Abstract

In the mouse lung, Escherichia coli LPS can decrease surfactant protein–B (SFTPB) mRNA and protein concentrations. LPS also regulates the expression, synthesis, and concentrations of a variety of gene and metabolic products that inhibit SFTPB gene expression. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether LPS acts directly or indirectly on pulmonary epithelial cells to trigger signaling pathways that inhibit SFTPB expression, and whether the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP)–β (CEBPB) is a downstream inhibitory effector. To investigate the mechanism of SFTPB repression, the human pulmonary epithelial cell lines NCI-H441 (H441) and NCI-H820 (H820) and the mouse macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 were treated with LPS. Whereas LPS did not decrease SFTPB transcripts in H441 or H820 cells, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells decreased SFTPB transcripts in H441 and H820 cells, and inhibited SFTPB promoter activity in H441 cells. In the presence of neutralizing anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells did not inhibit SFTPB promoter activity. In H441 cells treated with recombinant TNF protein, SFTPB transcripts decreased, whereas CEBPB transcripts increased and the transient coexpression of CEBPB decreased SFTPB promoter activity. Further, CEBPB short, interfering RNA increased basal SFTPB transcripts and countered the decrease of SFTPB transcripts by TNF. Together, these findings suggest that macrophages participate in the repression of SFTPB expression by LPS, and that macrophage-released cytokines (including TNF) regulate the transcription factor CEBPB, which can function as a downstream transcriptional repressor of SFTPB gene expression in pulmonary epithelial cells.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, acute lung injury, TNF, surfactant

Clinical Relevance

Although the etiology of acute lung injury is complex, many cases are associated with pneumonia or sepsis. In patients with pneumonia or sepsis-induced acute lung injury, pulmonary surfactant protein–B is decreased. Surfactant protein–B is a protein critical in the maintenance of lung function and survival. Bacterial LPS and other microbial components can alter the expression of a variety of proteins, including surfactant protein–B, in laboratory animals. This study investigated the cellular and molecular basis of surfactant protein–B promoter inhibition by LPS. Although LPS does not directly lower surfactant protein–B concentrations in human pulmonary epithelial cells, LPS stimulates macrophages to release cytokines that in turn diminish surfactant protein–B concentrations in epithelial cells.

Surfactant protein–B (SFTPB) is one of the pulmonary surfactant–associated proteins (SFTPA1, SFTPA2, SFTPB, SFTPC, and SFTPD) expressed by alveolar Type II epithelial cells and nonciliated bronchiolar epithelial cells. SFTPB protein is critical for lamellar body packaging, tubular myelin formation, SFTPC processing, and the generation of a surfactant layer capable of reducing surface tension (1–3). Clinically, SFTPB mutations can cause surfactant metabolism dysfunction, pulmonary–1 (Mendelian Inheritance in Man number 265,120) (4).

In addition to hereditary SFTPB deficiency, acute lung injury can lead to decreased SFTPB expression (5–10). The cause of acute lung injury can be direct (e.g., inhaled hazardous chemicals) or indirect (e.g., sepsis). One approach to understanding the pathophysiology of sepsis-induced acute lung injury has involved challenging mice with infectious or noninfectious bacteria, or bacterial components such as LPS. In mice, LPS can decrease lung SFTPB mRNA and protein concentrations (11). LPS induces the production of numerous cytokines and metabolic products, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), ceramide, 15-deoxy-D12, 14-prostaglandin J2, and oxidative stress agents, which inhibit SFTPB expression (12–15). However, the mechanism of SFTPB mRNA and protein decrease by LPS has not been defined. It remains unclear whether LPS acts directly on pulmonary epithelial cells and induces signaling pathways that inhibit SFTPB expression.

LPS also can increase transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP)–β (CEBPB) mRNA concentrations in rat and mouse lungs (16, 17). Because CEBPB is expressed in alveolar Type II cells, alveolar macrophages, and bronchiolar epithelia (16, 18, 19), its induction in response to stimulants such as LPS may play a crucial role during infection, inflammation, and injury. Consistent with this postulate, a recent study reported that CEBPB is a critical regulator of IgG immune complex–induced inflammatory responses and injury in the lung (20). Previously, we reported that CEBPB protein bound to its cognate DNA sequence and repressed mouse Sftpb promoter activity (21). Thus, we hypothesized that the induction by LPS of CEBPB expression may contribute to SFTPB inhibition. To test this hypothesis, SFTPB regulation in pulmonary epithelial cells was investigated after treatment with LPS or a conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophages.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design

More detailed methods are presented in the online supplement. Briefly, to determine whether LPS could act directly on pulmonary epithelial cells and modulate human surfactant protein B (hSFTPB) promoter activity, human pulmonary epithelial cells NCI-H441 (H441), which possess morphological secretoglobin-producing cell–like characteristics (22), were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct containing the hSFTPB promoter region, spanning nucleotides −672 to +42 with respect to the transcription initiation site. The transfected cells were treated with PBS (control) or 0.4 to 12 μg/ml LPS (24 h, 37°C), and promoter activity was measured. To examine endogenous SFTPB gene regulation, H441 cells and NCI-H820 (H820) cells, which possess alveolar Type II epithelial cell–like characteristics (23), were incubated in the absence or presence of LPS. SFTPB transcripts were then assessed by quantitative real-time PCR.

In additional tests, the function of LPS-treated macrophages in SFTPB expression in pulmonary epithelial cells was examined. The mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells were incubated without or with 40 ng/ml or 4 μg/ml LPS (6 h, 37°C). The conditioned medium used to treat H441 cells was diluted 1/50, 1/300, or 1/1,800 to measure hSFTPB promoter activity and SFTPB transcripts, whereas H820 cells were treated with conditioned medium diluted 1/5, and the SFTPB transcripts were measured. To examine whether LPS and the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells affected cell viability, lactate dehydrogenase enzyme release was measured. To determine whether carryover LPS in the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells, complexed with secreted proteins, contributed to the regulatory capacity of the conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophages, the effects of polymixin B on the inhibition of SFTPB transcripts in H441 cells or the induction of superoxide dismutase–2 mitochondrial (SOD2) transcripts in H441 and RAW264.7 cells were investigated. To begin identifying the paracrine factors in the conditioned medium that could alter SFTPB promoter activity, conditioned media of control and LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells were filtered, using a 3-kD filter. The fraction of conditioned medium retained by the filter (retentate) and the filtrate were then recovered and used to treat H441 cells transfected with the luciferase reporter construct. A multiplex protein analysis was also performed to determine the amount of 20 cytokines in conditioned media of control and LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells.

To assess whether TNF in the conditioned medium could inhibit hSFTPB promoter activity, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells was incubated without or with neutralizing anti-TNF antibody. Conditioned medium containing control vehicle PBS, control goat IgG, or neutralizing anti-TNF antibody was incubated (30 min, 23°C) before adding to H441 cells transfected with hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter. To determine whether the inhibition of SFTPB transcripts was accompanied by an induction of CEBPB, SFTPB and CEBPB transcripts were measured in H441 cells treated with TNF for 6 or 23 hours. In addition, to examine whether CEBPB inhibits SFTPB promoter activity in H441 cells, luciferase reporter constructs containing hSFTPB promoter deletion fragments were cotransfected with an expression plasmid containing CEBPB cDNA, and hSFTPB promoter activity was measured. Finally, the effects of CEBPB short, interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection on SFTPB transcripts were analyzed.

Results

Conditioned Medium of LPS-Treated RAW264.7 Cells Inhibits hSFTPB Promoter Activity and Decreases SFTPB Transcripts in H441 cells

