Abstract

PURPOSE

Efforts to better understand the impact of clinic member relationships on care quality in primary care clinics have been limited by the absence of a validated instrument to assess these relationships. The purpose of this study was to develop and validate a scale assessing relationships within primary care clinics.

METHODS

The Work Relationships Scale (WRS) was developed and administered as part of a survey of learning and relationships among 17 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care clinics. A Rasch partial-credit model and principal components analysis were used to evaluate item performance, select the final items for inclusion, and establish unidimensionality for the WRS. The WRS was then validated against semistructured clinic member interviews and VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) data.

RESULTS

Four hundred fifty-seven clinicians and staff completed the clinic survey, and 247 participated in semistructured interviews. WRS scores were significantly associated with clinic-level reporting for 2 SHEP variables: overall rating of personal doctor/nurse (r2 =0.43, P <.01) and overall rating of health care (r2= 0.25, P <.05). Interview data describing relationship characteristics were consistent with variability in WRS scores across low-scoring and high-scoring clinics.

CONCLUSIONS

The WRS shows promising validity as a measure assessing the quality of relationships in primary care settings; moreover, primary care clinics with lower WRS scores received poorer patient quality ratings for both individual clinicians and overall health care. Relationships play an important role in shaping care delivery and should be assessed as part of efforts to improve patient care within primary care settings.

Keywords: relationships, primary care, quality of care, patient satisfaction, Veteran’s Administration

INTRODUCTION

During the past several decades, primary care providers in the United States have faced increasing challenges, including rising health care costs and growing rates of chronic disease among patients that require escalating time and expertise to manage.1,2 A variety of strategies have been proposed to aid primary care providers, including redistributing the management of patients’ preventive and chronic illness care across interdisciplinary teams of physicians, physician assistants, and nurses—for example, as in the patient-centered medical home.3,4 Because communication and teamwork are critical to the success of such teams, achieving high-quality relationships among clinicians and staff is an essential component of improving primary care delivery.5,6

A number of researchers have proposed theoretical models of how high-quality relationships within primary care settings may contribute to improved quality of care. In a review of related research, Lanham et al7 identified 7 characteristics of work relationships in settings with high-quality practice outcomes: (1) trust, or feeling comfortable making oneself vulnerable to others; (2) mindfulness, or demonstrating openness to new ideas and multiple perspectives; (3) heedful interrelating, or individuals being attentive to how their roles and actions affect and intersect with those around them; (4) respectful interaction, or engaging in honest, confident, and appreciative relations between coworkers; (5) diversity, or having sufficient diversity to support creative problem solving; (6) social- and task-related communication; and (7) rich, or face-to-face, communication.

Lanham et al also proposed a model of how these relationship characteristics may influence practice outcomes by affecting how clinicians and staff engage in reflection and learning. Safran and colleagues suggest that these characteristics form the basis for organizational cycles of reflection and action through which a “culture of continual learning” is created.8(pS13) More recently, Miller et al have argued for the importance of these relationship characteristics in determining a practice’s adaptive reserve, ie, its effective resilience during periods of stress or change.9 Despite the value of such work, it has remained difficult to quantify the influence of primary care practice relationships on quality of care without a validated measure of relationships that allows for more direct comparison across sites.

The goal of the current study, therefore, was to develop a scale to assess staff and clinician relationships within primary care settings, and to conduct a preliminary validation of the scale using quantitative and qualitative methods. Because the current study was conducted in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care clinics, it also provided an opportunity to examine whether characteristics of relationship quality initially defined in non-VA settings remain meaningful in the VA, which has invested heavily in the effort to provide high-quality primary care in recent years.10,11 Little research has examined relationships within VA primary care settings, although successful implementation of clinical care practices in the VA context is thought to be at least partially dependent on work unit dynamics.12

Building on previous work in this area, we developed and validated a Work Relationships Scale (WRS) using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

METHODS

Study Design

We drew upon Lanham et al’s 7 characteristics to develop a set of 19 items assessing the perceived quality of work relationships7; in some cases items were developed in collaboration with other researchers working across multiple studies and adapted for use in the VA.13,14 All items were tested for face validity in a pilot project of 5 primary care clinics and refined based on insights gained. The resulting WRS was administered as part of a mixed methods survey of learning and relationships conducted among 17 VA primary care clinics in South and Central Texas. Questionnaires were distributed to all clinicians and staff of each clinic.

