chest CT scans were performed every 6 months for 2 years and then yearly for 2 additional years.

Criteria for a complete response (CR) were the disappearance of all disease. A partial response (PR) was defined as > 50% reduction in the sum of the longest diameters of all measured target lesions without the development of new lesions or enlargement of any existing lesions. Stable disease was defined as a < 50% reduction or < 25% increase in the sum of the longest diameters of all measured target lesions compared with the size present at entry on study without the development of new lesions. Objective progression or relapse was defined as the appearance of new lesions or sites of disease or an increase in the sum of the longest diameters of all measured target lesions by >30% compared with the size referenced at study registration or at the time of maximum regression.

Statistical Analysis Method

CALGB statisticians performed all statistical analyses. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to describe overall survival and progression-free survival time and the relationship between the survival time and response. Survival time was defined as the time between the initiation of induction chemotherapy and death. Progression-free survival was computed as the time between initiation of induction chemotherapy and disease progression or death. Overall survival (OS) and Progression-free survival (PFS) are modeled using Cox proportional hazards models. Prognostic variables for OS-rate and PFS-rate were assessed using logistic regression model. Fisher’s exact tests, where appropriate, were performed for assessing statistical significance in frequency tables. All analyses were conducted on the entire study population regardless if they received the planned 70 Gy radiation therapy or not. The reported P-values are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple comparisons. P-values 0.05 were taken as being statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The first patient for 39808 was accrued in June 1999, for 30002 in October 2001, and for 30206 in January 2004. The study population comprised 63 patients from CALGB 30002, 75 patients from CALGB 30206, and 62 patients from 39808 for a total of 200 patients. Patient and tumor characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 62 years, most patients had minimal weight loss (76%), and most patients were male (51.5%). Characteristics were well balanced between the trials with the exception of improved performance status, less weight loss, and higher rates of baseline pleural effusion in 30206. The median follow-up was 78 months.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| 30002 (N = 63) | 30206 (N =75) | 39808 (N = 62) | Overall (N =200) | *p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.26 | |||||

| Male | 27 (43%) | 42(56%) | 34 (55%) | 103(52%) | ||

| Female | 36 (57%) | 33(44%) | 28 (45%) | 97(49%) | ||

| Age | 0.59 | |||||

| <60 | 25(40%) | 30(40%) | 29(47%) | 84(42%) | ||

| 60-70 | 28(44%) | 29(39%) | 26(42%) | 83(42%) | ||

| >70 | 10(16%) | 16(21%) | 7(11%) | 33(17%) | ||

| Median | 62 | 61 | 61.5 | 62 | ||

| Race | 0.19 | |||||

| White | 58(92%) | 73(97%) | 56(32%) | 187(94%) | ||

| Non-White | 5(8%) | 2(3%) | 6(10%) | 13(7%) | ||

| Performance Status | 0.0246 | |||||

| 0 | 27(43%) | 49(65%) | 30(48%) | 106(53%) | ||

| 1 | 33(52%) | 26(35%) | 29(47%) | 88(44%) | ||

| 2 | 3(5%) | 0(0%) | 3(5%) | 6(3%) | ||

| Weight loss | 0.03 | |||||

| None or <5% | 48(76%) | 65(87%) | 39(63%) | 152(76%) | ||

| 5-<10% | 10(16%) | 4(4%) | 13(21%) | 27(14%) | ||

| 10-<20% | 3(5%) | 4(5%) | 8(13%) | 15(7%) | ||

| >=20% | 2(3%) | 2(3%) | 2(2%) | 6(3%) | ||

| Pleural Effusion | 0.002 | |||||

| No | 62(98%) | 66(88%) | 62(100%) | 190(95%) | ||

| Yes | 1(2%) | 9(12%) | 0(0%) | 10(5%) |

Fisher’s exact test for balance among 3 studies

The mean and median radiation dose delivered to all patients was 68.9 Gy and 70 Gy, respectively. Radiation therapy was delivered per protocol in 93 patients (46.5%), 32 (16%) patients received radiation with a minor deviation and 32 (16%) had a major deviation. Five patients did not have radiation data available for review (2.5%).

