Abstract

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a developing approach for chronic pain. The current study was designed to pilot test a brief, widely inclusive, local access format of ACT in a UK primary care setting. Seventy-three participants (68.5% women) were randomized to either ACT or treatment as usual (TAU). Many of the participants were aged 65 years or older (27.6%), were diagnosed with fibromyalgia (30.2%) and depression (40.3%), and had longstanding pain (median = 10 years). Standard clinical outcome measures included disability, depression, physical functioning, emotional functioning, and rated improvement. Process measures included pain-related and general psychological acceptance. The recruitment target was met within 6 months, and 72.9% of those allocated to ACT completed treatment. Immediately post treatment, relative to TAU, participants in ACT demonstrated lower depression and higher ratings of overall improvement. At a 3-month follow-up, again relative to TAU, those in ACT demonstrated lower disability, less depression, and significantly higher pain acceptance; d = .58, .59, and .64, respectively. Analyses based on intention-to-treat and on treatment “completers,” perhaps predictably, revealed more sobering and more encouraging results, respectively. A larger trial of ACT delivered in primary care, in the format employed here, appears feasible with some recommended adjustments in the methods used here (Trial registration: ISRCTN49827391).

Perspective

This article presents a pilot randomized controlled trial of ACT for chronic pain in a primary care setting in the United Kingdom. Both positive clinical outcomes and ways to improve future trials are reported.

Key words: Acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological flexibility, chronic pain, randomized controlled trial, pilot

Broadly, cognitive behavioral approaches to chronic pain, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), have been the predominant psychological treatment for most of the past 30 years.12, 21 These approaches, as the name implies, focus on creating cognitive and behavioral change to help people who have chronic pain to suffer less, function better, and use fewer medical services for their pain. Generally the evidence for CBT for chronic pain is supportive.4, 22 However, the benefits of CBT for chronic pain are not as large and general as they could or should be, including only small effects on disability.37 Some improvement in the CBT approach may be needed.

It is has been suggested that researchers stop testing package treatments that essentially attempt to treat the many problems of chronic pain with many methods in combination.4 There are calls to focus on therapeutic mechanisms, or processes, and moderators, the answers to the questions of how treatment works and for whom.4, 15, 23, 37 There are also calls for approaches that include more comprehensive and integrative theoretical modes.9, 11

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)7 is a form of CBT that may help advance the field of chronic pain management. ACT is not a package-based approach—it is process focused, primarily including a therapeutic process called psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility is the ability to either engage in a behavior pattern or change a behavior pattern depending on one's goals and what the situation affords, in a context of interacting cognitive and direct, noncognitive, influences on behavior.6 Psychological flexibility includes 6 constituent processes: acceptance, present-focused awareness, values, cognitive defusion, self-as-observer, and committed action. ACT is comprehensive, encompassing both healthy and unhealthy psychological processes; integrative; and theoretically based. It focuses on behavior change and on any manipulable influences that can be applied in changing behavior, incorporating influences based in emotional experiences, thoughts, beliefs, and social context. ACT is based on an extension of operant theory that includes a model of cognition and cognitive regulation of behavior, called relational frame theory, and on a philosophy of science called functional contextualism.8

There are now at least 5 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) of ACT related to chronic pain that support its efficacy.2, 27, 34, 35, 36 A wide variety of formats of delivery have been tested but none of these were specifically designed for high-efficiency screening and wide inclusion, for recruitment and delivery in primary care in the UK, over a short time frame, and in a group treatment context. The only ACT-based treatment tested within the UK National Health Service is a high-intensity interdisciplinary model, including more than 90 hours of treatment time, delivered in a specialty hospital setting.20

The purpose of this study was to pilot test a brief version of ACT for chronic pain in a primary care setting, in a small RCT. The treatment tested here was designed to be broadly accessible, with highly inclusive recruitment criteria, and efficient to deliver, including just 4 sessions over 2 weeks.18 An array of potential primary outcome and treatment process variables were collected, including disability, depression, physical functioning, pain, and acceptance, to determine a best primary outcome and process measures for a larger trial of the same treatment. Specific power calculations were not a part of the planning of the study; hence, the primary focus was not on testing predictions for specific, significant outcome effects. The overall objective here was to test key trial methods to plan for a larger study, to gather data for future power calculations, and to consider ways to enhance the treatment or the methods for studying it.

Method

Trial Design

This study included a randomized pilot trial of group treatment for people with chronic pain recruited from general practice. After baseline assessment, participants were randomized to ACT plus treatment-as-usual (TAU) or TAU alone (1:1) based on computer-generated random numbers. The allocation was not concealed from the participants, treatment providers, or the researcher; however, assessment and data entry were conducted blind to allocation. Posttreatment assessment was conducted within 2 weeks of treatment completion (with parallel assessment of those in the TAU group) and at a 3-month follow-up. Sample size was determined on a plan to recruit between 8 and 12 participants for each of 3 ACT groups. A total sample of 60 participants was the target. This study was approved by the regional research ethics committee (reference: 09/H0107/99) and National Health Service Research and Development committee at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Bath.

