Abstract

Background

Open lung biopsy in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may provide a specific etiology and change clinical management, yet concerns about complications remain. Persistent air leak is the most common postoperative complication. Risk factors in this setting are not known.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of 53 patients who underwent open lung biopsy for clinical ARDS (based on American European Consensus Conference criteria) between 1989 and 2000.

Results

Sixteen patients (30.2%) developed an air leak lasting more than 7 days or died with an air leak. Univariate analyses showed no significant correlation with age, gender, sex, corticosteroid use, diabetes, immunocompromised status, or pathologic diagnosis. A lower risk of air leak was associated with lower peak airway pressure and tidal volume, use of pressure-cycled ventilation, and use of an endoscopic stapling device. In multivariate analyses, only peak airway pressure remained a significant predictor. The risk of prolonged air leak was reduced by 42% (95% confidence interval [CI: 17% to 60%]) for every 5 cm H2O reduction in peak airway pressure.

Conclusions

The use of a lung-protective ventilatory strategy that limits peak airway pressures is strongly associated with a reduced risk of postoperative air leak after open lung biopsy in ARDS. Using such a strategy may allow physicians to obtain information from open lung biopsy to make therapeutic decisions without undue harm to ARDS patients.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), as defined by the American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) [1], represents a clinical syndrome that can manifest as the end result of a number of different pathophysiologic processes. The appropriate therapy often hinges on understanding the underlying histology. For example, steroids can rapidly reverse bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia or eosinophilic pneumonia but they can potentially worsen infectious processes. Similarly, in the case of infectious pneumonias identifying the causal microorganism can allow for appropriate antibiotic therapy. While bronchoscopy can provide some clues to the underlying histologic diagnosis, in many cases open lung biopsy would be the ideal diagnostic test. We have previously reported that open lung biopsy frequently provides information leading to changes in therapy [2]. However, open lung biopsy is not without risk in this critically ill population. Thus, the role of open lung biopsy has been limited in this setting. Identifying risk factors for complications from open lung biopsy in ARDS may allow for more rational decision-making on employing this procedure.

The most common postoperative complication of open lung biopsy noted in several studies of patients with acute respiratory failure is prolonged air leak, with an incidence rate of 3% to 22% [3–7]. Identification of baseline characteristics predictive of persistent air leak may allow for better risk stratification of patients. In addition, identification of risk factors that can be intervened upon may make biopsy safer.

Prolonged air leak is also the most common complication prolonging hospital stay in routine pulmonary resection [8], and studies have identified risk factors for prolonged postoperative air leaks in this setting. However, the majority of these cases are for lung cancer secondary to tobacco abuse, and thus emphysema in the underlying lung tissue is fairly common. In fact, many of the described risk factors such as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), smoking, steroid use, and male gender may actually represent surrogate measures of emphysema severity. The relevance of these data to the ARDS setting, where underlying emphysema is rare, is therefore unclear. No studies, to our knowledge, have identified risk factors for this complication in ARDS. Thus, the goal of this study was to identify predictors of persistent air leak after open lung biopsy in patients with ARDS.

Material and Methods

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously described [2]. Briefly, a retrospective review was per- formed of all patients with ARDS undergoing surgical lung biopsy at the Massachusetts General Hospital, a tertiary care referral center, over a 12-year period from January 1, 1989 to December 31, 2000. Approval for this study was obtained from the appropriate institutional review board. Individual consent was waived. Medical records of all patients with a discharge diagnosis of ARDS and a relevant procedure code were reviewed for potential inclusion. Patients had to meet the AECC definition for ARDS at the time of biopsy. From the previously described cohort of 57 patients, four were excluded from the analysis. Three were not intubated preoperatively, and thus ventilator data were not available. One additional patient died six hours postoperatively, and it was impossible to determine whether a persistent air leak would have developed [2]. For the remaining patients, an air leak was a priori defined as persistent if it was present on postoperative day 7 or at the time of death if the patient did not survive to day 7 [9]. Preoperative ventilator settings were those last recorded by the respiratory therapist prior to surgery. Postoperative ventilator settings were those reported closest to 24 hours after onset of surgery. Peak airway pressure was defined as the maximal pressure delivered by the ventilator, no matter the mode of ventilation. Lung biopsy was done in the intensive care unit (ICU) or in the operating room, by a mini-thoracotomy or thoracoscopy (based on the patients’ ability to tolerate single lung ventilation) at the discretion of the thoracic surgeon.

