Abstract

Background Antonovsky's concept of sense of coherence (SOC) has been suggested to relate to health, especially mental health and preventive health behaviours. Psychological distress has been identified as a risk factor for pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The study of SOC and diabetes has not received much attention in Greece. This study aims to explore the extent to which type 2 diabetes mellitus can affect the SOC score.

Methods An observational design was used to test the study hypothesis that individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus would have a lower SOC than those without diabetes mellitus. A total of 202 individuals were studied, consisting of 100 people with diabetes mellitus (the study group) and 102 people with non-chronic orthopaedic conditions (the control group). All of the participants were patients of the Diabetic Clinic or the Orthopaedic Clinic of Livadia Hospital in Central Greece. SOC was assessed using a 29-item SOC questionnaire that had been translated into Greek and validated.

Results Patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus had 2.4 times higher odds of having a high SOC score than patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P = 0.036; odds ratio [OR] = 2.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06–5.23). Male patients had 3.9 times higher odds of having a high SOC score (P < 0.001; OR = 3.85, 95% CI = 1.71–8.67) than female patients. With regard to education, patients with a lower level of education had almost three times higher odds of having a high SOC score than patients with a higher level of education (P = 0.024; OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.15–7.67).

Conclusions This study adds to the existing literature and indicates that SOC is a health asset. A study with an experimental design would clarify the interesting hypothesis of this study.

Keywords: diabetes, sense of coherence, survey

Introduction

Recent studies indicate that the prevalence rates of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes have reached epidemic levels globally. The International Diabetes Foundation reported that 366 million people were living with diabetes mellitus worldwide in 2011, and that 4.6 million people died from diabetes during that same year. This figure reflects an increase of 37 million since 2007, and is projected to increase to 552 million by 2030.1 The World Health Organization has reported that deaths due to diabetes are likely to increase by 50% within the next 10 years.2

In Europe, the diabetes mellitus health burden and projections for the coming years are equally worrying. The number of people currently living with the disease is reported to be 52 million (8.4% of men and 7.8% of women in the European population), and the percentage of resulting deaths among those aged 20–79 years is reported to be 11%. Diabetes also appears to be a significant cause of premature death in middle-aged women, accounting for approximately one in seven deaths in the 50–59 years group age.3

In Greece, approximately one million people were reported to suffer from diabetes mellitus in 2009.4 Data from Greece have indicated a decrease in the age of onset of diabetes mellitus for both types of the condition, and highlight the importance of this trend among young people. These data as well as the rising projections for the coming decades indicate a severe disease burden with multiple complications, and unless action is taken it is predicted to affect all age groups of the population as well as the national health system.4 Sotiropoulos et al found that 33.4% of Greek adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus reported an increase in depressive symptoms. This figure is expected to rise in the coming year due to uncertainties introduced by the debt of the Greek financial crisis, which has an enormous impact on chronically ill patients, and particularly those of low socio-economic status.5

Certain comorbidities, such as mental health problems, increase the risk of pre-diabetes6 and type 2 diabetes mellitus.7 Also, the prevalence of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes is consistently higher for people with psychopathology.8 The growing awareness of the multiple correlations between depression and diabetes mellitus is reflected in a book published by the World Psychiatric Association in 2010.9 Moreover, patients suffering from depression together with type 2 diabetes show less compliance with lifestyle and behaviour changes recommended by physicians (e.g. adopting an appropriate diet, smoking cessation, increased physical activity) than those who have diabetes alone.10

