Abstract

Uncontrolled release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) contributes to the reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte injury, e.g. hypercontracture and necrosis. To find out the underlying cellular mechanisms of this phenomenon, we investigated whether the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores (MPTP), resulting in ATP depletion and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, may be involved. For this purpose, isolated cardiac myocytes from adult rats were subjected to simulated ischemia and reperfusion. MPTP opening was detected by calcein release and by monitoring the ΔΨm. Fura-2 was used to monitor cytosolic [Ca2+]i or mitochondrial calcium [Ca2+]m, after quenching the cytosolic compartment with MnCl2. Mitochondrial ROS [ROS]m production was detected with MitoSOX Red and mag-fura-2 was used to monitor Mg2+ concentration, which reflects changes in cellular ATP. Necrosis was determined by propidium iodide staining. Reperfusion led to a calcein release from mitochondria, ΔΨm collapse and disturbance of ATP recovery. Simultaneously, Ca2+ oscillations occurred, [Ca2+]m and [ROS]m increased, cells developed hypercontracture and underwent necrosis. Inhibition of the SR-driven Ca2+ cycling with thapsigargine or ryanodine prevented mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS formation and MPTP opening. Suppression of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Ru360) or MPTP (cyclosporine A) significantly attenuated Ca2+ cycling, hypercontracture and necrosis. ROS scavengers (2-mercaptopropionyl glycine or N-acetylcysteine) had no effect on these parameters, but reduced [ROS]m. In conclusion, MPTP opening occurs early during reperfusion and is due to the Ca2+ oscillations originating primarily from the SR and supported by MPTP. The interplay between Ca2+ cycling and MPTP promotes the reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte hypercontracture and necrosis. Mitochondrial ROS formation is a result rather than a cause of MPTP opening.

Keywords: necrosis, cardiac myocytes, ischemia, sarcoplasmic reticulum, MPTP, reperfusion injury

Introduction

There is growing evidence that the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores (MPTP) significantly contributes to cardiomyocyte death in a reperfused myocardium, and that inhibition of MPTP in the early phase of reperfusion may prevent cell death and thus reduce infarct size [1–4]. The role of MPTP has also been confirmed in the clinical setting by the application of cyclosporine A at the time of reperfusion, a treatment that reduces infarct size and improves cardiac function in patients with acute myocardial infarction [4]. Although the contribution of MPTP for the reperfusion-induced myocardial injury has been intensively investigated [5, 6], the underlying cellular mechanism of MPTP opening in the early phase of reperfusion is still poorly understood. Within several cellular factors favouring the MPTP opening, mitochondrial/cytosolic Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to play an important role [6] and are elevated during ischemia and reperfusion in cardiac myocytes.

Previously we reported that spontaneous Ca2+ cycling occurs during the first 10 min. of reperfusion in cardiomyocytes [7]. These Ca2+ oscillations are due to a repetitive uptake and release of Ca2+ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Interventions directed to reduce the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations by interfering with the Ca2+ uptake or release can prevent the reperfusion-induced injury of cardiac myocytes [8, 9].

It has been also shown that under physiological conditions mitochondria actively reply to SR-mediated Ca2+ release by Ca2+ uptake due to anatomical proximity to SR organized in functional intracellular microdomains [10, 11]. Based on these data, we hypothesized that spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR may contribute to mitochondrial Ca2+ load during reperfusion, which thus may promote the MPTP opening resulting in a generation of mitochondrial ROS. Increased ROS generated by the mitochondria may in turn further aggravate the disturbance of Ca2+ handling within the cell [12]. Therefore, under pathological conditions, e.g. during reperfusion, an interplay between SR-Ca2+ release, mitochondrial MPTP opening and ROS formation may be supposed. Whether such interplay indeed occurs in cardiomyocytes during reperfusion and contributes to the reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte injury is still unknown. To examine this subject an in vitro model of simulated ischemia and reperfusion on isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes [7, 8] was applied. We found that reperfusion leads to a pathogenic interplay between SR-driven spontaneous Ca2+ cycling and MPTP opening. Interruption of this interplay protects cardiomyocytes against reperfusion-induced injury.

