Abstract

Patients with end-stage kidney disease on peritoneal dialysis often develop progressive scarring of the peritoneal tissues. This manifests as submesothelial thickening and is associated with increased vascularization that leads to ultrafiltration dysfunction. Hypoxia induces a characteristic series of responses including angiogenesis and fibrosis. We investigated the role of hypoxia in peritoneal membrane damage. An adenovirus expressing transforming growth factor (TGF) β was used to induce peritoneal fibrosis. We evaluated the effect of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, which has been previously shown to block hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α. We also assessed the effect of HIF1α independently using an adenovirus expressing active HIF1α. To identify the TGFβ1-independent effects of HIF1α, we expressed HIF1α in the peritoneum of mice lacking the TGFβ signalling molecule Smad3. We demonstrate that TGFβ-induced fibroproliferative tissue is hypoxic. Rapamycin did not affect the early angiogenic response, but inhibited angiogenesis and submesothelial thickening 21 days after induction of fibrosis. In primary mesothelial cell culture, rapamycin had no effect on TGFβ-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) but did suppress hypoxia-induced VEGF. HIF1α induced submesothelial thickening and angiogenesis in peritoneal tissue. The fibrogenic effects of HIF1α were Smad3 dependent. In summary, submesothelial hypoxia may be an important secondary factor, which augments TGFβ-induced peritoneal injury. The hypoxic response is mediated partly through HIF1α and the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin blocks the hypoxic-induced angiogenic effects but does not affect the direct TGFβ-mediated fibrosis and angiogenesis.

Keywords: hypoxia-inducible factor, transforming growth factor, adenovirus, Smad, mTOR, rapamycin, vascular endothelial growth factor, angiogenesis

Introduction

The peritoneal membrane provides life support for patients who rely on peritoneal dialysis (PD) as their renal replacement therapy. The removal of salt and water by ultrafiltration (UF) depends on the maintenance of a small solute gradient between the hypertonic dialysate and the intravascular space. Over time, most PD patients develop increased solute transport across the peritoneal membrane with a concomitant decrease in UF secondary to a rapid loss of the osmotic gradient [1]. This fast peritoneal solute transport status and UF dysfunction are associated with fibrosis and angiogenesis of the peritoneal tissues [2]. Increased peritoneal membrane solute transport is associated with increased mortality in patients on PD therapy [3]. Peritoneal fibrosis has been associated with the non-physiological nature of PD solutions [4], uraemia [5] and recurrent infections [6].

Transforming growth factor (TGF) β is involved in the wound healing response and is essential in progressive changes in the peritoneal membrane over time. Several studies have demonstrated an association between peritoneal effluent TGFβ concentration and peritoneal membrane injury in patients on PD therapy [7-9]. In an animal model, we have demonstrated that adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of TGFβ to the peritoneum results in functional and structural changes similar to those seen in patients on long-term PD [10]. Peritoneal fibrosis and angiogenesis have been demonstrated to be associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of mesothelial cells [11] and we have shown that TGFβ induces a pattern of EMT similar to that which is seen in the peritoneal tissues of PD patients [12].

Hypoxia has been linked to angiogenesis [13], fibrosis [14] and EMT [15]. The cellular hypoxic response is mediated through several factors including hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF). HIF1α protein expression is tightly regulated by oxygen sensitive enzymes and in a low oxygen environment, binds to the constitutively expressed HIF1β, translocates to the nucleus and induces a characteristic pattern of gene expression [16]. Studies have identified an association between hypoxia and fibrosis in the liver [17], lung [18] and kidney [19]. There is extensive evidence that hypoxia directly up-regulates TGFβ1 and independently regulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [20, 21].

HIF1α has been demonstrated to have significant fibrogenic and angiogenic effects in vivo. Mice with a conditional hepatic deletion of HIF1α demonstrated less fibrosis in a common model of cirrhosis [22]. Furthermore, HIF1α has been linked to EMT in renal tubular epithelial cells [15]. The mechanism of HIF1α-associated EMT appears to involve regulation of metalloproteinases and the zinc finger regulatory proteins SNAI1 (Snail) [23], SNAI2 (Slug) [24] and Twist [25].

Rapamycin is a commonly used immunosuppressive agent that inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and has been demonstrated to down-regulate hypoxia-induced HIF1α[26]. Rapamycin therefore has anti-angiogenic effects through blockade of HIF1α-induced VEGF expression [27]. Because of the association between HIF1α and fibrosis, rapamycin has been demonstrated to have anti-fibrotic activity in a number of mouse models including the kidney [28, 29], liver [30] and two models of systemic sclerosis [31]. Everolimus, a related mTOR inhibitor, has been demonstrated to have a positive effect in a model of cyclohexidine gluconate-induced peritoneal fibrosis [32]. Furthermore, rapamycin blocks some of the EMT effects of TGFβ in mesothelial cell culture [33].

The interaction between fibrosis, angiogenesis and hypoxia is complex and likely organ specific. Peritoneal tissues are poorly vascularized and peritoneal injury appears to follow a classic wound healing response with induction of new blood vessels and associated deposition of connective tissue [34]. This is distinct from the fibrogenic response in highly vascularized organs such as the lung or kidney. In the lung, it appears as though fibrotic foci demonstrate angiogenic stimuli but a loss of blood vessels related to increased anti-angiogenic factors [18]. The same loss of blood vessels is observed in the renal interstitium after glomerular injury [35]. We hypothesize that in peritoneal tissue, fibrogenesis induces hypoxia, and this can potentiate angiogenesis and maintain and amplify the fibrotic response.

Materials and methods

Recombinant adenoviruses

The construction of the adenovirus vector AdTGFβ1 has been previously described [36]. AdTGFβ1 expresses biologically active TGFβ1. AdHIF1α (mut) was constructed as previously described [37]. Briefly, the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD, amino acids from 392 to 511) was excised from the full-length HIF1α. Missense mutations (Pro567Thr and Pro658Gln) were introduced. These mutations are necessary to fully activate HIF1α[38]. We also constructed an adenovirus expressing the full-length HIF1α. A null adenovirus (AdDL) was used for control.

