Abstract

Connexin 43 (Cx43) is present at the sarcolemma and the inner membrane of cardiomyocyte subsarcolemmal mitochondria (SSM). Lack or inhibition of mitochondrial Cx43 is associated with reduced mitochondrial potassium influx, which might affect mitochondrial respiration. Therefore, we analysed the importance of mitochondrial Cx43 for oxygen consumption. Acute inhibition of Cx43 in rat left ventricular (LV) SSM by 18α glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) or Cx43 mimetic peptides (Cx43-MP) reduced ADP-stimulated complex I respiration and ATP generation. Chronic reduction of Cx43 in conditional knockout mice (Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT, 5–10% of Cx43 protein compared with control Cx43fl/fl mitochondria) reduced ADP-stimulated complex I respiration of LV SSM to 47.8 ± 2.4 nmol O2/min.*mg protein (n = 8) from 61.9 ± 7.4 nmol O2/min.*mg protein in Cx43fl/fl mitochondria (n = 10, P < 0.05), while complex II respiration remained unchanged. The LV complex I activities (% of citrate synthase activity) of Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl+4-OHT mice (16.1 ± 0.9%, n = 9) were lower than in Cx43fl/fl mice (19.8 ± 1.3%, n = 8, P < 0.05); complex II activities were similar between genotypes. Supporting the importance of Cx43 for respiration, in Cx43-overexpressing HL-1 cardiomyocytes complex I respiration was increased, whereas complex II respiration remained unaffected. Taken together, mitochondrial Cx43 is required for optimal complex I activity and respiration and thus mitochondrial ATP-production.

Keywords: Connexin 43, 18α glycyrrhetinic acid, mitochondria, respiration

Introduction

The transmembrane protein Cx43 is constitutive for the formation of gap junctions between cardiomyocytes and thus essential for cell–cell communication. Connexin 43 is also present at the inner membrane of cardiomyocyte SSM, but not in cardiomyocyte interfibrillar mitochondria (IFM) [[1],[2],,[3]]. The cardioprotection by ischaemic pre-conditioning or pharmacological pre-conditioning with diazoxide, an opener of mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels (mito KATP-channels) [4], depends on the presence of Cx43 [5,6,7,8]. In murine mitochondria in which Cx43 was replaced by connexin 32 (which forms hemichannels with lower potassium conductance than Cx43 [9]), mitochondrial potassium influx is reduced [10]. Potassium uptake of mitochondria from wild-type mice is also decreased by the gap junction blocker 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (18αGA) [10]. As mitochondrial potassium flux is involved in respiratory control of mitochondria [11,12], we now investigated the role of Cx43 for mitochondrial oxygen consumption and respiratory chain complex activities by its inhibition, reduction, or overexpression, respectively.

Materials and methods

Animal model

The present study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the state Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany. It conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

A conditional knockout of Cx43 was achieved by intraperitoneal injection of 3 mg 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) once per day on five consecutive days in Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl mice. Untreated Cx43fl/fl and 4-OHT-treated (Cx43fl/fl + 4-OHT) mice served as controls. The mice were 10- to 16-weeks old and sacrificed on day 11 after the first injection. The right ventricles were used to control the reduction of Cx43 by Western blot analysis. The decreased amount of Cx43 in total right ventricular protein extracts is paralleled by a reduction in mitochondrial Cx43 [1]. Left ventricles (LV) were used for the isolation of mitochondria. Lewis rats (250–350 g) were anaesthetized with enflurane, the hearts were removed, and the LV were used for isolation of mitochondria.

