Abstract

Purpose

Integration of palliative care into oncology practice remains suboptimal. Misperceptions about the meaning of palliative care may negatively impact utilization. We assessed whether the term and/or the description of palliative care services affected patient views.

Methods

2×2 between-subject randomized factorial telephone survey of 169 patients with advanced cancer. Patients were randomized into 1 of 4 groups that differed by name (supportive care vs. palliative care) and description (patient-centered vs. traditional). Main outcomes (0–10 Likert scale) were patient understanding, impressions, perceived need, and intended use of services.

Results

When compared to palliative care, the term supportive care was associated with better understanding (7.7 vs. 6.8; p=0.021), more favorable impressions (8.4 vs. 7.3; p=0.002), and higher future perceived need (8.6 vs. 7.7; p=0.017). There was no difference in outcomes between traditional and patient-centered descriptions. In adjusted linear regression models, the term supportive care remained associated with more favorable impressions (p=0.003) and higher future perceived need (p=0.022) when compared to palliative care.

Conclusions

Patients with advanced cancer view the name supportive care more favorably than palliative care. Future efforts to integrate principles of palliative medicine into oncology may require changing impressions of palliative care or substituting the term supportive care.

Keywords: Palliative Care, Supportive Care, Advanced Cancer, Communication, Oncology

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care services play an integral role in the multidisciplinary care of patients with advanced cancer and their families [1]. Specialized palliative care provided concurrently with standard oncology care decreases burdensome psychological symptoms, improves quality of life, decreases healthcare costs near death, optimizes timing of therapies, and may prolong life [2–9]. Support for integrating palliative care services into standard oncology practice is growing. International organizations including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the European Society for Medical Oncology, the Institute of Medicine, and the World Health Organization are calling for a new paradigm of advanced cancer care that incorporates the principles and practice of palliative medicine [10–14]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recently published a provisional clinical opinion stating that “combined standard oncology care and palliative care should be considered early in the course of illness for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden.”[15

To date, however, the provision of palliative care services to patients with advanced cancer remains suboptimal. Informational, emotional, and physical needs are frequently unmet among patients with incurable disease receiving standard oncology care [16–18]. The majority of specialized palliative care services are provided in the hospital, when patients are sicker, families are under stress, and decision-making about goals of care is difficult [19–21].

One reason for inadequate use of palliative care may be misperceptions about the meaning and/or scope of palliative care services. Patients and providers may mistakenly equate palliative care with hospice or assume that palliative care services cannot be provided concomitantly with active treatment [22, 23]. The term palliative care may act as a barrier to early patient referrals because it is viewed as distressing by oncologists, who may be more likely to refer patients to a service called supportive care [24–27]. Whether patients hold similar views, however, is not known. A recently conducted consumer marketing survey suggests that a new description of palliative care may positively affect the public’s impressions of these services [28]. However, this issue has never been formally tested in patients with cancer who, because of their experience, may have very different attitudes toward palliative care. To date, there has been no systematic assessment of how the term supportive care (versus palliative care) or the description of services affect the understanding and views of oncology patients.

METHODS

Design Overview

We conducted a randomized, between-subject, 2×2 factorial telephone survey of patients with advanced cancer to assess the impact of language used to describe outpatient palliative care services on patient understanding, impressions, perceived need, and intended use. Patients were randomized into 1 of 4 groups that differed by terminology (supportive care vs. palliative care) and description (patient-centered vs. traditional). This study did not require clinical trial registration because there was no intervention affecting health outcomes. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Subjects and Setting

From December, 2011 to April, 2012, we recruited patients from 20 participating medical oncologists practicing at 2 university-affiliated cancer treatment centers with outpatient palliative care clinics (referred to as the Cancer Pain and Supportive Care Clinic and the Palliative Care Outpatient Clinic) in Pittsburgh, PA. One additional medical oncologist was approached but declined to participate because he did not want the term palliative care used with his patients. Eligible patients were adults with advanced solid tumors, defined as stage IV, or refractory or recurrent hematologic malignancies. We included patients who had an appointment with their oncologist within the past 3 months or in the next 1 month, had a working telephone number, and were able to complete a 30-minute interview without assistance. We excluded patients who were determined by their oncologist to be emotionally or physically unable to participate in a thirty-minute telephone interview.