Animal studies

Animals were treated in accordance with guideline of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. C57Bl/6 mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were treated with AdTGFβ1, AdHIF1α, AdHIF1α (mut) or AdDL at a dose of 1.5 × 108 plaque forming units diluted in 100 μl in PBS by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection and animals were killed on days 10 or 21 after infection. Rapamycin (generously provided by Wyeth Canada) or vehicle was administered by oral gavage to mice treated with AdTGFβ1 or AdDL starting on day 3 and continuing daily at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg. Before the mice were killed, 5 ml of 4.25% glucose dialysis solution (Baxter Healthcare, McGaw Park, IL, USA) was administered by i.p. injection and then recovered 15 min. later. The entire anterior abdominal wall was removed and half was taken for histology and half for RNA extraction. Omental tissue was taken and frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein extraction. The in vivo effects of rapamycin were confirmed in a repeat experiment.

Smad3−/− mice were generously provided by Dr. A. Roberts. These mice were generated by removal of exon 8 of the Smad3 gene in mice of background 127SV/EV x C57BL/6 as per Yang and colleagues [39]. Smad3−/− and littermate Smad3+/+ mice were infected with AdHIF1α (mut) at a dose of 1.5 × 108 plaque forming units diluted in 100 μl in PBS by i.p. injection and animals were killed on day 21 after infection.

Immunohistochemical analysis

C57Bl/6 mice, 10 days after treatment with i.p. AdTGFβ1 or AdDL, received a tail vein injection of 60 mg/kg of pimonidazole (HPI, Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) dissolved in 0.9% saline. One hour later, anterior abdominal wall tissue was taken and stained for pimonidazole using a mAb to pimonidazole (HPI, Inc.) and a secondary Fab antimouse antibody. To assess the effects of rapamycin treatment on angiogenesis, paraffin-embedded tissues of anterior abdominal wall from these mice were sectioned and immunohistochemical analysis was performed using vWf-related antigen (Dako Corp., Carpenteria, CA, USA). The density of blood vessels in the superficial 200 μm layer of the submesothelium and submesothelial thickness of the parietal peritoneum were analysed using Northern Eclipse software (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Cell culture

Mesothelial cells were isolated from rat peritoneal tissue and cultured as previously described [10]. Cells were exposed to media alone or rapamycin (provided by Wyeth Canada) at concentrations of 1, 10 or 50 ng/ml. Cells were then exposed to 2.5 ng/ml of recombinant TGFβ1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 24 hrs. In a separate experiment, cells were treated with rapamycin and then grown for 12 or 24 hrs in a hypoxic environment (1% O2) or normoxia (HeraCell incubator, Thermo Scientific, Nepean, ON, Canada).

Quantitative PCR

mRNA was extracted from primary rat mesothelial cells or from the peritoneum of killed animals by immersing the parietal peritoneal surface in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada) for 20 min. RNA was extracted from Trizol according to the manufacturer's instruction. RNA (1 μg) then was reverse-transcribed using a standard protocol (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR for plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1, VEGF, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), and SNAI1, SNAI2, type 1 collagen, and HIF1α was performed on mRNA using an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). mRNA quantification was referenced to Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and 18S. Data were similar with each reference gene and mRNA. Results referenced to GAPDH are shown.

Protein analysis

Protein (25 μg) was electrophoresed on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred and probed with an antibody to HIF1α (R&D Systems) or β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada). Band density was measured using Scion Image Software (Scion Corp, Frederick MD, USA). VEGF in cell culture supernatant was measured by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test. In order to test the independent effects of TGFβ1 or hypoxia and rapamycin in mesothelial cell culture experiments we used two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test.

Results

TGFβ1-induced peritoneal fibrosis leads to a hypoxic response

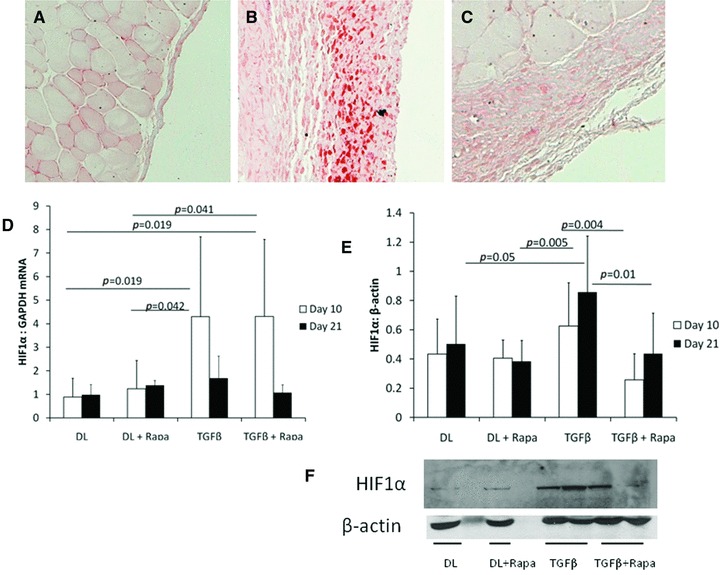

Ten days after infection with an adenovirus expressing active TGFβ1 (AdTGFβ1), we demonstrated increased cellular localization of pimonidazole in the submesothelial fibroproliferative zone (Fig. 1A–C). Pimonidazole is retained in hypoxic tissue in the presence of oxygen tension below 10 mmHg [40]. Tissue hypoxia was specific for TGFβ1-treated animals and was not seen in the peritoneum of control adenovirus-treated animals (Fig. 1A). Animals not administered pimonidazole were used to demonstrate antibody specificity (Fig. 1C). HIF1α gene expression was increased in the peritoneal tissue at day 10 after infection with AdTGFβ1 compared with control adenovirus-treated animals. Three days after adenovirus infection, animals received the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin by oral gavage. Rapamycin did not have an effect on HIF1α gene expression (Fig. 1D). Measurable increase in HIF1α protein expression was delayed until day 21 (Fig. 1E and F). HIF1α protein expression was significantly reduced in animals treated with rapamycin.