For thoracotomy, a standard anterolateral or lateral muscle sparing incision was made. For thoracoscopy, patients were reintubated with a double lumen endotracheal tube. Two intercostal access sites were chosen in standard orientation. Inspection with a thoracoscope was performed, and manipulation was performed using small Duval forceps. For both procedures, after inspection of the lung, biopsy specimens were taken from at least two different areas representing the spectrum of the disease process, usually in dependent areas of the middle lobe (or lingula) and the lower lobe. Biopsies were performed with serial application of a stapler. Staple lines were inspected for bleeding and air leak. In addition, if the patient was able to tolerate lateral decubitus positioning, the site was also tested for air leak by submersion in warm saline. Glues and sealants were not used. One or two chest tubes were inserted before closing the chest at the discretion of the surgeon. Chest tubes were placed to suction at −20 cm H2O for 48 hours, and were placed to water seal after that point if there was no evidence of air leak. Postoperative evaluation for air leak occurred at least once daily. No major changes in surgical technique or postoperative care at our institution occurred over the course of the study except for the introduction in mid- 1995 of a surgical stapling device (Endo-GIA stapler, U.S. Surgical, Norwalk, CT) designed for endoscopic use for the resection of lung parenchyma.

Potential predictors of air leak considered in this study included baseline characteristics (age, gender, chronic steroid use, immune status, etc), ventilator strategy (tidal volumes, peak pressures, positive end expiratory pressure [PEEP], mode of ventilation), surgical technique (thoracotomy versus thoracoscopy, use of endoscopic stapler), and underlying diagnosis (infection, diffuse alveolar damage).

Summary data are presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed variables and as median and range otherwise. Differences between groups were compared with the Fisher exact test for dichotomous variables, the Student t test for continuous variables with a normal distribution, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed variables. Pearson correlations were used to assess associations between continuous variables. Logistic regression was performed to identify risk factors for persistent air leak and death in univariate analyses. Variables with p less than 0.1 in univariate analysis were then used as independent variables in a stepwise logistic regression analysis, with a p less than 0.05 criterion for retention of variables in the final model. The multivariate procedure was validated by bootstrap bagging with 1,000 samples as has been previously described [10]. In the bootstrap procedure, repeated samples were generated with replacement from the original set of observations. For each sample, stepwise logistic regression was performed entering the predictors with p less than 0.1 at univariate analysis. The stability of the final stepwise model can be assessed by identifying the variables that enter most frequently in the repeated bootstrap models and comparing with the variables in the final stepwise model. If the final stepwise model variables occur in a majority (>50%) of the bootstrap models, the original final stepwise regression model can be judged stable. All analyses were performed using SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 53 patients, who met the inclusion criteria, were identified. Baseline demographic and preoperative characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean (±SD) age of the patients was 52 (±17.6) years. Over half were previous or current smokers, and approximately one third were immunosuppressed. The cohort all had severe respiratory failure meeting the strict AECC criteria for ARDS with a mean (±SD) partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (Pao2/Fio2) ratio of 147 (±63) mm Hg. Because of the high illness severity, only 6 of the 53 patients (11.3%) underwent thoracoscopy. Postoperative ventilatory characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Preoperative Characteristics

| Characteristic | No Air Leak (n = 37) | Air Leak (n = 16) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 53.3 ± 16.2 | 49.3 ± 20.9 | 0.45 |

| Male gender | 56.8 | 75.0 | 0.24 |

| History of smoking | 56.8 | 43.8 | 0.55 |

| Immunosuppressed | 29.7 | 37.5 | 0.75 |

| Diabetes | 10.8 | 12.5 | 1.00 |

| Any preoperative steroids | 48.7 | 37.5 | 0.55 |

| Days from intubation to biopsya | 4 (0–25) | 2.5 (0–13) | 0.05 |

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 10.1 ± 4.3 | 10.5 ± 3.9 | 0.71 |