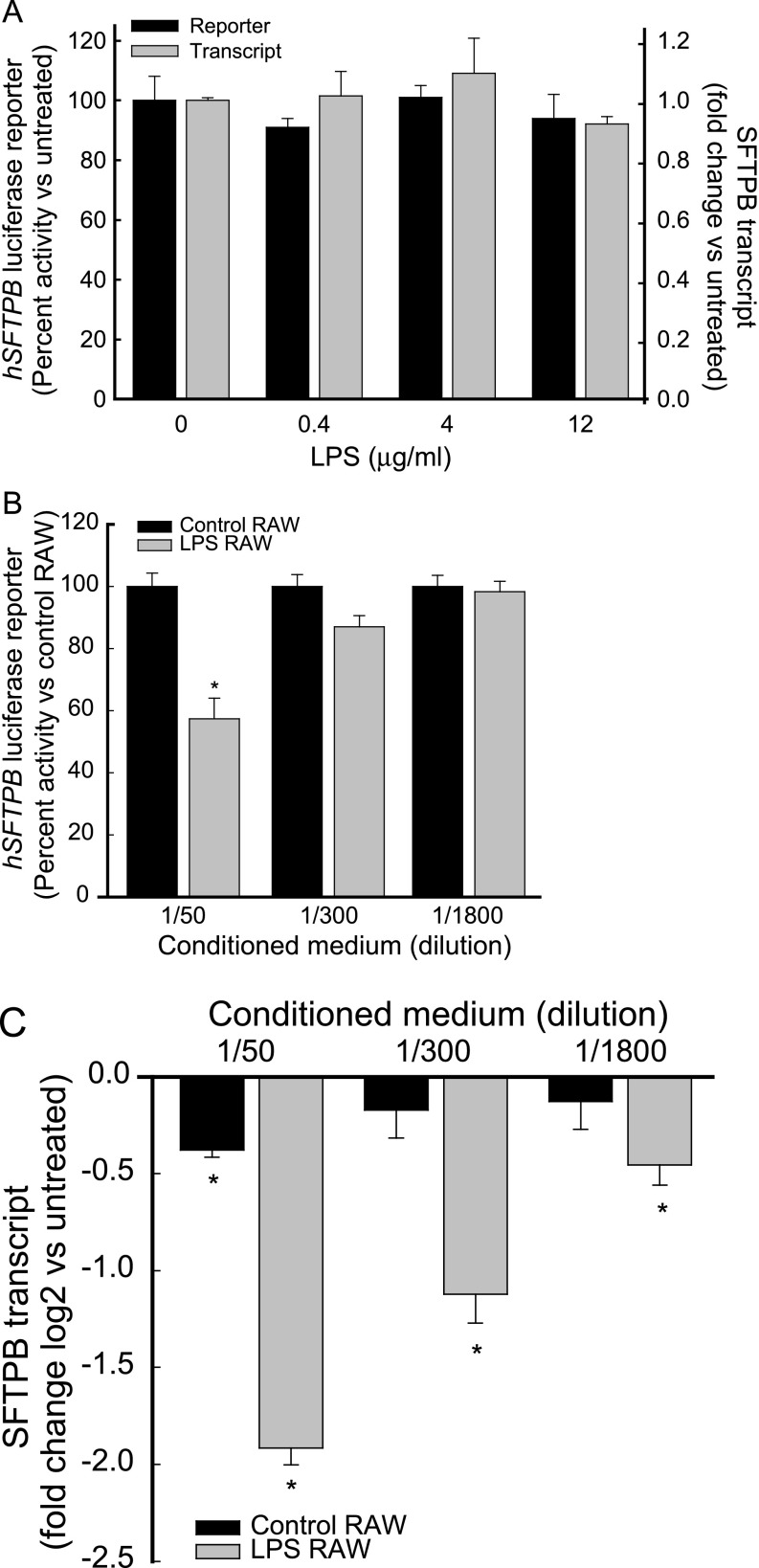

A previous in vivo study in mice reported that aerosolized LPS decreased SFTPB mRNA and protein concentrations, which led to surfactant and respiratory dysfunction (11). However, another in vitro study reported that LPS-treated mouse macrophages increased a β-galactosidase (lacZ) reporter under the control of a 1.5-kb hSFTPB promoter in cocultured mouse alveolar Type II epithelial cells (24). To investigate whether LPS acted directly on pulmonary epithelial cells and modulated hSFTPB promoter activity, H441 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct containing the hSFTPB promoter region, spanning nucleotides −672 to +42 with respect to the transcription initiation site. The treatment of transfected H441 cells with LPS (≤ 12 μg/ml) did not inhibit or induce hSFTPB promoter activity (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophage RAW264.7 cells inhibited human surfactant protein–B (hSFTPB) promoter activity and decreased surfactant protein–B (SFTPB) transcripts in human pulmonary epithelial cells NCI-H441 (H441). H441 cells were incubated (for 22–24 h, at 37°C) in (A) the absence or presence of LPS or (B and C) the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells incubated (for 6 h, at 37°C) in the absence (black bars, Control RAW) or presence (gray bars, LPS RAW) of 4 μg/ml LPS. The conditioned medium added to H441 cells was diluted 50- to 1,800-fold with serum-free RPMI-1640. hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter activity is expressed (A and B) as percent activity relative to control samples. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 4–6). SFTPB transcripts were determined by real-time PCR analysis and are expressed as (A, gray bars) fold change or (C) fold change log 2 relative to control samples. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 6). *Decreased in comparison with untreated control samples (P < 0.001) as determined by ANOVA, with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures.

To determine whether the lack of response of hSFTPB promoter activity to LPS might be explained by the occurrence of cis-acting regulatory elements not included in the promoter–reporter construct or another gene/transcript regulatory mechanism, RNA isolated from H441 cells incubated in the absence or presence of LPS was assessed by quantitative real-time PCR for SFTPB transcripts. The treatment of H441 cells with LPS, compared with untreated cells, did not inhibit or induce endogenous SFTPB transcripts (Figure 1A).

Previously, Wispe and colleagues postulated that macrophage-derived cytokines may control surfactant protein expression (13). Because alveolar macrophages respond to bacteria and bacterial cell components, including LPS, and can activate epithelial cells by producing various cytokines (13, 25–27), we reasoned that LPS may modulate SFTPB promoter activity and SFTPB transcripts in pulmonary epithelial cells via the activation of alveolar macrophages. To examine the function of macrophages in SFTPB expression, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells was tested, and was found to inhibit hSFTPB promoter activity in H441 cells (Figure 1B). Similarly, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells decreased endogenous SFTPB transcripts in H441 cells (Figure 1C). Interestingly, control RAW264.7 conditioned medium (dilution, 1/50) also slightly decreased SFTPB transcripts. Consistent with the response of the secretoglobin-producing cell–like H441 cells, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, but not LPS treatment, decreased endogenous SFTPB transcripts in the alveolar Type II epithelial cell–like H820 cells (Figure E1 in the online supplement). In agreement with previous studies on TNF treatment (13), the incubation of H441 or H820 cells with the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (24 hours, 37°C) did not alter microscopic appearances. In addition, percent lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme release was not significantly different from that of control cells. In H441 cells, the percent LDH release, compared with that of control cells, was measured at 0.5 ± 0.1 when cells were incubated with the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells treated with 40 ng/ml LPS, and 0.1 ± 0.2 when incubated with the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells treated with 4 μg/ml LPS. In H820 cells, the percent LDH release, compared with that of control cells, was measured at 0.2 ± 1.7 when cells were incubated with the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells treated with 40 ng/ml LPS, and 1.3 ± 1.6 when incubated with the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells treated with 4 μg/ml LPS. In RAW264.7 cells, the percent LDH release, compared with that of control cells, was measured at 0.1 ± 0.2 when cells were incubated with 40 ng/ml LPS, and 0.1 ± 0.1 when incubated with 4 μg/ml LPS

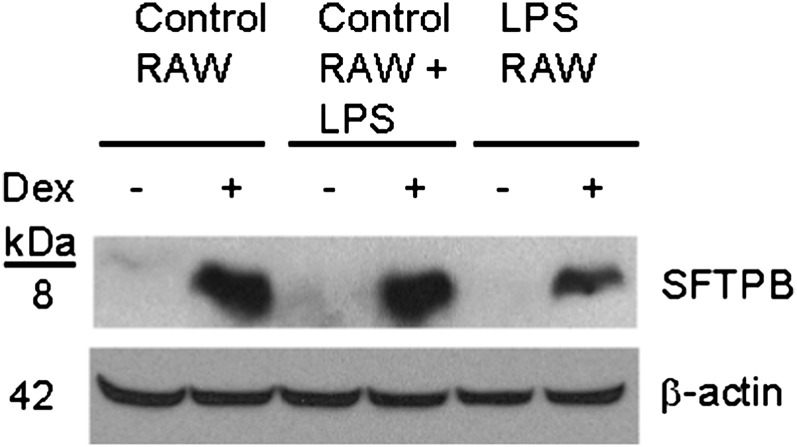

Decrease of SFTPB Transcripts by Conditioned Medium of LPS-Treated RAW264.7 Cells Inhibits Induction of SFTPB Protein

To investigate whether the decrease in SFTPB transcripts by the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells was accompanied by decreased SFTPB protein, H441 cells were incubated with or without dexamethasone. Previous studies demonstrated that dexamethasone induces SFTPB protein (28). Dexamethasone-induced SFTPB protein decreased in H441 cells treated with the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 2, lane 6), compared with the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 2, lane 2). The addition of LPS to the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 2, lane 4) did not alter the response, compared with the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 2, lane 2).

Figure 2.

Conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophage RAW264.7 cells decreased SFTPB protein expression in pulmonary epithelial H441 cells. H441 cells were preincubated (for 24 h, at 37°C) with the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells incubated (for 6 h, at 37°C) in the absence (Control RAW, lanes 1 and 2) or presence (LPS RAW, lanes 5 and 6) of 40 ng/ml LPS, and further incubated (for 24 h, at 37°C) in the absence (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or presence (lanes 2, 4, and 6) of 100 nM dexamethasone (Dex). The addition of 0.8 ng/ml LPS to the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells (Control RAW + LPS, lanes 3 and 4) did not alter the response to the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells (Control RAW, lanes 1 and 2). The conditioned medium added to H441 cells was diluted 50-fold with serum-free RPMI-1640. H441 protein lysate (60 μg/lane) was analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-SFTPB antibody and anti–β-actin as a loading control.

The Regulatory Capacity of the Conditioned Medium of LPS-Treated RAW264.7 Cells Is Not Attributable to Carryover LPS Complexed with Secreted Proteins

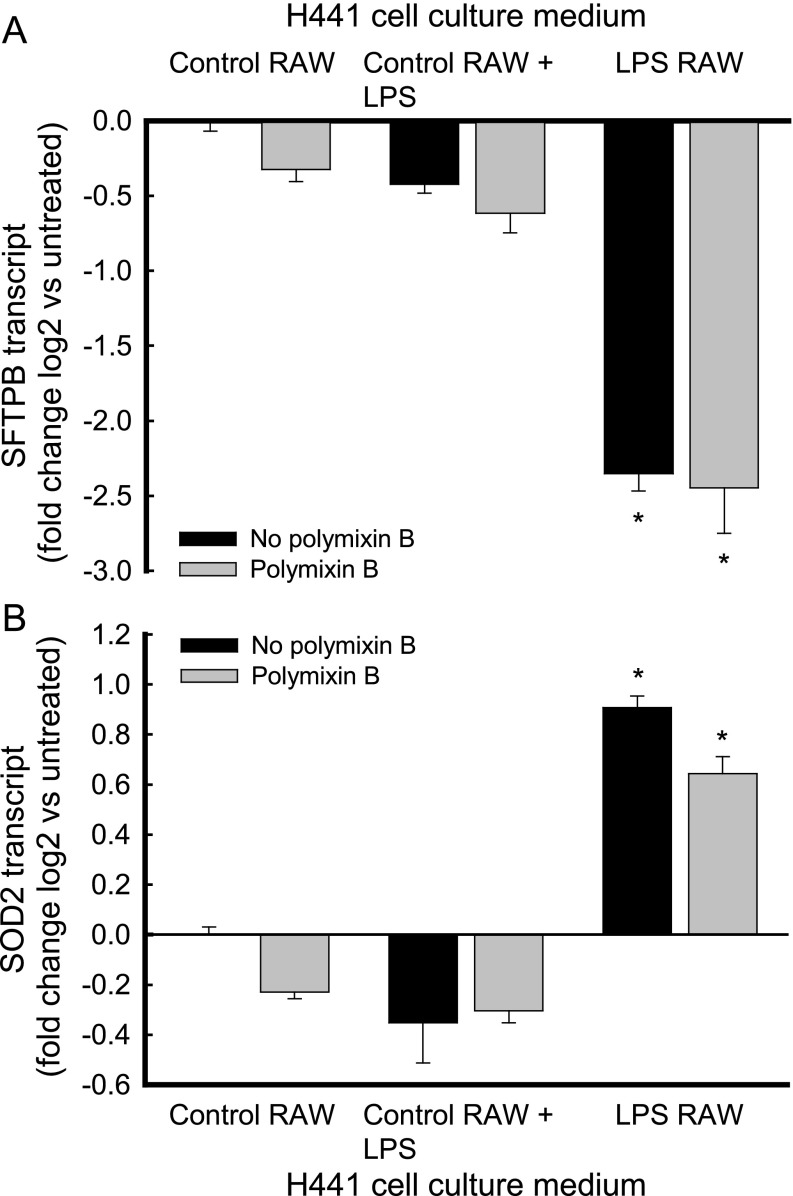

To investigate whether carryover LPS in the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells complexed with secreted proteins contributed to the regulatory capacity of the conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophages, SFTPB transcripts were measured in H441 cells incubated with conditioned medium containing polymixin B. To evaluate the specificity of the inhibitory effect of the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells on SFTPB transcripts, SOD2 transcripts were measured (13).

Polymixin B did not alter the repression of SFTPB transcripts via the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 3A). Unlike its inhibitory effect on SFTPB transcripts, the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells induced SOD2 transcripts in H441 cells, and the addition of polymixin B did not alter this induction (Figure 3B). In contrast, polymixin B inhibited the induction of SOD2 transcripts by LPS in RAW264.7 cells (Figure E2 in the online supplement). In addition, polymixin B did not significantly alter SFTPB (Figure 3A) or SOD2 (Figure 3B) transcripts after incubation with control RAW264.7 conditioned medium or control RAW264.7 conditioned medium to which 0.8 ng/ml LPS had been added. Together, these results suggest that factors released by LPS-treated macrophages decreased SFTPB and increased SOD2 transcripts in H441 cells.

Figure 3.

Polymixin B inhibited neither the decrease of SFTPB transcripts nor the increase of superoxide dismutase–2 (SOD2) transcripts in pulmonary epithelial H441 cells treated with the conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophage RAW264.7 cells. H441 cells were incubated (for 18 h, at 37°C) without (black bars, no polymixin B) or with (gray bars, polymixin B) 20 μg/ml of polymixin B. (A) SFTPB transcripts decreased after incubation with the conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells treated with LPS (black bar, LPS RAW). This effect was not altered by the addition of polymixin B (gray bar, LPS RAW). Polymixin B did not significantly alter SFTPB transcripts after incubation with the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells (Control RAW) or the conditioned medium of untreated RAW264.7 cells, to which 0.8 ng/ml LPS had been added (Control RAW + LPS). (B) Polymixin B also did not alter the increased SOD2 concentrations measured in H441 cells. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3). *Significantly different, compared with untreated control samples (P < 0.001), as determined by ANOVA with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures.

