Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about factors that influence patients’ preferences for the return of incidental findings from genome sequencing. This study identified attributes of incidental findings that were important to patients and developed a discrete choice experiment (DCE) instrument to quantify patient preferences.

Methods

An initial set of key attributes and attribute levels was developed from a literature review and in consultation with experts. The attributes’ salience and communication were refined using focus group methodology (N=12) and cognitive interviews (N=6) with patients who had received conventional genetic testing for familial colorectal cancer or polyposis syndromes. The attributes and levels used in the hypothetical choices presented to participants were identified using validated experimental design techniques.

Results

The final DCE instrument incorporates the following attributes and levels: lifetime risk of disease (5%, 40%, 70%); disease treatability (medical, lifestyle, none); disease severity (mild, moderate, severe); carrier status (yes, no); drug response likelihood (high, moderate, none), and test cost ($250, $425, $1000, $1900).

Conclusion

Patient preferences for incidental genomic findings are likely influenced by a complex set of diverse attributes. Quantification of patient preferences can inform patient-provider communication by highlighting the attributes of incidental findings that matter most to patients and warrant further discussion.

INTRODUCTION

Next-generation genomic sequencing offers significant clinical promise, and the rapidly decreasing cost of these technologies implies that whole exome and whole genome sequencing may soon replace conventional genetic testing in the clinical setting. In contrast with current methods, these comprehensive sequencing approaches are likely to generate large numbers of incidental findings 1. These findings will be of varying clinical significance: some may be well studied and medically actionable, while others may not be validated or clinically relevant2.

Previous research on the benefit to the ‘end-user’ of genetic information – the patient – focused on the clinical utility of incidental findings3,4, with clinical utility defined as the potential for a given finding to improve clinical or health status outcomes. Researchers in the social sciences, however, have long acknowledged that patients also value information that does not inform clinical management5–7. In genetics, the ‘value of knowing’ has become an aspect of the conversation surrounding the utility of genomic technology. For example, Facio et al. reported that a third of participants receiving genomic sequencing as part of the ClinSeq study expressed a preference to receive genomic results on the grounds that all knowledge is positive8. Another study found that lay participants felt that they – not experts – were best able to judge the utility of potential genetic information9.

Although several studies have measured preferences for genetic testing 10–16, to our knowledge, no studies have been designed or conducted to quantify patient preferences for incidental findings from genomic sequencing. Such studies are needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the personal utility of genome sequencing and to inform practice guidelines and other policies related to the return of results from genomic testing. Further, individuals’ preferences surrounding the return of incidental findings can inform the development of educational materials and decision support tools to guide patients and providers through the process of returning these findings.

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are tools for quantifying patient preferences for a good or service17–20. DCEs fall under the umbrella term of conjoint analysis, which include a range of methods (ranking, rating, or choice-based approaches) that quantify preferences for various attributes of a health care good. DCEs are popular in health economics because of their underlying behavioral framework for modeling choice behavior. In a DCE, participants are asked to choose from a set of two or more options that describe a particular good or service using a limited set of characteristics (called attributes). Participants repeat this hypothetical choice multiple times, and for each choice the specific values (called levels) of the characteristics are varied in a pre-determined fashion. For each choice, participants must make tradeoffs as to the relative importance of each attribute and its level. These choices are modeled using limited dependent regression analysis to determine which attributes drive patient preferences and quantify the marginal and aggregate value patients place on the good or service. DCEs are therefore particularly well suited to measuring the value of multidimensional technologies like genomic sequencing.

Construction of a DCE instrument begins by determining the attributes that are jointly most relevant to the research question and salient to the patient population. Next, plausible and relevant levels are chosen for each attribute. DCEs typically include three to seven attributes and three to four levels for each attribute21. Hypothetical scenarios to describe the technology are constructed using all possible combinations of the attributes and levels. Because the number of hypothetical scenarios is often quite large, validated experimental design techniques that ensure unbiased and statistically efficient parameter estimates are used to reduce the number of specific choices presented to respondents to a manageable number, typically eight to sixteen18.