| Peak airway pressure (cm H2O) | 32.1 ± 9.2 | 42.8 ± 10.8 | 0.0005 |

| Pao2/Fio2 ratio (mm Hg) | 165.9 ± 60.0b | 105.1 ± 48.3 | 0.0008 |

| Tidal volume (mL) | 702.8 ± 258.2 | 945.3 ±171.3 | 0.001 |

| Volume-cycled ventilator mode | 46.0 | 81.3 | 0.03 |

| Presence of DAD on biopsy | 35.1 | 62.5 | 0.08 |

| Positive culture on pathologic specimen | 18.9 | 12.5 | 0.71 |

| VATS | 16.2 | 0.0 | 0.16 |

| Endoscopic stapler | 56.8 | 12.5 | 0.003 |

Data presented as median (range).

Excluding one patient without a preoperative arterial blood gas.

Data presented are percentages or mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

DAD = diffuse alveolar damage; Pao2/Fio2 = partial pressure of oxygen, arterial to fraction of inspired oxygen; PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure; VATS = video- assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Table 2.

Postoperative Characteristics

| Characteristic | No Air Leak (n = 37) |

Air Leak (n = 16) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steroids | 75.7 | 87.5 | 0.47 |

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 10.0 ± 4.3a | 13.5 ± 4.5 | 0.01 |

| Peak airway pressure (cm H2O) | 32.6 ± 11.2a | 43.6 ± 13.9 | 0.003 |

| Pao2/Fio2 ratio (mm Hg) | 159.1 ± 62.4 | 118.0 ± 72.0 | 0.04 |

| Tidal volume (mL) | 683.6 ± 261.8a | 922.8 ± 223.6 | 0.003 |

| Volume cycled ventilator mode | 43.2a | 75.0 | 0.04 |

Excluding one patient extubated postoperatively.

Data presented are percentages or mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

DAD = diffuse alveolar damage; Pao2/Fio2 = partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio; PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure.