Information on patient experiences within these clinics was drawn from the Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP), an ongoing initiative of the VA’s Office of Quality and Performance.15 The SHEP collects regular input from a stratified random sample of VA patients who have received inpatient or outpatient care in the preceding month. We selected 4 SHEP variables from fiscal years 2010 to 2011 for the purpose of assessing overall clinic function and patient satisfaction during the study period. “Getting care quickly” assesses whether patients felt care was provided “as soon as you thought you needed” for urgent and regular care concerns in the previous 12 months; reported percentages reflect responses of either usually or always. “Overall rating of personal doctor/nurse” and “overall rating of health care” are scored from 0 to 10, where a rating of 0 indicates worst possible and 10 indicates best possible; reporting reflects the percentage of responses that endorse a rating of 9 or 10. “Clinician wait time” describes how long the patient waited before being seen; reporting reflects the percentage of responses indicating wait times of 20 minutes or less. Data for all variables were aggregated at the clinic level.

Study team members also observed clinic members interacting within each of the clinics for 3- to 5-day periods between January 2009 and September 2011. Key informants representing all clinic roles were selected based on these observations and asked to participate in semistructured individual interviews guided by open-ended questions regarding relationships within the clinic (Supplemental Appendix, available at www.annfammed.org/content/11/6/543/suppl/DC1).

All study procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and classical item analysis statistics were computed using procedures in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute). Rasch item analysis and principal components analyses were conducted. A partial-credit Rasch model was used to evaluate the original 19 items. The final subset of items to include in the scale were selected based on item-response convergence with respect to the underlying latent trait, the in-fit and out-fit statistics, and established ordinality of the responses. Unidimensionality was established by the Martin-Löf test and the results from a principal components analysis on the person-item residuals. SAS PROC Mixed was used to evaluate clinic differences in WRS scores. K-nearest neighbor analysis was used to impute missing data where 2 or fewer responses to the WRS were missing. Class statement was included to account for clustering of patient and respondent data within clinics. Spearman rank-order correlations between SHEP variables and mean WRS scores were used to assess the relationship between WRS relationship scores and patient perceptions of care quality.

As an additional means of assessing construct validity, we used mean clinic WRS scores to identify the 3 highest- and 3 lowest-scoring clinics and examined whether interview data revealed variation in clinic work relationships that was congruent with variability in scale findings.16 All interviews were transcribed and uploaded into the qualitative software program NVivo 8 (QSR International). We then conducted content analysis of all interview transcripts using a codebook developed by the research team and based upon Lanham et al’s 7 relationship characteristics. All members of the research team participated in coding, with at least 2 coders reviewing each transcript, and all transcripts were compared for agreement. For this analysis, we focused on clinic members’ descriptions of staff and clinician interactions and the presence or absence of Lanham et al’s relationship characteristics, noting how particular characteristics (eg, trust) clustered across responses from members of high- and low-scoring clinics. Case studies were prepared by the first author and then reviewed and refined by the rest of the research team.

RESULTS

Four hundred fifty-seven clinicians and staff from the 17 VA primary care clinics completed the clinic member questionnaires (overall response rate = 64.7%, range across clinics 29%–100%). Clinic member respondents were 70.2% male, with a mean age of 48.8 years (SD = 10.4), and represented all clinic roles: administrative officers (n = 13), front office staff (n = 72), medical directors (n = 14), physicians (n = 69), nurse practitioners and physician assistants (n = 12), and nursing staff (registered nurses and licensed vocational nurses; n = 169). Remaining individuals were from a range of specialized roles, such as dietician, psychologist, or social worker.

