Abstract

Oxidative stress, caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), is a major contributor to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-associated neoplasia. We mimicked ROS exposure of the epithelium in IBD using non-tumour human colonic epithelial cells (HCEC) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). A population of HCEC survived H2O2-induced oxidative stress via JNK-dependent cell cycle arrests. Caspases, p21WAF1 and γ-H2AX were identified as JNK-regulated proteins. Up-regulation of caspases was linked to cell survival and not, as expected, to apoptosis. Inhibition using the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK caused up-regulation of γ-H2AX, a DNA-damage sensor, indicating its negative regulation via caspases. Cell cycle analysis revealed an accumulation of HCEC in the G1-phase as first response to oxidative stress and increased S-phase population and then apoptosis as second response following caspase inhibition. Thus, caspases execute a non-apoptotic function by promoting cells through G1- and S-phase by overriding the G1/S- and intra-S checkpoints despite DNA-damage. This led to the accumulation of cells in the G2/M-phase and decreased apoptosis. Caspases mediate survival of oxidatively damaged HCEC via γ-H2AX suppression, although its direct proteolytic inactivation was excluded. Conversely, we found that oxidative stress led to caspase-dependent proteolytic degradation of the DNA-damage checkpoint protein ATM that is upstream of γ-H2AX. As a consequence, undetected DNA-damage and increased proliferation were found in repeatedly H2O2-exposed HCEC. Such features have been associated with neoplastic transformation and appear here to be mediated by a non-apoptotic function of caspases. Overexpression of upstream p-JNK in active ulcerative colitis also suggests a potential importance of this pathway in vivo.

Keywords: hydrogen peroxide-associated colitis, DNA-damage checkpoints, non-apoptotic caspase function, JNK-dependent cell cycle arrests, inflammation, neoplastic transformation, ATM degradation, γ-H2AX

Introduction

The most compelling evidence in support of the causal relationship between inflammation and carcinogenesis is provided by ulcerative colitis (UC)-associated colorectal cancer (UC-CRC) and tumours arising as a consequence of Crohn's disease and hepatitis C infection. Indeed, inflammation is regarded as the seventh hallmark of cancer 1. Although it has been suggested that chronic inflammation and colonic injury can directly cause DNA alterations, it remains to be clarified whether inflammation alone without carcinogen exposure can result in tumour initiation 2. In this context, the role of ROS is of major importance 3, particularly as oxidative stress is one of the most important pathogenetic factors in UC-CRC 4, 5.

In a mouse model, cyclical exposure to dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) leads to the development of colitis through induction of epithelial apoptosis, a cellular feature that has also been reported in UC patients 6. However, much less is known about the function of cell cycle arrest in UC and whether arrest links reparative and uncontrolled proliferative response to inflammation. Based on in vitro studies, Araki and coworkers suggested that enhanced cell cycle promotion in DSS-induced colitis and UC patients occurs as a reaction following repair from colitis 7. It is well known that cells are provided with DNA-damage checkpoints to control cell cycle progression 8. Overcoming cell cycle control is a fundamental mechanism in the pathogenesis of human cancers. Cells that lack cell cycle control have selective growth advantages. Consequently, genetic changes such as p53 inactivation are important events at the beginning of the UC-carcinoma pathway. It is known that ROS are stress signals for the cell culminating in activation of MAPK's (Mitogen-activated protein kinases), proteins that also play a role in cell cycle checkpoint control 8. Dysregulation of MAPK's and their regulated proteins may, therefore, switch the cellular signalling pathways from cell cycle arrest to enhanced proliferation.

Caspases are cysteinyl-proteases that mediate apoptosis and inflammation via proteolytic cleavage of cellular substrates after a specific aspartate residue 9. Novel studies have also shown that caspases have a non-apoptotic function 10–13, including processing of cytokines during inflammation, proliferation of T lymphocytes and terminal differentiation of keratinocytes. In addition, death receptors such as TRAIL-R1/DR4 (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 1) also execute non-apoptotic functions as they can activate the non-apoptotic NFκB- or JNK pathways via the ligand TRAIL 14. Muhlenbeck et al. observed caspase-dependent JNK activation, but caspase-independent apoptosis 15. This suggests that the JNK–caspase pathway also unravels a non-apoptotic function of TRAIL.

Herbst et al. have shown that the non-tumourigenic human colonic epithelial cell line HCEC 16–21 is suitable to study carcinogen-induced malignant cell transformation 22. Consequently, HCEC is an appropriate cell line to investigate how ROS may act as the link between inflammation and tumourigenesis.

In this study, we aimed at identifying a function of cell cycle arrest in our cellular model of H2O2-associated colitis. We tried to answer the question of whether arrest may link reparative and uncontrolled proliferative response. We showed that ROS activates the JNK pathway resulting in S- and G2/M arrest. Caspases, p21WAF1 and γ-H2AX were identified as JNK-regulated proteins. Importantly, caspases executed a non-apoptotic function as they mediated survival of oxidatively damaged HCEC via suppression of γ-H2AX. This made the G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint ineffective. A population of cells thereby survived. A direct inactivation of γ-H2AX through caspases was excluded. We showed that oxidative stress led to caspase-mediated proteolytic degradation of ATM that is upstream of γ-H2AX. Our findings suggest that delayed arrest in the subsequent cell cycle phases via checkpoint override led to survival mediated by a targeting of the caspases by the MAPK/JNK-signalling pathway. We speculate that this survival mechanism during oxidative stress is linked to enhanced proliferation of repeatedly H2O2-exposed cells in recovery from oxidative stress. The resultant increased proliferation and undetected DNA-damage, both hallmarks of transformation, may serve to initiate tumourigenesis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

For the development of HCEC, a retroviral vector was used to transfer the SV40 large T antigen cDNA into primary HCEC isolated from a non-tumour carrying donor 16. Therefore, HCEC has characteristics consistent with colon, epithelial and non-transformed origin (expression of colon-specific dipeptidyl-peptidase IV, epithelial-specific cytokeratins and no expression of a mutant p53, APC or CEA gene). HCEC cells generated by Nestec Ltd (Nestlé Research Center Lausanne, Switzerland) were obtained from Professor P. Steinberg (Institute of Food Toxicology and Analytical Chemistry, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Germany) and were cultured on collagen-coated plates (1:2000, Becton-Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) in basal HCEC cell culture medium (PAN, Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany) according to Blum et al. 16 at 37°C and 5% CO2. The basal HCEC medium was supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (PAA, Velizy-Villacoublay, France), 30 μg/ml vitamin C (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), 100 nM retinoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 nM dexamethason (Sigma-Aldrich) and 38 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) prior to use. In this study, we treated HCEC with pathophysiological H2O2 concentration (patH2O2 = 200 μM) as released by macrophages during inflammation 23 to mimic the in vivo setting of acute inflammation in colitis. Cells were collected after 24, 48 and 72 hrs after treatment. We generated three altered HCEC cell cultures (HCECpatH2O2C1-C3) by three repeated treatments of HCEC with H2O2 and two recovery phases in between, thus simulating chronic inflammation via ROS.