Materials and methods

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Experimental design

Cardiac myocytes were isolated from adult male Wistar rats as previously described [13]. Five hours after isolation, cardiac myocytes grown on glass cover-slips were introduced into a perfusion chamber (0.5 ml filling volume) and superfused at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The buffers were transferred into the perfusion chamber through gas-tight steel capillaries. To simulate ischemic conditions cells were exposed to simulated ischemia consisting of anoxia in combination with glucose-deprivation and acidosis (pH 6.4) as previously described [7]. After 10 min. of normoxic pre-incubation, cardiac myocytes were treated with ischemia for 80 min. followed by 20 min. reperfusion in glucose containing normoxic medium at pH 7.4. PO2 of ischemic buffer at the chamber outlet was less than 1.0 mmHg as determined by a polarographic oxygen sensor. A field with 6–10 rod shape cardiac myocytes was chosen for each experiment and condition. The perfusion chamber was mounted on a Microscope (Olympus IX-70, Hamburg, Germany) adapted to a Video-Imaging-System (Till Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany) – containing a light source (Polychrome V) on the excitation side, and a CCD Camera (Retiga 2000-RV, QImaging, Surrey, Canada) on the fluorescence detection side. Fluorescence data were analysed using TILLvisION Software (Till Photonics, Germany). The cell fluorescence was measured continuously every 6 sec. during the whole experiment. To detect the Ca2+ oscillations during reperfusion, the fura-2 signal was measured every 0.25 sec. in the reperfusion period.

The inhibitors of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Ru360, 1 μmol/l), SR-Ca2+ release (ryanodine, 5 μmol/l), SR-Ca2+ uptake (thapsigargine, 100 nmol/l), MPTP (cyclosporine A, 0.5 μmol/l) or oxygen radicals scavengers 2-mercaptopropionyl glycine (2-MPG, 100 μM) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 500 μmol/l) were administered 5 min. before and during reperfusion.

Determination of ΔΨm, cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+

ΔΨm was monitored by applying the fluorescence dye JC-1. For this purpose, cardiac myocytes were loaded with JC-1 (3 μmol/l) at 37°C for 20 min. and then washed for 20 min. The loaded cells were excited at 490 nm and the emitted fluorescence was collected at 530 nm and 590 nm. ΔΨm was expressed as the emitted fluorescence ratio (590/530 nm) in percentage to the initial level, whereas 0% level was found after complete mitochondrial depolarization with carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone.

To measure cytosolic Ca2+, cardiomyocytes were loaded at 37°C with fura-2 (5 μmol/l) for 30 min. and then washed for 20 min. To measure mitochondrial Ca2+, the fura-2 loaded cardiac myocytes were incubated in the presence of 50 μmol/l MnCl2 for 20 min. to quench the cytosolic fura-2. The cells were excited at 340, 360, 380 nm and the fluorescence emission was collected at 510 nm. [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m are presented as the ratio of fluorescence intensity resulting from excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm and expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Determination of MPTP opening

MPTP opening was determined by analyzing the mitochondrial calcein leak as previously described [14]. For this purpose, cardiac myocytes were incubated for 20 min. with calcein-AM (1 μmol/l) and then washed in presence of CoCl2 (1 mmol/l) for further 20 min. to quench the cytosolic compartment of the dye. During the whole experiments, the loaded cells were excited at 470 nm and the emitted light was collected at 510 nm. The sudden loss of calcein fluorescence was used as an indicator of the MPTP opening.

Determination of the cellular energetic state

Cellular ATP hydrolysis as well as resynthesis was monitored by measuring the intracellular Mg2+ concentration with the Mg2+-sensitive fluorescence indicator mag-fura-2 as previously described [15]. Briefly, cardiac myocytes were loaded with mag-fura-2 (5 μmol/l) at 37°C for 20 min. and then washed for 20 min. The mag-fura-2 loaded cells were excited alternately at 340 and 380 nm, and the fluorescence emission was collected at 510 nm. [Mg2+]i was expressed as the emission ratio resulting from excitation at 340 and 380 nm and expressed in a.u.

