Abstract

The intensive care unit (ICU), where death is common and even survivors of an ICU stay face the risk of long-term morbidity and re-admissions to the ICU, represents an important setting for improving communication about palliative and end-of-life care. Communication about the goals of care in this setting should be a high priority since studies suggest that the current quality of ICU communication is often poor and is associated with psychological distress among family members of critically ill patients. This paper describes the development and evaluation of an intervention designed to improve the quality of care in the ICU by improving communication among the ICU team and with family members of critically ill patients. We developed a multi-faceted, interprofessional intervention based on self-efficacy theory. The intervention involves a “communication facilitator” – a nurse or social worker – trained to facilitate communication among the interprofessional ICU team and with the critically ill patient’s family. The facilitators are trained using three specific content areas: a) evidence-based approaches to improving clinician–family communication in the ICU, b) attachment theory allowing clinicians to adapt communication to meet individual family member’s communication needs, and c) mediation to facilitate identification and resolution of conflict including clinician–family, clinician–clinician, and intra-family conflict. The outcomes assessed in this randomized trial focus on psychological distress among family members including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder at 3 and 6 months after the ICU stay. This manuscript also reports some of the lessons that we have learned early in this study.

Keywords: Communication, Palliative care, Critical care, Randomized trial

1. Background

The intensive care unit (ICU) represents an important setting for improving communication about palliative and end-of-life care because death is common and because patients are at high risk for both mortality and long-term morbidity [1-3]. Palliative care issues may be raised by critical illness even for patients who survive the ICU and for their family members because of underlying chronic life-limiting illness or sequellae of their critical illness [4]. Furthermore, because the cultural orientation of the ICU is one of saving lives [5,6], effective communication about palliative and end-of-life care and alternative goals of care can be difficult [7]. The ICU is an important setting for improving communication about the goals of care since studies suggest that the current quality of communication is often poor: family members are more dissatisfied with communication than other domains of care [8,9] and physicians are often unaware of patients’ wishes regarding palliative and end-of-life care [10,11].

A number of studies have tested communication interventions in the ICU with the goal of improving patient and family outcomes. One of the earliest and most extensive of these efforts was the SUPPORT study, a multi-million dollar randomized trial funded primarily by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The SUPPORT intervention used research nurses who provided quantitative prognostic estimates to patients, families, and physicians; obtained treatment preferences from patients and families providing this information to physicians; and scheduled a meeting between physicians, patients and families [11]. SUPPORT was conducted by experienced health services researchers in the fields of critical care and end-of-life care, yet the intervention did not improve care [11]. There have been a number of suggestions as to why this intervention was unsuccessful including: a) the intervention did not provide specific direction for physicians regarding the conduct of communication with patients and families; b) the intervention focused on individual physicians and patients and did not attempt to change the communication within the team; c) the research nurses were not integrated into the clinical team; and d) the outcome measures may not have been sensitive to important changes [12,13]. An intervention to improve the quality of end-of-life care must incorporate these lessons from SUPPORT.

Since the conclusion of SUPPORT, a number of studies have suggested that interventions to improve clinician–family communication in the ICU can result in improved quality of care. A multi-center randomized trial examined the effect of a routine ethics consultation for patients “in whom value-related treatment conflicts arose” [14]. These ethics consultations, which focused on improving communication as well as addressing ethical dilemmas, reduced the number of days that patients spent in the ICU prior to death. This finding suggests a reduction in the prolongation of dying. In addition, families and clinicians reported a high level of satisfaction with the ethics consultation, although satisfaction was not compared with the group randomized to usual care. In a before-after study design, routine palliative care consultation reduced the number of ICU days prior to death for patients with anoxic encephalopathy after cardiac arrest or patients with multiple organ failure and another study showed similar effect for patients with advanced dementia [15,16]. Other studies, both before–after designs and randomized trials, have also suggested the benefit of ethics or palliative care consultation in the ICU [16-18]. In combination, these studies suggest that interventions using an interprofessional team to improve clinician communication with families can improve the quality of care that patients receive. However, an important limitation of this prior research is that the precise way that communication can be improved is unclear and was left to the judgment of the clinical ethicist [14,17,18], palliative care specialist [15,16], or ICU physician [19].

In 2007, a landmark study from France showed that a relatively simple communication intervention resulted in dramatic reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among family members 3 months after a death in the ICU [20]. Although this study represents an important advance, a number of factors limit its implementation in the US. First, given the differences in communication with families between the US and France, it is impossible to know whether the intervention would have a similar effect in the US [21]. For example, baseline rates of interprofessional family conferences are much lower in France than in many areas of the US. Second, patients became eligible when physicians were confident the patient would die, which is often relatively late in the ICU stay. Third, a communication intervention may also improve care for seriously ill patients who survive as well as for their family members. For instance, recent studies suggest that family members of patients that survive the ICU are at risk for anxiety, depression and PTSD and are more critical of the care their loved one received than are family members of decedents [8,22,23]. These families and their patients may therefore also benefit from improved communication.

Our goal was to develop and test an intervention designed to improve palliative and end-of-life care in the ICU by improving communication among the ICU team and family members of critically ill patients. In this paper, we describe the theoretical foundation and development of a multi-faceted, interprofessional intervention as well as the design of a study to evaluate the intervention (NCT00720200). We also report some of the lessons learned in the conduct of this study.