Inhibition studies

JNK kinase activity was inhibited using the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Enzo, Lörrach, Germany) at a concentration of 50 μM. The effective inhibition of JNK was ensured through missing phosphorylation of the transcription factor c-jun at serine residues 63 and 73. We inhibited all caspases using the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (50 μM, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Cell cycle analysis

One day before treatment, cells were seeded into Petri dishes (90 mm diameter) at a density of 5.0 × 105 cells per dish. For analysis of cell cycle distribution following JNK or caspase inhibition, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2.0 × 105 cells per well. Cell cycle analysis was performed as described previously 24. Distribution of cell cycle phases with different DNA contents was determined using a flow cytometer (Calibur, Becton-Dickinson). Cell cycle distribution was analysed, and the percentage of cells in cell debris, G1-, S- and G2/M-phase of the cell cycle was determined using ModFit software, version LT3.2 (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA).

Subcellular fractionation

The subcellular fractionation of HCEC and H2O2-treated HCEC was performed with the Subcellular Protein Fractionation Kit from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One to three million cells were separated stepwise, and cytoplasmic, membrane, nuclear soluble, chromatin-bound and cytoskeletal protein extracts were prepared. The extracts were analysed further by immunoblotting.

Immunoblot analysis

Proteins were prepared as described previously 25. For immunoblot analysis, the following antibodies were used: caspase 3, caspase 8, caspase 9, JNK, p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p-c-jun (Ser63), p-c-jun (Ser73), ATM, cyclin D2, c-fos, p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), HSP90 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); p21WAF1 (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany); p-H2AX (Ser139, γ-H2AX, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA); β-actin, β-catenin (Sigma-Aldrich); TRAIL-R1/DR4, c-myc (Abcam, Cambridge, UK); H2AX (Upstate, Billerica, MA, USA); CDK6 (Acris, Antibodies, Herford, Germany); GAPDH and H3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); and Sp1 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, Colorado, USA). Densitometric analysis of data was performed with the GeneTools Software from Syngene (Cambridge, UK). Fold induction (ratio protein/β-actin) was calculated using the loading control β-actin.

Proliferation assay

Human colonic epithelial cells and HCECpatH2O2C1-C3 were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. Cells were collected and counted using a particle count and size analyser (COULTER) after 7 days. The cell numbers were determined in quadruplicate.

Comet assay

To estimate DNA-damage, we performed the CometAssay (Trevigene Gaithersburg, MD, USA) as described previously 24. Evaluation was performed with a fluorescence microscope (Axioplan2, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY, USA) equipped with appropriate filter sets. Images were acquired using Isis V 3.4.0 software.

Phalloidin staining

To characterize filopodia formation of HCEC, cells were cultured in a monolayer on collagen-coated coverslips (Becton-Dickinson) followed by formalin fixation (3.5%, Roth) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized (0.2% TritonX 100, Roth), and non-specific binding was blocked (1% BSA, Roth). F-actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 488 Phallotoxin for 30 min at room temperature (1:200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Slides were mounted and nuclei stained with DAPI-mounting medium (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Evaluation was performed with the fluorescence microscope (Axioplan2, ZEISS) Isis V 3.4.0 software.

Human cytokine multiplex assay

To measure cytokine release into the supernatant of HCEC, human multiplex cytokine ELISA (Signosis, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used. Therefore, the supernatants of HCEC treated with H2O2 and DMSO, H2O2 and SP600125 or Z-VAD-FMK and those of untreated controls were harvested after 72 hrs. Quantitative analyses of interleukins-6, 8 and 13 (Il-6, Il-8, Il-13) and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

The Department of Pathology, Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Germany provided us with biopsies of intestinal mucosa taken from the regular material entry. The specimens used were taken from the terminal ileum, coecum, colon ascendens, colon transversum, colon descendens, colon sigmoideum and the rectum. So far, one case of UC with high inflammatory activity, two cases of UC in complete remission and three cases of healthy mucosa have been observed. The sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded colitis specimens or corresponding healthy cases (2.0 μm thick) were mounted on glass slides and dried overnight. The slides were incubated with affinity-purified rabbit antibody against p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), (Cell Signaling) diluted 1:50 for 30 min at room temperature, after treatment with 3% H2O2 for 15 min. The reactions were visualized by DAB detection. The slides were counterstained with haematoxylin and cover slipped after embedding in mounting medium.

Statistical analysis of data

Student's t-test was used for data analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Oxidative stress led to S- and G2/M arrest via JNK

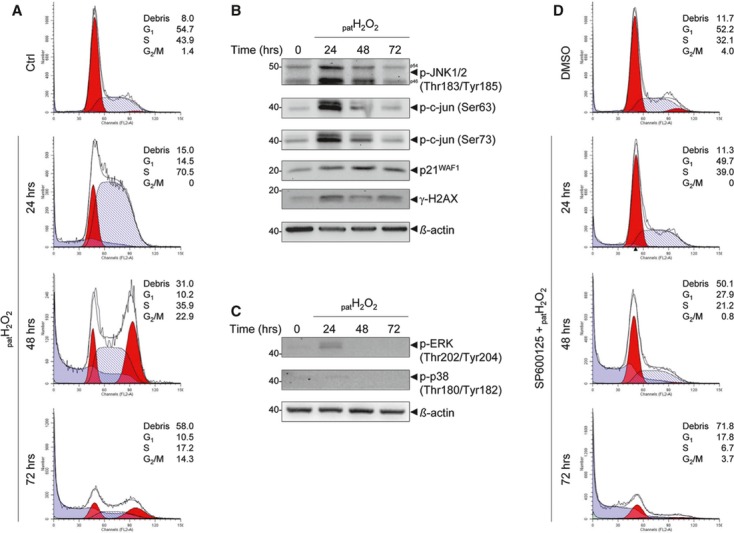

Hydrogen peroxide treatment of HCEC caused activation of DNA-damage checkpoints, as S cell cycle arrest was observed after 24 hrs and G2/M cell cycle arrest after 48 and 72 hrs (Fig. 1A). At the same time, there was prominent activation of JNK signalling (Fig. 1B), with increased levels of p-JNK and p-c-jun. In addition, up-regulation of p21WAF1 and γ-H2AX was detected. Only marginal activation of the other MAPK's p38 and ERK was seen (Fig. 1C). To identify whether the observed arrests are JNK-dependent, the effects of JNK inhibition using SP600125 were analysed (Fig. 1D). After JNK inhibition, H2O2 nearly completely abolished S arrest after 24 hrs and did not result in cell cycle arrests, but led exclusively to apoptosis after 48 and 72 hrs (Fig. 1D). As the JNK inhibitor was able to rescue S- and G2/M arrest, the activation of DNA-damage checkpoints was JNK-dependent. Taking into account that cytokines play a pivotal role in epithelial damage in UC 26, release of several cytokines from H2O2-stressed HCEC was determined using multiplex assay (Figure S1). We observed H2O2-dependent induction of Il–13 and TGFβ release. Moreover, Il-6 release and Il-8 release were not significantly affected following H2O2 treatment.

