Abstract

Approximately 20% of individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD) report a positive family history. Yet, a large portion of causal and disease-modifying variants is still unknown. We used exome sequencing in two affected individuals from a family with late-onset familial PD followed by frequency assessment in 975 PD cases and 1014 ethnically-matched controls and linkage analysis to identify potentially causal variants. Based on the predicted penetrance and the frequencies, a variant in PLXNA4 proved to be the best candidate and PLXNA4 was screened for additional variants in 862 PD cases and 940 controls, revealing an excess of rare non-synonymous coding variants in PLXNA4 in individuals with PD. Although we cannot conclude that the variant in PLXNA4 is indeed the causative variant, these findings are interesting in the light of a surfacing role of axonal guidance mechanisms in neurodegenerative disorders but, at the same time, highlight the difficulties encountered in the study of rare variants identified by next-generation sequencing in diseases with autosomal dominant or complex patterns of inheritance.

Introduction

Characterized by resting-tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability, Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most prominent neurodegenerative disorders. Genetic factors contribute significantly to the risk of developing PD–both sporadic and familial. Although up to 20% of PD cases are believed to be familial [1], [2], thus far, variants in only a few genes have been unequivocally shown to underlie familial PD. These include PARK2, PINK1, PARK7, SNCA, and LRRK2 [3]–[8]. While all of these genes were identified by classical linkage analysis in large, multi-generation families, recently, next-generation sequencing has enabled the identification of disease-causing variants in smaller families and with an onset later in life without the need of genotypic information from more than one generation of affected individuals. By exome sequencing, VPS35 was identified as a gene involved in late-onset familial PD [9], [10]. Still, to date, the identified genes only explain a small portion of the genetic “burden” in PD. However, a thorough understanding of the genetic alterations implicated in disease development is necessary to better comprehend disease pathogenesis and to provide more specific and, thus, more effective treatment options in the future.

Here, we describe exome sequencing of a German family with autosomal dominant late-onset PD in an attempt to pinpoint the disease-causing genetic variant.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Ethics review board approval was obtained from the ethics review board at Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, and Bayerische Landesärztekammer, both Munich, Germany, Hessische Landesärztekammer, Frankfurt, Germany, the ethics review board at Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria, and the ethics review board at Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary. Participants’ written informed consent was obtained.

Participants

All living family members received a detailed neurologic exam by neurologists specializing in movement disorders. Cases and controls used in genotyping and variant screening have been reported previously [10], [11] and are described in more detail in the supplement.

Exome Sequencing

Exome sequencing was performed with DNA isolated from lymphozytes of IV:11 and IV:18 on a Genome Analyzer IIx system (Illumina) after in-solution enrichment of exonic sequences (SureSelect Human All Exon 38 Mb kit for IV:11 and 50 Mb kit for IV:18, Agilent) as 76 bp paired-end runs. Read alignment was carried out with BWA (version 0.5.8). Single-nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions (indels) were detected with SAMtools (version 0.1.7). Raw sequencing data are available upon request.

Genotyping

All ten candidate variants tested for segregation by Sanger sequencing were genotyped in 975 cases and 1014 population-based controls pertaining to the KORA-AGE cohort using MALDI-TOF masspectrometry on the Sequenom® platform. Demographic data are given in the supplement. Association was tested by allelic statistics as implemented in PLINK.

Linkage Analysis

We genotyped six family members (IV:11, IV:14, IV:16, IV:18, IV:20 and IV:21) with oligonucleotide SNP arrays (500 K, Illumina). Parametric linkage analysis was performed using a subset of 12,875 SNPs using MERLIN and an autosomal dominant model with incomplete penetrance of 70%.

Variant Screening

We used Idaho®’s LightScanner high-resolution melting curve analysis to screen the coding regions and exon/intron boundaries of PLXNA4 for variants. 862 cases and 940 population-based controls pertaining to the KORA-AGE cohort were included in the screening. Demographic data are given in the supplement. In the case of an altered melting pattern, Sanger sequencing ensued to identify the underlying variant. Group comparisons between cases and controls were performed for each gene and each variant separately using Fisher’s Exact and χ2 tests as appropriate.

Cell Viability and Immunocytochemistry

Cultured primary fibroblasts from IV:11 and an offspring were stained using a live/dead staining (Invitrogen) and analyzed by FACS and stained with anti-PLXNA4 (1∶100, Sigma) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Details are given in the supplement.

Construction of a Qualitative Systems Biological Model

To investigate the role of PLXNA4 in the PD biological system, we applied an integrative modeling approach to construct a qualitative multifactorial interaction network linking PLXNA4 and genetic factors associated with PD. An interactome with known and predicted interactions of PLXNA4 and its direct neighbors was prepared based on four commonly used databases and integrated to known PD pathways from KEGG and CIDeR as well as a manual literature search. For a detailed description see supplement.

