Abstract

Dopamine receptors are divided into two families: D1 including D1 and D5 receptors and D2 including D2, D3 and D4 receptors. The role of dopamine D3 receptors in the brain remains controversial. We found that highly selective D3 antagonists induced positive cerebral blood volume (CBV) changes whereas D3 agonism using 7-OH-DPAT induced negative CBV changes in brain regions including nucleus accumbens, antero-medial striatum, cingulate cortex, thalamus, interpeduncular region and hypothalamus. There was pronounced activation in the hippocampus restricted to the subiculum – the output from the infralimbic cortex and dentate gyrus. At higher doses of D3 agonist, functional changes were differentiated across cortical lamina, with layer V–VI yielding positive CBV changes and layer IV yielding negative CBV changes. These results are consistent with differential D1 and D3 innervation in these layers respectively and provide evidence of D1–D3 receptor interactions. Further, the use of MRI provides a new tool for testing the in vivo selectivity of novel dopaminergic ligands where radiolabels are not available - as in the case of D3 receptors.

Introduction

Dopamine receptors are comprised of two families: the D1/D5 family and the D2 family consisting of D2, D3 and D4 subtypes. Although a great deal is known about D1 and D2 receptor functions, the roles of the D3, D4 and D5 receptors are still being determined. The D3 receptor (D3R) was discovered by Sokoloff and colleagues (Sokoloff et al., 1990) who ascribed both autoreceptor-like function as well as post-synaptic activity to the D3Rs. That study, and subsequent work, using mRNA expression levels, immunohistochemistry and ligand binding have demonstrated a rather circumscribed distribution of the D3 receptors in the brain occurring most densely in the islets of Calleja, the shell of the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercule (Bouthenet et al., 1991; Khan et al., 1998; Sokoloff et al., 1990). Unlike the case for the D4 receptor, the regional distribution of D3 receptors is reasonably consistent when comparing measurements of mRNA expression levels, protein expression or ligand binding.

One of the most important roles of dopamine D2 and D3 receptors is to regulate pre-synaptic dopamine release and synthesis, although the role of the D3 receptor in this regard is still controversial. Many investigators have found D3 receptors modulate regulation of dopamine release and/or synthesis as well as impulse control (Aretha and Galloway, 1996; Rayevsky et al., 1995; Tang et al., 1994). However, experiments in both D3 knockout (Joseph et al., 2002; Koeltzow et al., 1998) and D2 knockout mice (Schmitz et al., 2002) seem to suggest that D3 plays little or only a small role as a release-modulating autoreceptor. Nonetheless, adaptive mechanisms in gene knockout mice can often mask important functions of the gene targets. Clearly more work is needed to characterize and determine the role of D3 receptors in the brain. The highly limbic distribution of the D3 receptor has rendered it an important potential target for drugs targeted towards substance abuse (Andreoli et al., 2003; Bouthenet et al., 1991; Grundt et al., 2007; Meador-Woodruff, 1994; Newman et al., 2005; Schwartz et al., 1998; Xi et al., 2004). In addition, the D3 receptor has recently been discovered to be an important potential mediator of L-DOPA induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease ((Bezard et al., 2003; Bordet et al., 1997; Guillin et al., 2003; Sanchez-Pernaute et al., 2007)).

Recent work has shown that DA function can be evaluated using MRI techniques in rats, monkeys and humans (Breiter et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2005; Chen et al., 1997; Choi et al., 2006; Jenkins et al., 2004; Marota et al., 2000; Nguyen et al., 2000; Risinger et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2001). These data demonstrate that maps of ligands such as cocaine, amphetamine and apomorphine lead to large changes in dopaminergic regions as well as in associated circuitry. In particular, dopamine D1 receptor agonism leads to positive hemodynamic changes (Choi et al., 2006) and D1 antagonism leads to negative hemodynamic changes (Marota et al., 2000; Choi et al., 2006), while D2/D3 agonism leads to negative hemodynamic changes (Black et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006). Fewer studies have examined D3 receptors. A PET study showed decreased CBF in a number of brain regions in response to the D3 preferring agonist pramipexole (Black et al., 2002), while we showed decreased CBV in response to the D3 agonist 7-hydroxy-DPAT (Choi et al. 2006). Neither of the latter studies examined the effects of D3 antagonism nor the effects of dose dependencies.

In this work we utilized pharmacologic MRI (phMRI) with the IRON technique (Increased Relaxivity for Optimized Neuroimaging) to assess the response to D3 agonism and D3 antagonism as a function of dose. We then compared the maps of functional changes in functional cerebral blood volume (fCBV) changes induced by these drugs to prior literature on the distribution of D3 receptors using mRNA expression levels as well as protein and ligand binding. The results indicate that the phMRI maps are broadly consistent with the prior distributions reported, but the maps can also elucidate functional responses in downstream circuitry. This in turn provides a highly useful novel tool for evaluation of newly synthesized drugs where in vivo selectivity for the specific dopamine receptors may not yet be established.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult, male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Willmington, MA). Animals were anesthetized with 1.2% halothane in a 1:2 mixture of N2O and O2. The tail vein was catheterized for both contrast agent and drug administration. Body temperature was regulated using a circulating warm water blanket set to 37°C. Arterial blood gas sampling and blood pressure were measured by catheterization of the femoral artery in some instances, or using non-invasive blood pressure monitoring with an inflating tail cuffs (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Contrast agent

phMRI measurements were made using a dextran-coated superparamagnetic intravascular contrast agent of monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticle (MION) (Shen et al., 1993; Weissleder et al., 1990). MION was synthesized at the Martinos Center at Massachusetts General Hospital. It has recently been demonstrated that the iron oxide method or IRON (Increased Relaxation for Optimized Neuroimaging) greatly improves the contrast to noise ratio (CNR) in both phMRI and traditional fMRI studies in animals (Chen et al., 2001; Dubowitz et al., 2001; Mandeville et al., 2004; Mandeville et al., 2001). The use of the IRON method allows the measurement of fCBV changes, a physiologically relevant parameter, and also allows for comparisons of data collected at different field strengths (Mandeville et al., 2004).

Pharmacological ligands

We use two different D3 antagonists. A water soluble agent N-(4-(4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-trans-but-2-enyl)-4-pyridine-2-enylbenzamide) (PG-01037 (Grundt et al., 2005; Grundt et al., 2007) was obtained from Drs. Peter Grundt and Amy Newman from the Medicinal Chemistry Section of NIDA. A non-water soluble agent (trans-N-[4-[2-(6-cyano-1,2,3, 4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-2-yl)ethyl]cyclohexyl]-4-quinolininecarboxamide) (SB-277011) was obtained from GlaxoSmithKline laboratories (Reavill et al., 2000). Both agents were reported to cross the blood brain barrier (Grundt et al., 2007). We used the common D3 agonist 7-hydroxy-N,N-di-n-propyl-2-aminotetralin (7-OH-DPAT) obtained from SIGMARBI (St. Louis, MO). Although PG-01037 is water soluble we found that it precipitated when taken up in heparinized saline (2units/ml). In non-heparinized saline it was quite soluble at the doses used, and all studies were performed after i.v. administration of PG-01037 in saline. The SB-277011 is not water soluble, and thus we administered this compound as a slurry in methylcellulose at a single i.p. dose of 10mg/kg. The 7-OH-DPAT was administered i.v. in heparinized saline.

