Abstract

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) has been implicated in the development of heart disease. Nonetheless, the crosstalk between factors secreted from EAT and cardiomyocytes has not been studied. Here, we examined the effect of factors secreted from EAT on contractile function and insulin signalling in primary rat cardiomocytes. EAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) were isolated from guinea pigs fed a high-fat (HFD) or standard diet. HFD feeding for 6 months induced glucose intolerance, and decreased fractional shortening and ejection fraction (all P < 0.05). Conditioned media (CM) generated from EAT and SAT explants were subjected to cytokine profiling using antibody arrays, or incubated with cardiomyocytes to assess the effects on insulin action and contractile function. Eleven factors were differentially secreted by EAT when compared to SAT. Furthermore, secretion of 30 factors by EAT was affected by HFD feeding. Most prominently, activin A-immunoreactivity was 6.4-fold higher in CM from HFD versus standard diet-fed animals and, 2-fold higher in EAT versus SAT. In cardiomyocytes, CM from EAT of HFD-fed animals increased SMAD2-phosphorylation, a marker for activin A-signalling, decreased sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a expression, and reduced insulin-mediated phosphorylation of Akt-Ser473 versus CM from SAT and standard diet-fed animals. Finally, CM from EAT of HFD-fed animals as compared to CM from the other groups markedly reduced sarcomere shortening and cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes in cardiomyocytes. These data provide evidence for an interaction between factors secreted from EAT and cardiomyocyte function.

Keywords: epicardial adipose tissue, adipokines, cardiomyocytes, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a common characteristic of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the metabolic syndrome [1]. Risk factors for the metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, increased visceral adipose tissue mass, obesity, increased plasma glucose and insulin resistance, also associate with expansion of the epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) [2–5]. EAT is a visceral thoracic fat depot, located at the aortic arch, along the large coronary arteries and on the surface of the ventricles and the apex of the human heart [6]. Because EAT is not separated by a fascia from the myocardium, factors secreted from EAT can directly affect the myocardium and coronary vessels [2, 6, 7].

EAT is a source of various adipokines, including adiponectin, fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4), interleukin (IL) 1, IL6, monocyte chemoattractive protein-1, leptin, resistin and tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [5, 8–14]. Patients with obesity, T2D and coronary artery disease (CAD) show elevated plasma levels and altered expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines in EAT [7, 15]. Conversely, expression and circulating levels of protective factors, like adiponectin, is lower in patients with CAD [9, 16]. Furthermore, FABP4 suppresses contractile function in vitro in isolated rat cardiomyocytes [17]. Although these data indicate that secretory products from EAT may contribute to the pathogenesis of CVD, studies about diabetes-related alterations in adipokine secretion by EAT are limited.

Here, we studied the interaction between secretory products from EAT and cardiomyocyte function and insulin signalling. Therefore, EAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) were isolated from guinea pigs, which were fed a high-fat diet (HFD) to induce glucose intolerance and contractile dysfunction [18, 19]. In contrast to laboratory rats and mice, guinea pigs contain abundant amounts of EAT, which increases with age [6, 20]. Conditioned media (CM) generated from adipose tissue explants were profiled for adipokine secretion using antibody arrays. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes were used to assess the effects of CM in vitro on insulin signalling, contractile function and cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes. Our data provide evidence for a detrimental effect of factors secreted from the EAT on myocardial function, and suggest a role for EAT in the pathogenesis of heart disease.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ‘Principle of laboratory animal care’ (NIH publication No. 85–23, revised 1996) and the current version of the German Law on the protection of animals. Seven-week-old female guinea pigs (Crl:HA, Dunkin Hartley) were purchased from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany), and housed under standard conditions at a temperature of 18–20°C and a day–night rhythm of 12 hrs, and fed either a HFD or standard diet (SD). The SD was obtained from Ssniff (Soest, Germany), while the HFD diet was obtained from Altromin (Lage, Germany). The composition of the diets is listed in Table S1.

Echocardiography

In vivo cardiac function was measured using non-invasive transthoracic echocardiography with a 6- to 15-MHz transducer (SONOS 5500; Hewlett Packard, Geneva, Switzerland) in guinea pigs anaesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen-enriched air (95% O2) at 28 weeks after initiation of the diet. All echocardiographic images were recorded by the same investigator who was blinded for the animal group. Two-dimensional guided M-mode images in the parasternal short axis of the left ventricle (LV) were obtained just below the level of the midpapillary muscles. At end systole and end diastole, LV lumen diameter, LV ventricular diameter and posterior wall and interventricular septum wall thicknesses were determined for five cardiac cycles and averaged. The LV dimensions were used to calculate the left ventricular mass and the cardiac systolic parameters fractional shortening and ejection fraction as described [19].

Glucose tolerance test

A glucose tolerance test was performed after 29 weeks on the diet. Guinea pigs were food-deprived for 20 hrs, and blood glucose levels were determined before (0 min.) and after (15, 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 min.) intraperitoneal injection of 2 g glucose/kg body weight in blood taken from the ear vein.

Preparation and characterization of conditioned media

Thirty weeks after initiation of the diets, guinea pigs were killed by CO2 inhalation, after which EAT and SAT were collected and used to generate CM as described [21, 22]. Briefly, on day 1 adipose tissue were washed three times with PBS, supplemented with antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C and cut with scissors into 10 mg small fat explant pieces. Subsequently, adipose tissue explants were washed three times with PBS and centrifuged 1 min. at 1200 rpm at room temperature. Then, fat explants were cultured in adipocyte media (AM) [DMEM F12 containing 10% foetal calf serum, 33 μmol/l biotin, 17 μmol/l panthothenate (all from Invitrogen) and antibiotic-antimycotic] overnight in a humidified atmosphere (95% air and 5% CO2) at 37°C. To generate CM, 100 mg of fat tissue explants were cultured in 1 ml AM without serum for 24 hrs. Then, CM were collected and stored as aliquots at –80°C until further use.

Antibody arrays (RayBio human cytokine antibody G series 2000; Ray Biotech, Inc., Norcross GA, USA) were used to determine the secretory profile of the CM exactly according to the supplier’s instructions.

Effects of conditioned media on primary adult rat cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from male Lewis rats (Lew/Crl) as described [23], and cultured for 24 hrs on laminin-coated dishes before exposure to CM. The effects of CM on protein expression and phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes were determined by Western blotting. The effects of CM on sarcomere shortening and cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes were determined following electric stimulation of the cells with 1 Hz on a contractility and fluorescence system from IonOptix (Dublin, Ireland) using Indo-1 (Invitrogen) as Ca2+ indicator.