Overexpression of Cx43 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes

HL-1 cells, a cell line derived from mouse atrial cardiomyocytes, were cultured under 5% CO2 atmosphere in Claycomb Medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS, USA), 4 mmol/l l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 μmol/l norepinephrine, and were plated in culture flasks pre-coated with 25 μg/ml fibronectin/0.02% gelatin solution. To obtain HL-1 cells overexpressing Cx43, the coding sequence of rat Cx43 was inserted into a pBABEpuro retroviral plasmid under the control of the retroviral promoter (pBABEpuro-Cx43). Empty vector was used as control. To produce retroviral particles with the VSV-G virus envelope, which do not require any specific receptor in the target cells, the 293GPG packing cell line was transfected. After 48 hrs, supernatant rich in viral particles was collected and added to HL-1 cells. HL-1 cardiomyocytes were allowed to grow for additional 48 hrs before starting the selection with puromycin at 2 μg/ml (P8833; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Loius, MO, USA). Overexpression of Cx43 was confirmed by Western blot analysis on isolated mitochondria.

Western Blot analysis

Right ventricular tissue samples were lysed in 1× Cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA containing in mmol/l): Tris 20, NaCl 150, EDTA 1, EGTA 1, sodium pyrophosphate 2.5, β-glycerolphosphate 1, Na3VO4 1, PMSF 1, 1 μg/ml Leupeptin, 1% Triton X-100, pH7.5, supplemented with Complete Protease Inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Thirty μg proteins were electrophoretically separated on 10% SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-rat Cx43 antibodies (Zymed, Berlin, Germany), mouse monoclonal anti-rabbit glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase antibodies (GAPDH, Hytest, Turku, Finland). After incubation with the respective secondary antibodies, immunoreactive signals were detected by chemiluminescence (LumiGlo, Cell Signaling) and quantified with the Scion Image software (Frederick, MD, USA).

HL-1 cardiomyocytes were harvested using trypsin (0.05%, 25300-062; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and resuspended in isolation buffer [in mmol/l: sucrose 250, MOPS 6 pH 7.2, EGTA 1, protease inhibitors (PMSF 1, NaF 5, Na3VO4 1, protease cocktail from Sigma-Aldrich P8340)]. After centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min., mitochondria were pelleted at 8000 × g. The pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer containing 19% percoll and centrifuged at 10,000 × g. Mitochondria were diluted in Laemmli buffer, and proteins were electrophoretically separated using the same procedure described above. The purity of the mitochondrial preparation was assessed using mouse monoclonal anti-human succinate-ubiquinol oxidoreductase (complex II; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-rabbit Na/K+-ATPase (Upstate, Waltham, MA, USA).

Isolation of mitochondria

Subsarcolemmal mitochondria were isolated from tissue samples of mouse and rat LV by differential centrifugation as described previously [1].

For isolation of both SSM and IFM, rat LV tissue was processed as already described [3].

To isolate mitochondria from HL-1 cardiomyocytes, cells were harvested using trypsin (0.05%) and resuspended in isolation buffer (in mmol/l: sucrose 250, MOPS 6 pH 7.2, EGTA 1, 0.5% BSA). After centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min., mitochondria were pelleted at 8000 × g for 5 min., resuspended in isolation buffer and immediately used for measurement of respiration.

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption

Mitochondrial respiration of mouse or rat LV SSM was measured with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Oxygen meter 782, Strathkelvin, Glasgow, UK) at 25°C in incubation buffer (containing in mmol/l: 125 KCl, 10 Tris-MOPS, 1.2 Pi-Tris, 1.2 MgCl2, 0.02 EGTA-Tris, pH 7.4) as described previously [13]. Five mmol/l glutamate and 2.5 mmol/l malate were used as substrates for complex I, whereas complex II-mediated respiration was measured in the presence of 2 μmol/l rotenone (inhibits complex I) and 5 mmol/l succinate.

Oxygen consumption was determined for 100 μg LV mouse SSM or rat SSM incubated for 30 min. at 4°C in isolation buffer, without or with 250 μmol/l Cx43-mimetic peptides (SRPTEKTIFII) or Cx40-mimetic peptides (SRPTEKNVFIV). This concentration of mimetic peptides (MP) has been demonstrated to block Cx43-formed hemichannels [14]. Cx40-MP was chosen as control, since the amino acids are similar to that of the Cx43-MP and Cx40 is present in atrial but not in ventricular mitochondria [15]. After recording of basal oxygen consumption, respiration was stimulated by the addition of 40 μmol/l ADP.