Pharmacological MRI (phMRI)

phMRI images were acquired from a 9.4T Bruker (Billerica, MA) console with a Magnex (Oxford, UK) magnet, Or from a 4.7T magnet (for the D3 antagonist SB-277011) with a Bruker console and an Oxford magnet. We followed the same protocol as published earlier for the phMRI studies (Chen et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006; Mandeville et al., 2004). Briefly, conventional gradient echo sequence with TR/TE of 500/7.6 ms was used to acquire phMRI data. Eighteen contiguous coronal slices were obtained for each time point with in-plane spatial resolution of 0.2 × 0.2 mm2 and a 0.75 mm slice thickness. The temporal resolution was 64s per image set.

The use of the IRON technique allows for comparisons at different field strengths since the change in CBV (fCBV) measured using this technique are independent of field strength (Mandeville et al., 2004). Images were acquired serially without interruption for over 2 hours. A minimum of 4 baseline points were acquired before the injection of MION contrast agent and a minimum of 25 post-contrast baseline points were acquired before the administration of drugs.

To assess the effects of the D3 antagonists and agonist on blood pressure, measurements (mm Hg) were made using either direct arterial sampling of pressure or a non-invasive measurement from the tail (Kent Scientific, CT). For the D3 antagonist there were no significant effects on blood pressure (mm Hg) at any time points or doses (ANOVA p > 0.9). The measurements were: baseline pressure = 102.6 ± 14.5; 1 min post-drug = 97.9±12.9 (p<0.2); 5 min = 100.1±15.3 (P <0.3); 30 min = 100.9± 17.1 (p <0.6).

For the D3 agonist 7-OH-DPAT there was a small transient effect on blood pressure that was significant as follows (doses 0.1–0.5mg/kg): baseline pressure = 102.3 ± 18.8; 1 min = 94.5±15.4 (p<0.01); 5 min = 94.9±17.1 (P <0.01); 30 min = 98.0± 16.5 (p <0.06). At doses higher than 1.5mg/kg there was no drop in blood pressure and no significant change as a function of time – perhaps because of the balance between D3 and D1 vascular effects (vide infra). The small decrease in blood pressure would not be expected to cause any changes that would result in alterations in cerebrovascular autoregulation. Data collected in rats shows that changes in blood pressure have little effect on basal CBV or CBF until pressure drops to about 65 mm Hg (Zaharchuk et al., 1999). Due to the large weighting of BOLD signal by veins it is not impossible that BOLD signal measurements could be affected by small, rapid changes in blood pressure (Kalisch et al., 2001), although such changes are not reflective of tissue perfusion. The use of the IRON technique obviates this confound (Mandeville et al., 2004). A recent study of the effects of blood pressure changes during phMRI also comes to the conclusion that within the autoregulatory regime there is little effect on CBV (Gozzi et al., 2007).

Data Analysis

Image Co-registration

To facilitate comparisons between different groups of animals, all images were registered onto the same standard brain template for subsequent averaging across animals as previously described (Liu et al., 2007). The data were resliced to a thickness of 0.5 mm. Since motion during a functional scan was not a consideration due to anesthesia and the use of a head holder, registration parameters were determined for each functional scan using a single full brain volume that was the average of all time points after MION injection but prior to drug injection. These registration parameters were then applied to all time points in the functional data set. Registration between the functional image set and the standard template was performed by adjusting 12 registration variables in a standard affine transformation as generally applied in human studies. The template images were consistent with the stereotactic coordinate system atlas from Paxinos (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Then regions of interest (ROIs) can be drawn for any of the regions defined in the atlas.

Functional Analysis

Maps of percent CBV changes were obtained by converting signal intensity changes to ΔR2* on a pixel by pixel basis (Chen et al., 2001) and assuming a linear relationship between R2* relaxivity and blood volume (Villringer et al., 1988). The fCBV was defined as a percent change from baseline (ΔCBV) and then averaged over a given time interval as in equation [1] below where A = 30 min after D3 drug injection. Maps of the difference in average ΔCBV were made for experiments where we injected either a D3 agonist followed by a D3 antagonist or vice versa. For these experiments, we used the average ΔCBV of the initial drug alone from time point 0 to A = 30 min and then used equations [2,3] below to calculate the percent change in the average ΔCBV from time A (where either D3 agonist or antagonist is injected) to B = 50 min following the second drug injection of agonist or antagonist.

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

Statistics

Between group comparisons were made using a one-way ANOVA with dose and brain region. Errors reported are standard errors of the mean.

