Abstract

Objectives

The goals of this study were (i) to report the prevalence and nature of sleep disturbances, as determined by clinically significant insomnia symptoms, in a sample of African-American breast cancer survivors; (ii) to assess the extent to which intrusive thoughts about breast cancer and fear of recurrence contributes to insomnia symptoms; and (iii) to assess the extent to which insomnia symptoms contribute to fatigue.

Methods

African-American breast cancer survivors completed surveys pertaining to demographics, medical history, insomnia symptoms, and intrusive thoughts about breast cancer, fear of cancer recurrence, and fatigue. Hierarchical regression models were performed to investigate the degree to which intrusive thoughts and concerns of cancer recurrence accounted for the severity of insomnia symptoms and insomnia symptom severity's association with fatigue.

Results

Forty-three percent of the sample was classified as having clinically significant sleep disturbances. The most commonly identified sleep complaints among participants were sleep maintenance, dissatisfaction with sleep, difficulty falling asleep, and early morning awakenings. Intrusive thoughts about breast cancer were a significant predictor of insomnia symptoms accounting for 12% of the variance in insomnia symptom severity. After adjusting for covariates, it was found that insomnia symptom severity was independently associated with fatigue accounting for 8% of variance.

Conclusions

A moderate proportion of African-American breast cancer survivors reported significant problems with sleep. Sleep disturbance was influenced by intrusive thoughts about breast cancer, and fatigue was associated with the severity of participants' insomnia symptoms. This study provides new information about sleep-related issues in African-American breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: sleep, African-American, breast, cancer, survivors

Introduction

Reports indicate that sleep disturbances are highly prevalent in breast cancer survivors [1]. In fact, a significant proportion of breast cancer survivors experience problems with sleep years after diagnosis [2, 3]. In addition, sleep problems are a significant burden among patients in terms of functional impairment and reduced quality of life [4]. Sleep impairment has also been associated with increased mortality risk [5, 6], and adverse cardiovascular [7–9] and metabolic consequences [10, 11].

Despite a growing interest in sleep patterns among cancer patients, most studies have not examined this issue in African-American women, a group known to have high breast cancer rates and a high prevalence of suboptimal sleep [12–14]. For example, Hall et al. [15] reported that African-American noncancer patients showed reduced sleep duration and continuity, and poorer subjective sleep quality compared with Caucasians.

Based on this information, research addressing sleep in African-American breast cancer survivors is warranted. A study by Northouse et al. [16] queried 98 African-American breast cancer survivors who were approximately 4 years post-diagnosis about their sleep. Participants were asked to respond to a single item regarding the extent to which they were experiencing sleep disturbances. Fifty percent of the sample reported experiencing sleep problems ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ of the time. This preliminary finding underscores the need to fully characterize sleep disturbances in African-American breast cancer survivors by using a more comprehensive sleep assessment, as well as further examining factors associated with sleep in African-American breast cancer survivors.

Cognitive models have received growing attention in explaining the etiology of sleep disturbances in the general population [17]. Many people with sleep disturbances report that mental events contribute to their lack of sleep [17–20]. Such cognitive activity may include uncontrollable worry or intrusive thoughts about life situations that, over time, interrupt sleep patterns [17].

Intrusive distressing thoughts are a diagnostic feature of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [21, 22]. A diagnosis of breast cancer can be a life threatening experience and engender symptoms of PTSD including re-experiencing traumatic events (i.e. intrusive thoughts) and increased cognitive arousal known to interfere with normal sleep patterns [23]. It is therefore likely that intrusive thoughts about breast cancer are associated with complaints regarding sleep in breast cancer populations. A paucity of studies related to PTSD symptoms (i.e. intrusive thoughts) among breast cancer survivors include African-American survivors [23], and of this research, little data has been generated regarding the functional consequences of intrusive thoughts about breast cancer among African-Americans.