WRS Development: Item Evaluation

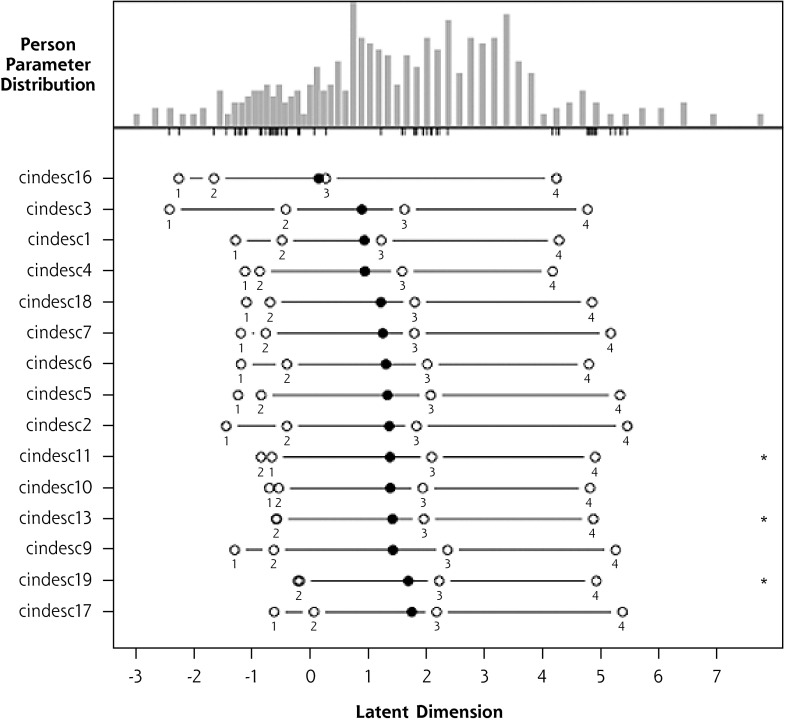

Using WRS responses to questionnaires collected as part of the clinic member survey, we fit a partial-credit Rasch model to item responses. Initial analysis of the degree of fit between scale items and the scale’s latent trait showed that 15 of the 19 original items had an in-fit and out-fit mean square ranging between 0.5–1.5, indicating they had good fit to the model and were productive for measurement (Supplemental Table, available at www.annfammed.org/content/11/6/543/suppl/DC1). The 4 items that fell outside this range were excluded. The original scale was coded on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree); however, inspection of the person-item map (Supplemental Figure 1, available at www.annfammed.org/content/11/6/543/suppl/DC1) showed disordered thresholds between the middle 2 categories (3 = slightly disagree and 4 = slightly agree) on a number of items. We therefore collapsed these categories to create a 5-point scale with a middle neutral response option. The likelihood ratio statistic for the Martin-Löf test supported the unidimensionality of the WRS. Principal component analysis on the person-item residuals showed little clear residual structure in the item responses. Item scores were summed to produce a total score ranging from 15 to 90. Higher scores suggest higher quality relationships. The 15-item WRS (Table 1) was found to have excellent internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .95), and inter-item correlations ranging from 0.29 to 0.80. Figure 1 displays the person-item map for the 15-item WRS.

Figure 1.

Person-item map for 15-item Work Relationships Scale.

Table 1.

Final Item-Fit Statistics for the Work Relationships Scale

| Item | χ2 | df | P Value | Out-fit Mean Square | In-fit Mean Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. This clinic encourages nursing staff (ie, RN, LVN, MA, CMA) input for making changes. | 459.6 | 353 | <.001 | 1.30 | 1.02 |

| 2. Most people in this clinic are willing to change how they do things in response to feedback from others. | 351.9 | 353 | .507 | 0.99 | 1.03 |

| 3. Most people in this clinic actively seek new ways to improve how we do things. | 335.3 | 353 | .743 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| 4. Most people in this clinic are comfortable voicing their opinion even though it may be unpopular. | 487.4 | 353 | <.001 | 1.38 | 1.33 |

| 5. Most people in this clinic pay attention to how their actions affect others in the clinic. | 376.5 | 353 | .186 | 1.06 | 1.10 |

