Introduction

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) catalyze the conversion of nucleotides (NDPs or NTPs where N = C, U, G, or A) to 2′-deoxynucleotides (dNDPs or dNTPs)1 and are responsible for controlling the relative ratios and absolute concentrations of cellular dNTP pools. For this reason, RNRs play a major role in ensuring the fidelity of DNA replication and repair. RNRs are found in all organisms and are classified based on the metallocofactor used to initiate catalysis,1 with the class Ia RNRs requiring a diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y•) cofactor.

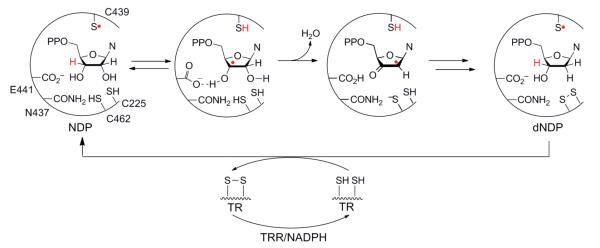

The prototypical class Ia RNR from E. coli, the subject of this account, is composed of two subunits, α2 and β2, and is active as an α2β2 complex, as highlighted in Figure 1. α2 houses the catalytic site for substrate (S) reduction and two allosteric effector (E = ATP, dGTP, TTP, and dATP) binding sites that govern which S is reduced (specificity site) and the overall rate of reduction (activity site). β2 contains the essential diferric-Y• cofactor. This unusually stable Y•, located at position 122, has a t1/2 of 4 days at 4 °C in contrast to the μs lifetimes observed for Y•s in solution. Nucleotide reduction occurs by a complex mechanism involving protein- and substrate-derived radicals, some details of which are summarized in Figure 2.1,3 The stable Y122• transiently oxidizes a cysteine (C439) in the catalytic site to a thiyl radical (S•), which reversibly abstracts a 3′-hydrogen atom (H•) from the NDP. The 3′-nucleotide radical rapidly loses water in the first irreversible step.1,3 The reducing equivalents are provided by two local cysteines (C225 and C462), and the resulting disulfide is re-reduced for subsequent turnovers, ultimately by thioredoxin (TR), thioredoxin reductase (TRR), and NADPH.

Figure 1.

A docking model of the E. coli α2β2 complex.2 α2 (pink and red) contains three nucleotide binding sites. β2 (light and dark blue) contains the diferric-Y• cofactor; residues 340 to 375 are not resolved in this structure. A peptide corresponding to the C-terminal 20 amino acids of β is bound to each α, a portion of which (residues 360-375) is resolved in the crystal structure (cyan). The “ATP cone” region of α, which contains the effector site that governs activity, is colored orange. This model separates Y122• in β2 from C439 in α2 by >35 Å. GDP (green), TTP (yellow) and the Fe2O core of the diferric cluster (orange) are shown in CPK space-filling models. Residues constituting the RT pathway (green) are shown in sticks.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of NDP reduction by RNR. The S• shown on C439 of α2 in the first reaction step is reversibly generated by Y122• in β2 by the mechanism shown in Figure 3a.

Uhlin and Eklund proposed a structure of the active α2β2 complex by in silico docking of crystal structures of the individual subunits (Figure 1).2 An atomic-resolution structure of an active class I RNR is still not available; however, recent experimental evidence supports this model (vide infra). The interaction between subunits is governed primarily by the flexible C-terminus of β2 (residues 360-375, Figure 1).4 The most provocative feature of the docking model was the >35 Å distance between Y122• in β2 and C439 in α2. The long distance suggested that direct oxidation of C439 by Y122• by a singlestep, electron tunneling mechanism would be too slow (kET of 10−7 to 10−9 s−1) to account for the turnover number of the E. coli RNR (~10 s−1).5 Accordingly, Uhlin and Eklund proposed that oxidation occurred by a hopping mechanism utilizing a specific pathway of conserved aromatic amino acids: Y122• ↔[W48?]↔ Y356 in β2 to Y731 ↔Y730 ↔ C439 in α2. The necessity of these residues for catalysis was established by site-directed mutagenesis experiments.6,7

The thermodynamics of Y or W oxidation require that proton transfer (PT) accompanies electron transfer (ET) at physiological pH. In RNR, these transfers are proposed to occur in a concerted fashion to prevent formation of high-energy, charged intermediates, thereby requiring a proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) at each step.8-10 In our model, orthogonal PCET steps are operative in β2, with the proton and electron transferring from the same donor to different acceptors, whereas co-linear PCET steps are operative in α2, with the proton and electron moving between the same donor/acceptor pair (Figure 3a).7,10,11 Our current model for the thermodynamics of radical transfer (RT) has evolved from studies in which the reduction potentials have been modulated at each Y on the pathway (Figure 3b).12-14 It holds that the potentials increase from Y122 < Y356 < Y731 ≈ Y730 ≤ C439, with the uphill forward oxidation driven by irreversible loss of H2O during nucleotide reduction. We now give an account of the results that have given rise to our RT mechanism and thermodynamic model.

Figure 3.

The Nocera/Stubbe elaboration of the Uhlin/Eklund model for RT in E. coli class Ia RNR. (a) The proposed movement of protons (blue arrows) and electrons (red arrows) at each step on the pathway. Distances (Å) are from structures of α2 and β2. E350 and Y356 are disordered in all β2 structures, and their positions are unknown. There is no direct evidence that W48 and D237 participate in RT and thus they are shown in gray. The distance between W48 and Y731 is modeled to be 25 Å. (b) The proposed relative reduction potentials of residues on the RT pathway from experiments using the indicated UAAs site-specifically incorporated in place of each Y. NH2Y has been incorporated at position 356, 730, or 731. Note that the absolute reduction potentials of these residues, the structures of which are shown in Figure 4, are not known, and the relative reduction potentials indicated are our best estimates given current knowledge (see Table 1 and Footnote 1).

