Abstract

Bacteria have been widely reported to use quorum sensing (QS) systems, which employ small diffusible metabolites to coordinate gene expression in a population density dependent manner. In Proteobacteria, the most commonly described QS signaling molecules are N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs). Recent studies suggest that members of the abundant marine Roseobacter lineage possess AHL-based QS systems and are environmentally relevant models for relating QS to ecological success. As reviewed here, these studies suggest that the roles of QS in roseobacters are varied and complex. An analysis of the 43 publically available Roseobacter genomes shows conservation of QS protein sequences and overall gene topologies, providing support for the hypothesis that QS is a conserved and widespread trait in the clade.

Keywords: quorum sensing, Roseobacter, marine bacteria, biogeochemical cycles, acyl-homoserine lactones

Introduction

When acting as coordinated communities, bacterial populations are able to influence their local environment in manners that are unachievable by individual cells. It has been widely reported that phylogentically diverse bacteria use genetic regulatory systems, known as quorum sensing (QS) systems, to coordinate gene expression in a population density dependent manner (e.g., Fuqua et al., 2001; Pappas et al., 2004; Case et al., 2008; Ng and Bassler, 2009). Among other things, QS is hypothesized to facilitate maximal access to available nutrients through the use of exoenzymes (Vetter et al., 1998; Schimel and Weintraub, 2003), the colonization of desirable niches (Nadell et al., 2008, 2009), and competitive advantages against other organisms (Folcher et al., 2001; Chin-a-Woeng et al., 2003; Barnard et al., 2007). The chemical mediators of QS are often small molecular weight diffusible molecules (Fuqua et al., 2001; Churchill and Chen, 2011). A well-characterized type of QS uses N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) and appears exclusive to Proteobacteria (Case et al., 2008). Canonical AHL-QS systems produce and respond to AHLs using two proteins that mediate signal production and response, LuxI and LuxR-like proteins, respectively (Nealson et al., 1970; Ruby, 1996). The genes encoding these two proteins are often located adjacent to one another on the chromosome (Fuqua et al., 1996; Churchill and Chen, 2011; Gelencsér et al., 2012). LuxI-like proteins synthesize AHLs by cyclizing S-adenosyl methionine into a lactone ring and the addition of an acylated carbon chain from fatty acid biosynthesis pathways (Schaefer et al., 1996). Chain length and modification at the third carbon (either -H, -OH, or -O) allow for species or group specificity (Schaefer et al., 1996; Fuqua et al., 2001). LuxR-like proteins are response regulators that mediate the expression of genes required for communal behavior in response to intracellular concentrations of cognate AHLs (Fuqua and Winans, 1994; Fuqua et al., 1996). Activated LuxR proteins often upregulate luxI transcription to enhance the rate of AHL synthesis, increasing AHL concentrations, and also modulate the expression of other genes (Fuqua et al., 1996, 2001; Case et al., 2008).

AHL-based QS is common in Proteobacteria, which are abundant in coastal marine systems (Dang and Lovell, 2002; Waters and Bassler, 2005; Ng and Bassler, 2009). One of the most abundant and biogeochemically active groups of marine a α-proteobacteria is the Roseobacter clade (Gonzalez and Moran, 1997; Buchan et al., 2005). Roseobacters can comprise up to 30% of the total 16S rRNA genes in coastal environments and up to 15% in the open ocean (Buchan et al., 2005; Wagner-Dobler and Bibel, 2006). In coastal salt marshes, roseobacters are the primary colonizers of surfaces and mediate a wide range of biogeochemically relevant processes, including mineralization of plant-derived compounds and transformations of reduced inorganic and organic sulfur compounds (Gonzalez and Moran, 1997; Dang and Lovell, 2000; Buchan et al., 2005; Dang et al., 2008). Here, we describe some of the most compelling recent research that focuses on QS in the Roseobacter clade, provide a genomic perspective of QS systems in roseobacters, and highlight areas for further investigation.

Roseobacters and quorum sensing

QS was first reported in roseobacters associated with marine snow and hypothesized to contribute to the ability of group members to colonize particulate matter in the ocean (Gram et al., 2002). Subsequent studies further demonstrated that roseobacters are prolific colonizers of a variety of marine surfaces, both inert and living, and the contribution of QS to this ability and other physiologies is of growing interest (Dang and Lovell, 2002; Berger et al., 2011; Zan et al., 2012). Characterized Roseobacter isolates produce diverse AHL structures with acyl chains ranging from eight to eighteen carbons in length that display varying degrees of saturation as well as all three possible oxidation states (-H, -OH, or -O) at the third carbon (for structures see Gram et al., 2002; Wagner-Dobler et al., 2005; Cicirelli et al., 2008; Mohamed et al., 2008; Thiel et al., 2009; Berger et al., 2011; Zan et al., 2012). The production of AHLs has been detected by LuxR-LacZ fusion bioreporters and mass spectrometry for several isolates (Gram et al., 2002; Wagner-Dobler et al., 2005; Martens et al., 2007; Thiel et al., 2009; Berger et al., 2011; Zan et al., 2012). Of the 43 publicly available Roseobacter genomes, only five lack annotated luxI homologs: Oceanicola batsensis HTCC2597, Oceanicola sp. S124, Pelagibaca bermudensis HTCC2601, Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2255, and Ruegeria sp. TM1040. All except HTCC2255, however, have luxR homologs (Table A2). Thus far, experimental studies of QS have primarily focused on isolated representatives of the Ruegeria-Phaeobacter branch of the Roseobacter clade, with the exception of the description of a diunsaturated long chain AHL produced by Jannaschia helgolandensis (Thiel et al., 2009), a survey of 31 AHL producing isolates (Wagner-Dobler et al., 2005), and a recent analysis of QS in Dinoroseobacter shibae, where QS was shown to control motility, expression of a type IV secretion system, and whether the cells divided by binary fission or budding (Patzelt et al., 2013).

Culture-based studies of bacterial symbionts of marine sponges suggest that roseobacters are the primary producers of AHLs in these systems (Taylor et al., 2004). A model for sponge-associated roseobacters has been established using Ruegeria sp. KLH11 (Zan et al., 2011). Studies with this strain have been informative in providing insight into the contributions of QS to host-bacterial interactions. KLH11 contains two sets of luxRI homologs, designated ssaRI (RKLH11_1559 and RKLH11_2275) and ssbRI (RKLH11_1933 and RKLH11_260), and a recently discovered orphan luxI, designated sscI, that is not annotated in the publically available KLH11 genome. While orphan luxI have not been widely described in the literature, they are best described as luxI homologs that are not immediately adjacent to a corresponding luxR homolog on the chromosome. It has been proposed that sscI is a recent duplication of ssbI (Zan et al., 2012). Heterologous expression of SsaI, SsbI, and SscI in Escherichia coli showed that they predominantly produce long chain saturated and unsaturated AHLs (C12-16). More specifically, SsaI produces 3O-AHL variants whereas SsbI and SscI produce 3OH-AHLs (Zan et al., 2012). The modification at the third carbon has been shown to affect the binding affinity of signaling molecules to LuxR homologs, and may allow KLH11 to finely tune its metabolism to cellular density and AHL diversity (Koch et al., 2005). KLH11 mutants deficient in QS display impaired motility, which corresponds to decreased transcription of genes encoding flagella biosynthesis machinery. The QS and motility impaired mutants form drastically thicker biofilms, suggesting when motility or QS is retarded, biofilm formation is increased (Zan et al., 2012). This may also suggest that biofilm formation may not be directly controlled by QS, but that when quorum is achieved, motility and biofilm dispersion are induced. Recent work has shown a phosphorelay system that controls motility in KLH11 is induced by QS (Zan et al., 2013). A similar phenotype has been observed in other roseobacters, and this trend may extend across the Ruegeria-Phaeobacter subgroup (Bruhn et al., 2006; Dobretsov et al., 2007).

