Abstract

Human mitochondrial protein mitoNEET is a novel target of type II diabetes drug pioglitazone, and contains a redox active [2Fe–2S] cluster that is hosted by a unique ligand arrangement of three cysteine and one histidine residues. Here we report that zinc ion can compete for the [2Fe–2S] cluster binding site in human mitoNEET and potentially modulate the physiological function of mitoNEET. When recombinant mitoNEET is expressed in Escherichia coli cells grown in M9 minimal media, purified mitoNEET contains very little or no iron–sulfur clusters. Addition of exogenous iron or zinc ion in the media produces mitoNEET bound with a [2Fe–2S] cluster or zinc, respectively. Mutations of the amino acid residues that hosting the [2Fe–2S] cluster in mitoNEET diminish the zinc binding activity, indicating that zinc ion and the [2Fe–2S] cluster may share the same binding site in mitoNEET. Finally, excess zinc ion effectively inhibits the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET in E. coli cells, suggesting that zinc ion may impede the function of mitoNEET by blocking the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in the protein.

Keywords: Human mitoNEET, Type II diabetes drug pioglitazone, Iron–sulfur cluster, Zinc binding

Introduction

Human mitochondrial protein mitoNEET is a novel target of type II diabetes drug pioglitazone (Colca et al. 2004). The protein is localized on mitochondrial outer membrane (Wiley et al. 2007a) and belongs to a small protein family that contains a conserved CDGSH domain (Lin et al. 2011). In addition to pioglitazone, mitoNEET also binds natural compounds NADPH (Zhou et al. 2010) and resveratrol-3-sulfate (Arif et al. 2011), although their physiological significance remains elusive. Expression of soluble C-terminal mitoNEET (residue 33–108) in Escherichia coli cells grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) media produced a protein that contains a [2Fe–2S] cluster (Wiley et al. 2007b). Crystallographic studies revealed that mitoNEET forms a homodimer with each monomer hosting a [2Fe–2S] cluster via three cysteine (Cys-72 and Cys-74 and Cys-83) and one histidine (His-87) residues (Hou et al. 2007; Lin et al. 2007; Paddock et al. 2007). The [2Fe–2S] cluster in mitoNEET is redox active (Tirrell et al. 2009) with a midpoint redox potential of ~0 mV (pH 6.0) (Bak et al. 2009). The redox property of the [2Fe–2S] cluster in mitoNEET can be further modulated by pH (Tirrell et al. 2009), NADP+/NADPH (Zhou et al. 2010; Zuris et al. 2012), the diabetes drug pioglitazone (Bak et al. 2009), and the inter-domain communication within mitoNEET (Baxter et al. 2011). Deletion of mitoNEET in mice resulted in a reduced oxidative phosphorylation capacity in mitochondria (Wiley et al. 2007a), suggesting that mitoNEET has a crucial role for energy metabolism. While the physiological function of mitoNEET has not been fully established, it has recently been postulated that mitoNEET may be involved in iron– sulfur cluster biogenesis by transferring the assembled clusters to target proteins (Zuris et al. 2011, 2012).

The conserved CDGSH domain which is part of the [2Fe–2S] cluster binding site in mitoNEET (Hou et al. 2007; Lin et al. 2007; Paddock et al. 2007) was initially annotated as a zinc-finger motif (Wiley et al. 2007a), although the potential zinc binding activity of mitoNEET was not investigated. Zinc is the second most abundant transition metal in the human body, and has an important role in facilitating the correct folding of proteins, stabilizing the domain structure, and providing catalytic functions in various enzymes (Beyersmann and Haase 2001). On the other hand, excess zinc in cells has been linked to several human diseases (Koh et al. 1996; Cuajungco and Lees 1997; Duce et al. 2010). Whereas the molecular mechanism for zinc-mediated cytotoxicity has not been fully understood, increasing evidence indicated that excess zinc can disrupt energy metabolism and ATP production in mitochondria (Sharpley and Hirst 2006; Lemire et al. 2008). Since zinc and iron–sulfur cluster share the same binding site in proteins such as the iron– sulfur cluster assembly protein IscU (Ramelot et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2005) and in the CysB motif of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase C-terminal domain (Klinge et al. 2009; Netz et al. 2012), mis-incorporation of zinc ion into the iron–sulfur cluster binding sites could result in dysfunctional protein and contribute to the metal-mediated cytotoxicity (Pagani et al. 2007). Here, we report that human mitoNEET is able to bind zinc ion likely within the [2Fe–2S] cluster binding site, and that excess zinc can effectively block the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET in E. coli cells. The results suggest that zinc ion may impede the energy metabolism in mitochondria by disrupting the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET.