Results

Pedigree and Clinical Phenotype

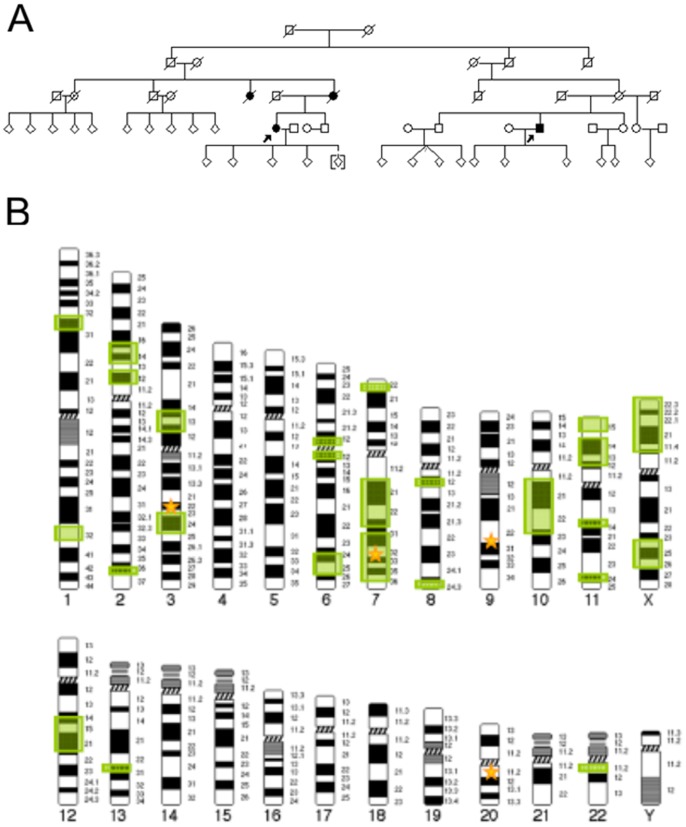

We describe a five-generation family from Central Germany in which four members were affected by PD and the pattern of inheritance seems to be autosomal dominant with reduced penetrance (Figure 1). Clinical assessment revealed tremor-dominant, levodopa-responsive parkinsonism with an age of onset at 60 and 67 years of age in the two affected individuals examined (Table S1 in File S1). Both individuals also reported subjective cognitive impairment. Restless legs syndrome was present in IV:11 as well as one of her children. Transcranial ultrasound showed bilateral hyperechogenicity of the substantia nigra in IV:18 but was not performed in IV:11. MRI was in line with a diagnosis of PD in both. The affected parent (III:7) and aunt (III:5) of IV:11 were deceased before initiation of the study, so that no detailed phenotype information is available. Moreover, another aunt (III:2) on the same side of the family was reported to have suffered from an unclassified form of dementia.

Figure 1. Pedigree and Linkage Analysis.

(A) Pedigree of family used for exome sequencing. Open symbols indicate unaffected family members, affected individuals are denoted by closed symbols. An arrow denotes the individuals whose exomes were sequenced. Sex was obscured and birth order was altered to protect privacy. A diagonal line indicates a deceased individual. (B) 25 genomic regions on 12 chromosomes with logarithm of the odds (LOD) score≥0.5 were identified by linkage analysis. Green boxes represent genomic regions with LOD≥0.5, yellow stars represent the location of the four candidate genes remaining after frequency assessment (GOLGA4-chr3, PLXNA4-chr7, OGN-chr9, CPNE1-chr20). PLXNA4 on chromosome 7 represents the only of the four genes overlapping a genomic region with LOD≥0.5.

Identification of Candidate Variants by Exome Sequencing and Frequency Assessment of Candidate Variants in a Case/Control Cohort

Exome sequencing was performed using DNA from two second cousins (IV:11 and IV:18, Figure 1A). This generated 11.68 gigabases (Gb) of alignable sequence for IV:11 (average coverage = 108.46, base pairs with >8 reads = 93.67%) and 15.02 Gb for patient IV:18 (average coverage = 154.13, base pairs with >8 reads = 94.74%). All 28,803 detected variants shared by the two affected individuals were filtered against in-house exomes (n = 1739) of individuals with unrelated diseases. Here, variants were allowed to be present in ≤1% of exomes. Moreover, synonymous and non-coding variants as well as all variants annotated in dbSNP135 with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.01 were excluded from the follow-up (Figure S1). No known variants believed to play a causative role in PD were found in either IV:11 or IV:18.

All ten remaining missense, nonsense, stoploss, splice site or frameshift variants and indels were genotyped in 975 cases and 1014 population-based controls (Table 1). The variants were, overall, very rare. Two (PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn and OGN p.Leu124fs) were validated in the individual in whom they were first identified but were otherwise not found again in the 1989 individuals tested. CPNE1 p.Ser1831Thr was present in the index case as well as one additional control individual and GOLGA4 p.Gln425Arg was identified in one additional PD patient. The other six variants (RBM28 p.Asp300Gly, IMPDH1 p.His296Arg, ARPP21 p.Ala576Thr, PHF2 p.Ser840Asn, SLC22A13 p.Arg16His and SPANXE p.Leu42Ile) were not as rare (MAF≥0.03%) and found at similar frequencies in both cases and controls and were, therefore, regarded to be unlikely candidates (Table 1).

