Abstract

The proepicardial-derived epicardium covers the myocardium and after a process of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) forms epicardium-derived cells (EPDCs). These cells migrate into the myocardium and show an essential role in the induction of the ventricular compact myocardium and the differentiation of the Purkinje fibres. EPDCs are furthermore the source of the interstitial fibroblast, the coronary smooth muscle cell and the adventitial fibroblast. The possible differentiation into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells and the recently described telocyte and other cells in the cardiac stem cell niche needs further investigation. Surgically or genetically disturbed epicardial and EPDC differentiation leads to a spectrum of abnormalities varying from thin undifferentiated myocardium, which can be embryonic lethal, to a diminished coronary vascular bed with even absent main coronary arteries. The embryonic potential of EPDCs has been translated to both structural and functional congenital malformations and adult cardiac disease, like development of Ebstein’s malformation, arrhythmia and cardiomyopathies. Furthermore, the use of adult EPDCs as a stem cell source has been explored, showing in an animal model of myocardial ischemia the recapitulation of the embryonic program with improved function, angiogenesis and less adverse remodeling. Combining EPDCs and adult cardiomyocyte progenitor cells synergistically improved these results. The contribution of injected EPDCs was instructive rather than constructive. The finding of reactivation of the endogenous epicardium in ischemia with re-expression of developmental genes and renewed EMT marks the onset of a novel therapeutic focus.

Keywords: epicardium, epicardium-derived cells (EPDCs), Wilms’ tumour 1 (WT1), epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), cardiac development, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, second heart field, proepicardial organ

Development of the epicardium

The epicardium develops from the proepicardial organ located at the venous pole of the heart in continuity with the second heart field [1]. The epicardium is a mesothelial layer that forms a continuum with the coelomic lining and as such expresses many genes that are epithelial in origin like cytokeratin [2] and α4 integrin [3]. The evolutionary link to the developing excretory tract is exemplified by the expression of proteins like Wilms’ tumour 1 (WT1) [4] and podoplanin [5, 6]. The guidance of the epicardium over the looping myocardial tube, which consists of both primary and second heart field derived myocardium [7] is still not completely understood, but epicardial–myocardial interaction including retinoic acid [4, 8] as well as members of the platelet-derived growth factor signalling are of relevance [9].

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition into EPDCs

After initial spreading of the epicardium over the myocardium, several waves of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) have been described with subsequent migration into the sub-endocardial and intramyocardial location [10, 11]. The EPDCs that are essential for the isolation of atrial and ventricular myocardium, with the formation of the annulus fibrosis [12, 13] and the population of the atrioventricular cushions [10, 11], migrate into the heart relatively late. The EPDCs have been traced by using the chicken quail chimera model [10] as well as several transgenic mouse models. The most well known are GATA5 [14] and WT1 [4].

Derivatives of EPDCs

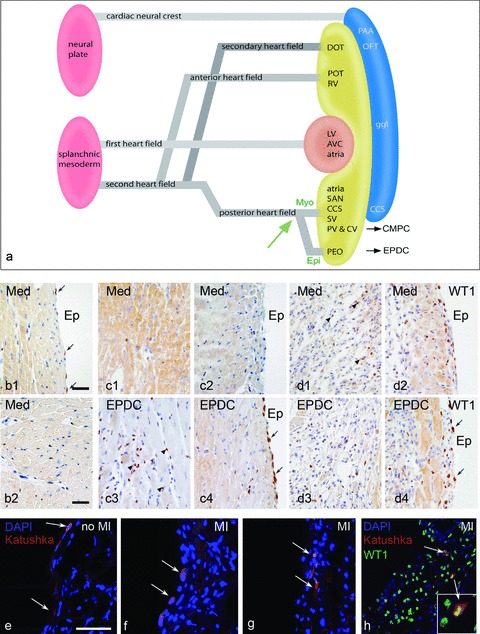

From these studies the EPDCs could be followed into their definitive position and eventual differentiation state. Unequivocally, differentiations of the cardiac fibroblast, coronary smooth muscle cell and adventitial fibroblast have been proven. Different opinions exist on the origin of the coronary endothelial cell and the cardiomyocyte. As both epicardial and myocardial cells derive from a common second heart field progenitor cell (Fig. 1a), the recent studies using the conditional Cre-lox model of WT1 [15] and Tbx18 [16] do not provide an absolute proof of the origin of cardiomyocytes from the epicardial lineage. Of interest in this respect is the described regenerative potential of the zebra fish heart [17] that shows the capacity of the epicardial lineage to stimulate the cardiac myocyte population to renewed growth without actual cellular contribution. The endothelial lineage derives from the sinus venosus and liver microvascular lining but not from the epicardium [18]. Whether there is a further link between the epicardium and other intracardiac (stem) cell populations, such as the recently described telocyte [19], needs further research.