Toxicity of induction Chemotherapy

The initial two cycles of chemotherapy were tolerated with the expected toxicities and responses. Toxicities are listed in Table 2. Hematologic adverse events predominated. Grade 3-4 neutropenia was the most common adverse event at 30%. Two grade 5 events were attributed to induction chemotherapy. The most common non-hematologic grade 3-4 AE was diarrhea (10%). Response to induction chemotherapy is shown in Table 3. The overall response rates were similar for all studies (CALGB 39808=77%, 30002=67%, 30206=71%, 72% for pooled population, p=0.86) as were the rates of stable disease and progression. Of the 200 patients who participated in these three trials, 179 (90%) proceeded to TRT following induction chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Adverse events during induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy

| Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Adverse Event | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Hemoglobin | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Leukocytes (total WBC) | 9 | (5%) | 8 | (4%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Lymphopenia | 5 | (3%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Neutrophils/granulocytes (ANC/AGC) | 23 | (12%) | 35 | (18%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Platelets | 7 | 4 | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Transfusion: pRBCs | 10 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Maximum Hematologic AE | 29 | 15% | 36 | 18% | 1 | (1%) |

| Fatigue | 9 | (5%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Anorexia | 6 | (3%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Dehydration | 6 | (3%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Diarrhea | 17 | (9%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Esophagitis | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Nausea | 9 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 12 | (6%) | 2 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Dyspnea | 10 | (5%) | 4 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Maximum Non-Hematologic AE | 46 | 24% | 6 | 3% | 1 | (1%) |

| Maximum Overall AE | 47 | 24% | 38 | 19% | 2 | 1% |

| Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 43 | (22%) | 5 | (3%) | 1 | (1%) |

| Leukocytes (total WBC) | 50 | (25%) | 45 | (23%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Lymphopenia | 19 | (10%) | 5 | (3%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Neutrophils/granulocytes (ANC/AGC) | 51 | (26%) | 108 | (54%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Platelets | 64 | (32%) | 21 | (11%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Transfusion: pRBCs | 21 | (11%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Maximum Hematologic AE | 47 | (24%) | 118 | (59%) | 1 | (1%) |

| Fatigue | 26 | (13%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Anorexia | 20 | (10%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Dehydration | 30 | (15%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Diarrhea | 20 | (10%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Esophagitis | 41 | (21%) | 4 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Nausea | 21 | (11%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 32 | (16%) | 5 | (3%) | 1 | (1%) |

| Dyspnea | 10 | (5%) | 4 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Maximum Non-Hematologic AE | 100 | (50%) | 21 | (11%) | 2 | (1%) |

| Maximum Overall AE | 57 | (29%) | 121 | (61%) | 3 | (2%) |

Table 3.

Response Rates Following Induction Chemotherapy and Chemoradiotherapy

| 30002 N=63 | 30206 N=75 | 39808 N=62 | Total N=200 | P-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction Chemotherapy | |||||

| CR | 5(8%) | 5(7%) | 1(2%) | 11(6%) | 0.63 |

| PR | 37(59%) | 48(64%) | 47(76%) | 132(66%) | |

| Stable | 13(21%) | 13(17%) | 12(19%) | 38(19%) | |

| PD | 1(2%) | 1(1%) | 1(2%) | 3(2%) | |

| Unevaluable | 7(11%) | 8(11%) | 1(2%) | 16(8%) | |

| Overall Response Rate | 42(67%) | 53(71%) | 48(77%) | 143(72%) | 0.86 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | |||||