Materials and methods

Protein purification

The cDNA encoding human mitoNEET33–108 was cloned from cDNA library. The PCR product was digested with restriction enzymes NcoI and HindIII and ligated to an expression vector pET28b+ (Novagen Co). The cloned DNA fragment was confirmed by direct sequencing, and recombinant mitoNEET was expressed in E. coli BL21 strain grown in either rich LB media or M9 minimal media supplemented with glycerol (0.2 %), thiamin (5 µg ml−1) and 20 amino acids (each at 10 µg ml−1). After 4 h of incubation at 37 °C with aeration (250 rpm), ferric citrate or ZnSO4 was added 10 min before the protein expression was induced with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (200 µM) under aerobic conditions. The cells were then grown at room temperature with aeration (150 rpm) overnight before being harvested. The mitoNEET mutants in which cysteine residues were substituted with serine were constructed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene Co.). The growth media and all chemicals were prepared with double-distilled de-ionized water. Proteins were purified following the procedures described in Yang et al. (2006), and purity of purified protein was over 95 %, judging from the SDS/PAGE followed by the Coomassie blue staining. The protein concentration of purified mitoNEET was measured at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 8.6 cm−1 mM−1.

Iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU

Escherichia coli apo-IscU was purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media without any addition of exogenous metal ions as described previously (Wang et al. 2010). For the iron–sulfur cluster assembly reaction, purified apo-IscU was incubated with cysteine desulfurase IscS (0.5 µM), NaCl (200 mM), Tris (20 mM, pH 8.0), and Fe(NH4)2 (SO4)2 (100 µM) in the presence of dithiothreitol (2 mM) under anaerobic conditions (Yang et al. 2006). l-Cysteine (1 mM) was then added to initiate the iron– sulfur cluster assembly in IscU. The iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU was monitored in a Beckman DU-640 UV–visible spectrometer equipped with a temperature controller.

EPR measurements

The X-band EPR (Electron paramagnetic resonance) spectra were recorded using a Bruker model ESR-300 spectrometer equipped with an Oxford Instruments 910 continuous flow cryostat. Routine EPR conditions were: microwave frequency, 9.47 GHz; microwave power, 10.0 mW; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 1.2 mT; temperature, 25 K; receive gain, 105.

Metal content analyses

The iron content in protein samples was determined using an iron indicator ferroZine following the procedures described in (Cowart et al. 1993). The zinc contents in protein samples were determined using a zinc indicator PAR (4-(2-pyridylazo)-resorcinol) (Bae et al. 2004). The zinc and iron contents in protein samples were also analyzed by the Inductively Coupled Plasma-Emission Spectrometry (ICP-ES). Both methods provided similar results.

Results

Human mitoNEET binds zinc in E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media