Antonovsky, in his theory about salutogenesis, introduced the concept of sense of coherence (SOC) as an alternative approach to assessing people's health outcomes.11 The SOC is defined as ‘the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that one's environment is predictable and that things will work out as well as can reasonably be expected.’ It is considered to be a mixture of optimism and control.12 ‘The SOC theory is made up of three core components: comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness. Comprehensibility is the extent to which our internal and external environments make “cognitive sense.” Manageability is the extent to which we believe that the resources (internal or external, such as finances, social support and environmental factors) at our disposal are adequate to meet the demands of the stressor. Meaningfulness is described as the motivational element of the SOC, and relates to whether we perceive the challenge to be worthy of emotional commitment and investment.’13 In other words, salutogenesis theory, including SOC, explains why some individuals remain healthy despite encountering major stressors, while others do not.12 The stronger their SOC, the more likely a person is to be able to adopt appropriate coping strategies. Study participants who have high SOC scores are less likely to regard a particular situation as threatening or ‘out of control’, and more likely to perceive it as a challenging event and thus, by viewing it in a positive manner, to be able to maintain their good health under stressful circumstances.11 The strong relationship between SOC and perceived health (especially mental health), and its high accuracy and correlation with health outcomes as well as with preventive health behaviours, have been well documented in the literature.14–22

SOC has been investigated recently in patients with diabetes mellitus, but the available data are contradictory. In two studies that were conducted among patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, SOC did not correlate with metabolic control.23,24 Moreover, the findings of Svartvik et al supported the view that glucose tolerance was not affected by SOC.25 On the other hand, a study in patients with both types of diabetes (types 1 and 2) indicated that higher SOC scores were correlated with better glycaemic control.26 A recent study pointed out that higher SOC scores were associated with lower HbA1c values in patients with type 1 diabetes.27 Another study showed that although no direct relationship exists between SOC and treatment results, measured as HbA1c levels, the more positive the patients' perception of their health, the higher their SOC scores were, and the lower the levels of HbA1c were.28 In addition, low SOC has been reported to be a risk factor for the onset of diabetes. In prospective and cross-sectional studies, individuals with a low SOC score were found to be at higher risk of developing diabetes mellitus.29–31

Aim and objectives

Recent studies in Greece32–34 have examined SOC and its impact on health-related issues. Therefore it was of interest to explore this subject further by reporting data on a potential association between SOC and diabetes mellitus in a Greek population. This observational study reports the level of SOC in patients visiting a hospital clinic with diabetes mellitus compared with another hospital control group. Other objectives were to explore whether sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, level of education and occupation could add to this investigation. The impact of this study in the current primary healthcare settings, which are affected by the financial austerity in the healthcare system, is expected to be high.

Methods

Type of study and setting

An observational study was conducted during a 4-month period from August to November 2009 in the Diabetes and Orthopaedic Clinics in the Livadia General Hospital in Central Greece. The hospital serves a population of 100 000 people from the city of Livadia and the surrounding villages.