Recruitment

Participants for this study were recruited from general medical practices in the southwest of England. These practices were recruited through the regional Primary Care Research Network. The practices expressing interest included 119,000 registered patients, and the individual practice list sizes ranged from 5,300 to 13,000. Recruitment was conducted over a period of 2 months in each of 3 separate areas in the southwest primarily during the first quarter of 2012.

Potential participants at each of the practices were identified through record searches applying the inclusion criteria. Inclusion in the study required persistent pain of longer than 3 months' duration, a pain-related consultation with the general practitioner (GP) in the past 6 months, significant pain-related distress and disability, consistent analgesic medications use, ability to communicate in English, and age 18 years or older. Those needing further medical tests or procedures, or with conditions expected by the GP to interfere with participation in the treatment, were excluded.

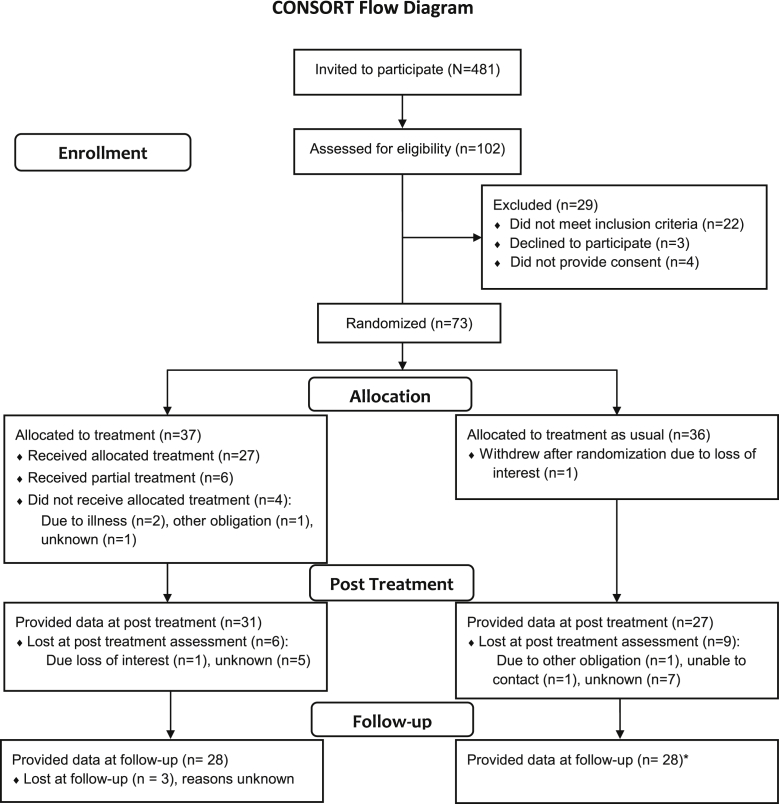

Potential participants meeting eligibility criteria were sent an invitation letter, trial information sheet, consent form, and screening questionnaire by their GPs (N = 481). Participants who wished to take part returned their signed consent forms and the screening questionnaire to the research team by post and were screened for eligibility (n = 102). Twenty-nine potential participants were excluded at this stage, 22 for not meeting criteria. Seven did not provide consent. Seventy-three potential participants were randomized to ACT (n = 37) or treatment as usual (n = 36). A consort diagram is included in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. *One participant in the TAU condition was uncontactable at posttreatment but contactable at follow-up.

Part of the screening process was based on the disability rating portion of the chronic pain grading questionnaire by Von Korff and colleagues.28 Eligible participants needed to rate the level of interference with their daily activities from pain a 4 or higher on a scale from 0 = no interference to 10 = unable to carry on any activities.

Participants

The 73 participants randomized ranged from 23 to 86 years old (mean = 58.0, standard deviation [SD] = 12.8 years), and 27.6% were 65 or older. Most were women (68.5%) and white British (97.3%). Most were married or living with a partner (65.7%); 12.3% were unmarried, 11.0% divorced, 11.0% widowed. They had completed a mean of 12.4 years of education (SD = 4.2). The median pain duration was 10.0 years, range 1.5–50.0 years. The primary locations of pain included low back (37.0%); lower extremity (23.3%); neck (15.1%); all over (13.7%); or other (10.9%). Participants reported wide-ranging and mostly multiple pain-related diagnoses. The most frequently mentioned diagnosis was fibromyalgia (32.0%). Only 9.6% were working full time outside the home. The largest proportion of participants (31.0%) was not working because of pain, and another 8.2% were working part time because of pain. The remaining participants were retired (27.4%); working as homemakers (16.4%); or other (7.4%). At the initial screening phase, all participants completed a measure of medical comorbidities, including 13 health conditions.25 Excluding back pain from the list, 80.9% of participants reported at least 1 of these; 38.2% reported 2 or more; and 17.6% reported 3 or more. The most commonly reported conditions included osteoarthritis (30.6%); depression (40.3%); and hypertension (30.6%).