2. Theoretical foundation for the intervention

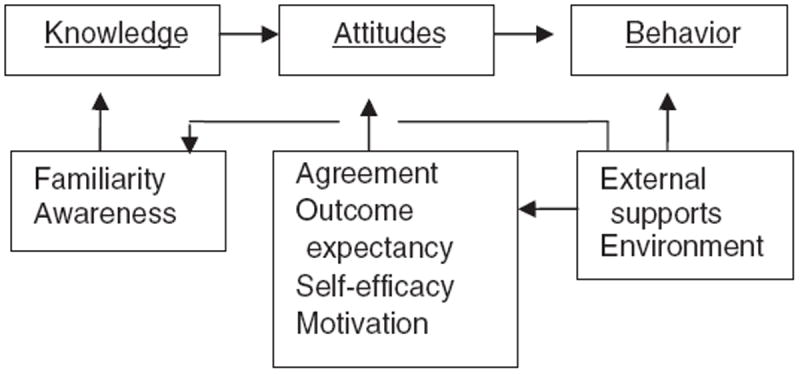

This intervention was based on self-efficacy theory [24-26] which has been used to guide interventions for changing a wide range of health [27,28] and clinician behaviors [29-31]. In this theory, the impetus for change resides in the individual’s efficacy expectations, that is, his/her “confidence in his/her ability to take action and persist in action.” [25] Although primarily an individual-specific construct, self-efficacy does not arise out of the individual alone but develops in part from the interaction and experience of the individual with the environment (e.g. hospital, ICU). This paradigm for understanding behavior change has been applied to clinician behavior to explain the empirical data on clinical guideline implementation (see Fig. 1) [29]. In this framework, aspects of efficacy expectations including familiarity, awareness, agreement, outcome expectancies, and motivation are associated with clinicians’ willingness to adopt guidelines. These researchers also identified external supports related to environmental and organizational factors that facilitate the implementation of clinical guidelines [29]. Finally, the framework suggests that these efficacy expectations result in three components of measureable outcomes that influence change: knowledge, attitudes and behavior.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical framework for the development of the intervention.

3. Overview of the study

This study is a clustered randomized trial of a “communication facilitator” intervention designed to improve communication and decision-making among physicians, nurses, and families for patients who are critically ill and in the ICU. Eligible patients are critically ill and unable to participate in clinical decision-making and are randomly assigned to either the intervention or a “usual care” control group. Communication facilitators assist families of patients in the intervention group, identifying questions and issues of concern and providing communication support during the ICU stay. Control group participants complete questionnaires and all other study procedures but do not have the assistance of a facilitator. The primary outcome is a measure of family members’ symptoms of depression, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Secondary outcomes include symptoms of PTSD using the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL), and symptoms of anxiety using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7). These measures are assessed 3 and 6 months after the patient dies or is discharged from the ICU alive. Among patients dying in the ICU, we measure the quality of dying as assessed by families and ICU nurses.

4. Description of the intervention

The intervention uses a communication facilitator to increase families’ and clinicians’ self-efficacy expectations about communication in the ICU. We operationalized the three components that were conceptualized as important contributors to behavior change in the following ways: 1) the knowledge component uses a growing literature on patient–family–clinician communication techniques founded in empirical data in ICU settings and linked with positive family and patient outcomes; [32] 2) the attitude component is derived from principles of attachment theory; [33,34] and 3) the behavior component is based on principles of mediation applied to the healthcare setting [35,36].

4.1. Knowledge: evidence-based communication about end-of-life care in the ICU

There is a growing body of knowledge about clinician–family communication in the ICU based on empirical studies and expert opinion. In a series of studies examining ICU family conferences, we defined the general content and outline of communication during these conferences and identified the range of communication styles and behaviors that clinicians use to provide emotional support for family members [37]. We also identified specific features of this communication that are associated with increased family satisfaction including: 1) an increase in the proportion of time during the conference that the family speaks; [38] 2) a focus on potential missed opportunities, such as the opportunity to listen and respond to family members; 3) the opportunity to acknowledge and address family emotions; and 4) the opportunity to address basic tenets of palliative care including the exploration of patients’ preferences, principles of surrogate decision-making, and assuring non-abandonment [39]. Additionally, we identified specific statements providing emotional support that were associated with family satisfaction including assurances that the patient will not suffer and support for families’ decisions about end-of-life care [40]. We also showed that basic expressions of empathy by clinicians were associated with increased family satisfaction with communication [41]. Finally, we developed and tested the mnemonic “VALUE” (valuing family statements, acknowledging emotion, listening, understanding the patient as a person, eliciting questions) showing that an intervention using this approach was associated with decreased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among family members after the death of a loved one in the ICU. [20] In addition, Pochard and colleagues found a number of features of communication with the family that are associated with fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression among family members including consistent communication by ICU clinicians and finding a private place for family communication [23].

These studies provide an evidence base upon which we built the knowledge component of the intervention. The communication facilitators were trained to use these features of communication in discussions with family members and to facilitate use of these components by members of the ICU clinical team.