Isolation and culture of adult primary rat cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes were prepared from male Lewis rats (LEW/Crl, Charles River) weighing 250–350 g using a Langendorff perfusion system as described [23]. Briefly, rats were killed following anaesthesia with ketamine (100 mg/kg; Ratiopharm, Ulm, Germany) and xylazine (Rompun, 5 mg/kg) (Bayer Healthcare, Leverkusen, Germany). The anaesthetic further contained heparin (666 μl/kg) (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany). Isolated hearts were retrograde perfused through the aorta for 5 min. with Ca2+-free Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate buffer (KRBB) [composition: NaCl, 35 mM; KCl, 4.75 mM; KH2PO4, 1.19 mM; Na2HPO4, 16 mM; NaHCO3; 25 mM; sucrose, 134 mM; 4-2-hydroxyethyl-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 10 mM; glucose, 10 mM] gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After the addition of 0.1 mmol/l CaCl2, the isolated heart was perfused for 5 min. with KRBB [23], followed by KRBB, containing 1.25 g/l bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 0.7 g/l collagenase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) and 0.1 g/l hyaluronidase (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany). Perfusion medium was gassed with O2. After 20 min., the softened heart was minced and incubated for 5 min. at 37°C. Then, the dispersion was filtered through a nylon mesh, and centrifuged for 5 min. at 500 rpm. After centrifugation, cell pellet was washed with HEPES buffer (composition: NaCl, 130 mM; KCl, 4.7; KH2PO4, 1.2 mM; HEPES, 25 mM; glucose, 5 mM, equilibrated with O2), containing 3 g/l bovine serum albumin (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). Subsequently, cells were incubated for 7 min. at 37°C in HEPES buffer containing 0.059 units/ml trypsin and treated as described [23]. Isolated cells were seeded on laminin-coated dishes (1 × 105 cells per 35 mm plate) in Medium 199 with Hank’s salts, supplemented with insulin, transferrin, selenium, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 10% foetal calf serum (all from PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria) on laminin-coated 35 mm culture dishes (for signalling experiments: Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Solingen, Germany; for fluorescence analysis: ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany). The medium was renewed after four hrs, and culture was continued overnight.

Western blot analysis

Ventricular biopsies collected from SD- or HFD-fed guinea pigs were homogenized in Triton X-100 lysis buffer, containing 50 mM Tris.HCl [pH 7.5]; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% Triton X-100; 1 mM NaF; 1 mM Na3VO4; 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT); and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Following 2 hrs incubation at 4°C under gentle rotation, homogenates were cleared by centrifugation for 15 min. at 12,000 rpm and 4°C. Cultured cardiomyocytes were incubated for 24 hrs with CM (diluted 1:4 with AM) or AM. Then, cells were stimulated for 10 min. with insulin (100 nM), washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed for 2 hrs at 4°C in Triton X-100 lysis buffer under gentle rotation. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (15 min.; 12,000 rpm; 4°C), and protein content was determined using Bradford reagent (Biorad Laboratories, München, Germany). Ten micrograms of protein was loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blotting, membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline, containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat dry milk for 2 hrs at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. After washing, membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary HRP-conjugated antibody for 2 hrs at room temperature and washed again. All antibodies and dilutions are listed in Table S2. Bound antibodies were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence and quantified by using a LUMI Imager system (Roche Diagnostics).

Measurement of sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ transients

For analysis of the effects of CM, cells were preloaded with Indo-1 (Invitrogen) for 15 min. at 37°C, washed once with AM and then incubated for 30 min. with CM or AM. For reversibility experiments, CM were removed and cells were incubated with AM for two hrs. Subsequently, contractile function and Ca2+ transients were analysed in cells showing an intact rod-shaped morphology and sarcomere length >1.6 μm. Before measurement was started, cells were electrically pre-stimulated for 5–10 min. with 1 Hz to reach a steady-state level for sarcomere shortening and Indo-1 fluorescence. Then, cells were paced with bipolar pulses of 5 ms duration at 1 Hz. The cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was monitored as a ratio of the fluorescence emission peaks at 475 and 400 nm. In each experimental condition, data files were recorded of 10 consecutive beats for at least 8 different cells. Sarcomere shortening and Ca2 transients were calculated using IonWizard (IonOptix).

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences between experimental conditions were evaluated by one-way anova or unpaired Student’s t-test using Graphpad Prism software (version 5). A value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

HFD feeding induces cardiac contractile dysfunction in guinea pigs

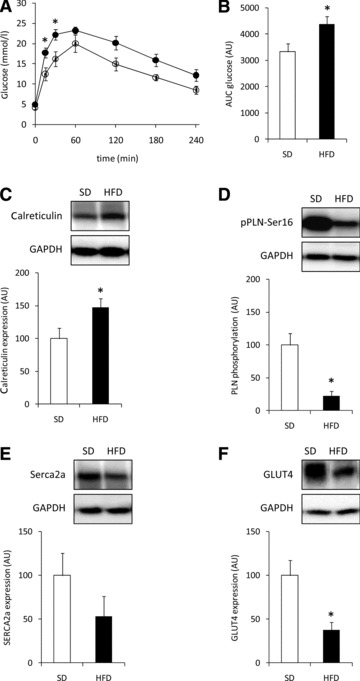

In comparison to SD-fed animals, feeding guinea pigs a HFD for 29 weeks induced mild glucose intolerance as determined by a glucose tolerance test (Fig. 1A and B). Table 1 shows the physiological and cardiac parameters after 28 weeks on the diets. There were no significant differences in body weight, EAT mass, left ventricular mass and the diastolic parameters. In the end systolic phase, the lumen diameter of the LV was increased in HFD-fed guinea pigs (P < 0.05). Accordingly, end systolic volume was increased (P < 0.05), and fractional shortening and the ejection fraction were decreased in HFD-fed animals (both P < 0.02) (Table 1). At the molecular level, protein expression of calreticulin (Fig. 1C) was higher and phosphorylation of phospholamban (Fig. 1D) was lower in hearts from HFD- versus SD-fed animals. Furthermore, expression of sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA)2a tended to be decreased in hearts from HFD versus SD-fed animals (Fig. 1E). Finally, protein expression of the insulin-regulated glucose transporter GLUT4 was substantially lower in HFD hearts (Fig. 1F). Collectively, these data indicate contractile dysfunction in hearts from HFD-fed animals.