One-hundred micrograms rat LV SSM proteins were added to incubation buffer supplemented with 200 μmol/l ADP. One μmol/l, then either 10 μmol/l 18αGA, which inhibits gap junctional cell communication, or the respective volume of DMSO as vehicle was added after 5 min., and the ADP-stimulated respiration was recorded for further 5 min. Oxygen consumption was quantified 1 min. before and 1 min. after addition of 18αGA or DMSO, respectively. Mitochondrial respiration was calculated as the oxygen consumption in nmol O2/min.*mg protein.

In HL-1 cardiomyocytes, complex I-mediated respiration was measured at 25°C using intact cells (200,000–250,000 cells/ml) resuspended in cell-assay buffer (in mmol/l: NaCl 140, KCl 3.6, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 2, HEPES 20 pH 7.4, glucose 5 mmol/l). Oxygen consumption was expressed as nmol O2/min.*106 cells. Complex II-mediated respiration was measured in isolated mitochondria at 25°C in incubation buffer, using rotenone and succinate as substrate, as described for mouse and rat mitochondria.

Mitochondrial membrane potential and autofluorescence

The membrane potential of 0.5 mg/ml rat LV SSM was measured at 25°C in incubation buffer with 10 nM of the potentiometric dye rhodamine 123 (Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer, Varian, Mulgrave, Australia, excitation: 503 nm; emission: 535 nm). After the membrane potential was stable, 18αGA (1, 10, 100 μmol/l) or DMSO as vehicle was added. The effect of DMSO or 18αGA on mitochondrial membrane potential was quantified by calculating the difference between the rhodamine 123 fluorescence 1 min. before and 1 min. after addition of DMSO (n = 5) or 18αGA (1 μmol/l: n = 7, 10 μmol/l: n = 6, 100 μmol/l: n = 7), respectively.

The effect of DMSO or 18αGA on mitochondrial NAD(P)H autofluorescence (excitation 340 nm, emission 460 nm) was quantified by calculating the difference between the fluorescence intensity 1 min. prior and 1 min. after addition of DMSO (n = 5) or 18αGA (1 μmol/l: n = 7, 10 μmol/l: n = 6, 100 μmol/l: n = 7), respectively.

Mitochondrial ATP generation

Fifty μg rat LV SSM were diluted in 100 μl incubation buffer supplemented with 5 mmol/l glutamate and 2.5 mmol/l malate as substrates for complex I and 0.1 mmol/l di-adenosine-pentaphosphate. Considering the lack of effect of Cx43-MP on complex II respiration, ATP generation was measured using substrates for complex I only. One-hundred microlitres of the ATP bioluminescent assay kit (1:5 diluted with incubation buffer; Sigma-Aldrich) was added and the bioluminescence was recorded for 1 min. with a Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer (Varian) at room temperature. ATP generation was initiated by the addition of 500 mmol/l ADP, and the bioluminescence was recorded for another minute. The bioluminescence of a sample without mitochondria was subtracted. Rat LV SSM were studied under control conditions (untreated) or after incubation for 30 min. at 4°C with 250 μmol/l Cx43-MP (n = 15). In addition, ATP generation was measured in the presence of 1 μmol/l 18αGA or DMSO as vehicle (n = 4). Twenty-five μg/ml oligomycin was used to inhibit the ATP synthase and to prevent ATP generation.

Activity of respiratory chain complexes

The LV of Cx43fl/fl (n = 8) and Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT mice (n = 9) were homogenized in a solution containing 50 mmol/l Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mmol/l potassium chloride, 5 mmol/l MgCl2, and 1 mmol/l ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Enzyme activities were spectrophotometrically monitored at 30°C (DU 640 photometer; Beckmann Instruments, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and normalized to citrate synthase activity. The analysis of the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I, complex II and citrate synthase as mitochondrial marker enzyme was performed as described previously [16].