4.2. Attitudes: attachment theory

Collaborative communication that includes optimal exchange of information, values and emotional content between clinicians, patients and family members is associated with improved outcomes in end-of-life care [20,42,43]. However, there is significant interpersonal variability in capacity or willingness of individuals to collaborate with or rely on others in the clinical setting [44]. Even with the best efforts of individual clinicians, healthcare teams or systems of care, communication may often be sub-optimal when interpersonal styles of patients or family members are not taken into consideration. Attachment theory provides a means of understanding and working with individuals’ capacities or preferences for communicating with or relying upon others. Evoked under stressful situations (particularly anticipated loss), attachment or relationship styles are cognitive schemas or “maps” that determine an individual’s perceptions and attitudes when engaging with others around emotionally-laden issues (e.g. critical illness). Empirical data from over thirty years has shown that there are four distinct attachment style categories, three of which may be challenging in difficult decision-making circumstances, and may require greater attention and special communication skills. These problematic relationship styles pertain to about 45% of the population [45]. For example, individuals with a predominantly “self-reliant” relationship style (25% of the general population) may be reluctant to ask questions or participate collaboratively in decision-sharing in stressful situations. Such individuals may benefit from being given options and from feeling in charge of a situation. Conversely, individuals with a predominantly “support-seeking” relationship style (10% of the general population) typically have high emotional needs that may be inadequately addressed in complex and harried hospital environments. They may benefit from regularly scheduled and consistent communication. Individuals with a “cautious” relationship style (10% of the general population) may exhibit approach-avoidance behavior under stressful circumstances and, when their initial attempts at collaborating or asking questions are perceived as falling short, they may then abandon further attempts out of fear of relying on others for support. They may benefit from efforts to build trust and encourage regular communication. These three relationship styles not only influence the capacity of individuals to engage with members of a clinical team, but may also significantly influence their ability to process anticipated loss [46].

Attachment styles have been used to influence perception and quality of communication in healthcare settings. In patients with diabetes being treated for depression, attachment style is associated with satisfaction with care and with perceived quality of communication with their physician [47]. Attachment style is also an important predictor of the quality of patient–clinician communication and a predictor of the influence of this communication on health outcomes including glycosylated hemoglobin levels [44].

Using this theory to understand family members’ individual needs may help ICU clinicians alter their attitudes and, consequently, their communication in ways that may improve clinician–family communication. We are using a brief, validated measure of attachment styles [48]. The facilitators use the results from this measure to provide information to clinicians with the goal of altering clinician attitudes toward individual family members that will support: 1) increasing understanding of the emotional needs and interactive styles of family members; 2) developing tailored approaches for engaging family members in meaningful discussions around palliative and end-of-life care; and 3) determining anticipatory grief needs of family members.

4.3. Behavior: mediation

Decision-making in the ICU is often characterized by conflicts that not only include therapeutic decisions, but also extends to other issues including communication styles, interpersonal interactions, and symptom control [49-51]. A prospective study of ICU patients for whom withdrawal of life support was considered reported conflicts occurring between staff and family in 48% of cases, among staff in 48% of cases, and among family members in 24% of cases [50]. Improved communication about goals, prognoses, and treatment options may successfully resolve conflicts and minimize unrealistic expectations by families [52,53]. Formal incorporation of the established body of knowledge and principles of mediation into the healthcare setting is a useful way to systematically address and resolve conflict, thereby improving communication as well as patient and family outcomes [35,54,55]. Our intervention specifically targets all three of the following types of conflict: staff-family, staff-staff, and family-family. Facilitators trained in mediation may be able to identify the source of conflict and establish lines of communication among these different parties. Mediation skills most relevant to this intervention include summarizing, reframing, avoiding unwarranted assumptions, identifying and framing issues neutrally, acknowledging feelings, asking clarifying questions to draw out underlying needs and interests, and packaging proposals [36,56]. The principles of transformative mediation [57] are of particular relevance to family members and clinicians engaged in making decisions about end-of-life care; they suggest that conflict results in individuals feeling confused and unable to see perspectives other than their own. Mediation is an opportunity to change the quality of those conflictual interactions empowering individuals to both express their own perspectives and collaborate in finding shared decisions.

5. Training the facilitators

The facilitators are individuals with nursing or social work backgrounds. We chose these specialists because they commonly have training in communication and interpersonal skills as well as an understanding of the hospital environment upon which our facilitator training is built. In addition, by using nurses or social workers rather than individuals with psychology or mediation backgrounds, we hope to increase the generalizability of the intervention; nurses and social workers are more likely to be available on hospital staff than psychologists or mediators.

Training was provided in all three components and includes: 1) for knowledge, facilitators reviewed existing evidence and expert opinion in the area of interprofessional communication in the ICU setting (described above, 4.1); 2) for attitudes, facilitators developed an understanding of the different types of attachment (relationship) styles, the consequences of these styles for interpersonal relationships, and the types of communication approaches that will be most appropriate for these styles; and 3) for behavior, mediation training covered six steps of the mediation process: assessment and preparation; mediator opening; presentation of the case, information gathering and exchange; development and evaluation of options; and resolution. Because mediation in hospital settings requires adaptations to accommodate the limits and requirements of these settings, facilitators received training in the special characteristics associated with bioethical mediation, including discussion of such topics as: hospital affiliation, limits on confidentiality, education in ethical and societal standards, and assistance with implementation of resolution [36]. In addition, “shuttle mediation” was implemented as a means for sharing perspectives among all stakeholders when it was not possible to arrange meetings that included everyone.