Survey Content

Language. Surveys used either the term palliative care or supportive care throughout [26]. The traditional description of these services used language from participating cancer center websites that is also found in many published descriptions of palliative care [28–30]. The patient-centered description used language that was preferred by the general public in a national consumer survey conducted by the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the American Cancer Society [28]. See Textbox 1 for complete descriptions.

Outcome Measures. All outcomes were measured on a 0 through 10 Likert scale. We assessed perceived understanding by asking patients to rate their overall understanding of what palliative (or supportive) care services offer (0—do not understand at all to 10— completely understand). Similar to the Center to Advance Palliative Care/American Cancer Society survey, we measured impressions by asking patients to rate how favorable their overall impressions of palliative (or supportive) care services were (0—not at all favorable to 10—most favorable). We assessed perceived need and intended use by asking patients how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following statements (0—strongly disagree to 10—strongly agree): “Palliative (or supportive) care services would be helpful to me or my family now” (current perceived need); “Palliative (or supportive) care services would be helpful to me or my family in the future” (future perceived need); “I am likely to ask my oncologist if I can see a palliative (or supportive) care doctor” (patient-initiated intended use); and “I would be willing to see a specialized palliative (or supportive) care doctor if my oncologist recommended it” (oncologist-initiated intended use).

Open-ended responses. Prior to describing palliative/supportive care to patients, we asked patients to describe in their own words what they thought palliative (or supportive) care was.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics. Age, gender and cancer diagnosis were abstracted from the medical record. The survey included questions about patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and prior experience with palliative/supportive care.

Textbox 1.

Traditional and Patient-Centered Descriptions of Palliative/Supportive Care

| Traditional |

| Palliative care (or supportive care) is specialized medical care for patients with lifelimiting illness. This type of care is focused on the management of symptoms such as pain, nausea, anxiety and stress for patients with advanced cancer. The goal is to improve patient’s quality of life. Emphasis is placed on communication and coordinated care with the patient’s cancer doctors. Palliative care (or supportive care) is appropriate from the time of diagnosis with a life-limiting illness and can be provided together with other cancer treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation. |

| Patient-Centered |

| Palliative care (or supportive care) is specialized medical care for people with serious illness. This type of care is focused on providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness – whatever the diagnosis. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family. Palliative care (or supportive care) is provided by a team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work with a patient’s cancer doctors to provide an extra layer of support. Palliative care (or supportive care) is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness, and can be provided together with curative treatment. |

All survey questions were pilot-tested for clarity and ease of administration over the phone prior to use. The complete survey is included as an appendix.

Enrollment

Participating medical oncologists identified up to 30 patients each (range 6 to 30) who met eligibility criteria and had an appointment in the past 3 months or upcoming 1 month by reviewing their clinic schedules from this specified time frame. We mailed eligible patients an explanation of the study that included an interview guide to visualize responses and a toll-free opt out phone number. Two interviewers (RM and LB) trained in telephone interview techniques contacted patients by phone within three weeks of mailing the informational letter and up to a maximum of 5 times each. Interviews were conducted by phone either immediately after verbal consent or during a subsequent telephone call scheduled at a convenient time. All participants provided verbal consent.

Randomization

We used computer-generated block randomization stratified by age (>65 or </= 65 years of age), sex, and interviewer to ensure equal distribution of subjects into 1 of 4 groups: 1) palliative care/patient-centered description, 2) palliative care/traditional description, 3) supportive care/patient-centered description, and 4) supportive care/traditional description. Patients were randomized immediately following verbal consent and before beginning the interview.

Power Calculation

We estimated that a sample size of 152 participants (38 per group) would yield 85% power (2-sided α = 0.05) to detect a difference of 1 point in our main outcome measures [28]. We anticipated a 50% enrollment rate based on prior experience with patient telephone surveys and aimed to identify 304 eligible participants.