QS-mediated physiologies have been implicated in one of the few examples of roseobacters demonstrating antagonistic behavior toward a eukaryotic host. Nautella (formerly Ruegeria) sp. R11 readily colonizes the macroalga Delisea pulchra resulting in bleaching and subsequent death (Case et al., 2011; Fernandes et al., 2011). To combat infection, D. pulchra produces halogenated furanones, which have been shown to block AHL-based QS systems in many bacterial species. Active synthesis of furanones prevents macroalgal colonization by epiphytic bacteria, including Nautella sp. R11. However, in the absence of halogen substrates required for furanone biosynthesis, colonization occurs rapidly (Manefield et al., 1999; Hentzer et al., 2002; Defoirdt et al., 2007). Further, it appears furanones may be effective against other potentially pathogenic Ruegeria spp. (Zhong et al., 2003).

QS is closely connected to antimicrobial production in several roseobacters. In Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I, the regulatory controls dictating the production of the antimicrobial compound indigoidine are complex and include QS. Indigoidine production confers a competitive advantage to Y4I when grown in co-culture with Vibrio fischeri. Transposon insertions in either of two separate luxRI-like systems leads to an inability of Y4I mutants to produce wildtype levels of indigoidine and an inability to inhibit the growth of V. fischeri. This indicates a role for both QS systems in the synthesis of indigoidine (Cude et al., 2012). The presence of multiple QS systems in the genomes of many roseobacters suggests multi-layered control is a common feature to regulate energy intensive processes, including secondary metabolite production.

Tropodithietic acid (TDA) is a broad spectrum antimicrobial produced by multiple roseobacters in response to QS (Bruhn et al., 2005; Porsby et al., 2008; Berger et al., 2011). Genome analyses of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis strains isolated from geographically distant locations suggest they are capable of producing both AHLs and TDA (Thole et al., 2012). P. gallaeciensis 2.10 has been suggested to produce TDA in response to AHLs while colonizing the marine alga Ulva australis, thus protecting the alga from bacterial, fungal, and larval pathogens (Rao et al., 2007). A closely related strain, P. gallaeciensis DSM17395, which has also been shown to colonize U. australis (Thole et al., 2012), produces N-3-hydroxydecanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OHC10-HSL) using the LuxI homolog PgaI. 3OHC10-HSL activates the adjacent regulator, PgaR, in a concentration dependent manner, which leads to the upregulation of a TDA biosynthetic operon (Berger et al., 2011). Interestingly, in a ΔpgaI strain of DSM17395, addition of exogenous TDA is sufficient to upregulate TDA biosynthesis machinery, suggesting that regulation of TDA biosynthesis may involve multiple signals in some strains (Berger et al., 2011). The dual role of TDA as an autoinducer and an antimicrobial has also been demonstrated in Ruegeria sp. TM1040, which lacks AHL-based QS (Geng and Belas, 2010). Collectively, these data show that in addition to AHLs, roseobacters use novel autoinducers. In fact, recent investigations into novel non-fatty acyl-HSLs have shown that at least one Roseobacter, Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3, is capable of producing p-coumaroyl-homoserine lactone when grown in the presence of the aromatic lignin breakdown product p-coumaric acid (Schaefer et al., 2008). This discovery raises the possibility that many novel signaling molecules could be produced by roseobacters in response to available local substrates, specifically plant-derived aromatics which are primary growth substrates for roseobacters (Buchan et al., 2000; Gulvik and Buchan, 2013). The production of specific signaling molecules in response to exogenously supplied substrates suggest a single signal may convey information about both population density and environmental conditions (i.e., availability of a substrate that serves as both a source of organic nutrients and a colonizable surface), which would dictate a specific set of behaviors.