Statistics

Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Oxygen consumption in HL-1 cells, basal respiration with 10 μM 18αGA, and activities of respiratory complexes were compared using unpaired Student's t-test. Western blot data for Cx43, mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial autofluorescence were compared by one-way anova and Fisher's least-significant difference tests were used for post-hoc comparisons. Oxygen consumption without or with ADP-stimulation and without or with 1 μmol/l 18αGA or mimetic peptides, respectively, was compared by two-way anova with repeated measures followed by Bonferroni tests. A P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Oxygen consumption of rat LV SSM was measured under basal conditions before and after addition of 1 μmol/l of the Cx43-hemichannel inhibitor 18αGA or DMSO as vehicle. Basal respiration (complexes I and II) of rat LV SSM was not altered by 18αGA (Fig. 1C), whereas ADP-stimulated complex I, but not complex II respiration, was reduced by 1 μmol/l 18αGA (Fig. 1D). Higher concentrations of 18αGA had toxic effects on mitochondria, as basal respiration was uncoupled by 10 μmol/l 18αGA [in nmol O2/mg*min.; complex I: 18.2 ± 1.3 before versus 22.3 ± 1.6 after (n = 6, P < 0.05); complex II: 47.8 ± 2.6 before versus 69.2 ± 4.2 after (n = 6, P < 0.05)], and NAD(P)H autofluorescence was decreased (Fig. 1B). One-hundred μmol/l 18GA decreased both membrane potential and autofluorescence (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig 1.

Effect of acute Cx43-inhibition using 18αGA on mitochondrial function. (A) Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using rhodamine 123, and the difference in mitochondrial rhodamine 123 fluorescence 1 min. before and 1 min. after addition of 18αGA (1 μmol/l: n = 7, 10 μmol/l: n = 6, 100 μmol/l: n = 7) or DMSO (n = 5), respectively, was calculated. An enhanced difference in fluorescence values indicates loss of membrane potential. *P < 0.05 versus DMSO. (B) Quantification of the difference between mitochondrial NAD(P)H autofluorescence 1 min. before and 1 min. after addition of 18αGA (1 μmol/l: n = 7, 10 μmol/l: n = 6, 100 μmol/l: n = 7) or DMSO (n = 5), respectively. An enhanced difference in fluorescence values indicates loss of NAD(P)H autofluorescence. *P < 0.05 versus DMSO. Basal (C, n = 6) and ADP-stimulated respiration (D, n = 13) were measured in rat LV SSM using substrates for complexes 1 or 2, respectively, before and after addition of 1 μmol/l 18αGA or DMSO as vehicle, respectively. *P < 0.05 versus before 18αGA.