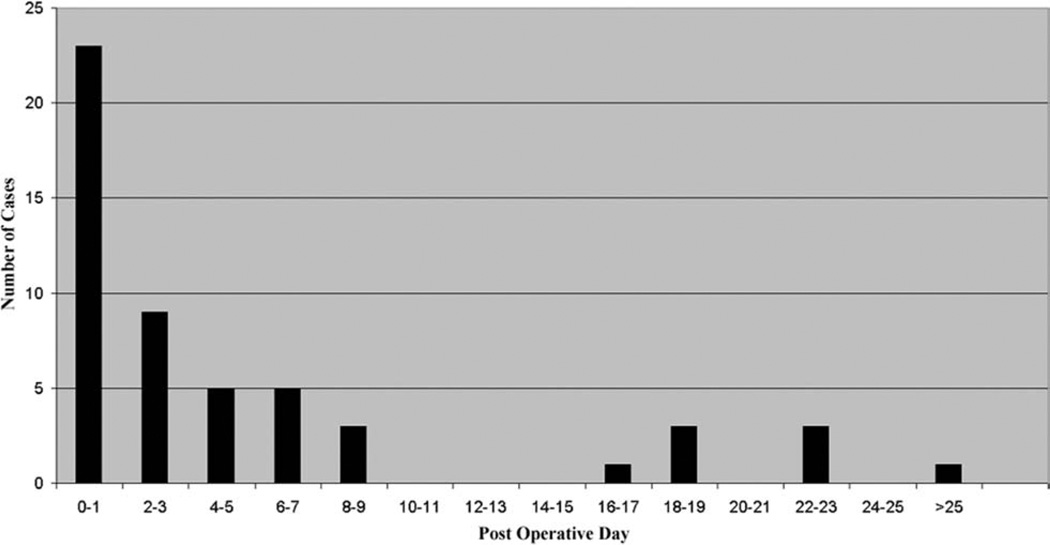

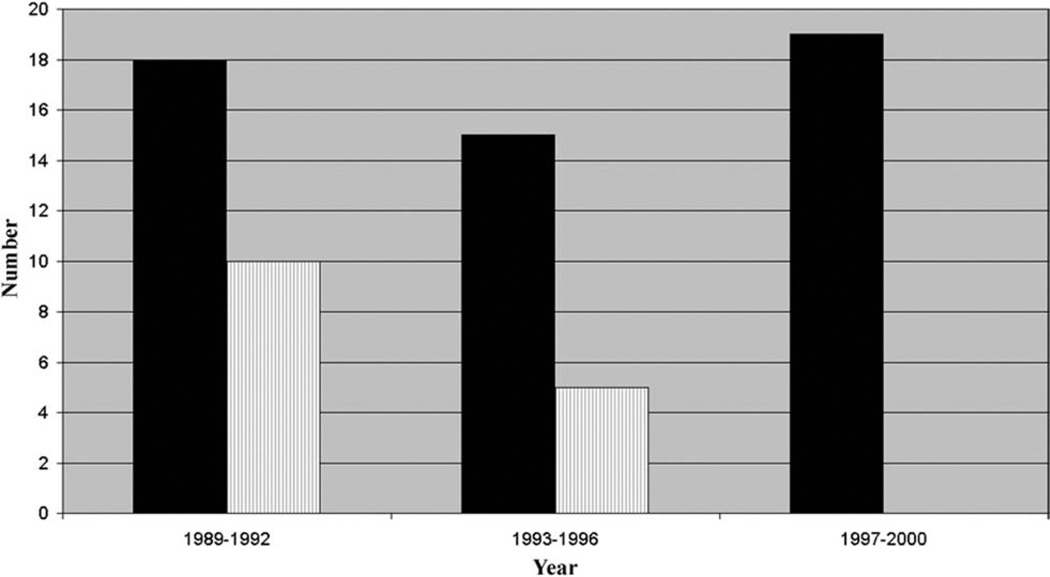

The median duration of air leak was 2 days (range, 0 to 48 days). Sixteen patients (30.2%) were defined as having a persistent air leak (Fig 1). Over the 12-year course of this study, the risk of prolonged air leak fell from 56% in 1989 to 1992, to 33% in 1993 to 1996, to 0% in 1997 to 2000 (Fig 2). In general, predictors of air leak in the setting of lung resection for malignancy (age, steroid use, and male gender) were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1). Ventilatory parameters, however, did differ between those with and without prolonged air leak. The strongest association with persistent air leak was a higher preoperative peak airway pressure with a mean peak pressure in those with air leak of 42.8 cm H2O as compared with 32.1 cm H2O in those without persistent air leak (p = 0.0005). Other preoperative ventilator variables that were significantly associated with air leak were higher tidal volumes (945 mL vs 703 mL, p = 0.001) and the use of volume cycled ventilation (81% vs 46%, p = 0.03). In addition, those with air leak had an increased severity of lung injury as assessed by a lower Pao2/Fio2 ratio (105 mm Hg vs 166 mm Hg, p = 0.0008). The type of surgical procedure (thoracoscopy versus thoracotomy) was not predictive of prolonged air leak but use of an endoscopic stapler was associated with a reduced risk of this complication. The stapler was used in only 12.5% of patients who had a persistent air leak versus 56.8% of those who did not develop this problem (p = 0.003). Of the postoperative ventilatory parameters, higher peak airway pressures, tidal volume, PEEP, PaO2/Fio2 ratio, and volume cycled ventilation were significantly associated with air leak (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Days to cessation of air leak.

Fig. 2.

Biopsies (black bars) and air leaks (vertical lined bars) by year.

Therapeutic strategies associated preoperatively with a lowered risk of prolonged air leak were evaluated by logistic regression (Table 3). For every 5 cm H2O reduction in peak airway pressure, the risk of persistent air leak was reduced by 42% (95% confidence interval [CI] [17% to 60%]). Similarly, every 100 mL reduction in tidal volume resulted in a risk reduction of 35% (95% CI [12% to 51%]). The use of pressure-cycled ventilation had an 80% (95% CI [20% to 95%]) reduction in risk compared with volume-cycled ventilation and use of the endoscopic stapling device was associated with an 89% (95% CI [45% to 98%]) reduction. In a stepwise regression model, only preoperative peak airway pressure remained a significant, independent predictor of air leak. The bootstrap analysis confirmed peak airway pressure was the only consistent predictor of prolonged air leak appearing in 53% of models.