Facilitators participate in both didactic and role-playing exercises and are required to demonstrate sufficient mastery of the required skills as determined by the trainers with expertise in each of the three components. We are developing a manual to enhance generalizability of the training. After the initial training, facilitators meet regularly with investigators at least quarterly to review intervention cases and confirm that the intended skills and strategies are being faithfully implemented.

6. Study design and implementation

6.1. Study design

This study is a randomized trial of an interprofessional, multi-faceted intervention of a communication facilitator. Subjects are identified from ICUs in Seattle-area hospitals, including academic and community-based sites. Eligible patients are critically ill and unable to participate in decision-making, requiring surrogate decision-making. Based on our eligibility criteria, we anticipate approximately 30–40% of the eligible patients will die in the ICU. Patients are randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. Communication facilitators assist families of patients in the intervention group. Control group participants complete questionnaires but do not have the assistance of a facilitator.

The study’s aims include the following: 1) to evaluate the efficacy of a facilitator-assisted interprofessional communication intervention in the ICU on families’ psychological symptoms at 3 and 6 months after the ICU stay; 2) to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention on patients’ quality of dying and death as evaluated by families and nurses; and 3) to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention on processes of care and processes of communication. The study’s success in achieving these aims is assessed using multiple outcome and process measures (Table 1). The primary outcome measure is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [58], a measure of family members’ symptoms of depression at 3 months after death or discharge from the ICU. We also collect outcome data at 6 months to examine longer-term effect of the intervention. Secondary outcome measures include the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) [59], a measure of symptoms of PTSD, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) survey, a measure of family member’s symptoms of anxiety [60,61]. These measures are collected 3 and 6 months after the patient leaves the ICU. Among patients dying in the ICU, the Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire is completed by families and nurses [62]. Among all patients, we also evaluate the effect of the intervention on: 1) length of stay in the ICU and hospital; and 2) costs during an ICU stay including estimated costs of the intervention.

Table 1.

Study measures and data collection protocol.

| Measures | Concept | Source | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major outcome measures | ||||

| Psychological distress in family members | ||||

| PHQ-9 [58] | Family symptoms of depression | Families | Yes | Yes |

| PCL [59] | Family symptoms of PTSD | Families | Yes | Yes |

| GAD-7 [61] | Family symptoms of anxiety | Families | Yes | Yes |

| Processes of care | ||||

| Length of stay | Length of time in the ICU and hospital | Medical chart | No | Yes |

| Costs of care | Estimated costs of medical care and of the intervention | Hospital decision support | No | Yes |

| Key covariate measures | ||||

| Chart review | Patient demographics, diagnosis, chronic health conditions, illness severity; indicators of palliative care | Medical chart | No | Yes |

| Demographic questionnaire | Family: age, gender, education, insurance, income, relationship to patient | Families | Yes | No |

6.2. Implementation of the intervention and control

Patients are randomized at enrollment, after their families consent to study participation. Randomization is stratified by hospital to assure equal proportions of intervention and control patients across hospitals. Group assignment is determined with computerized random numbers generated by a statistician and provided to study staff in sealed, opaque, consecutively-numbered envelopes.

Regardless of group assignment, study staff distribute baseline questionnaires to all participating family members and also contact all family members by phone at the time of the follow-up questionnaires to notify them that questionnaires are being sent to them and ask if they have any questions. These contacts through study staff are designed to enhance response rates for both groups [63]. For the control group, these contacts with study staff are conducted as “friendly visits” and provide an “attention control.” [64].

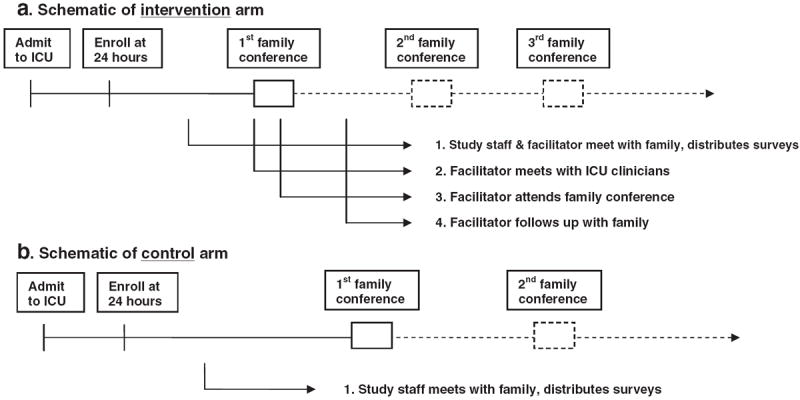

The intervention includes the following steps: 1) in-person interviews by the facilitator with the family in order to better understand and discuss the family’s concerns, questions, needs and unique communication characteristics; 2) in-person meetings by the facilitator with physicians, nurses, or other clinicians in which a brief summary describing the family’s concerns, questions, needs, and unique communication characteristics is discussed; 3) provision of emotional support in a manner most likely to complement the family member’s attachment style; 4) facilitator participation in family conferences when possible; and 5) facilitator follow-up with the family throughout the ICU stay and at discharge to acute care.

Fig. 2 shows a schematic of the timeline of the intervention and control arms for an individual patient and family. A component of the facilitator’s role also includes helping identify the need for a family conference and helping schedule these conferences.