Analysis

We generated descriptive statistics of patient demographic and clinical characteristics. We used mean (standard deviation) to describe normally distributed continuous variables and median (median absolute deviation) to describe continuous variables with a skewed distribution. We used ANOVA F tests, Kruskal Wallis tests, and chi-squared test to compare demographic and clinical variables by randomized groups. We used two-way AVOVA to test for interaction between the factors (term and description) and to compare mean outcome measures by the 2 factors (term and description). We conducted a series of univariate regression models to determine which individual covariates were associated with each outcome. Terminology (supportive care vs. palliative care), description (patient-centered vs. traditional) and additional variables with a p-value < 0.1 in univariate analyses were included in final multivariate regression models.

We used qualitative description to analyze narrative responses [31]. Three investigators (RM, LB and YS) used constant comparative methods to develop a coding framework [32, 33]. All disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus. The codebook was then applied to all responses by a single investigator (LB) who was blinded to randomization group. After coding was completed, we used chi-squared tests to compare response categories by randomization group (palliative care vs. supportive care).

All analyses were conducted in R. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2011).

RESULTS

Enrollment and Randomization

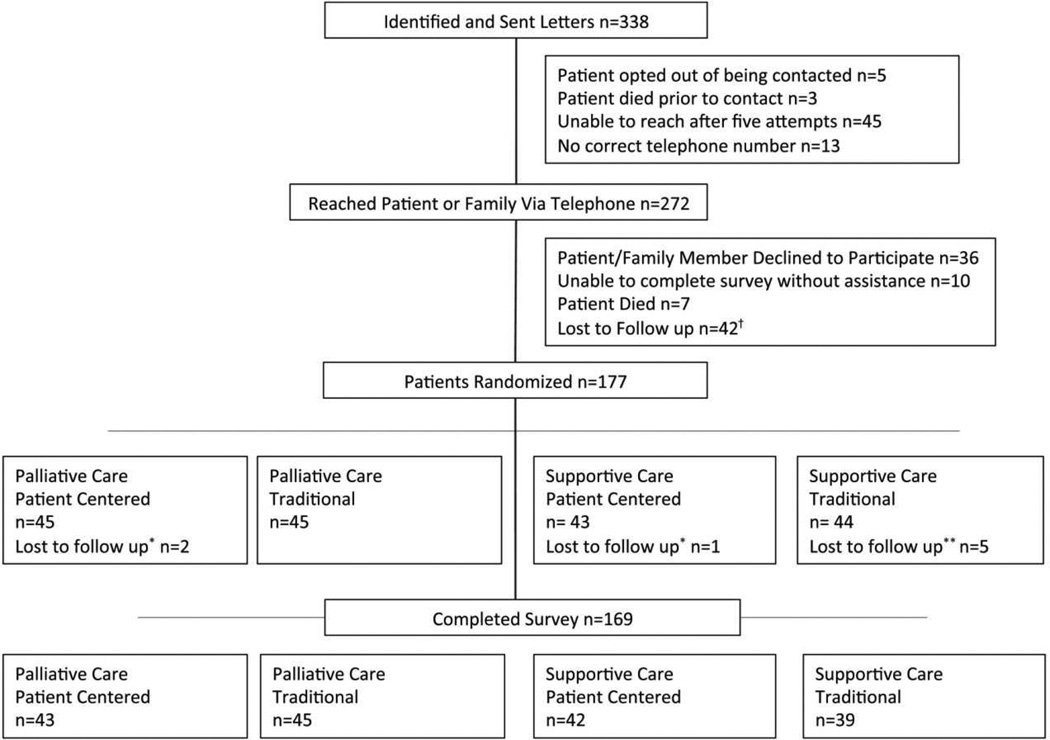

Patient enrollment is summarized in Figure 1. Of the 338 subjects identified as eligible, 272 patients or family members were reached by telephone, 177 patients were randomized, and 169 completed the survey.

Figure 1. Consort diagram detailing patient flow through the study including recruitment, randomization, and completion.