Fig. 1.

H2O2 treatment activates DNA-damage checkpoints through the JNK pathway. (A) Cell cycle analysis of H2O2-treated HCEC showed S arrest after 24 hrs, G2/M arrest after 48 and 72 hrs and apoptosis after 72 hrs. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Activation of the JNK pathway with p-JNK and p-c-jun (Ser63/Ser73) and up-regulation of p21WAF1. (C) H2O2 did not lead to significant activation of the MAPK's p38 and ERK in HCEC. (D) Abrogation of cell cycle arrest following JNK inhibition after 24 to 72 hrs.

Caspases are JNK-regulated proteins and mediate survival of HCEC following oxidative stress

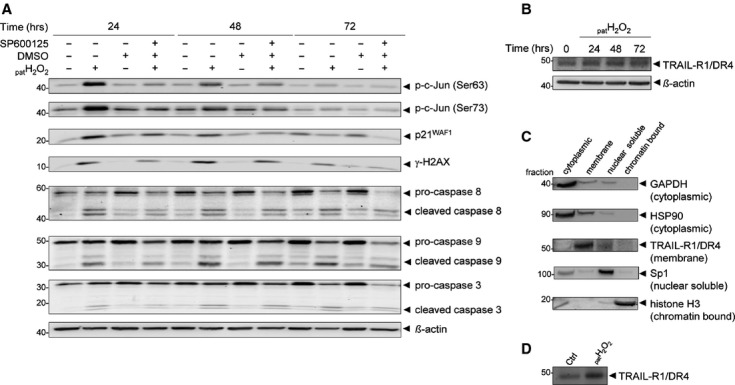

As shown, ROS induced JNK-dependent arrests in HCEC (Fig. 1). In addition, we would like to point out that we observed apoptosis (cell debris: 58% after 72 hrs, Fig. 1A). We detected increased expression of the effector caspase 3 after 24 hrs, and accumulation of active caspase 3 at all three time-points (Figure S2A). However, a broader caspase cleavage was expected to explain the high extent of apoptosis (Fig. 1A). Thus, a crucial involvement of caspases in apoptosis was excluded, and we hypothesized a role of caspases in cellular survival. We found increased expression of caspase 8 and 9 compared with the control 24 hrs after H2O2 (Fig. 2A), also suggesting induction of their expression. Moreover, we detected an increase in the levels of cleaved caspases 8 and 9 at all time-points in response to H2O2 (Fig. 2A), which is accompanied by a reduction in the respective uncleaved caspase at 72 hrs as would be expected for cytoplasmic proteins activated in situ. To identify JNK-regulated proteins through which JNK influences the cell cycle, we performed immunoblotting analysis following JNK inhibition (Fig. 2A). Proteins were classified as JNK-regulated proteins mediating survival based on down-regulation following JNK inhibition and H2O2 treatment compared with H2O2 treatment alone. We found JNK-dependent induction of p21WAF1 and γ-H2AX 24 hrs and 48 hrs after H2O2 treatment respectively. Therefore, we identified p21WAF1 and γ-H2AX as JNK-regulated proteins. Moreover, caspase 3, 8 and 9 were down-regulated 24, 48 and 72 hrs, respectively, after JNK inhibition compared with H2O2. The combined control treatment of H2O2 and DMSO allocated the observed caspases down-regulation to the JNK inhibitor and not to the solvent (Figure S2B). Thus, we identified caspases 3, 8 and 9 as JNK-regulated proteins that mediate cellular survival. As we also detected decreased cleaved caspase fragments following JNK inhibition, we propose that proteolytic active caspases are involved in survival of HCEC. In addition, cell cycle analysis following JNK inhibition induced increased apoptosis after 72 hrs (cell debris: 72%, Fig. 1D), but no increase in cleaved pro-caspases 3, 8 and 9 (Fig. 2A), further suggesting a non-apoptotic function of caspases.

Fig. 2.

Identification of cellular JNK-regulated proteins in H2O2-exposed HCEC. (A) Immunoblot analysis following JNK inhibition by the JNK inhibitor SP600125 revealed p21WAF1, γ-H2AX, as well as caspases 3, 8 and 9 as cellular JNK-regulated proteins. The effective inhibition of JNK was ensured through missing phosphorylation of the transcription factor c-jun at serine residues 63 and 73. (B) Immunoblot analysis showed an overexpression of the death receptor TRAIL-R1/DR4 after H2O2. (C) Immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractionated cellular proteins of H2O2-treated HCEC. Each extract was analysed using specific antibodies against proteins from various cellular compartments, including cytoplasmic (GAPDH, HSP90), plasma membrane (TRAIL-R1/DR4), nuclear soluble (Sp1) and chromatin-bound (histone 3). (D) Analysis of the membrane extracts of HCEC and H2O2-exposed HCEC by immunoblotting showed accumulation of the TRAIL-R1/DR4 in H2O2-exposed cells.

In addition, we found overexpression of the death receptor TRAIL-R1/DR4 24 and 48 hrs after H2O2 (Fig. 2B), which could be the cause of a non-apoptotic JNK pathway induction by caspases. Analysis of the membrane fraction after subcellular fractionation of H2O2-treated HCEC clearly showed the accumulation of TRAIL-R1/DR4 compared with untreated cells (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the release of Il-6 and TGFβ from H2O2-treated HCEC is JNK-dependent, whereas that of Il-8 and Il-13 seems to be suppressed via JNK (Figure S1).