Table 1. Ten Rare, Non-synonymous Variants Shared by Individuals IV:11 and IV:18 of Family PARK_0005.

| Genomicposition (hg19) | gene | number of alleles | in house exomes (n = 1739) | genotyping | dbSNP135 | 1000genomes | NHLBI-ESP [39] (EA only) | transcript | variation | penetrance for PD in % (n = 6) | PolyPhen2 | ||

| cases (n = 975) | controls (n = 1014) | nucleotide | amino acid | ||||||||||

| chr3∶35780947 | ARPP21 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 11 | rs151173813 | 0.0031∶2218 | A = 37/G = 8563 | NM_001267617.1 | c.1726G>A | p.Ala576Thr | N/A | benign |

| chr3∶37365968 | GOLGA4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | rs139536585 | not found | G = 8/A = 8592 | NM_001172713.1 | c.1274A>G | p.Gln425Arg | 66.67% | benign |

| chr7∶127950857 | RBM28 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | rs148028531 | 0.0007∶14795 | C = 20/T = 8580 | NM_018077.2 | c.2273T>C | p.Asp758Gly | 40.00% | poss. damaging |

| chr7∶128037009 | IMPDH1 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 5 | rs61751223 | 0.0052∶2280 | C = 23/T = 8577 | NM_000883.3 | c.887T>C | p.His296Arg | 40.00% | benign |

| chr7∶131910932 | PLXNA4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | novel | not found | not found | NM_020911.1 | c.1970C>T | p.Ser657Asn | 40.00% | prob. damaging |

| chr9∶95155422–95155423 | OGN | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | novel | not found | not found | NM_014057.3 | c.372_373 delAA | p. Leu124fs | 50.00% | frameshift |

| chr20∶34219872 | CPNE1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | novel | not found | not found | NM_003915.5 | c.547A>T | p.Ser183Thr | 66.67% | benign |

| chr9∶96436037 | PHF2 | 1 | 15 | 26 | rs41276200 | 0.002∶2389 | A = 120/G = 8480 | NM_005392.3 | c.2519G>A | p.Ser840Asn | N/A | benign | |

| chr3∶38307398 | SLC22A13 | 1 | 20 | 23 | rs72542450 | 0.01∶1459 | A = 84/G = 8516 | NM_004256.3 | c.47G>A | p.Arg16His | N/A | benign | |

| chrX:140785792 | SPANXE | 1,2 | 14/7 | 9/15 | novel | not found | not in database | NM_145665.1 | c.124G>T | p.Leu42Ile | N/A | not scored | |

The rare variants common to the two affected individuals were genotyped in 975 cases and 1014 controls. Penetrance with regard to the PD phenotype was assessed in 6 family members belonging to the same generation as the affected individuals. EA = European American.

Segregation Analysis and Genotyping of Additional PLXNA4 Variants

The remaining four variants shared by the two affected individuals (Table 1) were pursued further by Sanger-sequencing-based testing for segregation in 6 family members belonging to generation IV. Under the assumption that a given variant would be causal for PD, penetrance ranged between 40.0 and 66.6% in 6 individuals belonging to generation IV. Moreover, on careful scrutiny of the exome data, both index patients were found to harbor one additional, variant of PLXNA4 (p.Phe40Leu (rs145024048, 111/8489 in NHLBI-ESP exomes) for IV:11 and p.Arg302His (rs143813209, 3/8597 in NHLBI-ESP exomes) for IV:18). These two variants were also genotyped in 15 additional members of the family. PLXNA4 p.Phe40Leu was found in 5 additional individuals and p.Arg302His was found in 7 additional family members. Importantly and contrary to the exome sequencing data, by Sanger sequencing, IV:11 was also found to harbor the PLXNA4 p.Arg302His variant. The combination of the PLXNA4 index variant and p.Phe40Leu was present only in IV:11, while the index variant and PLXNA4 p.Arg302His were found in a total of 7 individuals belonging to the pedigree. None of the three additional candidate genes harbored additional non-synonymous coding variants in either IV:11 or IV:18.

Linkage Analysis

In order to further prioritize genes for follow-up, we performed parametric linkage analysis. In doing so, we identified 25 genomic regions with a suggestive linkage signal (LOD≥0.5) (Figure 1B). Only one of these regions, located on chromosome 7 (chr7∶106,254,234 to 134,663,671; maximum two-point LOD score = 0.76), contained one of the four candidate genes identified during exome sequencing, lending further support to the potential causality of variants in PLXNA4.