| CR | 27(43%) | 28(37%) | 27(44%) | 82(41%) | 0.82 |

| PR | 25(40%) | 38(51%) | 30(48%) | 93(47%) | |

| Stable | 6(10%) | 6(8%) | 3(5%) | 15(8%) | |

| PD | 2(3%) | 1(1%) | 1(2%) | 4(2%) | |

| Unevaluable | 3(5%) | 2(3%) | 1(2%) | 6(3%) | |

| Overall Response Rate | 52(83%) | 66(88%) | 57(92%) | 175(88%) | 0.45 |

Fisher’s Exact test, excluding unevaluable patients

Toxicity of concurrent phase

Concurrent carboplatin, etoposide and TRT were tolerated with the expected side effects (Table 2). The most common grade 3-4 toxicities were hematologic. This included 80% grade 3-4 neutropenia, 48% grade 3-4 leukopenia, 43% grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia, and 25% grade 3-4 anemia. Nineteen percent experienced febrile neutropenia. The most common non-hematologic grade 3-4 toxicities were esophagitis, experienced by 23% of patients, and dehydration (15%).

Response to complete treatment package

Following the completion of induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy and TRT, the overall response rate was 88% similar to that of the individual studies (39808=92%, 30002=83%, 30206=88%, p=0.45) (Table 3).

Patterns of Progression

Patterns of first progression are reported in Table 4. Following the completion of therapy, 26 patients experienced locoregional progression only, 30 patients experienced locoregional progression and distant progression and 57 experienced distant progression only. The crude locoregional relapse rate at first progression was 28%.

Table 4.

Patterns of First Progression (online only)

| Relapse Type | 30002 | 30206 | 39808 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distant only | 18(29%) | 18(24%) | 21(34%) | 57(29%) |