Fig 1.

Animal characteristics. (A) Blood glucose levels and (B) area under the curve of blood glucose levels after a glucose tolerance test in guinea pigs fed a SD (open circles; open bars; n= 5) or HFD (closed circles; filled bars; n= 10) for 29 weeks. (C–F) Representative immunoblots and quantification of calreticulin expression (C), phosphorylation of PLN (D), expression of SERCA2a (E) and Glut4 (F) in ventricular tissue from guinea pigs fed a SD (open bars) or HFD (black bars) for 30 weeks. Equal loading was verified by probing the immunoblots with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody. All data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M.

Table 1.

In vivo cardiac characteristics of guinea pigs after 28 weeks on a SD or HFD

| Standard diet (n= 4) | HFD (n= 5) | |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological parameters | ||

| Body weight (g) | 945 ± 20 | 929 ± 44 |

| LV mass (g) | 3.27 ± 0.20 | 2.94 ± 0.24 |

| EAT mass (g) | 1.61 ± 0.08 | 1.60 ± 0.09 |

| LV diastolic parameters | ||

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) | 4.73 ± 0.36 | 3.94 ± 0.28 |

| Lumen diameter (mm) | 8.23 ± 0.31 | 8.78 ± 0.32 |

| Interventricular septum wall thickness (mm) | 2.48 ± 0.08 | 2.42 ± 0.18 |

| Ventricular diameter (mm) | 15.43 ± 0.26 | 15.14 ± 0.34 |

| End diastolic volume (μl) | 563 ± 58 | 688 ± 77 |

| LV systolic parameters | ||

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) | 5.58 ± 0.41 | 5.50 ± 0.78 |

| Lumen diameter (mm) | 3.98 ± 0.38 | 5.08 ± 0.24* |

| Interventricular septum wall thickness (mm) | 4.15 ± 0.24 | 3.64 ± 0.15 |

| Ventricular diameter (mm) | 13.70 ± 0.22 | 14.22 ± 0.77 |

| End systolic volume (μl) | 67.72 ± 16.91 | 134.7 ± 19.8* |

| Fractional shortening (%) | 51.95 ± 3.12 | 42.21 ± 0.88* |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 88.48 ± 2.17 | 80.65 ± 0.88* |

P < 0.05 versus SD.

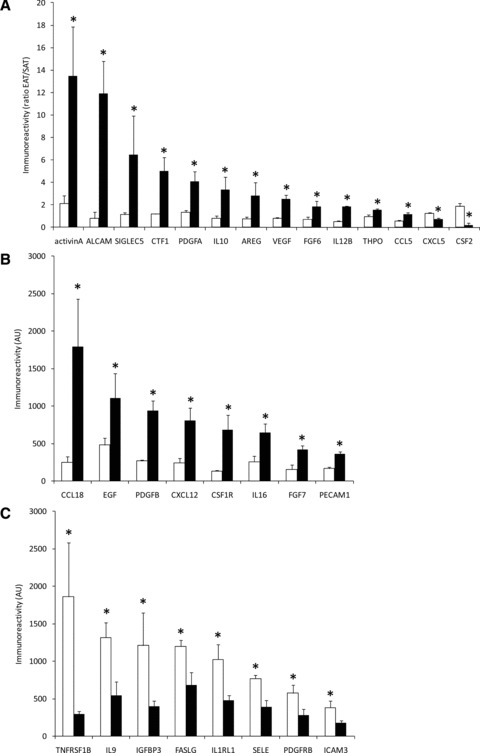

Characterization of conditioned medium from epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue

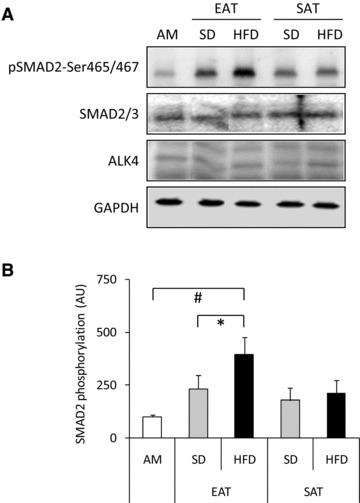

To study the interaction between EAT and the myocardium, CM were generated from EAT, and characterized using antibody arrays. The factors secreted by EAT were compared with CM generated from SAT of the same SD-fed animals. Table S3 shows the relative immunoreactivity obtained for the 174 factors present on the arrays for CM-EAT and CM-SAT. Eleven factors were differentially secreted by EAT when compared to SAT. Specifically, adiponectin (ADIPOQ) immunoreactivity was decreased in EAT versus SAT, while immunoreactivity for cardiotrophin (CTF1), activin A, endoglin, E-selectin (SELE), IL2Rγ, IL5Rα, platelet-derived growth factor A (PDGFA), PDGF receptor A (PDGFRA), Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (PECAM1), Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 [VEGFR2, also known as Kinase insert Domain containing Receptor (KDR)] was increased in EAT versus SAT (all P < 0.05). The immunoreactivity of 30 factors in EAT was affected by HFD feeding (Fig. 2). Specifically, 12 factors, i.e. activin A, ALCAM, SIGLEC5, CTF1, PDGFA, IL10, amphiregulin (AREG), VEGF, fibroblast growth factor 6 (FGF6), IL12B, thrombopoietin (THPO) and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5), were selectively increased by HFD feeding in EAT versus SAT (Fig. 2A). Immunoreactivity of chemokine CXC ligand 5 (CXCL5), and colony stimulating factor 2 (CSF2) was selectively decreased by HFD feeding in EAT versus SAT (Fig. 2A). Sixteen factors were affected by HFD feeding in CM from both EAT and SAT. Figure 2B shows an increased immunoreactivity for CCL18, EGF, PDGFB, CXCL12, CSF1R, IL16, FGF7 and PECAM1 in CM-EAT from HFD versus SD-fed animals (all P < 0.05). Figure 2C shows a decreased immunoreactivity for TNFRSF1B, IL9, IGFBP3, FASLG, IL1R1, SELE, PDGFRB and ICAM3 in CM-EAT from HFD versus SD-fed animals (all P < 0.05). These data show that HFD feeding differentially affects the secretion of multiple factors by EAT and SAT, with most notable changes observed for activin A. Activin A, a homodimer of two activin βA– subunits encoded by the inhibin A (INHBA)-gene, is a member of the transforming growth factor (TGF-β) superfamily, which utilizes the SMAD2/3-signalling pathway [24]. Therefore, we examined whether CM affected SMAD2-phosphorylation levels in rat cardiomyocytes. Incubation of cardiomyocytes with CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals increased SMAD2-phosphorylation by 4-fold (P < 0.05) when compared to control AM and 1.7-fold when compared to CM-EAT from SD-fed animals (Fig. 3). Exposure of cardiomyocytes to CM-SAT had no significant effect on SMAD2-phosphorylation (Fig. 3). CM had no effect on the expression of the activin receptor type 1B (also known as Alk4) and SMAD2/3 (Fig. 3A). Thus, the enhanced activin A-immunoreactivity in CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals is paralleled by the ability to induce SMAD2-phosphorylation in rat cardiomyocytes.