Mutational Screening of PLXNA4 in Case/Control Cohort

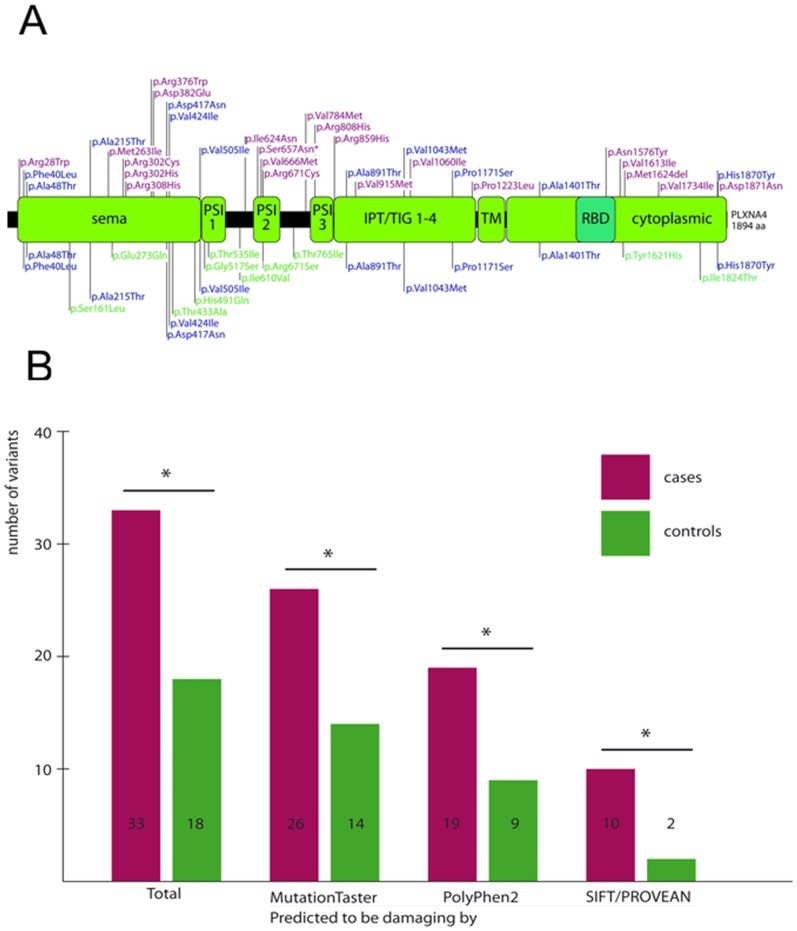

Linkage analysis highlighted the variant in PLXNA4 as a potentially causal or modifying variant for the PD phenotype in our family. Also, the affected amino acid in PLXNA4 is highly conserved in all vertebrates and two of three commonly used prediction algorithms [12]–[14] predicted it to be “damaging”. Accordingly, we screened the 32 coding exons as well as the exon/intron boundaries of PLXNA4 in 862 Austrian and German cases and 940 controls in order to assess a fuller spectrum of rare genetic variation found. For the most part, this cohort comprised the same individuals used for the above frequency assessment. In PLXNA4, a total of 38 novel (37 non-synonymous, 1 deletion) and 6 known variants (rs143813209, rs113830939, rs112682233, rs62622406, rs117458710 and rs73155258, all non-synonymous) resulting in a change in the amino acid sequence were identified (Table S2 in File S1). The large majority (86.21%) of variants were very rare, with MAF≤0.2% in controls. Overall, a similar number of cases (n = 107) and controls (n = 117) harbored at least one variant predicted to result in a changed amino acid sequence (p>0.05, χ2 test). The same held true when only variants with MAF≤1.0% (46 cases vs. 52 controls, p>0.05, χ2 test) were evaluated. Very rare variants with MAF≤0.2%, however, were more common in cases (n = 33) than controls (n = 18) (p<0.02, χ2 test). Three cases but no controls were compound heterozygous for a non-synonymous variant in PLXNA4. Variants were located throughout the entire gene (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Mutation Screening of PLXNA4 in PD case/control cohort.

(A) Location of PLXNA4 variants identified in variant screening in relation to known functional domains. An asterisk denotes the variant identified by exome sequencing. blue = variants found in both cases and controls, green = variants found only in cases, purple = variants found only in controls. (B) Analysis of PLXNA4 variants using SIFT/PROVEAN, PolyPhen2 and MutationTaster reveals an excess of rare non-synonymous variants predicted to be damaging. Insertions and deletions cannot be assessed by PolyPhen2 all and were, therefore, omitted from the analysis using this algorithm.

Of the individuals harboring a rare non-synonymous variant in PLXNA4, information regarding family history was available for 17 individuals: 3 reported a first or second degree relative with PD and a positive history of essential tremor was present in the mother and a maternal uncle in one additional individual. The only brother of the individual harboring the PLXNA4 p.Arg302Cys amino acid change was also found to have PD and to harbor this variant. However, the family was too small for formal segregation analysis.

When analyzed by means of three commonly used prediction algorithms (PolyPhen2, MutationTaster, SIFT) [12]–[14], the number of non-synonymous single nucleoide variants (SNVs) classified as functionally “damaging” (SNVs classified as “probably damaging” by PolyPhen2, “disease causing” by MutationTaster and “damaging” by SIFT) was greater in cases than in controls. This was especially prominent and statistically significant for PolyPhen2 when only very rare variants with MAF≤0.2% in controls were analyzed (PolyPhen2∶19 variants in cases vs. 9 variants in controls, p = 0.033, χ2 test; MutationTaster: 26 in cases vs. 14 in controls, p = 0.028, χ2 test; SIFT/PROVEAN: 10 in cases vs. 2 in controls, p = 0.018, Fisher’s Exact test) (Figure 2B). Deletions, which were only found in cases, cannot be assessed by PolyPhen2 and were, therefore, omitted from the analysis using this algorithm.