Treatment Outcome and Process Measures

The baseline, posttreatment, and follow-up measures included the key domains of patient functioning deemed appropriate for chronic pain treatment trials,26 are well validated and standardized, and are frequently used in other treatment studies.3 All measures were administered and returned through the mail. Participants who did not initially return completed measures were contacted once by mail and once by telephone to encourage them to provide their data.

Primary clinical outcome measures included the disability score from the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire,24 depression severity from the Patient Health Questionnaire–9,13 the physical functioning score of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36),33 and a 0 to 10 numerical rating of average pain intensity in the past week.

Secondary outcome measures included the emotional functioning score from the SF-36; a patient global impression of change (PGIC) score, a 7-point numerical rating from 1 = very much improved to 7 = very much worse5; and a question about changes in medication, administered at posttreatment and follow-up only. Health care visits for pain were also tracked through patient report, including GP visits, other visits to physicians, and accident and emergency visits during the previous 3-month period. These items were administered before treatment and at follow-up only.

Treatment process measures included a measure of pain acceptance, the 20-item Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire,19 and a measure of general psychological acceptance, the 7-item Acceptance Action Questionnaire II.1 The Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire assesses the capacity to engage in activities that include pain without struggling with the pain. The Acceptance Action Questionnaire II assesses processes of avoidance or being blocked in functioning from unwanted psychological experiences. When the items are reversed for scoring, they are considered a reflection of general psychological acceptance.

Treatment

The group treatment program was an adaptation of ACT principles and treatment methods for chronic pain.7, 15 The format, setting, and scheduling were designed with local input from people with chronic pain, from GPs and practice nurses, and from health care commissioners, based on group discussion and a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses.32 The treatment includes a combination of methods to promote psychological flexibility, including acceptance, cognitive defusion, and values-based and committed action. It emphasizes experience-based methods, metaphor, and exposure and de-emphasizes lecturing and information-giving. Before the start of treatment, all participants were telephoned by the treatment provider for a very brief introduction and to begin to build some rapport. Treatment was provided by 1 of 2 trained clinical psychologists (L.M.M. and another), each with more than 5 years of experience in treatment for chronic pain and ACT. The format of treatment included 4 sessions, each 4 hours long, delivered 3 sessions one week and 1 session a week later. The content of the treatment was designed so that all of the primary treatment processes were introduced during the first 3 sessions and session 4 was focused on review and further enhancing the processes. Hence, any participant attending at least 3 sessions was considered to have had exposure to all of the key processes. The actual allocated group sizes at the 3 separate locations were the treatment was provided were 12, 12, and 13 participants. All sessions were conducted during afternoon hours in GP practices that were local to the participants. Treatment consistency and fidelity were maintained by use of a treatment manual, and all sessions were audiotaped for later analysis (not reported here).

Treatment as Usual

Participants in the control arm were asked to follow their usual treatments, including any new treatments their GP or their other doctors might wish, during their time in the study. Medication changes and medical visits were then assessed at follow-up.

Analyses

Initial data analyses examined the participants in the 2 treatment conditions for baseline differences on background, treatment outcome, and treatment process variables. Then a series of analyses of covariance were calculated, with the outcome and process variables at posttreatment and follow-up as the dependent variables and the baseline values as covariates. To assess whether there was some influence tied to the 3 varying locations where recruitment and treatment were done, the location of treatment (and therefore treatment groups) was included as a factor to test whether there was such an effect in the data. Following the significance tests, for each of the mean comparisons at posttreatment and follow-up, between-group effect sizes, Cohen's d, were calculated based on posttreatment and follow-up means and pooled SDs. Group outcome differences in the categorical PGIC and medication use variables were examined with chi-square. The clinical outcome and process measures were analyzed in 3 separate ways. First, all available data were submitted to the between-group analyses, regardless of number of treatment sessions attended. Next, an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach to these same analyses was used with imputation of missing data by last value carried forward. Finally, only those who were regarded as receiving a full treatment experience were compared, again, to the control condition. All significance tests were 2-tailed and alpha was set at P < .05, given the pilot nature of this project.