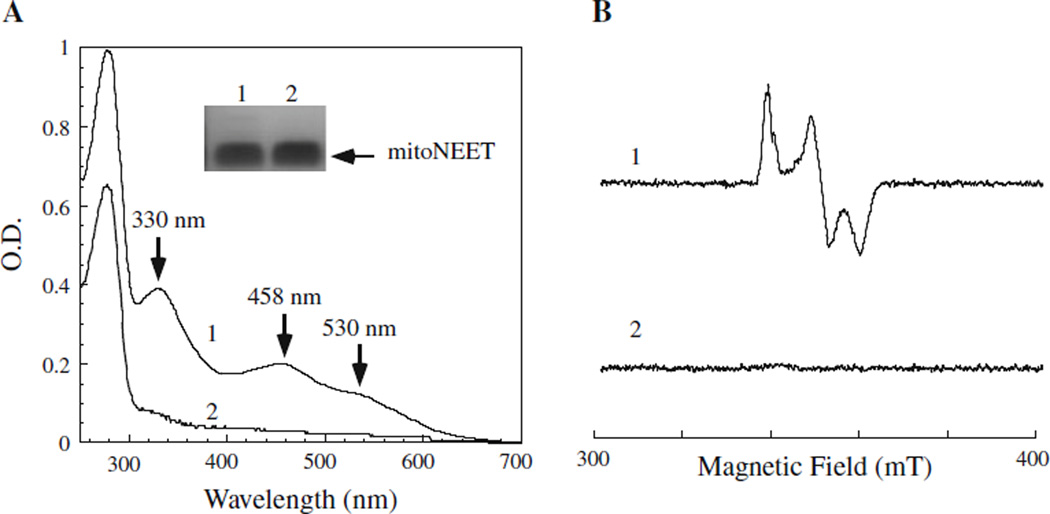

When recombinant human mitoNEET was expressed in E. coli cells grown in LB media, purified protein had absorption peaks at 330, 458 and 530 nm, indicative of a [2Fe–2S] cluster, as reported previously (Wiley et al. 2007b). However, when recombinant mitoNEET was expressed in E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media, purified mitoNEET had very little or no absorption of iron–sulfur clusters (Fig. 1a). The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements confirmed that while mitoNEET purified fromE. coli cells grown in LB media contained a [2Fe–2S] cluster, mitoNEET purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media had no detectable amounts of iron–sulfur clusters (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Metal occupancy of human mitoNEET expressed in E. coli cells depends on growth media. Human mitoNEET was expressed in E. coli cells grown in LB media or M9 minimal media under aerobic conditions. a UV–visible absorption spectra of purified mitoNEET. Purified mitoNEET (75 µM) was dissolved in buffer containing Tris (20 mM, pH 8.0) and NaCl (200 mM). Insert is a photograph of SDS-PAGE gel of purified mitoNEET from E. coli cells grown in LB (lane 1) or M9 minimal media (lane 2). b EPR spectra of purified mitoNEET. MitoNEET (200 µM) purified from E. coli cells grown in LB (spectrum 1) or M9 minimal media (spectrum 2) were dissolved in buffer containing Tris (20 mM, pH 8.0) and NaCl (200 mM). Protein was reduced with freshly prepared sodium dithionite (1 mM) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until the EPR measurements

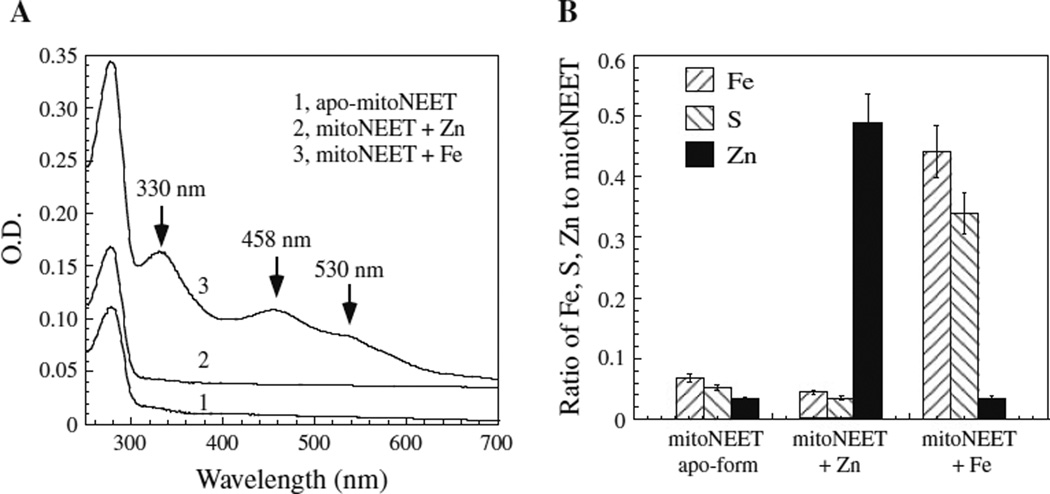

When the M9 minimal media were supplemented with exogenous iron before expression of mitoNEET was induced in E. coli cells, purified mitoNEET had absorption peaks at 330, 458 and 530 nm of the [2Fe–2S] cluster (Fig. 2a), indicating that supplement of exogenous iron can restore the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET in cells. In parallel, when the M9 minimal media were supplemented with exogenous zinc before expression of mitoNEET was induced in E. coli cells, purified mitoNEET had no absorption peaks of iron– sulfur clusters (Fig. 2a). However, the metal content analyses showed that mitoNEET purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with zinc contained about 0.49 ± 0.05 zinc atom per protein monomer (Fig. 2b) (n = 3), suggesting that human mitoNEET is able to bind zinc in E. coli cells.