Study design and participants

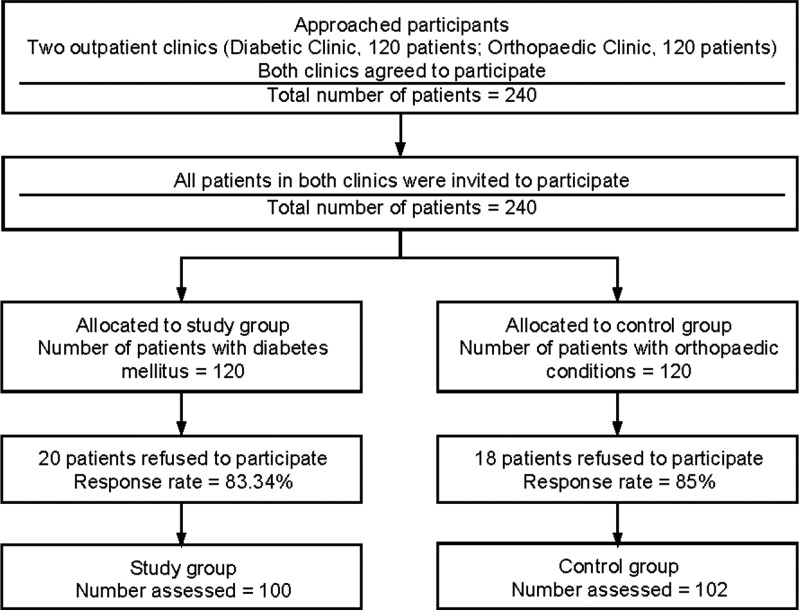

All of the participants were Greek citizens, as no other ethnicities were registered at the participating clinics during the patient recruitment period. A simple random sampling method was used to select the 202 participants allocated to the study group and the control group. Participants in the first group were selected from the Diabetic Clinic of this hospital, and had already been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. Individuals were eligible for inclusion in the study if they lived in the defined area, consented to take part in the survey, had not developed complications from diabetes mellitus, did not suffer from serious chronic health problems (myocardial infarction, chronic kidney failure, stroke and psychiatric problems), currently received medication for diabetes mellitus, and were attended regularly by a doctor of the hospital (ICD-10: E11).35 The participants in the control group were selected from the Orthopaedic Clinic and had various non-chronic orthopaedic conditions, including upper and lower limb fractures, upper and lower limb strain, and upper and lower skin injuries (ICD-10: S40–49, S50–59, S60–69, S70–79, S80–89).35 The specific group was regarded as the appropriate control group, as participants did not suffer from a chronic health problem that might have influenced SOC (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants to the study.

Measurements

In our study, the Antonovsky 29-item Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC-29), including seven questions on demographic data of the participants, was used. This scale has been translated into Greek and validated.36 The response options consisted of a 7-point scale (i.e. the possible responses ranged from 1 to 7). The questions measured all three components of the SOC scale, with 11 questions relating to comprehensibility, 10 questions relating to manageability, and 8 questions relating to meaningfulness. Items 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11, 13, 14, 16, 20, 23, 25 and 27 were reverse-scored before the total score was calculated. Information was collected at the same time from both the intervention group and the control group.

Potential source of bias

The population in this study may not be representative of the general population, as people with type 2 diabetes mellitus could also be monitored and treated privately. Therefore one factor that could have influenced participation and thus inclusion in this study is participants' socio-economic status, as patients who visit public hospital doctors tend to be of lower socio-economic status than those who visit private physicians. Furthermore, the difference in mean age between the two groups (study group: 67 years, 95% CI = 69–72 years; control group: 71 years, 95% CI = 65–68 years) may limit the external validity of this study.

Ethical approval

All of the study participants gave their written consent before completing the questionnaires, and the study was approved by the Livadia Hospital Ethics Committee.

Questionnaire structure and coding

In addition to the SOC-related questions, a small number of sociodemographic questions were included in the questionnaire, namely age and gender of respondent, level of education, marital status and employment status. The level of education was recorded according to the Greek educational system and consisted of four categories (primary, junior high school, senior high school and university/college). The above categories were merged for statistical reasons, leading to two categories (namely primary/secondary education and university/college). Marital status initially consisted of four major categories (i.e. single, divorced, widowed and married). During the process of analysis these were recoded into two categories, namely married and single/divorced/widowed. Finally, employment status was divided into two categories, namely those who were currently working and those who were not working (including pensioners and unemployed individuals).

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS 19 statistical software was used to analyse the collected data. The first step of the analyses included descriptive statistics obtained from the two groups. Subsequently, univariate analysis was performed to investigate the statistical significance of specific risk factors (SOC score, age, level of education and employment status) in people with diabetes. Independent-samples t-test and chi-square tests were used to detect differences in the risk factors within the two groups (i.e. age, gender, marital status, level of education and employment status). The SOC scale was divided into quartiles, and chi-square plus One-way-ANOVA tests were applied to detect interquartile variation within the two groups. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used for those independent variables that were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the context of a univariate analysis, in order to identify which of these were statistically significant predictors of a high SOC score.

Results

Participant characteristics

Each case (i.e. patient with diabetes) was matched to one control based on gender, marital status and place of residence. A total of 202 patients participated in the study. The mean age of participants was 71 years in the control group and 67 years in the study group (P < 0.0001).