Results

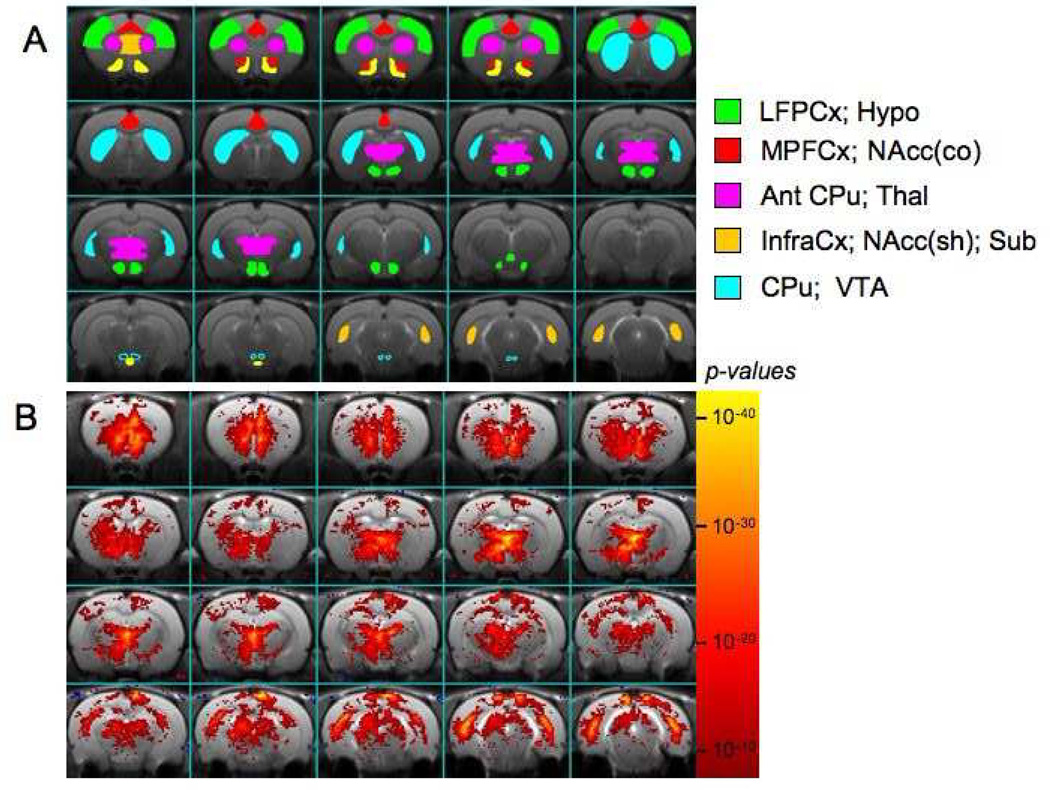

D3 selective antagonist PG-01037

We studied two different D3 selctive antagonists PG-01037 and SB-277011. PG-01037 is a water-soluble antagonist with nanomolar in vitro affinity for the D3 receptor (Grundt et al., 2005; Grundt et al., 2007). Shown in Fig. 1a are the major regions of interest used in the analysis registered to the template brain to which all the studies were aligned. A map of significant changes in fCBV induced by 2mg/kg of PG-01037 averaged from 10 rats, is shown in Fig. 1b. Prominent positive fCBV changes are induced in a number of different brain regions including the accumbens, thalamus and subiculum (CA1 region of Ammon’s horn). In order to see the activation in the ventral striatum and accumbens more accurately, Fig. 2a shows three slices from the region of the nucleus accumbens with an overlay of a registered rat brain outline including the accumbens core and shell. There are larger fCBV changes in the shell of the accumbens compared to the core or the caudate/putamen. Intravenous administration of the PG10-01037 compound leads to immediate signal increases with a flat peak that lasts for over 35 min. The fCBV changes have still not returned to baseline by about 80 min. In order to see if the pattern of fCBV changes induced by this compound was similar to the distribution of D3 receptors we show a comparison of the average fCBV change over 40 min in various brain regions with data from Richtand et al. (Richtand et al., 1995) using quantitative values for mRNA expression in various brain regions. By chance the absolute magnitude of the units chosen for the mRNA expression and the fCBV changes match closely. It is seen that the overall pattern of activity is reasonably similar (Fig. 2c). In the Richtand et al. paper (Richtand et al., 1995) the mRNA was described as originating from the hippocampus without specification of region. We find much stronger activation in the subiculum/dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus consistent with its connections to infra-limbic cortex – the latter region also being strongly activated by both D3 antagonists (see Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Maps of D3 antagonist PG-01037. A) The regions of interest (ROIs) used in the quantitative analysis are shown on a high resolution T2 image to which all the brains were registered. B) Average map of statistically significant changes in fCBV induced by 2.6 mg/kg of PG-01037 (n=13) using a fit to a general linear model. Numerous brain regions show a strong response, but there is a much larger response in the shell of the accumbens than in the caudate/putamen indicating the high D3 selectivity of this compound.

Fig. 2.

Selectivity in the nucleus accumbens in the response to PG-01037. A) Three slices from a study of 2mg/kg of PG-01037 with a registered brain atlas showing the nucleus accumbens in green and the caudate/putamen in blue. There is a gradient in the caudate/putamen such that there is greater activation in the anteromedial CPu than in the posterior-lateral CPu. B) Average CBV time course for 2.6mg/kg (n=13) of PG-01037 in the nucleus accumbens shell. The CBV change is still elevated at 80 min after i.v. administration. C) Comparison of the average fCBV change over the first 40 min after PG-01037 with mRNA expression of D3R measured by Richtand et al. (Richtand et al., 1995). Just by sheer chance the absolute magnitude of the two metrics agree in the NAc. The overall pattern is similar indicating good D3 selectivity for the PG-01037. D) Although most brain regions did not show a significant effect of dose using ANOVA analysis, the doses can be separated using the averaged CBV values over 40min across brain regions using linear discriminant analysis. The two discriminant functions are plotted with the percent of variance in the data they explained. Function 1 was significant by Wilk’s lamba (p = 0.013) whereas function 2 was not (p = 0.47).

Table 1.

Regional Effects of D3 Ligands on fCBV

| Antagonist: PG01037 | 2.6 mg/kg (n= 13) | 5.3 mg/kg (n=9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infralimbic Cortex | 5.62±0.34 | 6.32±0.77 | ||

| Cingulate* | 3.95±0.40 | 2.56±0.65* | ||

| VTA | 2.76±0.43 | 2.04±0.83 | ||

| VMH* | 3.22±0.31 | 6.81±4.28* | ||

| VMStr | 5.44±0.51 | 4.58±0.67 | ||

| DLStr | 4.28±0.17 | 3.52±0.56 | ||

| NACCshell | 10.37±0.68 | 9.04±0.68 | ||

| NACCcore | 7.04±0.34 | 6.27±0.56 | ||

| Islets of Calleja | 10.98±0.56 | 10.5±0.98 | ||

| LPFCortex* | 2.69±0.34 | 4.53±1.04 | ||

| Medial Thalamus | 9.67±0.57 | 10.01±0.62 | ||

| Subiculum | 9.77±0.64 | 11.17±0.69 | ||

| Hippocampus | 4.32±0.55 | 3.75±0.78 | ||

| Agonist: 7-OHDPAT | 0.1mg/kg (n=4) | 0.25 mg/kg (n=6) | 0.5mg/kg (n=4) | 1.5mg/kg (n=4) |

| Infralimbic | −2.67±0.64 | −3.60±1.39 | −6.13±0.32 | −8.48±1.03 |

| Cortex*** | ||||

| Cingulate** | −2.97±0.99 | −7.86±2.50 | −3.13±0.67 | −6.73±1.13 |

| VTA*** | −2.40±0.52 | −7.14±2.37 | −6.05±0.34 | −8.15±0.83 |

| VMH** | −1.67±2.08 | −12.22±3.87 | −8.30±2.24 | −11.55±2.33 |

| VMStr** | −5.63±0.85 | −7.73±1.62 | −5.86±0.72 | −10.10±2.37 |

| DLStr* | −3.67±0.29 | −5.58±1.18 | −4.45±0.66 | −5.55±0.62 |

| NACCshell*** | −4.57±0.50 | −11.44±2.32 | −7.80±1.67 | −11.78±1.01 |

| NACCcore*** | −4.30±0.92 | −8.70±2.76 | −7.28±0.43 | −8.58±0.60 |

| Islets of Calleja*** | −3.63±0.55 | −10.94±1.40 | −8.95±0.60 | −10.23±1.59 |

| LPFCortex*** | −2.30±0.79 | −5.90±1.84 | −4.25±0.47 | 6.55±0.45 |

| Medial Thalamus*** | −1.83±1.12 | −8.22±1.79 | −4.08±0.95 | −8.48±1.31 |

| Subiculum*** | −1.97±1.70 | −8.80±2.42 | −6.25±1.21 | −9.33±1.31 |

| Interpeduncular*** | −3.90±0.30 | −7.36±1.32 | −7.75±0.60 | −9.18±1.92 |

Significant effect of dose in brain region using univariate ANOVA(

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001).