Fear of cancer recurrence may also contribute to cognitive arousal among cancer survivors and ultimately affect sleep patterns. The construct of fear associated with cancer recurrence is considered to involve intentional thoughts that can be ruminative and can be distinguished from intrusive thoughts, which are characterized as more automatic and unwanted thoughts. Fear of cancer recurrence has been associated with other aspects of functional well-being [24]. However, the relationship between fear of recurrence and sleep patterns has not been fully established. Determining the degree to which interference with sleep is related to thoughts of an intrusive nature versus other manifestations of recurrence fears could be of significance to clinicians.

Understanding the functional consequences of sleep impairments in African-American breast cancer survivors is also of importance. Fatigue is a potential behavioral consequence of sleep impairments in cancer survivors. For example, a recent study by Palesh et al. [25] showed that cancer survivors with sleep disorders had significantly more symptoms of fatigue than those without sleep impairments. However, fatigue can have multiple determinants in the context of a chronic illness.

Given the burden of breast cancer and sleep loss among African-American women, more work is needed that investigates the factors associated with sleep disturbance among African-American breast cancer survivors. The primary goals of this pilot study were (i) to report the prevalence and nature of sleep disturbance in a sample of African-American breast cancer survivors; (ii) to assess the extent to which intrusive thoughts about breast cancer and fear of recurrence contributes to sleep disturbances; and (iii) to assess the extent to which sleep disturbances contribute to fatigue.

Methods

Participants

To meet eligibility requirements, participants must (i) have been diagnosed with local or regional breast cancer; (ii) have not had a recurrence of breast cancer; (iii) have completed treatment (with the exception of Tamoxifen); (iv) have been at least 18 years of age or older; (v) have been African-American, Afro-Caribbean or African; and (vi) have been able to speak and read English.

Procedures

This study received approval from the Howard University Institutional Review Board. Research participants were identified from the Howard University Cancer Center registry. Letters were mailed to approximately 400 potential participants identified through the registry instructing the recipient to call the study center for more information about the study. In addition to direct mail, flyers were placed in the hospital cancer clinic describing the study. Members of the Cancer Center support group were also recruited.

All interested respondents were screened to determine current eligibility. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Eligible participants were either mailed a questionnaire or completed the questionnaire in the study center. Participants who were mailed a questionnaire were asked to mail the completed questionnaire back or bring it in to the study center.

Approximately 130 women responded to the study mailings and flyers. Twenty-six women were deemed ineligible because of having had a recurrence. Six women were not interested in participating, 16 women were scheduled but did not come to their scheduled appointment, and 31 women were not able to be recontacted by phone. A total of 51 participants were found to be eligible and completed the study requirements.

Instruments

Demographic characteristics were assessed via a questionnaire and included age, self-reported weight and height, education (high school, some college/vocational school, college degree, post-graduate degree), income (<$19,999, $20,000–$49,999, $50,000–$99,999, $100,000+), marital status (no partner, partner), surgery type (breast conserving surgery, mastectomy), time since diagnosis, stage of cancer at time of diagnosis, and treatment type (surgery only; surgery plus adjuvant therapy).

Difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep was assessed with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [26], a seven-item measure used to evaluate the perceived severity of clinically significant insomnia symptoms over the course of 2 weeks. Items from the ISI are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (anchors for scale include; 0 = not at all to 4 = very much), and a total score is obtained by summing the seven items, for a possible score ranging from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating greater insomnia severity. The ISI has been validated in patients with sleep disorders and cancer patients and has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of 0.65–0.78), reliability (test–retest r = 0.73–0.83) and convergent validity when compared with other sleep measures. For an oncology sample, scores >/=8 indicate clinically significant sleep difficulties associated with insomnia symptoms [27]. In the present study, total scale responses produced an overall alpha coefficient of 0.90.