Table 3.

Predictors of Air Leak

| Predictor | Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak airway pressure (per 5 cm H2O decrease) | 0.58 | [0.40–0.83] | 0.003 |

| Tidal volume (per 100 mL decrease) | 0.65 | [0.49–0.88] | 0.005 |

| Use of endoscopic stapler | 0.11 | [0.02–0.55] | 0.007 |

| Pressure cycled ventilator mode | 0.20 | [0.05–0.80] | 0.02 |

Ventilator settings are based on preoperative values.

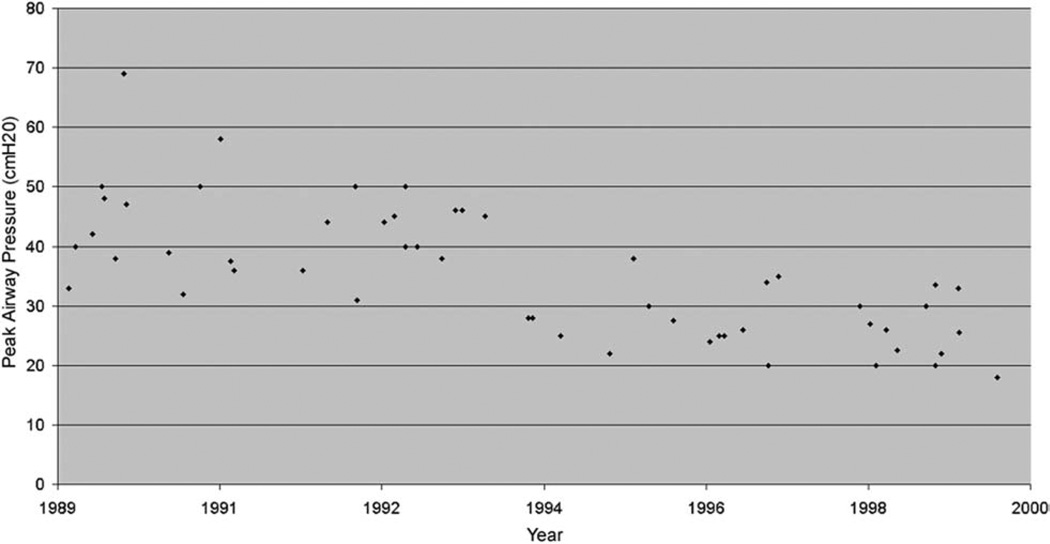

In order to understand better the drop in air leak risk over time, we plotted the preoperative peak airway pressure as a function of date of biopsy (Fig 3). We found a significant correlation (r = −0.72; p < 0.0001) between these two variables such that for every additional year of the study, the peak airway pressure fell by a mean (standard error) of 1.89 (0.26) cm H2O. After including peak airway pressure in multivariate modeling, the relationship between date of biopsy and risk of prolonged air leak was no longer significant. No significant correlation between preoperative peak pressure and a measure of lung injury severity (Pao2/Fio2) was found (r = −0.26, p = not significant) suggesting the association between high peak pressures and increased risk of persistent air leak was not due to confounding by lung injury severity.

Fig. 3.

Peak inspiratory pressures by date (each point represents a single case).

Analysis for whether persistent air leak was associated with death was complicated by the inclusion of those who had died in the initial 7 days with an air leak. For the subgroup that had survived until day 7 (n = 44) a trend for greater mortality in those with a persistent air leak was found (67% vs 36%); however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Sensitivity analyses were performed considering the five patients who died with an air leak before day 7 as not having an air leak and then excluding them completely. No substantial difference in our findings was observed. A higher peak ventilatory pressure was significantly associated with an increased risk of persistent air leak [data not shown].

Comment

Our incidence of persistent air leaks in open lung biopsy for ARDS was 30.2%. This value is higher than the 3% to 22% reported in previous studies of biopsy of diffuse lung disease [3–7], and likely due to several factors. One factor is our assumption that air leaks would have persisted in those patients who died before day 7. Another factor is that the illness severity in our patients was high, as reflected by the low Pao2/Fio2 ratio and the requirement for mechanical ventilation. Our data show that the risk of persistent air leaks is significantly associated with higher preoperative ventilatory settings. One interpretation of these data is that limiting airway pressures and volumes may prevent the development of persistent air leak after lung biopsy in ARDS.