Tools

Protein engineering

The study of RT is complicated by the fact that the PCET events are masked in the wild-type (wt) RNR by rate-limiting protein conformational changes that occur upon binding of nucleotides to α2β2 prior to RT.5 To perturb the native RT pathway in a predictable way, we have utilized two methods for site-specific incorporation of eight unnatural amino acids (UAAs) with altered reduction potentials and/or pKas into RNR (Figure 4a, Table 1). One method involved the semisynthesis of β2 by expressed protein ligation (EPL),15,16 whereas the second utilized in vivo nonsense codon suppression.13,17 Current research utilizes the latter method, as it may be applied to any residue in either subunit, minimizes mutations to the native enzyme relative to EPL, and has allowed isolation of 100 mg quantities of protein (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

UAAs incorporated into E. coli class Ia RNR. (a) Compounds 1-2 and 4-8 have been incorporated in position 356 of β2 by EPL, while compounds 1, 3-7 have been incorporated to sites in both α2 and β2 by in vivo nonsense suppression. (b) Purified protein yields achieved by in vivo nonsense suppression are given in parenthesis for each UAA at each position (in mg protein/g cells).

Table 1.

pKas and Eps of UAAs

| UAAa | pKab | Ep vs NHE (V)c | ΔEp vs Y/Y• (mV)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y | 9.9 | 0.83 | - |

| DOPA | 9.7 | 0.57 | −260 |

| NH2Y | ~10 | 0.64 | −190 |

| 3,5-F2Y | 7.2 | 0.77 | −60 |

| 2,3-F2Y | 7.8 | 0.86 | +30 |

| 2,3,5-F3Y | 6.4 | 0.86 | +30 |

| 2,3,6-F3Y | 7.0 | 0.93 | +100 |

| 2,3,5,6-F4Y | 5.6 | 0.97 | +140 |

| NO2Y | 7.2 | 1.02 | +190 |

For Y, NO2Y, and FnYs, measurements made on N-acetyltyrosinamide forms.

The solution pKas reported here are perturbed by <+1 unit at positions 356, 730, and 731 and by >+2.5 units at position 122.

At pH 7, as reported in references 15,17-19 and references therein.

Kinetic techniques and spectroscopic methods

The reactivity of a mutant protein, once isolated, is studied by rapid kinetic techniques to unveil radical intermediates. In a typical experiment, a solution containing a mutant subunit (α2 or β2) and S is rapidly mixed with a solution containing the complementary wt subunit and E, and the reaction monitored with millisecond time resolution for loss of Y122• and formation of a new radical(s) (Figure 5). Changes can be monitored continuously by stopped-flow (SF) UV-vis or fluorescence spectroscopies, or discontinuously using either a rapid freeze quench (RFQ) apparatus and paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy or a rapid chemical quench (RCQ) apparatus and scintillation counting of a radiolabeled product.

Figure 5.

Experimental design, kinetic techniques, and detection methods for studying RT.

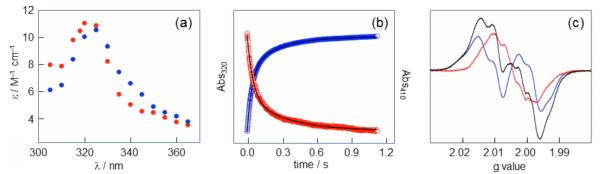

Figure 6 shows the spectroscopic signatures of the stable diferric-Y122• in β2. The cofactor gives rise to a UV-vis spectrum with a sharp feature at 411 nm (Figure 6a) and an EPR spectrum (9 GHz) with hyperfine couplings associated with one of its two β-methylene protons and its 3,5 aromatic protons (Figure 6b). The g tensors [gx, gy, gz) determined by high-field (HF) EPR (94 or 140 GHz) are particularly informative, as gx is very sensitive to the electrostatic (i.e., H-bonding) environment of the Y• (Figure 6c). EPR and related methods, including pulsed electron-electron double resonance (PELDOR)20 and HF [2H]-electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR)21 spectroscopies, have allowed characterization of stable and transient radicals observed in engineered RNRs. Together, these methods have provided tools for the study of RT in RNR.

Figure 6.

Spectroscopic characterization of the diferric-Y122• cofactor from E. coli class Ia RNR. (a) The UV-vis spectrum has contributions from the diferric cluster at 325 and 365 nm and Y122• at 411 nm. (b) The 9 GHz EPR spectrum of Y122• with the origin of its hyperfine couplings indicated. (c) The 140 GHz EPR spectrum of Y122• resolves three distinct g tensors. Adapted from reference 22.

Complexities in studying E. coli class Ia RNR

Two unresolved issues have complicated our mechanistic studies. The first is the apparent half-sites reactivity of RNR,5,19 a phenomenon in which radical initiation occurs initially within a single α/β pair and a chemical or conformational step during or subsequent to product formation then triggers RT on the second α/β pair.5 The second RT event is prevented when a radical is trapped in the first α/β pair by replacing the S with a mechanism-based inhibitor20 or by modulating the energetics of RT using UAAs.19,23 The second issue concerns the stoichiometry and distribution of Y122• within β2. The diferric-Y• in β2 is self-assembled from apo-β2 to give ~1.2 Y•/β2 and while the loading of radical in each β monomer is unknown, our in vitro biochemical studies suggest it is evenly distributed (0.6 Y•/β).