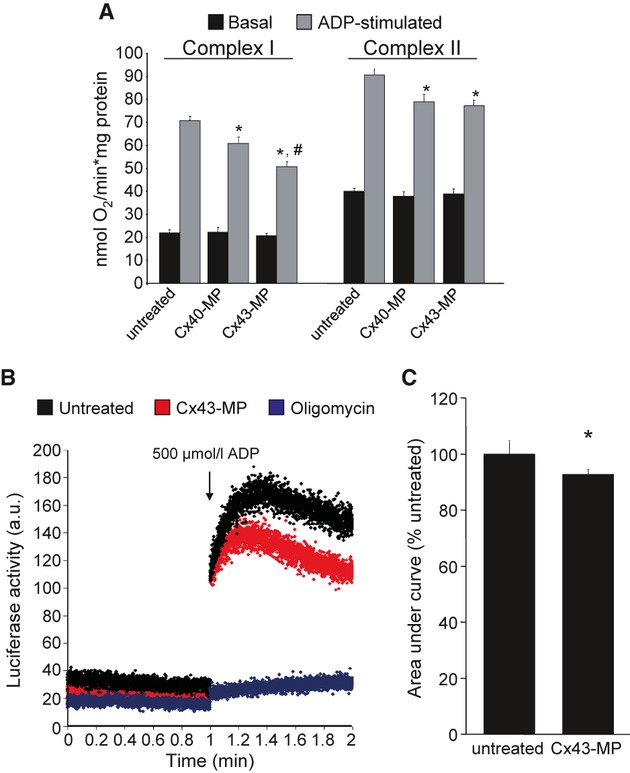

Rat LV SSM were incubated with Cx43-mimetic peptides (Cx43-MP), which are known to block Cx43-hemichannels [14]. Cx43-MP reduced ADP-stimulated complex I, but not complex II respiration, compared with control Cx40-MP peptides (Fig. 2A). Basal respiration was similar between groups. Cx43-MP did not reduce ADP-stimulated complex I respiration in IFM, which do not contain Cx43 compared with Cx40-MP (in nmol O2/mg*min., basal respiration: untreated: 17.0 ± 2.0; Cx40-MP: 19.3 ± 1.7; Cx43-MP: 20.3 ± 1.7; ADP-stimulated respiration: untreated: 74.9 ± 6.1; Cx40-MP: 58.1 ± 4.5; Cx43-MP: 58.6 ± 4.8, n = 8, P = ns Cx40-MP versus Cx43-MP). To exclude unspecific effects of Cx43-MP, ADP-stimulated complex I respiration was measured in LV SSM from conditional Cx43-knockout mice. Here, Cx43-MP also had no effect on ADP-stimulated complex I respiration (Cx43fl/fl: 34.2 ± 2.4 nmol O2/mg*min., n = 8 versus Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT: 33.5 ± 1.9 nmol O2/mg*min., n = 14, P = ns).

Fig 2.

Effect of connexin mimetic peptides on mitochondrial oxygen consumption and ATP production. (A) Basal and ADP-stimulated respiration using substrates for complex I or complex II, respectively, were measured in untreated rat LV SSM (n = 12), or SSM incubated with 250 μmol/l Cx40- (n = 12) or Cx43-MP (n = 12), respectively. *P < 0.05 versus untreated, #P < 0.05 versus Cx40-MP. (B) Original traces demonstrating luciferase activities of isolated rat SSM before and after addition of 500 μmol/l ADP under control conditions (untreated) and with Cx43 inhibition by 250 μmol/l Cx43-MP. Oligomycin, which inhibits the ATP synthase, was used as negative control. (C) ATP generation was quantified as the area under the curve for the first minute after addition of ADP in untreated or Cx43-MP-treated rat SSM (n = 15), *P < 0.05.

ATP generation of rat LV SSM treated with 250 μmol/l Cx43-MP was reduced to 92.7 ± 1.9% of untreated mitochondria (n = 15, Fig. 2B and C). In the presence of oligomycin, which inhibits the mitochondrial ATP synthase, almost no ATP was produced (Fig. 2B).

4-OHT reduced the Cx43 content to about 10% in Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl mice, but did not influence Cx43 expression in Cx43fl/fl mice (Fig. 3A and B). ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption with substrates for complexes I or II (Fig. 3C and D) was unaffected by 4-OHT in Cx43fl/fl mice, but ADP-stimulated complex I respiration was lower in Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT than in Cx43fl/fl SSM; ADP-stimulated complex II respiration was comparable between groups. Basal respiration (complexes I and II) was not modified by Cx43-deficiency (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig 3.

Effect of chronic Cx43-inhibition on oxygen consumption. (A) Western blot analysis was performed for Cx43 and GAPDH on right ventricular proteins of control mice (Cx43fl/fl), control mice treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Cx43fl/fl + 4-OHT), and conditional Cx43-knockout mice (Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT), respectively. (B) Quantification of the Cx43 expression normalized to that of GAPDH. *P < 0.05 versus Cx43fl/fl. Basal and ADP-stimulated respiration were measured using substrates for complex I (C) or complex II (D), respectively, on LV SSM of Cx43fl/fl, Cx43fl/fl + 4-OHT and Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT mice, respectively. *P < 0.05 versus Cx43fl/fl.

Activities of complex I and complex II were measured in percentage of citrate synthase activity in LV protein extracts of Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT and Cx43fl/fl mice. Complex I activity was significantly lower in the Cx43-deficient mice than in the control mice (Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT: 16.1 ± 0.9%, n = 9, versus Cx43fl/fl: 19.8 ± 1.3%, n = 8, P < 0.05). In contrast, Cx43-deficiency had no influence on complex II activity (Cx43Cre-ER(T)/fl + 4-OHT: 53.7 ± 3.5%, n = 9, versus Cx43fl/fl: 51.7 ± 3.9%, n = 8, P = ns).