Intrusive thoughts about breast cancer was measured using the Impact of Events Scale (IES) [28]. The IES is divided into two subscales: intrusion and avoidance. Only the intrusion subscale (IES-I; seven items) was used in the present study and it describes how thoughts and impressions related to the stressful event are experienced by the patient. Participants rate items on a six-point scale (0 = not at all to 5 = often) for how frequently, within the past 7 days were they bothered by thinking about issues related to breast cancer. Examples of intrusive thought questions are: ‘I thought about it when I didn't mean to.’…‘I had waves of strong feelings about it’. This measure has been used with a variety of populations including patients with breast cancer and has been demonstrated to be a valid and reliable measure. The nonweighted averages from 18 studies indicated that the intrusion subscale had good internal consistency with a coefficient of 0.86 [29]. In the present study, the intrusive thoughts subscale total demonstrated good internal consistency with an overall alpha coefficient of 0.87.

Fear of recurrence was measured with the Concerns of Recurrence Scale (CARS) [30]. The CARS systematically assesses the extent and the nature of women's concerns about breast cancer recurrence. It has two parts, with the first, measuring overall fear of cancer recurrence with four questions addressing frequency, potential for upset, consistency, and intensity of fears. Scores are given on a 6-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (not at all) to 6 (continuously) (range 1–6). Scores for the overall fear of recurrence scale were summed and averaged. The second part of the scale measures the nature of women's fears about recurrence and is assessed with 26 items subdivided into four domains: health worries (e.g. concerns about future treatment, physical health), womanhood worries (e.g. concerns about femininity, sexuality), role worries (e.g. concerns about responsibilities at work and at home, relationships with friends and family), and death worries (pertaining to the possibility that a recurrence of breast cancer could lead to death). The CARS subscale scores range from 0 to 4 on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), to indicate the extent to which they worry about each item. Scores for each subscale were summed and averaged yielding scores that range from 0–4. In the present study, total scale responses indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87 to 0.93).

Fatigue was measured using the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) [31]. The BFI was developed to assess the severity of fatigue and the amount of interference with function caused by fatigue. Three items in the BFI ask subjects to rate the fatigue experienced right now, the usual level of fatigue experienced during the past 24 hours, and the worst level of fatigue experienced during the past 24 hours (0 = nofatigue to 10 = fatigue as bad as you can imagine). Additional items assess how much fatigue has interfered with different aspects of the subject's life during the past 24 hours. The interference items are mood, normal work, relations with other people, and enjoyment of life. Each interference item is scored on an eleven-point rating scale (0 = does not interfere to 10 = completely interferes). A mean BFI score is calculated as the mean of the intensity and interference items. Scores for the BFI range from 0–10. The Cronbach's alpha reliability scores have ranged from 0.82 to 0.92 [31] and in the current study, the BFI demonstrated good internal consistency with an overall alpha coefficient of 0.92.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and percentages) were used to summarize participant characteristics (Table 1). The ISI was used to identify study participants with clinically significant sleep disturbance. As previously mentioned, an ISI score >/=8 distinguishes clinically significant sleep difficulties in oncology patients [27].

Table 1.

Demographic and treatment-related characteristics of study sample (N = 51)

| Variables | % |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.2 (12.3) years |

| range: 31–87 years | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 30.5 (6.2) kg/m2 |

| Marital status | |

| No partner | 62.7% |

| Partner | 37.3% |

| Educational attainment | |

| High school diploma | 13.7% |

| Some college/vocational school | 25.5% |

| College degree | 13.7% |

| Post-graduate degree | 47.1% |

| Income level | |

| Less than $19,999 | 11.8% |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 17.6% |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 47.1% |