Fig 1.

(A–C) Sections of mouse peritoneal tissue stained for pimonidazole 10 days after injection (N = 3/group). (A) Mouse treated with AdDL showed no submesothelial thickening and no hypoxic response. (B) Peritoneum of AdTGFβ1-treated mouse revealed increased hypoxia in the submesothelium. (C) Control section from a mouse receiving AdTGFβ1 but no pimonidazole. All sections were taken at 200× magnification. (D) HIF1α gene expression was increased by AdTGFβ1 10 days after infection. (E) HIF1α protein is up-regulated in peritoneal tissue from AdTGFβ1-treated animals at 21 days after adenoviral infection. HIF1α was significantly down-regulated by rapamycin treatment at both 10 and 21 days after adenovirus infection. (F) Representative blot is shown (N = 4 animals/group for HIF1α analysis).

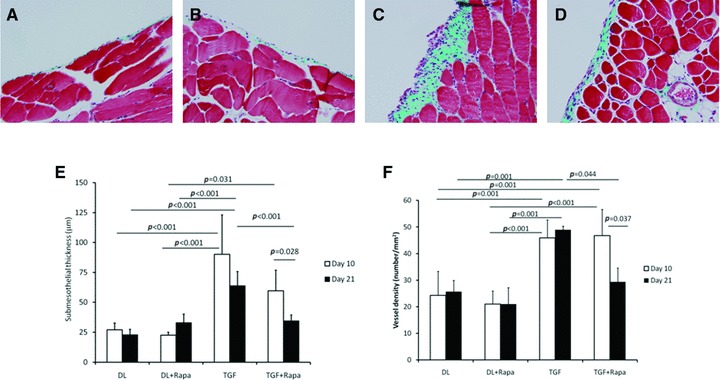

Rapamycin inhibited TGFβ1-induced submesothelial angiogenesis

Control adenovirus infection did not induce any substantial histologic changes to the peritoneal membrane (Fig. 2A). Rapamycin treatment had no effect on the peritoneum in control adenovirus-treated animals (Fig. 2B). TGFβ-induced significant submesothelial thickening and angiogenesis as seen in Figure 2C. These changes are quantified in Figure 2E and F. Rapamycin had no effect on peritoneal histology 10 days after adenovirus infection, but 21 days after infection, rapamycin treatment significantly reduced the number of blood vessels and the submesothelial thickening induced by TGFβ1. These results were confirmed in a second, separate experiment (data not shown).

Fig 2.

(A–D) Masson's trichrome stained sections of the anterior abdominal wall in animals treated with (A) control adenovirus (DL), (B) AdDL + rapamycin, (C) AdTGFβ1 (TGF) or (D) AdTGFβ1 + rapamycin. Sections from animals 21 days after adenovirus infection are shown. Original magnification was 200×. (E) Submesothelial thickening and (F) blood vessel density in the superficial 200 μm layer are quantified (N = 5 animals/group; results were confirmed in a separate experiment).

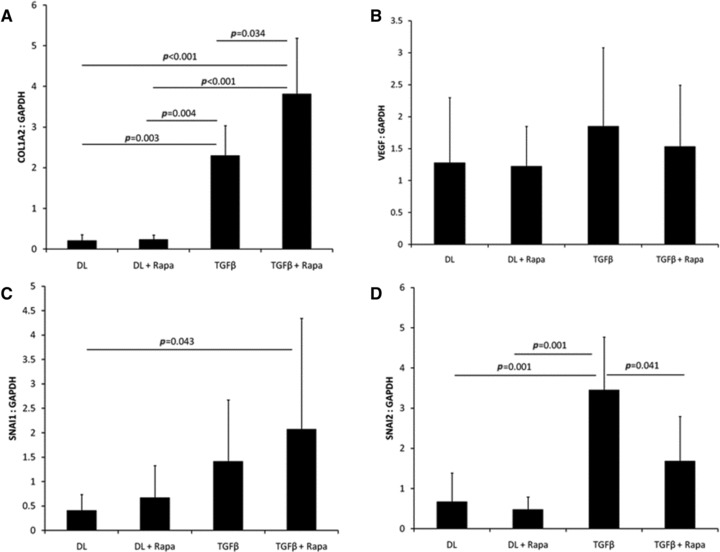

Rapamycin treatment did not affect fibrogenic gene expression

Type 1 collagen gene expression was significantly elevated in animals treated with AdTGFβ1 (Fig. 3A) 10 days after adenovirus infection. Interestingly, treatment with rapamycin in animals infected with AdTGFβ1 further increased collagen gene expression. Changes in VEGF gene expression after infection with AdTGFβ1 were not significant (Fig. 3B). Gene expression of the zinc finger regulatory proteins SNAI1 (Snail) and SNAI2 (Slug) was increased in the AdTGFβ1-treated animals (Fig. 3C). Rapamycin inhibited SNAI2 but not SNAI1 gene expression (Fig. 3D).

Fig 3.

mRNA was extracted from the peritoneal surface of the anterior abdominal wall 10 days after adenovirus infection. Gene expression was assayed using quantitative real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH expression. The expression of (A) type 1 collagen, (B) VEGF, (C) SNAI1 and (D) SNAI2 genes were assessed in animals treated with AdDL (DL), AdDL + rapamycin, AdTGFβ1 (TGFβ1) or AdTGFβ1 + rapamycin (N = 5/group).