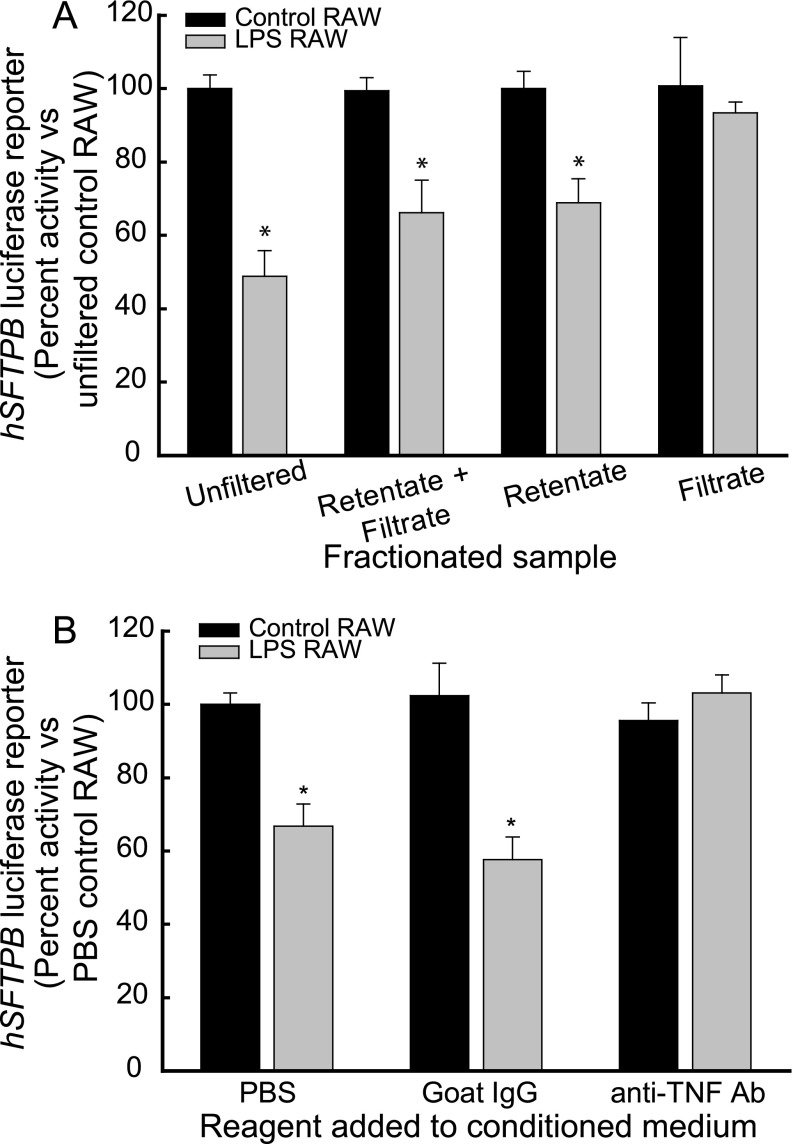

Paracrine Factors of Greater than 3 kD Inhibit hSFTPB Promoter Activity

The LPS stimulation of macrophages leads to the induction of an array of potent cytokines (e.g., TNF) and nonprotein mediators (e.g., ceramide or eicosanoids) (29–32). To begin identifying the paracrine factors that mediate SFTPB promoter activity inhibition, conditioned media of control and LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells were filtered using a 3-kD filter. The fraction of conditioned medium retained by the filter (retentate) and the filtrate were then recovered and used to treat H441 cells transfected with the luciferase reporter construct pGL4-hSFTPB−672/+42. The retentate fraction of the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, similar to a combination of the retentate plus filtrate fractions and the unfiltered medium, inhibited hSFTPB promoter activity (Figure 4A). However, the filtrate fraction of LPS-treated RAW264.7 conditioned medium did not decrease hSFTPB promoter activity. In addition, the conditioned medium of control RAW264.7 cells, whether fractionated or not, did not inhibit hSFTPB promoter activity (Figure 4A). These results suggest that a protein of greater than 3 kD in the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells was responsible for the hSFTPB promoter inhibition.

Figure 4.

Identification of TNF as a key mediator of hSFTPB promoter activity inhibition by the conditioned medium of LPS-treated macrophage RAW264.7 cells. (A) LPS-induced paracrine factors of more than 3 kD inhibited hSFTPB promoter activity in H441 cells. The conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells incubated in the absence (black bars, Control RAW) and presence (gray bars, LPS RAW) of 4 μg/ml LPS was filtered using a 3-kD filter. The fraction retained by the filter (retentate) and the filtrate were recovered and added (diluted 50-fold), in combination or separately, to H441 cells transfected with the hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter construct pGL4-hSFTPB−672/+42 (for 22–24 h, at 37°C). hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter activity is expressed as percent activity relative to cells treated with the unfiltered conditioned medium of control RAW264.7 cells. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3). (B) The conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells did not inhibit hSFTPB promoter activity in H441 cells in the presence of neutralizing anti-TNF antibody. The conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells incubated in the absence (black bars, Control RAW) or presence (gray bars, LPS RAW) of 4 μg/ml LPS was preincubated (for 30 min, at 23°C) in the presence of PBS vehicle control (PBS), 4 μg/ml nonimmune goat IgG (Goat IgG), or 4 μg/ml neutralizing anti-TNF antibody (anti-TNF Ab) and added to H441 cells transfected with the hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter construct, pGL4-hSFTPB−672/+42 (for 22–24 h, at 37°C). hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter activity is expressed as percent activity relative to cells treated with the conditioned medium of control RAW264.7 cells plus PBS. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 6). *Significntly different compared with control samples (P < 0.001), as determined by ANOVA with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures.

TNF Protein in Conditioned Medium of LPS-Treated RAW264.7 Cells Inhibits hSFTPB Promoter Activity

To determine the amount of selected cytokines in the conditioned media of control and LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, multiplex protein analysis was performed. A Luminex 200 (Bio-Plex200; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to measure the cytokines chemokine (C-C motif) ligand–2 (CCL2, also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, or MCP1), CCL3 (also known as macrophage inflammatory protein–1α, or MIP-1 α), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand–1 (CXCL1, also known as GRO-1 or melanoma growth–stimulating activity–α), CXCL9, CXCL10, colony-stimulating factor–2 (granulocytes and macrophages) (CSF2, also known as granulocyte–macrophage colony–stimulating factor, or GM-CSF), fibroblast growth factor–2 (FGF2, also known as FGF basic), IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-1B, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12B, IL-13, IL-17A, TNF, and vascular endothelial growth factor–A. The cytokines CCL2, CCL3, CXCL1, CXCL10, FGF2, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF were detected in the untreated conditioned medium (Table 1). After LPS stimulation, CCL2, CCL3, CSF2, CXCL1, CXCL10, FGF2, IFN-γ, IL1B, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12B, and TNF increased in the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, compared with the conditioned medium of control RAW264.7 cells. Of these, CCL3, TNF, and CCL2 exhibited the highest concentrations (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

CYTOKINES IN CONDITIONED MEDIUM OF macrophage RAW2647 CELLS

| Cytokine | Cytokine Concentration (pg/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control RAW | 40 ng/ml LPS RAW |

4 μg/ml LPS RAW 1/300 |

|||

| Undiluted | Diluted 1/50 | Undiluted | Diluted 1/50 | ||

| CCL2 |

61 |

2,536 |

51 |

6,478 |

130 |

| CCL3 |

7,310 |

145,236 |

2,905 |

87,872 |

1,757 |

| CSF2 |

ND |

92 |

1.8 |

542 |

11 |

| CXCL1 |

62 |

ND |

ND |

124 |

2.5 |

| CXCL10 |

9 |

982 |

20 |

989 |

20 |

| CXCL9 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| FGF2 |

29 |

42 |

<1.0 |

46 |

<1.0 |

| IFN-γ |

ND |

21 |

<0.5 |

21 |

<0.5 |

| IL-1A |

ND |

ND |

ND |

<0.6 |

<0.1 |

| IL-1B |

ND |

106 |

2 |

90 |

1.8 |

| IL-2 |

ND |

46 |

<1.0 |

59 |

1 |

| IL-4 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

10 |

0.2 |

| IL-5 |

ND |

297 |

6 |

242 |

5 |

| IL-6 |

21 |

154 |

3 |

1,225 |

25 |

| IL-10 |

<0.5 |

179 |

3.6 |

672 |

13 |

| IL-12B |

ND |

47 |

<1.0 |

54 |

1 |

| IL-13 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| IL-17A |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| TNF |

32 |

20,399 |

408 |

15,600 |

312 |

| VEGF | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Definition of abbreviations: CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CSF, colony-stimulating factor; CXCL, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; ND, below the lower limit of detection; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

RAW264.7 cells (20 × 106) were seeded in 10-cm dishes. After 24 hours, cells were rinsed twice with PBS and 6 ml serum-free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), without (control RAW) or with 40 ng/ml or 4 μg/ml LPS (LPS RAW) added, and the conditioned medium was collected after 6 hours of incubation. The concentration of cytokines in the conditioned medium was determined using a Cytokine 20-Plex (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY).

Previously, TNF was demonstrated to decrease SFTPB mRNA stability (33, 34) and inhibit SFTPB promoter activity in H441 cells (12, 35). To assess the relative contribution of TNF protein to the inhibition of the hSFTPB promoter via the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, the effect of neutralizing anti-TNF antibody on hSFTPB promoter inhibition was determined. Conditioned medium containing control vehicle PBS, control goat IgG, or neutralizing anti-TNF antibody was incubated (30 min, 23°C) before being added to H441 cells transfected with luciferase reporters. The conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells inhibited the hSFTPB promoter in the presence of control goat IgG, but not in the presence of anti-TNF antibody (Figure 4B). In addition, H441 cells transfected with the luciferase reporter construct containing the hSFTPB promoter region −672/+42 were treated with human recombinant TNF protein. Human recombinant TNF protein inhibited hSFTPB promoter reporter activity (Figure 5A). The conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells used to treat H441 cells also contained approximately 2 ng/ml CCL3. The treatment of H441 cells with 1 or 10 ng/ml CCL3 did not alter SFTPB transcripts in control or TNF-treated H441 cells (Figure E3 in the online supplement). These results suggest that the TNF released by LPS-treated macrophages is a key contributor to hSFTPB promoter inhibition by LPS.

