Abstract

Objectives

Root canal treatment forms an essential part of general dental practice. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is the most commonly used irrigant in endodontics due to its ability to dissolve organic soft tissues in the root canal system and its action as a potent antimicrobial agent. Although NaOCl accidents created by extrusion of the irrigant through root apices are relatively rare and are seldom life-threatening, they do create substantial morbidity when they occur.

Methods

To date, NaOCl accidents have only been published as isolated case reports. Although previous studies have attempted to summarise the symptoms involved in these case reports, there was no endeavor to analyse the distribution of soft tissue distribution in those reports. In this review, the anatomy of a classical NaOCl accident that involves facial swelling and ecchymosis is discussed.

Results

By summarising the facial manifestations presented in previous case reports, a novel hypothesis that involves intravenous infusion of extruded NaOCl into the facial vein via non-collapsible venous sinusoids within the cancellous bone is presented.

Conclusions

Understanding the mechanism involved in precipitating a classic NaOCl accident will enable the profession to make the best decision regarding the choice of irrigant delivery techniques in root canal débridement, and for manufacturers to design and improve their irrigation systems to achieve maximum safety and efficient cleanliness of the root canal system.

Keywords: central venous pressure, ecchymosis, facial vein, intraosseous space, positive fluid pressure, root canal treatment, sodium hypochlorite

1. Introduction

Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is routinely used in root canal treatment as a chemical adjunct to mechanical débridement of the root canal system.1,2 It is an excellent irrigant in terms of its ability to function as a lubricant during biomechanical preparation of the root canals, and to dissolve pulpal tissues and the organic components of the smear layer.3 The free chlorine released by NaOCl in the form of hypochlorite ions also enables it to functional as an excellent antimicrobial agent against microbiota and viruses by irreversibly oxidising their enzymes.4 With prolonged application, NaOCl is also anti-fungal against Candida species, although it may not readily dissolve their ! -glucan cell wall.5 Sodium hypochlorite is also very effective for flushing and displacing loose débris inside the canal space, but the apical extent of its effectiveness is a function of the depth of insertion of the irrigation needles.6,7 Sodium hypochlorite is highly alkaline (pH 11 – 12.5) and is a strong oxidising agent of proteins.8 Complete haemolysis of red blood corpuscles occurred when they came into contact in vitro with NaOCl at dilutions as low as 1:1000 (prepared from 5.25% full-strength bleach). Placement of undiluted and 1:10 dilutions of NaOCl on the cornea of rabbits resulted in moderate to severe irritation that healed after 24 to 48 hours. Intradermal injections of undiluted, 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 dilutions of NaOCl produced painful skin ulcerations but no ecchymosis.9 These disturbing in vitro results had actually been observed in actual accidents that occurred to the eye and skin in patients undergoing root canal treatment.10,11 In addition, very low concentrations of NaOCl (>0.01%) were found to be lethal to human fibroblasts in in vitro cell cultures.12 Injection of NaOCl into canine femurs ex vivo also resulted in compromising the integrity of cancellous bone and degradation of its collagen organic matrix.13 Likewise, the microstructure, organic content, and mechanical strength of bovine cancellous bone were dramatically altered at the bone surface after NaOCl treatment.14 Thus, if used injudiciously, NaOCl is very toxic and destructive to intraoral soft tissues, the periradicular vasculature and cancellous bone where it can elicit severe inflammatory responses and degradation of the organic components of these tissues.

Ideally, irrigants should be confined to the root canal system during root canal treatment. This is not always possible, however, as extrusion of irrigants, including NaOCl, beyond the apical foramen may occur during over-instrumentation, in teeth with open apices,15 and through sites of external resorption or perforation along the cavity walls.16–21 Binding of the irrigation needle tip inside a canal and use of too much irrigation pressure may also result in extrusion of irrigant into the periradicular tissues, leading to tissue destruction and necrosis.22 When used as a root canal irrigant, it is essential that NaOCl is prevented from entering the periradicular regions, injecting into the maxillary sinus or soft tissue spaces, which may result in severe and often life-threatening NaOCl accidents.

A survey conducted on 314 diplomates of the American Board of Endodontics indicated that only 132 members reported experiencing a NaOCl accident.20 In that survey, significantly more female patients experienced NaOCl accidents compared with males, with the rationale being the decrease in bone thickness and density in the former sex group. The condition occurred mostly in maxillary teeth versus mandibular teeth, and more often involved posterior teeth instead of anterior teeth, because of the closer proximity of the roots to the buccal bone surface. Patients’ signs and symptoms generally resolved within a month. The authors concluded that NaOCl accidents are relatively rare and that they could be caused by additional factors such as anatomical variations or communication with fascial spaces through fenestrations of the root tips through the overlying bone, rather than by faulty irrigation alone.