Evidence for a pathway of redox-active amino acids

Our earliest experiments sought to validate the proposed pathway and the redox reactivity of its constituents (Figure 3a). The role of Y356 in the C-terminal tail of β2 was first studied, as its position relative to other residues is unknown (Figure 1). Using EPL, Y356 was replaced with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA, 2, Figure 4a), which has a peak potential (Ep) 260 mV lower than Y (pH 7, Table 1) and was utilized as a radical trap. Reaction of Y356DOPA-β2 with wt-α2, S, and E resulted in loss of 50% of the initial Y122• concomitant with formation of an equal amount of DOPA356•.19 No DOPA356• was observed in the absence of the second subunit or nucleotides. The kinetics of DOPA356• formation involved multiple phases, the majority of which were kinetically competent (i.e., faster than the wt kcat); however, the mutant was unable to make dNDP. These studies demonstrated that nucleotides are required to trigger RT and provided the first evidence for conformation changes associated with RT.

Our attention turned to investigating the roles of Y731 and Y730 in α2. In collaboration with the Schultz lab, an orthogonal tRNA synthetase (RS) that specifically recognizes 3-aminotyrosine (NH2Y, 3, Figure 4a] was evolved and was used to incorporate NH2Y to positions 730 and 731 of α2 and 356 of β2 (collectively called NH2Y-RNRs). With an Ep 190 mV lower than Y (pH 7, Table 1], NH2Y was expected to behave like DOPA, as a radical sink. Indeed, reaction of each of the three NH2Y-RNRs with the second subunit, S, and E resulted in the generation of an NH2Y• kinetically coupled to Y122• loss, as measured by SF UV-vis and EPR spectroscopy (Figure 7].17,24 Radical formation again required the presence of both subunits and nucleotides, was biphasic, and was kinetically competent for all S and E pairs for all three NH2Y-RNRs. In contrast to DOPA, however, all NH2Y-RNRs were active in dNDP production. Additional experiments revealed that NH2Y• was formed only when the other Ys in the wt RT pathway were intact. This result was interpreted as evidence that NH2Y• formation is pathway-dependent and not the indirect consequence of introducing a thermodynamic trap into the protein.25 Thus, results obtained with DOPA- and NH2Y-RNRs support the participation of three Ys acting as redox relays linking Y122• in β2 to C439 in α2.

Figure 7.

Spectroscopic characterization of NH2Y•s. (a) A point-by-point reconstruction of the absorbance spectra of NH2Y730• (blue) and NH2Y731• (red) formed 1.5 s after reacting Y731NH2Y-α2 (or Y730NH2Y-α2) with wt-β2, CDP, and ATP. (b) Averaged single-wavelength SF UV-vis traces for the Y731NH2Y-α2 reaction described in (A). Loss of Y122• (red, 410 nm] correlates with the formation of NH2Y731• (blue, 320 nm]. Biexponential fits to the data are shown as black lines. (c) The 9 GHz EPR spectrum (black) of an identical reaction frozen after 10 s is a ~1:1 composite of residual Y122• (blue) and NH2Y731• (red). Figure adapted from reference 17.

Evidence for an active α2 β2 complex resembling the docking model

The ability to generate moderately stabilized NH2Y•s (t1/2 on min scale) at positions along the pathway coupled with the half-sites reactivity of RNR allowed us to test whether the docking model (Figure 1)2 is an accurate representation of the active RNR. Specifically, PELDOR spectroscopy, a technique that detects weak dipolar interactions between paramagnetic species separated by 20-80 Å, was utilized to measure diagonal distances between a radical generated on the pathway in one α/β pair and the Y122• on the second α/β pair (Figure 8). The distances measured between Y122• and DOPA356• provided the first structural constraint on the location of this residue within α2β2. Measurements between Y122• and NH2Y731•, NH2Y730•, or an active-site nitrogen-centered radical formed upon reaction with the mechanism-based inhibitor 2′-azido-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-diphosphate (N3UDP)1 were all in excellent agreement with the distances predicted by the docking model.20,23

Figure 8.

Validating the docking model by PELDOR spectroscopy. By exploiting the half-sites reactivity of RNR, diagonal distances between Y122• on one α/β pair and DOPA356•, NH2Y731•, NH2Y730•, and an active-site N• on the second α/β pair have been measured.20,23 The pathway residues and S were built in from the docking model,2 in which Y356 is invisible.

We have also observed that generation of an NH2Y• on the pathway induces a tight, kinetically stable α2/β2 interaction.26 At low α2 and β2 concentrations in the presence of S and E pairs, the wt α2/β2 interaction is weak (Kd = 50-400 nM) and transient (koff ~50-100 s−1).4,27 In contrast, under conditions that generate NH2Y730•, the binding between Y730NH2Y-α2 and wt-β2 is tight (Kd = 7 nM), cooperative, and long-lived (koff ~10−3 s−1). The stable complex has been structurally characterized by electron microscopy (30 Å resolution) and was found to be consistent with the docking model, providing the first direct visualization of RNR in a catalytically relevant state.26

