Abstract

Background

There is little information about the use of text messaging (texting) devices among resident and faculty physicians for patient-related care (PRC).

Objective

To determine the prevalence, frequency, purpose, and concerns regarding texting among resident and attending surgeons and to identify factors associated with PRC texting.

Design

Email survey

Setting

University medical center and its affiliated hospitals

Participants

Surgery resident and attending staff

Outcome Measures

Prevalence, frequency, purpose, and concerns regarding patient-related care text messaging.

Results

Overall, 73 (65%) surveyed physicians responded, including 45 resident (66%) and 28 attending surgeons (62%). All respondents owned a texting device. Majority of surgery residents (88%) and attendings (71%) texted residents while only 59% of residents and 65% of attendings texted other faculty. Most resident to resident text occurred at a frequency of 3–5 times/day (43%) compared to most attending to resident texts which occurred 1–2 times/day (33%). Most resident to attending (25%) and attending to attending (30%) texts occurred 1–2 times/day. Among those that texted, PRC was the most frequently reported purpose for resident to resident (46%), resident to attending (64%), attending to resident (82%), and attending to other attending staff (60%) texting. Texting was the most preferred method to communicate about routine PRC (47% of residents vs. 44% of attendings). Age (odds ratio: 0.86, 95% confidence interval: 0.79–0.95; p=0.003), but not sex, specialty/clinical rotation, academic rank or PGY level predicted PRC texting.

Conclusions

The majority of resident and attending staff surveyed utilize texting, mostly for PRC. Texting was preferred for communicating routine PRC information. Our data may facilitate the development of guidelines for the appropriate use of PRC texting.

Keywords: Text messaging, patient care, communication, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

Mobile telephone text messaging (texting) is a relatively new, yet commonplace phenomenon. The first text message was sent in 1992 (1), but now mobile telephones with texting capabilities are commonplace. It is estimated that 83% of United States adults now own texting devices (2). The first use of patient related care (PRC) texting was reported in 2002 when clinicians texted to remind patients with asthma to use their inhalers (3). Subsequently, texting has been utilized for a variety of clinical, administrative and research applications (4–13).

Communication between and among physicians of different specialties and training levels is essential to provide optimal patient care (14). The 2011 Joint Commission sentinel event report identified poor communication as the number one root cause of delays in patient treatment and the second leading cause of operative/post-operative complications (15). Telephone communication has been facilitated for decades by beeper paging systems, but these are associated with delays in response times (16) and interruptions that may distract physicians’ attention and compromise patient care (17–19). Use of texting devices may ameliorate these problems. Unlike a beeper paging system that requires a telephone response to obtain the message conveyed, a text allows the recipient to obtain the message instantly and respond, if necessary, immediately or in delayed fashion as appropriate. Furthermore, a text may be referenced at a later time to review information that may have otherwise been forgotten. PRC texting may have potential disadvantages as well. Texts may not be suitable for conveying urgent or emergent messages, as the recipient may not be available and the sender may not be able to determine if the message was received. Finally, use of patient identifiers while texting may compromise patient confidentiality and be non-compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations (20, 21).

Despite their ubiquity, little is known about the use of texting devices among physicians. This study aimed to determine the prevalence, frequency, purpose, and concerns regarding texting among resident and attending surgeons and to identify factors associated with PRC texting.

METHODS

At the beginning of the 2011–2012 academic year, we conducted a focus group of physicians at UC Davis Medical Center and developed a preliminary survey. The modified final email survey included 5 domains: Demographic Information (age, sex, academic rank or postgraduate year [PGY] level, clinical service or specialty, hospital setting), Purpose of Texting (personal communication, logistics, PRC), Prevalence and Frequency of Texting (how many physicians text and how often), Preferences for Texting (for routine, urgent, or emergent PRC), and Texting Comfort and Concerns.

After approval by our institutional review board, a total of 113 physicians within the department of surgery, including residents (N=68) and attending staff (N=45) were sent an email letter asking them to complete our survey (Survey Monkey, Palo Alto, CA). All respondents were residents or attending surgery staff at our university medical center and/or its affiliated institutions (a pediatric hospital, a large health maintenance organization, a community hospital, and military and veterans affair hospitals). The email included a cover letter from the principal investigators, a brief summary of the study, and a link to the survey. Response was voluntary and implied informed consent. The survey did not require respondents to identify themselves. Respondents were asked to answer all questions, but were allowed to skip questions for any reason. At two week intervals, non-respondents were reminded about the survey with up to two follow-up email solicitations along with a link to the email survey. After this, no additional attempts to contact non-respondents were made. With minor exceptions, the survey administered to surgery residents was identical to that given to attending staff. For example, residents were asked their PGY level, while attending staff were asked their academic rank.