| $100,00+ | 21.6% |

| Missing | 2.0% |

| Surgery type | |

| Breast conserving surgery | 43.1% |

| Mastectomy | 52.9% |

| Missing | 3.9% |

| Treatment type | |

| Surgery only | 9.8% |

| Surgery and adjuvant therapy | 88.2% |

| Missing | 2.0% |

| Stage of cancer at time of diagnosis | |

| 0 | 27.6% |

| 1 | 48.3% |

| 2 | 20.7% |

| 3 | 3.4% |

| Time since diagnosis, mean (SD) | 7.2 (4.3) years |

| range: 1–18 years |

Hierarchical linear regression models were performed to investigate the degree to which demographic, illness and treatment characteristics, intrusive thoughts (IES-I) and concerns of recurrence (CARS) account for the variance in insomnia symptom severity (ISI) and fatigue (BFI). Correlations among independent variables were calculated to identify potential predictor variables (see Table 2). Mean comparisons were utilized to identify significant differences in insomnia severity (ISI) and fatigue (BFI) ratings for categorical variables (e.g. marital status, educational attainment, income, stage of cancer at time of diagnosis, surgery type, treatment type) with significant differences observed for income and cancer stage at diagnosis for BFI ratings. The variables used in the insomnia symptom severity model included: IES-I, CARS: womanhood worries and CARS: role worries. The block function was utilized to include IES-I entered in Step 1, and CARS subscales were entered in subsequent steps. A similar procedure was used for the fatigue model with income, BMI, stage of cancer at diagnosis, and CARS: womanhood worries in Step 1 and ISI in Step 2. Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables

| Measure | ISI | BFI |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Body mass index | 0.19 | 0.42** |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | −0.26 | −0.09 |

| Intrusive thoughts (IES-I) | 0.35* | 0.22 |

| CARS: overall concern | 0.22 | 0.15 |

| CARS: health worries | 0.15 | −0.07 |

| CARS: womanhood worries | 0.34* | 0.30* |

| CARS: role worries | 0.31* | 0.11 |

| CARS: death worries | 0.06 | −0.15 |

| Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) | – | 0.42** |

| Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) | 0.42** | – |

CARS, Concerns of Recurrence Scale.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Results

Participant characteristics

As indicated in Table 1, the mean age of participants was 64.2 years (12.3). In addition, the majority of participants had above a high school education. Also, the average time since diagnosis was 7.2 years (4.3). All other participant characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Nature of insomnia