Given that reliable separation of objects in an image requires at least two pixels across an object, the islets of Calleja, a region often described to be very dense in D3 receptors cannot reliably be separated from other structures, such as the septum. The size of the largest segments of the islets of Calleja (where individual segments can be up to 0.15×1×0.2mm) is on the order of our average voxel size (0.21mm×0.21mm×0.75mm). Nonetheless, there are very strong changes in fCBV in the region of the islet of Calleja that are not inconsistent with activation of this structure. We have reported this area in Table 1 with the caveat that this region also includes some septum and accumbens. This is confirmed by simulations using a point spread function appropriate for these images and convolving that with an ROI drawn for the islets of Calleja.

We studied doses between 2–6mg/kg i.v. In this dose range, in most brain regions, there was more variability between animals than between doses. The brain regions that showed a significant effect of dose were cingulate, ventromedial hypothalamus, posterior lateral caudate putamen and lateral frontoparietal cortex. A full description of the fCBV changes observed is shown in Table 1. Although most of the brain regions did not show a significant dose effect, we were able to segregate the doses using linear discriminant analysis (Fig. 2d)

D3 selective antagonist SB-277011

This compound is reported to have 100-fold selectivity for D3 receptors over D2 receptors in in vitro testing (Reavill et al., 2000). Further, it was reported to increase amphetamine-induced changes in medial prefrontal cortex and accumbens (Schwarz A. et al., 2004). It is also reported to reduce cocaine-seeking behaviors in rats (Di Ciano et al., 2003; Vorel et al., 2002). The drug is insoluble in water and so we injected it i.p. in methylcellulose. Our data shows that SB-277011 produces a large increase in fCBV in the MPFCx, NAc and thalamus for a dose of 10mg/kg i.p. (Fig. 3a). The time course for these changes shows a return to baseline in about 40 min (Fig. 3b). Unlike for PG-01037 the largest change is induced in the MPFCx and infralimbic cortex. Similar to PG-01037 there is large activation in the nucleus accumbens and thalamus and much less in caudate/putamen.

Fig. 3.

Maps of D3 antagonist SB-277011A. A) Map of statistically significant changes in fCBV after administration of 10mg/kg i.p. of the D3 antagonist SB-277011A. There is a large response in NAc and little in the CPu. In contrast to the PG-01037 the largest response is in the medial prefrontal cortex. B) Averaged fCBV response after i.p. administration of SB-277011A (n=7). The signal has returned to baseline after approximately 40min.

D3 preferring agonist 7-OH-DPAT

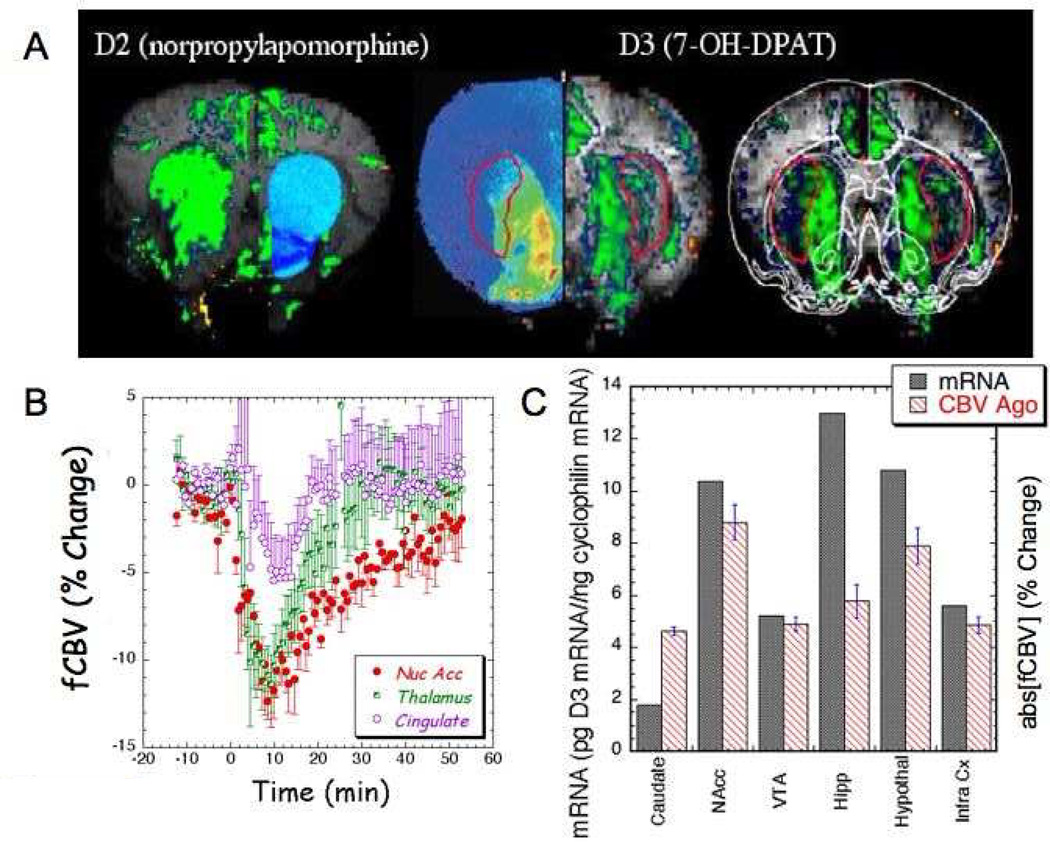

We used 7-OH-DPAT since this compound is the most commonly used D3 agonist. This drug binds to D3 receptors with subnanomolar affinity and has been reported to show a selectivity of 100-fold for D3 over D2 receptors in vitro (Levesque et al., 1992), however there is some controversy over its in vivo selectivity based upon behavioral measures (Baker et al., 1999; Katz and Alling, 2000; Pritchard et al., 2003). We therefore decided to utilize phMRI to measure fCBV changes induced by 7-OH-DPAT to help assess its in vivo selectivity. Fig. 4 shows maps of fCBV changes induced by an acute dose of 0.1 mg/kg 7-OH-DPAT as well as a map of the fCBV changes induced by 0.5mg/kg. Since the number of animals was different for the two doses, we used maps of the fCBV, which are independent of n, rather than the statistical maps shown in the previous figures. Large changes in fCBV are induced in the nucleus accumbens and thalamus with smaller, but robust changes in the MPFCx and striatum. Shown in Fig. 5 are regional and temporal comparisons of receptor activity between this D3 agonist and a D2 selective agonist (norpropylapomorphine). Also shown in Fig. 5a are data from a single animal with a registered overlay from a rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Alongside the fCBV map is a map of autoradiographically labeled 7-OH-DPAT taken from a paper published by Neisewander et al. (Neisewander et al., 2004) that is shown side-by-side with the CBV map for comparative purposes. It can be seen that there is much less activation in the caudate putamen (shown in the red outline than for the accumbens illustrating the selectivity of the 7-OH-DPAT for D3 receptors. The time courses for the fCBV changes are also shown in Fig. 5 as well as the absolute value of the average fCBV changes induced between 0 and 30 minutes, again compared to the mRNA expression levels reported by Richtand et al. (Richtand et al., 1995) similar to the D3 antagonist above. The time to return to baseline is shorter in the cingulate and thalamus. The full width half maximum (FWHM) of the average fCBV curves is 22.8, 13.9 and 9.6 min respectively for the accumbens, thalamus and cingulate.