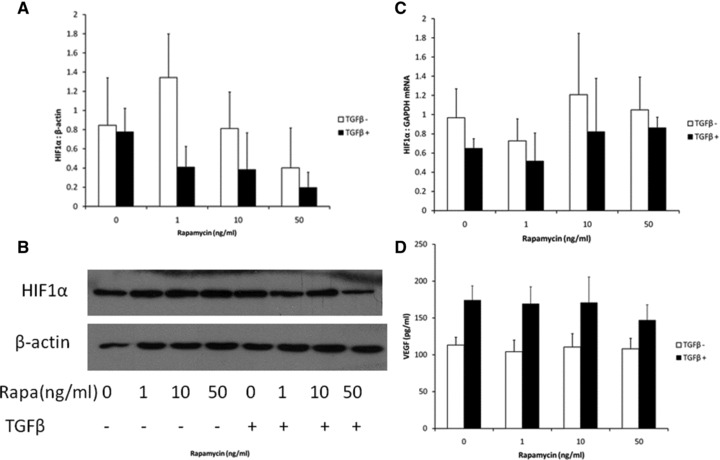

Rapamycin had no effects on TGFβ1-induced changes in mesothelial cell culture, but significantly blocked the response to hypoxia

We studied induction of HIF1α after 24 hrs of exposure to recombinant TGFβ1. TGFβ1 did not significantly induce HIF1α protein or gene expression at this time point (Fig. 4A–C) and HIF1α protein and gene expression was not significantly affected by rapamycin. TGFβ1 significantly increased VEGF gene expression in mesothelial cell culture and rapamycin had no effect on this (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Primary rat mesothelial cells were cultured and exposed to recombinant TGFβ1 (2.5 ng/ml) and varying concentrations of rapamycin. Cells were harvested for protein or mRNA. Supernatant was taken for VEGF ELISA. (A) Western blot for HIF1α referenced to β-actin. (B) Blots were quantified with a representative blot shown. (C) HIF1α gene expression by quantitative real time PCR referenced to GAPDH (for both protein and gene expression of HIF1α, P = NS, TGFβ versus no TGFβ and P = NS for the effect of rapamycin). (D) Cell culture supernatant was analysed for VEGF by ELISA. TGFβ1-induced VEGF expression (P < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA) and again rapamycin had no significant effect on this (N = 4 samples for each group at each time point).

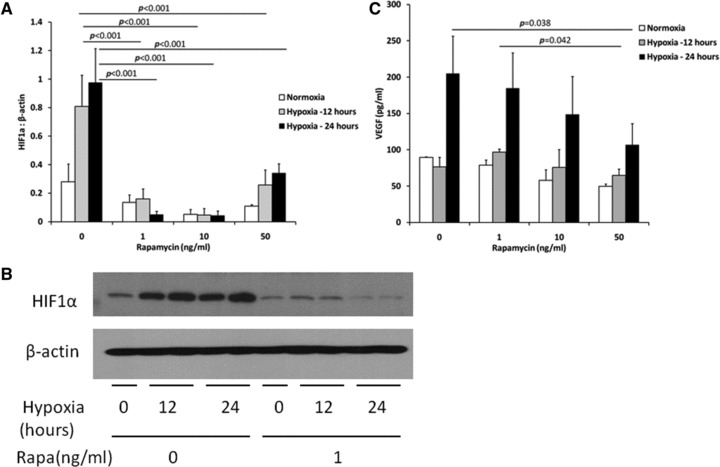

As previously demonstrated [26], rapamycin significantly reduced HIF1α and VEGF expression in mesothelial cells exposed to 1% oxygen for 12 or 24 hrs (Fig. 5). Hypoxia significantly up-regulated HIF1α protein expression. Rapamycin significantly decreased HIF1α protein expression at both 12 and 24 hrs (Fig. 5A and B). By two-way ANOVA, hypoxia significantly increased VEGF expression after 24 hrs of hypoxia. Rapamycin significantly decreased hypoxia-induced VEGF expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

Primary rat mesothelial cells were cultured and exposed to varying concentrations of rapamycin and then grown for 12 or 24 hrs in normal or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions. (A) Hypoxia significantly up-regulated HIF1α protein expression (P = 0.006, normoxia versus 12 hrs hypoxia; P = 0.001, normoxia versus 24 hrs hypoxia, two-way ANOVA) and this was blocked by rapamycin. (B) Representative blot. (C) Cell culture supernatant was assayed for VEGF by ELISA. Hypoxia significantly increased VEGF expression after 24 hrs (P < 0.001 for 24 hrs hypoxia compared with 12 hrs, or normoxia by two-way ANOVA) and this effect was blocked by rapamycin (n = 3 samples for each group).

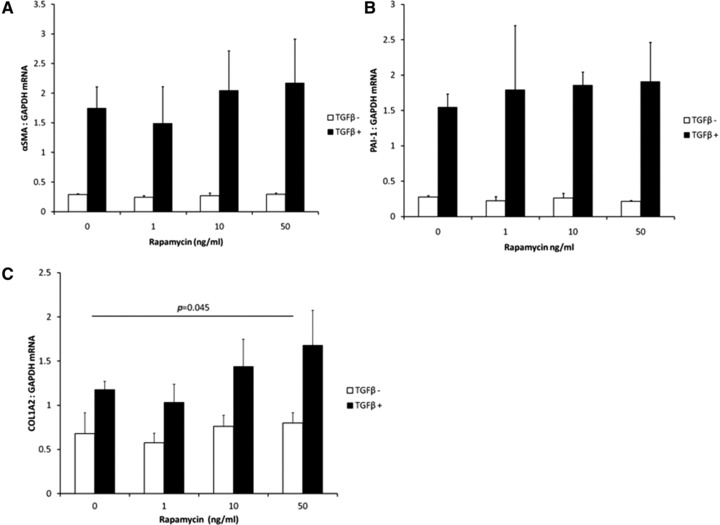

Rapamycin exacerbated TGFβ1-induced fibrogenic changes

In primary mesothelial cells, we found that TGFβ1 significantly induced gene expression of αSMA, PAI-1 and type 1 collagen (Fig. 6). Rapamycin did not have an independent effect on fibrogenic gene expression, except for expression of type 1 collagen where rapamycin augmented the effect of TGFβ1 (Fig. 6C).