†Patients were reached, requested call back, and were unable to reach on subsequent attempts

*Patients were reached, requested call back after randomization, and were unable to reach on subsequent attempts

**After randomization, patient was not reached during scheduled interview (n=1), patient died (n=1), was determined to be unable to complete without assistance (n=2), and interviewer deviated from standard script and decision was made not to be in final analysis (n=1)

Patient Characteristics

There were no significant differences in age (p=0.199), gender (p=0.127), or cancer diagnosis (p=0.1) between participants and non-participants. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The most common cancer diagnoses were breast (54/169, 32%) and lung (31/169, 18%). Eleven percent of patients (18/169) reported they had seen a specialized palliative/supportive care provider in the past. There were no significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between randomization groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Overall and By Randomized Group*

| Participant Characteristics |

All Participants N=169 |

Palliative Care, Patient Centered N=43 |

Palliative Care, Traditional N=45 |

Supportive Care, Patient Centered N=42 |

Supportive Care, Traditional N=39 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 62.3 (11.6) | 62.3 (10.1) | 63.1 (9.2) | 60.7 (13.6) | 62.9 (13.4) | 0.78 |

| Female | 107 (63.3) | 27 (62.8) | 28 (62.2) | 27 (64.3) | 25 (64.1) | 0.9966 |

| Race | 0.251 | |||||

| Caucasian | 161 (95.3) | 39 (90.7) | 43 (95.6) | 42 (100.0) | 37 (94.9) | |

| Education | 0.998 | |||||

| ≤ High School | ||||||

| Diploma/GED | 50 (29.6) | 12 (27.9) | 13 (28.9) | 16 (38.1) | 9 (23.1) | |

| > High School | ||||||

| Diploma/GED | 119 (70.4) | 31 (72.1) | 32 (71.1) | 26 (61.9) | 30 (76.9) | |

| Average Household Income | 0.875 | |||||

| < $30,000 | 33 (19.5) | 9 (20.9) | 10 (22.2) | 8 (19.1) | 6 (15.4) | |

| ≥ $30,000 | 97 (57.4) | 22 (51.2) | 27 (60.0) | 25 (59.5) | 23 (59.0) | |

| Declined to answer | 39 (23.1) | 12(27.9) | 8 (17.8) | 9 (21.4) | 10 (25.6) | |

| Religion | 0.545 | |||||

| Catholic/Christian | 150 (88.8) | 39 (90.7) | 42 (93.4) | 38 (90.5) | 31 (79.5) | |

| Jewish | 7 (4.1) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Other religion | 6 (3.6) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.7) | |

| Non/agnostic | 5 (3.0) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Importance of Religion | 0.851 | |||||

| Very Important | 125 (74.0) | 32 (74.4) | 35 (77.8) | 31 (73.8) | 27 (69.2) | |

| Somewhat Important | 31 (18.3) | 6 (14.0) | 8 (17.8) | 8 (19.0) | 9 (23.1) | |

| Not Important | 13 (7.7) | 5 (11.6) | 2 (4.4) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.7) | |

| Self-Reported Quality of Life | 0.490 | |||||

| Excellent | 26 (15.4) | 6 (14.0) | 6 (13.3) | 8 (19.0) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Very Good | 58 (34.3) | 15 (34.9) | 17 (37.8) | 17 (40.5) | 9 (23.1) | |

| Good | 56 (33.1) | 16 (37.2) | 15 (33.3) | 12 (28.6) | 13 (33.3) | |

| Fair | 21 (12.4) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.1) | 3 (7.1) | 10 (25.6) | |

| Poor | 8 (4.7) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Seen Palliative/Supportive | 0.132 | |||||

| Care Provider | 18(10.7) | 2 (4.7) | 7 (15.6) | 7 (16.7) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Cancer Diagnosis | 0.860 | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | 22 (13.0) | 4 (9.3) | 4 (11.9) | 5 (11.9) | 9 (23.1) | |

| Genitourinary | 18 (10.7) | 4 (9.5) | 7 (15.5) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Gynecologic | 2 (1.2) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Brain | 2 (1.2) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Breast | 54 (32) | 13 (30.9) | 13 (28.9) | 16 (38.1) | 12 (30.8) | |

| Hematologic | 19 (11.2) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (11.1) | 6 (14.3) | 3 (7.7) | |

| Lung | 31 (18.3) | 7 (16.7) | 7 (15.6) | 8 (19.0) | 9 (23.1) | |

| Sarcoma | 12 (7.1) | 6 (14.3) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Skin | 7 (4.7) | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Other | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