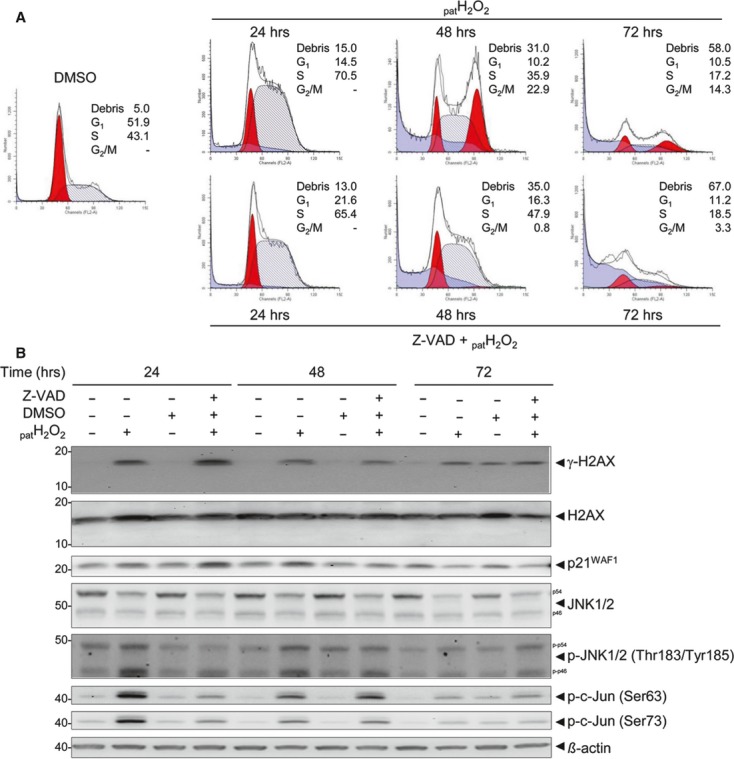

Non-apoptotic function of caspases through their role in cell cycle progression

Cell cycle analysis following caspase inhibition using Z-VAD-FMK showed (i) fewer cells in S- and more cells in the G1-phase after 24 hrs, (ii) fewer cells in G2/M- and more cells in the S-, G1-phase and debris after 48 hrs and (iii) fewer cells in G2/M-phase, but more cell debris after 72 hrs (Fig. 3A, G1: 14.5–21.6% after 24 hrs, 10.2–16.3% after 48 hrs; cell debris: 58.0–67.0% after 72 hrs). Thus, caspases seem to promote progression of cells through the G1- and S-phase by overriding the G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint, respectively. Consequently, caspases support cell survival by halting cells in the G2/M-phase after 72 hrs. Without proteolytic active caspases, a considerably higher percentage of cells underwent apoptosis (Fig. 3A, cell debris: 67.0% instead of 58.0%). It is apparent, therefore, that apoptosis is caspase-independent and that survival is dependent on proteolytic active caspases, generating cleaved caspase fragments (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 3.

Non-apoptotic function of caspases through their role in cell cycle regulation. (A) Cell cycle analysis of H2O2-treated HCEC following pre-incubation with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK showed more cells in the G1-phase (24 hrs) and fewer cells in the G2/M-phase, but more cells in the G1- and S-phase after 48 hrs. After 72 hrs, an apoptotic cell population (cell debris) increased significantly. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Immunoblot analysis of H2O2-exposed HCEC, pre-treated with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, revealed a caspase-mediated negative regulation of γ-H2AX and a positive regulation of the JNK pathway, including p-JNK and p-c-jun (Ser63/Ser73), after 24 hrs.

In summary, caspases promote cell cycle progression and hence survival following oxidative stress by assisting progression of cells through the G1- and S-phase.

Caspases suppress the DNA-damage checkpoint protein γ-H2AX during oxidative stress

To identify caspase-regulated proteins that could mediate progression of cells through G1- and S-phase by circumventing of DNA-damage checkpoint control, we performed immunoblot analysis following inhibition of caspase activity (Fig. 3B). As the DNA-damage sensor H2AX phosphorylated at serine 139 is known to play an important role in DNA-damage checkpoint control 27, we investigated its phosphorylation. γ-H2AX was increased significantly 24 hrs after H2O2- and Z-VAD-FMK treatment paralleled by down-regulation of unmodified H2AX, suggesting negative regulation of H2AX phosphorylation through caspase activity. Thus, caspases seem to mask DNA-damage by negative regulation of H2AX phosphorylation, and this may pave the way to neoplastic transformation as less DNA-repair proteins can be recruited to the site of damage. Caspase-dependent suppression of H2AX phosphorylation may therefore promote progression of cells through the G1- and S-phase. Hence, caspase activity seems to circumvent the G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint, thereby leading to increased survival despite the presence of DNA-damage. These fundamental factors are likely to contribute to neoplastic transformation of epithelial cells following H2O2 exposure. Indeed, we detected up-regulation of p21WAF1 following inhibition of caspase activity (Fig. 3B). This further supports the idea that sensitive DNA-damage recognition through γ-H2AX led to proper activation of the G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint with more cells in the G1- and S-phase through p21WAF1 up-regulation. As reported by Muhlenbeck et al., we also observed caspase-dependent activation of JNK as early response (after 24 hrs) 15, whereas we detected its suppression as second response (after 72 hrs), (Fig. 3B). In addition, the release of Il-13 and TGFβ from H2O2-treated HCEC was found to be caspase-dependent (Figure S1).

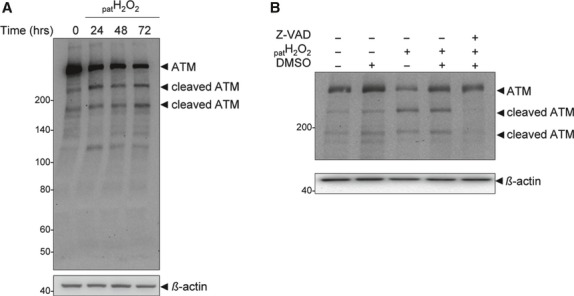

Caspase-dependent degradation of ATM

We next proved whether negative regulation of γ-H2AX proceeds via its proteolytic degradation. However, cleavage products of H2AX and γ-H2AX could not be observed (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we hypothesized that proteolytic inactivation of proteins occurred upstream of γ-H2AX and that these upstream proteins have a regulatory function by phosphorylating H2AX. Phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser 139 is preferentially catalysed by ATM. Hence, we considered the possibility of caspase-dependent degradation of the upstream molecule ATM. To test this, we first analysed whether oxidative stress may induce proteolytic cleavage of ATM. Immunoblot analysis revealed that ATM is cleaved 24, 48 and 72 hrs following H2O2 treatment (Fig. 4A). This cleavage was reversible 24 hrs after caspase inhibition (Fig. 4B), confirming caspase-dependent ATM degradation, which resulted in decreased levels of uncleaved ATM (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Caspase-dependent degradation of the ATM-kinase. (A) Immunoblot analysis showed H2O2-induced cleavage of ATM after 24, 48 and 72 hrs. (B) This cleavage was shown to be reversible after 24 hrs following caspase inhibition (Z-VAD-FMK).