The percentage of male respondents was higher in the control group (55% male and 45% female) than in the study group (47% male and 53% female), although this difference was not statistically significant (P < 0.259; see Table 1). With regard to the marital status of the respondents, the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant: 69 patients (68%) in the study group and 74 patients (74%) in the control group reported being married (P = 0.321). The level of education was found to differ significantly between the two groups: 23 patients (23%) with diabetes mellitus (i.e. in the study group) had a higher level of education (technical college or university), whereas only 8 respondents (8%) in the control group were in this category (P = 0.004). Another difference between the two groups was that 31 patients (30%) with type 2 diabetes mellitus (i.e. in the study group) were currently working, whereas only 7 patients (7%) in the control group were currently employed. The remaining participants in both groups were retired, unemployed or housewives. The difference in employment status between the control and study groups was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.0001), which could be related to the statistically significant difference in age that was observed.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents in the two groups

| Respondent group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 100) | Study group (n = 102) | P-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Mean age (years) | |||

| (95% CI) | 71 (69–72) | 67 (65–68) | < 0.0001* |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 45 (45) | 54 (53) | 0.259** |

| Male | 55 (55) | 48 (47) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 74 (74) | 69 (68) | 0.321† |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 26 (26) | 33 (32) | |

| Level of education | |||

| Primary/secondary school | 92 (92) | 78 (77) | 0.004‡ |

| Technical college/university | 8 (8) | 23 (23) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Not working | 93 (93) | 71 (70) | < 0.0001§ |

| Working | 7 (7) | 31 (30) | |

* Mean age was compared between groups using independent-samples t-test, the test statistic being t(2,197) = 3.826.

** The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 1.274 (df = 1).

† The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 0.986 (df = 1).

‡ The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 8.406 (df = 1).

§ The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 18.091 (df = 1).

In summary, respondents with diabetes mellitus (the study group) were found to be younger, had a higher level of education and were currently more likely to be employed than the respondents in the control group (see Table 1).

SOC in the two groups

It was observed that in the study group (patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus) the first and third quartiles had lower scores compared with the control group, while the median values were identical for both groups (121). The use of non-parametric tests indicated that the overall SOC score did not vary significantly within the two groups (P = 0.132; see Table 2).

Table 2.

SOC scale analyses: quartiles

| SOC score* | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percentiles | Control group | Study group |

| Minimum value | 70 | 54 |

| 25 | 115 | 110 |

| Median 50 | 121 | 121 |

| 75 | 145 | 138 |

| Maximum value | 176 | 179 |

* The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare SOC score with P-value = 0.132.

Quartile analyses indicated that there was no statistically significant change in the sociodemographic characteristics within patients in the control group, whereas a statistically significant difference in the sociodemographic characteristics within patients in the study group was observed (see Tables 3 and 4). Specifically, gender, level of education, marital status and employment status were all found to differ significantly (P = 0.003, 0.044, 0.047 and 0.044, respectively). The mean age of the patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus did not vary significantly across quartiles (P = 0.284).

Table 3.

Quartile analyses in the control group (patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus)

| Sense of coherence: control group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile | Q1 (n = 27) | Q2 (n = 25) | Q3 (n = 22) | Q4 (n = 23) | P-value |

| Mean age (years) | 71 | 68 | 72 | 73 | 0.143* |

| (95% CI) | (68–74) | (65–71) | (67–76) | (70–75) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 15 (56) | 12 (48) | 10 (45) | 6 (26) | 0.201** |

| Male | 12 (44) | 13 (52) | 12 (55) | 17 (74) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Widowed/divorced/single | 7 (26) | 6 (24) | 7 (32) | 5 (22) | 0.883† |

| Married | 20 (74) | 19 (76) | 15 (68) | 18 (78) | |

| Level of education, n (%) | |||||

| Primary/secondary school | 22 (82) | 23 (92) | 21 (96) | 23 (100) | 0.101‡ |

| Technical college/university | 5 (18) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||||

| Not working | 24 (89) | 23 (92) | 21 (96) | 22 (96) | 0.756§ |

| Working | 3 (11) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |

* Mean age was compared between groups using one-way ANOVA, the test statistic being F(3,92) = 1.855.

** The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 4.628 (df = 3).

†The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 0.657 (df = 3).