The aim of this study was to identify the attributes and levels of incidental genomic findings in the context of genetic testing for colon cancer susceptibility that are most important to, and cognitively understood by, patients, and to develop a DCE instrument that will enable the quantification of patients’ personal utility for incidental findings from next-generation genomic sequencing technologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of the DCE instrument (Instrument to Measure PReferences for Information from Next-generation Testing (IMPRINT)) was conducted as part of a randomized controlled trial of whole exome sequencing (WXS) compared to usual care for patients being evaluated for a possible inherited colorectal cancer or polyposis syndrome (the NEXT [New EXome Technology in] Medicine Study). The trial has several aims related to WXS within a clinical setting, including developing a framework for returning the incidental findings in a clinical setting, and measuring the clinical, patient, and economic outcomes of using WXS in lieu of usual care genetic testing. The trial began enrollment in September 2012 and will accrue approximately 220 patients over the next three years. The activities described in this paper were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Washington and British Columbia Cancer Agency.

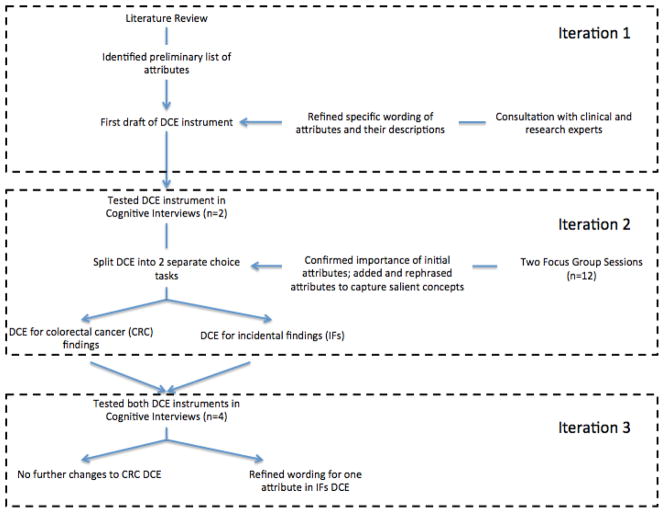

As the DCE instrument was developed for use in a clinical trial setting, the development process was completed within a short timeline and followed a multifaceted and iterative process (Figure 1). The initial list of possible attributes and attribute levels was chosen based on literature review, the aim of the study, and in consultation with experts. In the second iteration, we supplemented and refined the attributes and levels with input from two focus group sessions and two cognitive interviews. Lastly, we modified the instrument and refined attribute wording and descriptions based on four additional cognitive interviews.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of development process.

Literature review and consultation with experts

We sought to capitalize on the recent growth in studies evaluating patient preferences for genomic information10–16. A literature review for English-language studies was conducted to identify previous DCEs examining the use of genomic technologies in a clinical setting. We searched Medline for the following terms: (‘genetic testing’ or ‘genomic’) and (‘conjoint analysis’ or ‘discrete choice experiment’). Articles were evaluated for potential attributes if they examined the degree to which factors affected patients’ preferences for genomic or genetic testing. The initial list of attributes was drafted by several members of our team (DLV, DAR, and CSB) and then discussed with experts in medical and research genetics (FMH, GPJ, and WB) regarding salience and how best to communicate the complicated concepts as meaningful and comprehensive attributes.

Focus groups

We conducted two focus groups in May 2012 with patients who underwent a clinical workup for familial colorectal cancer/polyposis syndromes at the University of Washington Genetic Medicine Clinic within the past 24 months (see Table 1 for demographic information). We searched for people who came in for the genetic workup based on a suspected familial inherited cancer syndrome; patients included those with their own cancer diagnosis as well as some who had a strong family history but no clinical diagnosis of cancer. Focus groups are a useful technique for gathering information from laypeople about complex topics, and observing the dynamics among participants can offer insights into the kinds of information that influence individuals’ attitudes about the topic under study22,23. In an attempt to capture a range of genetic testing experiences, we followed a purposeful sampling strategy24: one discussion (N=8) was with patients whose genetic testing was non-informative and one (N=4) included patients who had received a definitive genetic result. Recruitment response rates were 19% and 14%, respectively.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| Focus Group 1 (Non-informative result) N=8 |