2. Types of NaOCl Accidents

Three types of NaOCl extrusion accidents have been reported in the literature: careless iatrogenic injection, extrusion into the maxillary sinus, and extrusion or infusion of NaOCl beyond the root apex into the periradicular regions.

2.1 Careless iatrogenic injection

Hermann et al. reported a case in which an anaesthetic carpule consisting of 1.8 mL of 5.25% NaOCl was inadvertently used for a mandibular block and injected into the pterygomasseteric space and the inferior dental nerve.23 The injection resulted in massive oedema involving the pterygomandibular space and the peritonsillar and pharyngeal areas, as well as immediate trismus. Likewise, Gursoy et al. reported a case in which NaOCl was inadvertently injected into the palatal mucosa in lieu of local anaesthetic solution, resulting in ulceration and necrosis of the palatal mucosa but without bony involvement.24 There was no facial ecchymosis associated with both of these case reports.

2.2 Extrusion of NaOCl into the maxillary sinus

Inadvertent injection of NaOCl into the maxillary sinus has been described in three case reports with complications varying from inconsequential,25 to complaint of burning sensation and accompanying nasal bleeding,26 to severe facial pain requiring hospitalisation and operative intervention under general anaesthesia.27 A possible reason for NaOCl extrusion into the maxillary sinus was provided by Hauman et al. in their review, stating that the alveolar bone becomes thinner with ageing, particularly in areas surrounding the tooth apices.28 In such cases, the root tips projecting into the sinus are covered only by a thin bony lamella and the sinus membrane and there would be minimal resistance to flow of irrigants into the maxillary sinus. Recently, Khan et al. reported apically-directed pressures of 2.6 mm of Hg using an unbound side-vented needle with a flow rate of 1 mL/min positioned at 1 mm from working length.29 In an earlier study, Jiang et al. used a higher flow rate of 6 mL/min with needles in the same position,30 in which case the apically-direct pressure would have been 72 mm Hg.29 In either case, sufficient irrigation pressure would cause extrusion of NaOCl into the maxillary sinus if the Schneiderian membrane was missing. Sleiman31 reported complaints by a female patient referred for evaluation of the upper right first molar, who experienced the smell of chlorine in her throat arising from her nose. Although extrusion of NaOCl into the maxillary sinus could not be ascertained, cone-beam computed tomography of the maxilla showed that the right maxillary sinus was filled with inflammatory tissues and that the posterior wall of the sinus was non-existent in some places. The tomography data suggested that the position of the patient during root canal therapy might have produced stagnation of NaOCl, initially along the thin bony wall of the sinus and eventually resulted in seepage of the NaOCl into the sinus. Nevertheless, signs of facial ecchymosis were not apparent in all these cases of NaOCl extrusion.

2.3 Infusion of NaOCl beyond the root apex into the periradicular regions

By far, the majority of case reports on NaOCl accidents fall into this category. Becker et al.22 and Sabala and Powell32 were among the first to report incidences of forceful injection of NaOCl into the periapex tissues beyond the apical foramen. Both studies reported injection of as little as 0.5 mL of NaOCl into the periapical tissues. It is explicable at that time how extrusion of such a small amount of NaOCl into the periradicular tissues could have resulted in inflammation and destruction of soft tissues of unproportional magnitude. For example, Sabala and Pewell32 attributed the cause of the accident to angioneurotic oedema with histamine release, without providing any physiological rationale responsible for the disproportionate ecchymosis that occurred. Indeed, extensive ecchymosis occurred around the left periorbital region of the eye, the angle of the mouth and the neck, which was far away from the apex of the maxillary left second premolar, in which extrusion of NaOCl beyond the root apex occurred during root canal treatment. In that case, there was no subcutaneous ecchymosis associated with the apex of the maxillary left second premolar. For ecchymosis to have occurred to such an extent, there should have been damage to the blood vessels with extravascation of blood into the adjacent subcutaneous soft tissues. Thus, attributing these events to angioneurotic oedema with histamine release alone may have created a myopic view of the mechanism causing a devastating NaOCl incident.