Fig. 2.

Human mitoNEET binds zinc or a [2Fe–2S] cluster in E. coli cells. a UV–visible absorption spectra of mitoNEET purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with no exogenous metal ions (spectrum 1), ZnSO4 (20 µM) (spectrum 2), or ferric citrate (5 µM) (spectrum 3). b iron, sulfide and zinc contents of mitoNEET purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with no exogenous metal ions (mitoNEET-apo-form), ZnSO4 (20 µM) (mitoNEET-Zn), or ferric citrate (5 µM) (mitoNEET-Fe). The iron, sulfide and zinc contents were presented as the ratio to mitoNEET monomer. The data are averages plus standard deviations from three independent experiments

Zinc and the [2Fe–2S] cluster likely share the binding site in mitoNEET

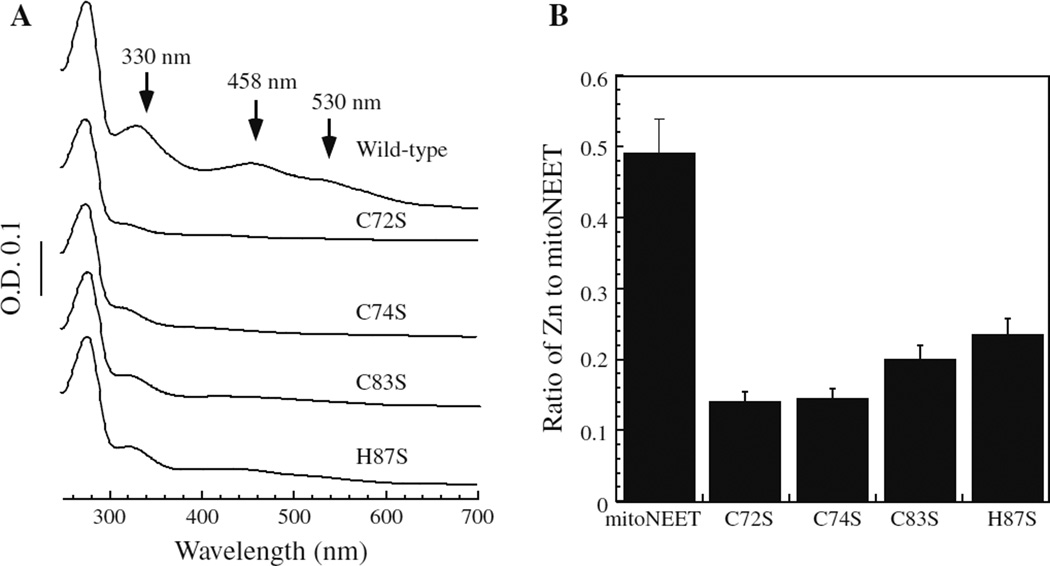

The putative zinc-finger motif CDGSH in mitoNEET contains two amino acid residues (Cys-83 and His-87) that are the ligands for the [2Fe–2S] cluster (Hou et al. 2007; Lin et al. 2007; Paddock et al. 2007). To test whether the amino acid residues that host the [2Fe–2S] cluster in mitoNEET are involved in zinc binding, we constructed mitoNEET mutants in which each of the residues (Cys-72, Cys-74, Cys-83, and His-87) was replaced with serine. When the mitoNEET mutant proteins were expressed in E. coli cells grown in the M9 minimal media supplemented with ferric citrate, none of the mutant proteins were able to assemble an intact [2Fe–2S] cluster (Fig. 3a). In parallel, when the mitoNEET mutant proteins were expressed in E. coli cells grown in the M9 minimal media supplemented with ZnSO4, purified mitoNEET mutant proteins contained less than half of total zinc bound in wild type mitoNEET (Fig. 3b). These results suggested that zinc and [2Fe–2S] cluster likely share the same binding site in mitoNEET.

Fig. 3.