Focus Group 2 (Definitive finding) N=4 |

Cognitive interviews N=6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean (range)] | 54 (30 – 64) | 61 (50 – 67) | 55 (25–71) |

| Sex [n] | |||

| Male | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Female | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Race [n] | |||

| Black / African American | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| White | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Educational attainment | |||

| High school | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| College degree | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Graduate degree | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Annual income | |||

| 0–$25,000 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| $50,000–$75,000 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| >$75,000 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Declined | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Two experienced qualitative researchers (SBT and SMF) led the focus group discussions using a semi-structured guide to explore participants’ experiences, beliefs, and attitudes about genetic testing and WXS. Each session lasted 2 hours. The discussions were audio recorded and transcribed. Following team review of the field notes and transcripts, we determined that additional sessions were not required, as our aim was not to conduct a summative study, but rather to gather formative data that could be combined with results from the literature review, expert input, and cognitive interviews to inform development of the DCE. We performed a close reading of the focus group transcripts with the goals of identifying features of the testing experience that mattered to patients, seeking any attributes that were salient to patients but not identified in the existing literature, and gaining insight into the language patients used to describe attributes.

Cognitive interviews

We conducted cognitive interviews (N=6) between March and May 2012 with participants who met the eligibility criteria described above (Table 1 for demographic information). Cognitive interviews offer the opportunity to identify items that respondents do not understand or cannot answer, where they “get stuck,” and how long it takes members of the target audience to complete the questionnaire25. To ensure consistency, a single member of the research team (CSB) conducted the interviews and another member of the team (DLV) observed and took detailed notes. Sessions were audiorecorded, but not transcribed. In all cognitive interviews, we asked respondents to complete the choice tasks and explain their understanding of each attribute, as well as the particular tradeoffs they considered when making their choice. The interview guide included both “think-aloud” and “probing” techniques; we also asked respondents to describe any additional attributes they judged important when considering genetic testing.

Construction of the DCE

The DCE questionnaire was developed from an initial set of attributes and levels identified from the literature review and expert opinion (first iteration) as well as focus groups and cognitive interviews (second and third iterations). All iterations included 16 choice tasks; each task asked participants to choose between two alternative genetic tests described by the chosen attributes, or select an “opt-out” option to accommodate those who may not wish to receive any information from genetic testing26.

RESULTS

Iteration 1: Creating the initial list of attributes

We identified seven DCEs that examined individual preferences for different aspects of genetic testing in our literature review10–16. The factors broadly related to the domains of testing effectiveness, risk of disease, the type of results returned to the patient or family member, potential consequences to the patient’s family, convenience of the testing procedure, recommendation of the doctor to undergo genetic testing, time waiting for results of the test, and cost of the test.