Mechanism of long-range PCET in E. coli RNR

pKas of pathway residues

UAAs with perturbed pKas (Figure 4a, 1 and 4-8, and Table 1) provide a means to study the nature of the PT coupled to ET (i.e., orthogonal vs. co-linear PCET, Figure 3a). To interpret the results of such experiments, we initially determined the extent to which the pKas of the pathway Ys are modulated by their local protein environment using NO2Y (Figure 4, 1). The absorbance features of the NO2Y phenolate (NO2Y−, λmax = 430 nm, ε = 4,200 cm−1 M−1) allowed titration of a single residue in the 258 kDa complex of α2β2, S and E. When incorporated at position 356 of β2 and 730 and 731 of α2, the pKa of NO2Y was increased by ≤1 pH unit compared that of NO2Y in solution (7.2).15,28 In contrast, NO2Y incorporated at position 122 of β2 revealed an increase in pKa by >2.5 units,28 suggesting that the hydrophobic pocket surrounding the cofactor confers unique properties on Y122 relative to the other pathway Ys. X-ray structures of α2 and β2 mutants containing NO2Y revealed minimal changes in comparison to structures of the respective wt subunits.28,29

Mechanism of RT in β2

Our proposal for orthogonal PCET in β2 (Figure 3a) was first examined by replacing Y356 with 2,3-F2Y (5, Figure 4a), which has a pKa of 7.8.30 A pH rate profile of dCDP formation with Y356(2,3)F2Y-β2 and wt-α2 revealed that the complex was active from pH 6-9, indicating that ET through position 356 does not require PT and suggesting that an H-bond to Y356 is not necessary for RT through that position.30 Subsequently, a complete series of FnYs (4-8, Figure 4a) with pKas ranging from 5.6-7.8 (Table 1) were incorporated at position 356. In no case was a correlation between enzyme activity and protonation state observed, consistent with an orthogonal PCET mechanism.16

An orthogonal PCET mechanism involving 356 suggests the importance of a proton acceptor. This was proposed to be the conserved acid E350 in the C-terminus of β2 (Figure 3a)6 after Sjöberg and colleagues observed that E350A-β2 is catalytically inactive despite maintaining its ability to bind α2 and to assemble cofactor.6 Furthermore, reactions between E350A/Y356NH2Y-β2 and wt-α2, or E350A-β2 and Y731NH2Y-α2, fail to generate NH2Y•, indicating that the E350 mutation prevents NH2Y oxidation at positions 356 and 731.14 While these results highlight the importance of E350 in mediating RT through position 356, the inactivity of these and the E350D- and E350Q-β2 mutants prevents drawing strong mechanistic conclusions.

Mechanistic insight into the first step of RT, reduction of Y122•, has been investigated in collaboration with the Bollinger/Krebs lab.31 The model (Figure 3a) proposes that Y122• reduction is coupled to PT from a Fe1-bound water. To test this hypothesis, the Mössbauer spectrum of the resting diferric-Y122• in [57Fe]-loaded wt-β2, wt-α2, and E was compared to that of the Y•-reduced cofactor generated upon reaction of β2, α2 and E with 2′-N3UDP.1 The similarities in the isomer shifts and the differences in the quadrupole splitting parameter associated with Fe1 suggest no change in the Fe oxidation state and a change in ligation to Fe1 from a bound water to a bound hydroxide, consistent with PT from this ligand to the reduced Y122.31

Mechanism of RT in α2

Experimental evidence for co-linear PCET within α2, suggested by the proximity of pathway residues in the α2 structure, was obtained by studying light-initiated RT in systems in which the β2 subunit is replaced by a photopeptide (Figure 9).7,10 The peptide corresponds to the C-terminal 19 amino acids (356-375) of β (βC19) with either a Y or FnY at position 356 and a photooxidant (PO) such as benzophenone (BP), anthraquinone (Anq), or Re(bpy)(CO)3CN ([Re]) appended to the N-terminus.10,11 Pairing different POs with different Y analogs allows modulation of the driving force of oxidation at position 356 and of radical injection into α2. Upon excitation, the PO generates a transient radical at 356, a small fraction of which migrates into α2 (Figure 9). The time-resolved formation and decay of the 356 radical is monitored by transient absorption spectroscopy.

Figure 9.

Photo-initiated radical propagation in PO-Y-βC19 photopeptides. A photooxidant (PO, black circle) is appended to the N-terminus of a peptide corresponding to residues 356-375 of β2 (βC19, cyan), with either Y or FnY at position 356. Light excitation (step 1) induces oxidation of the residue at position 356 (2), a fraction of which is reduced by Y731 of α2 (3). The photopeptide/wt-α2 complex is capable of generating dNDP (4), providing direct evidence for radical injection from the peptide. Figure constructed from PDB ID 1RLR.2

Photolysis of either [BP]- or [Anq]-Y-βC19 with wt-α2, [14C]-CDP, and ATP under single-turnover conditions generated 0.25 dCDP/α2, demonstrating the chemical competence of the system.32 The redox-inert Y730F-α2 prevented dCDP formation, supporting co-linear transport of an H+ and e−.32 The light-initiated reaction of [Re]-2,3,6-F3Y-βC19 with wt-α2 was compared to that with various α2 mutants to investigate whether the photogenerated F3Y356• could initiate RT into α2. Radical injection occurred with a ket of ~105 s−1 in both the wt enzyme and C439S mutant, but was not observed in the Y731F and Y730F variants. These results suggest that the intact Y731/Y730 dyad and its associated H-bonding network are necessary for RT.33 Experiments are underway to test this hypothesis with [Re]-C355S-β2, a mutant β2 in which the PO is attached at position 355, in the intact α2β2 complex.34

Additional support for co-linear PCET within α2 has been obtained from studies of the NH2Y730• formed upon reaction of Y730NH2Y-α2 with wt-β2, CDP, and ATP by HF-EPR and ENDOR spectroscopies. Multifrequency EPR analysis of [14N]- and [15N]-NH2Y730• in H2O and D2O allowed for accurate simulations of experimental spectra and revealed an unusually low gx value of 2.0052, suggesting the importance of a local H-bonding environment.35 Analysis of ND2Y730• using HF [2H]-ENDOR spectroscopy (Figure 10), combined with structural information24 and DFT calculations, allowed assignment of exchangeable protons in the immediate vicinity of the NH2Y730•.21 These studies revealed strong intramolecular H bonds from the NH2 group, two moderate H-bonding interactions (presumably with the adjacent pathway residues, Y731 and C439), and a weaker interaction likely associated with an ordered water molecule. These results support a co-linear PCET mechanism within α2 by demonstrating a structured H-bonding network in the active α2β2 complex.21

Figure 10.