| Local only | 8(13%) | 9(12%) | 9(15%) | 26(13%) |

| Local & Distant | 7(11%) | 14(19%) | 9(15%) | 30(15%) |

| No Relapse | 30(48%) | 34(45%) | 23(37%) | 87(44%) |

| Total | 63 | 75 | 62 | 200 |

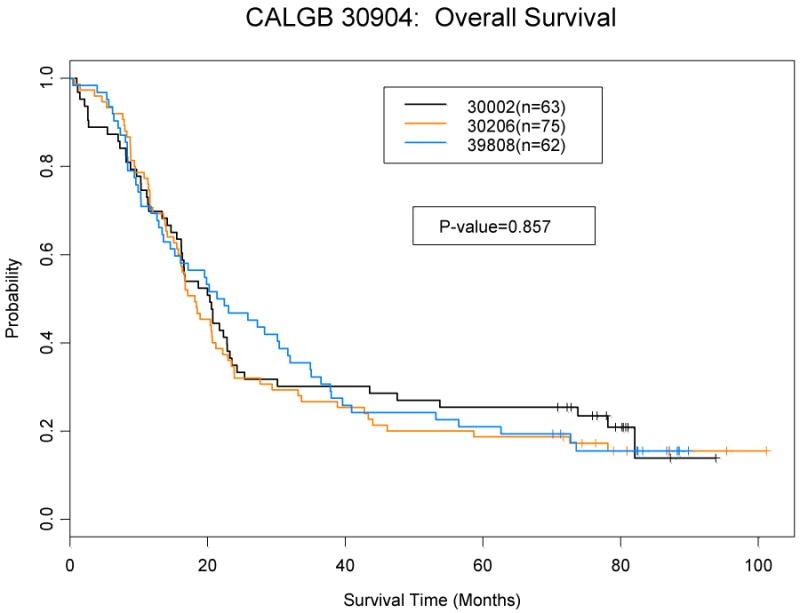

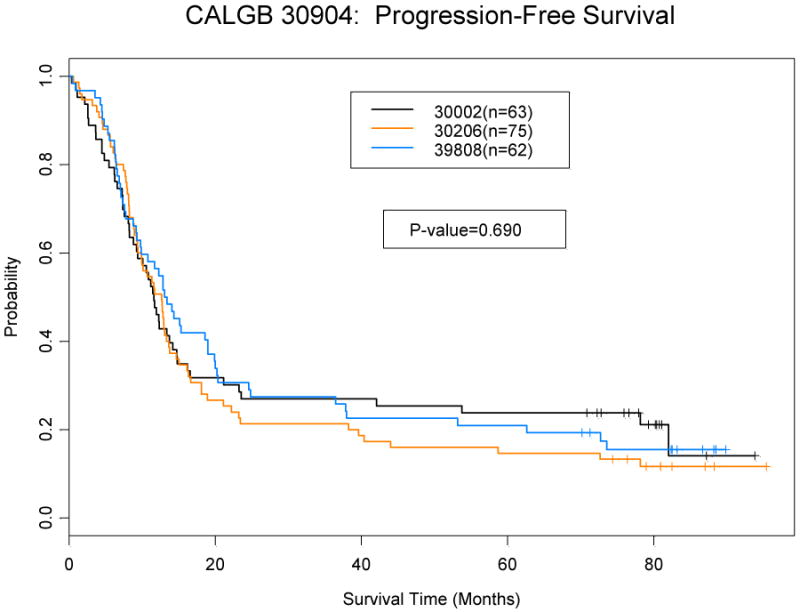

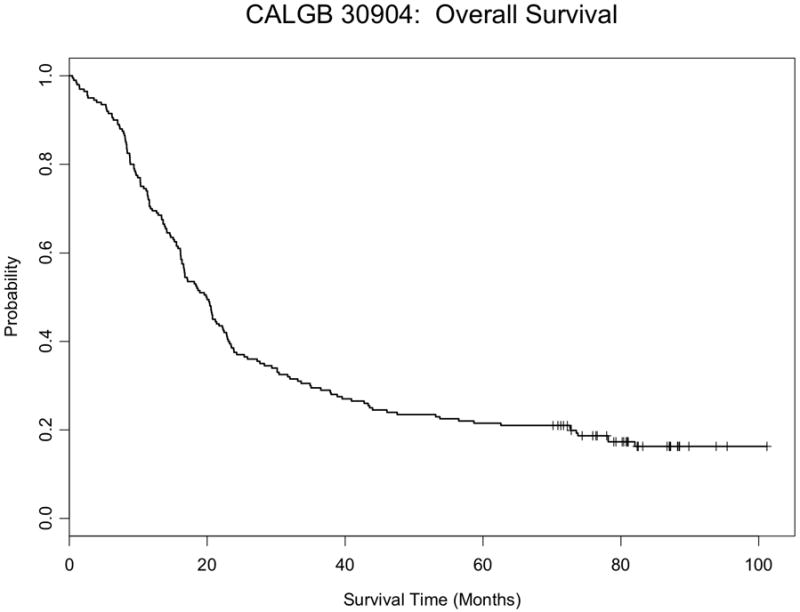

Survival

There was no difference in overall or progression free survival between studies (Figures 1). The median overall survival for pooled population was 19.9 months (95% CI: 16.7-22.3), which was similar to each trial individually (Table 5). The 2-year and 5-year overall survival rates were 37% (95% CI: 31-44%) and 21% (95% CI: 16-27%) respectively. The median and 2 year progression free survival was 12.3 months (95% CI: 10.8-13.6) and 26% (95% CI: 21-33%).

Figure 1.

a: Overall Survival by Study

b: Progression-free Survival by Study

c: Overall survival for all patients

d: Progression-free survival for all patients

Table 5.