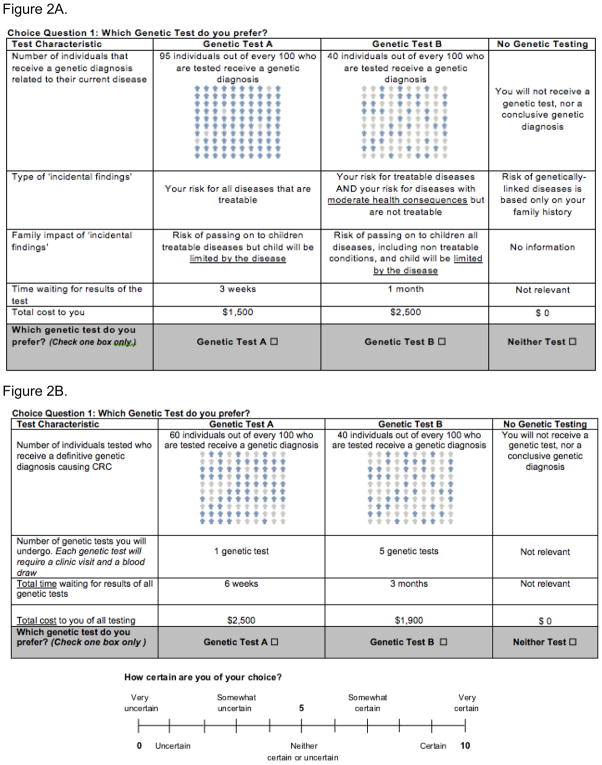

These factors informed the initial list of attributes for the DCE, which was revised through expert consultation. We included attributes for the likelihood that patients received a genetic diagnosis for their colon cancer as well as the time waiting for genetic results. These attributes were chosen because a hypothesis of the NEXT Medicine Study is that WXS will yield a greater number of genetic diagnoses in a shorter time frame than usual care, and we wanted to evaluate how patients valued these attributes. After consultation with several genetics healthcare providers and researchers, we stratified the type of ‘extra’ information received from genomic testing into two attributes: one that addressed treatability and severity of the newly identified disease and another that described the specific health consequences for family members. Lastly, we included an attribute for the total cost of the test so that we could calculate a willingness-to-pay metric for each of the attributes, which can be used to inform cost-benefit analysis.28 Table 2 shows the list of attributes and levels included in our initial DCE; an example choice task is shown in Figure 2A and the patient education section of the DCE instrument, which includes descriptions of each attribute and attribute level, is included in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Table 2.

List of all attributes and attributes levels of the initial and final iteration of DCE.

| Initial iteration | |

|---|---|

| Attribute | Levels |

| Number of individuals that receive a genetic diagnosis related to their current disease |

|

| Type of ‘incidental findings’ |

|

| Family Impact of ‘incidental findings’ |

|

| Time waiting for results of the test |

|

| Total cost to you |

|

| Final iteration (DCE for incidental findings) | |

| Attribute | Levels |

| You receive information on diseases that have the following lifetime risk or higher. |

|

| Treatability of the newly identified disease(s) |

|

| Health consequences of the newly identified disease(s) |

|

| Carrier status for a gene not affecting you, but that may affect family members health |

|

| Information on your likely response to medications you may or may not be currently taking |

|

| Cost to you not covered by insurance |

|

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Example of choice task from initial draft of discrete choice experiment.

Figure 2B. Example of choice task from final draft of discrete choice experiment for colorectal cancer results.

Iteration 2: Findings from the focus groups and cognitive interviews

We solicited information about novel themes primarily from the focus groups, and information about readability and usability primarily from the cognitive interviews; however, due to the tight timeline under which the DCE was developed, these efforts overlapped and the qualitative findings are therefore presented thematically rather than chronologically.

The cognitive interview and focus group participants exhibited a range of qualitative preferences for information from genomic testing. Some participants expressed a desire to know all genomic information (“I’d want to know everything. I’d want no sugar coating at all”), while others preferred to receive findings dependent on certain factors (“I think if I could be treated I would want to know, but if it’s something that they may not be able to treat or if it’s something that they can’t guarantee that I’m going to get or the percentage is like 50/50 then I have to just live wondering about this”), and still others expressed a general apprehension about receiving genomic information (“I just think you could go nuts treating all these little possibilities. I mean it just seems like there would be no end to, I don’t know, trying to research what you should be eating or not eating for this condition. I would go crazy”). Despite the wide range of qualitative preferences for incidental findings, several specific attributes of the test or its results emerged as important for patients considering genomic testing, specifically treatability and severity, family impact, and lifetime risk of the incidentally identified disease.

The participants confirmed that both treatability and severity of the incidental findings were important, but indicated that they regarded these as distinct concepts. Whereas some participants wanted to know about incidental findings that were treatable (“Because particularly in those areas where if lifestyle changes or treatment are available, then even with a small risk, I’d want to know because I’d want to implement those lifestyle changes and consider the treatments available”), others wanted information that would have important health consequences (“Essentially how it’s going to affect my independence and how much pain I’m going to have”).