Results

Attendance and Data Adherence

Thirty-three (89.2%) of the 37 participants allocated to the ACT condition attended at least 1 session. Those who did not attend treatment were unable to do so because of illness (n = 2); another obligation (n = 1); or unknown (n = 1). Twenty-seven participants (72.9%) attended 3 or 4 sessions and were regarded as having a complete treatment experience. Eighteen participants (48.6% of those allocated to ACT) attended all 4 sessions of ACT. Thirty-one (83.8% of the 37 participants allocated to ACT) provided data at posttreatment, and 28 (75.7% of those allocated) provided data at follow-up. In the TAU condition, 27 participants (75.0% of those allocated to TAU) provided data conjointly with the completion of the ACT treatment, and 28 (77.7%) provided data at the 3-month follow-up.

Preliminary Analyses

Comparisons using independent groups t-tests of those who provided outcome data showed that the ACT and TAU conditions did not differ on age, education, duration of pain, number of comorbid medical conditions, number of physicians seen in the past due to their pain, or number of times they had seen their GP for pain in the past 3 months, as assessed at baseline. They also did not differ on baseline disability, depression, physical or emotional functioning from the SF-36, acceptance of pain, or psychological acceptance, all P > .05.

Analyses of the group and location effect, across the 14 posttreatment and follow-up analyses involving mean comparisons, revealed 2 significant interactions of the treatment condition effect and this location effect. One of these involved immediate posttreatment disability, F(2, 50) = 3.57, P = .036, and the other involved depression at follow-up, F(2, 48) = 3.31, P = .045. In the first case, inspection of the data showed that 1 of the locations yielded both a relatively high disability score in the TAU group and a relatively low score for the ACT group at posttreatment. The direction of differences between the TAU versus ACT conditions did not differ across locations, nor did the magnitude of posttreatment disability scores across the 3 ACT groups, F(2, 28) = 1.71, P = .20. An analogous situation was observed for the depression result at follow-up but for a separate group/location. Once again, no difference between the ACT groups on depression at follow-up was observed, F(2, 28) = .03, P = .97. Because these were unsystematic, minority issues, and possibly spurious, it was elected to conduct all subsequent analyses with the combined ACT treatment group data.

Posttreatment Outcome Results

Table 1 includes means, SDs, analysis of covariance results, and effect sizes from posttreatment and follow-up. Immediately post treatment, there were significant group differences in favor of ACT for depression but no significant changes for disability, physical functioning as measured by the SF-36, or pain. The effect sizes for depression was small, d = .46. In terms of secondary outcomes, there was a significant posttreatment effect on PGIC, with 53.3% of those in the ACT condition reporting overall improvement whereas in the TAU group the number was 25.0%. There was no significant group difference on emotional functioning from the SF-36. Most patients' pain medication stayed the same in both groups during the treatment interval. One participant in the TAU condition and 3 in the ACT condition reported a decrease in their medication. Six participants in the TAU condition and 4 in the ACT condition reported increases. The difference between groups was not significant.

Table 1.

Results Including All Those Providing Data (n = 58 at Posttreatment, n = 54 at 3-Month Follow-Up)

| Group | Mean (SD) |

Between-Group ANCOVA: F |

Between-Group Effect Size: d |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Follow-Up | Posttreatment | Follow-Up | Posttreatment | Follow-Up | ||

| Primary outcomes measures | ||||||||

| Disability | ACT | 12.23 (4.53) | 9.96 (4.85) | 10.82 (5.55) | 3.16 | 6.10∗ | .32 | .59 |

| TAU | 12.19 (4.84) | 12.58 (6.02) | 14.14 (5.19) | |||||

| Depression | ACT | 11.58 (5.81) | 9.53 (6.84) | 9.95 (7.01) | 5.60∗ | 4.45∗ | .46 | .58 |

| TAU | 12.44 (7.03) | 13.04 (8.31) | 14.08 (6.68) | |||||

| Physical functioning | ACT | 30.35 (22.16) | 31.13 (19.99) | 31.51 (23.28) | <1 | 1.60 | .17 | .39 |

| TAU | 29.18 (27.76) | 27.32 (24.44) | 22.61 (21.19) | |||||

| Pain | ACT | 6.51 (1.92) | 6.45 (1.92) | 6.54 (2.10) | 1.41 | <1 | .44 | .32 |

| TAU | 7.00 (1.64) | 7.27 (1.73) | 7.19 (2.03) | |||||

| Treatment process measures | ||||||||

| Pain acceptance | ACT | 54.87 (14.39) | 64.97 (15.13) | 71.11 (8.86) | 3.60 | 5.83∗ | .26 | .64 |

| TAU | 56.92 (16.14) | 54.92 (17.04) | 64.89 (11.72) | |||||

| Psychological acceptance | ACT | 23.83 (10.77) | 23.60 (11.16) | 23.19 (12.00) | <1 | <1 | .20 | .22 |