Survival status by Study (n=200)

| 39808 (N=62) |

30002 (N=63) |

30206 (N=75) |

All 3 Studies (N=200) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Deaths | 52 | 50 | 63 | 165 |

| # of Progression | 52 | 50 | 66 | 168 |

| Median OS (mo) (95%CI) | 21.9 (15.2,32.0) | 20.3 (16.2, 23.5) | 18.1 (15.8, 22.9) | 19.9 (16.7, 22.3) |

| Median PFS (mo) (95%CI) | 13.2 (9.9,19.9) | 11.6 (9.3, 14.8) | 12.6 (9.4,14.7) | 12.3 (10.8, 13.6) |

| 2-Year OS | 45% (34%,59%) | 33% (24%,47%) | 31% (22%,43%) | 37% (31%,44%) |

| 2-PFS | 29% (20%,43%) | 25% (17%,39%) | 21% (14%,33%) | 26% (21%,32%) |

| 5-Year OS | 19% (12%,32%) | 23% (15%, 37%) | 17% (10%,28%) | 20% (16%,27%) |

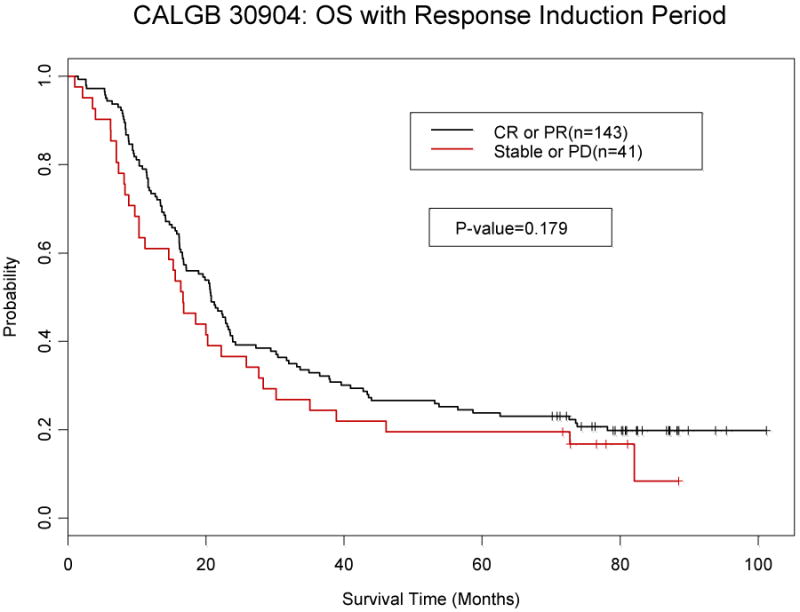

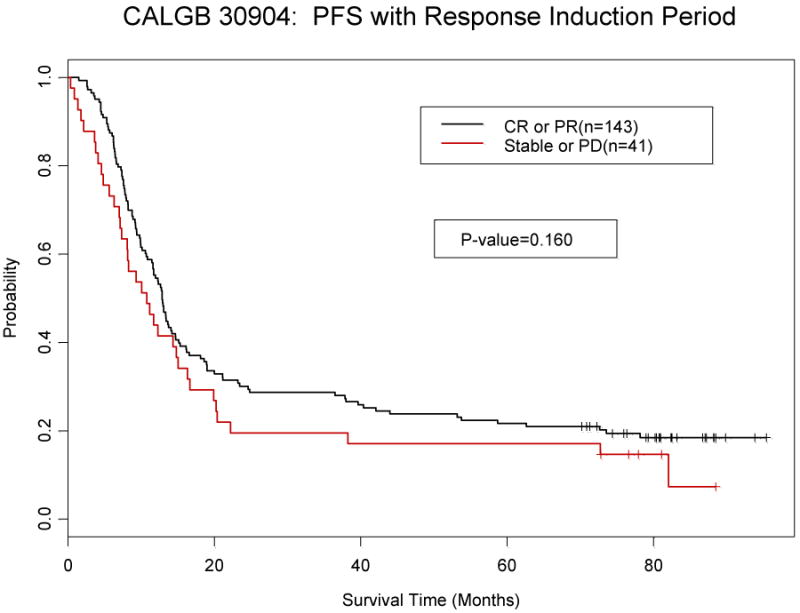

Patients with either a complete or partial response to induction chemotherapy were compared to those with stable disease or progression to determine if this would predict for overall or progression free survival. Responders had longer progression free (p=0.16) and overall survival (p=0.18), but it was not statistically significant. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