Fig 2.

Characterization of secretory products of EAT and SAT. CM generated from EAT and SAT from SD- and HFD-fed guinea pigs were profiled using antibody arrays. (A) Ratio of immunoreactivity for secretory products from EAT over SAT that are selectively altered in EAT by the HFD compared to SD. White bars: SD-CM; black bars: HFD-CM. Immunoreactivity of secretory products in EAT that are up-regulated (B) or down-regulated (C) by the HFD in CM from EAT. All data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n= 4 per group). Differences between the experimental groups were calculated by one-way anova and unpaired Student’s t-tests. *P < 0.05 HFD versus SD.

Fig 3.

Effect of conditioned medium from EAT and SAT on SMAD2-phosphorylation. Lysates prepared from rat cardiomyocytes incubated with control AM or CM (diluted 1:4) from EAT and SAT from SD- and HFD-fed guinea pigs for 24 hrs were analysed by Western blotting with antibodies recognizing phosphorylated SMAD2-Ser465/467, total SMAD2/3 and activin A receptor type 1B (Alk4). Equal loading was verified by probing the immunoblots with GAPDH antibody. Representative immunoblots (A) together with quantification (B) are shown. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n= 5 per group). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; black bars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Differences between the experimental groups were calculated by one-way anova and unpaired Student’s t-tests. #P < 0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05 HFD versus SD.

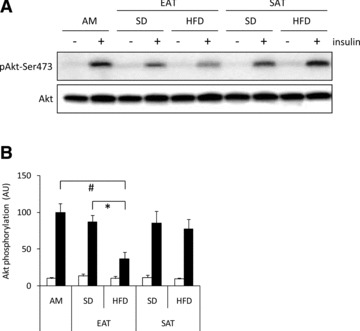

Effect of conditioned media from epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue on insulin action

Short-term exposure (3 hrs) of cardiomyocytes to CM had no effect on insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation (data are not shown). However, when cardiomyocytes were exposed for 24 hrs to CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals, the induction of insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation was reduced by ∼60% as compared to CM-EAT from SD-fed animals or AM (Fig. 4A/B) (both P < 0.05). CM-SAT from either SD- or HFD-fed had no inhibitory effect on insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4A/B). Protein expression levels of Akt (Fig. 4A) were not affected by exposure to CM.

Fig 4.

Effect of conditioned medium from EAT and SAT on insulin action. Lysates prepared from rat cardiomyocytes incubated with control AM or CM (diluted 1:4) from EAT and SAT from SD- and HFD-fed guinea pigs for 24 hrs were analysed by Western blotting with antibodies recognizing total and Ser473-phosphorylated Akt. Representative immunoblots (A) and quantification (B) of insulin-induced Akt-Ser473 phosphorylation. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n= 4 per group). Open bars: basal; filled bars: insulin stimulated cells (10 min.; 100 nM). Differences between the experimental groups were calculated by one-way anova and unpaired Student’s t-tests. #P < 0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05 HFD versus SD.

Effect of conditioned media from epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue on cardiomyocyte contractile function

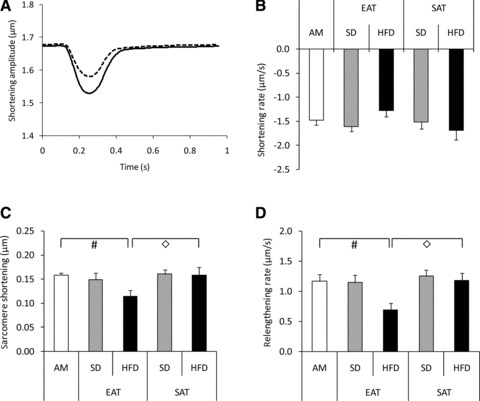

Time-dependent alterations in sarcomere length were recorded in primary rat cardiomyocytes incubated with AM or CM from the various groups (Fig. 5A). Exposure to CM did not affect cell morphology and resting sarcomere length. Following electric stimulation of the cells with 1 Hz, peak sarcomere shortening and return velocity (Fig. 5C/D) were reduced following a 30 min. exposure to CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals. Departure velocity was not affected by CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals (Fig. 5B). CM from the other experimental groups had no significant effect on sarcomere length when compared to AM (Fig. 5B–D). When the concentration of CM were increased by 2-fold, a further reduction of peak sarcomere shortening and return velocity was found following exposure of cardiomyocytes to CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals (Fig. S1; both P < 0.05). Also departure velocity was significantly lower in cells incubated with a higher concentration of CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals as compared to AM and CM-SAT from HFD-fed animals (both P < 0.05; (Fig. S1). Finally, the effects elicited by more concentrated CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals on determinants of sarcomere length were significantly lower when compared to CM-EAT from SD-fed animals (Fig. S1).

Fig 5.

Effect of conditioned medium from EAT and SAT on sarcomere shortening in cardiomyocytes. Rat cardiomyocytes were incubated with control AM or CM (diluted 1:4) from EAT and SAT from SD- and HFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. before analysis of contractile function. (A) Representative chart recording of alterations in sarcomere length in time. Black line: AM; dashed line: CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals. Effect of exposure of cardiomyocytes to CM on departure velocity of contraction (B), peak sarcomere shortening (C) and return velocity of contraction (D). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; black bars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of at least eight independent experiments. Differences between the experimental groups were calculated by one-way anova and unpaired Student’s t-tests. #P < 0.05 versus AM; ◊P < 0.05 EAT versus SAT.