Zinc and [2Fe–2S] cluster share the same binding site in mitoNEET. The mitoNEET mutants (C72S, C74S, C83S and H87S) were expressed and purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with ferric citrate or ZnSO4. a UV–visible absorption spectra of mitoNEET mutant proteins purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with ferric citrate (5 µM). b The zinc content of mitoNEET mutant proteins purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with ZnSO4 (20 µM). The ratio of zinc per mitoNEET monomer was plotted for wild type and each mutant protein samples. The data are averages plus standard deviations from at least three independent experiments

Zinc competes for the [2Fe–2S] cluster binding site in mitoNEET in E. coli cells

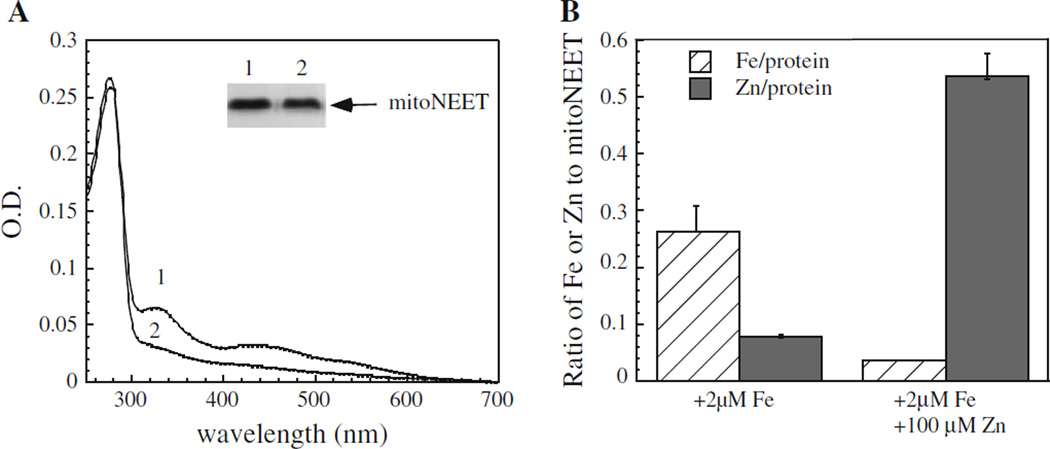

If mitoNEET can bind zinc and [2Fe–2S] cluster in the same binding site, we would anticipate that excess zinc ion may compete for the [2Fe–2S] cluster binding in mitoNEET. To test this idea, mitoNEET was expressed in E. coli cells grown in the M9 minimal media supplemented with various amounts of zinc and iron ions. Figure 4a shows an example of competition between zinc and iron–sulfur cluster binding in mitoNEET in E. coli cells. When M9 minimal media were supplemented with ferric citrate, purified mitoNEET contained a [2Fe–2S] cluster as expected (Fig. 4a). Addition of excess zinc ion (100 µM) to the above M9 minimal media essentially eliminated the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET (Fig. 4a) with concomitant increase of zinc content in the protein (Fig. 4b). Thus, excess zinc ion can effectively block the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET in E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media.

Fig. 4.

Zinc competes for the [2Fe–2S] cluster binding site in mitoNEET in E. coli cells. a UV–visible absorption spectra of mitoNEET purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with ferric citrate (2.0 µM) (spectrum 1), ferric citrate (2.0 µM) and ZnSO4 (100 µM) (spectrum 2). The insert is a photograph of SDS/PAGE gel of purified proteins. b Zinc and iron contents of mitoNEET purified from E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with ferric citrate (2.0 µM), or with ferric citrate (2.0 µM) and ZnSO4 (100 µM). The data are representatives of three independent experiments

Zinc inhibits the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU

Iron–sulfur clusters are assembled by a group of dedicated proteins that are highly conserved from bacteria to humans (Zheng et al. 1998; Lill 2009). Among them, IscU acts as a key scaffold protein that assembles transient iron–sulfur clusters (Agar et al. 2000) and transfers the clusters to target proteins (Raulfs et al. 2008). Interestingly, IscU, like mitoNEET, has been shown to bind zinc in the iron–sulfur cluster binding site (Ramelot et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2005). Thus, zinc ion may block the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in mitoNEET by inhibiting the initial iron– sulfur cluster formation in IscU in cells.