Months Since Cancer Diagnosis, Median (MAD)** |

46 (54.9) | 30 (32.6) | 46 (54.9) | 52 (63.8) | 52 (47.4) | 0.164 |

|

Months Receiving Oncologist’s Care, Median (MAD)** |

24 (27.4) | 20 (20.8) | 17 (22.2) | 36 (40.0) | 24 (26.7) | 0.551 |

All numbers are reported as N (%) except where indicated otherwise.

P-values calculated with Kruskal Wallis test due to skewed data. All others were calculated with ANOVA F test or Chi-squared tests. MAD indicates Median Absolute Deviation

Main Outcomes

Main outcomes by randomization group are summarized in Table 2. There were no significant interactions between term (supportive care vs. palliative care) and description (patient-centered vs. traditional). The term supportive care (versus palliative care) was associated with better understanding (7.7 vs. 6.8; p=0.021), more favorable impressions (8.4 vs. 7.3; p=0.002), and higher future perceived need of services (8.6 vs. 7.7; p=0.017), but not with higher current perceived need (5.0 vs. 4.7; p=0.548) or intended use (self-initiated, 6.3 vs. 5.8; p=0.372; oncologist-initiated, 8.8 vs. 8.4; p=0.177). Outcomes did not differ by description (patient-centered vs. traditional) of palliative/supportive care services.

Table 2.

Understanding, Impressions, Perceived Need, and Intended Use of Palliative Care Services Overall and by Randomized Group*

| All Subjects (N=169) |

Palliative Care, Patient- Centered (N=43) |

Palliative Care, Traditional (N=45) |

Supportive Care, Patient- Centered (N=42) |

Supportive Care, Traditional (N=39) |

Supportive vs. Palliative p-value |

Patient- Centered vs. Traditional p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding | 7.3 (2.6) | 6.7 (3.0) | 7.0 (2.6) | 7.7 (2.2) | 7.8 (2.2) | 0.027 | 0.660 |

| Impressions | 7.8 (2.4) | 7.0 (3.0) | 7.5 (2.2) | 8.5 (2.0) | 8.3 (2.1) | 0.002 | 0.636 |

| Current Perceived Need | 4.9 (3.3) | 4.1 (3.3) | 5.3 (3.3) | 5.0 (3.4) | 5.1 (3.2) | 0.547 | 0.194 |

| Future Perceived Need | 8.1 (2.3) | 7.5 (2.7) | 8.0 (2.3) | 8.7 (1.9) | 8.5 (1.9) | 0.018 | 0.601 |

| Self-initiated Intended Use |

6.0 (3.5) | 5.4 (3.6) | 6.1 (3.8) | 6.3 (3.5) | 6.2 (3.1) | 0.375 | 0.638 |

| Oncologist-initiated Intended Use |

8.6 (2.0) | 8.3 (2.0) | 8.4 (2.2) | 8.9 (2.0) | 8.7 (1.7) | 0.179 | 0.746 |

All numbers are reported as mean (SD)