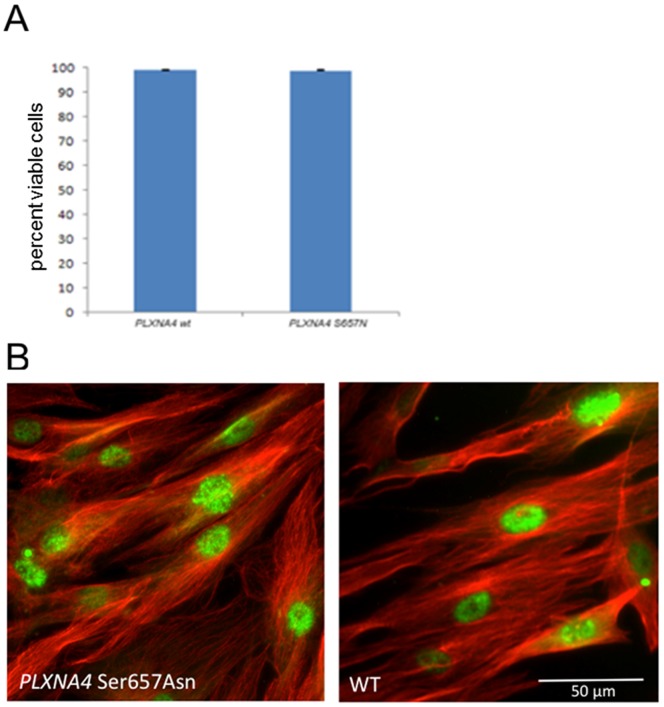

Functional Assessment of PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn in Fibroblasts

In fibroblast cell lines generated from both the index patient and an offspring who does not harbor the PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn variant (other variants not given to protect privacy) cell viability was similar (Figure 3A). Based on the results from the above mutation screening as well as the fact that PLXNA4 is known to be expressed in the brain [15] and a role for axonal guidance factors similar to PLXNA4 already postulated in PD [16], we further analyzed subcellular localization of the protein in the two cell lines but could not detect a difference (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Assessment of cell viability and subcellular protein localization in fibroblasts.

(A) The presence of PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn do not affect cell viability as assay by live-dead staining and FACS. (B) Immunohistochemistry shows similar subcellular localization of PLXNA4 (anti-PLXNA4, Sigma, 1∶500) in fibroblasts with and without the p.Ser657Asn amino acid substitution (scale bar = 50 µm).

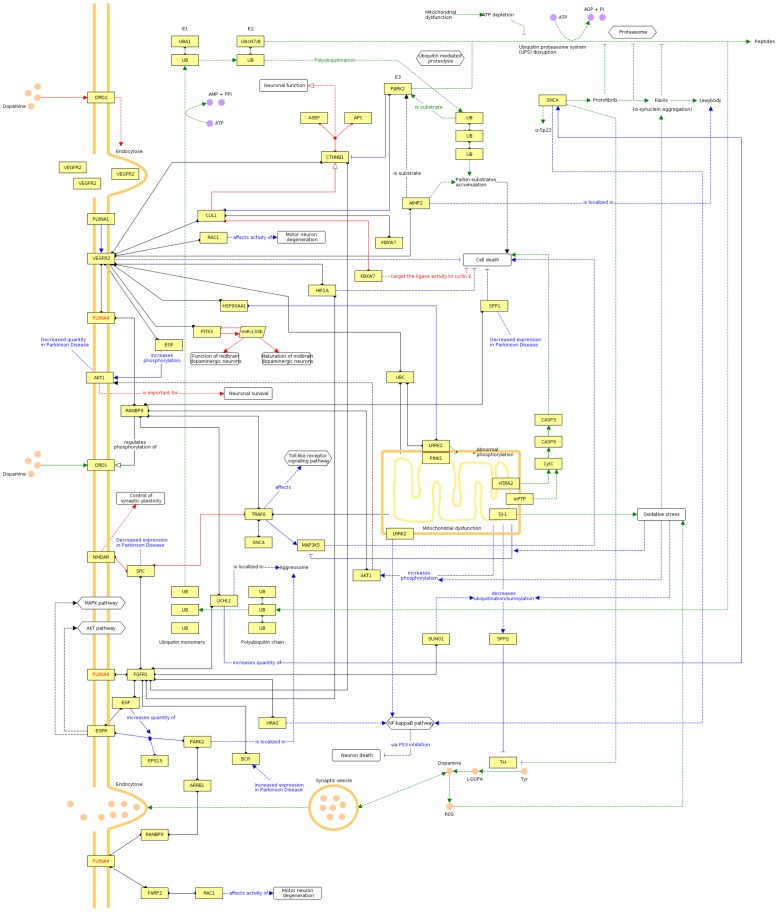

Modeling a Potential Role of PLXNA4 in the PD Network

Beyond a proposed general role of axonal guidance pathways in the development of neurodegeneration [16], [17], it is interesting to note that PLXNA4 can be place into a network containing several firmly established PD genes (SNCA, PARK2, DJ-1, LRRK2), although both known and less reliable projected interactions have to be utilized (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Qualitative multifactorial interaction network of PLXNA4 and genetic factors with known and hypothetical relevance to PD.