Masked DNA-damage is linked to γ-H2AX suppression

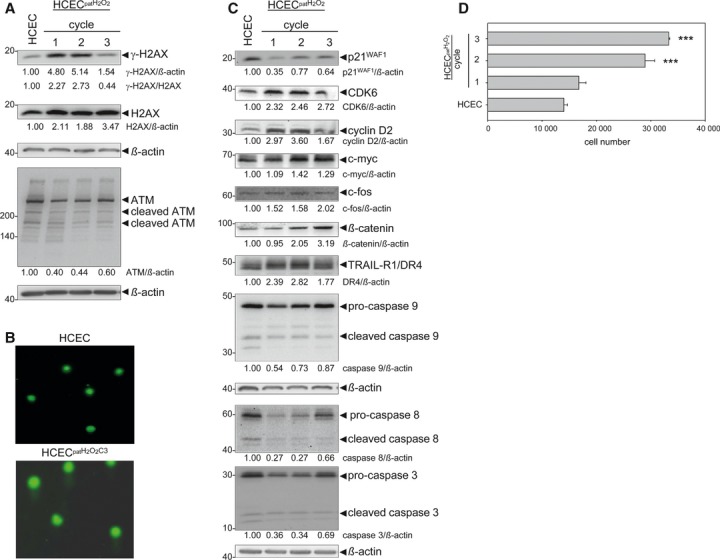

Chronic UC is characterized by recurrence-remission cycles with periods of mucosal ulceration accompanied by necrosis and regeneration of the colonic mucosa. Accordingly, we simulated the clinical course of IBD with its multiple exposure of colonic epithelial cells to ROS during flares by exposing HCEC to repeated H2O2 cycles (C1-3) with recovery phases in between exposures (altered HCECpatH2O2C1-C3). We then investigated γ-H2AX expression in the newly generated cell cultures, but detected only a marginal protein level in the third cycle, although the non-phosphorylated protein was markedly expressed (Fig. 5A, γ-H2AX : H2AX = 0.44). Hence, the ratio of γ-H2AX to H2AX is lower in HCECpatH2O2C3 than in control HCEC. Therefore, there is no significant DNA-damage signalled to the cell's repair mechanisms through γ-H2AX. Importantly, comet assay analysis revealed significantly damaged DNA of HCECpatH2O2C3 as indicated by enlarged nuclei, as well as comet tails, which are representative for DNA single- and double-stranded breaks (Fig. 5B). Thus, as it has been suggested, DNA-damage accumulates undetected by the cells because of the negative regulation of γ-H2AX.

Fig. 5.

Undetected DNA-damage is linked to γ-H2AX down-regulation. (A) Immunoblot analysis of altered HCECpatH2O2C3 showed a decreased ratio of γ-H2AX to H2AX, as well as a decreased ATM level in altered HCEC compared with the control. (B) Comet assay revealed damaged DNA of HCECpatH2O2C3 as enlarged nuclei and comet tails were detected. Untreated HCEC served as control. (C) Altered HCEC showed down-regulation of the negative cell cycle regulator p21WAF1 and up-regulation of the positive cell cycle regulators CDK6 and cyclin D2. Furthermore, an up-regulation of the oncogenic transcription factors c-myc and c-fos as well as of β-catenin and TRAIL-R1/DR4 was detected. Caspases 3, 8 and 9 were found to be down-regulated. (D) The repeated exposure of HCEC to H2O2 led to increased cell proliferation: after 7 days, the number of cells was higher in HCECpatH2O2C1 to HCECpatH2O2C3 compared with HCEC. Data indicate mean ± SEM and were obtained from four independent experiments. ***P < 0.001.

Masked DNA-damage is linked to increased proliferation

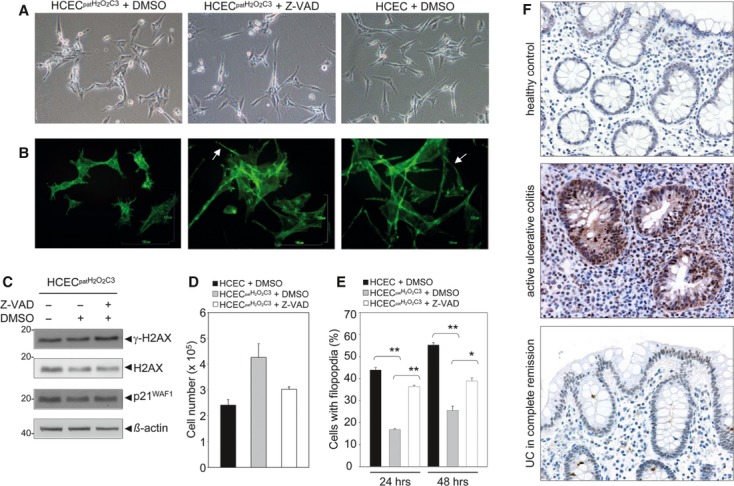

We next proved whether undetected DNA-damage is linked to increased proliferation. Indeed, we found increased proliferation of HCECpatH2O2C1-C3 (Fig. 5D). In this context, we investigated the expression of cell cycle regulators in the newly generated cell cultures. In support of our hypothesis, we detected down-regulation of the negative cell cycle regulator p21WAF1 in HCECpatH2O2C1-C3, which coincided with up-regulation of the positive cell cycle regulators CDK6 and cyclin D2 compared with the HCEC control (Fig. 5C). Moreover, increased β-catenin levels and increased expression of c-myc and c-fos were found (Fig. 5C), supporting further our hypothesized link to tumourigenesis. We were also able to detect overexpression of the death receptor TRAIL-R1/DR4 and, interestingly, observed down-regulation of caspases in HCECpatH2O2C1-C3 (Fig. 5C), which was paralleled by ATM down-regulation (Fig. 5A). However, the decreased ATM levels observed in recovery from oxidative stress (Fig. 5A, altered HCECpatH2O2C1-C3) seem to be the result of previous caspase-dependent ATM degradation during oxidative stress. We also detected down-regulation of proteins of the JNK pathway, such as p21WAF1. These results are consistent with the observed caspase-dependent suppression of the JNK pathway as second response to oxidative stress (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the JNK pathway, including caspases, represents a non-apoptotic pathway with the potential to link inflammation-associated ROS exposure and tumourigenesis. In this context, as reported by Heckman et al. for transformed rat tracheal epithelial cell lines 28, we also observed a more compact shape with decreased filopodia formation as morphological change in HCECpatH2O2C3 compared with the normal HCEC phenotype, which is characterized by a flattened shape with filopodial extensions (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 6.

Restoration of the normal HCEC phenotype through caspase inhibition. (A) Phase contrast micrographs showed that treatment of HCECpatH2O2C3 with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK led to the restoration of the morphological HCEC phenotype after 24 hrs. (B) FITC-Phalloidin-staining of HCECpatH2O2C3, HCECpatH2O2C3 treated with Z-VAD-FMK and HCEC. Filopodia are marked. (C) HCECpatH2O2C3 were treated with caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, and protein expression of γ-H2AX and p21WAF1 was analysed after 72 hrs. An increase in both γ-H2AX and p21WAF1 expression was detected. (D) Cell numbers of HCEC, HCECpatH2O2C3 and Z-VAD-FMK-treated HCECpatH2O2C3 after 72 hrs. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Determination of percental filopodia-containing cells of HCEC and HCECpatH2O2C3 and of Z-VAD-FMK-treated HCECpatH2O2C3 after 24 and 48 hrs. Data indicate mean ± SEM and were obtained from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (F) Immunohistochemical analysis of p-JNK in normal colonic mucosa, active ulcerative colitis (UC) and UC in complete remission.