Fig. 4.

Maps of responses to two doses of the D3 agonist 7-OH-DPAT. A) Averaged map of statistically significant fCBV changes to 0.1 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT (n=4). The largest responses are noted in the NAc and the anteromedial CPu. B) Averaged map of statistically significant fCBV changes to 0.5 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT (n=5). There is a greater response in numerous regions of the brain reflecting the large dose dependence noted with this drug compared to the D3 antagonist.

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of D3 agonist maps to autoradiography and D2 agonist. A) On the top left is a map of significant changes in CBV induced by 2mg/kg of the D2 agonist norpropylapomorhine compared to an overlay from D2 autoradiography. Data is taken from (Choi et al., 2006). In the middle is a comparison of the fCBV response to 0.2mg/kg of 7-OHDPAT in a single animal to an autoradiogram taken using labeled 7-OH-DPAT by Neisewander et al. (Neisewander et al., 2004) with permission of the publisher. The autoradiogram (left side of image) was scanned from the paper by Neisewander et al. and aligned as best as possible to the MRI. The CPu is shown in the red outline showing the large gradient from NAc to CPu. On the right is the CBV map shown with an outline of a registered rat atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). B) Averaged time course of fCBV changes induced by 0.25 mg/kg 7-OH-DPAT (n=10). Note the fCBV changes are negative compared to the positive changes induced by D3 antagonism. C) Comparison of the absolute value of the average fCBV change over the first 30 min after 7-OH-DPAT with mRNA expression of D3R measured by Richtand et al. (Richtand et al., 1995).

Unlike for the D3 antagonist, there is a strong dose dependence for most brain regions with 7-OH-DPAT. Most surprising, is that higher doses of 7-OH-DPAT produce a cortical response that is differentiated by laminae with positive fCBV changes in layers V and VI of the cortex, and negative fCBV changes in layers III and IV of cortex. These effects are shown in Fig. 6 along with maps of mRNA expression and ligand binding for D3 receptors (in layer IV) and mRNA expression levels for D1 receptors (in layers V and VI) and taken from Gurevich and Joyce (Gurevich and Joyce, 2000). The fCBV changes induced in these layers is shown in Fig. 6c,d showing the clear laminar dichotomy between the positive and negative fCBV changes. Laminae also exhibit different temporal responses: the positive fCBV change in layer V–VI has a FWHM of 7 min and the negative change in layer IV has a FWHM of 23 min (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Cortical layer specificity of high doses of 7-OH-DPAT. A) Figure taken from Fig. 2a of Gurevich and Joyce (Gurevich and Joyce, 2000) with permission of the publisher. On the top left the left hemisphere shows specific binding to D3R and the right hemisphere is the mRNA expression of D3R. Both are greatest in layer IV of cortex. On the top right is a figure taken from Fig. 8 of (Gurevich and Joyce, 2000) showing the layer specificity of D1R mRNA expression in layers V–VI of cortex. B) Averaged map (n=5) of CBV changes induced by 1.5 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT. Note the large activation in basal ganglia and the negative D3-like CBV in layers III–IV and the postive D1-like CBV changes in layers V–VI. C) Averaged CBV time course for activation in layers IV and V for 1.5mg/kg 7-OH-DPAT. D) Plot of the fCBV values as a function of distance normal to the cortical surface. The values represent the averages over a 1mm slice interval from bregma (+1.2-0.2) and the identification of the layers follows that drawn in the Paxinos and Watson atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1998).

Functional D3 selectivity

Since D3 expression levels in normal animals are much stronger in the shell of the accumbens (NAc) than in the caudate/putamen (CPu), it is appropriate to use some sort of ratio of the induced fCBV changes in the latter two regions as a metric for the in vivo “functional” selectivity of each drug. For D1 and D2 receptor ligands that we have assessed previously, this ratio is quite close to 1 (Chen Y. C. et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006) which is consistent with the reported distributions of the D1 and D2 receptors (Cooper et al., 2003). For the purposes of this manuscript we chose a simple ratio of the ΔfCBV in NAc/CP. The higher the ratio, the greater the in vivo selectivity for D3 over D2. The ratio of the NAc/CP for 7-OH-DPAT at a dose of 0.1–0.3 mg/kg is 1.9 ± 0.5 versus 2.5±0.3 for PG-01037 at a dose of 2–3 mg/kg (p<0.01) demonstrating the higher selectivity of the latter ligand in this dose range.

Combined studies of D3 agonist and antagonist

We studied the effects of pre-and post-treatment with D3 antagonist and D3 agonist of each drug together. We performed a continuous imaging experiment where administration of 2mg/kg PG-01037 was followed 30 min later by 0.2 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT. The 7-OH-DPAT leads to immediate reversal of the positive fCBV changes induced by the D3 antagonist in most brain regions. A subtraction map of the effects of PG-01037 minus those of 7-OH-DPAT is shown in Fig. 7a. Since the CBV effects of the antagonist are positive and those of the agonist are negative (Fig. 7b), the subtraction map shows positive values. This map thus represents those regions that are most strongly targeted by both drugs (i.e. similar to a conjunction map). As shown for the individual drugs, the differential response exhibits a strong gradient from accumbens to caudate/putamen and very large values in the hypothalamus and interpeduncular region. Performing the experiments in the reverse manner with 0.2mg of 7-OH-DPAT followed by 2mg/kg of PG-01037 showed almost a complete blockade of the positive fCBV changes induced by the D3 antagonist (Fig. 7c). These experiments serve to show that at these doses the functional effects of the D3 receptor agonist supersedes those of the D3 antagonist.

Fig. 7.

Interactions of D3 agonist and antagonist. A) Subtraction map of CBV changes induced by 3 mg/kg of PG-01037 in the first 30 minutes followed by 0.2mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT in the following 30 min. Since the subtraction is a positive CBV change minus a negative CBV change the result is positive and is essentially a conjunction map of the two drugs. The strongest effects were seen in the NAc, medial hypothalamus and interpeduncular regions. B) Plot of the averaged fCBV timecourse from the NAc. The agonist immediately turns off the antagonist. C) A bar graph of the brain regional effects of the antagonist preceded by the agonist (n=5). The agonist at this dose (0.2mg/kg) blocks the antagonist (3 mg/kg) in most brain regions. D) A bar graph of the regional effects of the antagonist first (3mg/kg) upon the agonist (0.2mg/kg) (n=5). At this dose the antagonist does not block the effects of the agonist in most brain regions.