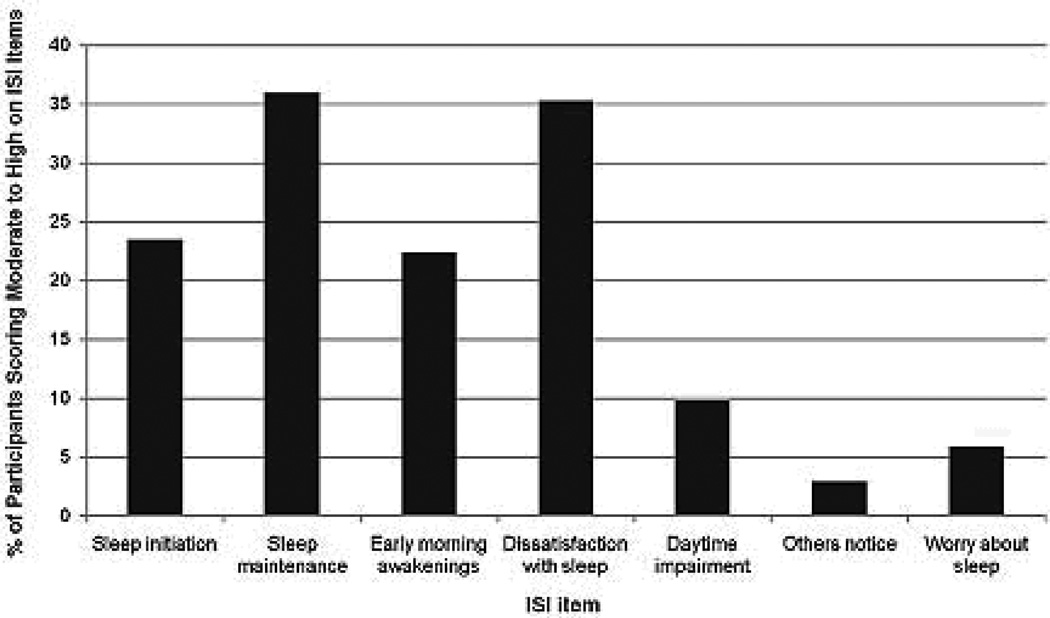

Clinically significant sleep disturbances were assessed with the ISI. As previously mentioned, using a cut off score of 8 for an oncology sample, clinically significant symptoms of insomnia were observed in 43.12% (n = 22) of study participants. Figure 1 represents the percentage of participants scoring moderate to high on ISI items. The most commonly identified sleep complaints in descending order of prevalence include: sleep maintenance (i.e. difficulty staying asleep) (36%), dissatisfied with sleep (35.3%), difficulty falling asleep (23.5%), and early morning awakenings (22.4%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants scoring moderate to high on Insomnia Severity Index Items

Predictors of insomnia

The next goal was to determine if intrusive thoughts about breast cancer and fear of recurrence were significant predictors of insomnia (ISI). Only intrusive thoughts accounted for significant variance in insomnia symptom severity (β = 0.35, p < 0.05) (Table 3) accounting for 12% of the variance in ISI scores. Concerns of cancer recurrence failed to add significantly beyond the contributions of intrusive thoughts.

Table 3.

Insomnia severity predicted by intrusive thoughts and concerns of cancer recurrence

| Variable | B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | – | – | – | 0.12* | – | 6.58* |

| Intrusive thoughts (IES-I) | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.35 | – | – | – |

| Step 2 | – | – | – | 0.17* | 0.05 | 4.76* |

| CARS: womanhood worries | 1.71 | 1.04 | 0.23 | – | – | – |

| Step 3 | – | – | – | 0.18* | 0.01 | 3.33* |

| CARS: role worries | 0.87 | 1.18 | 0.14 | – | – | – |

CARS, Concerns of Recurrence Scale.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Insomnia predicting fatigue

The final aim of this study was to determine if insomnia symptom severity was a significant predictor of fatigue (BFI). After controlling for demographic and disease characteristics, insomnia symptom severity significantly predicted fatigue (β = 0.32, p < 0.05) (Table 4) and accounted for 8% of the variance in BFI scores. Among the demographic and illness characteristics, only income and BMI contributed significantly to the model.

Table 4.

Fatigue predicted by sample demographics, disease characteristics, concerns of cancer recurrence, and insomnia symptom severity

| Variable | B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | – | – | – | 0.43*** | – | 4.69*** |

| Income | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.30* | – | – | – |

| Body mass index | −0.70 | 0.27 | −0.33* | – | – | – |

| Stage 1 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.09 | – | – | – |

| Stage 2 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.15 | – | – | – |

| Stage 3 | 2.28 | 1.17 | 0.30 | – | – | – |

| CARS: womanhood worries | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.12 | – | – | – |

| Step 2 | – | – | – | 0.51*** | 0.08* | 5.29*** |

| Insomnia Severity Index | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.32* | – | – | – |

CARS, Concerns of Recurrence Scale.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Discussion

This study adds to the limited body of research investigating sleep disturbances in African-American breast cancer survivors. The first goal of this study was to observe the extent and nature of sleep complaints in this population. Our results showed that a modest proportion of study participants reported clinically significant problems with sleep (43%). This finding is consistent with a comparative study by Malone et al. [32] in which 40% of cancer survivors reported sleep difficulties compared with only 15% of control participants with no severe illness. Most of the sleep-related difficulties reported by participants related to difficulty falling asleep and maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, and dissatisfaction with sleep. Similarly, Savard et al. [1] reported that in a group of breast cancer survivors with insomnia, 75% reported sleep onset insomnia, 86% complained of problems with sleep maintenance, and 73% reported awakening too early in the morning. Other less prominent concerns regarding sleep in the current study sample included insomnia induced interference with daily functioning, appearance of sleep problems to other people, and worries linked to sleep.