Quorum sensing gene homology and topology

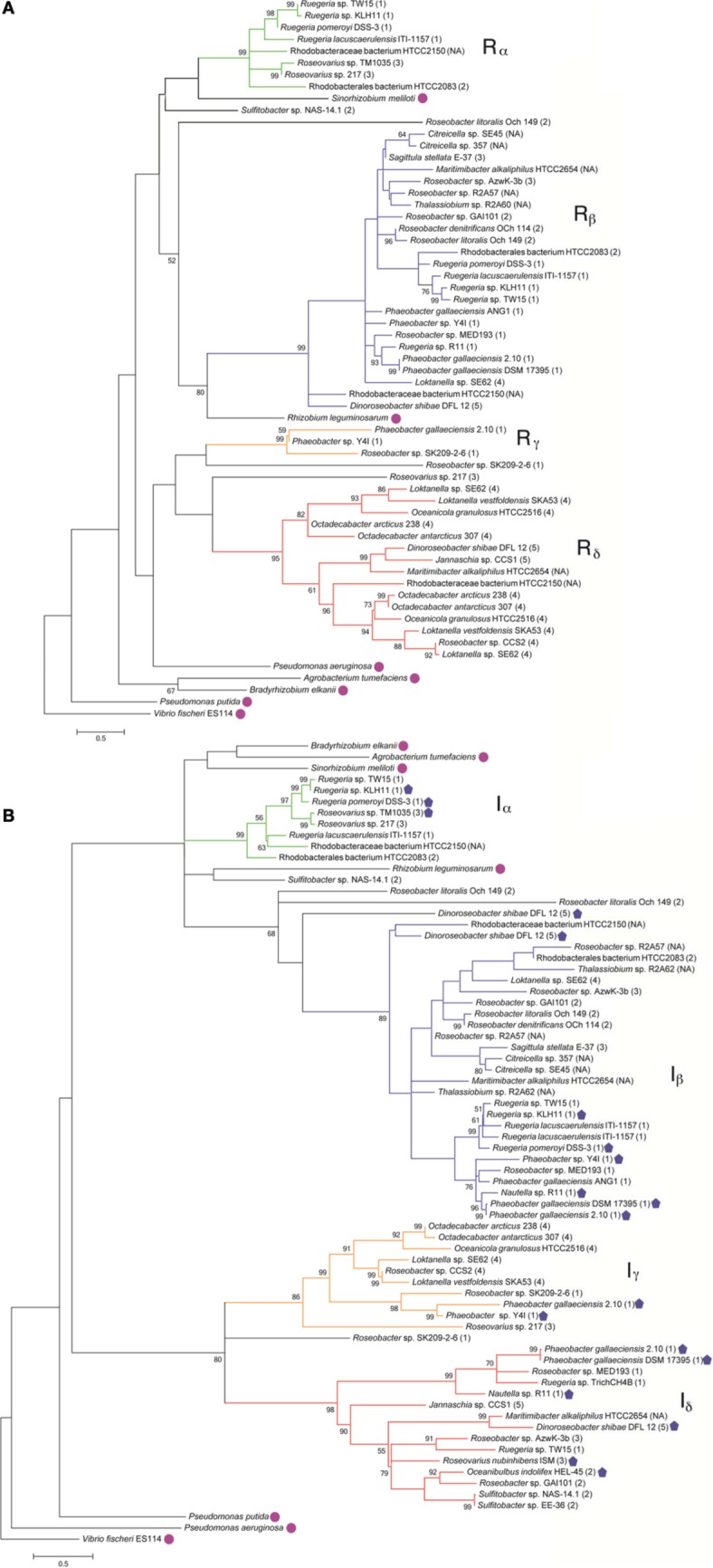

To understand the relatedness of AHL-based QS systems in roseobacters, we performed a phylogenetic reconstruction of the LuxI- and their neighboring LuxR-like sequences in 38 Roseobacter genomes. As solo LuxR homologs have been found to bind a variety of ligands, including non-AHL molecules from eukaryotic organisms (Pappas et al., 2004; Subramoni and Venturi, 2009), it is difficult to infer their contribution in AHL-based QS. Thus, luxR genes that are not adjacent to luxI genes were not included in this analysis, but they are listed in Table A2. Likely a result of the close relatedness of clade members and instances of horizontal gene transfer (HGT), many of the LuxR- and LuxI-like proteins analyzed show high sequence similarity and can be grouped together (Figures 1A,B). Our phylogenetic trees suggests there are four LuxR-like (designated Rα, Rβ, Rγ, and Rδ) and four LuxI-like protein types (designated Iα, Iβ, Iγ, and Iδ) found in most sequenced roseobacters, though more sequence variants may be discovered as more genome sequences become available.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees of Roseobacter LuxR- (A) and LuxI-like (B) deduced amino acid sequences (see Appendix for details). Strain designations are shown and gene locus tags of the corresponding gene sequences can be found in Table A1. The scale bar represents the substitutions per sequence position. The Roseobacter clade number is represented in parentheses after the organism name and follows the classification system identified in Newton et al., 2010. Proposed designations of LuxR and LuxI subgroups in roseobacters are indicated by Greek character subscript and color. Bootstrap values <50% (from 1000 iterations) are shown at branch nodes. Sequences designated with a closed pentagon indicate organisms that have been shown experimentally, by either bioreporters or mass spectrometry, to produce AHLs (Wagner-Dobler et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2006; Bruhn et al., 2007; Berger et al., 2011; Case et al., 2011; Zan et al., 2012). Sequences designated with a circle are non-roseobacters.

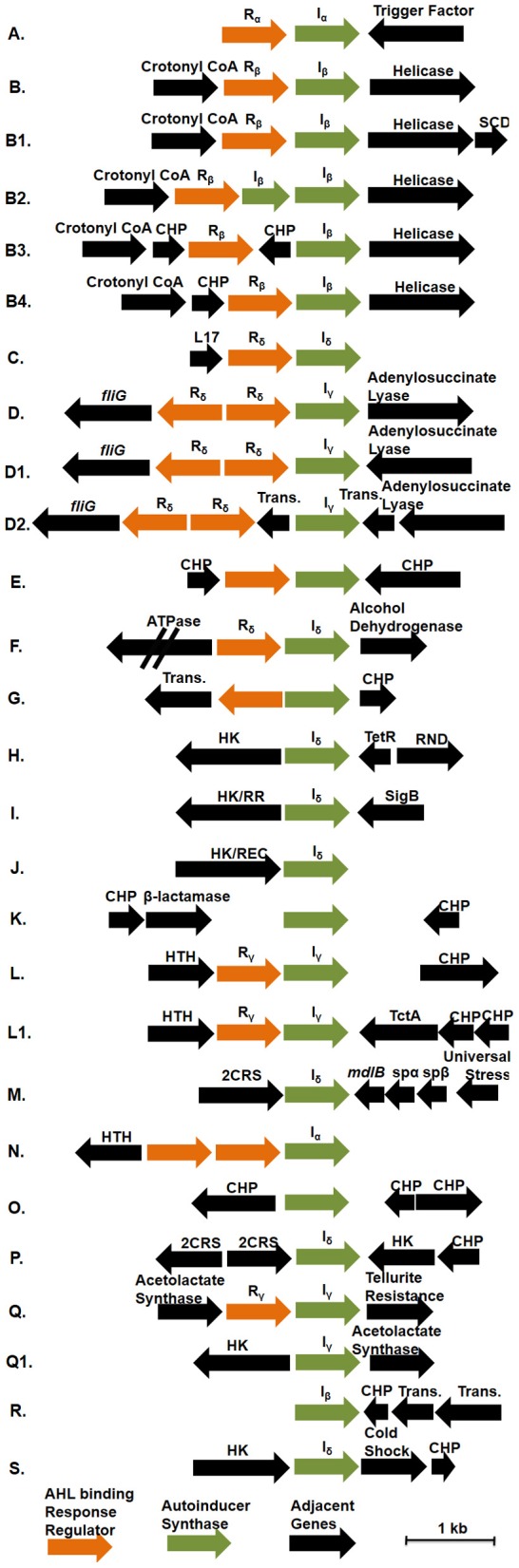

Genome analysis demonstrates that multiple conserved QS gene topologies are present within sequenced roseobacters, allowing for classification by sequence similarity and gene orientation (Figure 2 and Table A1). The most conserved gene topologies are the A and B groups, of which 28 different Roseobacter genomes contain one of the orientations, and three Ruegeria genomes contain both. Genomes that contain the A topology have highly similar LuxI and LuxR sequences (>63 and >70% similarity, respectively) and its presence in three different roseobacter subclades (defined in Newton et al., 2010) may be suggestive of HGT (Figures 1A,B). Genomes with topology A share a Trigger Factor (TF) encoding gene downstream from luxRI (Figure 2). The location of this TF is conserved in seven genomes. Though the function has not been examined in roseobacters, in Vibrio cholera, TFs play a role in the folding and secretion of proteins (Ludlam et al., 2004). The LuxI and LuxR of the A topology have been designated Iα and Rα, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The gene orientation of all putative luxRI operons in available Roseobacter genomes. Green arrows represent AHL synthase encoding genes (luxI), orange arrows represent AHL binding response regulators (luxR), and black arrows represent adjacent genes. Abbreviations used: Crotonyl CoA, Crotonyl CoA reductase; HK, histidine kinase; HK/RR, hybrid histidine kinase/response regulator; HK/REC, histidine kinase with REC domain; CHP, conserved hypothetical protein; RND, RND multidrug efflux pump; Sig B, sigma B factor; SCD, short chain dehydrogenase; Trans., transposase; L17, L17 component of the 50S ribosomal protein; 2CRS, two-component regulatory system; TctA, TctA family transmembrane transporter; mdlB, mandelate dehydrogenase mdlB; spαβ, α and β subunits of sulfopyruvate decarboxylase. Rx and Ix designations above the response regulators and AHL synthases indicate their corresponding phylogentic subgroupings in Figures 1A,B, respectively. Those without Rx and Ix designations indicate unique sequences not found in the conserved groupings. The corresponding genomes that contain these topologies can be found in Table A1.