‡The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 6.232 (df = 3).

§The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 1.152 (df = 3).

Table 4.

Quartile analyses in the study group (patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus)

| Sense of coherence: study group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile | Q1 (n = 25) | Q2 (n = 23) | Q3 (n = 28) | Q4 (n = 19) | P-value |

| Mean age (years) | 67 | 68 | 66 | 63 | 0.284* |

| 95% CI | (63–70) | (65–71) | (62–69) | (58–67) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 18 (72) | 7 (30) | 20 (71) | 7 (37) | 0.003** |

| Male | 7 (28) | 16 (70) | 8 (29) | 12 (63) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Widowed/divorced/single | 11 (44) | 11 (48) | 6 (21) | 3 (16) | 0.047† |

| Married | 14 (56) | 12 (52) | 22 (79) | 16 (84) | |

| Level of education, n (%) | |||||

| Primary/secondary school | 14 (58) | 21 (91) | 22 (79) | 16 (84) | 0.044‡ |

| Technical college/university | 10 (42) | 2 (9) | 6 (21) | 3 (16) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||||

| Not working | 19 (76) | 16 (70) | 22 (79) | 8 (42) | 0.044§ |

| Working | 6 (24) | 7 (30) | 6 (21) | 11 (58) | |

* Mean age was compared between groups using independent-samples t-test, the test statistic being F(3,89) = 1.287.

** The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 14.094 (df = 3).

† The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 7.935 (df = 3).

‡ The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 8.118 (df = 3).

§ The chi-squared test of independence was applied: χ2 = 8.103 (df = 3).

Independent variables and correlation with the two groups

The SOC scores were divided into two categories, with scores below 110 considered to be low. From the results of Logistic Regression Model 1, it is concluded that respondents without type 2 diabetes mellitus (the control group) had 2.4 times higher odds of having a high SOC score than patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (i.e. patients in the study group) (OR = 2.35; 95% CI = 1.06–5.23). In addition, male patients had 3.9 times higher odds of having a high SOC score than female patients (OR = 3.85; 95% CI = 1.71–8.67). Age was not a statistically significant predictor of a high SOC score (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Model 1*: logistic regression predicting the odds of having a high SOC score (defined as a score of > 110) associated with the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (study/control group), gender and age

| Predictor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus (control group) | 2.35 | 1.06–5.23 | 0.036 |

| Male | 3.85 | 1.71–8.67 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.18 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.177 |

* Overall likelihood ratio: χ2 (df = 3) = 16.852, P-value = 0.001; pseudo R2 = 0.085.

According to the results of Logistic Regression Model 2, the only statistically significant predictor of a high SOC score was the level of education. Patients with a low level of education (primary or secondary education) had almost three times higher odds of having a high SOC score compared with respondents with a higher level of education (technical college or university) (OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.15–7.67). Marital status and employment status were not statistically significant predictors of a high SOC score (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Model 2*: logistic regression predicting the odds of having a high SOC score (defined as a score of > 110) associated with marital status, level of education and current employment status

| Predictor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Married | 1.88 | 0.88–4.04 | 0.106 |

| Low level of education | 2.97 | 1.15–7.67 | 0.024 |

| Currently working | 1.38 | 0.50–3.85 | 0.535 |

* Overall likelihood ratio: χ2 (df = 3) = 7.394, P-value = 0.060; pseudo R2 = 0.038.

Discussion

Main findings

The quartile limits (first and third) of SOC scores were found to be lower in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus than in those without this disorder, whereas the median SOC scores for the two groups were identical. The median SOC score seems to be consistent with the findings of other studies indicating that people with underlying diseases tend to have lower SOC scores, ranging from 100.5 points (SD 28.50) to 164.5 points (SD 17.10).14 This finding has also been confirmed by other researchers' conclusions supporting the view that SOC scores decrease in patients with chronic illnesses, which have a negative influence on their daily lives.37–40

According to our results, patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus had higher odds of having high SOC scores than those with underlying type 2 diabetes mellitus, which indicates that people with low SOC scores could be more susceptible to type 2 diabetes mellitus. The findings of this study are consistent with recent studies that reported a correlation between low SOC scores and diabetes.30,31 The present observational study cannot draw firm conclusions regarding the causality of these associations. Further research is needed to shed light in this direction.