The next goal was to examine the extent to which intrusive thoughts about breast and fear of breast cancer recurrence contributed to sleep disorders in this group of African-American breast cancer survivors. Results indicated that intrusive thoughts about breast cancer predicted the severity of insomnia symptoms, accounting for 12% of the variance in ISI scores. The fact that intrusive thoughts contributed significantly to insomnia symptom severity is not surprising. Espie [17] attributed an underlying basis of insomnia to cognitive activity. Intrusive thoughts about life events may create a type of cognitive arousal that over time induces sleep problems. Intrusive thoughts as measured by the IES have been associated with less total sleep in adults [33]. Moreover, the emotional distress and anxiety that may result from these intrusive thoughts can eventually culminate into deficits in sleep and daytime functioning. Our results however, did not show worries associated with the fear of recurrence as significant predictors of insomnia symptom severity. This finding suggests that it may be more automatic, intrusive thoughts about breast cancer that interfere with sleep rather than specific concerns about breast cancer associated with womanhood and role worries.

The final goal of this pilot study was to determine if insomnia symptom severity significantly contributed to self-report fatigue ratings on the BFI in the study sample after accounting for covariates. Among the covariates included, only BMI and income contributed significantly to the model. Insomnia symptom severity significantly accounted for 8% of the variance in fatigue ratings improving overall model fit. This result was also not surprising given that fatigue is one of the most common complaints of cancer survivors with insomnia and has been reported to persist after treatment [34, 35].

The presence of sleep difficulties in this group of African-American breast cancer survivors further emphasizes the need to evaluate sleep disturbances in breast cancer survivors and to provide treatment when clinically indicated. Various methods of treatment have been proposed; however, cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) has been supported as an effective treatment. CBT integrates cognitive (cognitive restructuring) and behavioral (sleep education, stimulus control, relaxation, and sleep restriction) interventions to change a client's beliefs and attitudes about sleep and insomnia. Recent research has addressed the utility of addressing cognitions associated with intrusive thoughts through the use of cognitive therapy [18, 36, 37]. Cognitive behavioral therapy has also been utilized successfully to treat PTSD symptoms [38] and residual insomnia following PTSD treatment [39]. Given our findings regarding intrusive thoughts about breast cancer as a predictor of insomnia in this sample, these techniques could be promising adjuncts to standardized CBT interventions for insomnia in breast cancer survivors.

This study has several important strengths and limitations. First, the interpretation of study results and generalizability is somewhat limited because of the exploratory nature of this study and relatively small sample size. Second, because of the cross-sectional nature of data collection, statements about causal and directional relationships can only be inferred. Future research would be improved by adopting a longitudinal approach to examining factors impacting sleep disturbances and fatigue in breast cancer survivors. In addition, participants in this study were only screened for clinically significant symptoms of insomnia rather than being diagnosed with insomnia with an empirically supported assessment of sleep utilizing a structured clinical interview (e.g. Duke Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders) supplemented with daily sleep diary and actigraphy data and objective measures of sleep such as an overnight polysomnography assessment. These additional assessments would enhance the objectivity of sleep characteristics and rule out additional sleep disorders like obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder that can also cause sleep disturbances and fatigue.

Despite these limitations, this study has several important strengths. The ISI that was used as a measure of sleep was especially relevant to this study population. Savard et al. [27] empirically validated the ISI in a sample of cancer survivors and as a result, construct and divergent validity was established, as well as clinically significant cut-off scores to determine sleep disorders in cancer survivors. Future studies should expand this research by examining this question in other ethnic groups such as a Hispanic population, a group known to have significantly high breast cancer rates and sleep impairments [14, 40, 41].

Little is known about the functional well-being of African-American breast cancer survivors. This study, however, addressed this issue by exploring factors related to sleep disturbances in this population. The results from this study can be used to serve as the foundation for future ethnic comparisons, as well as for intervention studies that include diverse populations.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation: Population Specific Grants Program: POP0600475.