Several risk factors have been identified for air leak in more routine lung resection. These include age; male gender; low forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FEV1/ FVC); steroid use; concurrent infection; diabetes; malnutrition; presence of pleural adhesions; upper versus lower lobectomy; and individual surgeon [8, 10–12]. While the presence of diffuse lung disease has not been prospectively studied, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing lung volume reduction surgery the presence of additional pathology appears to increase the risk for persistent air leak [13]. We assessed several of these previously determined risk factors (age, gender, smoking, concurrent infection, diabetes) and found no significant correlation with air leak risk. Several operative techniques, such as buttressing the staple line, glues and sealants, and pleural tents, as well as postoperative chest tube management have been explored as solutions to prevent or control air leaks, with variable success [11, 14–19]. During the time period of our study, the surgical stapler at our institution was changed to a disposable device that had better staple formation on thicker tissue and placed an additional row of staples to secure the lung. Use of this stapler was associated with reduced risk of persistent air leak. We were unable to evaluate other aspects of operative and postoperative care, including chest tube management, as they did not vary across the cohort.

Controlling airway pressures has been recommended both for the management and prevention of persistent air leaks [20, 21]. In surgically created bronchopleural fistulae in animals, the rate of gas flow was primarily influenced by mean airway pressure [22]; thus, presumably reducing the mean airway pressures would reduce flow through the fistula and lead to faster resolution. However, more specific data are lacking. While high frequency ventilation has been used in management of bronchopleural fistulas, we are not aware of any data concerning the effect of ventilator mode (volume-cycled versus pressure-cycled) on risk of persistent air leak. We found a reduced risk associated with the use of pressure-cycled ventilation. This may be due to a better ability to ensure against brief rises in airway pressure with this modality.

Although the etiology differs, barotrauma resulting in persistent air leaks can be seen in the setting of ARDS. This complication may increase the duration of mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and hospital mortality [23]. The striking difference in the incidence of barotrauma in recent trials compared with those reported 10 to 15 years ago lends support to the hypothesis that higher airway pressure is a major contributor [24]. For example, Amato and colleagues [25] found a marked reduction in pneumothorax risk using a lung protective strategy with lower tidal volumes and ventilatory pressures. More recently, a review of ARDS clinical trials found lower plateau pressures (below 35 cm H2O) were associated with a reduction in risk of barotrauma [26].

While our data support a correlation between reduction in ventilator pressures and risk of persistent air leak, there are several limitations that should be noted. First, the pressure across the lung parenchyma (the transpulmonary or transalveolar pressure) more accurately reflects the potentially injurious distending pressure on the lung than the airway opening pressures measured and applied by the ventilator. While true transpulmonary pressures are difficult to measure without additional equipment, plateau pressure is likely a more reliable surrogate than peak pressure; however, none of these data were available for our study. Although we acknowledge this limitation, we would argue that the airway opening pressure is a more practical variable for the treating clinician to monitor and (or) modify.

Second, we cannot discount the possibility that a lower peak airway pressure in our population was simply a reflection of less diseased lung. However, high peak airway pressures were more strongly associated with prolonged air leak than other measures of lung injury severity such as Pao2/Fio2 ratio. The lack of correlation between peak pressure and Pao2/Fio2 ratio further suggests that peak pressure was an independent variable determined by the treating clinician rather than a dependent variable of lung injury severity.

A notable finding of our study was the large drop in the risk of air leak over the 12-year period of this study. Our data suggest the fall in peak pressures used to ventilate patients during this time explains this temporal drop in risk. However, other changes may also explain this finding. For example, the endoscopic stapler was introduced into general use at our institution in mid-1995. Other unmeasured aspects of care may also have changed over time; aspects such as better nutritional support, development of more effective antibiotics, and improvements in overall ICU care. Because of the observational nature of this study, we cannot definitively establish whether minimizing airway pressures in this setting leads to improvements in clinical outcome.