The B topology is the most prevalent among the sequenced roseobacters and is found in four variations in 24 genomes (Table A1). Like the A topology, the LuxI and LuxR protein sequences are highly similar (>73%) between the organisms that contain the B topology. This topology is found in members of all five Roseobacter subclades identified by Newton et al. (2010) (Figures 1A,B). The LuxI and LuxR of the B topology have been labeled Iβ and Rβ, respectively (Figure 2). The conserved regions of the B topology include genes encoding a crotonyl-CoA reductase preceding luxRI and a putative ATP-dependent helicase following luxRI. In some organisms, crotonyl-CoA reductase interconverts unsaturated crotonyl-CoA to saturated butyryl-CoA as a precursor to fatty acid biosynthesis (Wallace et al., 1995). The helicase may be involved in DNA repair, protein degradation, or gene regulation (Snider et al., 2008). The B1 subgroup is the most abundant orientation within the B group, and contains a short-chain dehydrogenase following the helicase. This gene orientation is conserved in 14 Roseobacter genomes. Short-chain dehydrogenases are a large family of proteins that modify carbon chains of many substrates (Joernvall et al., 1995). The protein encoded by this gene may function to modify AHL biosynthesis substrates before or after AHL production.

Variations of the D topology are found in six Roseobacter genomes, all belonging to members of the Roseobacter subclade 4 (Figures 1A,B). These LuxI and LuxR proteins share >52 and >64% sequence similarity, respectively. The LuxI and LuxR of the D topology have been designated Iγ and Rδ (Figure 2). This topology shares two genes in common between the variations, fliG in the opposite orientation upstream of luxRI and an adenylosuccinate lyase encoding gene downstream. In E. coli, FliG is the flagellar motor switch that controls the spin direction of flagella (Roman et al., 1993). The characterized role of QS and motility in roseobacters was addressed previously (Zan et al., 2012), but none of the organisms containing the D topology have been investigated with respect to QS. The direct connection between QS and flagellar machinery may be an interesting avenue for future investigation. The other gene in this orientation putatively encodes an adenylosuccinate lyase, which is important in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway and in controlling the levels of AMP and fumarate inside the cell (Tsai et al., 2007), suggesting purine biosynthesis may respond to QS.

The presence of orphan luxI genes appears common, especially in the Sulfitobacter, Ruegeria, and Phaeobacter genera (Table A1).The synteny of these luxI and their adjacent genes is conserved in the H, I, and J topologies. In organisms that have these three orientations, there is a luxI-like gene of the Iδ. The LuxI of these topologies share >52% sequence similarity. Shared among the H, I, and J topologies are different types of putative histidine kinase (HK) encoding genes upstream of the orphan luxI, suggesting the protein is part of a two-component phosphorelay (Dutta et al., 1999; Stock et al., 2000). These genes are in the same direction as the luxI in H and I and in the opposite in J (Figure 2). In Vibrio harveyi, the hybrid two-component HK LuxN has been shown to activate gene circuits that lead to coordinated behaviors, such as bioluminescence, in response to AHLs (Freeman and Bassler, 1999; Laub and Goulian, 2007). The HKs found these topologies share modest identity with the Vibrio harveyi LuxN (≤26%) suggesting similar regulatory systems may be present in roseobacters. While the similarity of gene sequence does not directly predict regulatory cascades or phenotypes, the development of model systems for each of these topologies will prove valuable for comparative studies across lineage members.

Future directions

The repertoire of chemical signals in roseobacters is anticipated to be large and result in complex chemical signaling pathways in lineage members, some of which may contribute to interspecies interactions and should be investigated further. For example, uncharacterized roseobacters have been shown to be epibionts of the abundant cyanobacterial lineage Trichodesmium. While AHL-based interactions between Trichodesmium and select epibionts have been shown to stimulate mechanisms for phosphorus acquisition in this host (Hmelo et al., 2012; Van Mooy et al., 2012), a definitive role for roseobacters in this symbiosis has not yet been demonstrated. Similarly, it has been hypothesized that QS plays a role in the switch from mutualistic to antagonistic behavior proposed for P. gallaeciensis in its interactions with the phytoplankter Emiliana huxleyi (Seyedsayamdost et al., 2011). Finally, the relationships roseobacters have with vascular plants as they colonize plant material and transform plant-derived compounds (Buchan et al., 2000; Dang and Lovell, 2000; Buchan et al., 2001) is suggestive of inter-kingdom communication, such as that found in other α-proteobacteria [e.g., Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Sinorhizobium meliloti (Hughes and Sperandio, 2008)]. Research in these areas would help elucidate the role of QS in the ability of roseobacters to colonize and interact with a diverse group of organisms.

The presence of orphan luxR-like genes in Proteobacterial genomes has been widely described, and their gene products have been shown to respond to AHLs and other molecules produced by other QS systems in the same organism or by other organisms (Malott et al., 2009; Patankar and González, 2009; Sabag-Daigle et al., 2012). Furthermore, it is possible that these LuxR family proteins bind structurally similar molecules that are not related to QS. In fact, it has been shown that cross-domain signaling can be mediated through LuxR homologs that bind non-AHL eukaryotic molecules (Subramoni and Venturi, 2009). In contrast, detailed studies of orphan luxI-like gene products are rare and are an area ripe for study. Perhaps either novel non-LuxR-like proteins or proteins encoded by genes located in distal regions of the genome (Table A2) respond to the orphan LuxI-derived AHLs. Undoubtedly, more detailed characterization of such systems will lead to a better understanding of their biological roles in roseobacters as well as other lineages.