a: Overall Survival by response to induction chemotherapy

b: Progression-free survival by response to induction chemotherapy

Improved overall survival was associated with younger age (<60) (p=0.003) and female sex (p=0.02) in univariate analyses (Table 6). Multivariate analysis confirmed that younger age p=0.20 (HR: 1.02, 95% CI: (1.00,1.04), and female sex p=0.02 (HR:0.69, 95% CI: 0.50-0.94) were independently associated with improved overall survival when adjusted for performance status and weight loss (Table 7). Multivariate analysis for progression free survival identified a statistical trend for improved progression free survival in women (p=0.02) and in those with <5% weight loss (p=0.07) (data not shown). Age was not significantly associated with improved progression free survival.

Table 6.

Univariate Analyses (online only)

| Survival Distribution | 2-Year Overall Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No of Patients | Median (months) | Hazard Ratio | Wald p-value | Rate (%) | Wald p-value |

| Age, years | 200 | 1.027 | 0.0033 | 0.0181 | ||

| ≤ 59 | 84 | 21.0 | 44.1 | |||

| 60-70 | 83 | 17.1 | 37.4 | |||

| > 70 | 33 | 15.5 | 12.1 | |||

| Gender | 0.682 | 0.0167 | 0.0084 | |||

| Male | 103 | 16.7 | 28.2 | |||

| Female | 97 | 22.9 | 45.4 | |||

| Performance Status | 1.296 | 0.1023 | 0.1061 | |||

| 0 | 106 | 20.6 | 41.5 | |||

| 1& 2 | 94 | 17.0 | 30.9 | |||

| Weight Loss | 1.211 | 0.2961 | 0.1646 | |||

| <5% | 152 | 19.9 | 38.9 | |||

| ≥ 5% | 48 | 19.9 | 29.2 | |||

Median survivals are taken from Kaplan-Meier plots.

Hazard ratios are estimated from proportional hazards models.

P values are from proportional hazards model using the Wald test.

Two-year survival rates are taken from Kaplan-Meier plots.

P values are from logistic regression analysis.

Table 7.

Multivariate analysis (online only)

| Overall Survival | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | P-value | Hazard Ratio 95% CI |

| Age | 0.0165 | 1.023 (1.004, 1.042) |

| Gender | 0.0192 | 0.685 (0.499, 0.940) |

| Performance Status | 0.2004 | 1.231 (0.896, 1.692) |

| Weight Loss | 0.6893 | 1.078 (0.746, 1.556) |

| Progression-free Survival | ||

| P-value | Hazard Ratio 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.1509 | 1.013 (0.995,1.032) |

| Gender | 0.0217 | 0.693 (0.507, 0.948) |

| Performance Status | 0.3998 | 1.145 (0.835, 1.569) |

| Weight Loss | 0.0731 | 1.394 (0.969,2.004) |

Discussion

In this analysis we report the outcomes of 200 consecutive patients treated on three CALGB protocols who received two cycles of induction therapy followed by 70 Gy daily radiotherapy administered concurrently with platinum based chemotherapy for LS SCLC, followed by PCI in responding patients. These patients treated with high dose daily radiotherapy had rates of grade 3 or greater (3+) esophagitis of 23%, median survival of 19.9 months and 5-year survival of 21%. The survival was similar to those reported for patients on the two phase III trials with twice daily radiotherapy. On INT 0096 patients had 32% grade 3+ esophagitis, 23 month median survival, and 26% 5-year survival. In NCCTG 89-20-52 patients had a 12% rate of 3+ esophagitis, 20.6-month median survival, and a 22% 5-year survival2, 4 However, the esophagitis rates appeared lessened with daily fractionation or split course twice-daily fractionation.