The 94 GHz [2H]-MIMS ENDOR spectrum of NH2Y730• in the active α2β2 complex reveals the details of its intra- and intermolecular H-bonds. Experimental data are shown in black and a simulation in red. The two prominent peaks centered around 0.6 MHz fall in a region expected for coupled H bonds. The detailed analysis of the experimental spectrum and its simulation is described in reference 21.

Mapping the thermodynamic landscape of the PCET pathway

A barrier to the RT pathway: NO2Y or FnY

UAAs incorporated into RNR alter the thermodynamics from 260 mV easier to oxidize (DOPA) to 190 mV harder to oxidize (NO2Y) than Y based on Ep measurements near physiological pH (Table 1). When the Y at position 356, 731, or 730 is replaced with NO2Y, the resulting mutant is inactive indicating that NO2Y cannot be oxidized by other pathway radicals and hence cannot support RT. A series of FnYs (4-8, Figure 4a, Table 1) incorporated at position 356 of β2 by EPL provided access to Eps that varied from −50 mV to +250 mV relative to Y in the pH 6-9 range in which RNR is active (Figure 11).18 pH rate profiles of these mutants demonstrated that their activities fell into three regimes based on the difference in Ep (ΔEps) between the FnY (or FnY−)/FnY• and Y/Y• couples. Y356FnY-β2s had activities resembling wt-β2 at ΔEps <80 mV, whereas they were inactive at ΔEps <200 mV, consistent with the results of NO2Y mutants. In the range from 80-200 mV, Y356FnY-β2s exhibited measurable activities that decreased with increasing ΔEp.16

Figure 11.

Solution peak potentials (Eps) of Y, W, and UAAs blocked with N-acetyl and C-amide functionalities.15,18

A sink in the RT pathway: DOPA or NH2Y

Substitution of pathway residues by DOPA or NH2Y (2 and 3, Figure 4a) has allowed us to explore the consequence of lowering the potential at positions on the pathway by 260 and 190 mV, respectively (Table 1). As noted above, Y356DOPA-β2 is catalytically inactive, presumably due to the inability of DOPA356• to oxidize Y731. We expected that NH2Y-RNRs would also be inactive, however these three mutants possessed 3-12% of the activity of their corresponding wt subunits.17,24 (Footnote 1: This result was unexpected, as the ΔEp between Y and NH2Y is near the 200 mV threshold observed to shut down RT. However, the Eps reported herein (Table 1)15,17-19 have been measured by various methods by different researchers, and thus significant error could exist in our calculated ΔEps. We are collaborating with the Koppenol lab to re-measure the potentials of these UAAs to obtain a single set of reliable values. Further error arises from the fact that Ep values are sensitive to the reaction conditions under which they were measured, and thus the observed Eps may differ significantly from true reduction potentials (E°s).) The combination of kinetically competent NH2Y• formation and catalytic dNDP formation in NH2Y-RNRs present an opportunity to measure solvent isotope effects at individual steps in the RT pathway and during NDP reduction, providing insight on mechanistic details that are kinetically masked in the wt enzyme.14 In summary, activity measurements of RNRs containing UAAs indicate that the thermodynamics of RT can be modulated by ≤±200 mV relative to the native pathway at positions 356, 731, and 730 while retaining some enzymatic activity.

Increasing the driving force of RT at position 122: NO2Y and FnYs

In an effort to characterize the native Y• intermediates, we replaced Y122 with NO2Y and FnYs (1 and 4-7, Figure 4a). We anticipated the ability to generate radicals of NO2Y and FnYs at this position given the unique mechanism of diferric-Y122• assembly in the wt enzyme, which utilizes a strongly oxidizing Fe3+/Fe4+ intermediate (“X,” Figure 12).7 A three-syringe, double-mixing apparatus was employed for these experiments in which FeII-loaded Y122NO2Y-β2 was rapidly mixed with O2-saturated buffer to generate NO2Y122• (1.2 eq/β2, t1/2 ~40 s at 25 °C) on the first syringe drive, followed immediately by reaction of this short-lived NO2Y122• with wt-α2, S, and E on the second syringe drive (Scheme 1, step 1).29 The reaction was monitored by SF, RFQ-EPR, RFQ-PELDOR and RCQ methods (Figure 5) and the results are summarized in Scheme 1.29 After assembly of the active cofactor, NO2Y122• is rapidly reduced (>100 s−1) in the first step of RT to generate the phenolate (NO2Y122−) rather than the anticipated phenol, indicating an uncoupling of PT from ET. All subsequent steps, including formation of dCDP and a new Y•(s), occurred with similar rate constants (>100 s−1). The ability to detect dCDP and new Y• formation at rate constants 10- to 50-fold faster than the wt kcat indicated that disruption of the PT/ET coupling in the first step bypassed the conformational change that is rate-determining in the wt enzyme. Only 0.6 eq dCDP/β2 and 0.6 eq Y•/β2 were generated in this process, indicating that the mutant enzyme (1.2 NO2Y122•/β2) could perform only a single turnover with half-sites reactivity, presumably due to inability to reoxidize the NO2Y122− to NO2Y122• during reverse RT.