Several studies have been performed to investigate the link between mental health and diabetes mellitus onset in healthy individuals.41–43 Although different methodologies were used, one conclusion that could be drawn is that anxiety, poor stress coping skills and depression were independent risk factors for onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kouvonen et al also investigated the relationship between SOC and diabetes mellitus.29 In a prospective occupational cohort study, it was pointed out that low SOC was associated with a higher risk of developing diabetes mellitus in employees, and it was stipulated that strengthening SOC in employees aged up to 50 years could play an important role in efforts to decrease the incidence of diabetes mellitus.29 Agardh et al reported that they reached the same conclusion, and pointed out that work-related stress and low SOC were associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in women.30 Hilding et al also pointed out that low SOC increases the risk of developing diabetes mellitus in both men and women with a family history of diabetes.31

Determinants of SOC in the light of the literature

An association between gender and SOC score was observed, with men tending to have higher scores. This finding seemed to be consistent across studies from Greece and Sweden.44,45

Contrary to theoretical expectations, our findings indicated that individuals with a lower level of education (primary or secondary) had higher odds of having a high SOC score than individuals with a higher level of education. In other studies, level of education has not been reported to correlate significantly with SOC scores. Our speculations focus on whether this finding could be interpreted as meaning that well-educated people with low SOC scores are at risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. One possible explanation could be that people with a high level of education undertake jobs that involve greater responsibility, and are exposed to work-related stress. In the literature there is an established correlation between SOC and psychosocial stress at work, particularly that due to overtime42 and effort–reward imbalance.46 In addition, it has been pointed out that work-related stress is frequently associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus.6,30 Further research studies are required to investigate the link between level of education and the onset of diabetes before valid conclusions can be drawn pertaining to its role as an independent risk factor for the development of diabetes. It would also be useful to research this field further in order to identify potential interventions that could lead to positive changes in the work environment, and help those with low SOC scores to develop more efficient stress management skills.47

Limitations

In Greece, investigation of the correlation between SOC and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus seems to have been rather neglected, and addressing this is the main contribution made by the present study. However, its results should be viewed with caution because it was an observational study that can contribute to plausible associations without offering any proof of causation. In addition, it is possible that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus may often visit private clinics, and these individuals would not therefore be included in our sample. Another weakness of the present study, which may limit the impact of the results, is the lack of investigation of the direct correlation between SOC scores and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. We consider such evidence to be of major importance, and plan to investigate this area further in order to understand more about diabetes risk factors and their interrelationship with the psychosocial mechanisms that drive the disease. Finally, age, level of education and employment status differed between the study group and the control group, and this could have an impact on the interpretation of the results. In addition, the results may have been affected by recall bias, as the study relied on self-reported information. Another limitation is that the study was conducted in a local hospital with participants who may differ from those representing the general population. This also applies to other population groups suffering from other underlying conditions. Therefore the generalisability of our findings is limited to the specific setting of our study.

Implications

The literature suggests that low SOC may be improved by certain psychological interventions.48–50 These findings could potentially form the foundation for the development of specific interventions (and preventive measures) to enhance coping skills in the three population groups of interest, namely people with diabetes, women, and people with a high level of education who are exposed to work-related stress. The role of health professionals is significant in this respect. Assessment of low SOC can perhaps identify individuals at high risk of developing diabetes mellitus, help patients with diabetes to better self-manage the disease, and reduce the incidence of diabetes mellitus complications that further reduce patient quality of life and increase healthcare expenditure. All of these could dramatically improve the prevention and prognosis of diabetes mellitus and have a significant impact in populations that are living in conditions of uncertainty, including those in Greece, a country that is experiencing a major financial crisis.