Mitochondrial ROS analysis

Mitochondrial ROS were monitored with MitoSOX Red, a mitochondrial superoxide fluorescence indicator. For this purpose, cells were loaded with 1 μmol/l MitoSOX Red at 37°C for 30 min. and then washed for 15 min. The loaded cells were excited at 510 nm and the emitted fluorescence was collected at 580 nm.

Determination of contracture and necrosis

Cell contracture was monitored by measuring the cell length during an entire experiment and expressed as a percentage of the cell length at the end of simulated ischemia. Necrosis was determined 30 min. after reperfusion by incubation of the cells with 30 μmol/l propidium iodide (PI) for 20 min.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as mean values ± S.E.M. from individual cells investigated in separate experiments. Statistical comparisons were performed by one-way anova followed by Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05.

Results

Cytosolic Ca2+ handling during reperfusion

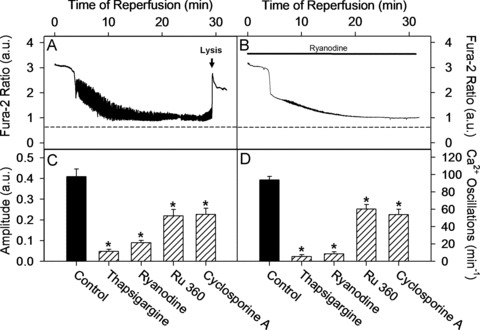

During the 80 min. of simulated ischemia, cardiac myocytes developed a cytosolic Ca2+ overload. Upon reperfusion, the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration transiently declined, but high-frequency Ca2+ oscillations occurred reaching a maximal frequency of 94 ± 6/min. between the 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion (Fig. 1A). Inhibition of the SR-Ca2+ uptake with thapsigargine or the SR-Ca2+ release with ryanodine abolished the spontaneous cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 1B). Similarly, treatment with cyclosporine A, an inhibitor of MPTP, or with Ru360, a blocker of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), significantly reduced the oscillation frequency (Fig. 1D). To exclude possible side effects of cyclosporine A or Ru360 on the SR-dependent Ca2+ transients, we applied these inhibitors also to electrically stimulated fura-2 loaded cardiac myocytes (1 Hz) under normoxic conditions. Neither cyclosporine A nor Ru360 influenced the kinetics of Ca2+ transients in electrically stimulated cells (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Inhibition of MPTP, MCU as well as SR Ca2+ uptake or release routes significantly attenuated spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations during cardiomyocyte reperfusion. (A–B) Single cell recordings of cytosolic fura-2 ratio (340/380 nm) during reperfusion under control conditions or under treatment with ryanodine. Dashed line represents pre-ischemic cytosolic fura-2 ratio at the beginning of ischemia. Arrow indicates the time of the fura-2 loss due to necrosis. (C) Maximal amplitude of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation defined between 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion in control cells or in cells treated during reperfusion with ryanodine (5 μmol/l), thapsigargine (100 nmol/l), Ru360 (1 μmol/l) or cyclosporine A (0.5 μmol/l). (D) Maximal oscillation frequency of cytosolic Ca2+ (min.−1) defined between 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion. Similar treatments as in (C). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 52–60 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control.

MPTP opening in simulated ischemia and reperfusion

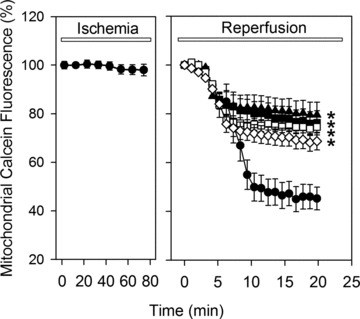

MPTP opening was monitored by two methods, i.e. by analyzing the cyclosporine A-sensitive mitochondrial calcein release and by cyclosporine A-sensitive changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ). A marked mitochondrial calcein loss occurred between the 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion, which was suppressed by cyclosporine A (0.5 μmol) (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Time course of the mitochondrial calcein fluorescence (in percentage to normoxic level) during 80 min. of ischemia and 20 min. of reperfusion in control cells (•) or in cells treated during reperfusion with 5 μmol/l ryanodine (♦), 100 nmol/l thapsigargine (◊), 1 μmol/l Ru360 (▪) or 0.5 μmol/l cyclosporine A (□). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 44–48 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control. Note that in control cells a dramatic loss of the calcein fluorescence was found between 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion indicating MPTP opening.