Figure 12.

Assembly of the diferric-Y122• (or NO2Y122• or FnY122•) cofactor from diferrous-β2, O2 and reductant.

Scheme 1.

Kinetic model for radical initiation in the reaction of Y122NO2Y-β2 with wt-α2, S, and E.29

The results of additional studies of NO2Y-containing β2s with either additional mutations of pathway residues (Y-to-F or Y-to-3,5-F2Y) or globally labeled β-[2H]-Ys, in conjunction with HF EPR and PELDOR spectroscopies, indicated that the observed Y• is generated during reverse RT and exists as an equilibrium of radicals at positions 356, 731, and 730 in ~10:1:1 ratio.12,29 These findings provide the basis for the relative positioning of Y356, Y731, and Y730 in the proposed thermodynamic landscape of the RT pathway (Figure 3b).12

To explore reactivity in the ~200 mV regime separating NO2Y and Y, a series of FnYs (4-7, Figure 4a) were incorporated in place of Y122. Assuming that Y122FnY-β2s experience a pka perturbation similar to that of NO2Y122 (>2.5 units),28 all FnYs would remain protonated at pH 7.6 and would vary from 50 mV easier to 100 mV harder to oxidize than Y (Figures 3b and 11).18 Using an evolved, polyspecific FnY-RS, four Y122FnY-β2s were isolated, and the assembly and stability of their FnY122•s were spectroscopically characterized.13,14 Their EPR spectra feature hyperfine couplings of the radical to the fluorine nuclei, giving rise to sharp low- and high-field features that facilitate spectral deconvolution of FnY122•s from pathway Y•s (Figure 13a).13 All Y122FnY-β2s are active in the steady-state with 10-100 % the activity of wt-β2.14 When the driving force of RT is raised relative to Y, reaction of Y122FnY-β2s with wt-α2 (or Y731F-α2), S, and E resulted in loss of FnY122• concomitant with the generation of a new radical, hypothesized to be Y356• generated during forward RT (Figure 13b).13,14 The kinetics of new radical formation and dCDP production have been studied for the reaction of Y122(2,3,5)F3Y-β2 with wt-α2, CDP, and ATP, and indicate that Y356• formation is kinetically competent relative to dCDP formation.14

Figure 13.

(a) X-band EPR spectra (77 K) for E. coli Y122• and FnY122•s normalized for radical concentration. Dashed lines highlight the increased spectral width of the FnY122•s.13,14 (b) EPR spectrum of the reaction of Y122(2,3,5)F3Y-β2, wt-α2, CDP, and ATP quenched at 25 s. The reaction spectrum (black) is a composite of two species: 2,3,5-F3Y122• (pink) and a new radical (blue, magnified in inset), assigned as Y356•.13

Finally, the ability to monitor oxidation of Y356 by NO2Y122• or FnY122•s has allowed us to address the function of W48 (Figure 3a).2,7 This residue has been shown to participate during in vitro cofactor assembly, but its role in long-range RT has not been established. Preliminary studies of the reactivity of Y122NO2Y/Y356F-β2 or Y122(2,3,5)F3Y/Y356F-β2 double mutants provided no evidence for the formation of a discrete W48•/W48•+ intermediate during in RT, although it is possible that W48 plays an important role in conformational gating.13,14,29

From the studies conducted to date, a thermodynamic landscape for the RT pathway is emerging (Figure 3b). This model indicates that position 122 is the pathway minimum, however, detection of Y356• in the reaction with Y122(2,3,5)F3Y-β2 as a radical initiator suggests that the thermodynamic difference between position 122 and 356 is small and that the stability of Y122• may be kinetic in origin. W48 is colored in gray, as we currently have no evidence in support of its participation as a discrete radical intermediate. The three transiently oxidized Ys are harder to oxidize than Y122, with Y731 and Y730 50-100 mV harder to oxidize than Y356 and roughly isoenergetic with one another.12 Finally, C439 is placed at a reduction potential quite similar to or slightly elevated above the 730/731 dyad based on the solution reduction potential of glutathione radical at neutral pH.36 In our model, the forward RT pathway is thus uphill, and C439 oxidation is driven by the rapid, irreversible loss of water in the second step of nucleotide reduction (Figure 2),1,3 and the reverse RT pathway is downhill and rapid.

Conclusions

This account summarizes the results of recent mechanistic studies on mutant E. coli class Ia RNRs containing unnatural Y analogs at the proposed sites of stable and transient Y• formation on the RT pathway. Specifically, the results obtained from unnatural DOPA-, NH2Y-, NO2Y- and FnYs-RNRs and light-initiated photo-RNRs, were used to establish: (1) that there exists a specific pathway containing a minimum of four Ys involved in long-range RT over 35 A across a compact, globular α2β2 resembling Uhlin and Eklund’s docking model; (2) that RT occurs by orthogonal and co-linear PCET transfers in the β2 and α2 subunits, respectively; (3) that the overall thermodynamics of RT are only slightly uphill in the forward direction, with several of the intervening steps being nearly isoenergetic; (4) that the individual RT steps and the chemistry of nucleotide reduction are fast (~105 s−1 and >100 s−1, respectively), despite being kinetically masked by several conformational changes (10-100 s−1) that occur when nucleotides bind to α2β2; and (5) that the rate-limiting conformational changes likely target the RT pathway and its tightly coupled proton and electron transfers.