*** P< 0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05.

Cing – anterior cingulate; VMH ventromedial hypothalamus; VMStr medial caudate/putamen; Shell – shell of the NAc; LFPCx – lateral frontoparietal cortex.

Discussion

These results indicate the utility of in vivo, non-invasive imaging methods for the determination of the receptor selectivity of dopaminergic drugs. Consistent with prior studies we found that D2/D3 agonists lead to decreased fCBV in rodents (Chen Y. C. et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006) and primates (Sanchez-Pernaute et al., 2007). Both of the two highly selective D3 antagonists studied led to increased fCBV in brain regions that are largely consistent with the limbic D3 circuitry. We found the interpeduncular region to be strongly affected by the D3 drugs (see Fig. 7). This region has not previously been described in detail with regards to D3 receptors. The sole reference we could find was a comparative study where the interpeduncular region was found to bind D3 antagonist in rabbits but not rodents (Levant, 1998). In a recent paper examining the modulation of the amphetamine limbic correlations using D3 antagonism it was claimed that there was negative modulation of VTA by D3 antagonism (Schwarz A. J. et al., 2007). The VTA and the interpeduncular region are hard to separate therefore it is possible that what we have labeled interpeduncular could also include some VTA as well (the converse is also true). The robust activation in the subiculum region of the hippocampus (CA1 field of Ammon’s horn) which also includes some dentate gyrus activation as well, is consistent with the limbic distribution of the D3 receptors and the strong innervation of infralimbic cortex from this region (Swanson, 1981). This specific selectivity within the hippocampus for D3 receptors has not been described previously, but the result is consistent with the large CBV changes within infralimbic cortex (Fig. 1; Table 1) and the known connectivity with the subiculum.

The relative selectivity for D3 over D2 for each ligand can be inferred in a functional manner in these studies. Consistent with prior behavioral studies we found that 7-OH-DPAT can target both the caudate/putamen as well as the nucleus accumbens with a ratio of 1.9 for the induced changes in fCBV in NAc/CPu. This accords with behavioral studies showing inhibition of locomotor activity in wild-type mice at low doses, but no effects in D3-knockout mice (Pritchard et al., 2003). These data suggest that in vivo this ligand is selective for D3 over D2, although the activation seen in CPu would suggest some D2 activity consistent with prior behavioral studies in D2 knockout mice showing that 7-OH-DPAT is still half as effective at inhibition of locomotor activity as it is in wild-type mice (Boulay et al., 1999). The two antagonists, at the doses administered, show more selectivity than the agonist producing ratios of NAc/CP of 2.2 and 2.5 respectively for the SB-277011 and PG-01037 in agreement with the highly selective D3/D2 ratio seen in binding assays in vitro (Grundt et al., 2007; Reavill et al., 2000). It should be pointed out that although the in vitro affinities are much higher for D3 than D2, in vivo the much higher D2 receptor density (Bmax) will lead to activation of these receptors as well as the D3 receptors.

The utility of the phMRI in characterization of the in vivo specificity of the novel D3 ligands shows great promise. The maps generated of the PG-01037 are quite consonant with D3 receptor circuitry (see Figs. 1,2,7). Therefore it is likely that these types of experiments will prove invaluable for characterization of novel ligands without the necessity of creating radiolabeled ligands, a task that, thus far, has proved elusive for D3 receptors. Balancing this potential is the fact that it is still difficult to convert an hemodynamic metric into a quantitative value representing receptor affinity – something that is still the provenance of radiolabeled ligands. Nevertheless, when combined with the in vitro binding assays, maps of the type generated here provide a compelling case for in vivo D3 selectivity of the ligands studied here, and such information will undoubtedly be useful in combination with behavioral studies.

The ability of 7-OH-DPAT at 0.2mg/kg to block the fCBV effects of PG-01037 at 2mg/kg (and the inability of PG-01037 to block 7-OH-DPAT) suggests that there is higher occupancy of the former at the dose administered. This fact is commensurate with the observation that large i.p doses of PG-01037 are needed to obtain D3-specific behaviors (Collins et al., 2007). However, the fact that we see robust activation at 2mg/kg i.v. (much lower than the i.p. doses) suggests that peripheral metabolism is an important determinant of the final brain concentrations obtained. Pharmacokinetic studies in rats are underway for PG-01037 to specifically address this subject. It should be noted that large discrepancies (a factor of ten) between the effective doses for i.p. and i.v. administration are also seen for drugs such as cocaine (Porrino, 1993) and methylphenidate.

We did not perform dose-dependencies for the SB-277011 since its insolubility in water makes determination of the exact dose delivered difficult (this compound was administered i.p. in methylcellulose). For the PG-01037 we found a limited response to dose between 2–6mg/kg. Using linear discriminant analysis we can separate the doses into groups that showed good separation between the high (5–6mg/kg) and low (2–3mg/kg) doses (Fig. 2d), but the effects of dose in this range were small. This stands in contrast to 7-OH-DPAT where large dose dependencies are noted across the dose range (see Table 1). Prior behavioral studies in rats indicated that low doses of 7-OH-DPAT inhibit locomotor activity, whereas high doses potentiate it (Ahlenius and Salmi, 1994; Ferrari and Giuliani, 1995; Svensson et al., 1994) suggesting either two classes of D3 receptor (pre- and post-synaptic) or stimulation of other receptors – such as D1.

The latter points lead to perhaps one of the more exciting findings of this study -that is the ability to detect signals of opposite signs in the cortical layers using high doses (≥1.5 mg/kg) of the D3 agonist 7-OH-DPAT. Our prior study showed that D1 agonists increase fCBV, while D2/D3 agonists decrease fCBV (Chen et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006). Using moderately high spatial resolution (0.21×0.21×0.75 mm) we found that cortical layers V–VI showed positive fCBV changes while layers III–IV showed negative fCBV changes. These results are consistent with histological data obtained by Gurevich and Joyce (Gurevich and Joyce, 2000). In that paper they showed that D3 receptors, as measured by both ligand binding or mRNA expression, were found in layer IV of barrel cortex. Further, they found that none of the other DA receptors were expressed in layer IV. Conversely, there was high expression of D1 receptors in infragranular regions – especially in layer VIb. Similar results were found in adult rats where neurons containing D1 mRNA were most abundant in layer VIb – but were also found in layers VIa and V (Gaspar et al., 1995). These findings are thus consistent with the location of positive fCBV changes we see in layers V–VI; i.e. more ventral than the negative fCBV changes. Interestingly, the time courses of these fCBV changes are different (see Fig. 6d), again suggesting that they arise from different neuronal populations. The stimulation of D1 activity with a D3 agonist is not unprecedented – we found that administration of 7-OHDPAT led to positive fCBV changes in Parkinsonian monkeys with dyskinesia compared to the negative fCBV changes induced in Parkinsonian monkeys without dyskinesias or in normal controls (Sanchez-Pernaute et al., 2007). These observations are consistent with D3 upregulation in motor striatum signaling through D1 pathways on neurons that co-express D3 (Schwartz et al., 1998), and further support strong interactions between D1 and D3 receptors. Further studies with higher spatial resolution are warranted to more accurately characterize the laminar specificity of these signals.