Univariate regression results are included in the appendix. In final multivariate models adjusted for term (supportive care vs. palliative care), description (patient-centered vs. traditional), and all significant variables (p<0.1) in univariate analyses, the term supportive care (vs. palliative care) remained associated with more favorable impressions (p=0.003) and higher future perceived need (p=0.022) of services. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Understanding, Impressions, Perceived Need, and Intended Use of Palliative Care Services *

| Overall Understanding |

Impressions | Current Perceived Need |

Future - Perceived Need |

Self -Initiated Intended Use |

Oncologist Initiated Intended Use |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | −0.605 (0.202) | −0.585 (0.174) | - | - | - | - |

| Race, White | - | −0.122 (0.899) | - | - | - | - |

| Education, some college education or college degree | - | - | - | 0.466 (0.311) | - | - |

| Income, > $30,000 annually | 1.637 (0.001) | 1.190 (0.012) | - | 0.617 (0.198) | - | - |

| Christian Religion | −1.092 (0.095) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Quality of Life | - | - | −0.381 (0.118) | |||

| Seen Palliative / Supportive Care Provider | - | - | 2.22 (0.007) | - | 2.332 (0.009) | - |

| Cancer Diagnosis** | 0.886 (0.077) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Months Since Cancer Diagnosis | 0.001 (0.740) | 0.003 (0.346) | −0.004 (0.310) | - | - | - |

| Months Receiving Oncologist’s Care | - | - | −0.007 (0.331) | - | - | - |

| Supportive vs. Palliative Care Terminology | 0.644 (0.124) | 1.247 (0.003) | 0.403 (0.426) | 0.934 (0.022) | 0.449 (0.403) | 0.415 (0.183) |

| Patient-Centered vs. Traditional Description | 0.150 (0.717) | 0.163 (0.684) | 0.609 (0.232) | 0.208 (0.604) | 0.231 (0.667) | −0.100 (0.746) |

All values presented as Correlation Coefficient (p-value). All analyses adjusted for Supportive Care vs. Palliative Care Terminology, Patient Centered vs. Traditional Descriptions, and additional variables that were significant (p<0.1) in univariate analysis.

Dichotomized as Breast Cancer vs. All Other Types Cancer.

Qualitative Results

Patient responses to the question “can you please describe in your own words what you think palliative care (or supportive care) is?” are presented in Table 4. A higher percentage of patients expressed confusion about what palliative care meant as compared to what supportive care meant (p=<0.001). Patients were more likely to describe supportive care as involving psychological, mental, or social support (p=<0.001) or opportunities for medical communication/information exchange (p=0.001) and more likely to describe palliative care as end-of-life care (p=0.006).

Table 4.

Patient’s Responses to the Question “Can you please describe in your own words what you think palliative care/supportive care is?”

| Patient Response Themes | All Patients (N=169)* |

Palliative Care (N=88) |

Supportive Care (N=81) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Don’t Know | 46 | 45 | 1 | <0.001 |

| “I have no idea.” | ||||

| “I’m not sure.” | ||||

| Psychological/Mental/Social Support | 42 | 2 | 40 | <0.001 |

| “I think it is care that would provide mental health services if you’re stressed, like support groups.” | ||||

| “To help me get through bad times and to understand that people go through the same things. To help, to talk, to get through bad stuff, having family members and friends and doctors.” | ||||

| Symptom/Additional Medical Care | 45 | 27 | 18 | 0.285 |

| “Care that is designed to keep you as pain free as possible and as well as possible.” | ||||

| “Healthcare not directly related to cancer but to other side issues with medications and nutritional stuff.” | ||||

| Medical Communication/Information Exchange | 17 | 2 | 15 | 0.001 |

| “Its follow ups and you’re able to speak to a nurse to answer general questions.” | ||||

| “I imagine they would help you if you have any questions.” | ||||

| End-of-Life Care | 13 | 12 | 1 | 0.006 |

| “When people are at the end of their life, like hospice care, that kind of thing.” | ||||

| “I think that I have always assumed that it was end-stage medical care.” | ||||

| Activities of Daily Living/Financial/Home Support | 13 | 4 | 9 | 0.190 |

| “Assistance with living at home.” | ||||

| “Its when they help you with your medicine and things. They help pay for it. People come in and take care of you.” | ||||

| Unspecified Additional Care/Support | 16 | 5 | 11 | 0.137 |

| “I don’t know, care to help me I think it would be.” | ||||

| “Somebody to help you out whenever you have problems.” | ||||

Numbers total to more than 169. One patient response included 3 themes, 21 included 2 themes, and 147 included 1 theme.