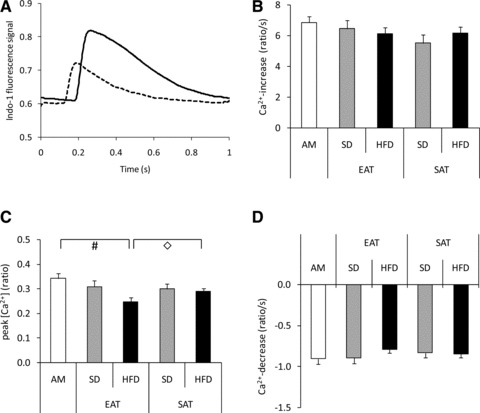

Time-dependent alterations in cytosolic [Ca2+] are presented in Figure 6A. A 30 min. exposure to CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals lowered peak [Ca2+] as compared to cells exposed to AM and CM-SAT from HFD-fed animals (both P < 0.05), without affecting departure- and return velocities (Fig. 6). However, when the concentration of CM-EAT was doubled, departure- and return velocity for alterations in cytosolic [Ca2+] were reduced in cells exposed to CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals versus AM and CM-EAT from SD-fed animals (Fig. S2).

Fig 6.

Effect of conditioned medium from EAT and SAT on cytosolic [Ca2+] in cardiomyocytes. Rat cardiomyocytes were incubated with control AM or CM (diluted 1:4) from EAT and SAT from SD- and HFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. before analysis of cytosolic [Ca2+]. (A) Representative chart recording of alterations in indo-1 fluorescence in time. Black line: AM; dashed line: CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals. Effect of exposure of cardiomyocytes to CM on [Ca2+] increase (B), peak [Ca2+] (defined as the ratio between Ca2+-bound Indo 1 and unbound free Indo 1) (C) and [Ca2+] decrease (D). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; black bars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of at least eight independent experiments. Differences between the experimental groups were calculated by one-way anova and unpaired Student’s t-tests. #P < 0.05 versus AM; ◊P < 0.05 EAT versus SAT.

Long-term incubation for 24 hrs of the cells with CM showed no further impairment of sarcomere shortening and cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes when compared to short-term incubation for 30 min. (data not shown). Analysis of the contractile parameters 2 hrs after replacement of the CM by AM showed that peak sarcomere shortening and peak [Ca2+] were still reduced in cardiomyocytes that were exposed to CM from EAT of HFD-fed animals in the lowest dilution tested (Fig. S3). In all other experimental conditions, contractile function was restored.

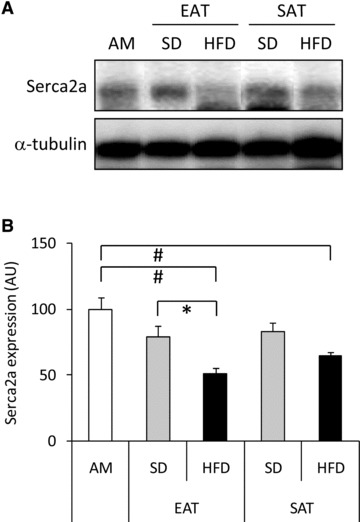

Effect of conditioned media from epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue on SERCA2a expression

Expression of SERCA2a, a key regulator of cardiac Ca2+ metabolism, was reduced in cardiomyocytes incubated with CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals when compared to AM and CM-EAT from SD-fed animals. CM-SAT from HFD-fed animals also slightly lowered SERCA2a expression whereas CM from the other groups had no effect (Fig. 7). Thus, the detrimental effects of CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals on contractile function are paralleled by a reduction in SERCA2a expression.

Fig 7.

Effect of CM from EAT and SAT on SERCA2a expression. Lysates prepared from rat cardiomyocytes incubated with control AM or CM (diluted 1:4) from EAT and SAT from SD- and HFD-fed guinea pigs for 24 hrs were analysed by Western blotting for SERCA2a- and α-tubulin expression. Representative Western blots (A) and quantitative analysis (B) are also shown. Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; black bars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n= 3 per group). Differences between the experimental groups were calculated by one-way anova and unpaired Student’s t-tests. #P < 0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05 HFD versus SD.

Discussion

The present study shows that the secretory profile of EAT is distinct from that of SAT. Furthermore, HFD-induced alterations in the factors secreted by EAT cause dysfunction of primary rat cardiomyocytes as illustrated by impairments in insulin signalling, sarcomere shortening, cytosolic Ca2+ metabolism and SERCA2a expression. Collectively, these findings show that diet-induced changes in EAT could contribute to the development of cardiomyocyte dysfunction.

Accumulating evidence from epidemiological studies has identified associations between EAT and clinical markers of the metabolic syndrome, T2D, CAD and cardiac function [3]. A recent report shows that obesity and CAD also affect the secretory profile of EAT in human beings [15]. Specifically, CM from EAT of these patients was found to induce atherogenic changes in monocyte migration and endothelial cell adhesion [15]. Yet, studies on qualitative alterations of EAT in relation to disease are often hampered by the lack of appropriate human controls, and the scarce amounts of EAT in frequently used laboratory rodents, like rat and mice [4, 6]. Therefore, in the current study, guinea pigs were used, in which EAT expands with age [20, 25]. HFD-fed guinea pigs showed glucose intolerance, indicative of reduced insulin sensitivity, in the absence of obesity, as previously also reported in HFD-fed rats [18, 19]. Although the HFD contained more calories than the SD, the HFD group consumed less of the diet as compared to the SD group, resulting in similar caloric intake, but with different food ingredients. For example, the concentration of saturated fatty acids was much higher in HFD than in SD. In addition, HFD-fed guinea pigs showed abnormalities in left ventricular function, like reductions in ejection fraction and fractional shortening similar to HFD-fed rats [19]. The observed alterations in GLUT4-, SERCA2a- and calreticulin expression, and phospholamban phosphorylation provide further support for a reduced cardiac function on HFD-fed guinea pigs.

A key finding in the present study is that secretory products from EAT from HFD-fed animals exert a cardiodepressant and negative inotropic effect on primary adult rat cardiomyocytes. This detrimental effect was dose dependent, and occurred within minutes after the addition of CM to the cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, the effect could be reversed by replacing CM by control medium. In support of a previous study, which demonstrated that primary human subcutaneous adipocytes secrete a cardiodepressant factor [26], we observed that cardiomyocyte dysfunction, could also be induced by a higher dose of CM-SAT from HFD-fed animals although to a significantly lower extent when compared to the same dose of CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals. In contrast to SAT, EAT is not separated by facial boundaries from the myocardium, and factors secreted from the EAT could directly affect the function of the underlying myocardium. The functional significance of the cardiodepressant activity secreted by SAT remains to be elucidated since it may only affect cardiomyocyte function via the systemic circulation. The negative effects of CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals on cytosolic Ca2+ transients in rat cardiomyocytes were accompanied by a reduction of protein expression of SERCA2a, a key regulator of cytosolic [Ca2+] in the heart [27]. Decreases in myocardial SERCA2a expression are a common characteristic of cardiopathological states in human beings [27], but have also been reported in animal models for diabetes-related heart disease [28]. Collectively, these findings indicate that secretory products from EAT regulate myocardial function, and that HFD-induced alterations in the EAT secretory profile could contribute to the diet-induced alterations in in vivo cardiac function in HFD-fed guinea pigs.