Edges obtained from CIDeR are highlighted in blue, PD-specific pathways from KEGG are given in green, red edges denote annotations from OMIM and edges extracted from literature, protein-protein interaction databases or high-confidence predictions are colored black. Undirected protein-protein interactions hold circular ends, directed molecular relations are marked by arcs, whereas general regulations have arrows with no filling, activations have filled arrows and inhibitions have blunted end. Dashed lines indicate indirect effects.

Discussion

In an unbiased, whole-exome approach, we identified a variant in PLXNA4 (p.Ser657Asn) as a candidate for a potentially causal variant in familial PD. Although this finding is intriguing and functionally plausible, we cannot conclude that this variant in PLXNA4 is indeed the cause of PD in our family. Also, it is interesting that both affected individuals were found to harbor two or three non-synonymous variants in PLXNA4, thus, highlighting the possibility that a “multi-hit” model within the same gene or pathway could play a role with regard to phenotype expressivity.

Three of the final four variants (PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn, OGN p.L124fs and CPNE1 p.Ser183Thr) are extremely rare and were only found in other family members but not in approximately 8,978 other individuals of European descent (genotyping sample (n = 1989), in-house exomes (n = 1739), 1000genomes (n = 1000) and NHLBI-ESP exomes (n = 4250)). This is interesting in light of the fact that–with regard to drug target genes–it was recently shown that the rarer a given variant the more likely it is functionally relevant [18]. Yet, on the other hand, this rarity also means that from a genetic standpoint, at the moment, one can neither confirm nor exclude the possibility of a causal or modifying role in the PD phenotype. Further, even taken together additional evidence highlighting PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn (suggestive linkage signal, high conservation and predicted pathogenicity, excess of very rare coding variants in cases and functional considerations) can be viewed as suggestive at best and by no means exclude the possibility of other causative or modifying genetic factors that play a role in the PD phenotype in our family.

In general, these findings highlight the fact that in many cases very large populations will be needed to conclusively judge the disease-related nature of a rare variant. Recent studies show that while the power to detect associations for genes harboring rare variants varies widely across genes, only <5% of genes achieved 80% power even assuming high odds ratios (OR) of 5 and when tested in 400 cases and 400 controls. In the same scenario, no gene out of 12,000 genes tested achieved 80% power when assuming an OR of 1.5 [19]. Statistical evaluation is further complicated by the fact that it is not unreasonable to assume that many genes will habor both variants that are protective and predisposing with regard to a given phenotype, as was recently shown for the APP locus in Alzheimer’s disease [20], which with the statistical analysis tools available today will always lead to an underestimation of the genetic contribution of rare variants at a given locus to a phenotype’s heritability [21].

Ultimately, it is also possible that the truly causal variant was not picked up in this study because it lies outside the targeted regions of the exome. Here, the use of two enrichment kits of different sizes and different exome target definitions represents a specific weakness of the study. Also, we cannot exclude that IV:18 represents a phenocopy and that the underlying cause of PD in his case is different from that of the other affected individuals in the family. If this were the case, a much larger number of candidate variants than those assessed here could contribute to bringing about the PD phenotype in the examined family.

Moreover, copy number variants, another important player in the full spectrum of genetic variation, could, at the time of study, not yet confidently be assessed in exome sequencing data and were, therefore, not evaluated in our study. Lastly, while suggestive non-significant LOD scores have been used to prioritize variants identified in exome [22] or whole genome [23] sequencing they also harbor the potential for the erroneous exclusion of true positives.

The fact that all four candidate variants were also found in unaffected family members, per se does not contradict potential causality as it is known from other autosomal dominant forms of PD that even among members of a single family, penetrance of known PD mutations can vary widely. Of individuals who harbor the LRRK2 p.Gly2019Ser mutation, for example, only 28% will develop PD by the age of 59 [24]. Thus, predicted penetrance of the variants identified in our family are in line with what is reported in the literature for other forms of autosomal dominant PD.

Plexin A4, PLXNA4, which functions as a receptor for class 3 semaphorins, holds a firmly established role in axon guidance in the development of the central and peripheral nervous systems. For example, PlxnA4 has been shown to restrict inappropriate spreading of mossy fibers within the CA3 region of the murine hippocampus [25], to direct basal dendritic arborization in layer V cortical neurons [26] and sympathetic axons [15], [27] as well as lamination and synapse formation in the outer retina [28] in the mouse.