CONSPECTUS.

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) catalyze the conversion of nucleotides to 2′-deoxynucleotides and are classified on the basis of the metallo-cofactor used to conduct this chemistry. The class Ia RNRs initiate nucleotide reduction when a stable diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y•, t1/2 of 4 days at 4 °C) cofactor in the β2 subunit transiently oxidizes a cysteine to a thiyl radical (S•) in the active site of the α2 subunit. In the active α2β2 complex of the class Ia RNR from E. coli, this oxidation has been proposed to occur reversibly over 35 Å by a radical hopping mechanism along a specific pathway comprising redox-active aromatic amino acids: Y122• ↔ [W48?] ↔ Y356 in β2 to Y731 ↔ Y730 C439 in α2, with each step necessitating a proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET). Protein conformational changes constitute the rate-limiting step in the overall catalytic scheme, thereby kinetically masking the detailed chemistry of the PCET steps. Technology has evolved to allow the site-selective replacement of the four pathway Ys with unnatural Y analogs. Rapid kinetic techniques combined with multi-frequency electron paramagnetic resonance, pulsed electron-electron double resonance, and electron nuclear double resonance spectroscopies have facilitated analysis of stable and transient radical intermediates in these mutants, thereby beginning to reveal the mechanistic underpinnings of the radical transfer (RT) process.

This account summarizes recent mechanistic studies on mutant E. coli RNRs containing the following Y analogs: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) or 3-aminotyrosine (NH2Y), both thermodynamic radical traps; 3-nitrotyrosine (NO2Y), a thermodynamic barrier and probe of local environmental perturbations to the phenolic pKa; and fluorotyrosines (FnYs, n = 2 or 3), dual reporters on local pKas and reduction potentials. These studies have established the existence of a specific pathway spanning 35 Å within a globular α2β2 complex that involves one stable (position 122) and three transient (positions 356, 730, and 731) Y•s. Our results also support that RT occurs by an orthogonal PCET mechanism within β2, with Y122• reduction accompanied by proton transfer from an Fe1-bound water in the diferric cluster and Y356 oxidation coupled to an off-pathway proton transfer likely involving E350. In α2, RT likely occurs by a co-linear PCET mechanism, as evidenced from studies of light-initiated radical propagation from photopeptides mimicking the β2 subunit to the intact α2 subunit, and by [2H]-ENDOR spectroscopic analysis of the hydrogen-bonding environment surrounding a stablized NH2Y• formed at position 730. Additionally, studies on the thermodynamics of the RT pathway reveal that the relative reduction potentials decrease according to Y122 < Y356 < Y731 ≈ Y730 ≤ C439, and that the pathway in the forward direction is thermodynamically unfavorable, with C439 oxidation likely driven by rapid, irreversible loss of water during the nucleotide reduction process. Kinetic studies of radical intermediates reveal that RT is gated by conformational changes occurring on the order of > 100 s−1 in addition to the changes that are rate-limiting in the wt enzyme (~10 s−1). The rate constant of one of the PCET steps is ~105 s−1, as measured in photo-initiated experiments.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many researchers with whom we have fruitfully collaborated on this project, and we regret that space constraints have prevented us from recognizing each of them and their unique contributions in this account. We thank Arturo Pizano for assistance with Figure 9. This work was supported by the NIH grants GM47274 (to DGN) and GM29595 (to JS).

ABBREVIATIONS

- α2

RNR large subunit

- β2

RNR small subunit

- E

effector

- Ep

peak potential

- ET

electron transfer

- HF

high-field

- N3UDP

2′-azido-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-diphosphate

- PCET

proton-coupled electron transfer

- PO

photooxidant

- PT

proton transfer

- RT

radical transfer

- S•

cysteine radical

- S

substrate

- UAA

unnatural amino acid

- wt

wild-type

- Y•

tyrosyl radical

Biography

Ellen C. Minnihan conducted graduate research in the Stubbe lab and earned her PhD in Chemistry from MIT in 2012.

Daniel G. Nocera is the Patterson Rockwood Professor of Energy at Harvard University. His research focuses on the study of PCET as it pertains to the biology of nucleotide metabolism and energy conversion.