| 6. After making a change, we usually discuss what worked and what didn’t. | 268.7 | 353 | >.999 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| 7. Most people in this clinic get together to talk about their work. | 339.8 | 353 | .684 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| 8. This clinic values people who have different points of view. | 327.7 | 353 | .829 | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| 9. Difficult problems in this clinic are usually solved through face-to-face discussion. | 303.7 | 353 | .973 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| 10. We regularly take time to consider ways to improve how we do things. | 367.8 | 353 | .283 | 1.04 | 0.84 |

| 11. When there is a conflict in this clinic, the people involved are encouraged to talk about it. | 249.0 | 353 | >.999 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| 12. Most people in this clinic understand how their job fits into the rest of the clinic. | 451.9 | 353 | <.001 | 1.28 | 1.34 |

| 13. This clinic usually encourages everybody’s input for making changes. | 250.7 | 353 | >.999 | 0.71 | 0.67 |

| 14. My opinion is valued by others in this clinic. | 271.3 | 353 | >.999 | 0.77 | 0.84 |

| 15. The leadership in this clinic usually makes sure that we have the time and space necessary to discuss changes to improve care. | 409.1 | 353 | .021 | 1.16 | 1.02 |

CMA = certified medical assistant; LVN = licensed vocational nurse; MA = medical assistant; RN = registered nurse.

Clinic Variation in WRS Scores

Clinic WRS scores are displayed in Table 2. Significant differences in WRS scores emerged between clinics (F value = 7.14, P <.0001). There was considerable variation in the number of patients enrolled in each clinic (mean = 7,630, range = 2,634–21,621) and the number of staff in each clinic (mean = 43.8, range = 17–92), but clinic WRS scores were not associated with either patient enrollment (r2 = −0.39, P = .12) or number of staff (r2 = −0.31, P =.22).

Table 2.

Work Relationships Scale Scores by Clinic

| Clinic | No.a | Mean Score (SD)b | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | 41 | 39.2 (11.0) | 19.0–58.0 |

| 2c | 44 | 41.7 (10.0) | 15.0–58.0 |

| 3c | 20 | 43.6 (12.4) | 19.0–61.0 |

| 4 | 13 | 44.3 (10.8) | 29.0–60.0 |

| 5 | 19 | 45.4 (11.7) | 28.0–71.0 |

| 6 | 19 | 46.2 (11.1) | 21.0–62.5 |

| 7 | 41 | 46.4 (12.1) | 20.0–75.0 |

| 8 | 10 | 48.7(11.6) | 31.0–66.0 |

| 9 | 32 | 50.8 (7.6) | 34.0–72.0 |

| 10 | 58 | 50.9 (11.6) | 18.0–75.0 |

| 11 | 32 | 51.3 (12.16) | 20.0–75.0 |

| 12 | 20 | 51.5 (10.0) | 28.5–65.0 |

| 13 | 36 | 51.9 (9.7) | 32.0–72.0 |

| 14 | 11 | 53.4 (11.6) | 27.0–72.0 |

| 15c | 25 | 57.1 (7.5) | 38.0–72.0 |

| 16c | 15 | 57.5 (4.2) | 51.0–68.0 |

| 17c | 9 | 60.1 (6.09) | 48.0–67.0 |

Number of respondents from each clinic.

Scored on a range from 15 to 90, with higher scores indicating higher quality relastionships.

Selected as representing high-scoring and low-scoring clinics.

WRS Scores and Patient-Assessed Quality

We also assessed patient satisfaction with clinic-level quality of care, using the SHEP variables “getting care quickly” (mean = 70.4, SD = 7.8), “overall rating of personal doctor/nurse” (mean = 50.1, SD = 7.8), “overall rating of health care” (mean = 63.2, SD = 8.4), and “clinician wait time” (mean = 69.8, SD = 11.8). Two variables were significantly associated with mean WRS score: “overall rating of personal doctor/nurse” (r2= 0.53, P <.05) and “overall rating of health care” (r2= 0.50, P <.05; Table 3). Relationships between mean WRS score and the 2 remaining variables—”getting care quickly” (r2= 0.19, P= .50) and “clinician wait time” (r2= 0.08, P= .78)—were not significant.