Subsequent case reports also described similar effects of inadvertent injection of NaOCl into the periradicular region, which resulted in immediate severe pain with burning sensation, progressive swelling and oedema. Haematoma and ecchymosis of the facial skin could occur immediately or after a few hours, both interstitially and through the tooth, and accompanied by tissue necrosis and, at times, paraesthesia. The majority of cases resolve within several weeks after the accident.

Spencer et al. categorised the complications arising from NaOCl infusion beyond the root apex into three categories:33

Chemical burns and tissue necrosis, which include tissue swelling that may be oedmatous,34–38 haemmorrhagic,39,40 or both,40–42 and may extend beyond the region that may be expected with an acute infection of the affected tooth.39–45 Pain, which is the hallmark of tissue damage, may be experienced immediately or be delayed for several minutes or hours.

Neurological complications, which may include paraesthesia and anaesthesia affecting the mental, inferior dental and infraorbital branches of the trigeminal nerve that may take many months to completely resolve.16,46,47 In addition, facial nerve damage including the buccal branch of the facial nerve may be involved.15,48,49 Nerve damage caused by NaOCl can be irreversible, resulting in permanent loss of sensory47 or motor function.15

Upper airway obstruction. Although there were several reports on upper airway obstruction caused by direct ingestion of NaOCl, there was only one study reporting a direct cause and effect relationship between NaOCl extrusion during root canal treatment of a lower left second molar and extensive swelling of the submandibular, submental and sublingual tissue spaces (i.e. Ludwig’s angina), with marked elevation of the tongue, that ultimately resulted in upper airway obstruction.50 The case was resolved by hospitalisation in intensive care, and urgent surgical decompression of the tissue spaces with surgical placement of bilateral through-and-through drains, as well as removal of the involved tooth.

3. An Example of a Classical Case of NaOCl Extrusion Beyond the Root Apex

Because the literature is sparse with respect to the first two types of NaOCl accidents, the rest of the review will concentrate on the third and most common type of NaOCl accidents that are often presented in lectures and textbooks. Although neurological complications may be present, these classical cases are visually disturbing, not so much from the accompanying oedema, as the latter may be the sequelae of intraoral surgical procedures involving the raising of a mucoperiosteal flap, but from the pathognomonic appearance of extensive facial ecchymosis, irrespective of the location of the tooth in which NaOCl extrusion occurs. This is illustrated by a relatively mild case of NaOCl accident that occurred in the Department of Endodontics, Georgia Regents University College of Dental Medicine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A classical sodium hypochlorite accident showing the time course of facial involvement from onset to resolution. A. Immediately after removal of rubber dam. Ecchymosis visible along corner of the mouth (arrow) and lower eye lid (open arrowhead). No facial oedema. B. Three hours after onset of the accident. C. After 24 hours. Swelling resulted in the disappearance of the nasolabial fold (open arrow) and Marionette lines (open arrowhead)) on the right side of her face. D. After 48 hours. E. After 4 days. F. A 3 weeks.

A 52-year-old female with non-contributory systemic conditions and taking estradiol for hormonal replacement therapy was referred to the endodontic clinic for root canal treatment of tooth 14 (upper right first premolar). The tooth was previously used as the abutment of a 3-unit fixed prosthesis involving teeth 14 and 16 (upper right first molar) as abutments. After the fixed prosthesis was removed, core replacement for tooth 14 resulted in the penetration of a retention pin into the pulp chamber. Initial attempt to perform root canal treatment on tooth 14 in the restorative dentistry clinic was unsuccessful in identifying all canals. Upon examination in the endodontic clinic, tooth 14 was diagnosed as previously initiated with normal periapex. After receiving consent for non-surgical root canal treatment, tooth 14 was anaesthetised with infiltration anaesthesia and isolated with rubber dam. The buccal and palatal canals were identified and shaped to size 35, 0.04 taper using stainless steel hand files and nickel titanium rotary instruments. During irrigation of the canals with 5.25% NaOCl using a beveled, open-ended needle, the patient experienced burning sensation over her right face. The irrigant was aspirated and the canals were flushed copiously with sterile saline. The patient reported relief at that point and root canal treatment was subsequently completed with re-cementation of the provisional fixed prosthesis.