Participants also confirmed that family impact was important, but that they considered it to be an inherent and inevitable aspect of genetic testing. For some participants, the possible implications for family members were a strong reason to pursue testing in the first place (“I felt like I needed to know [my genetic results] as a parent, but I also felt like I needed to know for my children”). Carrier status testing emerged as an important and distinct type of genomic information, although again participants exhibited a range of qualitative preferences for such information. One focus group participant thought he would use the information to make reproductive decisions (“If we knew that there was a likelihood that there would be a bad [reproductive] outcome, then that would maybe prompt me to push more towards like ‘Okay, we should research other options for having children’”), whereas another worried that such information would burden and complicate such decisions (“I think the really hard part would be getting it before you conceive and feeling an obligation to take it into account when deciding whether or not to have children”).

The lifetime risk of developing the incidentally identified disease emerged as a salient concept in both focus groups and cognitive interviews. Some participants stated that they simply wanted to know the information (“I want to know if it’s 10% or 90%. I think that’s important information”) whereas others stated that this risk would be an important factor in determining what incidental findings they would want to receive (“I think I’d probably only want to know if [the risk] was over 50%”).

The two cognitive interviews using the first draft of the DCE questionnaire indicated that participants found the initial DCE instrument difficult to understand. Specifically, the respondents struggled to distinguish the attributes related to familial colorectal cancer/polyposis syndromes and WXS when presented together in one choice task. For example, one respondent expressed confusion at the initial combination of attributes: “I guess I am a little confused then. Because this test is much more inclusive [for incidental findings], why is it going to have much less positive results [for colorectal cancer]?” The second participant stated that she preferred to evaluate attributes relevant to her cancer diagnosis independently of the incidental findings: “I think it would actually be good to have a [colorectal cancer]-specific one, and okay, here’s all the other stuff. I think that would be helpful.”

Conclusions from Iteration 2 and changes to the DCE

We made several changes to the draft DCE instrument based on feedback from the focus groups and initial cognitive interviews (Figure 2A). The most significant change was to split the DCE instrument into separate instruments for colorectal cancer genetic results and incidental findings. The development of the DCE for colorectal cancer results is similar to previous DCEs that have been developed for genetic testing and was complete by the end of iteration 210. It included attributes for (1) chance the test will find a gene that caused your cancer, (2) number of genetic tests, (3) time waiting for the results, and (4) total cost (Figure 2B). We did not include an attribute to reflect the doctor’s recommendation regarding genetic testing as all participants in the NEXT Medicine Trial are referred for genetic testing. The development of a DCE for the return of incidental findings from genomic testing was more complex and required several additional changes to incorporate the findings from our qualitative work.

First, we reiterated the general family impact of genetic testing in the background section (see Supplementary Materials and Methods for the patient education section of both the initial and final DCEs) and rephrased the attribute to be specific to carrier testing. Second, we split treatability and severity of disease into separate attributes. Third, we added lifetime risk of developing the incidentally identified disease as an attribute. Lastly, we added an attribute to describe sequencing results that could provide information on participants’ likely response to medications, in part because this attribute emerged in our initial literature reviews and in our qualitative work, and also because a decision was made to offer such information to participants in the NEXT Medicine Study (based on expert recommendation).

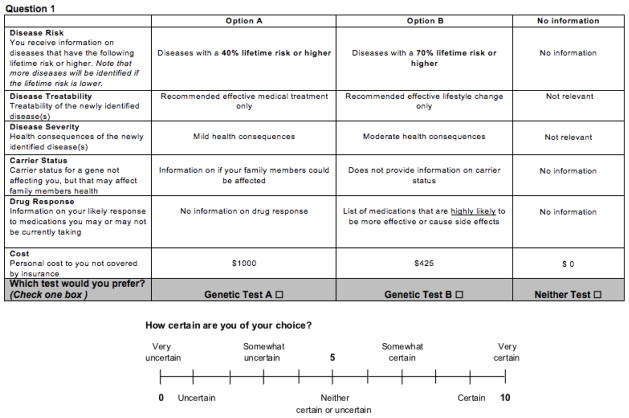

Iteration 3: Confirming relevance and understanding by the target population

With the exception of lifetime risk of disease, participants in the four additional cognitive interviews interpreted the attributes similarly, and in the manner intended by our research team. Several respondents understood the “lifetime risk of disease” attribute as a measure of test accuracy, taking higher values (i.e., tests that returned only incidental findings with a relatively high probability of developing the disease) as representing a “better” test. For example, one respondent interpreted an 80% lifetime risk as: “80% of the time they’re going to show me other possibilities with this test”. To clarify the construct, we rephrased the attribute from “Your identified risk of developing a disease you currently do not have” to the text shown in the example choice task (Figure 3). The revised instrument presents lifetime risk as a threshold, below which one would not receive results of incidentally identified diseases, and emphasizes that lower thresholds would provide more results.