The prevalence, frequency, purpose, and concerns about texting assessed over the survey’s five domains were examined by gender, age, academic rank or PGY level, and specialty or current clinical rotation. Unless specifically stated, all resident staff responses were to refer to their current clinical rotation. Results were reported for surgery resident and attending staff together (all respondents), as well as resident-only and attending staff-only groups. Descriptive statistics were used for all survey responses and physician characteristics. Proportions were compared between surgery resident and attending staff groups using a two sample test of proportions. Because respondents chose not to answer some questions, the frequencies reported reflect the total number of respondents for a particular question. We used univariate logistic regression models to predict the likelihood of a respondent reporting PRC texting based upon their age, sex, specialty or clinical rotation, and academic rank or PGY level. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Demographic Information

The overall survey response rate was 65% (N=73). The response rate for residents was 66% (N=45) and 62% (N=28) for attending staff surgeons. Table 1 summarizes the demographic factors of survey respondents. Briefly, respondents were most commonly males working at UC Davis Medical Center on the Gastrointestinal Surgery, Burns/Plastic Surgery, or Trauma and Emergency Surgery services. All respondents reported owning a texting device. Only 12% of respondents reported not using a texting device while at work. The proportion of residents and attending staff not utilizing any source of texting at work did not differ (9% vs. 17%, p=0.33).

TABLE 1.

Domain 1: Respondent Demographic Information*.

| All Respondents N=73 (%) | Surgery Residents N=48 (%) | Surgery Attendings N=25 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 32 | 46 | ||

| Sex | Male | 42 (70) | 22(61) | 20(83) |

| Female | 18 (30) | 14(39) | 4(17) | |

| PGY Level | I | NA | 6 (17) | NA |

| II | NA | 5 (14) | NA | |

| III | NA | 4 (11) | NA | |

| IV | NA | 5 (14) | NA | |

| V | NA | 5 (14) | NA | |

| VI or higher | NA | 11 (31) | NA | |

| Academic Rank | Assistant Professor | NA | NA | 10 (42) |

| Associate Professor | NA | NA | 6 (25) | |

| Professor | NA | NA | 8 (33) | |

| Hospital Setting | University | 60 | 41 (85) | 19 (79) |

| VA Hospital | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | |

| Military Hospital | 2 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | |

| Multiple | 4 | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | |

| Private | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| HMO | 2 | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Specialty/Clinic Rotation | General/GI Surgery | 15 | 12 (25) | 3 (12.5) |

| Trauma/Emergency | 17 | 11 (23) | 6 (25) | |

| Vascular | 9 | 4 (8) | 5 (20) | |

| Surgical Oncology | 5 | 3 (6) | 2 (8) | |

| CT Surgery | 7 | 4 (8) | 3 (13) | |

| Transplant | 5 | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Pediatric | 1 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other(Burns/Plastic) | 13 | 8 (17) | 5 (20) | |

| Device Used | Cellular Phone | 35 (52) | 19 (44) | 16 (67) |

| Text Pager | 4 (6) | 3 (7) | 1 (4) | |

| Both | 20 (30) | 17 (40) | 3 (13) | |

| None | 8 (12) | 4 (9) | 4 (17) |

Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of respondents for a given question.

Purpose of Texting

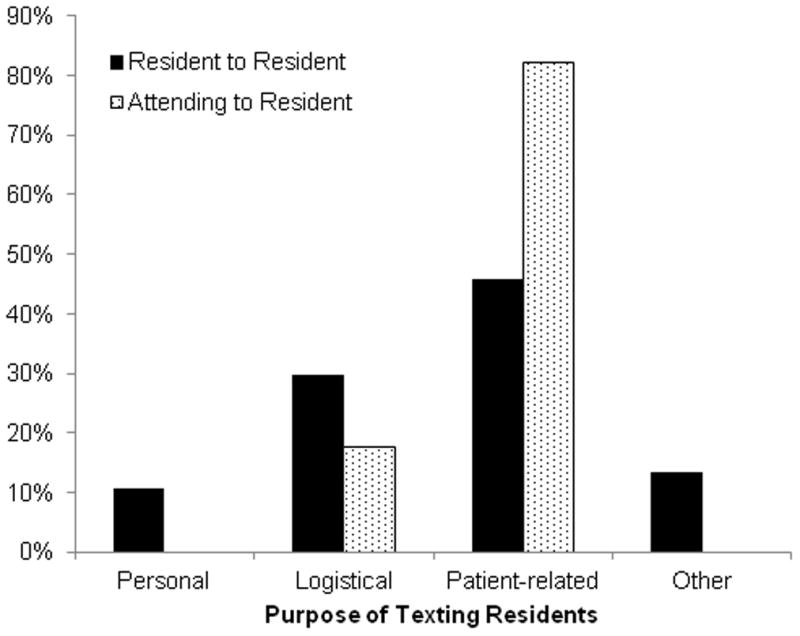

We asked both residents and attending staff their reasons for texting residents. Among respondents, 12% (N=5) of resident staff and 29% (N=7) of attending staff reported not texting residents. Of attending surgeons whom texted, 82% texted residents about PRC (Figure 1a). PRC was also the most common (46%) reason for resident to resident texting (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Domain 2: Purpose of Text Messaging Residents. Not all respondents answered every question. Values represented are of those of Surgery Residents (N=37) and Surgery Attendings (N=17) who responded and texted. There were no statistically significant differences between the Surgery Residents and Surgery Attendings groups on two sample proportions test.