Restoration of the HCEC phenotype by caspase inhibition

To prove whether caspase activity is linked to a pro-survival function, thus altering the normal HCEC phenotype including its DNA-damage sensitivity, proliferation capacity and morphology, we incubated HCECpatH2O2C3 with Z-VAD-FMK. Indeed, we could restore DNA-damage sensitivity of the cells by increasing γ-H2AX levels (Fig. 6C). In addition, we were able to increase p21WAF1 expression (Fig. 6C). In line with increased γ-H2AX and p21WAF1 expression following caspase inhibition, Z-VAD-FMK-treated HCECpatH2O2C3 also showed decreased proliferation 72 hrs following Z-VAD-FMK treatment (Fig. 6D, P = 0.051). Furthermore, we could reverse the morphological phenotype of altered HCEC (Fig. 6A and B). As HCEC are characterized by filopodia formation (Fig. 6A), we determined the percentage of cells with filopodia formation of HCEC, as well as that of Z-VAD-FMK-treated HCECpatH2O2C3 after 24 and 48 hrs (Fig. 6E). We detected a significant increase in filopodia formation of HCECpatH2O2C3 following caspase inhibition (16.9–36.4% after 24 hrs, P = 0.001; 25.6–38.9% after 48 hrs, P = 0.031). These data support the restoration of the normal HCEC phenotype including its DNA-damage sensitivity, proliferation capacity and morphology by caspase inhibition.

In summary, the results obtained in this study link the non-apoptotic function of caspases to undetected DNA-damage and increased proliferation in this cellular model of hydrogen peroxide-associated colitis. We could also detect overexpression of upstream activated JNK (p-JNK) in active UC by immunohistochemistry as opposed to low activity in both the healthy mucosa and the UC in complete remission (Fig. 6F). These results are in line with our cell culture studies where increased levels of p-JNK have been shown after inflammatory stress (Fig. 1B). This suggests that the results obtained in this cell culture-based study may also reflect events occurring in the in vivo situation.

Discussion

Oxidative stress activates DNA-damage checkpoints via JNK

Constant exposure of cells to DNA-damaging molecules such as ROS during the inflammatory process in IBD is likely to promote tumour development. The well-characterized DNA-damage response mechanisms provide cells with DNA-repair and cell cycle checkpoints. Dysfunction of genes involved in checkpoints and repair are hallmarks of tumourigenesis. A number of proteins are responsible for the control of cell cycle phase progression, including ATM, ATR, Chk1, Chk2 and p53 as the main signalling molecules. Recent evidence also suggests a role for MAPK's in cell cycle checkpoint control, and their dysregulation is potentially related to tumour development 8. MAPK's are known as ROS targets, and the resultant signals are generally coupled to transcriptional activity in the nucleus. However, the function of cell cycle arrest in UC is poorly understood, and it is not known whether arrest links reparative and uncontrolled proliferative response.

We found JNK-dependent cell cycle arrest in HCEC via induction of p21WAF1 following oxidative stress. In addition, we showed that γ-H2AX is a JNK-regulated protein, implying JNK also a role in DNA-repair. This suggests that JNK may play an important role in linking inflammation to tumourigenesis by linking reparative and uncontrolled proliferative response. Importantly, we also observed an activation of the JNK MAPK's in UC samples. This suggests that besides apoptosis, cell cycle arrest also plays an important role in UC. Recently, the involvement of JNK has been strongly implicated in acute inflammation 29. G2/M arrest has also been reported to be JNK-dependent following oxidative stress 30. Based on Araki's study, enhanced cell cycle promotion in DSS-induced colitis in mice and inflammation in UC patients could be a reaction that follows cell cycle arrest 7, but both these observations and the involvement of JNK in the process have to be proven experimentally in some detail.

In addition, colitis ulcerosa is associated with increased cytokine release. This could also be observed in our cellular model of H2O2-associated colitis for Il-13 and TGFβ, whereas levels of Il-6 and Il-8 remained unchanged. However, the release of Il-6 was found to be JNK-dependent, that of TGFβ was JNK- and caspase-dependent and that of Il-13 was only caspase-dependent. Il-8 and Il-13 were negatively regulated via JNK activity. In conclusion, we suggest that Il-13 and TGFβ may play a role in H2O2-associated colitis. In this context, Kawashima et al. recently reported a role of Il-13 in damage of intestinal mucosa 31. TGFβ increased in recovery from oxidative stress, and this fits with the observation that TGFβ depresses mucosal inflammation, promoting tissue repair 32.

Interestingly, H2O2 treatment caused a transient activation of proteins such as p-JNK p-c-jun, p21WAF1 and γ-H2AX with their induction at 24 hrs and their decline at 72 hrs, which is a characteristic sign of recovery. Moreover, JNK levels are decreased following H2O2 at all time-points. However, the p54 isoforms are diminished more strongly than the p46 isoforms compared with the controls. Caspases 3, 8 and 9 levels also underlay a transient nature with their induction at 24 hrs and their reduction at 72 hrs, which supports their down-regulation in HCEC cycles. However, cleaved caspases levels were still above control level at 72 hrs. This led us to suggest that caspases were activated in situ. Moreover, all H2O2-regulated proteins such as p-c-jun, p21WAF1, γ-H2AX and caspases 3, 8 and 9 were JNK-regulated at all time-points.

Interestingly, we found up-regulated TRAIL-R1/DR4 in H2O2-exposed HCEC and in altered HCEC. Members of the TNF1 receptor are critically involved in inflammatory, immune regulatory and pathophysiological reactions, including the induction of apoptosis 33. However, novel studies show the involvement of this receptor in non-apoptotic pathways such as NFκB- 34 and MAPK-pathway, in particular JNK 15.

Override of DNA-damage checkpoints links reparative and uncontrolled proliferative response

We found caspases 3, 8 and 9 as JNK-regulated proteins. Our cell cycle analysis of H2O2-treated HCEC following caspase inhibition showed (i) an increased cell population in the G1-phase as first response and (ii) an increased population of S-phase and then apoptotic HCEC (cell debris) as second response. These results are consistent with the observation that the level of γ-H2AX is increased following caspase inhibition. Thus, we presume that there is an important link between γ-H2AX and the activation of DNA-damage checkpoints that control both induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. This hypothesis is supported by Fragkos et al., who reported on the requirement of γ-H2AX for the activation of DNA-damage checkpoints 35. We further suggest that caspases mediate the progression of cells through the G1- and S-phase by suppression of H2AX phosphorylation, thereby overriding the G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint despite the presence of DNA-damage, and this seems to be the link to survival.

Caspases-dependent activation of JNK in acute phase and its suppression in chronic phase

We observed caspase-dependent activation of JNK following oxidative stress (24 hrs) and its suppression following recovery from oxidative stress (72 hrs). As caspases expression is induced via activated JNK, suppressed JNK activation should cause reduced levels of caspases. Indeed, in recovery from oxidative stress and in the model of chronic exposure, the caspases were reduced in comparison to the control. We found increased proliferation of HCECpatH2O2C1-C3 accompanied by down-regulation of p21WAF1 and up-regulation of oncogenic transcription factors such as c-myc and c-fos, as well as of β-catenin. The extent of their expression differed in the cycles. However, expression levels of the negative cell cycle regulator p21WAF1 were below that of HCEC control, and expression levels of proteins positively triggering proliferation were above that of HCEC control in each cycle, especially those of β-catenin and c-fos in the 3rd cycle. We therefore propose that the interplay of these factors may contribute to increased proliferation of the respective cycle with highest proliferation of the 3rd cycle.