To date, experimental studies of QS in relatively few select roseobacters have revealed complex and multi-layered control mechanisms as well as novel signaling molecules. In addition to expanding our knowledge of these characterized systems, it is our hope that future studies also broaden our understanding of currently under investigated systems within the clade and their contribution to complex multi-species interactions.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees of LuxI-like and genetically linked LuxR-like sequences from 38 published roseobacter genomes were constructed. Protein alignments of the LuxI and LuxR homologs were done using the MUSCLE algorithm with default parameters (Edgar, 2004), and manually curated. The phylogenetic trees were generated using MEGA 5.2 following published methods (Hall, 2013). The Maximum Likelihood statistical method was used with the WAG model of amino acid substitution and gamma distribution with invariant sites (G+I) selected. Gaps were handled with a 95% partial deletion data treatment, and the phylogeny was tested with 1000 bootstrap replications (Tamura et al., 2011). Bootstrap values are reported in percentages and shown at nodes where values are >50%. Groups were divided and defined by natural divisions in the trees and gene topology in the genome (Figure 2). The LuxRI protein sequences of Vibrio fischeri (Accession: AAQ90231.1 and AAP22376.1) were used to root the trees. LuxR and LuxI homologs of six proteobacterial species with sequence similarity to at least one roseobacter sequence in each subgroup (>30% identity) were included in the alignments to assess the validity of the groupings. The non-roseobacter LuxRI included were: Sinorhizobium meliloti (Accession: ABC88593.1 and CAC46417.1), Bradyrhizobium elkanii (Accession: WP_018273827.1 and WP_018272735), Rhizobium leguminosarum (Accession: YP_002281222.1 and CAD20929.1), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Accession: WP_003501811.1 and AAZ50597.1), Pseudomonas putida (Accession: CAO85746.1 and CAO85747), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CAO85753.1 and CAO85754.1.

Table A1.

Paired LuxRI and orphan LuxIa homologs identified in the 38 sequenced roseobacters.

| Strains | Gene orientation | luxR gene locus | luxI gene locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2083 | A | RB2083_3272 | RB2083_3255 |

| Ruegeria sp. KLH11 | A | RKLH11_1559 | RKLH11_2275 |

| Roseovarius sp. 217 | A | ROS217_18272 | ROS217_18267 |

| Roseovarius sp. TM1035 | A | RTM1035_10475 | RTM1035_10485 |

| Ruegeria lacuscaerulensis ITI-1157 | A | SL1157_2477 | SL1157_2476 |

| Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 | A | SPO2286 | SPO2287 |

| Ruegeria sp. TW15 | A | RTW15_010100013877 | RTW15_010100013872 |

| Citreicella sp. 357 | B | C357_10197 | C357_10192 |

| Citreicella SE45 | B | CSE45_4055 | CSE45_4054 |

| Roseobacter denitrificans OCh 114 | B | RD1_1638 | RD1_1639 |

| Sagittula stellata E-37 | B | SSE37_11169 | SSE37_11164 |

| Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 | B | SPO0371 | SPO0372 |

| Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL 12 | B1 | DSHI_2852 | DSHI_2851 |

| Loktanella sp. SE62 | B1 | LSE62_0618 | LSE62_0617 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis 2.10 | B1 | PGA2_c03430 | PGA2_c03440 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis DSM 17395 | B1 | PGA1_c03880 | PGA1_c03890 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis ANG1 | B1 | ANG1_1316 | ANG1_1315 |

| Phaeobacter sp. Y4I | B1 | RBY4I_1689 | RBY4I_3631 |

| Ruegeria sp. KLH11 | B1 | RKLH11_1933 | RKLH11_260 |

| Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2150 | B1 | RB2150_14426 | RB2150_14421 |

| Roseobacter sp. AzwK-3b | B1 | RAZWK3B_04270 | RAZWK3B_04275 |

| Roseobacter sp. GAI101 | B1 | RGAI101_376 | RGAI101_3395 |

| Roseobacter sp. MED193 | B1 | MED193_10428 | MED193_10423 |

| Ruegeria lacuscaerulensis ITI-1157 | B1 | SL1157_0613 | SL1157_0612 |

| Ruegeria sp. R11 | B1 | RR11_2850 | RR11_2520 |

| Ruegeria sp. TW15 | B1 | RTW15_010100017779 | RTW15_010100017784 |

| Roseobacter sp. R2A57 | B2 | R2A57_2403 | R2A57_2404 |

| Thalassiobium R2A620 | B2 | TR2A62_3165 | TR2A62_3166 |

| TR2A62_3167 | |||

| Maritimibacter alkaliphilus HTCC2654 | B3 | RB2654_09024 | RB2654_09014 |

| Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2083 | B4 | RB2083_3265 | RB2083_730 |

| Roseobacter litoralis Och 149 | B4 | RLO149_c030690 | RLO149_c030680 |

| Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL 12 | C | DSHI_0311 | DSHI_0312 |

| Jannaschia sp. CCS1 | C | JANN_0619 | JANN_0620 |

| D | SKA53_05835 | SKA53_05830 | |

| Loktanella vestfoldensis SKA53 | SKA53_05840 | ||

| Loktanella sp. SE62 | D1 | LSE62_3230 | LSE62_3231 |

| LSE62_3229 | |||

| Oceanicola granulosus HTCC2516 | D1 | OG2516_02284 | OG2516_02294 |

| OG2516_02289 | |||

| Octadecabacter antarcticus 307 | D1 | OA307_2044 | OA307_4586 |

| OA307_3216 | |||

| Roseobacter sp. CCS2 | D1 | RCCS2_02083 | RCCS2_02078 |

| RCCS2_02088 | |||

| Octadecabacter arcticus 238 | D2 | OA238_4151 | OA238_2886 |

| OA238_3367 | |||

| Roseobacter sp. SK209-2-6 | E | RSK20926_22079 | RSK20926_22084 |

| Sulfitobacter NAS-14.1 | E | NAS141_01141 | NAS141_01136 |

| Maritimibacter alkaliphilus HTCC2654 | F | RB2654_20053 | RB2654_20048 |

| Roseovarius sp. 217 | G | ROS217_01405 | ROS217_01410 |

| Roseobacter litoralis Och 149 | G1 | RLO149_c036220 | RLO149_c036210 |

| Sulfitobacter NAS-14.1 | H | NAS141_00695 | |

| Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 | H | EE36_01635 | |

| Roseovarius nubinhibens ISM | I | ISM_03755 | |

| Oceanibulbus indolifex HEL45 | I | OIHEL45_00955 | |

| Ruegeria sp. R11 | J | RR11_2017 | |

| Roseobacter sp. MED193 | J | MED193_08053 | |

| Ruegeria sp. TW15 | J | RTW15_010100005486 | |

| Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL 12 | K | DSHI_4152 | |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis 2.10 | L | PGA2_c18970 | PGA2_c18960 |

| Phaeobacter sp. Y4I | L1 | RBY4I_1027 | RBY4I_3464 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis 2.10 | M | PGA2_c07460 | |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis DSM 17395 | M | PGA1_c07680 | |

| Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2150 | N | RB2150_11281 | RB2150_11291 |

| Roseobacter litoralis Och 149 | O | RLO149_c036590 | |

| Roseobacter sp. AzwK-3b | P | RAZWK3B_19371 | |

| Roseobacter sp. SK209-2-6 | Q | RSK20926_15126 | RSK20926_15131 |

| Roseobacter sp. GAI101 | Q1 | RGAI101_1101 | |

| Ruegeria lacuscaerulensis ITI-1157 | R | SL1157_1706 | |

| Ruegeria sp. TrichCH4B | S | SCH4B_1938 |

Homologs of LuxI encoding genes were determined using BlastP to characterized proteinsb (E-value < e-3) on Roseobase (www.roseobase.org) and are consistent with the genome annotations. The LuxR gene loci listed do not represent all homologs within the genomes, but were determined based using BlastP with the autoinducer binding domain sequence from Pfam (PF03472) on Roseobase, and proximity to luxI homologs. These were also consistent with genome annotations. Gene orientations are represented in Figure 2.