In patients with T2D, alterations in cardiac structure and function which are found even in the absence of hypertension and CAD are ascribed to diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetic cardiomyopathy often co-exists with myocardial insulin resistance [29, 30]. Here, we show for the first time that exposure of cardiomyocytes to secretory products from EAT of HFD-fed animals abrogates insulin-mediated phosphorylation of Akt, a key regulator of myocardial glucose uptake [30, 31]. In contrast to the effects on contractile function, the detrimental effects on insulin action were only observed upon prolonged incubation of the cardiomyocytes with CM, indicating that this detrimental effect is caused by a different mechanism. Abrogation of insulin-mediated Akt phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes was also described when cells were exposed to CM from epididymal adipose tissue from diabetic rats as compared to control rats [32]. In this study, the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation was paralleled by a reduced ability of insulin to stimulate glucose uptake. In obese Zucker diabetic rats, a decrease in insulin-mediated Akt phosphorylation could be linked to a decrease in insulin-mediated myocardial glucose utilization in vivo as determined by positron emission tomography under hyperinsulinaemic euglycaemic clamp conditions [33]. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence that secretory products of EAT from HFD-fed animals contribute to the induction of insulin resistance at the level of the Akt-pathway regulating myocardial glucose uptake.

In order to identify potential factors responsible for the detrimental effects caused by CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals, CM from the various experimental groups was further characterized. Glycerol and free fatty acids levels was similar in the CM of the experimental groups (data not shown). Also lactate content, before and after incubation with cardiomyocytes, did not differ between CM-EAT and CM-SAT, and was not affected by the dietary intervention (data are not shown). Therefore, it seems unlikely that an increased utilization of lactate as myocardial energy substrate, which negatively affects myocardial performance [34], contributes to the observed effects caused by CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals. In support of previous studies, which have ascribed cardiosuppressive effects to adipokines [17, 35–38], like FABP4, IL1β, IL6 and TNF-α, boiling was found to destroy the detrimental effect of CM on cardiomyocyte function. Therefore, the CM were evaluated for diet-induced alterations in adipokine secretion by EAT and SAT. With the use of antibody arrays, we found that the secretory profile of EAT differs from that of SAT, and that the secretory profiles in both depots were affected by HFD feeding. Although we could identify these differences, this approach has limitations. First, not all factors secreted by adipose tissue are present on the array, like FABP4. In addition, there are no specific arrays available for guinea pigs. Instead, we used human antibody arrays, and cannot exclude problems related to cross-reactivity between factors from guinea pigs and human beings. Similarly, some adipokines identified in the antibody array may not act on rat cardiomyocytes because of species differences. In this respect, we have attempted to examine the effects of CM on primary guinea pig cardiomyocytes. However, in our hands, the viability of the isolated cells was too low to allow the experiments described in this study.

Despite the limitations of our approach, in CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals, a selective increase in immunoreactivity for 12 factors, and loss of immunoreactivity for two factors was found. The most notable change in CM-EAT was observed for activin A. Immunoreactivity for activin A was 6.4-fold higher in CM from HFD-fed versus SD-fed animals and 2-fold higher in CM-EAT versus CM-SAT. Although the sequence for guinea pig activin A is still unknown, the activin A protein sequence is highly conserved (95.8% identical) among human beings, rats and mice. Furthermore, the alterations in activin A immunoreactivity were accompanied by biological activity of the CM, as illustrated by the induction of SMAD2-phosphorylation by CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals only. Although other factors present on the arrays like TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, HGF and IGFBP3, are also capable to regulate SMAD2-phosphorylation, immunoreactivity of these factors did not differ among the experimental groups. Multiple studies have linked activin A to cardiac dysfunction. Serum levels of activin A are elevated in patients with heart failure [39]. Furthermore, activin A increases the expression of genes involved in myocardial remodelling, like atrial natriuretic peptide, brain natriuretic peptide, matrix metalloproteinase-9, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, TGF-β1 and monocyte chemoattractive protein-1 [39], and inhibits the organization of sarcomeric proteins induced by leukaemia inhibitory factor in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes [40]. In line with this, recombinant activin A exerts a cardiodepressant activity on rat adult cardiomyocytes (S.G., D.M.O. and J.E., submitted for publication). Finally, in neonatal cardiomyocytes activin A has been found to induce the expression of suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) [40], a key repressor of insulin action [41]. Importantly, in the present study SOCS3 expression was elevated in hearts from HFD-fed guinea pigs (data not shown).

Beside activin A, also the immunoreactivity of other factors was selectively affected in CM-EAT from HFD-fed animals. Although alterations in serum levels have been reported in patients with cardiac dysfunction for some factors, like IL10 and CXCL5 [42–44], the role of most factors in relation to myocardial function and insulin sensitivity remains to be elucidated.

Another question that remains to be addressed is what underlies the diet-induced changes in the secretory profile from EAT. In the present study, CM were generated from adipose tissue explants. In addition to adipocytes, adipose tissue also contains other cell types, like pre-adipocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and lymphocytes, which can release a variety of chemo- and cytokines [45, 46]. Hypertrophy of adipose tissue in obesity and T2D is closely linked to low-grade inflammation [47]. This can be ascribed to accumulation of immune cells into the adipose tissue, and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [45, 46]. We could not obtain histological evidence for immune cell infiltration in EAT from HFD-fed guinea pigs, because of the unavailability of antibodies cross-reacting with guinea pig macrophage markers. However, a study performed on human beings with CAD reports the infiltration of immune cells in EAT [11]. Furthermore, a recent study shows that activin A expression is elevated in adipose tissue from obese individuals, and dramatically increased by factors secreted by macrophages isolated from obese adipose tissue [48]. Based on these findings, it seems likely that the observed alterations in the secretory profile of EAT from HFD-fed guinea pigs can be ascribed to infiltration of immune cells.