In conclusion, caspases were found to circumvent DNA-damage checkpoints, leading to increased proliferation, decreased DNA-damage sensitivity and changed cell morphology of altered HCEC. However, caspases were down-regulated in HCEC cycles. We therefore presume that not the levels of caspases but rather their activities are crucial.

Caspases circumvent DNA-damage checkpoints by degradation of the DNA-damage checkpoint protein ATM

Caspases primarily have two functions: (i) the processing and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and (ii) the cleavage of multiple proteins during apoptosis 36. Among the caspases expressed in human cells, caspases 1, 4 and 5 are primarily involved in inflammatory responses by cytokine processing. Caspases 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 are implicated in apoptosis. Besides these major functions, experimental evidence suggests that caspases might play non-apoptotic roles in processes that are crucial for tumourigenesis such as cell proliferation, migration or invasion 11, 12. Caspases are also involved in the non-proteasomal degradation of inflammatory proteins. Ravi et al. reported the repression of NFκB activity in Jurkat T cells following CD95 binding by inducing the proteolytic cleavage of NFκB p65 (RelA) and p50 by caspase-3-related proteases 37. Furthermore, Matthews et al. documented a caspase-dependent proteolytic cleavage of STAT3α 38, which may play an important role in modulating STAT3 transcriptional activity. Therefore, it seems that caspases suppress inflammatory signalling by proteolytic degradation of inflammatory proteins such as NFκB and STAT3. This could be a potential link to tumourigenesis following carcinogen exposure.

Studies have highlighted the role of caspases in DNA-damage response. Recent publications suggest that caspase 2 may have a function in response to DNA-damage 39, 40. Indirect evidence that caspase 2 can regulate the cell cycle is based on an association identified between caspase 2 and cyclin D3 41. However, this might provide a link between the cell cycle and cell death.

We could show that oxidative stress led to caspase-mediated degradation of ATM that is upstream of γ-H2AX. The resultant undetected DNA-damage and increased proliferation in altered HCEC may serve to initiate tumourigenesis; both proliferation and DNA-damage are hallmarks of neoplastic change. In addition, we suggest that the increase in γ-H2AX protein levels following caspase inhibition is responsible for increased DNA-damage sensing and G1/S- and intra-S-checkpoint activation, and this led to increased G1- and S-cell population and increased apoptosis. The proteolytic inactivation of ATM by caspases has recently been reported by Wang et al. 42. However, ATM was proteolytically cleaved during cisplatin-induced tubular cell apoptosis.

Overall, loss of functional caspases is not a common event in human cancer, and evasion of apoptosis does not seem to represent a general hallmark of cancer. However, caspases may be involved in tumourigenesis by executing their non-apoptotic functions. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate that caspases might provide a link between cell cycle checkpoint control, cell survival and increased proliferation by proteolytic inactivation of the DNA-damage response protein ATM in HCEC following oxidative stress. Clearly, more work is required to elucidate the functional complexity of caspases in inflammation-associated cancer.

HCEC are an adequate model to study the link between colonic inflammation and neoplastic transformation

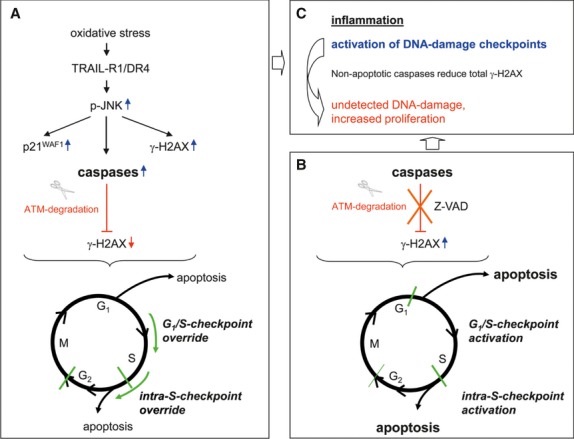

We have established a model of how oxidative stress mediates survival of HCEC (Fig. 7):

Fig. 7.

Proposed model of how the non-apoptotic function of caspases allows survival and proliferation of colonic epithelial cells in H2O2-associated colitis during oxidative stress. (A) H2O2 leads to the induction of the receptor TRAIL-R1/DR4, which, in turn, activates the JNK pathway including p21WAF1, γ-H2AX and caspases. This results in S and G2/M cell cycle arrest. However, caspases are involved in ATM degradation, and this leads to γ-H2AX down-regulation. Caspase activity circumvents G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint control by override and progression of cells through the G1- and S-phase (survival). (B) Inhibition of caspase activity cause γ-H2AX up-regulation and accumulation of cells in G1, S, as well as in debris (apoptosis). (C) Inflammation-associated ROS cause activation of DNA-damage checkpoints. However, caspase activity causes reduced total γ-H2AX, which leads to undetected accumulation of DNA-damage and increased proliferation of altered HCEC.

Oxidative stress leads to the induction of the TRAIL-Receptor 1/DR4, which, in turn, seems to activate JNK. Consequently, JNK induces the up-regulation of p21WAF1, γ-H2AX and caspases, resulting in S and G2/M cell cycle arrest. However, caspases are involved in ATM degradation, and this leads to γ-H2AX down-regulation.

Inhibition of caspase activity revealed an important link between γ-H2AX, G1/S- and intra-S-checkpoint activation. Firstly, we observed an increased G1-cell population following caspase inhibition, which seems to be the cause of γ-H2AX-mediated G1/S-checkpoint activation. Secondly, we detected increased S-cell population and subsequent apoptosis. This suggests γ-H2AX-mediated intra-S-checkpoint activation. Conversely, caspase activity circumvents G1/S- and intra-S checkpoint control by override and progression of cells through the G1- and S-phase (A). This led to increased proliferation of repeatedly H2O2-exposed HCEC (C).

We provide evidence for the importance of DNA-damage checkpoint activation linking reparative and uncontrolled proliferative response through reduced total γ-H2AX. This led to undetected accumulation of DNA-damage and increased proliferation of altered HCEC. Both accumulated DNA-damage and uncontrolled proliferation are hallmarks of neoplastic transformation. In addition, we found the JNK-caspase pathway to be responsible for γ-H2AX regulation. Importantly, caspase-dependent γ-H2AX down-regulation counteracts γ-H2AX up-regulation through p-JNK, which results in a reduction in the total γ-H2AX levels in altered HCECpatH2O2C3.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carola Kügler, Claudia Miethke and Stefanie Ritter for their excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Bernd Wüsthoff and Thomas Jonczyk-Weber for their important suggestions regarding manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 H2O2 causes induction of Il-13 and TGFβ, whereas the Il-6 and Il-8 release remained nearly unchanged. JNK inhibition using SP600125 led to decreased levels of Il-6 and TGFβ, but to increased levels of Il-8 and Il-13. Following inhibition of caspase activity (Z-VAD-FMK), release of IL-13 was abolished, and that of TGFβ was decreased.