Table 3.

Survey of Health Care Experiences of Patients Variable Data for Participating Clinics, FY2010–2011, and Mean Work Relationships Scale Scores by Clinic

| Variable | Overall Rating of Health Care, r2 | Overall Rating of Doctor/Nurse, r2 | Getting Care Quickly, r2 | Clinician Wait Time, r2 | Mean Clinic WRS, r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall rating of health care | 1.00 | 0.81a | 0.28 | 0.55b | 0.50b |

| Overall rating of personal doctor/nurse | … | 1.00 | 0.71a | 0.45 | 0.53b |

| Getting care quickly | … | … | 1.00 | 0.24 | 0.19 |

| Clinician wait time | … | … | … | 1.00 | 0.08 |

SHEP = Survey of Health Care Experiences of Patients; WRS = Work Relationships Scale.

Note: Data are based on information for 17 clinics, with the exception of the variable getting care quickly (n=15), for which 2 clinics were missing from the FY2010–2011 SHEP data set.

P <.01, based on Spearman rank-order correlations.

P <.05, based on Spearman rank-order correlations.

Relationships in High- and Low-Scoring Clinics

Two hundred forty-seven clinic members representing all 17 clinics also participated in semistructured interviews. For this analysis, we examined all interviews from the 6 clinics that scored highest and lowest on the WRS. Five primary relationship characteristics emerged as consistently present in clinics with higher WRS scores: (1) rich or face-to-face communication, particularly during problem solving and conflict resolution; (2) heedful interrelating; (3) trust; (4) respectful interaction; and (5) mindfulness, particularly across clinic roles. In contrast, low-scoring clinics showed a marked lack of these characteristics. Table 4 provides quotes illustrating the presence or absence of these characteristics in high- and low-scoring clinics. Of the 2 remaining relationship characteristics, we found that diversity overlapped in this context with mindfulness and concluded that diversity did not improve our ability to characterize clinic-level relationship quality. We also found that clinic members across all clinics described using both social- and task-related communication. As comparable use of both types of communication was described across high- and low-scoring clinics, we determined that these communication styles may not function well as markers of relationship quality.

Table 4.

Quotes Related to Lanham et al’s Relationship Characteristics in Clinics with High and Low WRS Scores

| Rich communication | |

| Communication through face-to-face conversation; most effective when messages are unclear or ambiguous | |

| Low WRS score clinics | “I think that some days we should just sit down and say, ‘Okay, this is what’s going on. What do you know—how do you perceive this is supposed to be done?’ …[S]ometimes the hurdles that we run into are just, they could have been easily avoided if there had been a little bit better communication.” |

| High WRS score clinics | “Well, you know we have what’s called huddle every morning and any problems from the day before are discussed in huddle with all the team members and the clerical staff, social workers, the pharmacist. So we all get to know anything that’s going on at that time.” |

| Heedful interrelating | |

| Individuals are attentive to their work tasks and sensitive to how their roles and actions affect and intersect with those around them | |

| Low WRS score clinics | “…[T]here’s a whole lot of tension and a lot of it has to do with, ‘That ain’t my job and you’re messing in my area and you don’t belong in my area and you need to back out and just stay in your own business.’” |

| High WRS score clinics | “I think the teamwork here is just excellent. You know we really pitch in and try and help. Everyone’s attitude basically is that if one person’s working hard, we’re all working hard.” |

| Trust | |

| Individuals feel safe in making themselves vulnerable to others | |

| Low WRS score clinics | “Some people are probably not going to verbalize a lot, because they’re afraid it might get back to their boss or… because they don’t want to rock the boat.” |

| High WRS score clinics | “So, I have learned so much about medicine itself from these people; they’re wonderful…I’m not afraid to approach them for whatever the patient needs, because the goal is to provide the best and safest patient care.” |

| Respectful interaction | |

| Honest, appreciative, and self-confident interaction between individuals | |

| Low WRS score clinics | “That’s one of the things that kind of has me down on the clinic, just lack of communication, for coordination, lack of respect in my opinion, professionalism, and so, and your opinion about things, how things should run.” |