In conclusion, the present study shows an interaction between factors secreted from EAT and the cardiomyocytes. Our data demonstrate that HFD feeding of guinea pigs induces specific alterations in the secretory profile of EAT that are responsible for the induction of contractile dysfunction and insulin resistance in primary adult rat cardiomyocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie-Adeline Marques (Inserm U858) and Janine Swifka (German Diabetes Center) for expert technical assistance, Peter Roesen (German Diabetes Center) for critical discussions and Birgit Hurow (German Diabetes Center) for excellent secretarial assistance. This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Innovation, Science, Research and Technology of the German State of North-Rhine Westphalia, the EU European Cooperation in the field of Scientific and Technical Research (COST) Action BM0602 (Adipose tissue: A key target for prevention of the metabolic syndrome) and the Commission of the European Communities (Collaborative Project ADAPT, contract no. HEALTH-F2–2008–201100).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Composition of the diets

Table S2 List of antibodies

Table S3 Immunoreactivity in conditioned medium collected from epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue explants from guinea pigs

Fig. S1 Effect of conditioned medium from epicardial andsubcutaneous adipose tissue on sarcomere shortening incardiomyocytes. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes were incubatedwith control AM or CM (diluted 1:2) from EAT and SAT from SD- andHFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. before analysis of contractilefunction. (A--C). Effect of exposure of cardiomyocytes to CMon departure velocity of contraction (A), peak sarcomereshortening (B) and return velocity of contraction(C). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; blackbars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ±S.E.M. of at least eight independent experiments. Differencesbetween the experimental groups were calculated by one-way ANOVAand unpaired Student's t-tests. #P <0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05, HFD versus SD;*P < 0.05; EAT versus SAT.

Fig. S2 Effect of conditioned medium from epicardial andsubcutaneous adipose tissue on cytosolic [Ca2+] incardiomyocytes. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes were incubatedwith control AM or CM (diluted 1:2) from EAT and SAT from SD- andHFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. before analysis of cytosolic[Ca2+]. (A--C) Effect of exposure ofcardiomyocytes to CM on [Ca2+] increase (A), peak[Ca2+] (B) and [Ca2+] decrease(C). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; blackbars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ±S.E.M. of at least eight independent experiments. Differencesbetween the experimental groups were calculated by one-way ANOVAand unpaired Student's t-tests. #P <0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05, HFD versus SD;*P < 0.05; EAT versus SAT.

Fig. S3 Contractile function in cardiomyocytes two hrsafter removal of CM. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes wereincubated with control AM or CM from EAT and SAT from SD- andHFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. Then, the CM were replaced bycontrol AM. Following a 2 hr incubation, contractile function andcytosolic [Ca2+] was analysed. (A--C)Reversibility effect of exposure of cardiomyocytes to CM ondeparture velocity of contraction (A), peak sarcomereshortening (B) and return velocity of contraction(C). (D--F) Reversibility effect of exposure ofcardiomyocytes to CM on [Ca2+] increase (D), peak[Ca2+] (E) and [Ca2+] decrease(F). Black bars: AM; grey bars: cells exposed to CM diluted1:4; open bars, cells exposed to CM diluted 1:4. Data are mean± S.E.M. from at least eight independent experiments. Groupswere compared by one-way ANOVA and unpaired Student'st-test. #P < 0.05 versus AM;*P < 0.05; HFD versus SD.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks HS, Fain JN. Human epicardial adipose tissue: a review. Am Heart J. 2007;153:907–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat: a review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabkin SW. Epicardial fat: properties, function and relationship to obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8:253–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouwens DM, Sell H, Greulich S, et al. The role of epicardial and perivascular adipose tissue in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2223–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacobellis G, Corradi D, Sharma AM. Epicardial adipose tissue: anatomic, biomolecular and clinical relationships with the heart. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2:536–43. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iacobellis G, Barbaro G. The double role of epicardial adipose tissue as pro- and anti-inflammatory organ. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:442–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1062724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker AR, Silva NF, Quinn DW, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue expresses a pathogenic profile of adipocytokines in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacobellis G, Pistilli D, Gucciardo M, et al. Adiponectin expression in human epicardial adipose tissue in vivo is lower in patients with coronary artery disease. Cytokine. 2005;29:251–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kremen J, Dolinkova M, Krajickova J, et al. Increased subcutaneous and epicardial adipose tissue production of proinflammatory cytokines in cardiac surgery patients: possible role in postoperative insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4620–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108:2460–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaldakov GN, Fiore M, Stankulov IS, et al. Neurotrophin presence in human coronary atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome: a role for NGF and BDNF in cardiovascular disease. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:279–89. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)46018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vural B, Atalar F, Ciftci C, et al. Presence of fatty-acid-binding protein 4 expression in human epicardial adipose tissue in metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:392–8. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fain JN, Sacks HS, Buehrer B, et al. Identification of omentin mRNA in human epicardial adipose tissue: comparison to omentin in subcutaneous, internal mammary artery periadventitial and visceral abdominal depots. Int J Obes. 2008;32:810–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karastergiou K, Evans I, Ogston N, et al. Epicardial adipokines in obesity and coronary artery disease induce atherogenic changes in monocytes and endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1340–6. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.204719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iacobellis G, di Gioia CR, Di Vito M, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue and intracoronary adrenomedullin levels in coronary artery disease. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:855–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1231081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamounier-Zepter V, Look C, Alvarez J, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein suppresses cardiomyocyte contraction: a new link between obesity and heart disease. Circ Res. 2009;105:326–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouwens DM, Boer C, Fodor M, et al. Cardiac dysfunction induced by high-fat diet is associated with altered myocardial insulin signalling in rats. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1229–37. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1755-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouwens DM, Diamant M, Fodor M, et al. Cardiac contractile dysfunction in insulin-resistant rats fed a high-fat diet is associated with elevated CD36-mediated fatty acid uptake and esterification. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1938–48. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0735-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swifka J, Weiss J, Addicks K, et al. Epicardial fat from guinea pig: a model to study the paracrine network of interactions between epicardial fat and myocardium. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2008;22:107–14. doi: 10.1007/s10557-008-6085-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moro C, Klimcakova E, Lolmede K, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits the production of adipokines and cytokines linked to inflammation and insulin resistance in human subcutaneous adipose tissue. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1038–47. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0614-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thalmann S, Juge-Aubry CE, Meier CA. Explant cultures of white adipose tissue. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;456:195–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-245-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckel J, Pandalis G, Reinauer H. Insulin action on the glucose transport system in isolated cardiocytes from adult rat. Biochem J. 1983;212:385–92. doi: 10.1042/bj2120385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ten Dijke P, Arthur HM. Extracellular control of TGFbeta signalling in vascular development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:857–69. doi: 10.1038/nrm2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchington JM, Pond CM. Site-specific properties of pericardial and epicardial adipose tissue: the effects of insulin and high-fat feeding on lipogenesis and the incorporation of fatty acids in vitro. Int J Obes. 1990;14:1013–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamounier-Zepter V, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Karczewski P, et al. Human adipocytes attenuate cardiomyocyte contraction: characterization of an adipocyte-derived negative inotropic activity. FASEB J. 2006;20:1653–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5436com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Periasamy M, Bhupathy P, Babu GJ. Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump expression and its relevance to cardiac muscle physiology and pathology. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:265–73. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebeche D, Davidoff AJ, Hajjar RJ. Interplay between impaired calcium regulation and insulin signaling abnormalities in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:715–24. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rijzewijk LJ, van der Meer RW, Lamb HJ, et al. Altered myocardial substrate metabolism and decreased diastolic function in nonischemic human diabetic cardiomyopathy: studies with cardiac positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1524–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouwens DM, Diamant M. Myocardial insulin action and the contribution of insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2007;113:76–86. doi: 10.1080/13813450701422633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwenk RW, Luiken JJ, Bonen A, et al. Regulation of sarcolemmal glucose and fatty acid transporters in cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:249–58. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palanivel R, Vu V, Park M, et al. Differential impact of adipokines derived from primary adipocytes of wild-type versus streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats on glucose and fatty acid metabolism in cardiomyocytes. J Endocrinol. 2008;199:389–97. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Brom CE, Huisman MC, Vlasblom R, et al. Altered myocardial substrate metabolism is associated with myocardial dysfunction in early diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats: studies using positron emission tomography. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1093–129. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maass DL, White J, Horton JW. IL-1beta and IL-6 act synergistically with TNF-alpha to alter cardiac contractile function after burn trauma. Shock. 2002;18:360–6. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A, Thota V, Dee L, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1beta are responsible for in vitro myocardial cell depression induced by human septic shock serum. J Exp Med. 1996;183:949–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weisensee D, Bereiter-Hahn J, Schoeppe W, et al. Effects of cytokines on the contractility of cultured cardiac myocytes. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1993;15:581–7. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(93)90075-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radin MJ, Holycross BJ, Dumitrescu C, et al. Leptin modulates the negative inotropic effect of interleukin-1beta in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;315:179–84. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yndestad A, Ueland T, Oie E, et al. Elevated levels of activin A in heart failure: potential role in myocardial remodeling. Circulation. 2004;109:1379–85. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120704.97934.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Florholmen G, Halvorsen B, Beraki K, et al. Activin A inhibits organization of sarcomeric proteins in cardiomyocytes induced by leukemia inhibitory factor. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:689–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirola L, Johnston AM, Van Obberghen E. Modulation of insulin action. Diabetologia. 2004;47:170–84. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaur K, Dhingra S, Slezak J, et al. Biology of TNFalpha and IL-10, and their imbalance in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2009;14:113–23. doi: 10.1007/s10741-008-9104-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhingra S, Sharma AK, Arora RC, et al. IL-10 attenuates TNF-alpha-induced NF kappaB pathway activation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:59–66. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damas JK, Gullestad L, Ueland T, et al. CXC-chemokines, a new group of cytokines in congestive heart failure–possible role of platelets and monocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:428–36. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourlier V, Bouloumie A. Role of macrophage tissue infiltration in obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:251–60. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:219–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bluher M. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117:241–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1192044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaragosi LE, Wdziekonski B, Villageois P, et al. Activin A plays a critical role in proliferation and differentiation of human adipose progenitors. Diabetes. 2010;59:2513–21. doi: 10.2337/db10-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Composition of the diets