Fig. 2.

a: Schematic of intervention arm. b: Schematic of control arm.

7. Participant eligibility and recruitment

7.1. Patients

Study staff screen ICU census daily in order to identify all ICU patients meeting the following criteria: 1) in the ICU for >24 h; 2) older than 18; 3) mechanically ventilated at time of enrollment; 4) having a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score ≥ to 8 or diagnostic criteria that predicts a ≥50% risk of hospital mortality; [65,66] 5) a legal surrogate decision-maker to consent for patient participation, and 6) a family member able to come to the hospital.

None of the eligible patients have decisional capacity at the time of enrollment and patients are not approached directly to provide consent for the intervention. Consent is provided by the patient’s legal surrogate decision-maker. If the patient of an enrolled family develops decisional capacity during the ICU stay, as determined by the treating physician, the intervention will end and the patient will be approached for consent for use of data already collected or to be collected as part of the study. Family members may continue to participate in the outcomes evaluation of the study, regardless of the patient’s participation status.

7.2. Family members

Families of eligible patients are contacted initially by the bedside ICU nurse and provided a study flyer. The nurse asks the legal surrogate decision-maker if he or she is willing to talk with study staff. If the patient has a domestic partner or close friend that is not recognized as the legal surrogate decision-maker by state law, this person is also included, provided the legal surrogate decision-maker does not object. All persons included in this process, up to a total of six per patient, are offered the opportunity to participate in the study if they choose to do so.

8. Study measures

8.1. Outcome measures

8.1.1. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Families’ symptoms of depression, as measured by the PHQ-9, is the primary outcome and will be assessed both at baseline and at the 3 and 6 month follow-up. This 9-item questionnaire is widely used, is appropriate for both primary care and general populations [58] and has demonstrated excellent psychometric characteristics including: internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86–0.89); test–retest reliability (ricc =0.81–0.96); sensitivity (ROC=0.95); and specificity (ROC=0.84) [67,68]. The PHQ-9 has been validated against diagnostic interviews conducted by mental health professionals and higher scores predict decreased functional status, increased disability days, and increased health care use [69]. Importantly, the PHQ-9 has demonstrated good responsiveness in a naturalistic study of depression [70], a randomized trial of a stepped-collaborative intervention [68], and several behavioral interventions for depression [68,71-75].

8.1.2. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Civilian Version (PCL)

The PCL uses 17 self-report items to assess the intrusive, avoidant, and arousal DSM-IV PTSD symptom clusters. The measure can be scored continuously or for symptoms consistent with the DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD [76]. The measure has well established reliability and validity across trauma-exposed populations [59,77-79]. Among parents of hospitalized injured teens, the measure demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.93) [80]. In a study of injured motor vehicle crash survivors, a cutoff score of 45 or greater had a sensitivity of 0.95 and specificity of 0.86 when compared to the gold standard diagnostic interview [59]. It has also demonstrated responsiveness in a randomized trial of stepped collaborative care for trauma survivors [81]. Because of its established reliability, validity and responsiveness across trauma exposed populations, as well as the continuous and dichotomous DSM IV PTSD scoring algorithms, the PCL yields advantages over other PTSD assessment instruments that have been previously employed in the follow-up of ICU families (Impact of Events Scale [20,22]) or patients (Post Traumatic Stress Scale [82,83]).

8.1.3. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a measure of generalized anxiety disorder and provides an additional secondary measure. In a criterion-standard study of 15 primary care clinics with 2740 adult patients, the GAD-7 self-report scale demonstrated excellent psychometric characteristics including: internal-consistency reliability (Cronbach alpha=0.92), test–retest reliability (ricc =0.83); sensitivity (ROC=0.92); specificity (ROC= 0.76); and factorial validity (factor loadings=0.69–0.81) [61]. Higher scores on the GAD-7 were associated with higher levels of functional impairment, more disability days and more physician visits [60,61]. GAD-7 has been shown to be responsive to behavioral interventions [72,84-86].

8.2. Process measures

8.2.1. Length of stay

ICU length of stay has been shown to be a responsive measure for communication interventions in the ICU. It has been included in a number of studies, many of which have shown reductions in length of stay. These interventions include: 1) ethics consultations [18]; 2) palliative care consultation [15,16]; 3) comfort care order form implementation; [87] and 4) implementation of daily goals and routine family meetings [19,88,89].

8.2.2. Costs of care

We will estimate costs of care for patients based on hospital charges (using “micro-costing” methods) times the hospital-specific “ratio of costs to charges” assessed by Medicare. Although hospitals vary in methods for assessing charges, this will not affect internal validity for a randomized trial. In addition, we will estimate the costs of care associated with the intervention by collecting data on the time spent by the facilitator in the provision of services related to the delivery of the intervention (using clinical nurse specialist wages) and excluding time spent on research activities. Although costs of care in the ICU track closely with ICU days [90,91], this cost accounting will allow us to assess costs savings associated with the intervention while accounting for the costs of the intervention.

9. Data collection

9.1. Surveys for family members

Family members complete a baseline survey at the time of study enrollment, which is provided to them by study staff and returned in-person or by mail to the project office. A post-intervention follow-up survey is mailed to families’ homes 3 and 6 months after a patient dies in the ICU or after the patient is discharged alive from the ICU. These surveys are returned to the project office in a postage-paid return envelope or may be completed by phone with study staff.