| TAU | 24.72 (9.81) | 25.77 (10.75) | 25.55 (9.55) | |||||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| Emotional functioning | ACT | 52.02 (25.43) | 65.55 (16.93) | 64.21 (21.84) | 3.70 | 1.08 | .68 | .20 |

| TAU | 50.15 (23.71) | 50.50 (24.56) | 49.71 (22.11) | |||||

| Percentage Improved | χ2 | |||||||

| Patient rating of change | ACT | 53.33 | 51.90 | 4.43∗ | 3.43 | |||

| TAU | 25.00 | 26.08 | ||||||

| Medication reduction | ACT | 10.3 | 15.38 | <1 | <1 | |||

| TAU | 4.2 | 18.18 | ||||||

Abbreviation: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

NOTE. Disability was measured with the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire, depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9, pain with a 0 to 10 scale of average pain in the past week, physical and emotional functioning with the SF-36, pain acceptance with the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire, psychological acceptance with the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II, rating of change with the 1 to 7 Patient Global Impression of Change scale, and medication reduction with a single self-report item asking whether medication was increased, decreased, or stayed the same. Because of missing data, the actual n in the ACT condition varies from 28 to 31 and in the control condition from 26 to 27, including both posttreatment and follow-up time points.

P < .05. d > .20, small; >.50, medium; >.80, large.

Follow-Up Outcome Results

At the 3-month follow-up, there were significant treatment group differences in outcome in favor of ACT for disability and depression. There were no significant group differences for the measures of physical functioning or pain. The effects at follow-up for disability, d = .59, and depression, d = .58, were medium. There remained roughly twice as many participants in the ACT condition compared to the TAU condition who rated themselves as improved at follow-up; however, this effect marginally missed statistical significance, P = .064. Once again, as at posttreatment, there were no significant group differences in the emotional functioning score from the SF-36 or in pain medication changes.

Treatment Process Results

Contrary to predictions, there were no significant group differences in either acceptance of pain or general psychological acceptance immediately at the completion of the 2-week ACT treatment phase. The difference in acceptance of pain marginally missed significance, P = .063. At follow-up, there remained no significant group difference for general psychological acceptance; however, the group difference in acceptance of pain at this point did reach significance and the effect size was medium, d = .64.

ITT Analyses

Using the last-value-carried-forward method for imputing missing values, ITT analyses on all of those randomized to either ACT or TAU showed a significant effect immediately post treatment for disability, F(1, 70) = 4.43, P < .05, d = .36; depression, F(1, 70) = 5.91, P < .05, d = .46; and marginally significant effects for acceptance of pain, F(1, 70) = 3.91, P = .05, d = .23; and emotional functioning, F(1, 70) = 3.93, P = .05, d = .69. There were no significant effects immediately following treatment for physical functioning, pain, or general psychological acceptance. At follow-up, there was a marginal effect for disability, F(1, 70) = 3.38. P = .07, d = .37, but no significant effects for depression, physical functioning, pain, acceptance of pain, general acceptance, or emotional functioning.

Treatment Completer Analyses

There were 27 participants of those who were allocated to ACT who attended 3 or 4 sessions, 6 who attended 1 or 2 sessions, and 4 who attended none. Three sessions was regarded as the minimum number for being regarded as having completed treatment. Based on analysis of covariance, comparing these treatment completers with the TAU condition, there were significant effects in favor of ACT immediately post treatment for disability, F(1, 49) = 8.39, P < .01, d = .45; depression, F(1, 49) = 8.72, P < .01, d = .53; acceptance of pain, F(1, 49) = 4.59, P < .05, d = .51; and emotional functioning, F(1, 49) = 4.07, P < .05, d = .71. There were no significant effects immediately post treatment for physical functioning, pain, or general acceptance. At follow-up, there were significant effects for disability, F(1, 51) = 5.43, P < .05, d = .55; depression, F(1, 50) = 5.82, P < .05, d = .59; and acceptance of pain, F(1, 48) = 4.87, P < .05, d = .59. There were no significant effects at follow-up for physical functioning, pain, general acceptance, or emotional functioning.

In the completer analyses, as in the analyses of all those providing data, global ratings of improvement immediately following treatment again significantly favored the ACT condition, χ2(1, n = 48) = 4.87, P < .05. Global ratings of improvement at follow-up did not show a significant difference, P = .067.

Additional Post Hoc Analyses

In general, there was not a high rate of health care use in the treatment groups during 3-month period before the start of treatment and at follow-up. The modal number of GP visits was 1 and the modal number of other doctor and accident and emergency visits was zero in both groups at both time points. At follow-up, there were just 20.4% of participants who saw their GP more than 2 times. Eight of these 11 people (72.5%) reported 3 or 4 visits, 1 reported 5 visits, and 2 reported weekly visits, a pattern that had carried on from pretreatment. There were no significant follow-up differences between the treatment conditions in GP visits, other doctor visits, accident and emergency visits, or total visits during the 3-month follow-up interval, all t < 1.67, all P > .10.