| High WRS score clinics | “The camaraderie among the team members, among the teams, among the different disciplines, that we work so cohesively together. So, ideal.” |

| Mindfulness | |

| Demonstrating openness to diverse ideas and perspectives | |

| Low WRS score clinics | “…I don’t even make suggestions anymore. I mean, you get tired after a while. I mean, you know, you really want to make a difference, but it doesn’t go anywhere and people get tired and frustrated….” |

| High WRS score clinics | “We have a really great chain of command that empowers us to make decisions and then also when we have problems to voice those concerns and tell them what our hurdles are and so they can help us on their end or help us with ideas about how to overcome the hurdles that we’re encountering.” |

WRS=Work Relationships Scale.

Note: Relationship characteristics from Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF, et al.7

Considerable differences emerged in patterns of communication and relating between low- and high-scoring clinics. Low-scoring clinics were more likely to make use of e-mail and other lean communication methods to transmit patient and clinic-related information. Clinicians and staff in these clinics often described good working relationships with those they work with most closely, such as those within their discipline (eg, other nurses) or those on their team (as in a physician-nurse pairing), while expressing reservations about relationships with individuals in more distant clinic roles or with upper management, which at times appeared to result in conflict and inefficiency. Clinicians and staff were less likely to feel comfortable raising potential concerns and sometimes felt as though workloads were not fairly distributed. Clinic members in low-scoring clinics often described feeling as though their concerns, when raised, went unheard and unaddressed.

High-scoring clinics, by contrast, tended to augment lean communication strategies with face-to-face communication to convey information, resolve conflict, and engage in problem solving. Those in high-scoring clinics described more heedful interrelating, with a strong sense of teamwork and shared purpose, as well as greater mutual helpfulness and task coordination among diverse clinic members. Trust and respectful interaction were more frequently observed in these clinics, where staff members described feeling comfortable asking questions and expressing opinions and were notably appreciative of the skills and hard work of their colleagues. Members of high-scoring clinics also described an environment in which concerns were heard and acknowledged, reflecting greater mindfulness.

DISCUSSION

We describe the development and initial validation of a scale to assess the quality of staff and clinician relationships within primary care clinics, moving toward the goal of supporting future research on the role of clinic member relationships in shaping quality of care. The triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data in this study provides insight into those characteristics associated with high- and low-quality relationships in primary care clinics and also provides the first description of such relationships in VA settings.

The 15-item Work Relationships Scale (WRS) was developed based on qualitative research examining relationships in high-functioning non-VA primary care clinics.8,17 Item content was based on 7 characteristics of work relationships identified in prior literature.7 Rasch analysis of the person-item responses and the principal components analysis on the person-item residuals show the WRS functions as a unidimensional measure of the overall quality of working relationships among team members in VA primary care clinics. This result, in turn, suggests that the characteristics of work relationships are tightly interrelated in these clinics. The WRS has excellent internal reliability and identified significant variation in relationship quality across the 17 primary care clinics examined in this study.

To assess whether the WRS was related to clinic-level patient outcomes, as would be predicted based on existing conceptual models, we also examined the association between mean WRS and patient experiences of care for each clinic. “Overall rating of health care,” which reflects patients’ perceptions of their care as a whole, and “overall rating of personal doctor/nurse,” which reflects patients’ perception of individual clinicians, were both significantly associated with WRS scores. In addition to providing evidence to support the convergent validity of the WRS, this finding also suggests that relationship quality within clinics may influence the patient’s experience of health care. Patients’ perceptions of health care are complex, and patients may not always be in a position to evaluate the technical competence of their care.18,19 Nonetheless, patients’ perceptions of health care are a valuable indicator of the quality of care delivery, offering insight into patient-clinician communication and the ability of clinicians to meet patients’ health care needs.20,21 These findings are consistent with conceptual models hypothesizing that relationship characteristics may have a downstream impact on practice outcomes7–9 and more broadly with the recognition that organizational factors, such as climate and culture, can affect care delivery.8,22 In describing the micro-relations within work units, relationship quality may make a unique contribution to understandings of organizational context, with relevance for quality improvement and the implementation of evidence-based practices.12 Further research in this area will be required.