Data on large numbers of L-SCLC patients treated with daily radiotherapy to high doses are scarce and limited to single institution series. While select retrospective reports 11-13 have supported the use of high dose radiotherapy, the data presented here represent the largest series to date using this approach. Patients in this series were treated with a standardized approach at multiple institutions on prospective phase II studies with central data monitoring and collection, as well as central radiotherapy QA. Therefore, the resulting data more accurately describe the results of concurrent chemotherapy and high-dose daily radiotherapy. The limitations of this study are that all patients were treated with two cycles of chemotherapy prior to chemo-radiotherapy. Some patients progressed during induction therapy and, thus, did not receive the potential benefits of radiotherapy. Furthermore, there are limitations in comparing the results of phase II and phase III trials, particularly when the studies are conducted in different eras with the potential to select somewhat different patient populations.

Although accelerated radiotherapy delivered in twice daily 1.5 Gy fractions to a total dose of 45 Gy was shown to improve survival compared to 45 Gy radiotherapy delivered in 1.8 Gy daily fractions, this has not been widely adopted. The reasons for the lack of widespread adoption are likely related to the logistical difficulties of delivering twice-daily therapy as well as the 32% grade 3-4 esophagitis rate. Based on extrapolation from phase I data 7 as well as radiation dose response data 14, many have delivered radiotherapy in daily fractionated radiotherapy to doses > 50 Gy 11, 12. However, these single institution series are hindered by their retrospective nature and small size.

In our pooled analysis we found that 2 Gy daily radiotherapy to a total dose of 70 Gy was relatively well tolerated. Grade 3-4 esophagitis was 23% compared to 32% Grade 3-4 esophagitis rate seen in INT-0096. Both of these studies used similar radiation techniques without intentional sparing of the esophagus. However, RTOG 0239 reported a low grade 3 or higher esophagitis rate (18%) delivering radiation therapy via an accelerated concomitant boost technique15. However, as this study was conducted in an era of more advanced radiation planning techniques with guidelines limiting the amount of esophagus that could receive high doses of radiation therapy. With further advanced radiotherapy planning techniques and potentially the use of limited radiation fields, the rates of esophagitis for all treatment delivery schemes should be further reduced. We also found that rates of grade 3-5 pulmonary toxicity was low, and will present these results and predictors of toxicity in another paper.

The favorable survival, and locoregional control in this series was obtained even though a carboplatin-based regimen was given during radiotherapy and the initiation of radiotherapy was delayed until the 3rd cycle of chemotherapy. The substitution of carboplatin for cisplatin and etoposide in SCLC remains controversial, and carboplatin was adopted in the CALGB phase II studies given the preference of many participating community oncologists to use the drug. That said cisplatin remains the standard of care outside of a clinical trial, particularly when treating potentially curable patients with limited stage disease. The optimal timing of initiating radiotherapy likewise remains an area of controversy. 3, 16 Randomized studies and meta-analyses 17, 18 have shown a benefit for earlier radiotherapy. It is possible based on these studies that the results of the present study would have been more favorable if the radiotherapy component was started earlier than with cycle 3 of chemotherapy.

Locoregional control in this series was 77%, which compared favorably to the 64% seen in INT-0096, and similar to that seen in RTOG 0239. Dose response data of daily fractionated chemoradiotherapy demonstrate a dose response relationship suggesting that doses > 50 Gy are associated with improved locoregional control 14, 19, 20. An unanswered question is whether even higher doses of radiotherapy would be associated with improved locoregional control. We selected 70 Gy as it was the highest dose investigated in the underlying phase I study 7. However, maximum tolerated dose was not reached in that study. Others have reported21 on the potential relationship between biologically effective dose (BED) of RT and 5-year survival suggesting potential benefits for the higher dose regimens used in CALGB 30610. Whether even higher doses can be improve the therapeutic ratio, particularly in an era of advanced imaging and treatment delivery, is fertile ground for future research.