References

- 1.Savard J, Simard S, Blanchet J, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and risk factors for insomnia in the context of breast cancer. Sleep. 2001;24:583–590. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couzi RJ, Helzlsouer KJ, Fetting JH. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms among women with a history of breast cancer and attitudes toward estrogen replacement therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2737–2744. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.11.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindley C, Vasa S, Sawyer WT, et al. Quality of life and preferences for treatment following systemic adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1380–1387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Prevalence, burden, and treatment of insomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1417–1423. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen JC, Brunner RL, Ren H, et al. Sleep duration and risk of ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women. Stroke. 2008;39:3185–3192. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, et al. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien KL, Chen PC, Hsu HC, et al. Habitual sleep duration and insomnia and the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause death: report from a community-based cohort. Sleep. 2010;33:177–184. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanfranchi PA, Pennestri MH, Fradette L, et al. Nighttime blood pressure in normotensive subjects with chronic insomnia: implications for cardiovascular risk. Sleep. 2009;32:760–766. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.6.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips B, Mannino DM. Do insomnia complaints cause hypertension or cardiovascular disease? J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:489–494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayas NT, White DP, Al-Delaimy WK, et al. A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:380–384. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel SR, Malhotra A, White DP, et al. Association between reduced sleep and weight gain in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:947–954. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African-Americans 2009–2010. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale L, Do DP. Racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. Sleep. 2007;30:1096–1103. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redline S, Kirchner HL, Quan SF, et al. The effects of age sex, ethnicity, and sleep-disordered breathing on sleep architecture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:406–418. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall MH, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, et al. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: the SWAN sleep study. Sleep. 2009;32:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Northouse LL, Caffey M, Deichelbohrer L, et al. The quality of life of African American women with breast cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22:449–460. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(199912)22:6<449::aid-nur3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espie CA. Understanding insomnia through cognitive modelling. Sleep Med. 2007;8(Suppl 4):S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espie CA, Brooks DN, Lindsay WR. An evaluation of tailored psychological treatment of insomnia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1989;20:143–153. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(89)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey AG. Pre-sleep cognitive activity: a comparison of sleep-onset insomniacs and good sleepers. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;39(Pt 3):275–286. doi: 10.1348/014466500163284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichstein KL, Rosenthal TL. Insomniacs' perceptions of cognitive versus somatic determinants of sleep disturbance. J Abnorm Psychol. 1980;89:105–107. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.89.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. p. 943. xxxvii. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shipherd JC, Beck JG. The effects of suppressing trauma-related thoughts on women with rape-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green BL, Rowland JH, Krupnick JL, et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in women with breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:102–111. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Peters ML, de Rijke JM, et al. Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: a validation and prevalence study. Psycho Oncol. 2008;17:1137–1145. doi: 10.1002/pon.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, et al. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:292–298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savard MH, Savard J, Simard S, et al. Empirical validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in cancer patients. Psycho Oncol. 2005;14:429–441. doi: 10.1002/pon.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: psychometric properties. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:205–209. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vickberg SM. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women's fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:16–24. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malone M, Harris AL, Luscombe DK. Assessment of the impact of cancer on work, recreation, home management and sleep using a general health status measure. J R Soc Med. 1994;87:386–389. doi: 10.1177/014107689408700705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall M, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, et al. Intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors are associated with sleep disturbances in bereavement-related depression. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lichstein KL, Means MK, Noe SL, et al. Fatigue and sleep disorders. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:733–740. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smets EM, Visser MR, Willems-Groot AF, et al. Fatigue and radiotherapy: (B) experience in patients 9 months following treatment. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:907–912. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carney CE, Waters WF. Effects of a structured problem-solving procedure on pre-sleep cognitive arousal in college students with insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4:13–28. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvey AG, Bryant RA, Tarrier N. Cognitive behaviour therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:501–522. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3754–3761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeViva JC, Zayfert C, Pigeon WR, et al. Treatment of residual insomnia after CBT for PTSD: case studies. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:155–159. doi: 10.1002/jts.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009–2010. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Connor GT, Lind BK, Lee ET, et al. Variation in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing with race and ethnicity: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2003;26:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]