JoAnne Stubbe, the Novartis Professor of Chemistry and Professor of Biology at MIT, has dedicated her career to the study of the mechanisms of ribonucleotide reductases and other enzymatic systems.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- (1).Stubbe J, van der Donk WA. Protein radicals in enzyme catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:705–762. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Uhlin U, Eklund H. Structure of ribonucleotide reductase protein R1. Nature. 1994;370:533–539. doi: 10.1038/370533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Licht S, Stubbe J. Mechanistic investigations of ribonucleotide reductases. Compr. Nat. Prod. Chem. 1999;5:163–203. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Climent I, Sjöberg BM, Huang CY. Carboxyl-terminal peptides as probes for Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase subunit interaction: kinetic analysis of inhibition studies. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5164–5171. doi: 10.1021/bi00235a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ge J, Yu G, Ator MA, Stubbe J. Pre-steady-state and steady-state kinetic analysis of E. coli class I ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10071–10083. doi: 10.1021/bi034374r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Climent I, Sjöberg BM, Huang CY. Site-directed mutagenesis and deletion of the carboxyl terminus of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase protein R2 - effects on catalytic activity and subunit interaction. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4801–4807. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Stubbe J, Nocera DG, Yee CS, Chang MCY. Radical initiation in the class I ribonucleotide reductase: long-range proton-coupled electron transfer? Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2167–2201. doi: 10.1021/cr020421u. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cukier RI, Nocera DG. Proton-coupled electron transfer. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1998;49:337–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.49.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mayer JM. Proton-coupled electron transfer: a reaction chemist’s view. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2004;55:363–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.55.091602.094446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Reece SY, Hodgkiss JM, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Proton-coupled electron transfer: the mechanistic underpinning for radical transport and catalysis in biology. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2006;361:1351–1364. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1874. and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Reece SY, Nocera DG. Proton-coupled electron transfer in biology: results from synergistic studies in natural and model systems. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:673–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.080207.092132. and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yokoyama K, Smith AA, Corzilius B, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. Equilibration of tyrosyl radicals (Y356•, Y731•, Y730•) in the radical propagation pathway of the Escherichia coli class Ia ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18420–18432. doi: 10.1021/ja207455k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Minnihan EC, Young DD, Schultz PG, Stubbe J. Incorporation of fluorotyrosines into ribonucleotide reductase using an evolved, polyspecific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15942–15945. doi: 10.1021/ja207719f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Minnihan EC. Ph.D. Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yee CS, Seyedsayamdost MR, Chang MCY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Generation of the R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase by intein chemistry: insertion of 3-nitrotyrosine at residue 356 as a probe of the radical initiation process. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14541–14552. doi: 10.1021/bi0352365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Seyedsayamdost MR, Yee CS, Reece SY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. pH rate profiles of FnY356-R2s (n = 2, 3, 4) in Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase: evidence that Y356 is a redox-active amino acid along the radical propagation pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1562–1568. doi: 10.1021/ja055927j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Seyedsayamdost MR, Xie J, Chan CT, Schultz PG, Stubbe J. Site-specific insertion of 3-aminotyrosine into subunit α2 of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase: direct evidence for involvement of Y730 and Y731 in radical propagation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15060–15071. doi: 10.1021/ja076043y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Seyedsayamdost MR, Reece SY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted fluorotyrosines: new probes for enzymes that use tyrosyl radicals in catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1569–1579. doi: 10.1021/ja055926r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J. Site-specific replacement of Y356 with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine in the β2 subunit of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2522–2523. doi: 10.1021/ja057776q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bennati M, Robblee JH, Mugnaini V, Stubbe J, Freed JH, Borbat P. EPR distance measurements support a model for long-range radical initiation in E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15014–15015. doi: 10.1021/ja054991y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Argirevic T, Riplinger C, Stubbe J, Neese F, Bennati M. ENDOR spectroscopy and DFT calculations: Evidence for the hydrogen-bond network within a2 in the PCET of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:17661–17670. doi: 10.1021/ja3071682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gerfen GJ, Bellew BF, Un S, Joseph M, Bollinger J, Stubbe J, Griffin RG, Singel DJ. High-frequency (139.5 GHz) EPR spectroscopy of the tyrosyl radical in Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6420–6421. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Seyedsayamdost MR, Chan CT, Mugnaini V, Stubbe J, Bennati M. PELDOR spectroscopy with DOPA-β2 and NH2Y-α2s: distance measurements between residues involved in the radical propagation pathway of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15748–15749. doi: 10.1021/ja076459b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Minnihan EC, Seyedsayamdost MR, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. Kinetics of radical intermediate formation and deoxynucleotide production in 3-aminotyrosine-substituted Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9430–9440. doi: 10.1021/ja201640n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Minnihan EC, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J. Use of 3-aminotyrosine to examine the pathway dependence of radical propagation in Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12125–12132. doi: 10.1021/bi901439w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Minnihan EC, Ando N, Brignole EJ, Olshansky L, Chittuluru J, Asturias F, Drennan CL, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Generation of a stable, aminotyrosyl radical-induced α2β2 complex of E. coli class Ia RNR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. US A. 2013;110:3835–3840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220691110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hassan AQ, Olshansky L, Yokoyama K, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. In revision.

- (28).Yokoyama K, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. Site-specific incorporation of 3-nitrotyrosine as a probe of pKa perturbation of redox-active tyrosines in ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8385–8397. doi: 10.1021/ja101097p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yokoyama K, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. A hot oxidant, 3-NO2Y122 radical, unmasks conformational gating in ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15368–15379. doi: 10.1021/ja1069344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Yee CS, Chang MCY, Ge J, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. 2,3-difluorotyrosine at position 356 of ribonucleotide reductase R2: A probe of long-range proton-coupled electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10506–10507. doi: 10.1021/ja036242r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wörsdörfer B, Conner DA, Yokoyama K, Seyedsayamdost M, Jiang W, Stubbe J, Martin J, Bollinger J, Krebs C. Function of the diiron cluster in Escherichia coli class Ia ribonucleotide reductase in proton-coupled electron transfer. In revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (32).Reece SY, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Photoactive peptides for light-initiated tyrosyl radical generation and transport into ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8500–8509. doi: 10.1021/ja0704434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Holder PG, Pizano AA, Anderson BL, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Deciphering radical transport in the large subunit of class I ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1172–1180. doi: 10.1021/ja209016j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Pizano AA, Lutterman DA, Holder PG, Teets TS, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Photo-ribonucleotide reductase β2 by selective cysteine labeling with a radical phototrigger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. US A. 2011;109:39–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115778108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Seyedsayamdost MR, Argirevic T, Minnihan EC, Stubbe J, Bennati M. Structural examination of the transient 3-aminotyrosyl radical on the PCET pathway of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase by multifrequency EPR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15729–15738. doi: 10.1021/ja903879w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Madej E, Wardman P. The oxidizing power of the glutathione thiyl radical as measured by its electrode potential at physiological pH. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;462:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]