Orphan luxI homologs are defined as those that do not have an immediately adjacent luxR gene. All reported orphan luxI genes are located and at least 100 kb from the end of the draft genome contig.

bVibrio fischeri LuxI (AAP22376), Agrobacterium tumefaciens TraR (AAZ50597) and Phaeobacter gallaeciensis PgaI (YP_006571842).

Table A2.

Putative orphan LuxR encoding genes that do not have an adjacent luxI on the chromosome.

| Strains | luxR gene locus |

|---|---|

| Citreicella sp. 357 | C357_03001 |

| Citreicella sp. SE45 | CSE45_1818 |

| CSE45_4969 | |

| Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL 12 | Dshi_1550 |

| Dshi_1815 | |

| Dshi_1819 | |

| Jannaschia sp. CCS1 | Jann_1153 |

| Jann_2301 | |

| Jann_3193 | |

| Loktanella sp. SE62 | LSE62_3779 |

| Maritimibacter alkaliphilus HTCC2654 | RB2654_10983 |

| RB2654_03619 | |

| Oceanibulbus indolifex HEL-45 | OIHEL45_01695 |

| OIHEL45_02625 | |

| OIHEL45_13145 | |

| Oceanicola batsensis HTCC2597 | OB2597_03302 |

| Oceanicola granulosus HTCC2516 | OG2516_08027 |

| Oceanicola sp. S124 | OS124_010100017942 |

| OS124_010100007975 | |

| Octadecabacter antarcticus 238 | OA238_3367 |

| OA238_3623 | |

| Octadecabacter antarcticus 307 | OA307_2044 |

| Pelagibaca bermudensis HTCC2601 | R2601_24964 |

| R2601_10664 | |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis 2.10 | PGA2_c15480 |

| PGA2_c18970 | |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis DSM 17395 | PGA1_c15590 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis ANG1 | ANG1_869 |

| Phaeobacter sp. Y4I | RBY4I_896 |

| Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2083 | RB2083_1776 |

| Rhodobacterales bacterium HTCC2150 | RB2150_02239 |

| Roseobacter denitrificans OCh 114 | RD1_3967 |

| Roseobacter litoralis Och 149 | RLO149_c004710 |

| RLO149_c036470 | |

| Roseobacter sp. AzwK-3b | RAZWK3B_15865 |

| Roseobacter sp. CCS2 | RCCS2_00422 |

| Roseobacter sp. GAI101 | RGAI101_670 |

| Roseobacter sp. MED193 | MED193_03932 |

| Roseobacter sp. R2A57 | R2A57_3570 |

| Roseobacter sp. SK209-2-6 | RSK20926_03972 |

| RSK20926_18892 | |

| Roseovarius nubinhibens ISM | ISM_09921 |

| ISM_15650 | |

| Roseovarius sp. TM1035 | RTM1035_08219 |

| Roseovarius sp. 217 | ROS217_20327 |

| Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 | SPO1974 |

| Ruegeria sp. KLH11 | RKLH11_1390 |

| Ruegeria sp. R11 | RR11_2316 |

| Ruegeria sp. TM1040 | TM1040_3102 |

| TM1040_1212 | |

| Ruegeria sp. TW15 | RTW15_010100007191 |

| Ruegeria sp. TrichCH4B | SCH4B_0463 |

| SCH4B_4179 | |

| SCH4B_4368 | |

| SCH4B_4682 | |

| Ruegeria lacuscaerulensis ITI-1157 | SL1157_2844 |

| Sagittula stellata E-37 | SSE37_06082 |

| Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 | EE36_03628 |

| Sulfitobacter sp. NAS-14.1 | NAS141_08556 |

| Thalassiobium sp. R2A62 | TR2A62_0664 |

Homologs of LuxR encoding genes were determined using BlastP with the autoinducer binding domain sequence from Pfam (PF03472) on Roseobase www.roseobase.org).

References

- Barnard A. M. L., Bowden S. D., Burr T., Coulthurst S. J., Monson R. E., Salmond G. P. C. (2007). Quorum sensing, virulence and secondary metabolite production in plant soft-rotting bacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 362, 1165–1183 10.1098/rstb.2007.2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M., Neumann A., Schulz S., Simon M., Brinkhoff T. (2011). Tropodithietic acid production in Phaeobacter gallaeciensis is regulated by N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6576–6585 10.1128/JB.05818-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn J. B., Gram L., Belas R. (2007). Production of antibacterial compounds and biofilm formation by Roseobacter species are influenced by culture conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 442–450 10.1128/AEM.02238-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn J. B., Haagensen J. A., Bagge-Ravn D., Gram L. (2006). Culture conditions of Roseobacter strain 27-4 affect its attachment and biofilm formation as quantified by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3011–3015 10.1128/AEM.72.4.3011-3015.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn J. B., Nielsen K. F., Hjelm M., Hansen M., Bresciani J., Schulz S., Gram L. (2005). Ecology, inhibitory activity, and morphogenesis of a marine antagonistic bacterium belonging to the Roseobacter clade. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7263–7270 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7263-7270.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan A., Collier L. S., Neidle E. L., Moran M. A. (2000). Key aromatic-ring-cleaving enzyme, protocatechuate 3, 4-dioxygenase, in the ecologically important marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 4662–4672 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4662-4672.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan A., Gonzalez J. M., Moran M. A. (2005). Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 5665–5677 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5665-5677.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan A., Neidle E. L., Moran M. A. (2001). Diversity of the ring-cleaving dioxygenase gene pcaH in a salt marsh bacterial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 5801–5809 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5801-5809.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case R. J., Labbate M., Kjelleberg S. (2008). AHL-driven quorum-sensing circuits: their frequency and function among the Proteobacteria. ISME J. 2, 345–349 10.1038/ismej.2008.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case R. J., Longford S. R., Campbell A. H., Low A., Tujula N., Steinberg P. D., et al. (2011). Temperature induced bacterial virulence and bleaching disease in a chemically defended marine macroalga. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 529–537 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin-a-Woeng T. F. C., Bloemberg G. V., Lugtenberg B. J. J. (2003). Phenazines and their role in biocontrol by Pseudomonas bacteria. New Phytol. 157, 503–523 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00686.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill M. E. A., Chen L. L. (2011). Structural basis of acyl-homoserine lactone-dependent signaling. Chem. Rev. 111, 68–85 10.1021/cr1000817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli E. M., Williamson H., Tait K., Fuqua C. (2008). Acylated homoserine lactone signaling in marine bacterial systems, in Chemical Communication Among Bacteria. eds Winans S. C., Bassler B. L. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ), 251–272 [Google Scholar]