Fig 6.

Primary rat mesothelial cells were cultured and exposed to recombinant TGFβ1 (2.5 ng/ml) and varying concentrations of rapamycin. Gene expression of (A) αSMA, (B) PAI-1 or (C) type 1 collagen was assayed using quantitative real time PCR and referenced to GAPDH. These three genes were all significantly up-regulated by TGFβ1 (P < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA). Rapamycin augmented the effect of TGFβ1 on increasing type 1 collagen gene expression (P = 0.023 by two-way ANOVA, n = 3 samples/group).

Overexpression of HIF1α induces angiogenesis and increased submesothelial thickening in the peritoneum

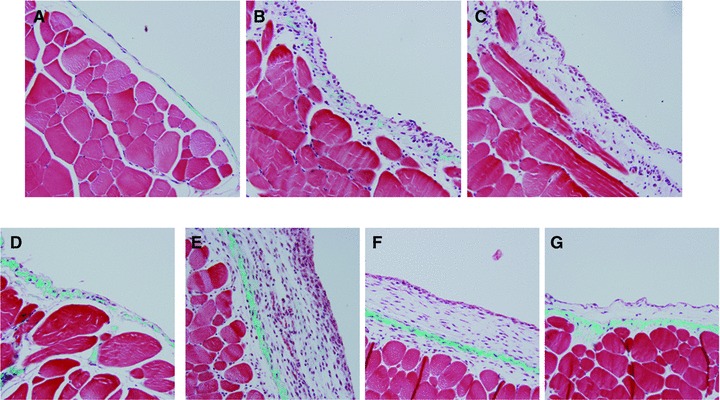

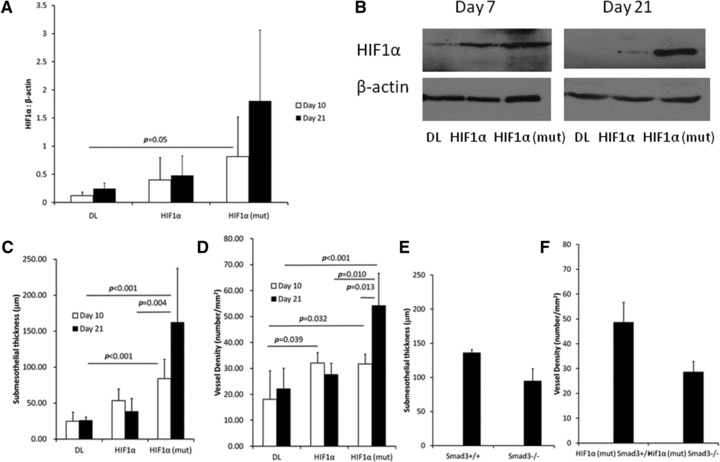

The peritoneum exposed to AdHIF1α (full-length HIF1α) was similar to AdHIF1α (mut) (active HIF1α) 10 days after infection (Fig. 7B and C). Compared to control adenovirus-treated animals (Fig. 7A) there was increased submesothelial thickening with angiogenesis and cellular proliferation. By day 21, the changes in the peritoneum infected with AdHIF1α had generally resolved (Fig. 7D). In contrast, AdHIF1α (mut) induced a progressive submesothelial thickening and angiogenesis (Fig. 7E). The differences in response to AdHIF1α and AdHIF1α (mut) is likely a result of a difference in persistence in expression of HIF1α in the omental tissue of these mice (Fig. 8A and B). AdHIF1α (mut) led to prolonged expression that was measurable to 21 days after infection.

Fig 7.

Masson's trichrome stained sections from the anterior abdominal wall from C57Bl/6 mice 10 days after injection with (A) control adenovirus (AdDL), (B) adenovirus expressing full-length HIF1α (AdHIF1α), (C) adenovirus expressing mutated, constitutively active HIF1α[AdHIF1α (mut)]. Anterior abdominal wall 21 days after injection with (D) AdHIF1α, (E) AdHIF1α (mut). In order to assess the role of TGFβ signalling in HIF1α-induced peritoneal changes, AdHIF1α (mut) was infected into the peritoneum of (F) Smad3+/+ or (G) Smad3–/– mice and tissue taken 21 days after infection.

Fig 8.

(A) Expression of HIF1α in omental tissue from animals treated with AdHIF1α or AdHIF1α (mut) (n = 4 samples/group). (B) Representative blot shown. (C, D) Quantification of changes seen in the peritoneum of C57Bl/6 mice treated with AdHIF1α or AdHIF1α (mut). (E, F) Smad3+/+ or Smad3–/– mice were infected with AdHIF1α (mut). Twenty-one days later, there were no significant differences in submesothelial thickness (E) or vascular density (F) (N = 5–8 animals/group).

HIF1α-induced expression of fibrogenic genes but not VEGF is Smad3 dependent

As the changes after AdHIF1α (mut) appeared to be maximal 21 days after infection, we chose this time point to study animals deficient in the key TGFβ signalling protein Smad3 (Smad3−/−) using littermate Smad3+/+ mice as control. Histologically, there were subtle differences between Smad3+/+ and Smad3−/− mice 21 days after infection with AdHIF1α(mut) (shown in Fig. 7F and G and quantified in Fig. 8C and D). These changes were not statistically significant when quantified; however, there was a trend to decreased submesothelial thickening and angiogenesis, suggesting that part of the HIF1α response may be Smad3 dependent.