Although hemodynamic metrics can be considered to be an indirect reflection of receptor binding, and are often difficult to interpret, they also represent a transduction mechanism that is sensitive to synaptic signaling processes (Attwell and Iadecola, 2002) in addition to the direct effects of neurotransmitters such as dopamine. We found that D3 receptors are heavily expressed in astrocytes - and lead to vasoconstriction – but unlike D1 and D5 receptors were not present on capillaries or microvessels (Choi et al., 2006). The CBV changes we observed are entirely consistent with the effects of D1, D2, and D3 receptors upon adenylate cyclase activity and Gprotein coupling. Therefore, they likely represent a level of sensitivity that should prove quite useful for examination of any number of dopaminergic ligands. Further, the ability to determine whole brain activity, as well as pharmacodynamic profiles, will enable much more detailed characterization of novel dopaminergic ligands where radiolabled versions do not exist.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH/NIDA DA16187-06

References

- Ahlenius S, Salmi P. Behavioral and biochemical effects of the dopamine D3 receptor-selective ligand, 7-OH-DPAT, in the normal and the reserpine-treated rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;260:177–181. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoli M, Tessari M, Pilla M, Valerio E, Hagan JJ, Heidbreder CA. Selective antagonism at dopamine D3 receptors prevents nicotine-triggered relapse to nicotine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1272–1280. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aretha CW, Galloway MP. Dopamine autoreceptor reserve in vitro: possible role of dopamine D3 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;305:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Iadecola C. The neural basis of functional brain imaging signals. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:621–625. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LE, Hood CA, Heidema AM. Assessment of D3 versus D2 receptor modulation of the discriminative stimulus effects of (+)-7-OH-DPAT in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10:717–722. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezard E, Ferry S, Mach U, Stark H, Leriche L, Boraud T, et al. Attenuation of levodopa-induced dyskinesia by normalizing dopamine D3 receptor function. Nat Med. 2003;9:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nm875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black KJ, Gado MH, Perlmutter JS. PET measurement of dopamine D2 receptor-mediated changes in striatopallidal function. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3168–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03168.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black KJ, Hershey T, Koller JM, Videen TO, Mintun MA, Price JL, et al. A possible substrate for dopamine-related changes in mood and behavior: prefrontal and limbic effects of a D3-preferring dopamine agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17113–17118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012260599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordet R, Ridray S, Carboni S, Diaz J, Sokoloff P, Schwartz JC. Induction of dopamine D3 receptor expression as a mechanism of behavioral sensitization to levodopa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3363–3367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthenet ML, Souil E, Martres MP, Sokoloff P, Giros B, Schwartz JC. Localization of dopamine D3 receptor mRNA in the rat brain using in situ hybridization histochemistry: comparison with dopamine D2 receptor mRNA. Brain Res. 1991;564:203–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91456-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter H, Gollub R, Weisskoff R, Kennedy D, Makris N, Berke J, et al. Acute Effects of Cocaine on Human Brain Activity and Emotion. Neuron. 1997;19:591–611. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Andersen AH, Zhang Z, Ovadia A, Gash DM, Avison MJ. Mapping drug-induced changes in cerebral R2* by Multiple Gradient Recalled Echo functional MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;14:469–476. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)02100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Choi JK, Andersen SL, Rosen BR, Jenkins BG. Mapping dopamine D2/D3 receptor function using pharmacological magnetic resonance imaging. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:705–715. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Mandeville JB, Nguyen TV, Talele A, Cavagna F, Jenkins BG. Improved mapping of pharmacologically induced neuronal activation using the IRON technique with superparamagnetic blood pool agents. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14:517–524. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YI, Galpern WR, Brownell AL, Matthews RT, Bogdanov M, Isacson O, et al. Detection of dopaminergic neurotransmitter activity using pharmacologic MRI: correlation with PET, microdialysis, and behavioral data. Mag. Reson. Med. 1997;38:389–398. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, Chen YI, Hamel E, Jenkins BG. Brain hemodynamic changes mediated by dopamine receptors: Role of the cerebral microvasculature in dopamine-mediated neurovascular coupling. Neuroimage. 2006;30:700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Newman AH, Grundt P, Rice KC, Husbands SM, Chauvignac C, et al. Yawning and hypothermia in rats: effects of dopamine D3 and D2 agonists and antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH. The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Underwood RJ, Hagan JJ, Everitt BJ. Attenuation of cue-controlled cocaine-seeking by a selective D3 dopamine receptor antagonist SB-277011-A. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:329–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz DJ, Bernheim KA, Chen DY, Bradley WG, Jr, Andersen RA. Enhancing fMRI contrast in awake-behaving primates using intravascular magnetite dextran nanopartieles. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2335–2340. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari F, Giuliani D. Behavioural effects of the dopamine D3 receptor agonist 7-OH-DPAT in rats. Pharmacol Res. 1995;32:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(95)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Bloch B, Le Moine C. D1 and D2 receptor gene expression in the rat frontal cortex: cellular localization in different classes of efferent neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1050–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi A, Ceolin L, Schwarz A, Reese T, Bertani S, Crestan V, et al. A multimodality investigation of cerebral hemodynamics and autoregulation in pharmacological MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt P, Carlson EE, Cao J, Bennett CJ, McElveen E, Taylor M, et al. Novel heterocyclic trans olefin analogues of N-{4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butyl}arylcarboxamides as selective probes with high affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:839–848. doi: 10.1021/jm049465g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt P, Prevatt KM, Cao J, Taylor M, Floresca CZ, Choi JK, et al. Heterocyclic analogues of N-(4-(4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)butyl)arylcarboxamides with functionalized linking chains as novel dopamine D3 receptor ligands: potential substance abuse therapeutic agents. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4135–4146. doi: 10.1021/jm0704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillin O, Griffon N, Bezard E, Leriche L, Diaz J, Gross C, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor controls dopamine D3 receptor expression: therapeutic implications in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;480:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich EV, Joyce JN. Dopamine D(3) receptor is selectively and transiently expressed in the developing whisker barrel cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;420:35–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000424)420:1<35::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins BG, Sanchez-Pernaute R, Brownell AL, Chen YC, Isacson O. Mapping dopamine function in primates using pharmacologic magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9553–9560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1558-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JD, Wang YM, Miles PR, Budygin EA, Picetti R, Gainetdinov RR, et al. Dopamine autoreceptor regulation of release and uptake in mouse brain slices in the absence of D(3) receptors. Neuroscience. 2002;112:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R, Elbel GK, Gossl C, Czisch M, Auer DP. Blood pressure changes induced by arterial blood withdrawal influence bold signal in anesthesized rats at 7 Tesla: implications for pharmacologic mri. Neuroimage. 2001;14:891–898. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Alling KL. Discriminative stimulus effects of putative D3 dopamine receptor agonists in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11:483–493. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan ZU, Gutierrez A, Martin R, Penafiel A, Rivera A, De La Calle A. Differential regional and cellular distribution of dopamine D2-like receptors: an immunocytochemical study of subtype-specific antibodies in rat and human brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:353–371. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981221)402:3<353::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeltzow TE, Xu M, Cooper DC, Hu XT, Tonegawa S, Wolf ME, et al. Alterations in dopamine release but not dopamine autoreceptor function in dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2231–2238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B. Differential distribution of D3 dopamine receptors in the brains of several mammalian species. Brain Res. 1998;800:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque D, Diaz J, Pilon C, Martres MP, Giros B, Souil E, et al. Identification, characterization, and localization of the dopamine D3 receptor in rat brain using 7-[3H]hydroxy-N,N-di-n-propyl-2-aminotetralin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8155–8159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Greve DN, Dai G, Marota JJ, Mandeville JB. Remifentanil administration reveals biphasic phMRI temporal responses in rat consistent with dynamic receptor regulation. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1042–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandeville JB, Jenkins BG, Chen YC, Choi JK, Kim YR, Belen D, et al. Exogenous contrast agent improves sensitivity of gradient-echo functional magnetic resonance imaging at 9.4 T. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1272–1281. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandeville JB, Jenkins BG, Kosofsky BE, Moskowitz MA, Rosen BR, Marota JJ. Regional sensitivity and coupling of BOLD and CBV changes during stimulation of rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:443–447. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200103)45:3<443::aid-mrm1058>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marota JJ, Mandeville JB, Weisskoff RM, Moskowitz MA, Rosen BR, Kosofsky BE. Cocaine activation discriminates dopaminergic projections by temporal response: an fMRI study in Rat. Neuroimage. 2000;11:13–23. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH. Update on dopamine receptors. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1994;6:79–90. doi: 10.3109/10401239409148986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Weber SM, Coffey GP, Joyce JN. Increases in dopamine D3 receptor binding in rats receiving a cocaine challenge at various time points after cocaine self-administration: implications for cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1479–1487. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Grundt P, Nader MA. Dopamine D3 receptor partial agonists and antagonists as potential drug abuse therapeutic agents. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3663–3679. doi: 10.1021/jm040190e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV, Brownell AL, Iris Chen YC, Livni E, Coyle JT, Rosen BR, et al. Detection of the effects of dopamine receptor supersensitivity using pharmacological MRI and correlations with PET. Synapse. 2000;36:57–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200004)36:1<57::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino LJ. Functional consequences of acute cocaine treatment depend on route of administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:343–351. doi: 10.1007/BF02244931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard LM, Logue AD, Hayes S, Welge JA, Xu M, Zhang J, et al. 7-OH-DPAT and PD 128907 selectively activate the D3 dopamine receptor in a novel environment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:100–107. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayevsky KS, Gainetdinov RR, Grekhova TV, Sotnikova TD. Regulation of dopamine release and metabolism in rat striatum in vivo: effects of dopamine receptor antagonists. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1995;19:1285–1303. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(95)00267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavill C, Taylor SG, Wood MD, Ashmeade T, Austin NE, Avenell KY, et al. Pharmacological actions of a novel, high-affinity, and selective human dopamine D(3) receptor antagonist, SB-277011-A. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:1154–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtand NM, Kelsoe JR, Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Regional quantification of D1, D2, and D3 dopamine receptor mRNA in rat brain using a ribonuclease protection assay. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;33:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger RC, Salmeron BJ, Ross TJ, Amen SL, Sanfilipo M, Hoffmann RG, et al. Neural correlates of high and craving during cocaine self-administration using BOLD fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;26:1097–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Pernaute R, Jenkins BG, Choi JK, Iris Chen YC, Isacson O. In vivo evidence of D3 dopamine receptor sensitization in parkinsonian primates and rodents with l-DOPA-induced dyskinesias. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz Y, Schmauss C, Sulzer D. Altered dopamine release and uptake kinetics in mice lacking D2 receptors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8002–8009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08002.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JC, Diaz J, Bordet R, Griffon N, Perachon S, Pilon C, et al. Functional implications of multiple dopamine receptor subtypes: the D1/D3 receptor coexistence. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz A, Gozzi A, Reese T, Bertani S, Crestan V, Hagan J, et al. Selective dopamine D(3) receptor antagonist SB-277011-A potentiates phMRI response to acute amphetamine challenge in the rat brain. Synapse. 2004;54:1–10. doi: 10.1002/syn.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz AJ, Gozzi A, Reese T, Heidbreder CA, Bifone A. Pharmacological modulation of functional connectivity: the correlation structure underlying the phMRI response to d-amphetamine modified by selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonist SB277011A. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen T, Weissleder R, Papisov M, Bogdanov A, Jr, Brady TJ. Monocrystalline iron oxide nanocompounds (MION): physicochemical properties. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:599–604. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347:146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K, Carlsson A, Waters N. Locomotor inhibition by the D3 ligand R-(+)-7-OH-DPAT is independent of changes in dopamine release. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1994;95:71–74. doi: 10.1007/BF01283032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. A direct projection from Ammon's horn to prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;217:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Todd RD, O'Malley KL. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptors inhibit dopamine release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:475–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villringer A, Rosen BR, Belliveau JW, Acerman JL, Lauffer RB, Buxton RB, et al. Dynamic imaging with lanthanidechelates in normal brain: contrast due to magnetic susceptibility effects. Magn. Reson. Med. 1988;6:164–174. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910060205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorel SR, Ashby CR, Jr, Paul M, Liu X, Hayes R, Hagan JJ, et al. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9595–9603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R, Elizondo G, Wittenberg J, Rabito CA, Bengele HH, Josephson L. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide: characterization of a new class of contrast agents for MR imaging. Radiology. 1990;175:489–493. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2326474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Gilbert J, Campos AC, Kline N, Ashby CR, Jr, Hagan JJ, et al. Blockade of mesolimbic dopamine D3 receptors inhibits stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1858-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharchuk G, Mandeville JB, Bogdanov AA, Jr, Weissleder R, Rosen BR, Marota JJ. Cerebrovascular dynamics of autoregulation and hypoperfusion. An MRI study of CBF and changes in total and microvascular cerebral blood volume during hemorrhagic hypotension. Stroke. 1999;30:2197–2204. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2197. discussion 2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Andersen A, Grondin R, Barber T, Avison R, Gerhardt G, et al. Pharmacological MRI mapping of age-associated changes in basal ganglia circuitry of awake rhesus monkeys. Neuroimage. 2001;14:1159–1167. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]