9.2. Chart abstraction

In order to guarantee the reliability and validity of the chart abstraction data, we use standardized methods for training and quality control [92-94]. Data abstractors undergo at least 80 h of training including instruction on the protocol, guided practice charts, and independent chart review followed by reconciliation with a trainer. Questions and problems with interpretation are discussed and practice abstraction continues until 90% agreement with the trainer is achieved. A 5% random sample of all patient records are dual-abstracted. Chart abstractors are blinded to randomization and survey results.

10. Analysis plan

10.1. Overview of analytic approach

The patient is the unit of randomization and the randomization group (intervention or control) is the primary predictor of interest. Because family members are clustered under patients for many of the analyses, we need to account for the lack of independence in observations through the use of mixed-effects random-coefficient regression modeling. We will conduct the primary analyses using data from all family members who participate in the study guided by the principle that we should not arbitrarily pick one family member [95]. However, we will also conduct secondary analyses using unclustered regression models, identifying one family member for each patient based on the hierarchy identified by Washington State law for surrogate decision-making.

The mixed-effects random-coefficient regression approach adjusts standard errors to appropriately correct for correlated observations and can also accommodate repeated measures and longitudinal data [96-98]. Additionally, while randomization should make the use of covariates or confounding variables unnecessary, we will utilize pre-randomization assessments of patient and family characteristics that may help reduce variability unrelated to the intervention and result in an increase in the precision of the estimates.

10.2. Sample size estimates

We have based sample size estimates on the primary outcome, the PHQ-9. Because sample size requirements are the largest for the clustered analyses and the primary analyses are clustered, we estimated sample sizes for those analyses. For the PHQ-9, we will need a total of 350 family members (175 per group). Estimates are based on the following: 1) an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.44; [99] 2) an average cluster size of 3, assuming an average of 3 families per patient; c) an effect size of 0.20 based on the PHQ-9’s demonstrated minimally clinically important difference of 5 on a 27 point scale [68]; 4) alpha of 0.05; and 5) power of 0.80.

11. Study progress and lessons learned

The study began enrolling patients in 1/13/2009 and, as of 6/12/2012, we have enrolled 143 patients and 251 family members. We opted not to conduct any interim analyses of quantitative outcome data in order to preserve a p value of 0.05 for hypothesis testing of the primary outcome. However, we have conducted qualitative analyses of comments on returned surveys from family members randomized to the intervention. We examined all 145 such comments, of which 22 were about the facilitator. Of these 22 comments, 21 were positive, 1 was neutral, and none were negative. Table 2A shows a selection of the comments, providing anecdotal support for the intervention. In addition, Table 2B shows some comments about transitions after the ICU, which are not addressed in the ongoing study, but may be a target for future interventions.

Table 2.

Example comments provided by enrolled family members to open-ended questions on the family surveys.

| A: Example comments made about the ICU facilitator

|

| I have very much appreciated talking to the ICU facilitators for this study. I have found being able to speak with them invaluable on a personal level as well as giving me important information about other resources available. As a result of my conversations with them, I have reached out for other services that have helped me have better conversations with the doctors providing care for my wife. |

| I appreciate the facilitator so much. She was very supportive and helped me cope with my daughter’s medical problems. |

| Dear facilitator: Thanks so much for being such a great support to me and my family during such a hard time. Having you there during that last meeting where I walked out and having your support during that time was so great. |

| I felt the facilitator was a tremendous help in helping navigate some things re: care and processes. I am a nurse and my husband is a physician, so being in a hospital setting was not stressful. But being on “the other side” was. |

| B: Example comments made about transitions after the ICU

|

| ICU time was honestly the best of the time for my husband’s care management. Acute care where patients go if they leave the ICU was terrible, inconsistent, dangerous and depressing. More needs to be done for families that transfer to this care level. |

| The problem I had with the hospital happened after she left ICU. They just sent her home in a taxi with little warning and no support. |

| I’m surprised to realize I am under more stress now (than in the ICU). My son (the patient) is having a difficult time. This has spilled over to the family. Do you or someone follow up with ICU patients after discharge? |

In the conduct of this study to date, we have identified four primary lessons learned. First, one of the major challenges in a research study like this is to embed the communication facilitator within the clinical team. Since our communication facilitators are funded by the grant and not employed by the hospitals, it has required particular efforts to have them identified by clinicians as a part of the clinical team. Second, we attempted to identify patients with a 50% risk of hospital mortality. Using severity scores to identify this subgroup, a significant proportion of these patients died before we were able to enroll the patients and their family. In order to ensure adequate enrollment, we broadened our entry criteria to enable us to identify patients with a slightly smaller mortality risk (30%). Third, since many family members visit critically ill patients in the evenings, we found we had to extend the hours of the communication facilitators to be able to provide the intervention to family members. Fourth, we have learned that an important target for communication facilitation is after patients are discharged from the ICU and from the hospital. As shown in Table 2B, family members often reported that communication breakdowns were more common and serious after ICU discharge.