PLXNA4 has also been implicated in neurodegenerative conditions. In the discovery stage of a large family-based GWAS assessing low-frequency (MAF≤5%) variants in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease an intronic SNP in PLXNA4 (rs277484, MAF = 2.0% in 1000genomes) yielded the most significant association signal (p = 9.0×10−10). Replication, however, is still ongoing [17]. Similarly, preliminary results have suggested decreased PLXNA4 expression in the motor cortex of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis when compared to controls, although the sample size of the study was very limited (n = 5) [29].

PLXNA4 itself has not previously been implicated in PD. Yet, a number of studies have suggested an involvement of axonal guidance pathways in PD. An early GWAS identified a SNP in semaphorin 5A (SEMA5A) as the best association signal [16] and systems biology-based follow-up studies reported an overrepresentation of axonal guidance factors in subthreshold association signals [30] which were shown to predict susceptibility to PD [31]. However, both the association signal and the pathway analysis proved difficult to replicate in other cohorts [32]–[34] which may be due to the fact that as one of the very first GWAS it was not conducted to the current quality standards. Expression studies of different brain regions, on the other hand, have repeatedly found an overrepresentation of differentially expressed axonal guidance pathways in individuals with PD when compared to controls [30], [35]–[37]. Axonal guidance pathways have also been implicated in the proper targeting of dopaminergic neurons from the murine mesencephalon to the ipsilateral striatum [38].

At the moment, both functional and genetic data addressing a role of PLXNA4 as a PD gene are inconclusive. The identification of additional larger families with PD in which PLXNA4 p.Ser657Asn or p.Arg302His segregate with the phenotype or the replication of the finding of an excess of very rare variants (MAF≤0.02%) in an independent case/control sample would lend further support to a possible role of modifying or causal variants in PLXNA4 in PD and to the interesting hypothesis of axonal guidance dysfunction in neurodegenerative conditions.

Supporting Information

Filtering scheme for variants identified by exome sequencing in the two affected family members examined.

(TIF)

Supporting Methods and Tables. Table S1 in File S1, Clinical Phenotype of Affected Individuals in PARK_0005. Table S2 in File S1, Non-Synonymous and Indel Variants Identified in Variant Screening of PLXNA4.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We are gratefully indebted to Katja Junghans, Susanne Lindhof, Jelena Golic, Sybille Frischholz und Regina Feldmann at the Insitut für Humangenetik, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Munich, Germany, for their expert technical assistance. We would also like to thank Lucas Schirmer, Neurologische Klinik und Poliklinik, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, for expert help in performing the FACS analyses.

Funding Statement

The study was funded in its majority through institutional funding from Technische Universität München and Helmholtz Zentrum München, Munich, Germany. Dr. DH received an NINDS Intramural Competitive Fellowship and research support from the Austrian Science Fund (Erwin Schroedinger Fellowship, project#J2783-B09) and the NINDS Intramural Research Program. Dr. BB and Dr. MJM received support from the Hungarian National Innovation Office (TAMOP-4-2-1/B-03/11 KMR-2010-001). Recruitment and management of the KORA cohort is funded by both institutional (Helmholtz Zentrum München, Munich, Germany) and government funding from the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (03.2007-02.2011 FKZ 01ET0713). DC was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) within the framework of the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (EXC 1010 SyNergy). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bonifati V, Fabrizio E, Vanacore N, De Mari M, Meco G (1995) Familial Parkinson’s disease: A clinical genetic analysis. Can J Neurol Sci 22: 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Payami H, Larsen K, Bernard S, Nutt J (1994) Increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in parents and siblings of patients. Ann Neurol 36: 659–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, Schaap O, Breedveld GJ, et al. (2003) Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science 299: 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, et al. (1998) Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392: 605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, et al. (2004) Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 44: 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, et al. (1997) Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 276: 2045–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MM, Harvey K, et al. (2004) Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 304: 1158–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, et al. (2004) Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron 44: 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vilariño-Güell C, Wider C, Ross OA, Dachsel JC, Kachergus JM, et al. (2011) VPS35 Mutations in Parkinson Disease. Am J Hum Genet 89: 162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zimprich A, Benet-Pagès A, Struhal W, Graf E, Eck SH, et al. (2011) A Mutation in VPS35, Encoding a Subunit of the Retromer Complex, Causes Late-Onset Parkinson Disease. Am J Hum Genet 89: 168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schulte EC, Mollenhauer B, Zimprich A, Bereznai B, Lichtner P, et al. (2012) Variants in eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G1 in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurogenetics 13: 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D (2010) MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods 7: 575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S (2002) Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acid Res 30: 3894–3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, et al. (2010) A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 7: 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suto F, Ito K, Uemura M, Shimizu M, Shinkawa Y, et al. (2005) Plexin-A4 Mediates Axon-Repulsive Activities of Both Secreted and Transmembrane Semaphorins and Plays Roles in Nerve Fiber Guidance. J Neurosci 25: 3628–3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maraganore DM, de Andrade M, Lesnick TG, Strain KJ, Farrer MJ, et al. (2005) High-Resolution Whole-Genome Association Study of Parkinson Disease. Am J Hum Genet 77: 685–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung G, Buros J, Lunetta KL, Foroud TM, Mayeux R, et al.. (2011) Identification of Rare Variants for Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease in a Family-Based Genome-Wide Association Study. Abstract No. 221. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics 2011, Montreal, Canada.