On removal of the rubber dam, ecchymosis was evident along the corner of the mouth; mild ecchymosis was also noted around the lower periorbital region of the right side of the face. There was minimal oedema and facial swelling at this stage (Figure 1A). The patient was informed of the presence of a NaOCl accident and the possible sequelae of delayed oedema and facial swelling. She was given an ice pack that could be activated on demand to alleviate pressure caused by subsequent swelling. In addition, hydrocodone/acetaminophen (5mg/500mg) was prescribed three times a day for 7 days to relieve pain, together with amoxicillin (500 mg) three times per day for 7 days to prevent bacterial infection, and methylprednisolone (4 mg) three times a day for 7 days to relieve swelling. She was also instructed to return daily for the subsequent three days for monitoring the course of the NaOCl accident.

The patient reported onset of facial swelling 3 hours after leaving the operatory (Figure 1B); the oedema and swelling increased progressively within the subsequent 24 hours (Figure 1C). The swelling resulted in the disappearance of the nasolabial fold and Marionette lines (oral commissures) on the right side of her face. The patient’s face remained swollen at 48 hours (Figure 1D). Regression of the condition began on the fourth day (Figure 1E), and normal tissue appearance and absence of sequelae were observed after 3 weeks (Figure 1F).

4. Pathognomonic Appearance of NaOCl Infusion into Periradicular Tissues

A search of the dental and medical literature identified many case reports of accidental apical or lateral extrusion of NaOCl into the periradicular tissues, with images of panfacial oedema and ecchymosis that bear striking resemblance to the aforementioned example (Figure 2). This list is not intended to be exhaustive; readers may wish to refer to Table 4 in the review by Hülsmann et al.40 for a comprehensive listing of case reports on NaOCl extrusion into the periradicular tissues between 1974 and 2007. Nevertheless, Figure 2 serves to illustrate the increasing order of severity of panfacial involvement that may accompany these classic NaOCl accidents. They may be classified into four categories:

Oedema only without ecchymosis (Figures 2A40, 2B38);

Ecchymosis involving the angle of the mouth and the periorbital region (Figures 2C21, 2D40, 2E49, 2F52, 2G41, 2H49, 2I44, 2J53, 2K42, 2L54);

Ecchymosis involving II and extending extensively into the neck region (Figures 2M46, 2N, 2O55, 2P40, 2Q32, 2W51);

Ecchymosis involving III and extending into the chest, resulting in mediastinal ecchymosis (Figures 2R40, 2S39, 2T56, 2U, 2V)

Figure 2.

A composite image showing facial photographs of sodium hypochlorite accidents reported in the literature as well as contributed by one of the authors. (2A reprinted from Hülsmann et al.40, with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2B modified from Behrents38 with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2C reprinted from Wang et al.21, with permission from Bentham Science Publishers; 2D, 2P and 2R modified from Hülsmann et al.40, with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2E and 2H modified from Witton et al.49, with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2F modified from Paschoalino Mde et al. 52, with permission from the Academy of General Dentistry; 2G modified from Tosti et al.41, with permission from the American Dental Association; 2I modified from Lee et al. 44, with permission from the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; 2J modified from Oreadi et al.53, with permission from Dr. Papageorge and the Massachusetts Dental Society; 2K reprinted from Mehra et al.42, with permission from the American Dental Association; 2L modified from Crincoli et al.54, with permission from Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc.; 2M modified from Becking46, with permission from Elsevier; 2O reprinted from Torabinejad et al.55, with permission from Elsevier; 2Q modified from Sabala et al.32, with permission from Elsevier; 2S modified from de Sermeño et al.39, with permission from Elvesier; 2T modified from Joffe E56, with permission from the Academy of General Dentistry; 2W modified from Gernhardt et al.51, with permission from John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2N, 2V and SU courtesy of Dr. Filippo Santarcangelo.)

The first category (oedema) may be perceived as a protective tissue response when a hyperosmotic and cytotoxic liquid is extruded into the vicinity of periradicular tissues. The other categories with increasing extent of ecchymosis invariably involve dissolution of blood vessel walls and haemorrhage around the subcutaneous soft tissues. These manifestations are not surprising, as NaOCl is extremely cytotoxic, a potent solvent for organic materials. It is also a very powerful oxidant and the mechanism of injury from undiluted NaOCl is primarily oxidation of proteins. Depending on the concentration employed for root canal irrigation, NaOCl may also be very hypertonic (~2800 mOsm/Kg for 3–6% solutions) with respect to tissue fluids; this partially accounts for the rapid appearance of oedema during a NaOCl accident. What is surprising is the similarity in the locations at which ecchymosis was manifested in those cases, and the absence of ecchymosis in the soft tissues immediately superficial to the apical termination of the tooth involved in NaOCl extrusion. To date, NaOCl accidents have only been published as isolated case reports. Although previous reviews have attempted to summarise the symptoms involved in these case reports,33,40 there was no endeavor to analyse the distribution of the ecchymosis. When these cases are viewed together as a series, it becomes readily apparent that ecchymosis is universally present along the angle of the mouth, and around the periorbital region (i.e. upper and/or lower eyelids) most of the time. Most of these cases are presented with an area along the lateral the side of the nose in which ecchymosis is absent. The only two exceptions are: a) Figure 2P, where there is uninterrupted line of ecchymosis along the lateral side of the nose that connects the subcutaneous ecchymosis in the periorbital region to that along the angle of the mouth; and b) Figure 2U, where there is only a small area lateral to the ala of the nose that is devoid of ecchymosis. Inclusion of these two “exceptions” enables the readers to have an easier appreciation that ecchymosis is consistently manifested along the course of superficial venous vasculature.