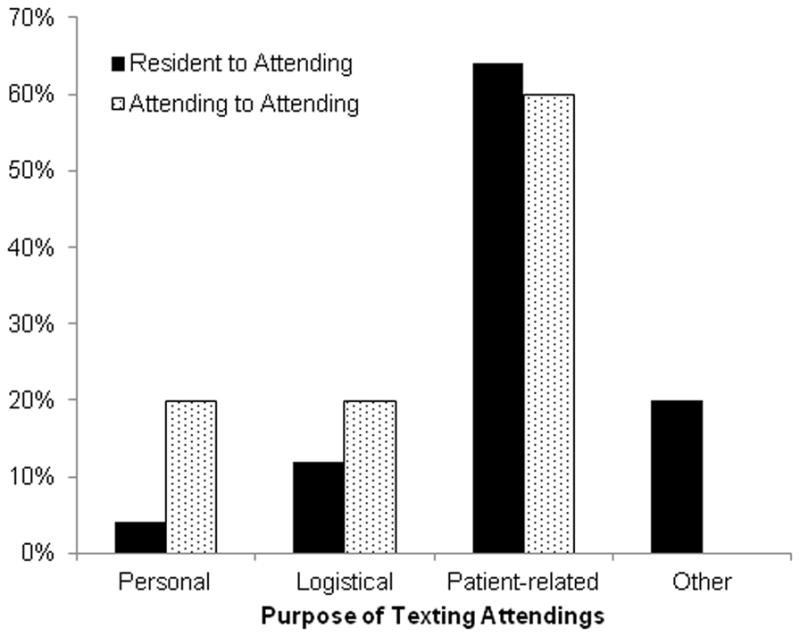

Figure 1b. Domain 2: Purpose of Text Messaging Attendings. Not all respondents answered every question. Values represented are of those of Surgery Residents (N=25) and Surgery Attendings (N=15) who responded and texted. There were no statistically significant differences between the Surgery Residents and Surgery Attendings groups on two sample proportions test.

We also asked both attendings and residents their reasons for texting attending staff. Attending staff (35%, N=8) were less likely than residents (41%, N=17) to report not texting other attendings. Among self-identified texters, the majority of attending to attending texts (60%) and resident to attending texts (64%) were about PRC (Figure 1b). Residents and attending staff did not differ significantly in their reported reasons for texting either residents or attending staff.

Prevalence and Frequency of Texting

We asked both residents and attending staff to identify the method of communication they used most frequently to communicate with residents or attending staff on their clinical service. As depicted in Table 2, both resident and attending staff most frequently used non-texting communication (person to person contact or a page followed by a phone call) with other resident or attending staff. Resident and attending surgery staff differed only with respect to their use of direct telephone communication. Compared to residents, attending staff were more likely to utilize direct telephone communication when contacting residents (0% vs. 12.5%, p=0.03) or other attendings (8% vs. 33%, p=0.01).

TABLE 2.

Domain 3: Prevalence of Texting*

| All Respondents (%) | Surgery Residents (%) | Surgery Attendings (%) | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method used most frequently to communicate with residents | In Person | 22 (36) | 15 (40) | 7 (29) | 0.38 |

| Direct Phone | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.5) | 0.03 | |

| Page then Phone | 28 (45) | 16 (42) | 12 (50) | 0.54 | |

| Text | 7 (11) | 5 (13) | 2 (8) | 0.54 | |

| Other | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.27 | |

| Method used most frequently to communicate with attendings | In Person | 14 (22) | 10 (26) | 4 (17) | 0.40 |

| Direct Phone | 11 (17.5) | 3 (8) | 8 (33) | 0.01 | |

| Page then Phone | 32 (51) | 22 (58) | 10 (42) | 0.21 | |

| Text | 4 (6.5) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 1.00 | |

| Other | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 0.83 | |

| Do you receive patient-related care texts from residents? | Yes | 51 (82) | 30 (79) | 21 (84) | 0.63 |

| No | 11 (18) | 8 (21) | 3 (16) | ||

| Do you receive patient-related care texts from attendings? | Yes | 28 (44) | 12 (31) | 16 (67) | 0.005 |

| No | 35 (56) | 27 (69) | 8 (33) |

Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of respondents for a given question. P-values represent comparisons between the Surgery Resident and Surgery Attending groups.