Conclusions

Patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus were more likely to have a high SOC score than patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. This study adds to the current literature and supports the concept of SOC as a health asset. Its findings may be suitable for implementation in health promotion programmes, particularly in the primary healthcare setting, with the aim of reducing the burden of chronic illnesses that have a major impact on mental health. Implementation of the study findings in larger population samples is expected to provide stronger evidence for the relationship between SOC and diabetes. Practitioners could also utilise the above findings in cases where the potential psychosocial determinants of chronic illnesses of their patients need to be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are most grateful to the patients who patiently and willingly completed the questionnaires. We also wish to thank in particular Dr E Thireos for his contribution to the concept and design of the study, and Mrs G Varouxi for assisting with data collection.

Contributor Information

K Merakou, Department of Public and Administrative Health, National School of Public Health, Athens, Greece.

A Koutsouri, General Hospital of Livadia, Terma Agiou Vlasiou, Livadia, Viotia, Greece.

E Antoniadou, Department of Public and Administrative Health, National School of Public Health, Athens, Greece.

A Barbouni, Department of Public and Administrative Health, National School of Public Health, Athens, Greece.

A Bertsias, Clinic of Social and Family Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

G Karageorgos, General Hospital of New Ionia ‘Agia Olga’, Athens, Greece.

C Lionis, Clinic of Social and Family Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, Brussels, Diabetes Programme, World Health Organization. www.who.int/diabetes/en/index.html (accessed August 2011).

- 2.World Health Organization Genetics and Diabetes. www.who.int/genomics/about/Diabetis-fin.pdf (accessed August 2011).

- 3.Roglic G, Unwin N. Mortality attributable to diabetes: estimates for the year 2010. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2010;87:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andriciuc C. Country Report for Greece. www.idf.org/webdata/docs/idf-europe/Country%20report%20GR%20pub.pdf (accessed August 2011).