Figure 3.

Example of choice task from final draft of discrete choice experiment for incidental findings.

Our final DCE therefore included the following attributes: disease risk, disease treatability, disease severity, carrier status, drug response, and total cost (see Table 2 for attribute levels and the Appendix for descriptions of each attribute and level). In addition, respondents’ certainty of choice was included after each question to examine how the complexity of each choice task affects the statistical efficiency of the parameter estimates. An example choice task from the final DCE is shown in Figure 3. Individuals completed the instrument within approximately 10–30 minutes and the Flesch-Kincaid grade level of the final instrument was 7.0, indicating that an average seventh grader should understand the text.

DISCUSSION

Despite a wide range of qualitative preferences for incidental findings, we identified six key attributes that encapsulate the most salient patient preferences relevant to our study aims: lifetime risk, treatability, severity, carrier status, drug response, and total cost. We also found that patients who stated a preference for receiving genomic information often wanted to know the results even in the absence of clinical utility.

Implications

The existence of heterogeneous preferences10,29, particularly across multiple dimensions, highlights the need for practical approaches to elicit these preferences in clinical practice to facilitate shared decision-making. Some researchers have suggested binning incidental findings into categories based on their clinical utility and validity30. A recent study evaluated attitudes toward genomic information based on treatability and found that intentions to receive information were only mildly influenced by the treatability of the findings8. In our focus groups, some participants wished to know any type of genomic information if the risk of developing the disease was sufficiently high, while others wished to know if the incidentally identified disease was life threatening and treatable, regardless of the lifetime risk. These findings suggest that approaches to classifying incidental findings based on a single dimension, such as treatability or clinical utility, may not adequately reflect the totality and nuance of patient preferences for information on incidental findings.

Comparison to similar studies

Previous studies have assessed patient attitudes and qualitative preferences for return of genomic findings in both research and clinical settings8,9,31–35. While there is a wide body of literature concerning the ethical issues surrounding return of individual findings from research studies and the preferences of individuals to know this information31–35, the preferences of patients for the return of genomic results in the context of clinical care are less well studied.

Two recent studies assessed preferences for the return of results in a clinical setting8,9. Townsend et al. solicited attitudes and qualitative preferences toward receiving incidental findings from health-care providers, the general public, and parents whose children received genetic testing9. Lay participants felt strongly about their right to choose the types of incidental findings they received. Participants with a preference for knowing some, but not all, incidental findings favored the idea of categories based on clinical relevance, but felt that relevance was a subjective concept that should not be determined by their physician. Our work expands on these findings by identifying the categories patients might use to classify what incidental findings they wished to receive.

Facio et al. assessed preferences and attitudes toward learning results from whole genomic sequencing in a sample of participants from ClinSeq, a research study focused on individuals at familial risk of cardiovascular disease8. Nearly all participants expressed a desire to know genomic information. In contrast, several participants in our study expressed strong apprehension about receiving incidental findings. These differences are likely explained by the different patient samples. The ClinSeq study had the explicit goal of sequencing genomes and returning information from that analysis36; thus patients were likely to have a stronger than average desire to know genomic information.