Overall, a similar proportion of both residents (79%) and attendings (84%) reported receiving texts from residents about PRC (79% vs. 84%, p=0.63). In contrast, attending staff reported receiving PRC texts from attending physicians more commonly than did residents (67% vs. 31%, p=0.005).

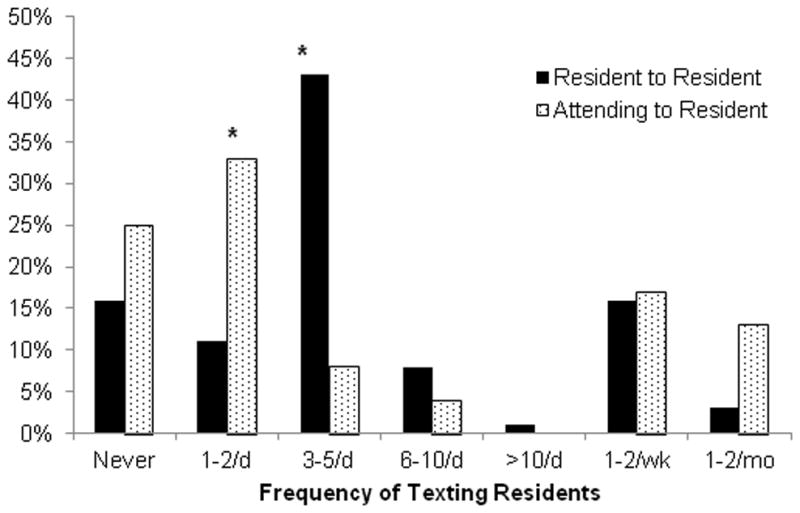

As depicted in Figure 2a, residents texted other residents more frequently than did attending staff. Residents were more likely to text other residents about PRC 3–5 times per day than were attending staff (43%, N=16 vs. 8%, N=2; p=0.003). Conversely, attending staff were more likely to text residents about PRC 1–2 times per day (33%, N=8 vs. 11%, N=4; p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Domain 3: Frequency of Texting Residents. Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of Surgery Residents (N=39) and Surgery Attendings (N=24) who responded. *Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) on two sample proportions test between the Surgery Resident and Surgery Attending groups.

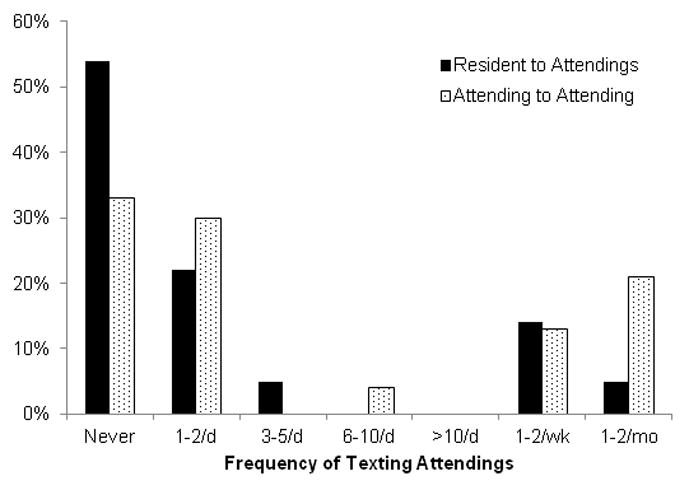

Figure 2b. Domain 3: Frequency of Texting Attending Staff. Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of Surgery Residents (N=37) and Surgery Attendings (N=24) who responded. There were no statistically significant differences between the Surgery Residents and Surgery Attendings groups on two sample proportions test.

Attending staff were more likely than residents to text other attending staff 1–2 times per month (21%, N=5 vs. 5%, N=2; p=0.05). Otherwise, attending and resident staff did not differ significantly with respect to the frequency with which they texted about PRC to attending surgeons.