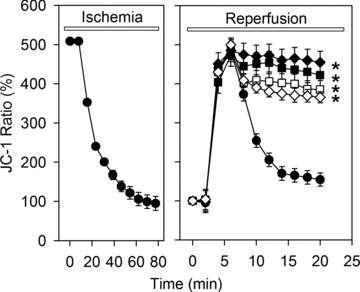

Because MPTP opening may cause a loss of the mitochondrial inner membrane potential (ΔΨm), we examined the effect of reperfusion on ΔΨm. In the absence of oxygen, i.e. under simulated ischemia, a gradual loss of ΔΨm was observed (Fig. 3). Reperfusion led to an initial transient recovery ΔΨm, which was followed by a rapid drop of ΔΨm between the 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion (Fig. 3). Similarly to calcein release, ΔΨm collapse was sensitive to cyclosporine A suggesting an involvement of MPTP opening.

Fig 3.

Time course of ΔΨ expressed as JC-1 fluorescence ratio (590/530 nm) during 80 min. of ischemia and 20 min. of reperfusion in control cells (•) or in cells treated during reperfusion with 5 μmol/l ryanodine (♦), 100 nmol/l thapsigargine (◊), 1 μmol/l Ru360 (▪) or 0.5 μmol/l cyclosporine A (□). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 44–50 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control. Values at the beginning of reperfusion were set to 100%. The decline of the JC-1 ratio represents mitochondrial membrane depolarization.

To examine the role of the SR and the mitochondrial Ca2+ handling in reperfusion induced MPTP opening, treatment with thapsigargine, ryanodine or Ru360 was applied. As shown in Figs 2 and 3, inhibition of the SR-Ca2+ uptake/release or mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake prevented the calcein leak from mitochondria and the collapse of ΔΨm in a manner comparable with direct inhibition of MPTP with cyclosporine A.

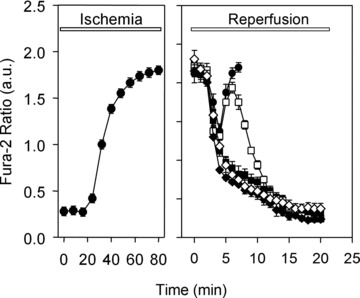

Role of mitochondrial Ca2+ overload for MPTP opening

Mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ load is an important trigger for the MPTP opening [6]. As shown in Fig. 4, simulated ischemia leads to an increase in [Ca2+]m, which transiently declines at the beginning of reperfusion before rising again during the first 10 min. of reperfusion in untreated control cells. The fura-2 ratio measurements of [Ca2+]m can only be followed within the first 6–8 min. of reperfusion. This is because at this time a dramatic drop of the fura-2 fluorescent signal in mitochondria was observed thus prohibiting the proper estimation of the fura-2 emission ratio. This fura-2 signal loss may be due to Mn2+ influx into the mitochondria, e.g. through MPTP, which quenches the fura-2 signal. Indeed, treatment with cyclosporine A prevented the loss of fura-2 signal, indicating a possible role of MPTP. Therefore, in the control group the fura-2 ratio is presented in Fig. 4 only until the point of the massive fura-2 signal loss.

Fig 4.