Cx43 overexpressing HL-1 cardiomyocytes had a 5.0 ± 0.7 fold increase in the mitochondrial Cx43 content (n = 5, Fig. 4A). Oxygen consumption was measured in intact cells (complex I respiration) or isolated mitochondria (complex II) from Cx43-overexpressing or control-transfected HL-1 cells. Complex I respiration was increased in Cx43-overexpressing HL-1 cells, whereas complex II respiration was not affected (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Cx43-overexpression in mitochondria. (A) Western blot analysis was performed for Cx43 and the 70 kD subunit of complex II (CII) as mitochondrial marker protein on mitochondria isolated from HL-1 cells, which were transfected with the empty vector pBabe-puro or the Cx43-overexpressing vector pBabe-Cx43, respectively (n = 5). (B) Oxygen consumption was measured using substrates for complex I (cells in suspension, left panel) or substrates for complex II (isolated mitochondria, right panel) from HL-1 cells transfected with the empty vector pBabe-puro or the Cx43 overexpressing vector pBabe-Cx43, respectively. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that mitochondrial Cx43 impacts on ADP-stimulated complex I respiration and ATP production.

The effects of Cx43 overexpression as well as acute and chronic Cx43 inhibition/reduction on mitochondrial oxygen consumption were investigated. In isolated mitochondria from HL-1 cells, complex I respiration was below the detection level and was therefore measured in intact cells only. Here, overexpression of Cx43 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes increased complex I respiration compared with control-transfected cells. Cx43 overexpression had no effect on complex II respiration. As glucose, which was used as substrate in the experiments with intact cells, does not exclusively activate complex I, it is not possible to attribute the effects of Cx43-overexpression to enhanced activity of this complex only. However, the finding that Cx43-overexpression had no impact on complex II respiration in isolated mitochondria supports the role of mitochondrial Cx43 for complex I-driven oxygen consumption.

In isolated rat SSM, 1 μmol/l 18αGA, a concentration without toxic effects, reduced ADP-stimulated complex I, but not complex II respiration; higher concentrations of 18αGA (10 and 100 μmol/l) damaged mitochondria by inducing loss of membrane potential and NAD(P)H autofluorescence and by uncoupling basal respiration. Ten μmol/l of the 18αGA isomer 18βGA has previously been reported to induce mitochondrial transition pore opening in rat heart mitochondria [17].

The effects of 18αGA were more pronounced than those measured with Cx43-MP. Apart from blocking Cx43-mediated effects, 18αGA may react directly with a subunit of complex I [17], explaining its greater potency.

Cx43-MP block Cx43-formed hemichannels and gap junctions [14]. While Cx40 and Cx43 are both expressed in endothelial cells, only Cx43 is present in ventricular cardiomyocytes and in isolated ventricular mitochondria [15]. Cx40 is present in atrial cardiomyocytes and was detected in atrial mitochondria as well [15]. Thus, any effect observed with Cx40-MP served as control for non-cardiomyocyte mitochondria isolated from LV myocardium, and indeed, the Cx40-MP decreased mitochondrial respiration slightly. While the localization of Cx40 in mitochondria from endothelial cells has not been demonstrated yet, the putative presence of Cx40 in these organelles may be responsible for the reduced oxygen consumption induced by Cx40-MP. Importantly, the reduction of complex I respiration, but not complex II respiration, by Cx43-MP was significantly greater than by Cx40-MP in SSM (containing Cx43) but not IFM (lacking Cx43), highlighting the specificity of the observed effect.