P-values computed with Chi-squared Test.

DISCUSSION

In a randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services, patients with advanced cancer reported more favorable impressions and higher future perceived need for supportive care (versus palliative care). To our knowledge, this study is the first systematic comparison of attitudes toward the term palliative versus supportive care among patients with cancer. Patients were more likely to interpret supportive care as a service that provides medical communication and information as well as psychological, mental, and social support, whereas they were more likely to equate palliative care with end-of-life services.

Our findings raise concerns as to how patients perceive the term palliative care. Unfamiliarity and/or negative associations with the term palliative care may result in less favorable impressions and lower perceived need for these services. The reasons underlying these more negative perceptions are not entirely clear. In our study, over half of the patients did not know what palliative care meant. This finding builds on prior research demonstrating a lack of familiarity with the term among oncology nurses [23] and the general public [28], as well as among patients with cancer [22]. Palliative care also lacks a standard definition in the supportive and palliative oncology literature [29, 34]. In the absence of a clear understanding of what palliative care means, patients may invoke prior experiences of palliative care with friends or loved ones. The fact that most patients receive palliative care late in their disease course [19, 20] may play into perceptions that this service is for patients at the end of life, leading to a lower perceived need for palliative care among patients who are not at this stage. Patients may develop a misunderstanding about palliative care from their oncologists, who often think of it as end-of life care [25]. Finally, the fact that palliative care is so closely tied to hospice - for example in the United States, the subspecialty board certification is for Hospice and Palliative Medicine - may contribute to this view. Hospice care has been available for a longer period of time and continues to be a more familiar concept [22, 28]. Patients who are not eligible for hospice may not think of palliative care as an option.

While we had hypothesized that using recently developed patient-centered language to describe palliative/supportive care services may improve understanding, impressions, perceived need, and intended use, we found no such association between descriptions and these outcomes [28]. Our findings differ from the national marketing survey sponsored by the American Cancer Society and the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in which the public rated newer, patient-centered language more positively [28]. This finding may result from the fact that our study involved patients with advanced cancer who likely have greater familiarity with these services than the general public. In addition, our study also utilized a more stringent randomized design than the marketing survey, which may also account for our different results. Patients reported being more willing to seek palliative/supportive care services when recommended by their oncologist. This finding highlights the importance of trust between patients and oncologists in the setting of life-threatening illness, which may lead to a hesitancy to question oncologists’ advice or independently engage with additional providers. While referral from an oncologist is not required for a palliative care clinic visit at many cancer centers and efforts have been made to increase patient-driven requests for palliative care [10], improved integration of palliative care services will require the active participation and support of oncologists.

These findings have practical implications. Lack of patient familiarity with the term palliative care creates an opportunity for palliative care clinicians to define palliative care services for patients, particularly in outpatient oncology settings where subspecialty palliative care clinics are growing rapidly and have many unique features from hospital and hospice-based palliative care programs. However, the fact that patients were most likely to associate the true scope of outpatient palliative care services with the term supportive care suggests that substituting this term may decrease barriers to service use. Recognizing that many patients equate palliative care with death and dying, oncologists may also choose to substitute the term supportive care and/or directly elicit and address patient concerns when recommending these services [24–26, 35–37]. Of note, addressing barriers to service use should not be confused with changing the nature of services provided. It is possible that any name applied to palliative care services will eventually be associated with end-of-life care. [38] Additional work is needed to ensure that descriptions of palliative care in research and clinical settings are clear and reflect evolving definitions of the field [39].

Our study has several limitations. First, just over half of identified patients completed the study. However, our enrollment rate compares favorably to other published telephone surveys and there were not significant demographic differences between participants and non-participants [40, 41]. Second, the majority of respondents were Caucasian. Previous research suggests that awareness of palliative care may be even lower among more racially/ethnically diverse groups [22]. Third, we conducted this study at two cancer centers with well-established palliative care programs. Our findings may not generalize to other centers with less-established palliative care services. Fourth, the name of outpatient palliative care clinics at these cancer centers may have influenced participant responses, though a minority of participants had used these services. Finally, because we were not able to directly measure service use it is not clear to what extent these findings will translate into clinically meaningful differences.