Similarly to Facio, we found that among those who did express an interest in knowing genomic information, a primary reason was a confidence in their ability to use the information to prevent future disease, even in the absence of clear medical utility. A challenge going forward therefore will be for health care providers to manage these expectations and help patients interpret and understand the inevitable findings of uncertain significance.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, we conducted a limited number of interviews and focus groups, all of which were with patients who received genetic testing for colorectal cancer or polyposis. We acknowledge that not all possible attributes were likely captured by our multifaceted approach to generate attributes; however, our intended goal was not complete saturation of relevant concepts or attributes, but rather a preliminary (and pragmatic) assessment of the most important attributes that drive patient preferences in order to build a DCE instrument. We hope that future work builds on ours, and in particular evaluates how the relevance of these and/or other attributes varies in other racial or ethnic populations. As all participants in our interviews and focus groups had received genetic counseling and genetic testing, they may represent a group of patients who are more interested in the type of information that could be obtained from genomic sequencing and may have better knowledge than the general public on issues surrounding genetic testing. However, in the study by Townsend et al. the participants from the public and parents of children who had received genetic testing exhibited very similar qualitative preferences towards genomic sequencing and incidental findings9. Moreover, in our sample, we did observe a wide range of preferences and attitudes towards incidental findings, with some participants wishing to know “everything” and others exhibiting strong reservations about learning incidental genomic information.

Second, we acknowledge that the brief descriptions of attributes and levels will likely not fully capture the breadth and complexity of attitudes underlying the expression of individual preferences. Again, our findings suggest that a more comprehensive exploration of attitudes is warranted. However, our qualitative work was sufficient for the purposes of reducing the key concepts relevant to genomic testing into a set of attributes that could be used in a stated preference DCE that was not cognitively burdensome to respondents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study describes the development of a DCE instrument to measure patient preferences for information from next generation genomic sequencing and to quantify patients’ personal utility. We found that patients exhibited a wide range of attitudes towards genomic testing and the return of incidental findings. Despite these heterogeneous qualitative preferences, we were able to identify several key attributes that were consistently associated with patient preferences and views on genomic testing. This allowed us to develop a DCE tool for future studies. The results of the DCE could be used to inform patient-provider dialogue, perhaps by prompting discussions about particular attributes that may otherwise have been ignored. The results could also be used to design educational materials for patients to improve patient-provider communication and shared decision-making. Implementation of a DCE for use in clinical practice may be challenging because of time constraints and complexity, but such approaches warrant further study. Lastly, our findings highlight the need for further research on patient preferences in genomic sequencing, and for effective ways of helping patients and providers understand and address these preferences in the return of incidental findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgement: This study was supported by grant number U01 HG0006507-01 from the National Human Genome Research Institute, and by the University of Washington Northwest Institute of Genetic Medicine awarded from the Washington State Life Sciences Discovery Funds (LDSF; grant 265508).

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at the Genetics in Medicine website.