12. Potential limitations

12.1. Respondent bias in an unblinded study

The nature of the intervention precludes blinding clinicians or family members. The primary outcome measure in this study addresses the hypothesis that we will reduce family symptoms of depression. Secondarily, we hope to reduce family symptoms of anxiety and PTSD as well as improve ratings on the QODD. These outcomes are inherently subjective and therefore could allow the introduction of bias if the family members who received the intervention give different ratings because they want to please or support the facilitator, not because the intervention improved their experiences. Although this is a potential limitation, we believe it is unlikely to have an important effect on the results of this study for two reasons. First, family members are surveyed 3 and 6 months after the patient’s death or discharge from the ICU. In this time period, they will not have contact with the facilitator and therefore it seems unlikely that their responses will be influenced by a desire to please or support the facilitator. Second, family members randomized to the control group will receive an “attention control” that may mitigate this potential bias. Nonetheless, since it is not possible to blind the intervention and since family members will assess the primary outcomes, it is important to acknowledge this inherent potential limitation.

12.2. Contamination of the control group

Because the patient, not the clinician, is the unit of randomization, physicians and nurses may participate in the care of patients randomized to both intervention and usual care. This raises the possibility that there may be some “contamination” of the intervention by clinicians who have participated in the intervention but are also providing care for patients randomized to usual care. We believe this is unlikely to have a major effect on the results because prior research has shown that improving palliative and end-of-life care in the ICU is difficult [11,100]. We believe that the intervention will require the individualized and family-specific activities provided by the facilitator in order to be successful. Although we will not be able to control for this potential contamination, we will look for an improvement in outcomes in the control group over the course of the study as a potential way to identify a contamination effect. Finally, because all of these ICUs have received basic education in palliative care as a result of our prior studies, a contamination effect simply by clinician education is less likely [100,101].

12.3. Baseline palliative care knowledge and practice in the study hospitals

One potential limitation is that the study will take place in hospitals that previously participated in an educational and quality improvement intervention [100,101]. This is a potential threat to generalizability. However, recent advances in palliative and end-of-life care in the ICU have led many hospitals and ICUs to implement educational and quality improvement programs on this topic [4,102]. The fact that our study sites have all undergone some education make it more likely that the control group will receive the currently accepted “standard of care” for palliative care in the ICU, yielding results from this proposed trial that are more, rather than less, generalizable to the standard of care when this study is completed.

13. Significance and anticipated results

Given that 20% of deaths in the U.S. occur in or shortly after a stay in the ICU and that the quality of decision-making and communication for families of critically ill patients is variable and often poor, this is an important area for research [4]. There is growing evidence that an intervention that focuses on improving interprofessional communication within the ICU team and with patients’ family can significantly improve the quality of palliative care for patients and their families, but to date there are limited well-described and generalizable interventions that can be easily implemented by hospitals and ICUs. This randomized trial proposes to test a carefully described and implemented intervention to improve ICU care with a particular focus on facilitating decision-making through enhanced, patient-focused and family-centered communication. We anticipate showing effectiveness of the intervention compared to usual care, as defined by reduced symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress among family member. Family comments about the communication facilitator on surveys suggest that the facilitator is appreciated by family members, but we have not completed data collection or examined the results of this study. This study, regardless of the outcome, will provide important information that will have the potential to lead to significant improvements in the care received by critically ill patients and their families.

Footnotes

Funding: Funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01 NR05226).

Trial Registration: Registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00720200).