In summary, it is important to consider how patients perceive the terms palliative versus supportive care, as language may significantly affect understanding, impressions, and use. Providing early palliative care services as part of a multidisciplinary approach can enhance the quality of life, and perhaps even prolong survival for patients with advanced cancer. Changing impressions of the term palliative care, or substituting the term supportive care, may help to extend the reach of these services.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Galen Switzer, PhD and his research team at the University of Pittsburgh for guidance on survey design and interview techniques. We also thank the participating oncologists and patients.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellowship [R.M.] and The National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [KL2TR000146 to Y.S.]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morrison RS, Meier DE. Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(25):2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp035232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(1):83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, et al. Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):465–473. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pantilat SZ, O'Riordan DL, Dibble SL, Landefeld CS. Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(4):436–473. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps –from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine National Cancer Policy Board. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2001. [Accessed 8 Feb 2013]. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10149&page=R1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancer control: knowledge into action: WHO guide for effective programmes; module 5, Palliative Care. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. [Accessed 08 Feb 2013]. http://www.who.int/cancer/media/FINAL-PalliativeCareModule.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherny N, Catane R, Schrijvers D, et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Program for the integration of oncology and Palliative Care: a 5-year review of the Designated Centers' incentive program. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(2):362–369. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainbird K, Perkins J, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. The needs of patients with advanced, incurable cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(5):759–764. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitmer KM, Pruemer JM, Nahleh ZA, Jazieh AR. Symptom management needs of oncology outpatients. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):628–630. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng WW, Willey J, Palmer JL, et al. Interval between palliative care referral and death among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(5):1025–1032. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osta BE, Palmer JL, Paraskevopoulos T, et al. Interval between first palliative care consult and death in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):51–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuyama RKP, Balliet WP, Ingram KP, et al. Will Patients Want Hospice or Palliative Care if They Do Not Know What It Is? Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2011;13(1):41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahon MM, McAuley WJ. Oncology nurses' personal understandings about palliative care. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(3):E141–E150. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E141-E150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyashita M, Hirai K, Morita T, et al. Barriers to referral to inpatient palliative care units in Japan: a qualitative survey with content analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(3):217–222. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what's in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115(9):2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16(1):105–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, et al. Referral Practices of Oncologists to Specialized Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4380–4386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McInturff B, Harrington L. Public Opinion Strategies. Presentation of 2011 Research on Palliative Care. [Accessed13 Feb 2013];Center to Advance Palliative Care, American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. 2011 Jun 13; http://www.capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/marketing/public-opinion-research/2011-public-opinion-research-on-palliative-care.pdf.

- 29.Hui D, Mori M, Parsons HA, et al. The lack of standard definitions in the supportive and palliative oncology literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(3):582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UPMC Supportive and Palliative Care Program. [Accessed 13 Feb 2013];University of Pittsburgh Schools of Health Sciences. 2012 http://www.upmc.com/Services/palliative-care/Pages/default.aspx.

- 31.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grbich C. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction. London: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastrana T, Junger S, Ostgathe C, et al. A matter of definition—key elements identified in a discourse analysis of definitions of palliative care. Palliat Med. 2008;22(3):222–232. doi: 10.1177/0269216308089803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(21):3490–3496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wenger NS, Vespa PM. Ethical issues in patient-physician communication about therapy for cancer: professional responsibilities of the oncologist. Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 1):43–48. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razzak M. Palliative care: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(4):189. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnold RM. A rose by any other name. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(6):807–811. doi: 10.1089/10966210260498970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Junger S, Payne S, Brearley S, et al. Consensus building in palliative care: a europe-wide delphi study on common understandings and conceptual differences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(2):192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blumberg SJ, Foster EB, Frasier AM, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children's Health. Vital Health Stat. 2007;1(55):1–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in Telephone Survey Non Response Over the Past Quarter Century. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2005;69(1):87–98. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.