Preferences for Texting

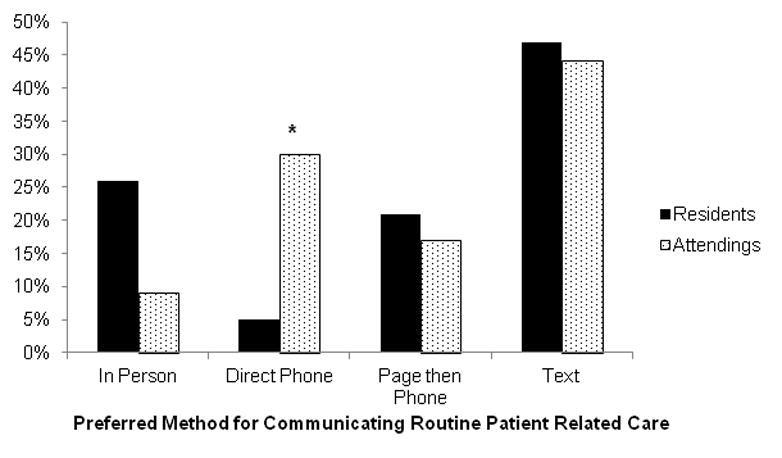

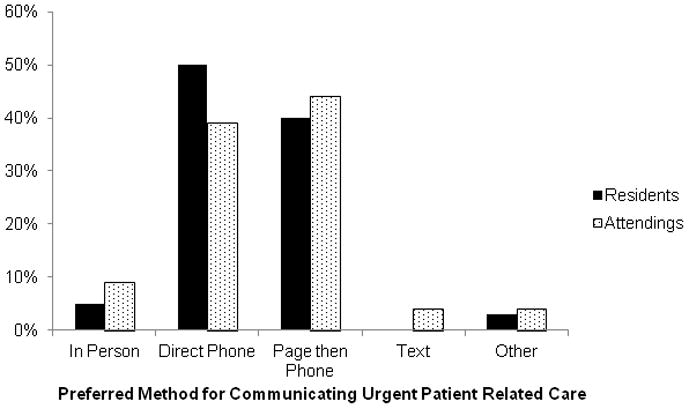

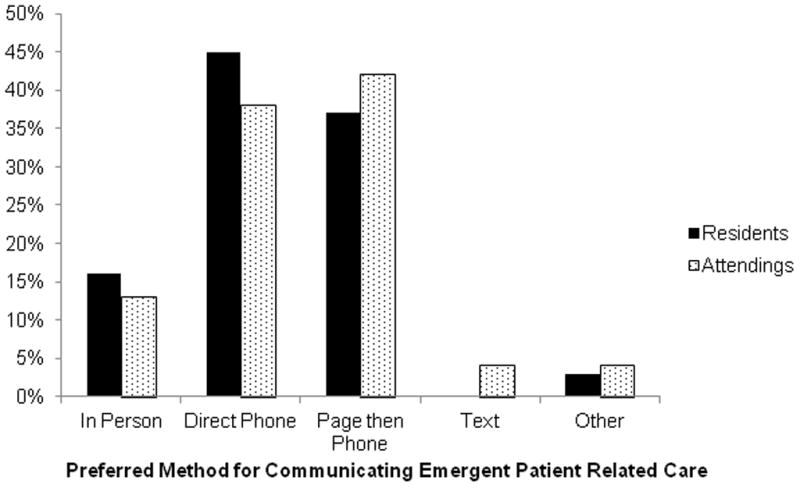

Respondents were asked about their preferences for receiving PRC information that was routine, urgent, or emergent (Figures 3a–3c). Among resident and attending staff, texting was the most preferred method of communicating routine PRC information (46%). In-person communication and beeper page followed by a telephone conversation were equally preferred for routine PRC issues (19.5%, respectively). For issues regarding routine PRC, resident and attending surgery staff differed only in that attending physicians preferred direct telephone communication (5% vs. 30%, p=0.007).

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Domain 4: Preferences for Texting. Preferred Method of Communicating Routine Patient Related Care. Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of Surgery Residents (N=38) and Surgery Attendings (N=23) who responded. *Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) on two sample proportions test between the Surgery Resident and Surgery Attending groups.

Figure 3b. Domain 4: Preferences for Texting. Preferred Method of Communicating Urgent Patient Related Care. Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of Surgery Residents (N=37) and Surgery Attendings (N=23) who responded. There were no statistically significant differences between the Surgery Residents and Surgery Attendings groups on two sample proportions test.

Figure 3c. Domain 4: Preferences for Texting. Preferred Method of Communicating Emergent Patient Related Care. Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of Surgery Residents (N=38) and Surgery Attendings (N=24) who responded. There were no statistically significant differences between the Surgery Residents and Surgery Attendings groups on two sample proportions test.

For communicating urgent and emergent PRC information, 46.5% and 42% of attending and residents, respectively, preferred direct telephone contact. Resident and attending staff did not differ significantly regarding their preferred means of communicating either urgent or emergent PRC information.

Texting Comfort and Concerns

We asked how comfortable resident and attending staff were with texting residents about PRC (Table 3). Resident and attending surgery staff did not differ with respect to their reported comfort texting residents about PRC with the majority of both residents (61%) and attending staff (68%) being either “comfortable” or “very comfortable” texting residents for this purpose.

TABLE 3.