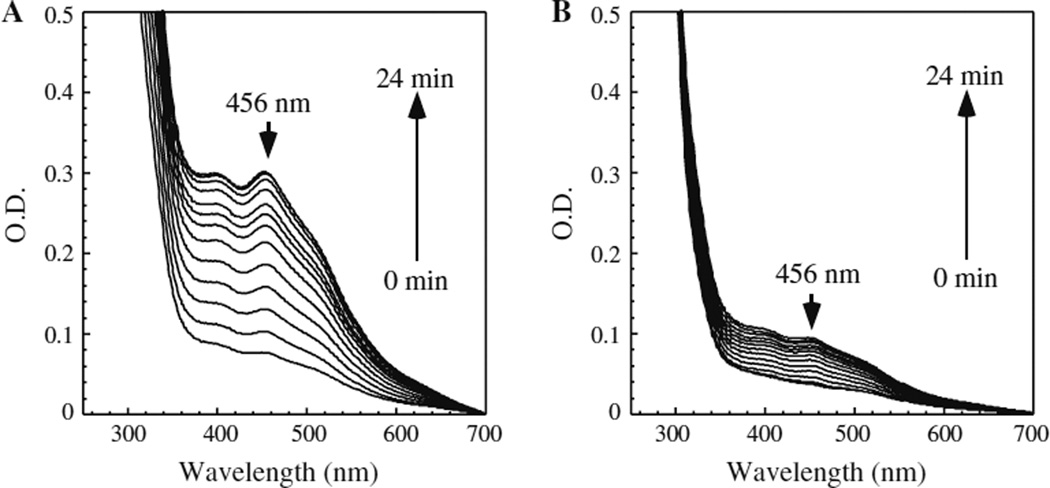

To test this idea, apo-form IscU was incubated with ferrous iron, l-cysteine, and cysteine desulfurase IscS, in the presence of dithiothreitol under anaerobic conditions as described previously (Yang et al. 2006). Figure 5a shows the typical iron–sulfur cluster assembly process in IscU under the experimental conditions. The absorption peak at 456 nm reflecting the [2Fe–2S] cluster formation in IscU (Agar et al. 2000) quickly appeared upon addition of l-cysteine and reached the maximum within 20 min. In contrast, when an equivalent amount of zinc ion (relative to the iron concentration) was included in the incubation solution, the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU was greatly inhibited (Fig. 5b). As a control, addition of an equal amount of MgSO4 had no effect on the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU under the same experimental conditions (data not shown), suggesting that zinc ion has its specific effect on the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in protein.

Fig. 5.

Zinc inhibits the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU in vitro. a Iron–sulfur cluster assembly in IscU. Purified IscU (150 µM) was incubated with Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 (100 µM), IscS (0.5 µM) and DTT (2 mM) under anaerobic conditions. l-cysteine (1 mM) was added after 5 min pre-incubation at 37 °C. The UV–visible absorption spectrum was taken every 2 min for 24 min. b Same as (a) except 100 µM ZnSO4 was included in the incubation solution

Discussion

Here we report that human outer mitochondrial membrane protein mitoNEET is able to bind not only a [2Fe–2S] cluster but also zinc ion in E. coli cells. While recombinant human mitoNEET expressed in E. coli cells grown in M9 minimal media contains very little or no iron–sulfur clusters, addition of exogenous iron or zinc ion in M9 minimal media produces mitoNEET bound with a [2Fe–2S] cluster or zinc, respectively. MitoNEET mutants that fail to bind the [2Fe–2S] cluster also have a diminished binding activity for zinc, indicating that zinc and iron–sulfur cluster may share the same binding site in mitoNEET. Finally, excess zinc can effectively inhibit the [2Fe– 2S] cluster assembly in mitoNEET in E. coli cells. Taken together, the results suggest that zinc may disrupt the physiological function of mitoNEET by blocking the [2Fe–2S] cluster assembly in the protein.

It has previously been reported that zinc and iron– sulfur cluster share the same binding site in some proteins including the iron–sulfur cluster assembly protein IscU (Ramelot et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2005) and the eukaryotic DNA polymerases (Klinge et al. 2009; Netz et al. 2012). Here we find that human mitochondrial protein mitoNEET can also bind zinc likely within the iron–sulfur cluster binding site. Conceivably, there are other proteins with such a flexible binding site to accommodate iron–sulfur cluster or zinc binding. It should be emphasized that binding of iron–sulfur cluster or zinc ion in these proteins will depend on intracellular concentrations of iron and zinc. In this context, at low concentrations, zinc may regulate the activity of iron–sulfur proteins by competing for the iron–sulfur cluster binding site. At high concentrations, zinc may become highly toxic by completely blocking the iron–sulfur cluster assembly in proteins (Pagani et al. 2007).