Time course of the mitochondrial calcium concentration indicated by fura-2 fluorescence ratio (340/380 nm) in the presence of MnCl2 (to bleach the fluorescence of cytosolic fura-2) during 80 min. of ischemia and 20 min. of reperfusion in control cells (•) or in cells treated during reperfusion with 5 μmol/l ryanodine (♦), 100 nmol/l thapsigargine (◊), 1 μmol/l Ru360 (▪) or 0.5 μmol/l cyclosporine A (□). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 48–55 cells from five different preparations. The rise of the fura-2 ratio represents the increase of the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration.

To test whether SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ handling is involved in the secondary increase in [Ca2+]m, experiments were carried out in the presence of thapsigargine, ryanodine or Ru360 during reperfusion. As shown in Fig. 4, treatment with thapsigargine and ryanodine prevented the rise in [Ca2+]m in reperfused cardiomyocytes. In contrast, treatment with cyclosporine A did not abolish the secondary rise of [Ca2+]m. Nevertheless, the blockade of MPTP with cyclosporine A supported a delayed recovery of the mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis.

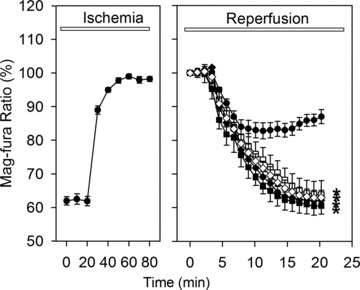

Energy state during ischemia and reperfusion

Reactivation of the mitochondrial function, i.e. ATP synthesis, upon reperfusion may be disturbed by MPTP opening resulting in cell death. To investigate this point, ATP hydrolysis as well as resynthesis was indirectly monitored during simulated ischemia and reperfusion by analysing the intracellular Mg2+ concentration with the fluorescent dye mag-fura-2 [15] (Fig. 5). Indeed, simulated ischemia led to an increase in Mg2+-concentration indicating the degradation of ATP. During the initial reperfusion phase, Mg2+-concentration declined as a result of cellular ATP resynthesis, but ceased between the 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion. Treatment with thapsigargine, ryanodine, cyclosporine A or Ru360, promoted a further decline of the Mg2+-concentration, suggesting a preservation of the ATP resynthesis.

Fig 5.

Time course of cellular Mg2+-concentration measured by mag-fura-2 fluorescence ratio (340/380 nm) during 80 min. of ischemia and 20 min. of reperfusion in control cells (•) or in cells treated during reperfusion with 5 μmol/l ryanodine (♦), 100 nmol/l thapsigargine (◊), 1 μmol/l Ru360 (▪) or 0.5 μmol/l cyclosporine A (□). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 44–48 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control. Values at the beginning of reperfusion were set to 100%. The rise of the mag-fura-2 ratio represents the increase of the intracellular Mg2+ concentration.

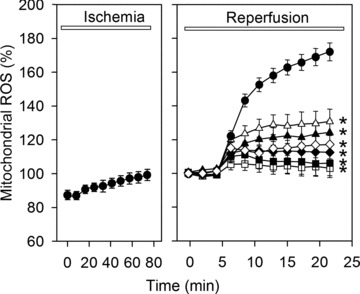

Mitochondrial ROS formation during ischemia and reperfusion

Because ROS may significantly contribute to the MPTP opening during ischemia and reperfusion, we addressed the role ROS in our model applying the mitochondria targeted superoxide fluorescent indicator MitoSOX Red. Ischemia alone led to a slight increase in MitoSOX fluorescence, whereas reperfusion induced a marked ROS formation during the initial phase of reperfusion (Fig. 6). This increase in MitoSOX fluorescence was abolished by treatment with ROS scavengers 2-MPG (100 μM) or NAC (500 μM). Similarly, a treatment with the SR-inhibitors thapsigargine or ryanodine, with the MPTP-inhibitor cyclosporine A or with the MCU-inhibitor Ru360 prevented the rise in MitoSOX fluorescence, suggesting that mitochondrial ROS formation is a result of Ca2+ oscillation induced MPTP opening. In contrast, both ROS scavenges had no effects on the reperfusion induced Ca2+ oscillations, mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, mitochondrial calcein leak and ΔΨm. (data not shown).

Fig 6.