Domain 5: Texting Comfort and Concerns*

| All Respondents (%) | Surgery Residents (%) | Surgery Attendings (%) | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How comfortable are you texting residents about patient-related care? | Very Uncomfortable | 5 (8.5) | 4 (11) | 1 (4) | 0.33 |

| Somewhat Uncomfortable | 8 (13.5) | 4 (11) | 4 (17) | 0.50 | |

| Neither Uncomfortable Nor Comfortable | 9 (15) | 6 (17) | 3 (13) | 0.67 | |

| Comfortable | 18 (30) | 9 (25) | 9 (38) | 0.28 | |

| Very Comfortable | 20 (33) | 13 (36) | 7 (30) | 0.63 | |

| How comfortable are you texting attendings about patient-related care? | Very Uncomfortable | 6 (10) | 4 (11) | 2 (8) | 0.70 |

| Somewhat Uncomfortable | 12 (20) | 10 (27) | 2 (8) | 0.07 | |

| Neither Uncomfortable Nor Comfortable | 14 (23) | 10 (27) | 4 (17) | 0.37 | |

| Comfortable | 15 (24) | 6 (16) | 9 (38) | 0.05 | |

| Very Comfortable | 14 (23) | 7 (19) | 7 (30) | 0.32 | |

| Texting is secure | Strongly Agree | 7 (11) | 7 (18) | 0 (0) | 0.03 |

| Mostly Agree | 11 (17) | 6 (15) | 5 (21) | 0.54 | |

| Neither Agree Nor Disagree | 21 (33) | 12 (30) | 9 (38) | 0.51 | |

| Mostly Disagree | 20 (31) | 11 (28) | 9 (38) | 0.41 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 5 (8) | 4 (10) | 1 (4) | 0.38 | |

| I am concerned my text message was not received | Strongly Agree | 17 (27) | 12 (31) | 5 (21) | 0.39 |

| Mostly Agree | 21 (33) | 13 (33) | 8 (33) | 1.00 | |

| Neither Agree Nor Disagree | 10 (16) | 7 (18) | 3 (13) | 0.61 | |

| Mostly Disagree | 13 (21) | 5 (13) | 8 (33) | 0.06 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.27 | |

| I respond to all texts to confirm receipt | Strongly Agree | 10 (15.5) | 6 (15) | 4 (17) | 0.83 |

| Mostly Agree | 24 (37) | 15 (39) | 9 (38) | 0.94 | |

| Neither Agree Nor Disagree | 12 (18.5) | 7 (18) | 5 (21) | 0.77 | |

| Mostly Disagree | 11 (17) | 6 (15) | 5 (21) | 0.54 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 8 (12) | 7 (18) | 1 (4) | 0.10 |

Not all respondents answered every question. Percentages were determined based upon the number of respondents for a given question. P-values represent comparisons between the Surgery Resident and Surgery Attending groups.

Answers were more evenly distributed when residents and attendings were asked about their comfort texting attending staff. However, compared to residents, a greater proportion of attending staff reported being “comfortable” or “very comfortable” texting other attending staff about PRC information (35% vs. 68%, p=0.01). Compared to attending staff, a greater proportion of resident staff stated that they were “somewhat uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable” texting attendings, but this was not significant (38% vs.16%, p=0.07).

When all respondents were asked about their concerns regarding texting, 28% “strongly” or “mostly” agreed that texting was secure while 39% “mostly” or “strongly” disagreed that texting was secure (Table 3). This difference was not significant (p=0.19). Residents were more likely than attending surgeons to “strongly” agree that texting is secure (0% vs. 18%, p=0.03). Respondents were asked about their level of concern regarding whether or not their text message was received. Those that “mostly” or “strongly” agreed that they would be concerned outnumbered those that would be similarly unconcerned (24% vs. 60%, p<0.001). Resident and attending surgeons did not differ significantly in their level of concern about text message receipt. When asked if they routinely respond to text messages to confirm receipt, respondents were most likely to “mostly” or “strongly” agree (52.5%). Residents and attending staff did not differ in their likelihood of confirming text message receipt.

Univariate Logistic Regression

Reported use of PRC texting was not predicted by respondent sex, specialty/clinical rotation, academic rank or PGY level. Increasing age was, however, associated with a decreased likelihood of texting (OR 0.86, CI 0.79–0.95; p=0.003).

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that the majority of surgery resident and attending staff participating in our general surgery residency program utilize texting, primarily for PRC. While beeper page and telephone conversation are the most common means of PRC communication, over 1/3 of our respondents also used texting for this purpose. In fact, texting was the most preferred method of communicating routine PRC information. Increasing age was associated with a decreased likelihood of texting, but respondent sex, specialty/clinical rotation, academic rank or PGY levels were not.

Our respondents’ demographics parallel the changing face of general surgery. While approximately 20% of attending staff were female, among residents this proportion was 40%. The role of sex on text message use is unclear; some studies indicated no difference between men and women (2), while others indicated that women use their texting devices more than men (22, 23). In our study, respondent sex did not predict texting behavior. Consistent with other studies, we found that older age was associated with a decreased likelihood of texting (2, 22, 24). Race/ethnicity, income, and education level have also been shown to predict use of texting (2, 22, 23), but we did not ask this information specifically of our respondents. Since everyone surveyed in our study was a physician, the educational background of our population was fairly homogeneous. Furthermore, we did not see the benefit of asking about income level, since our population was composed of two well-defined subgroups: residents (lower income earners) and attending staff (higher income earners). Within each of these two subgroups, income levels are fairly homogeneous and would be unlikely to be associated with differences in texting behavior.