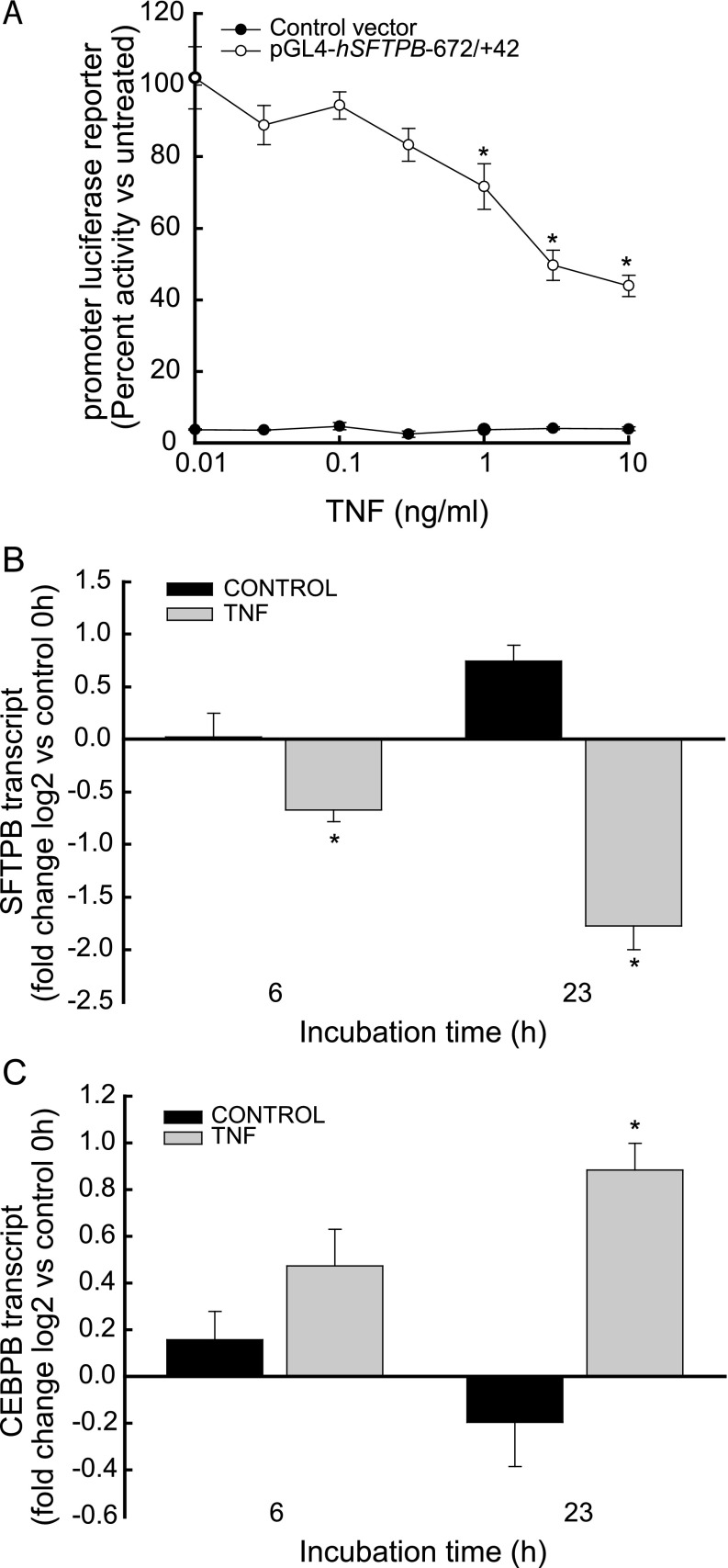

Figure 5.

Human recombinant TNF protein (A) inhibited hSFTPB promoter activity, (B) decreased SFTPB transcripts, and (C) increased CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP)–β (CEBPB) transcripts in pulmonary epithelial H441 cells. (A) H441 cells transfected with promoterless (solid circles, control vector) or hSFTPB promoter containing luciferase reporter (open circles, pGL4-hSFTPB−672/+42) were incubated for 22–24 hours with increasing TNF protein concentrations. Promoter luciferase reporter activity is expressed as percent activity relative to hSFTPB promoter reporter transfected cells incubated in the absence of TNF. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 6). *Significantly different, compared with no TNF (P < 0.001), as determined by ANOVA with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures. (B) TNF decreased SFTPB transcripts. RNA was isolated from H441 cells incubated in the absence (black bars, Control) or presence (gray bars, TNF) of 5 ng/ml TNF protein for 0, 6, or 23 hours. (C) TNF increased CEBPB transcripts. RNA was isolated from H441 cells incubated in the absence (black bars, Control) or presence (gray bars, TNF) of 5 ng/ml TNF protein for 0, 6, or 23 hours. SFTPB and CEBPB transcripts were determined by real-time PCR analysis, and are expressed as fold change log 2 relative to transcripts in RNA samples isolated at the 0-hour time point. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 4). *Significantly different, compared with 0 hours (P < 0.001), as determined by ANOVA with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures.

Coordinated TNF-Mediated SFTPB Inhibition and Increased CEBPB Transcripts

Previously, we reported that CEBPB is a critical regulator of SFTPB expression (21). Specifically, the mouse Sftpb promoter contains the CEBPB DNA recognition element, the CEBPB protein bound to the endogenous Sftpb promoter, and in vitro translated CEBPB protein heterodimerized with JUN protein, which inhibits SFTPB expression. To determine whether the inhibition of SFTPB transcripts was accompanied by an induction of CEBPB transcripts, H441 cells were treated with TNF for 6 and 23 hours. TNF, compared with no treatment, inhibited SFTPB (Figure 5B) and induced CEBPB (Figure 5C) transcripts in a time-dependent fashion.

CEBPB Coexpression Inhibited Transient Reporter Activity of hSFTPB Promoter Deletion Fragments in H441 Cells

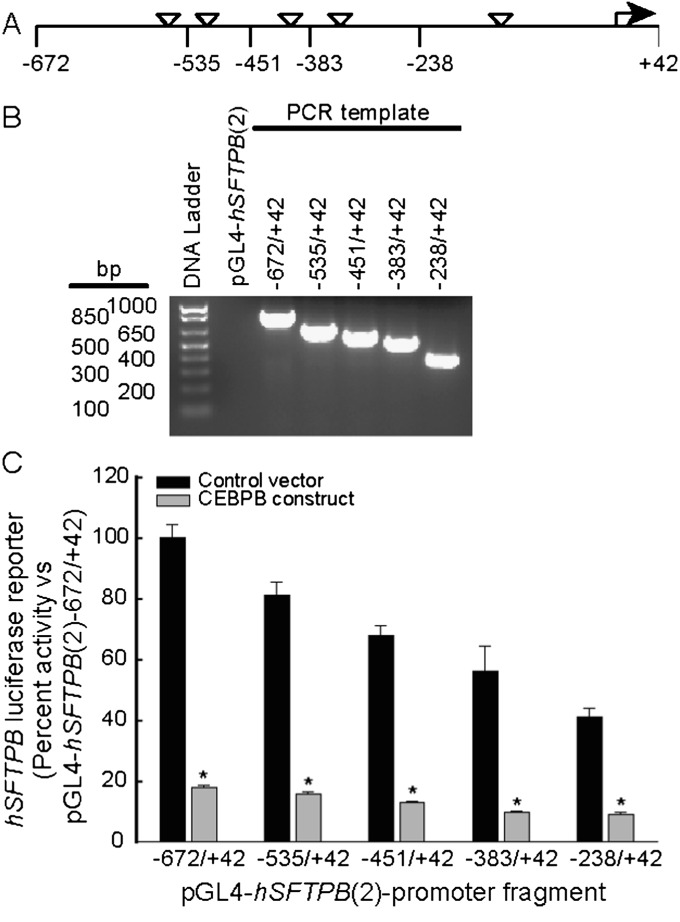

CEBPB may inhibit hSFTPB promoter activity by binding to the SFTPB promoter region, interacting with SFTPB transcription complex components and/or through other mechanisms. The hSFTPB promoter region −672 to +42 contains five putative CEBPB binding sites and other putative recognition elements for 19 out of the 80 CEBPB-associated transcription factors recently reported by the Encylopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Project (36). To begin investigating the mechanisms of SFTPB transcriptional inhibition by CEBPB, luciferase reporter constructs containing hSFTPB promoter deletion fragments were cotransfected with an expression plasmid containing CEBPB cDNA. The coexpression of CEBPB inhibited the promoter reporter activity of all deletion constructs (Figure 6). These results suggest that the increase or activity of CEBPB protein in pulmonary epithelial cells may contribute to the inhibition of the hSFTPB promoter, and that the −238/+42 promoter region contained CEBPB protein–responsive or coresponsive regulatory elements.

Figure 6.

CEBPB coexpression inhibited promoter reporter activity of hSFTPB promoter deletion fragments in pulmonary epithelial H441 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the proximal hSFTPB promoter region containing putative CEBPB recognition sites (inverted triangles) and the nucleotide numbers of the deletion fragments generated. Exonuclease III digestion was used to generate hSFTPB promoter reporter deletion constructs in the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL4–10. (B) Agarose gel analysis of PCR products of the hSFTPB promoter deletion fragments generated. (C) Inhibition of hSFTPB promoter reporter activity by CEBPB coexpression. hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter constructs were cotransfected with an expression plasmid containing no cDNA (black bars, Control vector) or CEBPB cDNA (gray bars, CEBPB construct) into H441 cells. hSFTPB promoter luciferase reporter activity is expressed as percent activity relative to the pGL4-hSFTPB (2)−672/+42 reporter construct cotransfected with control vector. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 4). *Significantly different, compared with control samples (P < 0.001), as determined by ANOVA with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures.