- Cude W. N., Mooney J., Tavanaei A. A., Hadden M. K., Frank A. M., Gulvik C. A., et al. (2012). Production of the antimicrobial secondary metabolite indigoidine contributes to competitive surface colonization by the marine roseobacter Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4771–4780 10.1128/AEM.00297-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang H. Y., Li T. G., Chen M. N., Huang G. Q. (2008). Cross-ocean distribution of Rhodobacterales bacteria as primary surface colonizers in temperate coastal marine waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 52–60 10.1128/AEM.01400-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang H. Y., Lovell C. R. (2000). Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 467–475 10.1128/AEM.66.2.467-475.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang H. Y., Lovell C. R. (2002). Seasonal dynamics of particle-associated and free-living marine Proteobacteria in a salt marsh tidal creek as determined using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Environ. Microbiol. 4, 287–295 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T., Miyamoto C. M., Wood T. K., Meighen E. A., Sorgeloos P., Verstraete W., et al. (2007). The natural furanone (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone disrupts quorum sensing-regulated gene expression in Vibrio harveyi by decreasing the DNA-binding activity of the transcriptional regulator protein LuxR. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 2486–2495 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov S., Dahmns H.-U., Yili H., Wahl M., Qian P.-Y. (2007). The effect of quorum-sensing blockers on the formation of marine microbial communities and larval attachment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60, 177–188 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R., Qin L., Inouye M. (1999). Histidine kinases: diversity of domain organization. Mol. Microbiol. 34, 633–640 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N., Case R. J., Longford S. R., Seyedsayamdost M. R., Steinberg P. D., Kjelleberg S., et al. (2011). Genomes and virulence factors of novel bacterial pathogens causing bleaching disease in the marine red alga Delisea pulchra. PLoS ONE 6:e27387 10.1371/journal.pone.0027387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folcher M., Gaillard H., Nguyen L. T., Nguyen K. T., Lacroix P., Bamas-Jacques N., et al. (2001). Pleiotropic functions of a Streptomyces pristinaespiralis autoregulator receptor in development, antibiotic biosynthesis, and expression of a superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 44297–44306 10.1074/jbc.M101109200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J. A., Bassler B. L. (1999). Sequence and function of LuxU: a two-component phosphorelay protein that regulates quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 181, 899–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C., Parsek M. R., Greenberg E. P. (2001). Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35, 439–468 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C., Winans S. C., Greenberg E. P. (1996). Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50, 727–751 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua W. C., Winans S. C. (1994). A LuxR-LuxI type regulatory system activates Agrobacterium Ti plasmid conjugal transfer in the presence of a plant tumor metabolite. J. Bacteriol. 176, 2796–2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelencsér Z., Choudhary K. S., Coutinho B. G., Hudaiberdiev S., Galbáts B., Venturi V., et al. (2012). Classifying the topology of AHL-driven quorum sensing circuits in Proteobacterial genomes. Sensors 12, 5432–5444 10.3390/s120505432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng H., Belas R. (2010). Expression of tropodithietic acid biosynthesis is controlled by a novel autoinducer. J. Bacteriol. 192, 4377–4387 10.1128/JB.00410-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J. M., Moran M. A. (1997). Numerical dominance of a group of marine bacteria in the alpha-subclass of the class Proteobacteria in coastal seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4237–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L., Grossart H. P., Schlingloff A., Kiorboe T. (2002). Possible quorum sensing in marine snow bacteria: production of acylated homoserine lactones by Roseobacter strains isolated from marine snow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 4111–4116 10.1128/AEM.68.8.4111-4116.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulvik C. A., Buchan A. (2013). Simultaneous catabolism of plant-derived aromatic compounds results in enhanced growth for members of the Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3716–3723 10.1128/AEM.00405-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentzer M., Riedel K., Rasmussen T. B., Heydorn A., Andersen J. B., Parsek M. R., et al. (2002). Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria by a halogenated furanone compound. Microbiology 148, 87–102 Available online at: http://mic.sgmjournals.org/content/148/1/87.long [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hmelo L. R., Van Mooy B. A. S., Mincer T. J. (2012). Characterization of bacterial epibionts on the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 67, 488–496 10.3354/ame01571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. T., Sperandio V. (2008). Inter-kingdom signalling: communication between bacteria and their hosts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 111–120 10.1038/nrmicro1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joernvall H., Persson B., Krook M., Atrian S., Gonzalez-Duarte R., Jeffery J., et al. (1995). Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR). Biochemistry 34, 6003–6013 10.1021/bi00018a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch B., Liljefors T., Persson T., Nielsen J., Kjelleberg S., Givskov M. (2005). The LuxR receptor: the sites of interaction with quorum-sensing signals and inhibitors. Microbiology 151, 3589–3602 10.1099/mic.0.27954-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub M. T., Goulian M. (2007). Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 121–145 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlam A. V., Moore B. A., Xu Z. (2004). The crystal structure of ribosomal chaperone trigger factor from Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13436–13441 10.1073/pnas.0405868101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malott R. J., O'grady E. P., Toller J., Inhülsen S., Eberl L., Sokol P. A. (2009). A Burkholderia cenocepacia orphan luxR homolog is involved in quorum-sensing regulation. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2447–2460 10.1128/JB.01746-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manefield M., De Nys R., Naresh K., Roger R., Givskov M., Peter S., et al. (1999). Evidence that halogenated furanones from Delisea pulchra inhibit acylated homoserine lactone (AHL)-mediated gene expression by displacing the AHL signal from its receptor protein. Microbiology 145, 283–291 10.1099/13500872-145-2-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens T., Gram L., Grossart H.-P., Kessler D., Muller R., Simon M., et al. (2007). Bacteria of the Roseobacter clade show potential for secondary metabolite production. Microb. Ecol. 54, 31–42 10.1007/s00248-006-9165-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed N. M., Cicirelli E. M., Kan J., Chen F., Fuqua C., Hill R. T. (2008). Diversity and quorum-sensing signal production of Proteobacteria associated with marine sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 75–86 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadell C. D., Xavier J. B., Foster K. R. (2009). The sociobiology of biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 206–224 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadell C. D., Xavier J. B., Levin S. A., Foster K. R. (2008). The evolution of quorum sensing in bacterial biofilms. PLoS Biol. 6:e14 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealson K. H., Platt T., Hastings J. W. (1970). Cellular control of the synthesis and activity of the bacterial luminescent system. J. Bacteriol. 104, 313–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. J., Griffin L. E., Bowles K. M., Meile C., Gifford S., Givens C. E., et al. (2010). Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J. 4, 784–798 10.1038/ismej.2009.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng W.-L., Bassler B. L. (2009). Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 197–222 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas K. M., Weingart C. L., Winans S. C. (2004). Chemical communication in proteobacteria: biochemical and structural studies of signal synthases and receptors required for intercellular signalling. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 755–769 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patankar A. V., González J. E. (2009). An orphan luxR homolog of Sinorhizobium meliloti affects stress adaptation and competition for nodulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 946–955 10.1128/AEM.01692-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzelt D., Wang H., Buchholz I., Rohde M., Grobe L., Pradella S., et al. (2013). You are what you talk: quorum sensing induces individual morphologies and cell division modes in Dinoroseobacter shibae. ISME J. . Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.107 10.1038/ismej.2013.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Porsby C. H., Nielsen K. F., Gram L. (2008). Phaeobacter and ruegeria species of the Roseobacter clade colonize separate niches in a danish turbot (Scophthalmus maximus)-rearing farm and antagonize Vibrio anguillarum under different growth conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 7356–7364 10.1128/AEM.01738-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D., Webb J. S., Holmstrom C., Case R., Low A., Steinberg P., et al. (2007). Low densities of epiphytic bacteria from the marine alga Ulva australis inhibit settlement of fouling organisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7844–7852 10.1128/AEM.01543-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D., Webb J. S., Kjelleberg S. (2006). Microbial colonization and competition on the marine alga Ulva australis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5547–5555 10.1128/AEM.00449-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman S. J., Frantz B. B., Matsumura P. (1993). Gene sequence, overproduction, purification and determination of the wild-type level of the Escherichia coli flagellar switch protein FliG. Gene 133, 103–108 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90232-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby E. G. (1996). Lessons from a cooperative, bacterial-animal association: the Vibrio fischeri–Euprymna scolopes light organ symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50, 591–624 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabag-Daigle A., Soares J. A., Smith J. N., Elmasry M. E., Ahmer B. M. M. (2012). The acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) receptor, SdiA, of E. coli and Salmonella does not respond to indole, but at high concentrations indole can interfere with AHL detection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5424–5431 10.1128/AEM.00046-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A. L., Greenberg E. P., Oliver C. M., Oda Y., Huang J. J., Bittan-Banin G., et al. (2008). A new class of homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals. Nature 454, U595–U596 10.1038/nature07088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A. L., Val D. L., Hanzelka B. L., Cronan J. E., Greenberg E. P. (1996). Generation of cell-to-cell signals in quorum sensing: acyl homoserine lactone synthase activity of a purified Vibrio fischeri LuxI protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9505–9509 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimel J. P., Weintraub M. N. (2003). The implications of exoenzyme activity on microbial carbon and nitrogen limitation in soil: a theoretical model. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 549–563 10.1016/S0038-0717(03)00015-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedsayamdost M. R., Case R. J., Kolter R., Clardy J. (2011). The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat. Chem. 3, 331–335 10.1038/nchem.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider J., Thibault G., Houry W. A. (2008). The AAA+ superfamily of functionally diverse proteins. Genome Biol. 9, 216 10.1186/gb-2008-9-4-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. (2000). Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 183–215 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramoni S., Venturi V. (2009). LuxR-family ‘solos’: bachelor sensors/regulators of signalling molecules. Microbiology 155, 1377–1385 10.1099/mic.0.026849-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. W., Schupp P. J., Baillie H. J., Charlton T. S., De Nys R., Kjelleberg S., et al. (2004). Evidence for acyl homoserine lactone signal production in bacteria associated with marine sponges. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 4387–4389 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4387-4389.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel V., Kunze B., Verma P., Wagner-Dobler I., Schulz S. (2009). New structural variants of homoserine lactones in bacteria. Chembiochem 10, 1861–1868 10.1002/cbic.200900126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thole S., Kalhoefer D., Voget S., Berger M., Engelhardt T., Liesegang H., et al. (2012). Phaeobacter gallaeciensis genomes from globally opposite locations reveal high similarity of adaptation to surface life. ISME J. 6, 2229–2244 10.1038/ismej.2012.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M., Koo J., Yip P., Colman R. F., Segall M. L., Howell P. L. (2007). Substrate and product complexes of Escherichia coli adenylosuccinate lyase provide new insights into the enzymatic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 541–554 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mooy B. A. S., Hmelo L. R., Sofen L. E., Campagna S. R., May A. L., Dyhrman S. T., et al. (2012). Quorum sensing control of phosphorus acquisition in Trichodesmium consortia. ISME J. 6, 422–429 10.1038/ismej.2011.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter Y. A., Deming J. W., Jumars P. A., Krieger-Brockett B. B. (1998). A predictive model of bacterial foraging by means of freely released extracellular enzymes. Microb. Ecol. 36, 75–92 10.1007/s002489900095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Dobler I., Bibel H. (2006). Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 255–280 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Dobler I., Thiel V., Eberl L., Allgaier M., Bodor A., Meyer S., et al. (2005). Discovery of complex mixtures of novel long-chain quorum sensing signals in free-living and host-associated marine alphaproteobacteria. Chembiochem 6, 2195–2206 10.1002/cbic.200500189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace K. K., Bao Z.-Y., Dai H., Digate R., Schuler G., Speedie M. K., et al. (1995). Purification of crotonyl-CoA reductase from Streptomyces collinus and cloning, sequencing and expression of the corresponding gene in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 233, 954–962 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.954_3.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters C. M., Bassler B. L. (2005). Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 319–346 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zan J., Fricke W. F., Fuqua C., Ravel J., Hill R. T. (2011). Genome sequence of Ruegeria sp. strain KLH11, an N-acylhomoserine lactone-producing bacterium isolated from the marine sponge Mycale laxissima. J. Bacteriol. 193, 5011–5012 10.1128/JB.05556-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zan J., Heindl J. E., Liu Y., Fuqua C., Hill R. T. (2013). The CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay system is regulated by quorum sensing and controls flagellar motility in the marine sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11. PLoS ONE 8:e66346 10.1371/journal.pone.0066346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zan J. D., Cicirelli E. M., Mohamed N. M., Sibhatu H., Kroll S., Choi O., et al. (2012). A complex LuxR-LuxI type quorum sensing network in a roseobacterial marine sponge symbiont activates flagellar motility and inhibits biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 916–933 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08149.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z. P., Caspi R., Helinski D., Knauf V., Sykes S., O'byrne C., et al. (2003). Nucleotide sequence based characterizations of two cryptic plasmids from the marine bacterium Ruegeria isolate PR1b. Plasmid 49, 233–252 10.1016/S0147-619X(03)00014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Hall B. G. (2013). Building phylogenetic trees from molecular data with MEGA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1229–1235 10.1093/molbev/mst012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. J., Griffin L. E., Bowles K. M., Meile C., Gifford S., Givens C. E., et al. (2010). Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J. 4, 784–798 10.1038/ismej.2009.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecularx evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]