PRC was the most commonly given reason for texting among our respondents. Hensel et al performed a web survey of 68 Family Practice physicians’ attitudes toward texting (25). About 34% of respondents used texting in their practice, which was lower than noted in our study. We reported that 82% of respondents texted residents and 61.5% texted attending staff. Hensel et al noted that, of respondents who texted, 65% used it to communicate with colleagues; use of PRC texting was not asked explicitly (25).

In a nationally representative telephone survey, Smith noted that 73% of American adults send and receive text messages (2). This is similar to what we found in our population of surgeons and surgical trainees with respect to PRC information. Overall, 72.5% of texting respondents texted residents and 54.5% texted attending staff about PRC at least once per day. Smith noted that text users send or receive an average of 41.5 texts daily (2). We did not assess the number of texts sent or received daily, however. Of interest, resident staff did not differ much in their prevalence or frequency of texting from attending surgeon faculty. One area where they did differ, however, was in their use of direct telephone communication; attending staff were more likely to report using telephone conversation to communicate with residents or other attending staff. Attending staff were also more likely to prefer direct telephone communication regarding routine PRC. These findings are consistent with the differences between “high control-motivated knowledge workers” and “low control-motivated knowledge workers” summarized by Spiegelman and Detsky (26), and may represent the power dynamic that exists between residents and attending surgeons. In this model, attending staff represent “high control-motivated knowledge workers” who initiate communication synchronously (such as by telephone) to increase efficiency. Resident staff represent “low control-motivated knowledge workers” who may choose to initiate communication asynchronously (such as by text message), which can lead to delays in response and overall inefficiency.

PRC texting has had limited evaluation among other medical specialties. Soto et al surveyed 4,018 anesthesiologists about personal cellular telephone use in the operating room and intensive care unit (ICU) (27). Although only 17% reported using cellular telephones, those who did noted fewer communication delays. Unlike our study, however, Soto et al focused on global cellular telephone use and not texting. O’Connor et al surveyed the impact of introducing texting devices to ICU physicians, nurses, and ancillary healthcare providers on communication, team relationships, staff satisfaction, and perceived benefit to patient care (28). Of 106 respondents, only 17% reported a negative influence on communication. Respondents overwhelmingly reported that use of these devices improved the speed and reliability of communication (92% for each), enabled better coordination of ICU team members (88%), and both improved morale (67%), and overall patient care (89%). Similar positive perceptions were obtained when Wu et al surveyed a group of internal medicine residents and ward nursing staff regarding potential improvements in communication before and after the introduction of texting devices to the resident staff (29). The same authors later performed a mixed methods analysis to determine the impact of texting device adoption among internal medicine residents on team effectiveness and communication (30). This subsequent analysis noted several potential problems with PRC texting and texting device use not identified in their earlier work. Residents noted an increase in the numbers of messages and calls received and reported that these interruptions negatively influenced their teaching and PRC communication. Furthermore, nursing staff found that PRC texting reduced opportunities for valued in-person contact and communication. The studies by O’Connor and Wu et al differ significantly from ours (28–30). Their studies focused on internal medicine physician and staff assessments of the effects of texting on overall communication after the introduction of texting devices as an intervention. Our study, by contrast, assessed the prevalence, frequency, and purpose regarding PRC texting among resident and attending surgeons as they currently exist, without the added intervention of introducing institutionally-supported texting devices for research reasons.

The use of non-institutionally supported texting devices may also explain why 22–30% of our surveyed respondents expressed some level of discomfort in using texting for PRC. We purposely left the concept of PRC vague in the survey to maximize the number of responses since PRC can vary significantly based on the hospital setting and the resident, faculty, and service involved. However, one commonality to PRC text messaging is use of patient identifiers and protected health information as defined through the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA). Texting PRC information through personal cell phones is not in itself a violation of HIPAA. The Privacy Rule of HIPAA permits use of protected health information without prior authorization for treatment, payment, or operations. However, in doing so, the PRC information must also be in compliance with the Security Standards set forth by HIPAA. These standards require hospitals and providers to: 1) ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of patient health information transmitted; 2) identify and protect against reasonably anticipated threats to the security of the information; 3) protect against reasonably anticipated impermissible uses or disclosures; and 4) ensure compliance by their workforce. While texting pagers are provided by our institution and utilize a secure network, text messages sent via personal cell phones may violate HIPAA Security Standards. Personal cell phones utilize unsecure networks, are not encrypted, and often store data on a smart phone computer or SIM card which can be accessed by unwanted parties should the phone be lost or stolen. Our intent was to document and promote awareness of current practices and to promote clarification or changes in hospital wide policy reqarding personal cell phone usage to facilitate physician to physician communication.