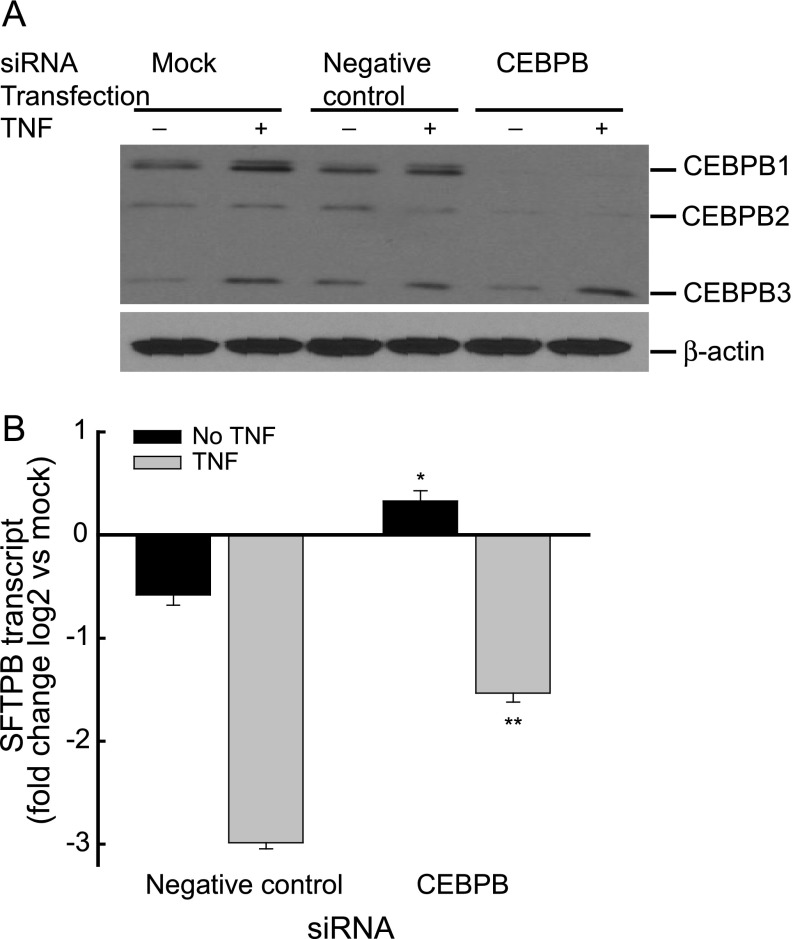

CEBPB Targeting siRNA Countered SFTPB Inhibition in H441 Cells

CEBPB protein is encoded by a single intronless gene that is expressed as three translation products, namely, CEBPB1, CEBPB2, and CEBPB3. To investigate the function of CEBPB expression further in SFTPB transcript regulation, H441 cells were transfected with nontargeting negative control siRNA or CEBPB siRNA. CEBPB1 and CEBPB2 protein concentrations decreased in CEBPB siRNA–transfected cells, compared with cells transfected with the transfection reagent without siRNA (mock-transfected) or negative control siRNA (Figure 7A). In H441 cells transfected with CEBPB siRNA, the basal SFTPB transcript increased, and the TNF-dependent decrease of SFTPB transcript was diminished (Figure 7B), suggesting that either one or both of the larger CEBPB protein isoforms inhibits SFTPB expression.

Figure 7.

CEBPB protein expression contributes to decreased SFTPB transcripts in pulmonary epithelial H441 cells. (A) CEBPB1 and CEBPB2 protein isoforms decreased in H441 cells treated with CEBPB short, interfering RNA (siRNA), without or with 5 ng/ml TNF. Cells were treated with transfection reagent without siRNA (Mock), nontargeting siRNA (Negative control), or CEBPB siRNA (CEBPB). Western blot analysis of the H441 cell lysate preparation (20 μg/lane) used anti-CEBPB and anti–β-actin antibodies. (B) The TNF-induced decreased SFTPB transcript was diminished in H441 cells treated with CEBPB siRNA. Cells were transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Negative control) or CEBPB siRNA (CEBPB) without (black bars, No TNF) or with (gray bars, TNF) 5 ng/ml TNF. SFTPB transcripts were determined by real-time PCR analysis, and are expressed as fold change log 2 relative to mock-transfected cells. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3). *Significantly different compared with untreated negative control samples (P < 0.001). **Significantly different compared with TNF-treated negative control samples (P < 0.001), as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple-comparison procedures.

Discussion

Although the etiology of acute lung injury is complex, many cases of adult acute lung injury are associated with pneumonia or nonpulmonary sepsis (37). In patients with pneumonia or sepsis-induced acute lung injury, altered pulmonary surfactant composition and concentrations have been reported (5, 7–9). A loss of pulmonary surfactant function can decrease pulmonary compliance and compromise gas exchange (38).

The administration of bacterial components such as LPS into animals is a common experimental approach used to model lung injury attributable to sepsis (39). In mice, exposure to aerosolized LPS decreases SFTPB mRNA and protein concentrations (11). However, the cellular basis for the action of LPS in SFTPB expression is not fully understood. The lung is continuously exposed to potential airborne and nasopharynx microflora-derived pathogens and particles. Under normal circumstances, the lung is protected from inflammation and infection in part by mucociliary clearance and phagocytosis (40), and in part by pulmonary epithelial cell hyporesponsiveness that limits inopportune inflammation in response to trace amounts of LPS (41). However, pathogenic infection and septicemia comprise major causes of pulmonary diseases such as acute lung injury. After their release, bacterial LPS and other microbial components can alter the expression level in a wide variety of cellular proteins, including transcription factors, cytokines, and SFTPB.

The goal of the present study was to investigate the mechanism underlying the LPS inhibition of hSFTPB promoter activity and SFTPB transcripts in H441 and H820 cells. The use of these cells has its limitations, because H441 and H820 cells comprise adenocarcinoma cell lines. However, among 33 lung derived cell lines, H441 and H820 expressed SFTPB (13, 22, 23). These cells represent a homogeneous cell population for testing SFTPB transcriptional repression by LPS, and for providing an approach to the problem of SFTPB expression maintenance in vitro and unavoidable cell population heterogeneity within and between different primary cell preparations. The literature does not make clear whether respiratory epithelial cells respond directly to LPS. Although A549 cells (27, 42–45) and tracheobronchial epithelial cells (46–48) were reported to respond moderately or not at all to LPS in vitro, others reported the release of cytokines and neutrophil chemotaxins (49–51). The nonresponsiveness or hyporesponsiveness of epithelial cells to LPS has been attributed to the absence of CD14 or Toll-like receptor–4 expression (44, 52, 53). The assay endpoints measured in these various studies may also account, in part, for the discrepancies. Our findings suggest that Escherichia coli 055:B5 LPS does not directly modulate hSFTPB promoter activity and SFTPB transcripts in H441 cells and H820 cells.

In contrast to the conflicting reports on the actions of LPS in pulmonary epithelial cells, the responsiveness of alveolar macrophages to LPS is clear. Alveolar macrophages are sensitive to LPS in vitro and in vivo (54–57). We found that the treatment of H441 cells with a conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells inhibited hSFTPB promoter activity and SFTPB transcripts, but induced SOD2 transcripts, in H441 cells. Further, preincubation with polymixin B did not alter the decrease in SFTPB transcripts or diminish the increase in SOD2 transcripts induced by the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells. Polymixin B is a cationic polypeptide that binds to the lipid-A portion of LPS, resulting in an inhibition of LPS activity (58). These results suggest that paracrine factors produced by macrophages, in part, mediate the inhibition of SFTPB expression.

In addition to the macrophage-directed regulation of epithelial cell gene expression, epithelial cells can also influence macrophage function. For example, LPS can induce CXCL2 (also known as MIP-2) and CCL2 (also known as MCP-1) secretion from pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells that can recruit and activate monocytes, neutrophils, and T-lymphocytes (59), and the conditioned medium of LPS-treated alveolar epithelial cells can alter macrophage migration, phagocytosis, the intracellular control of bacterial growth, and morphology (60, 61).

The LPS treatment of macrophages modulates, in addition to other effects, the expression of many mediators, including cytokines and toxic factors (29, 30, 32). Analysis of the fractionated conditioned medium of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells indicated that fractions of greater than 3 kD mediated the inhibition of the SFTPB promoter. In particular, the findings observed using neutralizing anti-TNF antibodies and human recombinant TNF protein suggest that TNF is a key factor in the inhibition of SFTPB expression by LPS. TNF protein has been detected in the serum of patients with septic shock (∼ 1–3 ng/ml) and in bronchopulmonary secretions of patients with acute lung injury (∼ 12 ng/ml) (62). The conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, which contained approximately 0.3 ng/ml TNF, inhibited SFTPB transcripts in H441 cells. Although alveolar macrophages produce TNF in pulmonary sepsis (63), peritoneal macrophages are also likely to contribute to circulating TNF in nonpulmonary sepsis. For example, peritoneal macrophage–derived TNF and IL-6 concentrations correlated with survival in mice after cecal ligation and puncture (64). In addition, the effects of TNF can be countered by TNF antagonists (e.g., soluble TNF receptors), which can modify responses in vivo (65).