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hough CL, Curtis JR. Long-term sequelae of critical illness: memories and health-related quality of life. Crit Care. 2005;9:145–6. doi: 10.1186/cc3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyland DK, Hopman W, Coo H, Tranmar J, McColl MA. Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3599–605. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet. 2010;376:1347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caswell D, Omrey A. The dying patient in the intensive care unit: making the critical difference. Clin Issues Crit Care Nurs. 1990;1:178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson JE. Saving lives and saving deaths. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:776–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-9-199905040-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danis M, Federman D, Fins JJ, et al. Incorporating palliative care into critical care education: principles, challenges, and opportunities. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2005–13. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wall RJ, Curtis JR, Cooke CR, Engelberg RA. Family satisfaction in the ICU: differences between families of survivors and nonsurvivors. Chest. 2007;132:1425–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1413–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patients’ preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995;274:1591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo B. Improving care near the end of life: why is it so hard? JAMA. 1995;274:1634–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynn J, Arkes HR, Stevens M, et al. Rethinking fundamental assumptions: SUPPORT’s implications for future reform. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S214–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123:266–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. A proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical intensive care unit for patients with terminal dementia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1839–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000138560.56577.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowdy MD, Robertson C, Bander JA. A study of proactive ethics consultation for critically and terminally ill patients with extended lengths of stay. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:252–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD. Impact of ethics consultations in the intensive care setting: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3920–4. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200012000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–75. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luce JM, Lemaire F. Two transatlantic viewpoints on an ethical quandary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:818–21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.cc0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37:122–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strecher VJ, DeVellis BE, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1986;13:73–91. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patrick DL, Grembowski DE, Durham M, et al. Cost and outcomes of medicare reimbursement for HMO preventive services. Health Care Financ Rev. 1999;20:25–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabana MD, Rushton JL, Rush AJ. Implementing practice guidelines for depression: applying a new framework to an old problem. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care. A new measure and new insights. Med Care. 1990;28:724–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134:835–43. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ciechanowski PS, Walker EA, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Attachment theory: a model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:660–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021948.90613.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ. The interpersonal experience of health care through the eyes of the patient with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:3067–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubler NN. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005;(Spec No):S19–25. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2005.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubler NN, Liebman CB. Bioethics Mediation: A Guide to Shaping Shared Solutions. New York: United Hospital Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17:147–60. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2002.35929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the ICU: Increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1484–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:844–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;43:1679–85. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218409.58256.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selph RB, Shiang J, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, White DB. Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1311–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Walker EA. The patient–provider relationship: attachment theory and adherence to treatment in diabetes. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:29–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciechanowski PS, Worley LL, Russo JE, Katon WJ. Using relationship styles based on attachment theory to improve understanding of specialty choice in medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan A, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Interpersonal processes in palliative care: an attachment perspective on the patient–clinician relationship. Palliat Med. 2005;19:143–50. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm994oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciechanowski PS, Russo JE, Katon WJ, et al. The association of patient relationship style and outcomes in collaborative care treatment for depression in patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2006;44:283–91. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199695.03840.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffin D, Bartholomew K. The metaphysics of measurement: the case of adult attachment. Adv Pers Relat. 1994;5:17–52. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbott KH, Sago JG, Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Tulsky JA. Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:197–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Abbott KH, Tulsky JA. Conflict associated with decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:283–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the Conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:853–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1614OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goold SD, Williams BC, Arnold RM. Handling conflict in end-of-life care. JAMA. 2000;283:909–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Medical futility in end-of-life care: Report of the Council on ethical and judicial affairs. JAMA. 1999;281:937–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubler N. Limiting technology in the process of negotiating death. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2001:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dubler NN. Mediating disputes in managed care: resolving conflicts over covered services. J Health Care Law Policy. 2002;5:479–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gold J. Advanced Mediation Manual: Using a Faciltative Approach. Washington DC: Washington Legal Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baruch Bush RA, Folger JP. The Promise of Mediation. Jossey Bass, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC, et al. Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously-ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med. 2006;20:745–54. doi: 10.1177/0269216306073112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwartz CE, Chesney MA, Irvine MJ, Keefe FJ. The control group dilemma in clinical research: applications for psychosocial and behavioral medicine trials. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:362–71. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kajdacsy-Balla Amaral AC, Andrade FM, Moreno R, Artigas A, Cantraine F, Vincent JL. Use of the sequential organ failure assessment score as a severity score. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:243–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peres Bota D, Melot C, Lopes Ferreira F, Nguyen Ba V, Vincent JL. The Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS) versus the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score in outcome prediction. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1619–24. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:131–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42:1194–201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81:61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richards DA, Borglin G. Implementation of psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in routine practice: two year prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lowe B, Schenkel I, Carney-Doebbeling C, Gobel C. Responsiveness of the PHQ-9 to Psychopharmacological Depression Treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:62–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:706–13. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4488–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) 4. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marshall GN, Schell TL. Reappraising the link between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptom severity: evidence from a longitudinal study of community violence survivors. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:626–36. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Muller HG, et al. Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:941–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zatzick D, Russo J, Grossman DC, et al. Posttraumatic Stress and Depressive Symptoms, Alcohol Use, and Recurrent Traumatic Life Events in a Representative Sample of Hospitalized Injured Adolescents and Their Parents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:371–87. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of stepped collaborative care for acutely injured trauma survivors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:498–506. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schelling G, Stoll C, Hallar M, et al. Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute respiratory distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:651–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schelling G, Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, et al. The effect of stress doses of hydrocortisone during septic shock on posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in survivors. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2678–83. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, et al. Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40:216–27. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zou JB, Dear BF, Titov N, et al. Brief internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in older adults: a feasibility trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:650–5. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Titov N, Andrews G, Johnston L, Robinson E, Spence J. Transdiagnostic Internet treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:890–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hall RI, Rocker GM, Murray D. Simple changes can improve conduct of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:631–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03018408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, Lipsett PA, Simmonds T, Haraden C. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care. 2003;18:71–5. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2003.50008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lilly CM, Sonna LA, Haley KJ, Massaro AF. Intensive communication: four-year follow-up from a clinical practice study. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S394–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065279.77449.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rapoport J, Teres D, Lemeshow S, Avrunin JS, Haber R. Explaining variability of cost using a severity-of-illness measure for ICU patients. Med Care. 1990;28:338–48. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199004000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rapoport J, Teres D, Lemeshow S, Gehlbach S. A method for assessing the clinical performance and cost-effectiveness of intensive care units: a multicenter inception cohort study. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1385–91. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199409000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Glavan B, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1138–46. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gries CJ, Wall RJ, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision-making in the ICU. Chest. 2008;133:704–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. A comparison of responders and non-responders to a survey of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit (abstract) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:A63. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burt RA. Law’s effect on the quality of end-of-life care: lessons from the Schiavo case. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S348–54. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237270.55658.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zucker DM. An analysis of variance pitfall: the fixed effects analysis in a nested design. Educ Psychol Meas. 1990;50:731–8. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:43–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Osborne ML, Engelberg RA, Ganzini L. Agreement among family members in their assessment of the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:306–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, et al. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:348–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:269–75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld LA, et al. End-of-life care for the critically ill: a national intensive care unit survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2547–53. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]