Fig 1.

(a) Schematic representation of the first and second heart field contribution to the developing heart. The venous pole (posterior heart field) is essential as source of EPDCs and CMPCs, a differentiation in a myocardial and epicardial lineage from the progenitor population is guided by the balance of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and fibroblastic growth factor 2 (Fgf2) [27]. (b) Expression of WT1 in the surface epicardium (b1) and intramyocardially (b2) in a control adult mouse heart is very limited (arrows). Two days after MI, with injection of medium, this is not substantially altered (c1,2) except for the cases with injection of EPDCs (c3,4), where both the surface epicardium and the interstitial fibroblasts show marked WT1 expression. At day 4 after MI this phenomenon is also present in the medium injected heart (d1,2) and maintained in the heart after EPDC transplantation (d3,4). Injection of the lentiviral Katushka construct into the epicardial cavity showed, after 4 days survival, staining of the squamous surface epicardium in the control heart (e, arrows). After MI the surface epicardium becomes cuboid (f, arrows) indicative of activation and cells can be traced intramyocardially (g, arrows) after EMT, which is supported by double staining of Katushka and WT1 (h). Scale bars b1–d4:30 μm, e–h:50 μm.

Potential role of EPDCs in cardiomyopathy and valve disease

The epicardium and EPDCs with their specific supporter role in myocardial differentiation and their homing to the fibrous annulus [12, 13] and valves [10] could also indicate a role in development of pathology. It has been shown that inhibition of epicardial outgrowth can lead to deficient annulus fibrosus formation with electrophysiological evidence of the Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome [12]. Also a periostin disturbance in the EPDC deficient models could be linked to non-delamination of the endocardial cushions resulting in an Ebstein-like valve phenotype [1]. The study of cardiomyopathies and the observation of early coronary vascular disease preceding myocardial pathology have lead to a unifying concept on the role of EPDCs not only in non-compaction cardiomyopathies [1] but also in a far broader spectrum of cardiac diseases [20].

Potential of EPDCs as adult stem cells

The convincingly proven essential functions of the epicardium and the EPDCs during normal embryonic development fuelled the hypothesis that EPDCs might recapitulate some of these functions in case of cardiac disease [21]. The potential of adult human EPDCs was investigated in vitro, comparing them with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and in vivo. In vitro culture showed that they indeed acquired stem cell characteristics. EPDCs and MSCs showed many similarities, but the unique cardiac commitment of EPDCs was established by the expression of cTnT and GATA4, lacking all mature cardiomyocyte differentiation genes [22]. Up till now these experiments require replication by other groups. We also showed that human EPDCs after injection into the ischemic myocardium of an immune incompetent mouse significantly improved cardiac function, already within 2 days [23]. The beneficial effect persisted after definitive scar formation, at 6-week follow-up. The additional results were an enhanced angiogenesis of mouse origin, less loss of infarcted wall thickness and an up-regulation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in the host tissue infarct and borderzone area. The role of the exogenous EPDCs, which acquired a myofibroblast phenotype, was mainly instructive rather than constructive [23]. The results of the beneficial effect of EPDC injection was further enhanced when a mix of adult derived EPDCs and cardiomyocyte progenitors (CMPCs) was injected. The CMPCs were also instructive and did not differentiate into cardiomyocytes as was shown for the human derived CPMCs in vitro[24]. The combination worked synergistically, with these different cells having specific and separate functions. Altogether the conclusion was drawn that the observed effects were most probably based on paracrine or cell–cell interactions from the exogenous transplant with the surrounding host tissue [25].

Reactivation of endogenous epicardium after ischemia

These findings triggered a new research field on EPDC–myocardial interaction. In the recent literature there are several reports on the activation of epicardium and the interstitial fibroblasts after myocardial infarction (MI) without additional stem cell transplantation. The group of Riley, for example, reported on the activation and coronary vascular improvement through thymosine B4 [26]. The factors triggering these events are not easily understood because of the concomitant effect of the influx of inflammatory cells after MI. We observed that 4 days after MI the endogenous epicardium and the interstitial fibroblasts started to re-express WT1 (Fig. 1, compare control b1,2 with 4 days after MI d1,2), an indication of activation and dedifferentiation. This was enhanced by 2 days if additionally exogenous EPDCs were injected (Fig. 1, compare medium injected c1,2 with EPDC injected c3,4 both 2 days after MI). To substantiate whether there was also renewed endogenous epicardial EMT and migration after ischemia, we injected a lentiviral Katushka construct (a far-red fluorescent marker) into the epicardial cavity of mice with or without MI. This showed indeed that re-activation of this embryonic program took place and that surface epicardial cells had migrated into the borderzone myocardium (Fig. 1e–g) with overlapping Katushka and WT1 staining (Fig. 1h). The therapeutic potential of the endogenous epicardium is therefore a new field of investigation, supported by our data and the literature.