Although our results with anti-TNF antibodies suggest that TNF represents a key mediator of SFTPB promoter activity inhibition, a number of additional LPS-induced cytokines may also modulate TNF activity, because the biologic effects of cytokines are controlled by context (66). The TNF concentration determined in the conditioned medium (diluted 1/50) was approximately 0.3 ng/ml (Table 1), which was below the 3–5 ng/ml TNF dose that produced nearly equivalent hSFTPB promoter activity inhibition (Figures 1B and 5). Of the 20 cytokine concentrations determined in the control conditioned medium of RAW264.7 cells, low concentrations were detected for eight cytokines, whereas in the conditioned medium of LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, an induced signal was detected for 15 cytokines that may influence the H441 cell response to TNF. In particular, IL4 has been reported to decrease SFTPB expression in vivo (67), whereas IL-6 induces SFTPB expression (24, 68). Moreover, although IFN-γ did not affect SFTPB mRNA concentrations in fetal alveolar epithelial cell explants and adult alveolar epithelial cells (69, 70), IFN-γ did decrease mature SFTPB protein concentrations in adult alveolar epithelial cells, likely because of insufficient processing (70). Furthermore, CSF2 influences SFTPB homeostasis (71, 72).

Alterations of SFTPB mRNA stability and reduced binding of the transcription factor NKX2–1 (homeobox protein Nkx2.1) to the SFTPB promoter have been reported as possible mechanisms of inhibition of SFTPB expression by TNF (33–35). The molecular mediators of altered mRNA stability and NKX2–1 binding remain unknown. We previously reported that the binding of CEBPA and/or CEBPB to the SFTPB promoter may mediate an inhibition of SFTPB expression by JUN (21). Because LPS treatment was reported to induce CEBPB, but not CEBPA expression, in mouse lungs (17), we investigated SFTPB and CEBPB transcripts in relation to LPS stimulation. TNF inhibited SFTPB transcripts while inducing CEBPB transcripts. In addition, the exogenous expression of CEBPB inhibited hSFTPB promoter reporter activity, whereas CEBPB siRNA diminished SFTPB inhibition. The observed decreased SFTPB transcripts, but not decreased hSFTPB promoter activity, by the conditioned medium of control cells would support a mechanism of cytokine-mediated inhibition that involves CEBPB-mediated promoter repression, a loss of NKX2–1 promoter binding, and decreased mRNA stability. In conclusion, these findings suggest that macrophages mediate LPS-induced SFTPB repression, and that macrophage-released cytokines inducing CEBPB expression and activity can modulate SFTPB promoter activity.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants ES015675, HL077763, and HL085655 (G.D.L) and ES010859 and HL114795 (L.A.O.).