Time course of mitochondrial ROS measured as MitoSox fluorescence during 80 min. of ischemia and 20 min. of reperfusion in control cells (•) or in cells treated during reperfusion with 5 μmol/l ryanodine (♦), 100 nmol/l thapsigargine (◊), 1 μmol/l Ru360 (▪), 0.5 μmol/l cyclosporine A (□), 100 μmol/l 2-MPG (▴) or 500 μmol/l NAC (▵). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 44–48 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control. Values at the beginning of reperfusion were set to 100%.

Cell contracture and necrosis during reperfusion

During the reperfusion period cardiac myocytes developed a severe contracture during the first 5 to 10 min. of reperfusion, i.e. during the oscillation phase of cytosolic Ca2+. On average, they shortened up to 40% of their length prior to reperfusion. As shown in Fig. 7A, the presence of the SR-Ca2+-uptake inhibitor thapsigargine or the SR-Ca2+-release inhibitor ryanodine significantly reduced the observed contracture. In the presence of cyclosporine A or Ru360, development of contracture was also significantly attenuated. In contrast, treatment with ROS scavengers NAC and 2-MPG did not influence reperfusion-induced cell shortening.

Fig 7.

Inhibition of MPTP, MCU and SR Ca2+ uptake or release routes significantly reduced reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte hypercontracture and necrosis. (A) Length of cardiac myocytes after 20 min. of reperfusion (in percentage to end-ischemic length) under control conditions or in the presence of 5 μmol/l ryanodine, 100 nmol/l thapsigargine, 1 μmol/l Ru360, 0.5 μmol/l cyclosporine A, 100 μmol/l 2-MPG or 500 μmol/l NAC. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 50–55 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control. (B) Cell necrosis after 30 min. of reperfusion defined by PI staining and expressed as a percentage of the total cell count. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 200–300 cells from five different preparations. *P < 0.05 versus control.

As observed before, in the absence of external forces the hyper-contracted cells initially retained their sarcolemmal integrity [16]. This is why a recovery of Ca2+ control can be monitored even in hypercontracted cardiac myocytes during the initial phase of reperfusion. After about 30 min. of reperfusion, however, a necrotic cell death occurs, which was determined by the fura-2 leak and by an increase in the membrane permeability to PI. Without additional treatment, i.e. in control group, about 65% cells were PI positive after 80 min. ischemia followed by 30 min. reperfusion (Fig. 7B). All these cells invariably demonstrated a fura-2 leak. Treatment with ryanodine, thapsigargine, cyclosporine A or Ru360 significantly reduced the number of necrotic cells. Again, the treatment with ROS scavengers, NAC or 2-MPG, had no effect on the necrotic cell death.

Discussion

The principal findings of the study are the following: (i) In cardiac myocytes exposed to simulated ischemia-reperfusion MPTP opening occurs during the first minutes of reperfusion; (ii) MPTP opening is triggered by a secondary mitochondrial Ca2+ overload caused by SR-driven Ca2+ oscillations; (iii) MPTP opening promotes Ca2+ oscillations; (iv) Both, SR-driven Ca2+ oscillation and MPTP opening contribute to the ROS formation, mitochondrial dysfunction, cardiomyocyte hypercontracture and necrosis; (v) ROS formation is a result rather than a cause of MPTP opening and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Restoration of blood flow with the aim to protect cardiomyocytes against ischemic death may itself lead to the cell death within the first minutes of reperfusion in the form of necrosis. The pathological hallmark of reperfusion-induced necrosis is the presence of contraction bands, reflecting cardiomyocyte hypercontracture [16, 17]. Energy-dependent hypercontracture contributes to cell death, as demonstrated by studies in which pharmacological inhibition of contractility at the onset of reperfusion reduced infarct size [18, 19]. Within several mechanisms responsible for the reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte hypercontracture, spontaneous high amplitude transients of cytosolic Ca2+ during the first minutes of reperfusion has been shown to play a key role [7–9]. In the present study, we further investigated the underlying cellular mechanism linking Ca2+ oscillations with hypercontracture. Particularly, applying different techniques (calcein leak, [Ca2+]m and ΔΨm measurements) we demonstrated the central role of MPTP opening in Ca2+ oscillation induced hypercontracture and cell death.