Whether 70 Gy daily radiotherapy is better than the current standard of care is an open question which is currently addressed in an ongoing intergroup study (CALGB 30610). A separate phase III trial in the United Kingdom and Canada is comparing 66 Gy daily radiotherapy with 45 Gy twice-daily radiotherapy. Until those trials are completed and their data are mature, the CALGB phase II experience can help practitioners decide whether the high dose daily radiotherapy delivered concurrently with platinum based chemotherapy is appropriate outside of a clinical trial for patients with L-SCLC.

References

- 1.Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4539–4544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schild SE, Bonner JA, Shanahan TG, et al. Long-term results of a phase III trial comparing once-daily radiotherapy with twice-daily radiotherapy in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2004;59:943–951. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Acimovic L, et al. Initial versus delayed accelerated hyperfractionated radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer: a randomized study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:893–900. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turrisi AT, 3rd, Kim K, Blum R, et al. Twice-daily compared with once-daily thoracic radiotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer treated concurrently with cisplatin and etoposide. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;340:265–271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901283400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1618–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Movsas B, Moughan J, Komaki R, et al. Radiotherapy patterns of care study in lung carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:4553–4559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi NC, Herndon JE, 2nd, Rosenman J, et al. Phase I study to determine the maximum-tolerated dose of radiation in standard daily and hyperfractionated-accelerated twice-daily radiation schedules with concurrent chemotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:3528–3536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogart JA, Herndon JE, 2nd, Lyss AP, et al. 70 Gy thoracic radiotherapy is feasible concurrent with chemotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: analysis of Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 39808. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2004;59:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller AA, Wang XF, Bogart JA, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel-topotecan-etoposide followed by consolidation chemoradiotherapy for limited-stage small cell lung cancer: CALGB 30002. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2007;2:645–651. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318074bbf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley M, Bogart J, Hodgeson L, et al. CALGB 30206: Phase II study of induction cisplatin (P) and irinotecan (I) followed by combination carboplatin (C), etoposide (E), and thoracic radiotherapy for limited stage small cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:7565. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827628e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller KL, Marks LB, Sibley GS, et al. Routine use of approximately 60 Gy once-daily thoracic irradiation for patients with limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2003;56:355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04493-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papac RJ, Son Y, Bien R, et al. Improved local control of thoracic disease in small cell lung cancer with higher dose thoracic irradiation and cyclic chemotherapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1987;13:993–998. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins JM, Fortney JA, Wahlquist AE, et al. Once-daily radiotherapy to > or =59.4 Gy versus twice-daily radiotherapy to > or =45.0 Gy with concurrent chemotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: a comparative analysis of toxicities and outcomes. Japanese journal of radiology. 2010;28:340–348. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi NC, Carey RW. Importance of radiation dose in achieving improved loco-regional tumor control in limited stage small-cell lung carcinoma: an update. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1989;17:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komaki R, Paulus R, Ettinger D, et al. A phase II study of accelerated high-dose thoracic radiation therapy (AHTRT) with concurrent chemotherapy for limited small cell lung cancer: RTOG 0239. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl) abstr 7527. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray N, Coy P, Pater JL, et al. Importance of timing for thoracic irradiation in the combined modality treatment of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:336–344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Ruysscher D, Pijls-Johannesma M, Bentzen SM, et al. Time between the first day of chemotherapy and the last day of chest radiation is the most important predictor of survival in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:1057–1063. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried DB, Morris DE, Poole C, et al. Systematic review evaluating the timing of thoracic radiation therapy in combined modality therapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:4837–4845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roof KS, Fidias P, Lynch TJ, et al. Radiation dose escalation in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2003;57:701–708. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coy P, Hodson I, Payne DG, et al. The effect of dose of thoracic irradiation on recurrence in patients with limited stage small cell lung cancer. Initial results of a Canadian Multicenter Randomized Trial. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1988;14:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schild SE, Bonner JA, Hillman S, et al. Results of a phase II study of high-dose thoracic radiation therapy with concurrent cisplatin and etoposide in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer (NCCTG 95-20-53) Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:3124–3129. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]