- 5.Sotiropoulos A, Papazafiropoulou A, Apostolou O, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among non-insulin-treated Greek type 2 diabetic subjects. BMC Research Notes 2008;1:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson AK, Ekbom A, Granath F, et al. Psychological distress and risk of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes in a prospective study of Swedish middle-aged men and women. Diabetic Medicine 2008;25:834–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savill P. Identifying patients at risk of type 2 diabetes. The Practitioner 2012;256:25–7, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atlantis E. Excess burden of type 1 and type 2 diabetes due to psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders 2012;142 (Suppl.):S36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katon W, Maj M, Sartorius N. Depression and Diabetes. John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2154–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonovsky A. Health, Stress and Coping. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonovsky A. Unravelling the Mystery of Health. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson G, Hall Moran V, Axelin A, et al. Integrating a sense of coherence into the neonatal environment. BMC Pediatrics 2013;13:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2006;60:376–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Söderhamn O, Holmgren L. Testing Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale (SOC) among Swedish physically active older people. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2004;45:215–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wainwright NW, Surtees PG, Welch AA. Healthy lifestyle choices: could sense of coherence aid health promotion? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2007;61:871–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers V, Drory Y, Gerber Y. Sense of coherence predicts post-myocardial infarction trajectory of leisure time physical activity: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suraj S, Singh A. Study of sense of coherence health promoting behavior in north Indian students. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2011;134:645–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindmark U, Stegmayr B, Nilsson B, et al. Food selection associated with sense of coherence in adults. Nutrition Journal 2005;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernabe E, Kivimaki M, Tsakos G. The relationship among sense of coherence, socio-economic status, and oral health-related behaviours among Finnish dentate adults. European Journal of Oral Sciences 2009;117:413–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuner B, Miller P, Maulhardt A. Hazardous alcohol consumption and sense of coherence in emergency department patients with minor trauma. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2006;82:143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuuppelomaki M, Utriainen P. A 3-year follow-up study of health care students' sense of coherence and related smoking, drinking and physical exercise factors. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2003;40:383–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundman B, Norberg A. The significance of a sense of coherence for subjective health in persons with insulin-dependent diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1993;18:381–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson A, Adner N, Nordström G. Persons with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: acceptance and coping ability. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001;33:758–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svartvik L, Lidfeldt J, Nerbrand C, et al. Dyslipidaemia and impaired well-being in middle-aged women reporting low sense of coherence. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 2000;18:177–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen M, Kanter Y. Relation between sense of coherence and glycemic control in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Behavioral Medicine 2004;29:175–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahola AJ, Saraheimo M, Forsblom C, et al. The cross-sectional associations between sense of coherence and diabetic microvascular complications, glycaemic control, and patients' conceptions of type 1 diabetes. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010;8:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanden-Eriksson B. Coping with type-2 diabetes: the role of sense of coherence compared with active management. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2000;31:1393–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kouvonen AM, Vaanamen A, Woods SA. Sense of coherence and diabetes: a prospective occupational cohort study. BMC Public Health 2008;8:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agardh EE, Ahilbom A, Andersson T, et al. Work stress and low sense of coherence is associated with type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Swedish women. Diabetes Care 2003;26:719–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilding A, Eriksson AK, Agardh EE. The impact of family history of diabetes and lifestyle factors on abnormal glucose regulation in middle-aged Swedish men and women. Diabetologia 2006;49:2589–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lionis C, Anyfantakis D, Symvoulakis E, et al. Biopsychosocial determinants of cardiovascular disease in a rural population on Crete, Greece: formulating a hypothesis and designing the SPILI-III study. BMC Research Notes 2010;3:258, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyphantis T, Palieraki K, Voulgari PV. Coping with health-stressors and defence styles associated with health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2011;20:893–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giotakos O. Suicidal ideation, substance use, and sense of coherence in Greek male conscripts. Military Medicine 2003;168:447–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashley J. The International Classification of Diseases: the structure and content of the tenth revision. Health Trends 1990;22:135–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karalis I, Langius A, Tsirogianni M, et al. The translation-validation of the sense of coherence scale into Greek and its use in primary health care. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 2004;21:195–203 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergman E, Malm D, Berterö C, et al. Does one's sense of coherence change after an acute myocardial infarction? A two-year longitudinal study in Sweden. Nursing and Health Sciences 2011;13:156–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundman B, Forsberg KA, Jonsen E. Sense of coherence (SOC) related to health and mortality among the very old: the Umeå 85+ study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2010;51:329–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gauffin H, Landtblom AM, Raty L. Self-esteem and sense of coherence in young people with uncomplicated epilepsy: a 5-year follow-up. Epilepsy and Behavior 2010;17:520–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motzer SA, Hertig V, Jarrett M, et al. Sense of coherence and quality of life in women with and without irritable bowel syndrome. Nursing Research 2003;52:329–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egnum A. The role of depression and anxiety in onset of diabetes in a large population-based study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2007;62:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. Journal of the American Medical Association 2008;299:2751–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sairenchi T, Haruyama Y, Ishikawa Y, et al. Sense of coherence as a predictor of onset of depression among Japanese workers: a cohort study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faresjo T, Karalis I, Prinsback E, et al. Sense of coherence in Crete and Sweden: key findings and messages from a comparative study. European Journal of General Practice 2009;15:95–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindmark U, Stenstrom U, Gerdin EW, et al. The distribution of “sense of coherence” among Swedish adults: a quantitative cross-sectional population study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2010;38:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumari M, Head J, Marmot M. Prospective study of social and other risk factors for incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Whitehall II study. Archives of Internal Medicine 2004;164:1873–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heraclides A, Chandola T, Witte DR, et al. Psychosocial stress at work doubles the risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged women. Diabetes Care 2009;32:2230–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiesmann U, Rolker S, IIg H. On the stability and modifiability of the sense of coherence in active seniors [article in German]. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie 2006;39:90–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delbar V, Benor DE. Impact of a nursing intervention on cancer patients' ability to cope. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 2001;19:57–75 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langeland E, Riise T, Hanestad BR, et al. The effect of salutogenic treatment principles on coping with mental health problems. A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling 2006;62:212–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.