While the physiological function of mitoNEET has not been fully established, it has recently been postulated that mitoNEET may act as a carrier for iron–sulfur cluster assembly in human cells (Zuris et al. 2011, 2012). Iron–sulfur clusters are involved in diverse cellular functions, and assembly of iron–sulfur clusters requires a group of dedicated proteins that are highly conserved from bacteria to humans (Zheng et al. 1998; Lill 2009). In bacteria, iron–sulfur clusters are initially assembled in a scaffold protein IscU (Agar et al. 2000) and transferred to target proteins (Raulfs et al. 2008). In eukaryotic cells, mitochondria are the primary sites for initial iron–sulfur cluster assembly (Lill 2009). For iron–sulfur assembly in cytosol and nucleus, the iron– sulfur clusters assembled in mitochondria may be transferred across mitochondrial membranes (Lill 2009). MitoNEET, a mitochondrial outer membrane protein, could be one of the missing components for transporting the assembled iron–sulfur clusters from mitochondria to cytosol. Since deficiency of iron– sulfur clusters has been attributed to a number of human diseases (Rouault and Tong 2008; Lill 2009), and mitoNEET has an important role in energy metabolism (Wiley et al. 2007a), we propose that excessive zinc may disrupt cellular functions by impeding iron–sulfur cluster assembly in proteins such as mitoNEET in human cells.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01CA107494, and by the Chinese Natural Science Foundation grants (31228006 and 31200587).

Contributor Information

Guoqiang Tan, Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China.

Aaron P. Landry, Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, 202 Life Sciences Building, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA

Ruili Dai, Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China.

Li Wang, Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China.

Jianxin Lu, Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China.

Huangen Ding, Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, 202 Life Sciences Building, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA, hding@lsu.edu.