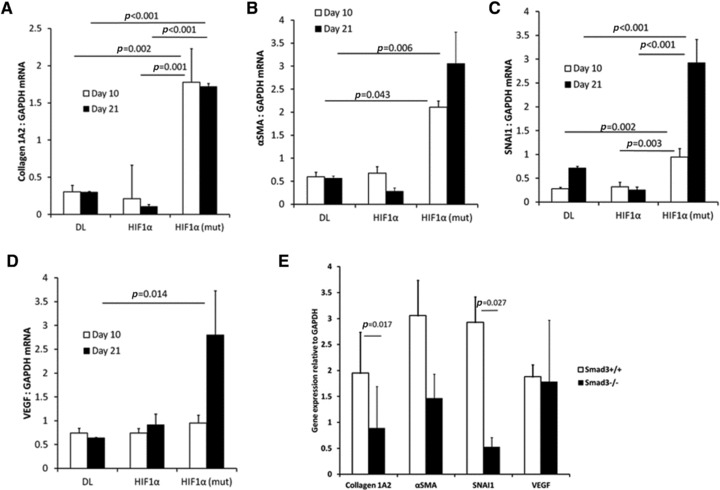

RNA was extracted from the anterior abdominal wall of C57Bl/6, Smad3+/+ or Smad3−/− mice treated with AdDL, AdHIF1α or AdHIF1α (mut) and assayed using quantitative real time PCR (Fig. 9). The expression of type 1 collagen (Fig. 9A), αSMA (Fig. 9B) and SNAI1 (Fig. 9C) were all up-regulated after AdHIF1α (mut) but not AdHIF1α infection. The gene expression of type1 collagen and SNAI1 were both Smad3 dependent, with expression significantly reduced in Smad3−/− mice. In contrast, VEGF expression was similar in Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ mice treated with AdHIF1α (mut).

Fig 9.

RNA was extracted from C57Bl/6 mice treated with control adenovirus (AdDL), AdHIF1α or AdHIF1α (mut). Collagen 1A2 (A), αSMA (B), SNAI1 (C) and VEGF (D) are all up-regulated by HIF1α (mut) adenovirus. (E) mRNA from Smad3+/+ or Smad3–/– mice 21 days after treatment with AdHIF1α (mut) was assayed using quantitative real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Collagen and SNAI1 were significantly up-regulated in Smad3+/+ but not Smad3–/– mice. VEGF was not differentially regulated (N = 5–8 mice/group were analysed).

Discussion

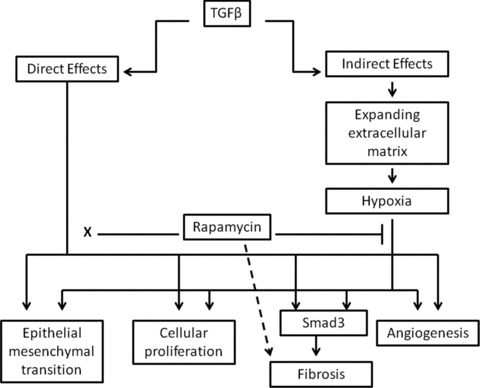

Our results indicate that the expanding extracellular matrix induced by TGFβ in the peritoneum is hypoxic, and this hypoxia potentiates and prolongs fibrogenesis and angiogenesis. We interpret our results to suggest that after overexpression of TGFβ1, there is a period of TGFβ1-driven fibrosis and angiogenesis. This is followed by a hypoxia-mediated prolongation of this initial wound healing response. The later hypoxia-driven response is inhibited by rapamycin, but rapamycin has no effect on the earlier TGFβ1-mediated events (Fig. 10). This is supported by cell culture experiments where rapamycin blocks hypoxia-induced VEGF, but has no effect on TGFβ1-induced VEGF.

Fig 10.

Hypothesized interaction between direct effects of TGFβ and secondary effects of hypoxia. TGFβ has direct effects on peritoneal tissues including EMT, cellular proliferation, fibrosis and angiogenesis. The TGFβ-induced expanding extracellular matrix is hypoxic, and this drives a similar but delayed response. The hypoxia-induced effects are blocked by rapamycin, whereas rapamycin has no effect of the TGFβ-induced effects (denoted by x). The profibrotic effects of hypoxia are Smad3 dependent. In vitro, rapamycin up-regulates type 1 collagen in TGFβ-treated mesothelial cells (dashed arrow).

The interaction between hypoxia and fibrosis is complex. In lung and renal fibrosis, the prevailing paradigm suggests that vascular rarefaction is a primary event, with subsequent hypoxia-driven fibrosis [18, 35, 41]. Peritoneal tissues are comparatively less vascularized than the lung or kidney, so the expanding fibrotic tissue requires blood vessel growth to sustain this; when the expanding submesothelium outstrips its vascular supply, a hypoxic angiogenic response ensues.

The tight regulation of HIF1α has been described in detail [16]. In our studies, we identified that TGFβ1-induced peritoneal fibrosis led to both hypoxia, and increased expression of HIF1α. Interestingly, in our results, TGFβ1 had no effect on HIF1α gene and protein expression in mesothelial cell culture (Fig. 4A and B). Several previous studies have identified a transient TGFβ1-mediated induction of HIF1α either through protein stabilization [42] or interaction between HIF1α and Smad signalling proteins [43]. These effects were seen transiently at an earlier time point (6 hrs). We looked at a later time point (24 hrs) as we were interested in the interaction between rapamycin and TGFβ1-induced fibrogenic gene expression (Fig. 6).

The angiogenic effects of HIF1α are well known [37]. HIF1α has also been demonstrated to have fibrogenic effects directly through up-regulation of fibrogenic factors [44] and EMT [15]. In our experiments, we used an adenovirus expressing the full-length HIF1α or a mutated HIF1α with the ODDD excised [37]. AdHIF1α (mut) led to prolonged expression of HIF1α and persisting histologic changes (Figs 7 and 8). Specifically, HIF1α overexpression led to prolonged angiogenesis and fibrosis measured by increased submesothelial thickening, blood vessel density and increased expression of fibrogenic-associated genes (Fig. 9).