Table S2 List of antibodies

Table S3 Immunoreactivity in conditioned medium collected from epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue explants from guinea pigs

Fig. S1 Effect of conditioned medium from epicardial andsubcutaneous adipose tissue on sarcomere shortening incardiomyocytes. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes were incubatedwith control AM or CM (diluted 1:2) from EAT and SAT from SD- andHFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. before analysis of contractilefunction. (A--C). Effect of exposure of cardiomyocytes to CMon departure velocity of contraction (A), peak sarcomereshortening (B) and return velocity of contraction(C). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; blackbars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ±S.E.M. of at least eight independent experiments. Differencesbetween the experimental groups were calculated by one-way ANOVAand unpaired Student's t-tests. #P <0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05, HFD versus SD;*P < 0.05; EAT versus SAT.

Fig. S2 Effect of conditioned medium from epicardial andsubcutaneous adipose tissue on cytosolic [Ca2+] incardiomyocytes. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes were incubatedwith control AM or CM (diluted 1:2) from EAT and SAT from SD- andHFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. before analysis of cytosolic[Ca2+]. (A--C) Effect of exposure ofcardiomyocytes to CM on [Ca2+] increase (A), peak[Ca2+] (B) and [Ca2+] decrease(C). Open bars: AM; grey bars: CM from SD-fed animals; blackbars: CM from HFD-fed animals. Data are expressed as mean ±S.E.M. of at least eight independent experiments. Differencesbetween the experimental groups were calculated by one-way ANOVAand unpaired Student's t-tests. #P <0.05 versus AM; *P < 0.05, HFD versus SD;*P < 0.05; EAT versus SAT.

Fig. S3 Contractile function in cardiomyocytes two hrsafter removal of CM. Primary adult rat cardiomyocytes wereincubated with control AM or CM from EAT and SAT from SD- andHFD-fed guinea pigs for 30 min. Then, the CM were replaced bycontrol AM. Following a 2 hr incubation, contractile function andcytosolic [Ca2+] was analysed. (A--C)Reversibility effect of exposure of cardiomyocytes to CM ondeparture velocity of contraction (A), peak sarcomereshortening (B) and return velocity of contraction(C). (D--F) Reversibility effect of exposure ofcardiomyocytes to CM on [Ca2+] increase (D), peak[Ca2+] (E) and [Ca2+] decrease(F). Black bars: AM; grey bars: cells exposed to CM diluted1:4; open bars, cells exposed to CM diluted 1:4. Data are mean± S.E.M. from at least eight independent experiments. Groupswere compared by one-way ANOVA and unpaired Student'st-test. #P < 0.05 versus AM;*P < 0.05; HFD versus SD.