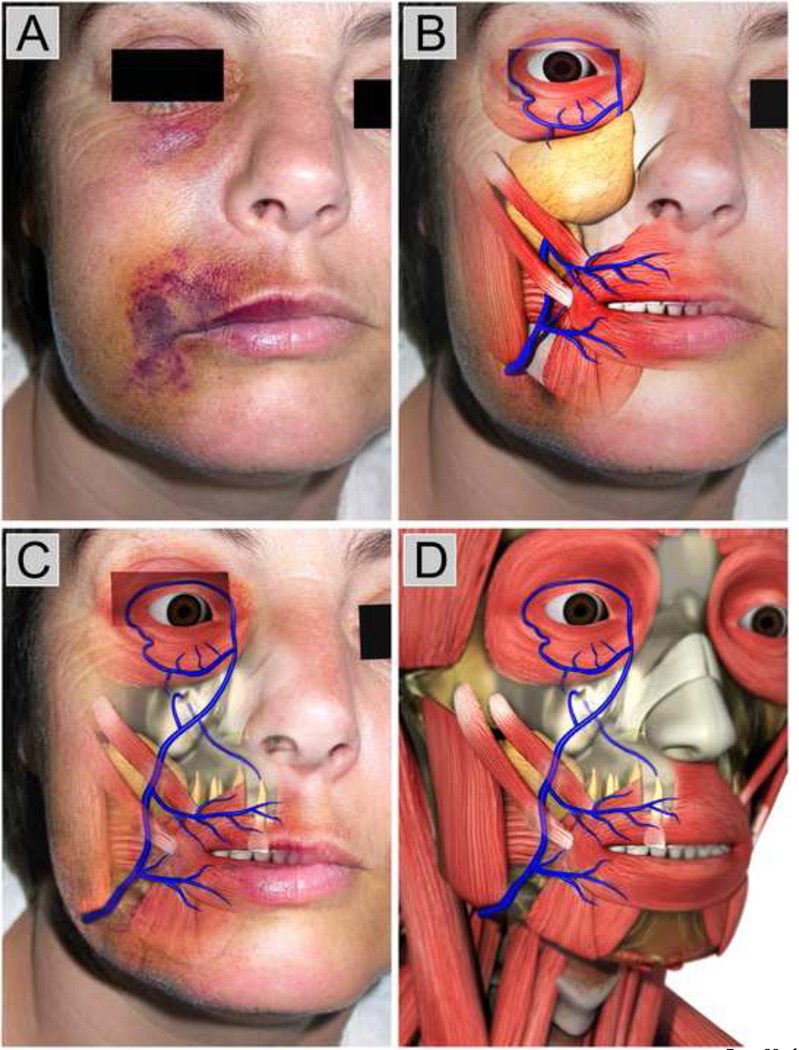

Figure 3A shows the pathognomonic appearance of another classical NaOCl accident in which NaOCl was extruded from the apex of a right maxillary lateral incisor and infused into the periradicular tissues.48 The “digital dissections” in Figures 3B–3D illustrate why the tissues immediately superficial to the tooth’s apical termination is not ecchymotic, and yet the upper and lower eyelids and angle of the mouth clearly demonstrate bruising, but with an unaffected area between those two regions. The superior and inferior palpebral (eyelid) veins connect to the angular vein near the medial angle of the eye. The angular vein connects to the anterior facial vein at the inferior margin of the orbit, which proceeds down the midface. Shortly after confluence with the angular vein, the anterior facial vein is covered by the zygomatic muscles, associated adipose tissue and the malar fat pad. Thus, any hemorrhage in this deep area is usually masked by these different tissue layers. In rare circumstances when the anterior facial vein runs superficially along the lateral side of the nose, the entire course of this vein may become ecchymotic (Figures 2P, 2U). The anterior facial vein becomes very superficial again at the angle of the mouth where it receives the superior and inferior labial veins. Thus, ecchymosis reappears at the angle of the mouth and both lips. Inferior to the margin of the mandible, the anterior facial vein unites with the anterior branch of the retromandibular vein (not shown) to form the common facial vein, which drains into the internal jugular vein at the level below the hyoid bone. From near the termination of the common facial vein, a communicating branch often runs down the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoideus muscle to join the lower part of the anterior jugular vein in the neck.57 Thus, depending on the amount and concentration of NaOCl entering the venous complex, as well as the specific location of the venous elements and associated tissues, the extent of the ecchymosis would vary. In more severe cases, ecchymosis may extend into the side neck and the chest (e.g. Figure 2T).

Figure 3.

A. Original photograph of a classic sodium hypochlorite accident taken from Witton and Brennan,48 showing ecchymotic involvement of the eyelid and the angle of the mouth (3A reprinted with permission from the Nature Publishing Group). B. Superficial “digital dissection” based on Figure 3A, showing the superior and inferior palpebral veins and the superior and inferior labial veins. The facial vein in the middle third of the face is covered by the malar fat mad, associated adipose tissues and the zygomatic muscles. C. “Digital dissection” of the adipose tissues enables the underlying facial vein to be reviewed. An anatomical anomaly is presented in which the venule from top apical foramen of the upper right lateral incisor drains directly into the facial vein. D. Further “digital dissections” of the facial skin reveals the course of the facial vein and its tributaries in relation to the muscles of the face and neck. (3B–3D reprinted with permission from SybronEndo, Carlsbard, CA, USA).