The mechanism of HIF1α-induced fibrosis is not clear. Some studies have identified a necessity for TGFβ signalling [20, 21, 45], whereas other studies demonstrate a TGFβ-independent path for HIF1α-induced fibrosis [17, 46]. In order to test this in our model, we infected animals lacking the Smad3 signalling molecule with AdHIF1α (mut). We have previously shown that these mice are resistant to TGFβ1-induced fibrosis and angiogenesis, but respond normally to VEGF [47]. Gene expression of the fibrosis-associated genes type 1 collagen and SNAI1 was significantly reduced in Smad3−/− mice infected with AdHIF1α(mut) (Fig. 9). VEGF gene expression was not significantly different between Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ mice treated with AdHIF1α (mut), suggesting that the fibrogenic effects, but not the angiogenic effects, of HIF1α are Smad3 dependent.

Rapamycin is a bacterial macrolide that binds with high affinity to mTOR. It is used clinically in renal transplantation for its immunosuppressant properties [27]. mTOR activates p70 S6 kinase which is involved in regulating RNA translation and protein expression and therefore has an effect on cellular growth and proliferation [48]. Rapamycin has been demonstrated to block HIF1α gene expression and thus has anti-angiogenic properties in the setting of malignancy [26]. Rapamycin has also been shown to be an effective anti-fibrotic agent in 2 models of renal injury [49, 50] and a model of systemic sclerosis [31]. Everolimus has been shown to prevent progression of peritoneal fibrosis in a chemical irritant model of peritoneal injury [32]. mTOR inhibition has been demonstrated to prevent EMT as a mechanism of anti-fibrotic activity. In mesothelial cell culture, rapamycin up-regulated E-Cadherin as an epithelial protective mechanism [33]. This was confirmed in an animal model of renal fibrosis [29]. Lamouille and colleagues did not find that rapamycin had a direct EMT inhibitory effect in cell culture [51] and we found that rapamycin had an inhibitory effect on mesothelial EMT, but only in animals lacking Smad3 signalling [47].

Our results suggest that rapamycin has a significant anti-angiogenic effect when angiogenesis is driven by hypoxic response. Rapamycin did not have a significant anti-fibrotic effect, and in mesothelial cell culture, rapamycin tended to accentuate TGFβ1-induced up-regulation of pro-fibrotic cytokines. This appears to be contrary to other published in vitro data [52, 53]. In extensive in vivo work, rapamycin appears to be ‘anti-fibrotic’[54]. However, it is difficult to dissociate anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory properties in these in vivo experiments. These other effects of rapamycin may lead to a secondary anti-fibrotic response. Previous cell culture work has generally been carried out in fibroblasts [52] or mesangial cells [55]. Our work was carried out in a primary epithelial cell type which may explain the differential response we observed. Furthermore, in vitro it is necessary to separate the anti-proliferative effects from the anti-fibrotic effects which may confound these results [55].

Rapamycin did block TGFβ1-induced expression of SNAI2 (Fig. 3D) and this is a potential mechanism whereby rapamycin may inhibit mesothelial EMT and indirectly influence peritoneal fibrosis. Our results concerning the effects of hypoxia and rapamycin on peritoneal EMT are preliminary, and further experiments to detail this interaction are required.

In summary, TGFβ1-induced peritoneal fibrosis leads to a secondary hypoxic response that amplifies the initial fibrosis and angiogenesis and this secondary response is sensitive to mTOR inhibition. Our findings suggest that HIF1α is responsible for some of these hypoxia-associated responses.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by Wyeth Canada and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Additional funding is provided by St. Joseph's Healthcare, Hamilton, ON. P. J. Margetts is a CIHR Clinician Scientist.