Because both “getting care quickly” and “clinician wait time” require coordination of care across clinic clinicians and staff, and existing conceptual models predict that coordination of care should benefit from relationship quality, we also anticipated that mean clinic scores for each of these variables would be associated with clinic WRS scores. This did not prove to be the case. It may be that the ability to accommodate patient appointment needs and see patients in a timely fashion are affected by multiple factors—eg, the ratio of clinic staff to clinicians—that confound any impact of relationship quality in the current analysis.

Variability in WRS scores occurred in a predictable way alongside the presence (or absence) of relationship characteristics in the coded interview data. For example, clinicians and staff of high-scoring clinics were more likely than those of low-scoring clinics to describe viewing the clinic as a team and sharing tasks on a flexible basis. This heedfulness appeared to build morale and a sense of shared priorities among team members.

This study had a number of limitations, including a moderate response rate and relatively small sample of clinics from a single state. Nonetheless, both qualitative and quantitative data support the conclusion that the WRS has good construct and scale validity. Future research should examine the differential and predictive validity of the WRS and establish its ability to assess relationship quality in a variety of VA and non-VA clinical care settings.

This study is one of the first to show that relationships within a care organization affect patient satisfaction. Clinic member relationships appear to have a significant impact on patient perceptions of care and should be assessed as part of efforts to improve delivery.

Acknowledgments

Drs Benjamin Crabtree, Kurt Stange, Paul Nutting, William Miller, Reuben McDaniel, and Michelle Jordan contributed valuable work in developing the construct of work relationships in the primary care setting, and in developing some of the items from which the Work Relationships Scale items were adapted.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) project no. IIR 06-063. Dr. Finley is an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University, St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T. Primary care—will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(9):861–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Østbye T, Yarnall KSH, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Toole TP, Pirraglia PA, Dosa D, et al. Primary Care-Special Populations Treatment Team Building care systems to improve access for high-risk and vulnerable veteran populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(Suppl 2):683–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1): S33–S44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tresolini CP. Health Professions Education and Relationship-centered Care. San Francisco, CA: Pew-Fetzer Task Force; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. Complex responsive processes of relating. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S40–S44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. How improving practice relationships among clinicians and nonclinicians can improve quality in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(9):457–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safran DG, Miller WL, Beckman H. Organizational dimensions of relationship-centered care. Theory, evidence, and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S9–S15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Stange KC, Jaén CR. Primary care practice development: a relationship-centered approach. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S68–S79, S92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: Transformation of the veterans health care system. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:313–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yano EM, Simon BF, Lanto AB, Rubenstein LV. The evolution of changes in primary care delivery underlying the Veterans Health Administration’s quality transformation. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97(12):2151–2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukas CV, Mohr DC, Meterko M. Team effectiveness and organizational context in the implementation of a clinical innovation. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(1):25–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaén CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S57–S67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohman-Strickland PA, John Orzano A, Nutting PA, et al. Measuring organizational attributes of primary care practices: development of a new instrument. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3 Pt 1):1257–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnett-Zeigler I, Zivin K, Ilgen MA, Islam K, Bohnert AS. Perceptions of quality of health care among veterans with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(9):1054–1059 Correction: Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(4):310. (Note: Islam, Khairul [added]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14(4):532–550 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tallia AF, Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF. 7 characteristics of successful work relationships. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13(1):47–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim PC, Tang NKH, Jackson PM. An innovative framework for health care performance measurement. Manag Serv Qual. 1999;9(6):423–433 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinagre MH, Neves J. The influence of service quality and patients’ emotions on satisfaction. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2008;21(1): 87–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howard M, Brazil K, Akhtar-Danesh N, Agarwal G. Self-reported teamwork in family health team practices in Ontario: organizational and cultural predictors of team climate. Can Fam Physician. 2011; 57(5):e185–e191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]