It has been suggested that mitochondrial Ca2+ overload is an important cause for MPTP opening in various cell types [7]. In the present study, a mitochondrial Ca2+ overload was found at the end of the simulated ischemia. During the first minutes of reperfusion, mitochondria resumed respiration and a transient decline of mitochondrial Ca2+ was observed. However, [Ca2+]m rose again within 5th and 10th min. of reperfusion until the MPTP opening occurred. In line with previous reports suggesting the MCU as a main route for mitochondrial Ca2+ influx in cardiomyocytes [10], inhibition of MCU with Ru360 in the present study abolished the secondary [Ca2+]m rise. Furthermore, blockade of the MCU also prevented MPTP opening, confirming the previously demonstrated role of [Ca2+]m overload for MPTP opening [6]. Interestingly, a blockade of MPTP opening by cyclosporine A did not prevent the secondary rise in mitochondrial Ca2+, but allowed cells to recover the [Ca2+]m homeostasis. All together, these data support the hypothesis that SR-driven Ca2+ cycling during the initial phase of reperfusion jeopardizes recovery of mitochondrial [Ca2+]m homeostasis resulting in MPTP opening and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Because cytosolic Ca2+ cycling is a physiological event in functional cardiomyocytes, it is surprising that during reperfusion these spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations may lead to a mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and MPTP opening. It has been shown that the SR-mitochondria communication occurs through anatomical and functional intracellular microdomains [10, 11, 20]. Furthermore, mitochondrial calcium uptake is more dependent on Ca2+ concentration within these microdomains around the contact sites of mitochondria with SR than on cytosolic Ca2+ concentration [11]. Finally, SR-mediated calcium propagation to mitochondria persists even after cytosolic Ca2+ is chelated with 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) in permeabilized cardiac myocytes [20]. Altogether, these findings suggest that the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake may be activated by the exposure of MCU to the local high calcium concentration within the microdomains independently of the level of cytosolic Ca2+. Under physiological conditions, such interplay between SR and mitochondria plays a crucial role for coupling energy demand with mitochondrial ATP production [21]. However, during reperfusion, when mitochondria are already Ca2+ overloaded, the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake promoted by SR-mediated Ca2+ release within the SR-mitochondria microdomains may disturb the recovery of [Ca2+]m homeostasis and trigger MPTP opening finally resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction.

The relationship between SR-driven calcium oscillations and MPT appears to be bidirectional. In the present study, inhibition of MCU with Ru360, or MPTP with cyclosporine A, significantly attenuated the SR-dependent Ca2+ oscillations in reperfused myocardial cells. These inhibitors of mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes had no effect on cytosolic Ca2+ cycling in electrically stimulated control cardiac myocytes in which severe mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and MPTP opening is not expected. Thus, MPTP-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ release is part of the oscillatory mechanism for Ca2+ shifts in the reperfused myocardial cells. Because the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations play a key role in reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte hypercontracture [8], suppression of MPTP in the present study either by Ru360 or by cyclosporine A also significantly reduced the hypercontracture.

Additionally to hypercontracture, a cardiomyocyte necrosis was found 30 min. after reperfusion, which was also strongly dependent on Ca2+ cycling. This effect of Ca2+ cycling on cell necrosis seems to be due to the collapse of ΔΨm followed by ATP depletion observed in the present study.