Discussion

The current study was developed as a pilot RCT of ACT in comparison to treatment as usual for chronic pain in a general practice setting in the United Kingdom. The setting, recruitment strategy, and the brief treatment format had not been previously tested and the present study was designed to see if an RCT could be conducted with these elements. In this trial, we demonstrated successful recruitment of the targeted number of participants, greater than 60, in a short period of 2 months at each of 3 locations; 73% in the ACT condition were regarded as having received the complete treatment, and more than 75% of the total sample randomized were retained at follow-up.

Power calculations were not done nor were formal predictions of significant treatment effects made during the design of this study. With this proviso in mind the ACT condition did produce a number of significant treatment effects compared to the TAU condition, on depression and patient-rated improvement at posttreatment and on disability, depression, and pain acceptance at the 3-month follow-up. Effect sizes for the significant effects were small for depression immediately post treatment, and medium for disability, depression, and acceptance of pain at follow-up.

Analyses done on an ITT basis or focused only on those who were regarded as completing treatment provide distinctly differing views of the trial results. The ITT analyses showed significant effects in favor of ACT for disability and depression but only nonsignificant marginal effects for acceptance of pain and emotional functioning. Only a marginal nonsignificant effect for disability remained at follow-up. Analyses excluding participants who missed 2 or more of the 4 sessions, so-called completer analyses, showed more positive results, including significantly better results for the ACT condition in comparison to the TAU condition on disability, depression, pain acceptance, and emotional functioning at posttreatment, and disability, depression, and pain acceptance at follow-up. Significant between-group effect sizes were small to medium at posttreatment and medium at follow-up. It should be clarified that the sample size of this RCT is small compared to trials designed to produce more definitive results.14 These results ought to be seen as preliminary. The positive results from the completer analyses compared to ITT particularly call for further investigation of the variables that identify who completes and who does not complete treatment, how to improve engagement, and whether it is possible to identify those who achieve poor results regardless.

There are a number of other preliminary RCTs of ACT for chronic pain,2, 27, 35, 36 and at least 1 larger trial comparing ACT to more traditional CBT (N = 114).34 There are also nonrandomized, partly controlled, or pilot studies,10, 20, 31 a reanalysis of treatment outcome focused on older adults,17 and several effectiveness studies,16, 29 including 1 showing good outcomes at 3 years posttreatment.30 The present study is consistent with the previous ones in providing support for ACT and in providing a basis for more ambitious or more focused studies. It differed from the earlier studies in that it was conducted exclusively within primary care in the United Kingdom, with very liberal inclusion criteria, with no face-to-face assessment or screening, and unlike some of the earlier RCTs it included group delivery. It was also significantly briefer in the number of sessions and in total treatment hours compared with some previous group-based treatments, particularly those conducted in the United Kingdom.16, 20

It may appear unnecessary to conduct or present more preliminary trials of ACT. However, the planning and application for funding the current study began in 2008, a time when there were significantly fewer publishes studies. Certainly the unique features in the design of the current treatment represent, including its base in UK primary care, its 4-session format, and its minimal screening, provide a way to examine the robustness and generality of the treatment model.

There are some inconsistencies in our current results that may provide a basis for improvement in later trials. Unexpectedly, participants in the TAU condition demonstrated increases in disability and depression, especially at follow-up. These changes contribute to the observed between-group effects on these outcomes. Perhaps even more unexpectedly, they also demonstrated a remarkable increase in acceptance of pain, a change that reduced the between-group effect. The posttreatment effect on acceptance of pain was small. This is inconsistent with our previous studies, where effects on acceptance of pain were large and among the largest achieved in comparison to other outcome and process variables.16, 29 Likewise, we produced only small nonsignificant effects on our measure of general psychological acceptance, among the smallest of all those observed, and small or inconsistent effects on the physical and emotional functioning scales of the SF-36. In future studies, with treatment formats similar to the one used here, treatment providers may need to intensify the methods applied to pain-related and psychological acceptance or devote more time to these.