In conclusion, the hypothesis that epicardium and EPDCs based on their broad embryonic potential might be a valuable source of research into MI treatment strategies as well as new fields to discover cardiac disease related mechanisms, seems to hold great promise.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Lie-Venema H, Van Den Akker NM, Bax NA, et al. Origin, fate, and function of epicardium-derived cells (EPDCs) in normal and abnormal cardiac development. Sci World J. 2007;7:1777–98. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vrancken Peeters M-PFM, Mentink MMT, Poelmann RE, et al. Cytokeratins as a marker for epicardial formation in the quail embryo. Anat Embryol. 1995;191:503–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00186740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang JT, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Cell adhesion events mediated by alpha 4 integrins are essential in placental and cardiac development. Development. 1995;121:549–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Estrada OM, Lettice LA, Essafi A, et al. Wt1 is required for cardiovascular progenitor cell formation through transcriptional control of Snail and E-cadherin. Nat Genet. 2010;42:89–93. doi: 10.1038/ng.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahtab EA, Wijffels MC, Van Den Akker NM, et al. Cardiac malformations and myocardial abnormalities in podoplanin knockout mouse embryos: correlation with abnormal epicardial development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:847–57. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pombal MA, Carmona R, Megias M, et al. Epicardial development in lamprey supports an evolutionary origin of the vertebrate epicardium from an ancestral pronephric external glomerulus. Evol Dev. 2008;10:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly RG. Molecular inroads into the anterior heart field. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xavier-Neto J, Shapiro MD, Houghton L, et al. Sequential programs of retinoic acid synthesis in the myocardial and epicardial layers of the developing avian heart. Dev Biol. 2000;219:129–41. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bax NA, Lie-Venema H, Vicente-Steijn R, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor is involved in the differentiation of second heart field-derived cardiac structures in chicken embryos. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2658–69. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Peeters MP, Mentink MM, et al. Epicardium-derived cells contribute a novel population to the myocardial wall and the atrioventricular cushions. Circ Res. 1998;82:1043–52. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Männer J, Perez-Pomares JM, Macias D, et al. The origin, formation and developmental significance of the epicardium: a review. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:89–103. doi: 10.1159/000047867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolditz DP, Wijffels MC, Blom NA, et al. Epicardium-derived cells in development of annulus fibrosis and persistence of accessory pathways. Circulation. 2008;117:1508–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.726315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou B, Von GA, Ma Q, et al. Genetic fate mapping demonstrates contribution of epicardium-derived cells to the annulus fibrosis of the mammalian heart. Dev Biol. 2010;338:251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merki E, Zamora M, Raya A, et al. Epicardial retinoid X receptor alpha is required for myocardial growth and coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou B, Ma Q, Rajagopal S, et al. Epicardial progenitors contribute to the cardiomyocyte lineage in the developing heart. Nature. 2008;454:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christoffels VM, Grieskamp T, Norden J, et al. Tbx18 and the fate of epicardial progenitors. Nature. 2009;458:E8–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepilina A, Coon AN, Kikuchi K, et al. A Dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vrancken Peeters M-PFM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Mentink MMT, et al. The development of the coronary vessels and their differentiation into arteries and veins in the embryonic quail heart. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:338–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3<338::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popescu LM, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. Telocytes – a case of serendipity: the winding way from interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), via interstitial Cajal-like cells (IVLC) to telocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:729–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Poggesi C, et al. Developmental origins of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotypes: a unifying hypothesis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:317–21. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winter EM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Epicardium-derived cells in cardiogenesis and cardiac regeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:692–703. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Tuyn J, Atsma DE, Winter EM, et al. Epicardial cells of human adults can undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and obtain characteristics of smooth muscle cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:271–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter EM, Grauss RW, Hogers B, et al. Preservation of left ventricular function and attenuation of remodeling after transplantation of human epicardium-derived cells into the infarcted mouse heart. Circulation. 2007;116:917–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goumans MJ, De Boer T, Smits AM, et al. TGFb1 induces efficient differentiation of human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells into functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cell Res. 2008;1:138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter EM, Van Oorschot AA, Hogers B, et al. A new direction for cardiac regeneration therapy: application of synergistically acting epicardium-derived cells and cardiomyocyte progenitor cells. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:643–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.843722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smart N, Risebro CA, Melville AA, et al. Thymosin beta4 induces adult epicardial progenitor mobilization and neovascularization. Nature. 2007;445:177–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruithof BP, Van Wijk B, Somi S, et al. BMP and FGF regulate the differentiation of multipotential pericardial mesoderm into the myocardial or epicardial lineage. Dev Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]