References

- Agar JN, Krebs C, Frazzon J, Huynh BH, Dean DR, Johnson MK. IscU as a scaffold for iron–sulfur cluster biosynthesis: sequential assembly of [2Fe–2S] and [4Fe–4S] clusters in IscU. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7856–7862. doi: 10.1021/bi000931n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif W, Xu S, Isailovic D, Geldenhuys WJ, Carroll RT, Funk MO. Complexes of the outer mitochondrial membrane protein mitoNEET with resveratrol-3-sulfate. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5806–5811. doi: 10.1021/bi200546s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JB, Park JH, Hahn MY, Kim MS, Roe JH. Redox-dependent changes in RsrA, an anti-sigma factor in Streptomyces coelicolor: zinc release and disulfide bond formation. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak DW, Zuris JA, Paddock ML, Jennings PA, Elliott SJ. Redox characterization of the FeS protein mitoNEET and impact of thiazolidinedione drug binding. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10193–10195. doi: 10.1021/bi9016445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter EL, Jennings PA, Onuchic JN. Interdomain communication revealed in the diabetes drug target mitoNEET. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5266–5271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017604108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyersmann D, Haase H. Functions of zinc in signaling, proliferation and differentiation of mammalian cells. Biometals. 2001;14:331–341. doi: 10.1023/a:1012905406548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colca JR, McDonald WG, Waldon DJ, Leone JW, Lull JM, Bannow CA, Lund ET, Mathews WR. Identification of a novel mitochondrial protein (“mitoNEET”) cross-linked specifically by a thiazolidinedione photoprobe. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E252–E260. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00424.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart RE, Singleton FL, Hind JS. A comparison of bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid and ferrozine as chelators of iron(II) in reduction reactions. Anal Biochem. 1993;211:151–155. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuajungco MP, Lees GJ. Zinc metabolism in the brain: relevance to human neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 1997;4:137–169. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duce JA, Tsatsanis A, Cater MA, James SA, Robb E, Wikhe K, Leong SL, Perez K, Johanssen T, Greenough MA, Cho HH, Galatis D, Moir RD, Masters CL, McLean C, Tanzi RE, Cappai R, Barnham KJ, Ciccotosto GD, Rogersh JT, Bush AI. Iron-export ferroxidase activity of beta-amyloid precursor protein is inhibited by zinc in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2010;142:857–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X, Liu R, Ross S, Smart EJ, Zhu H, Gong W. Crystallographic studies of human mitoNEET. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33242–33246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge S, Nunez-Ramirez R, Llorca O, Pellegrini L. 3D Architecture of DNA Pol alpha reveals the functional core of multi-subunit replicative polymerases. EMBO J. 2009;28:1978–1987. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J-Y, Suh SW, Gwag BJ, He YY, Hsu CY, Choi DW. The role of zinc in selective neuronal death after transient global cerebral ischemia. Science. 1996;272:1013–1016. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire J, Mailloux R, Appanna VD. Zinc toxicity alters mitochondrial metabolism and leads to decreased ATP production in hepatocytes. J Appl Toxicol. 2008;28:175–182. doi: 10.1002/jat.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R. Function and biogenesis of iron–sulphur proteins. Nature. 2009;460:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nature08301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Zhou T, Ye K, Wang J. Crystal structure of human mitoNEET reveals distinct groups of iron–sulfur proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14640–14645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702426104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Zhang L, Lai S, Ye K. Structure and molecular evolution of CDGSH iron-sulfur domains. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Oganesyan N, Shin DH, Jancarik J, Yokota H, Kim R, Kim SH. Structural characterization of an iron– sulfur cluster assembly protein IscU in a zinc-bound form. Proteins. 2005;59:875–881. doi: 10.1002/prot.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netz DJA, Stith CM, Stümpfig M, Köpf G, Vogel D, Genau HM, Stodola JL, Lill R, Burgers PMJ, Pierik AJ. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases require an iron–sulfur cluster for the formation of active complexes. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:125–132. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock ML, Wiley SE, Axelrod HL, Cohen AE, Roy M, Abresch EC, Capraro D, Murphy AN, Nechushtai R, Dixon JE, Jennings PA. MitoNEET is a uniquely folded 2Fe 2S outer mitochondrial membrane protein stabilized by pioglitazone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14342–14347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707189104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani MA, Casamayor A, Serrano R, Atrian S, Arino J. Disruption of iron homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by high zinc levels: a genome-wide study. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:521–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramelot TA, Cort JR, Goldsmith-Fischman S, Kornhaber GJ, Xiao R, Shastry R, Acton TB, Honig B, Montelione GT, Kennedy MA. Solution NMR structure of the iron– sulfur cluster assembly protein U (IscU) with zinc bound at the active site. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:567–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raulfs EC, O’Carroll IP, Dos Santos PC, Unciuleac MC, Dean DR. In vivo iron–sulfur cluster formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8591–8596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803173105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault TA, Tong WH. Iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis and human disease. Trends Genet. 2008;24:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley MS, Hirst J. The inhibition of mitochondrial complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) by Zn2+ J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34803–34809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirrell TF, Paddock ML, Conlan AR, Smoll EJ, Jr, Nechushtai R, Jennings PA, Kim JE. Resonance Raman studies of the (His)(Cys)(3) 2Fe–2S cluster of mitoNEET: comparison to the (Cys)(4) mutant and implications of the effects of pH on the labile metal center. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4747–4752. doi: 10.1021/bi900028r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Huang H, Tan G, Si F, Liu M, Landry AP, Lu J, Ding H. In vivo evidence for the iron binding activity of an iron–sulfur cluster assembly protein IscA in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 2010;432:429–436. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SE, Murphy AN, Ross SA, van der Geer P, Dixon JE. MitoNEET is an iron-containing outer mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates oxidative capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007a;104:5318–5323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701078104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SE, Paddock ML, Abresch EC, Gross L, van der Geer P, Nechushtai R, Murphy AN, Jennings PA, Dixon JE. The outer mitochondrial membrane protein mitoNEET contains a novel redox-active 2Fe–2S cluster. J Biol Chem. 2007b;282:23745–23749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bitoun JP, Ding H. Interplay of IscA and IscU in biogenesis of iron–sulfur clusters. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27956–27963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Cash VL, Flint DH, Dean DR. Assembly of iron–sulfur clusters. Identification of an iscSUA-hscBA-fdx gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13264–13272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Lin J, Feng Y, Wang J. Binding of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate destabilizes the iron–sulfur clusters of human mitoNEET. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9604–9612. doi: 10.1021/bi101168c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuris JA, Harir Y, Conlan AR, Shvartsman M, Michaeli D, Tamir S, Paddock ML, Onuchic JN, Mittler R, Cabantchik ZI, Jennings PA, Nechushtai R. Facile transfer of [2Fe–2S] clusters from the diabetes drug target mitoNEET to an apo-acceptor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13047–13052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109986108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuris JA, Ali SS, Yeh H, Nguyen TA, Nechushtai R, Paddock ML, Jennings PA. NADPH inhibits [2Fe–2S] cluster protein transfer from diabetes drug target mitoNEET to an apo-acceptor protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11649–11655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.319731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]