References

- 1.Ashley EA, Butte AJ, Wheeler MT, et al. Clinical assessment incorporating a personal genome. Lancet. 2010 May 1;375(9725):1525–1535. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60452-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knoppers BM, Joly Y, Simard J, Durocher F. The emergence of an ethical duty to disclose genetic research results: international perspectives. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006 Nov;14(11):1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosse SD, Khoury MJ. What is the clinical utility of genetic testing? Genet Med. 2006 Jul;8(7):448–450. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000227935.26763.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargent D. Genomic classifiers in colon cancer - clinical utility. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008 Jul;2(4 Suppl):S35–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berwick DM, Weinstein MC. What do patients value? Willingness to pay for ultrasound in normal pregnancy. Med Care. 1985 Jul;23(7):881–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster MW, Mulvihill JJ, Sharp RR. Evaluating the utility of personal genomic information. Genet Med. 2009 Aug;11(8):570–574. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a2743e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosse SD, Kalman L, Khoury MJ. Evaluation of the validity and utility of genetic testing for rare diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:115–131. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facio FM, Eidem H, Fisher T, et al. Intentions to receive individual results from whole-genome sequencing among participants in the ClinSeq study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012 Aug 15; doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend A, Adam S, Birch PH, Lohn Z, Rousseau F, Friedman JM. I want to know what’s in Pandora’s box : Comparing stakeholder perspectives on incidental findings in clinical whole genomic sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2012 Oct;158A(10):2519–2525. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regier DA, Friedman JM, Makela N, Ryan M, Marra CA. Valuing the benefit of diagnostic testing for genetic causes of idiopathic developmental disability: willingness to pay from families of affected children. Clin Genet. 2009 Jun;75(6):514–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall J, Fiebig DG, King MT, Hossain I, Louviere JJ. What influences participation in genetic carrier testing? Results from a discrete choice experiment. J Health Econ. 2006 May;25(3):520–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan M, Diack J, Watson V, Smith N. Rapid prenatal diagnostic testing for Down syndrome only or longer wait for full karyotype: the views of pregnant women. Prenat Diagn. 2005 Dec;25(13):1206–1211. doi: 10.1002/pd.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop AJ, Marteau TM, Armstrong D, et al. Women and health care professionals’ preferences for Down’s Syndrome screening tests: a conjoint analysis study. BJOG. 2004 Aug;111(8):775–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis SM, Cullinane FN, Bishop AJ, Chitty LS, Marteau TM, Halliday JL. A comparison of Australian and UK obstetricians’ and midwives’ preferences for screening tests for Down syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2006 Jan;26(1):60–66. doi: 10.1002/pd.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbild L, Bech M, Gyrd-Hansen D. Estimating the Danish populations’ preferences for pharmacogenetic testing using a discrete choice experiment. The case of treating depression. Value Health. 2009 Jun;12(4):560–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne K, Fargher EA, Roberts SA, et al. Valuing pharmacogenetic testing services: a comparison of patients’ and health care professionals’ preferences. Value Health. 2011 Jan;14(1):121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridges JF, Kinter ET, Kidane L, Heinzen RR, McCormick C. Things are Looking up Since We Started Listening to Patients: Trends in the Application of Conjoint Analysis in Health 1982–2007. Patient. 2008 Dec 1;1(4):273–282. doi: 10.2165/01312067-200801040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health--a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011 Jun;14(4):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ. 2000 Jun 3;320(7248):1530–1533. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. In: Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Bateman I, editor. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall D, Bridges JF, Hauber B, et al. Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health - How are Studies being Designed and Reported?: An Update on Current Practice in the Published Literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient. 2010 Dec 1;3(4):249–256. doi: 10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995 Jul 29;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan DL. The Focus Group Guidebook. Thousand Oaks; Sage Publications: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton Michael Quinn. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan M, Skatun D. Modelling non-demanders in choice experiments. Health Econ. 2004 Apr;13(4):397–402. doi: 10.1002/hec.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Street DJ, Burgess L, Louviere J. Quick and easy choice sets: constructing optimal and nearly optimal stated choice experiments. Journal of International Marketing and Marketing Research. 2005;22:459–470. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regier DA, Friedman JM, Marra CA. Value for money? Array genomic hybridization for diagnostic testing for genetic causes of intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2010 May 14;86(5):765–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regier DA, Ryan M, Phimister E, Marra CA. Bayesian and classical estimation of mixed logit: An application to genetic testing. J Health Econ. 2009 May;28(3):598–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg JS, Khoury MJ, Evans JP. Deploying whole genome sequencing in clinical practice and public health: meeting the challenge one bin at a time. Genet Med. 2011 Jun;13(6):499–504. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318220aaba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Daniel J, Haga SB. Public perspectives on returning genetics and genomics research results. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14(6):346–355. doi: 10.1159/000324933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bollinger JM, Scott J, Dvoskin R, Kaufman D. Public preferences regarding the return of individual genetic research results: findings from a qualitative focus group study. Genet Med. 2012 Apr;14(4):451–457. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ries NM, LeGrandeur J, Caulfield T. Handling ethical, legal and social issues in birth cohort studies involving genetic research: responses from studies in six countries. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards KL, Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, et al. Genetics researchers’ and IRB professionals’ attitudes toward genetic research review: a comparative analysis. Genet Med. 2012 Feb;14(2):236–242. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dressler LG, Smolek S, Ponsaran R, et al. IRB perspectives on the return of individual results from genomic research. Genet Med. 2012 Feb;14(2):215–222. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biesecker LG, Mullikin JC, Facio FM, et al. The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res. 2009 Sep;19(9):1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.