- 18. Nelson MR, Wegmann D, Ehm MG, Kessner D, St Jean P, et al. (2012) An abundance of rare functional variants in 202 drug target genes sequenced in 14,002 people. Science 337: 100–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O’Connor TD, Fu W, Kenny EE, et al. (2012) Evolution and Functional Impact of Rare Coding Variation from Deep Sequencing of Human Exomes. Science 337: 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, et al. (2012) A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 488: 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu DJ, Leal SM (2012) Estimating Genetic Effects and Quantifying Missing Heritability Explained by Identified Rare-Variant Associations. Am J Hum Genet 91: 585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson JO, Mandrioli J, Benatar M, Abramzon Y, Van Deerlin VM, et al. (2010) Exome sequencing reveals VCP mutations as a cause of familial ALS. Neuron 68: 857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sobreira NL, Cirulli ET, Avramopoulos D, Wohler E, Oswald GL, et al. (2010) Whole-genome sequencing of a single proband together with linkage analysis identifies a Mendelian disease gene. PLoS Genet 6: e1000991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Healy DG, Falchi M, O’Sullivan SS, Bonifati V, Durr A, et al. (2008) Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 7: 583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suto F, Tsuboi M, Kamiya H, Mizuno H, Kiyama Y, et al. (2007) Interactions between Plexin-A2, Plexin-A4, and Semaphorin 6A Control Lamina-Restricted Projection of Hippocampal Mossy Fibers. Neuron 53: 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tran TS, Rubio ME, Clem RL, Johnson D, Case L, et al. (2009) Secreted semaphorins control spine distribution and morphogenesis in the postnatal CNS. Nature 462: 1065–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Waimey KE, Huang PH, Chen M, Cheng HJ (2008) Plexin-A3 and Plexin-A4 Restrict the Migration of Sympathetic Neurons but not Their Neural Crest Precursors. Dev Biol 315: 448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsuoka RL, Jiang Z, Samuels IS, Nguyen-Ba-Charvet KT, Sun LO, et al. (2012) Guidance-cue control of horizontal cell morphology, lamination, and synapse formation in the mammalian outer retina. J Neurosci 32: 6859–6868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Körner S, Wilzek N, Thau S, Knippenberg S, Dengler R, et al.. (2012) mRNA Expression von Axon-Leitproteinen (Axon guidance proteins) in humanem post-mortem Motorkortex bei Amyothropher Lateralsklerose. Abstract V24. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the German Society for Neurology 2012, Hamburg, Germany.

- 30. Edwards YJ, Beecham GW, Scott WK, Khuri S, Bademci G, et al. (2011) Identifying Consensus Disease Pathways in Parkinson’s Disease Using an Integrative Systems Biology Approach. PLoS one 6: e16917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lesnick TG, Papapetropoulos S, Mash DC, Ffrench-Mullen J, Shehadeh L, et al. (2007) A Genomic Pathway Approach to a Complex Disease: Axon Guidance and Parkinson Disease. PLoS Genet 3: e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bialecka M, Kurzawski M, Klodowska-Duda G, Opala G, Tan EK, et al. (2006) Polymorphism in semaphoring 5A (Sema5A) gene is not a marker of Parkinson’s disease risk. Neurosci Lett 399: 121–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clarimon J, Scholz S, Fung HC, Hardy J, Eerola J, et al. (2006) Conflicting results regarding the semaphorin gene (SEMA5A) and the risk for Parkinson disease. Am J Hum Genet 78: 1082–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Y, Rowland C, Xiromerisiou G, Lagier RJ, Schrodi SJ, et al. (2008) Neither replication nor simulation supports a role for the axon guidance pathway in the genetics of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 3: e2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bossers K, Heerhoff G, Balesar R, van Dongen JW, Kruse CG, et al. (2009) Analysis of gene expression in Parkinson’s disease: Possible involvement of neurotrophic support and axon guidance in dopaminergic cell death. Brain Pathol 19: 91–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sutherland GT, Matigian NA, Chalk AM, Anderson MJ, Silburn PA, et al. (2009) A cross-study transcriptional analysis of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS one 4: e4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang K, Li M, Bucan M (2007) Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet 81: 1278–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kawano H, Horie M, Honma S, Kawamura K, Takeuchi K, et al. (2003) Aberrant trajectory of ascending dopaminergic pathway in mice lacking Nkx2.1. Exp Neurol 182: 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA. Available: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/. Accessed October 23, 2012.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Filtering scheme for variants identified by exome sequencing in the two affected family members examined.

(TIF)

Supporting Methods and Tables. Table S1 in File S1, Clinical Phenotype of Affected Individuals in PARK_0005. Table S2 in File S1, Non-Synonymous and Indel Variants Identified in Variant Screening of PLXNA4.

(DOC)