While our survey response rate was quite good at 65%, many respondents did not answer all questions. This may have been particularly important when attempting to define differences between surgery and resident staff with respect to texting habits. While we did note some differences between resident and attending staff, our respondent numbers may have been too small to detect smaller differences between these two groups. It is unclear if our findings are applicable to other general surgery programs across the country. We believe our general surgery residency, one of the largest in the country, is fairly representative. The program provides a diverse range of hospital environments. In addition to a tertiary care academic medical center, our residents train in a children’s hospital, a large health maintenance organization, a private community setting, a Veteran’s facility and an active duty military hospital. We believe that our survey of residents and faculty serving in these diverse facilities provides a true picture of the national status of general surgery in all its various settings.

As texting increases in prevalence among physicians, data such as ours will facilitate the development of guidelines for the appropriate use of PRC texting. Additionally, our data suggest that future studies are needed to assess the role of PRC texting among other medical specialties and the role it plays in altering patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the resident and attending surgery staff at UC Davis Medical Center and its affiliates for their cooperation and participation in this survey.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster presentation at both the University of California Davis Quality Improvement Symposium March 3, 2012 in Sacramento, California and The Translational Science 2012 Meeting April 18-20, 2012 in Washington, DC.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brown J, Shipman B, Vetter R. SMS: The Short Message Service. Computer. 2007;40:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith A. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; 2011. Americans and text messaging; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville R, Greene A, McLeod J, et al. Mobile phone text messaging can help young people manage asthma. BMJ. 2002;325:600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.600/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Hart T, Chesser A, et al. Content of text messaging immunization reminders: what low-income parents want to know. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baptist AP, Thompson M, Grossman KS, et al. Social media, text messaging, and email-preferences of asthma patients between 12 and 40 years old. J Asthma. 2011;48:824–830. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.608460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelius JB, St Lawrence JS. Receptivity of African American adolescents to an HIV-prevention curriculum enhanced by text messaging. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2009;14:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dick JJ, Nundy S, Solomon MC, et al. Feasibility and usability of a text message-based program for diabetes self-management in an urban African-American population. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5:1246–1254. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber BS, Stolley MR, Thompson AL, et al. Mobile phone text messaging to promote healthy behaviors and weight loss maintenance: a feasibility study. Health Informatics J. 2009;15:17–25. doi: 10.1177/1460458208099865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haug S, Meyer C, Dymalski A, et al. Efficacy of a text messaging (SMS) based smoking cessation intervention for adolescents and young adults: Study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 12:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang F, Liu SC, Shih SM, et al. A Web-based short messaging service system to enhance family-centered surgical patient care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;122:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juzang I, Fortune T, Black S, et al. A pilot programme using mobile phones for HIV prevention. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:150–153. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kew S. Text messaging: an innovative method of data collection in medical research. BMC Res Notes. 3:342. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad S, Anand R. Use of mobile telephone short message service as a reminder: the effect on patient attendance. Int Dent J. 62:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz LI, Detsky AS. Physician communication in the 21st century: to talk or to text? JAMA. 2011;305:1128–1129. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Commission TJ; TJ Commission. Sentinel Event Data Root Causes by Event Type 2004-Third Quarter 2011. Washington, DC: The Joint Commission; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beebe SA. Nurses’ perception of beeper calls. Implications for resident stress and patient care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:187–191. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170140069011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickam DH, Severance S, Feldstein A, et al. The effect of health care working conditions on patient safety. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2003:1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76:801–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Karsh BT. Interruptions and distractions in healthcare: review and reappraisal. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:304–312. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.033282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bush H. Technology. Cutting-edge portable devices raise concerns. Hosp Health Netw. 2007;81:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knox C, Smith A. Handhelds and HIPAA. Nurs Manage. 2007;38:38–40. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000277006.44416.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denizard-Thompson NM, Feiereisel KB, Stevens SF, et al. The Digital Divide at an Urban Community Health Center: Implications for Quality Improvement and Health Care Access. Journal of Community Health. 2011;36:456–460. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junco R, Merson D, Salter DW. The effect of gender, ethnicity, and income on college students’ use of communication technologies. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:619–627. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samal L, Hutton HE, Erbelding EJ, et al. Digital divide: variation in internet and cellular phone use among women attending an urban sexually transmitted infections clinic. J Urban Health. 2010;87:122–128. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9415-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hensel BK, Fontelo P. Physician attitudes toward SMS/Text messaging in medicine. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiegelman J, Detsky AS. Instant mobile communication, efficiency, and quality of life. JAMA. 2008;299:1179–1181. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soto RG, Chu LF, Goldman JM, et al. Communication in critical care environments: mobile telephones improve patient care. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:535–541. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000194506.79408.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connor C, Friedrich JO, Scales DC, et al. The use of wireless e-mail to improve healthcare team communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:705–713. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu RC, Morra D, Quan S, et al. The use of smartphones for clinical communication on internal medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:553–559. doi: 10.1002/jhm.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu R, Rossos P, Quan S, et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed-methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e59. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]