Author Contributions: K.B. and G.D.L. were responsible for the conception and design of the study. K.B., M.D.G., S.E.M., L.A.O., and G.D.L. were responsible for analysis and interpretation. K.B. and G.D.L. were responsible for drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0283OC on April 3, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Clark JC, Wert SE, Bachurski CJ, Stahlman MT, Stripp BR, Weaver TE, Whitsett JA. Targeted disruption of the surfactant protein B gene disrupts surfactant homeostasis, causing respiratory failure in newborn mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7794–7798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stahlman MT, Gray MP, Falconieri MW, Whitsett JA, Weaver TE. Lamellar body formation in normal and surfactant protein B–deficient fetal mice. Lab Invest. 2000;80:395–403. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vorbroker DK, Profitt SA, Nogee LM, Whitsett JA. Aberrant processing of surfactant protein C in hereditary SP-B deficiency. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L647–L656. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.4.L647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Nogee LM. Genetic disorders of surfactant dysfunction. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12:253–274. doi: 10.2350/09-01-0586.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregory TJ, Longmore WJ, Moxley MA, Whitsett JA, Reed CR, Fowler AA, III, Hudson LD, Maunder RJ, Crim C, Hyers TM. Surfactant chemical composition and biophysical activity in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1976–1981. doi: 10.1172/JCI115523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene KE, Wright JR, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, Caldwell E, Wong WB, Hull W, Whitsett JA, Akino T, Kuroki Y, et al. Serial changes in surfactant-associated proteins in lung and serum before and after onset of ARDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1843–1850. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9901117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pison U, Obertacke U, Brand M, Seeger W, Joka T, Bruch J, Schmit-Neuerburg KP. Altered pulmonary surfactant in uncomplicated and septicemia-complicated courses of acute respiratory failure. J Trauma. 1990;30:19–26. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhuizen RA, McCaig LA, Akino T, Lewis JF. Pulmonary surfactant subfractions in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1867–1871. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunther A, Siebert C, Schmidt R, Ziegler S, Grimminger F, Yabut M, Temmesfeld B, Walmrath D, Morr H, Seeger W. Surfactant alterations in severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and cardiogenic lung edema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:176–184. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beers MF, Atochina EN, Preston AM, Beck JM. Inhibition of lung surfactant protein B expression during Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in mice. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;133:423–433. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingenito EP, Mora R, Cullivan M, Marzan Y, Haley K, Mark L, Sonna LA. Decreased surfactant protein–B expression and surfactant dysfunction in a murine model of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:35–44. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.1.4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparkman L, Chandru H, Boggaram V. Ceramide decreases surfactant protein B gene expression via downregulation of TTF-1 DNA binding activity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L351–L358. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00275.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wispe JR, Clark JC, Warner BB, Fajardo D, Hull WE, Holtzman RB, Whitsett JA. Tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibits expression of pulmonary surfactant protein. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1954–1960. doi: 10.1172/JCI114929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang L, Yan D, Yan C, Du H. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma and ligands inhibit surfactant protein B gene expression in the lung. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36841–36847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SK, Dahmer MK, Quasney MW. MAPK and JAK–STAT signaling pathways are involved in the oxidative stress–induced decrease in expression of surfactant protein genes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30:334–346. doi: 10.1159/000339068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugahara K, Sadohara T, Sugita M, Iyama K, Takiguchi M. Differential expression of CCAAT enhancer binding protein family in rat alveolar epithelial cell proliferation and in acute lung injury. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;297:261–270. doi: 10.1007/s004410051354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alam T, An MR, Papaconstantinou J. Differential expression of three C/EBP isoforms in multiple tissues during the acute phase response. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5021–5024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cassel TN, Nord M. C/EBP transcription factors in the lung epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L773–L781. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg E, Li F, Reisher SR, Wang M, Gonzales LW, Ewing JR, Malek S, Ballard PL, Notarfrancesco K, Shuman H, et al. Members of the C/EBP transcription factor family stimulate expression of the human and rat surfactant protein A (SP-A) genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1575:82–90. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan C, Wu M, Cao J, Tang H, Zhu M, Johnson PF, Gao H. Critical role for CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta in immune complex-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2012;189:1480–1490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bein K, Leight H, Leikauf GD. JUN-CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein complexes inhibit surfactant-associated protein B promoter activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:436–444. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0260OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Reilly MA, Gazdar AF, Morris RE, Whitsett JA. Differential effects of glucocorticoid on expression of surfactant proteins in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;970:194–204. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(88)90179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Reilly MA, Gazdar AF, Clark JC, Pilot-Matias TJ, Wert SE, Hull WM, Whitsett JA. Glucocorticoids regulate surfactant protein synthesis in a pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell line. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:L385–L392. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1989.257.6.L385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L, Lian X, Cowen A, Xu H, Du H, Yan C. Synergy between signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and retinoic acid receptor–alpha in regulation of the surfactant protein B gene in the lung. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1520–1532. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodrum KJ, Poulson-Dunlap J. Cytokine responses to group B streptococci induce nitric oxide production in respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:49–54. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.49-54.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krakauer T. Stimulant-dependent modulation of cytokines and chemokines by airway epithelial cells: cross talk between pulmonary epithelial and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:126–131. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.1.126-131.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutsumi-Ishii Y, Nagaoka I. Modulation of human beta-defensin–2 transcription in pulmonary epithelial cells by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mononuclear phagocytes via proinflammatory cytokine production. J Immunol. 2003;170:4226–4236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das A, Boggaram V. Proteasome dysfunction inhibits surfactant protein gene expression in lung epithelial cells: mechanism of inhibition of SP-B gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L74–L84. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00103.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beutler B, Cerami A. The biology of cachectin/TNF: a primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:625–655. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goya T, Abe M, Shimura H, Torisu M. Characteristics of alveolar macrophages in experimental septic lung. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;52:236–243. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKichan ML, DeFranco AL. Role of ceramide in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–induced signaling: LPS increases ceramide rather than acting as a structural homolog. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1767–1775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xaus J, Comalada M, Valledor AF, Lloberas J, Lopez-Soriano F, Argiles JM, Bogdan C, Celada A. LPS induces apoptosis in macrophages mostly through the autocrine production of TNF-alpha. Blood. 2000;95:3823–3831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pryhuber GS, Church SL, Kroft T, Panchal A, Whitsett JA. 3′-untranslated region of SP-B mRNA mediates inhibitory effects of TPA and TNF-alpha on SP-B expression. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:L16–L24. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.1.L16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitsett JA, Clark JC, Wispe JR, Pryhuber GS. Effects of TNF-alpha and phorbol ester on human surfactant protein and MnSOD gene transcription in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:L688–L693. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.262.6.L688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berhane K, Margana RK, Boggaram V. Characterization of rabbit SP-B promoter region responsive to downregulation by tumor necrosis factor–alpha. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L806–L814. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, Collins PJ, Davis CA, Doyle F, Epstein CB, Frietze S, Harrow J, Kaul R, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irish Critical Care Trials Group. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome in Ireland: a prospective audit of epidemiology and management. Crit Care. 2008;12:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spragg R. Surfactant for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:377–378. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0004ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L379–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livraghi A, Randell SH. Cystic fibrosis and other respiratory diseases of impaired mucus clearance. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:116–129. doi: 10.1080/01926230601060025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guillot L, Medjane S, Le-Barillec K, Balloy V, Danel C, Chignard M, Si-Tahar M. Response of human pulmonary epithelial cells to lipopolysaccharide involves Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)–dependent signaling pathways: evidence for an intracellular compartmentalization of TLR4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2712–2718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keicho N, Elliott WM, Hogg JC, Hayashi S. Adenovirus E1A upregulates interleukin-8 expression induced by endotoxin in pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1046–L1052. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.6.L1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peralta FM, Casale TB. Orientation and presence of epithelium are key to endotoxin-induced neutrophil migration. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:1053–1059. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.11051053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pugin J, Schurer-Maly CC, Leturcq D, Moriarty A, Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2744–2748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Basha MA, Chensue SW, Lynch JP, III, Toews GB, Westwick J, Strieter RM. Interleukin-8 gene expression by a pulmonary epithelial cell line: a model for cytokine networks in the lung. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1945–1953. doi: 10.1172/JCI114928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DiMango E, Zar HJ, Bryan R, Prince A. Diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products stimulate respiratory epithelial cells to produce interleukin-8. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2204–2210. doi: 10.1172/JCI118275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massion PP, Inoue H, Richman-Eisenstat J, Grunberger D, Jorens PG, Housset B, Pittet JF, Wiener-Kronish JP, Nadel JA. Novel Pseudomonas product stimulates interleukin-8 production in airway epithelial cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:26–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI116954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamura H, Yoshimura K, Jaffe HA, Crystal RG. Interleukin-8 gene expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19611–19617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koyama S, Rennard SI, Leikauf GD, Shoji S, Von Essen S, Claassen L, Robbins RA. Endotoxin stimulates bronchial epithelial cells to release chemotactic factors for neutrophils: a potential mechanism for neutrophil recruitment, cytotoxicity, and inhibition of proliferation in bronchial inflammation. J Immunol. 1991;147:4293–4301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koyama S, Sato E, Nomura H, Kubo K, Miura M, Yamashita T, Nagai S, Izumi T. The potential of various lipopolysaccharides to release IL-8 and G-CSF. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L658–L666. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.4.L658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schulz C, Farkas L, Wolf K, Kratzel K, Eissner G, Pfeifer M. Differences in LPS-induced activation of bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) and Type II–like pneumocytes (A-549) Scand J Immunol. 2002;56:294–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hedlund M, Frendeus B, Wachtler C, Hang L, Fischer H, Svanborg C. Type 1 fimbriae deliver an LPS- and TLR4-dependent activation signal to CD14-negative cells. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:542–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naik S, Kelly EJ, Meijer L, Pettersson S, Sanderson IR. Absence of Toll-like receptor 4 explains endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in human intestinal epithelium. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:449–453. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin TR, Mathison JC, Tobias PS, Leturcq DJ, Moriarty AM, Maunder RJ, Ulevitch RJ. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein enhances the responsiveness of alveolar macrophages to bacterial lipopolysaccharide: implications for cytokine production in normal and injured lungs. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:2209–2219. doi: 10.1172/JCI116106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hubbard AK, Timblin CR, Shukla A, Rincon M, Mossman BT. Activation of NF-kappaB–dependent gene expression by silica in lungs of luciferase reporter mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L968–L975. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00327.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berg JT, Lee ST, Thepen T, Lee CY, Tsan MF. Depletion of alveolar macrophages by liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene diphosphonate. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2812–2819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koay MA, Gao X, Washington MK, Parman KS, Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS, Christman JW. Macrophages are necessary for maximal nuclear factor–kappa B activation in response to endotoxin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:572–578. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimakhe S, Heymann D, Guicheux J, Pilet P, Giumelli B, Daculsi G. Polymyxin B inhibits biphasic calcium phosphate degradation induced by lipopolysaccharide-activated human monocytes/macrophages. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;40:336–340. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199805)40:2<336::aid-jbm19>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrett EG, Johnston C, Oberdorster G, Finkelstein JN. Silica-induced chemokine expression in alveolar Type II cells is mediated by TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L1110–L1119. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuquimia OD, Petursdottir DH, Periolo N, Fernandez C. Alveolar epithelial cells are critical in protection of the respiratory tract by secretion of factors able to modulate the activity of pulmonary macrophages and directly control bacterial growth. Infect Immun. 2013;81:381–389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00950-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chuquimia OD, Petursdottir DH, Rahman MJ, Hartl K, Singh M, Fernandez C. The role of alveolar epithelial cells in initiating and shaping pulmonary immune responses: communication between innate and adaptive immune systems. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Damas P, Ledoux D, Nys M, Vrindts Y, De Groote D, Franchimont P, Lamy M. Cytokine serum level during severe sepsis in human IL-6 as a marker of severity. Ann Surg. 1992;215:356–362. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elizur A, Adair-Kirk TL, Kelley DG, Griffin GL, Demello DE, Senior RM. Tumor necrosis factor–alpha from macrophages enhances LPS-induced Clara cell expression of keratinocyte-derived chemokine. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:8–15. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0203OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spight D, Trapnell B, Zhao B, Berclaz P, Shanley TP. Granulocyte–macrophage–colony–stimulating factor–dependent peritoneal macrophage responses determine survival in experimentally induced peritonitis and sepsis in mice. Shock. 2008;30:434–442. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181673543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park WY, Goodman RB, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, Radella F, II, Park DR, Pugin J, Skerrett SJ, Hudson LD, Martin TR. Cytokine balance in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1896–1903. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elias JA, Zitnik RJ. Cytokine–cytokine interactions in the context of cytokine networking. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:365–367. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/7.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haczku A, Atochina EN, Tomer Y, Cao Y, Campbell C, Scanlon ST, Russo SJ, Enhorning G, Beers MF. The late asthmatic response is linked with increased surface tension and reduced surfactant protein B in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L755–L765. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00062.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ladenburger A, Seehase M, Kramer BW, Thomas W, Wirbelauer J, Speer CP, Kunzmann S. Glucocorticoids potentiate IL-6–induced SP-B expression in H441 cells by enhancing the JAK–STAT signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L578–L584. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00055.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ballard PL, Liley HG, Gonzales LW, Odom MW, Ammann AJ, Benson B, White RT, Williams MC. Interferon-gamma and synthesis of surfactant components by cultured human fetal lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1990;2:137–143. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/2.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ito Y, Mason RJ. The effect of interleukin-13 (IL-13) and interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) on expression of surfactant proteins in adult human alveolar Type II cells in vitro. Respir Res. 2010;11:157. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reed JA, Ikegami M, Cianciolo ER, Lu W, Cho PS, Hull W, Jobe AH, Whitsett JA. Aerosolized GM-CSF ameliorates pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in GM-CSF–deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L556–L563. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zsengeller ZK, Reed JA, Bachurski CJ, LeVine AM, Forry-Schaudies S, Hirsch R, Whitsett JA. Adenovirus-mediated granulocyte–macrophage colony–stimulating factor improves lung pathology of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in granulocyte–macrophage colony–stimulating factor–deficient mice. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2101–2109. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.14-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]