The sample of participants encountered in this study was more chronic, more complex, and more diverse than expected. There were highly disabled participants who had failed previous psychological treatments with a higher intensity than the treatment provided here. It is clear that the SF-36 scales in particular produced highly variable scores. There were some participants with extremely limited mobility—2 participants attended in wheelchairs. In the future, it may improve the outcome of trials of a similar treatment format to narrow the range of disability among the participants, add a physical rehabilitation piece to the psychology treatment methods for those with higher physical disability, and perhaps to screen out those who had already failed higher-intensity treatments of a similar type. A screening visit with a treatment provider, rather than solely paper-based screening as done here, could certainly help to screen out some cases where there is a high likelihood that the treatment will not meet their needs. This is normal in actual clinical practice. Finally, there were engagement challenges, particularly in the 27% of participants in the ACT condition who did not participate in a full treatment experience. This trial was not resourced to address engagement as is sometimes done in specialty treatment centers, such as with additional one-to-one sessions with some participants. On the other hand, this treatment was designed for high accessibility and for efficient delivery, and this was achieved, albeit with the result that some individuals may have received less than optimal results.

In previous results from this same sample, it was shown that participants in the ACT groups found the treatment credible and found participating in the study acceptable.18 It was also found that some participants experienced greater pain or fatigue, or found the sessions too lengthy. Even though this was not the majority, it was nonetheless a significant minority. This is somewhat a conundrum as ACT actually operates by including unwanted psychological experiences in treatment delivery so that the ways that these can create barriers to daily functioning can be examined directly and so that new patterns of behavior can be shaped and rehearsed in the context of treatment. Certainly the group delivery mode and the limited one-to-one relationship between the therapist and each participant place some limits on how a treatment provider can reverse avoidance patterns that occur in treatment sessions, and seek to loosen the grip of thoughts and beliefs that participants hold tightly. Finally, even though we attempted to ease the burden of participation by designing a 4-session treatment, the 4-hour session length and the total treatment time remain a considerable burden and certainly will not suit some people's circumstances. These are challenges for continuing treatment development.

The present study obviously has a number of limitations both as a pilot and especially as a test of ACT. First, it is no more than a pilot for a pragmatic trial, as there was no active treatment comparison condition. This type of design does not allow specific statements about the efficacy of ACT. The region of the country and the specific GP practices involved represent a selected sample, and it is not clear that similar results will be obtained in other regions and other practices. The clinical outcome results for disability and depression were not echoed in effects on physical and emotional functioning. Even given the limited statistical power here, this means that either the treatment is failing in some specific way or the SF-36 is not sensitive to specific treatment results. We did learn that some of the participants struggled with the wording in some of the items of the SF-36, particularly the distance implied by a “block,” a concept not commonly used in the United Kingdom, and the notion of “full of pep.” In the future, a change in this measure or in the treatment is advisable. Finally, as a small RCT without registered trial unit support, it was not powered for a definitive result and certainly there are potential sources of bias that are uncontrolled. Although data were gathered and entered blind and analyses were supervised by a statistician (G.J.T.), they were not all conducted blind to treatment condition, for example.

In summary, further larger-scale trials of ACT for chronic pain, such as in primary care and in the United Kingdom, appear feasible and are recommended, with a few adjustments from the methods used here. Significant treatment effects for disability, depression, and pain acceptance may be achievable, including perhaps medium-sized effects after a short follow-up interval of 3 months. We hypothesize that a number of factors may have reduced treatment impact, and perhaps greater attention to these can be incorporated in future trials. It seems possible, based on comparisons with previous results, that 1 or more of the following modifications could improve outcomes: intensifying the methods to produce results on acceptance, especially general psychological acceptance; recruiting a more homogeneous sample in their current functioning; excluding those who failed previous treatments; including a face-to-face assessment prior to the start of treatment; including a physical exercise component; and/or allowing one-to-one sessions for patients with engagement difficulties.

Acknowledgments

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0808-16156). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors thank Dr Miles Thompson for his help during treatment delivery on this project.

Footnotes

This research was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme.