Conflict of interest

This research is funded by Wyeth Canada. The authors have no other conflicts with respect to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Davies SJ, Bryan J, Phillips L, et al. Longitudinal changes in peritoneal kinetics: the effects of peritoneal dialysis and peritonitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:498–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flessner MF. The effect of fibrosis on peritoneal transport. Contrib Nephrol. 2006;150:174–80. doi: 10.1159/000093518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brimble KS, Walker M, Margetts PJ, et al. Meta-analysis: peritoneal membrane transport, mortality, and technique failure in peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2591–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda K, Hamada C, Nakayama M, et al. Impact of uremia, diabetes, and peritoneal dialysis itself on the pathogenesis of peritoneal sclerosis: a quantitative study of peritoneal membrane morphology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:720–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03630807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combet S, Ferrier ML, Van LM, et al. Chronic uremia induces permeability changes, increased nitric oxide synthase expression, and structural modifications in the peritoneum. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2146–57. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moona SJ, Hana SH, Kim DK, et al. Risk factors for adverse outcomes after peritonitis-related technique failure. Perit Dial Int. 2008;28:352–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho JH, Hur IK, Kim CD, et al. Impact of systemic and local peritoneal inflammation on peritoneal solute transport rate in new peritoneal dialysis patients: a 1-year prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1964–73. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai KN, Lai KB, Szeto CC, et al. Growth factors in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis effluent. Their relation with peritoneal transport of small solutes. Am J Nephrol. 1999;19:416–22. doi: 10.1159/000013488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gangji AS, Brimble KS, Margetts PJ. Association between markers of inflammation, fibrosis and hypervolemia in peritoneal dialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2009;28:354–8. doi: 10.1159/000232937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margetts PJ, Kolb M, Galt T, et al. Gene transfer of transforming growth factor-beta1 to the rat peritoneum: effects on membrane function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2029–39. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanez-Mo M, Lara-Pezzi E, Selgas R, et al. Peritoneal dialysis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:403–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margetts PJ, Bonniaud P, Liu L, et al. Transient overexpression of TGF-{beta}1 induces epithelial mesenchymal transition in the rodent peritoneum. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:425–36. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao D, Johnson RS. Hypoxia: a key regulator of angiogenesis in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:281–90. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fine LG, Norman JT. Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: from hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2008;74:867–72. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, et al. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3810–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI30487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxwell P. HIF-1: an oxygen response system with special relevance to the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2712–22. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000092792.97122.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corpechot C, Barbu V, Wendum D, et al. Hypoxia-induced VEGF and collagen I expressions are associated with angiogenesis and fibrogenesis in experimental cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35:1010–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, Schiemann WP, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a role in aberrant angiogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:242–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1151OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manotham K, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, et al. Evidence of tubular hypoxia in the early phase in the remnant kidney model. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000125614.35046.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa T, Lan HY, Zhu HJ, et al. Differential regulation of VEGF by TGF-beta and hypoxia in rat proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F658–64. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00040.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou G, Dada LA, Wu M, et al. Hypoxia-induced alveolar epithelial-mesenchymal transition requires mitochondrial ROS and hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1120–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00007.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon JO, Welch TP, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Reduced liver fibrosis in hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G582–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90368.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundgren K, Nordenskjold B, Landberg G. Hypoxia, Snail and incomplete epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1769–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang CH, Yang WH, Chang SY, et al. Regulation of membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase by SLUG contributes to hypoxia-mediated metastasis. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1371–82. doi: 10.1593/neo.91326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun S, Ning X, Zhang Y, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha induces Twist expression in tubular epithelial cells subjected to hypoxia, leading to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1278–87. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7004–14. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7004-7014.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guba M, von Breitenbuch P, Steinbauer M, et al. Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumour growth by antiangiogenesis: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:128–35. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lloberas N, Cruzado JM, Franquesa M, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway blockade slows progression of diabetic kidney disease in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1395–404. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu MJ, Wen MC, Chiu YT, et al. Rapamycin attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2029–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu J, Wu J, Frizell E, et al. Rapamycin inhibits hepatic stellate cell proliferation in vitro and limits fibrogenesis in an in vivo model of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1198–204. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshizaki A, Yanaba K, Yoshizaki A, et al. Treatment with rapamycin prevents fibrosis in tight-skin and bleomycin-induced mouse models of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2476–87. doi: 10.1002/art.27498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duman S, Bozkurt D, Sipahi S, et al. Effects of everolimus as an antiproliferative agent on regression of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in a rat model. Adv Perit Dial. 2008;24:104–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguilera A, Aroeira LS, Ramirez-Huesca M, et al. Effects of rapamycin on the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Int J Artif Organs. 2005;28:164–9. doi: 10.1177/039139880502800213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel P, West-Mays J, Kolb M, et al. Platelet derived growth factor B and epithelial mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cina DP, Xu H, Liu L, et al. Renal tubular angiogenic dysregulation in anti-Thy1.1 glomerulonephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F488–98. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00214.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sime PJ, Xing Z, Graham FL, et al. Adenovector-mediated gene transfer of active transforming growth factor-beta1 induces prolonged severe fibrosis in rat lung. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:768–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI119590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly BD, Hackett SF, Hirota K, et al. Cell type-specific regulation of angiogenic growth factor gene expression and induction of angiogenesis in nonischemic tissue by a constitutively active form of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Circ Res. 2003;93:1074–81. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000102937.50486.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonniaud P, Margetts PJ, Kolb M, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer of connective tissue growth factor in the lung induces transient fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:770–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1254OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Letterio JJ, Lechleider RJ, et al. Targeted disruption of SMAD3 results in impaired mucosal immunity and diminished T cell responsiveness to TGF-beta. EMBO J. 1999;18:1280–91. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberger C, Rosen S, Paliege A, et al. Pimonidazole adduct immunohistochemistry in the rat kidney: detection of tissue hypoxia. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;466:161–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-352-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farkas L, Farkas D, Ask K, et al. VEGF ameliorates pulmonary hypertension through inhibition of endothelial apoptosis in experimental lung fibrosis in rats. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1298–311. doi: 10.1172/JCI36136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMahon S, Charbonneau M, Grandmont S, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1 stabilization through selective inhibition of PHD2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24171–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basu RK, Hubchak SC, Hayashida T, et al. Interdependence of HIF-1{alpha} and TGF-{beta}/Smad3 signaling in normoxic and hypoxic renal epithelial cell collagen expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F898–905. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00335.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Copple BL, Bustamante JJ, Welch TP, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent production of profibrotic mediators by hypoxic hepatocytes. Liver Int. 2009;29:1010–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki A, Kusakai G, Shimojo Y, et al. Involvement of transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in hypoxia-induced tolerance to glucose starvation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31557–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen CP, Yang YC, Su TH, et al. Hypoxia and transforming growth factor-beta 1 act independently to increase extracellular matrix production by placental fibroblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1083–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel P, Sekiguchi Y, Oh KH, et al. Smad3-dependent and -independent pathways are involved in peritoneal membrane injury. Kidney Int. 2010;77:319–28. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong J, Peng J, Zhang H, et al. Role of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in rapamycin-mediated cell cycle regulation and chemosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1961–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang S, Wilkes MC, Leof EB, et al. Noncanonical TGF-beta pathways, mTORC1 and Abl, in renal interstitial fibrogenesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F142–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00320.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kramer S, Wang-Rosenke Y, Scholl V, et al. Low-dose mTOR inhibition by rapamycin attenuates progression in anti-thy1-induced chronic glomerulosclerosis of the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F440–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00379.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamouille S, Derynck R. Cell size and invasion in TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition is regulated by activation of the mTOR pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:437–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshizaki A, Yanaba K, Yoshizaki A, et al. Treatment with rapamycin prevents fibrosis in tight-skin and bleomycin-induced mouse models of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2476–87. doi: 10.1002/art.27498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poulalhon N, Farge D, Roos N, et al. Modulation of collagen and MMP-1 gene expression in fibroblasts by the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin. A direct role as an antifibrotic agent? J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33045–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neef M, Ledermann M, Saegesser H, et al. Low-dose oral rapamycin treatment reduces fibrogenesis, improves liver function, and prolongs survival in rats with established liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:786–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lock HR, Sacks SH, Robson MG. Rapamycin at subimmunosuppressive levels inhibits mesangial cell proliferation and extracellular matrix production. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F76–81. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00128.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]