To investigate the effect of a more chronic Cx43 reduction on respiration, we studied the oxygen consumption of mitochondria from conditional Cx43-knockout mice and found reduced ADP-stimulated complex I respiration. It is possible that Cx43-deficiency affects the composition and hence activity of complex I, as the Cx43-carboxyterminus has also been detected in cardiomyocyte nuclei [18] and Cx43-deficient hearts have decreased transcript levels of 11 nuclear genes encoding subunits of complex I, whereas mRNAs encoding complex II subunits are not differentially expressed [19]. Of note, specifically complex I activity was reduced in Cx43-knockout mice. However, as not only chronic reduction but also acute inhibition of Cx43 reduced complex I respiration, Cx43 may directly affect complex I by interfering with complex I subunits. However, co-immunoprecipitation studies did not detect an interaction of subunits of complex I with Cx43 (data not shown).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the importance of mitochondrial Cx43 for oxygen consumption and ATP production. Inhibition or reduction of mitochondrial Cx43 specifically decreases complex I respiration.

Acknowledgments

R.S. was the recipient of a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Schu 843/7-2). This study was partially supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación de España, SAF08-03736/FIS09-02034.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boengler K, Dodoni G, Rodriguez-Sinovas A, et al. Connexin 43 in cardiomyocyte mitochondria and its increase by ischemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:234–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Sinovas A, Boengler K, Cabestrero A, et al. Translocation of connexin 43 to the inner mitochondrial membrane of cardiomyocytes through the heat shock protein 90-dependent TOM pathway and its importance for cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2006;99:93–101. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000230315.56904.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boengler K, Stahlhofen S, van de Sand A, et al. Presence of connexin 43 in subsarcolemmal, but not in interfibrillar cardiomyocyte mitochondria. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:141–7. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusch G, Boengler K, Schulz R. Cardioprotection: nitric oxide, protein kinases, and mitochondria. Circulation. 2008;118:1915–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanke U, Konietzka I, Duschin A, et al. No ischemic preconditioning in heterozygous connexin43-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1740–2. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00442.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Heinzel FR, Boengler K, et al. Role of connexin 43 in ischemic preconditioning does not involve intercellular communication through gap junctions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:161–3. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel FR, Luo Y, Li X, et al. Impairment of diazoxide-induced formation of reactive oxygen species and loss of cardioprotection in connexin 43 deficient mice. Circ Res. 2005;97:583–6. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000181171.65293.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottlaender D, Boengler K, Wolny M, et al. Connexin 43 acts as a cytoprotective mediator of signal transduction by stimulating mitochondrial KATP channels in mouse cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1441–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI40927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Harris AL. Voltage-sensing and substate rectification: moving parts of connexin channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:165–9. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miro-Casas E, Ruiz-Meana M, Agullo E, et al. Connexin43 in cardiomyocyte mitochondria contributes to mitochondrial potassium uptake. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:747–56. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korge P, Honda HM, Weiss JN. K+-dependent regulation of matrix volume improves mitochondrial function under conditions mimicking ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H66–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01296.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen A, Camara AK, Aldakkak M, et al. Mitochondrial Ca2 + -induced K+ influx increases respiration and enhances ROS production while maintaining membrane potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C148–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00215.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boengler K, Gres P, Dodoni G, et al. Mitochondrial respiration and membrane potential after low-flow ischemia are not affected by ischemic preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:610–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Mager A, et al. ATP release from activated neutrophils occurs via connexin 43 and modulates adenosine-dependent endothelial cell function. Circ Res. 2006;99:1100–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250174.31269.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Boengler K, Totzeck A, et al. Connexin 43 in ischemic pre- and postconditioning. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12:261–6. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheubel RJ, Tostlebe M, Simm A, et al. Dysfunctoin of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I in human failing myocardium is not due to disturbed mitochondrial gene expression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2174–81. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia V, Brunati AM, Fiore C, et al. Glycyrrhetinic acid as inhibitor or amplifier of permeability transition in rat heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:313–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang X, Doble BW, Kardami E. The carboxy-tail of connexin-43 localizes to the nucleus and inhibits cell growth. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Li W, et al. Genes controlling multiple functional pathways are transcriptionally regulated in connexin43 null mouse heart. Physiol Genomics. 2005;20:211–23. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00229.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]