While the results of the ARDSNet study advocating lower tidal volumes and ventilatory pressures have generally been accepted, aspects of the study have been questioned [27] and ventilation with low tidal volumes is still not routinely applied [28]. Despite the limitations in our study, the strong correlation between inspiratory pressures, tidal volumes, and risk of prolonged air leak lends support to the notion that reducing airway pressures and tidal volume may reduce the risk of postoperative air leak. Further research to test this hypothesis is merited. Whatever the etiology, the risk of morbidity from open lung biopsy in ARDS at our institution has dropped substantially since the 1980s. In light of these improvements, more frequent use of this diagnostic modality should be considered. Finally, the lack of correlation between corticosteroid administration and persistence of air leak should allay fears about employing this treatment in those cases where biopsy results support the use of these agents.

References

- 1.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SR, Karmpaliotis D, Ayas NT, et al. The role of open-lung biopsy in ARDS. Chest. 2004;125:197–202. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flabouris A, Myburgh J. The utility of open lung biopsy in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1999;115:811–817. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papazian L, Thomas P, Bregeon F, et al. Open-lung biopsy in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:935–944. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meduri GU, Chinn AJ, Leeper KV, et al. Corticosteroid rescue treatment of progressive fibroproliferation in late ARDS. Patterns of response and predictors of outcome. Chest. 1994;105:1516–1527. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.5.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner DO, Warner MA, Divertie MB. Open lung biopsy in patients with diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and acute respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:90–94. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canver CC, Mentzer RM., Jr The role of open lung biopsy in early and late survival of ventilator-dependent patients with diffuse idiopathic lung disease. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1994;35:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loran DB, Woodside KJ, Cerfolio RJ, Zwischenberger JB. Predictors of alveolar air leaks. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2002;12:477–488. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3359(02)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adebonojo SA. How prolonged is “prolonged air leak”? Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:549–550. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)93429-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunelli A, Monteverde M, Borri A, et al. Predictors of prolonged air leak after pulmonary lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerfolio RJ, Bass CS, Pask AH, Katholi CR. Predictors and treatment of persistent air leaks. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1727–1730. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okereke I, Murthy SC, Alster JM, Blackstone EH, Rice TW. Characterization and importance of air leak after lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller CA, Naunheim KS, Osterloh J, et al. Histopathologic diagnosis made in lung tissue resected from patients with severe emphysema undergoing lung volume reduction surgery. Chest. 1997;111:941–947. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunelli A, Monteverde M, Borri A, et al. Comparison of water seal and suction after pulmonary lobectomy: a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1932–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerfolio RJ, Bass C, Katholi CR. Prospective randomized trial compares suction versus water seal for air leaks. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1613–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice TW, Okereke IC, Blackstone EH. Persistent air-leak following pulmonary resection. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2002;12:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3359(02)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller CA. Lasers, staples, bovine pericardium, talc, glue and. . .suction cylinders? Tools of the trade to avoid air leaks in lung volume reduction surgery. Chest. 2004;125:361–363. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toloza EM, Harpole DH., Jr Intraoperative techniques to prevent air leaks. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2002;12:489–505. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3359(02)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerfolio RJ, Tummala RP, Holman WL, et al. A prospective algorithm for the management of air leaks after pulmonary resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1726–1731. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu EH, Gillbe CE, Watson AC. Anaesthetic management of patients undergoing lung volume reduction surgery for treatment of severe emphysema. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27:459–463. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9902700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierson DJ. Management of bronchopleural fistula in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. New Horiz. 1993;1:512–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh MC, Carlo WA. Determinants of gas flow through a bronchopleural fistula. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:1591–1596. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.4.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anzueto A, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, et al. Incidence, risk factors and outcome of barotrauma in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:612–619. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricard JD. Barotrauma during mechanical ventilation: why aren’t we seeing any more? Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:533–535. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:347–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boussarsar M, Thierry G, Jaber S, et al. Relationship between ventilatory settings and barotrauma in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:406–413. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eichacker PQ, Gerstenberger EP, Banks SM, Cui X, Natanson C. Meta-analysis of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome trials testing low tidal volumes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1510–1514. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-956OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinert CR, Gross CR, Marinelli WA. Impact of randomized trial results on acute lung injury ventilator therapy in teaching hospitals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1304–1309. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-478OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]