Figure S2 (A) H2O2 results in the up-regulation and cleavage of pro-caspase 3. H2O2 induced caspase 3 expression after 24 hrs, whereas its expression was reversed after 48 and 72 hrs. (B) A solvent effect of DMSO on the decreased caspases expression following JNK inhibition could be excluded. Immunoblot analysis following JNK inhibition by the JNK inhibitor SP600125, compared with the combined DMSO and H2O2 control, revealed caspases 3, 8 and 9 as JNK-regulated proteins.

References

- 1.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Inflammation and oncogenesis: a vicious connection. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kundu JK, Surh YJ. Inflammation: gearing the journey to cancer. Mutat Res. 2008;659:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roessner A, Kuester D, Malfertheiner P, et al. Oxidative stress in ulcerative colitis-associated carcinogenesis. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:511–24. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terzic J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, et al. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2101–14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwamoto M, Koji T, Makiyama K, et al. Apoptosis of crypt epithelial cells in ulcerative colitis. J Pathol. 1996;180:152–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199610)180:2<152::AID-PATH649>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araki Y, Sugihara H, Hattori T. In vitro effects of dextran sulfate sodium on a Caco-2 cell line and plausible mechanisms for dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Oncol Rep. 2006;16:1357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poehlmann A, Roessner A. Importance of DNA damage checkpoints in the pathogenesis of human cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamkanfi M, Declerq W, Depuydt B. The caspase family. In: Los M, Walczak H, et al., editors. Caspases-Their Role in Cell Death and Cell Survival. New York: Kluwer Academic; 2003. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fadeel B, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. The most unkindest cut of all: on the multiple roles of mammalian caspases. Leukemia. 2000;14:1514–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamkanfi M, Declercq W, Vanden Berghe T, et al. Caspases leave the beaten track: caspase-mediated activation of NF-kappa B. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:165–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamkanfi M, Festjens N, Declercq W, et al. Caspases in cell survival, proliferation and differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:44–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang JY, Widmann C. Antiapoptotic signaling generated by caspase-induced cleavage of RasGAP. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5346–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5346-5358.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wajant H. Death receptors. Essays Biochem. 2003;39:53–71. doi: 10.1042/bse0390053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhlenbeck F, Haas E, Schwenzer R, et al. TRAIL/Apo2L activates c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) via caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33091–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.33091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blum S, Pfeiffer A, Tromvoukis Y. Immortalized adult human colon epithelial cell line. US Patent. 2001.

- 17.Bonnesen C, Eggleston IM, Hayes JD. Dietary indoles and isothiocyanates that are generated from cruciferous vegetables can both stimulate apoptosis and confer protection against DNA damage in human colon cell lines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6120–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai H, Al-Fayez M, Tunstall RG, et al. The rice bran constituent tricin potently inhibits cyclooxygenase enzymes and interferes with intestinal carcinogenesis in ApcMin mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1287–92. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crott JW, Liu Z, Keyes MK, et al. Moderate folate depletion modulates the expression of selected genes involved in cell cycle, intracellular signaling and folate uptake in human colonic epithelial cell lines. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duthie SJ, Narayanan S, Blum S, et al. Folate deficiency in vitro induces uracil misincorporation and DNA hypomethylation and inhibits DNA excision repair in immortalized normal human colon epithelial cells. Nutr Cancer. 2000;37:245–51. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC372_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plummer SM, Holloway KA, Manson MM, et al. Inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 2 expression in colon cells by the chemopreventive agent curcumin involves inhibition of NF-kappaB activation via the NIK/IKK signalling complex. Oncogene. 1999;18:6013–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbst U, Fuchs JI, Teubner W, et al. Malignant transformation of human colon epithelial cells by benzo[c]phenanthrene dihydrodiolepoxides as well as 2-hydroxyamino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;212:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathan CF, Root RK. Hydrogen peroxide release from mouse peritoneal macrophages: dependence on sequential activation and triggering. J Exp Med. 1977;146:1648–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.6.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poehlmann A, Habold C, Walluscheck D, et al. Cutting edge: Chk1 directs senescence and mitotic catastrophe in recovery from G(2) checkpoint arrest. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1528–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habold C, Poehlmann A, Bajbouj K, et al. Trichostatin A causes p53 to switch oxidative-damaged colorectal cancer cells from cell cycle arrest into apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:607–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fantini MC, Monteleone G, MacDonald TT. New players in the cytokine orchestra of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1419–23. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava N, Gochhait S, de Boer P, et al. Role of H2AX in DNA damage response and human cancers. Mutat Res. 2009;681:180–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckman CA, Varghese M, Cayer ML, et al. Origin of ruffles: linkage to other protrusions, filopodia and lamellae. Cell Signal. 2012;24:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy PK, Rashid F, Bragg J, et al. Role of the JNK signal transduction pathway in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;4:200–2. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seomun Y, Kim JT, Kim HS, et al. Induction of p21Cip1-mediated G2/M arrest in H2O2-treated lens epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 2005;11:764–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawashima R, Kawamura YI, Oshio T, et al. Interleukin-13 damages intestinal mucosa via TWEAK and Fn14 in mice-a pathway associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2119–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCartney-Francis NL, Wahl SM. Transforming growth factor beta: a matter of life and death. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:401–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muppidi JR, Tschopp J, Siegel RM. Life and death decisions: secondary complexes and lipid rafts in TNF receptor family signal transduction. Immunity. 2004;21:461–5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wajant H. TRAIL and NFkappaB signaling–a complex relationship. Vitam Horm. 2004;67:101–32. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(04)67007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fragkos M, Jurvansuu J, Beard P. H2AX is required for cell cycle arrest via the p53/p21 pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2828–40. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01830-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Festjens N, Cornelis S, Lamkanfi M, et al. Caspase-containing complexes in the regulation of cell death and inflammation. Biol Chem. 2006;387:1005–16. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravi R, Bedi A, Fuchs EJ, et al. CD95 (Fas)-induced caspase-mediated proteolysis of NF-kappaB. Cancer Res. 1998;58:882–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews JR, Watson SM, Tevendale MC, et al. Caspase-dependent proteolytic cleavage of STAT3alpha in ES cells, in mammary glands undergoing forced involution and in breast cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorstyn L, Puccini J, Wilson CH, et al. Caspase-2 deficiency promotes aberrant DNA-damage response and genetic instability. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1288–98. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar S. Caspase 2 in apoptosis, the DNA damage response and tumour suppression: enigma no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nrc2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendelsohn AR, Hamer JD, Wang ZB, et al. Cyclin D3 activates Caspase 2, connecting cell proliferation with cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6871–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072290599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Pabla N, Wang CY, et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of ATM during cisplatin-induced tubular cell apoptosis: inactivation of its kinase activity toward p53. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:1300–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00509.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.