Aside from the ATP depletion, a formation of ROS has been suggested as a cause of the necrotic cell death [22]. Our data indicate that ROS indeed are generated early during reperfusion. All agents used to interfere with Ca2+ cycling, thus limiting mitochondrial Ca2+ load, or those used to interfere directly with MPTP opening (cyclosporine), reduced ROS generation in a manner comparable to that of the antioxidants NAC and 2-MPG. However, prevention of the ROS formation by treatment with antioxidants had no effect on the reperfusion-induced cell death. Similarly, ROS had no effect on Ca2+ cycling and MPTP opening. Therefore, for the model described here, we conclude that reperfusion-induced ROS formation is a result rather than a cause for Ca2+ cycling or MPTP opening.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate an interplay between SR-dependent Ca2+ cycling and MPTP. They both are important parts of the reperfusion-induced mechanism responsible for SR-cytosol Ca2+ shifts, which jeopardize the reperfused myocardial cells promoting hypercontracture and cell necrosis. Further research for novel tools specifically interrupting this interplay may provide a new strategy to protect cardiac tissue against reperfusion-induced injury.

Acknowledgments

The technical help of S. Kechter, G. Pfeiffer, D. Schreiber and O. Becker is gratefully acknowledged. This work is part of a thesis submitted by M. Said in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Medicine at the Justus-Liebig-Universität, Giessen. This work was supported by Grant AB380/1-1 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by Forum Grant F660-2009 of the Ruhr-University Bochum.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Halestrap AP, Clarke SJ, Javadov SA. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening during myocardial reperfusion–a target for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:372–5. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausenloy DJ, Duchen MR, Yellon DM. Inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening at reperfusion protects against ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakagawa T, Shimizu S, Watanabe T, et al. Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature. 2005;434:652–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piot C, Croisille P, Staat P, et al. Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:473–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halestrap AP. What is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:821–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruiz-Meana M, Fernandez-Sanz C, Garcia-Dorado D. The SR-mitochondrial interaction: a new player in cardiac pathophysiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:30–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladilov YV, Siegmund B, Piper HM. Protection of reoxygenated cardiomyocytes against hypercontracture by inhibition of Na+/H+ exchange. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1995;268:H1531–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegmund B, Schlack W, Ladilov YV, et al. Halothane protects cardiac myocytes against reoxygenation-induced hypercontracture. Circulation. 1997;96:4372–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdallah Y, Gkatzoflia A, Pieper HM, et al. Mechanism of cGMP-mediated protection in a cellular model of myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duchen MR, Leyssens A, Crompton M. Transient mitochondrial depolarizations reflect focal sarcoplasmic reticular calcium release in single rat cardiac myocytes. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:975–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szalai G, Csordas G, Hantash BM, et al. Calcium signal transmission between ryanodine receptors and mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15305–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camello-Almaraz C, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Pozo MJ, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C1082–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00217.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piper HM, Probst I, Schwartz P, et al. Culturing of calcium stable adult cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1982;14:397–412. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(82)90171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Lisa F, Blank PS, Colonna R, et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential in single living adult rat cardiac myocytes exposed to anoxia or metabolic inhibition. J Physiol. 1995;486:1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyssens A, Nowicky AV, Patterson L, et al. The relationship between mitochondrial state, ATP hydrolysis, [Mg2+]i and [Ca2+]i studied in isolated rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1996;496:111–28. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Dorado D, Theroux P, Duran JM, et al. Selective inhibition of the contractile apparatus: a new approach to modification of infarct size, infarct composition, and infarct geometry during coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Circulation. 1992;85:1160–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki S, Fujiwara H, Onodera T, et al. Quantitative analysis of contraction band and coagulation necrosis after ischemia and reperfusion in the porcine heart. Circulation. 1987;75:1074–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumida T, Otani H, Kyoi S, et al. Temporary blockade of contractility during reperfusion elicits a cardioprotective effect of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB-203580. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2726–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01183.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tani M, Hasegawa H, Suganuma Y, et al. Protection of ischemic myocardium by inhibition of contracture in isolated rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2515–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma VK, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C, et al. Transport of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria in rat ventricular myocytes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2000;32:97–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1005520714221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maack C, Cortassa S, Aon MA, et al. Elevated cytosolic Na+ decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during excitation- contraction coupling and impairs energetic adaptation in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;99:172–82. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000232546.92777.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Krysko DV, et al. Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology of necrotic cell death. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:207–20. doi: 10.2174/156652408784221306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]