The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Bond F.W., Hayes S.C., Baer R.A., Carpenter K.C., Guenole N., Orcutt H.K., Waltz T., Zettle R.D. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behav Ther. 2011;42:676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahl J., Wilson K.G., Nilsson A. Acceptance and commitment therapy and the treatment of persons at risk for long-term disability resulting from stress and pain symptoms: A preliminary randomized trial. Behav Ther. 2004;35:785–801. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dworkin R.H., Turk D.C., Farrar J.T., Haythornthwaite J.A., Jensen M.P., Katz N.P., Kerns R.D., Stucki G., Allen R.R., Bellamy N., Carr D.B., Chandler J., Cowan P., Dionne R., Galer B.S., Hertz S., Jadad A.R., Kramer L.D., Manning D.C., Martin S., McCormick C.G., McDermott M.P., McGrath P., Quessy S., Rappaport B.A., Robbins W., Robinson J.P., Rothmar M., Royal M.A., Simon L., Stauffer J.W., Stein W., Tollett J., Wernicke J., Witter J. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eccleston C., Williams A.C., Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guy W. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1976. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (DHEW Publication No. ADM 76-338) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes S.C., Luoma J.B., Bond F.W., Masuda A., Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes S.C., Strosahl K., Wilson K.G. Guildford Press; New York: 1999. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes S.C., Strosahl K.D., Wilson K.G. Guilford Press; London: 2012. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen M.P. Psychosocial approaches to pain management: An organizational framework. Pain. 2011;152:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson M., Foster M., Shennan J., Starkey N.J., Johnson A. The effectiveness of an acceptance and commitment therapy self-help intervention for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:393–402. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181cf59ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keefe F.J., Rumble M.E., Scipio C.D., Giordano L.A., Perri L.M. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: Current state of the science. J Pain. 2004;5:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerns Rd, Sellinger J., Goodin B.R. Psychological treatment of chronic pain. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:411–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-090310-120430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamb S.E., Lall R., Hansen Z., Castelnuovo E., Withers E.J., Nichols V., Griffiths F., Potter R., Szczepura A., Underwood M. A multicentred randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based cognitive behavioural programme for low back pain. The Back Skills Training (BeST) trial. Health Technol Asssess. 2010;14:1–253. doi: 10.3310/hta14410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCracken L.M. IASP Press; Seattle, WA: 2005. Contextual Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCracken L.M., Gutiérrez-Martínez O. Processes of change in psychological flexibility in an interdisciplinary group-based treatment for chronic pain based on acceptance and commitment therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCracken L.M., Jones R. Treatment for chronic pain for adults in the seventh and eighth decades of life: A preliminary study of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) Pain Med. 2012;13:861–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCracken L.M., Sato A., Wainwright D., House W., Taylor G.J. A feasibility study of brief group-based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic pain in general practice: Recruitment, attendance, and patient views. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1463423613000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCracken L.M., Vowles K.E., Eccleston C. Acceptance of chronic pain: Component analysis and a revised assessment method. Pain. 2004;107:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCracken L.M., Vowles K.E., Eccleston C. Acceptance-based treatment for persons with complex longstanding chronic pain: A preliminary analysis of treatment outcome in comparison to a waiting phase. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morley S. Efficacy and effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic pain: Progress and some challenges. Pain. 2011;152:S99–S106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morley S., Eccleston C., Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morley S., Keefe F.J. Getting a handle on process and change in CBT for chronic pain. Pain. 2007;127:197–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roland M., Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I. Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangha O., Stucki G., Liang M.H., Fossel A.H., Katz J.N. The self-administered comorbidity questionnaire: A new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum (Arthritis Care Res) 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turk D.C., Dworkin R.H., Allen R.R., Bellamy N., Brandenburgh N., Car D.B., Cleeland C., Dionne R., Farrar J.T., Galer B.S., Hewitt D.J., Jadad A., Katz N.P., Kramer L.D., Manning D.C., McCormick C.G., McDermott M., McGrath P., Quessy S., Rappaport B.A., Robinson J.P., Royal M.A., Simon L., Stauffer J.W., Stein W., Tollett J., Witter J. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2003;106:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorsell J., Finnes A., Dahl J., Lundgren T., Gybrant M., Gordh T., Buhrman M. A comparative study of 2 manual-based self-help interventions, acceptance and commitment therapy and applied relaxation, for persons with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:716–723. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318219a933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Korff M., Ormel J., Keefe F.J., Dworkin S.F. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vowles K.E., McCracken L.M. Acceptance and values-based action in chronic pain: A study of treatment effectiveness and process. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:397–407. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vowles K.E., McCracken L.M., Zhao-O'Brien J. Acceptance and values-based action in chronic pain: A three year follow-up analysis of treatment effectiveness and process. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vowles K.E., Wetherell J.L., Sorrett J.T. Targetting acceptance, mindfulness, and values-based action in chronic pain: Findings of two preliminary trials of an outpatient group-based intervention. Cogn Behav Prac. 2009;16:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wainwright D., Boichat C., McCracken L. Using the nominal group technique to engage people with chronic pain in health service development. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hpm.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware J.E., Sherbourne C.D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wetherell J.L., Afari N., Rutledge T., Sorrell J.T., Stoddard J.A., Petkus A.J., Solomon B.C., Lehman D.H., Liu L., Lang A.J., Atkinson J.H. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:2098–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wicksell R.K., Ahlqvist J., Bring A., Melin L., Olsson G. Can exposure and acceptance strategies improve functioning and life satisfaction in people with chronic pain and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD)? A randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;37:169–182. doi: 10.1080/16506070802078970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wicksell R.K., Kemani M., Jensen K., Kosek E., Kadetoff D., Sorjonen K., Ingvar M., Olsson G.L. Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2012;17:599–611. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams A.C.D.C., Eccleston C., Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]