Deviation from the normal pattern in the vascular system is a common feature and is more common in the veins than in the arteries.58 For example, most of the ecchymotic cases seen in Figure 2 are unilateral and the nose is rarely involved because there is usually no communication between left and right anterior facial vein. However, when the left and right anterior facial veins communicate via the external nasal veins along the bridge of the nose, ecchymosis may involve the contralateral periorbital region (Figures 2K, 2S and 2U).

4.1 Why are Classic NaOCl Accidents So Rare?

While it is undeniable that ecchymosis in a classic NaOCl accident is consistently manifested along the course of panfacial superficial venous vasculature, it remains to be discussed why these accidents so rare (less than 50 cases in the literature published between 1974–2013), despite millions of root canal therapy performed annually using NaOCl irrigation.

Table I lists the teeth involved in the ecchymotic cases presented in Figure 2. With the exception of case 2F, teeth that are associated with the other NaOCl accidents include the central and lateral incisors, canine, first and second premolars. Although maxillary teeth are predominantly involved, there are two cases in which the NaOCl accident occurred in mandibular premolars (Figures 2R and 2W). Venous drainage of the teeth is highly variable. In the maxilla, venules from the teeth and alveolar bone pass into larger veins in the interdental septa, which drain into the anterior and posterior superior alveolar veins. These veins usually drain posteriorly into the pterygoid plexus, a collection of small anastomosing vessels within the infratemporal fossa, although some drainage from the anterior teeth may be via tributaries of the facial vein.59 The pterygoid plexus drains into the maxillary vein and ultimately via the retromandibular vein into the jugular system of veins. In the mandible, venules from the lower teeth collected to one or more inferior alveolar veins that drain through the mental foramen into the pterygoid plexus.60 Occasionally, these venules drain to the inferior labial vein and the submental vein and back to the anterior facial vein,61 thus validating the appearance of Figures 2R and 2W.

Table I.

Teeth involved in NaOCl extrusion in Figure 2. Only cases exhibiting facial ecchymosis are included

| Figures | Tooth involved |

|---|---|

| 2C | Maxillary left canine |

| 2D | Maxillary left canine |

| 2E | Maxillary right second premolar |

| 2F | Maxillary left third molar |

| 2G | Maxillary left first premolar |

| 2H | Maxillary right lateral incisor |

| 2I | Maxillary left central incisor |

| 2J | Maxillary left first premolar |

| 2K | Maxillary left retained primary canine |

| 2L | Maxillary right canine |

| 2M | Maxillary left first premolar |

| 2N | Maxillary right first premolar |

| 2O | Maxillary right canine |

| 2P | Maxillary right canine |

| 2Q | Maxillary left second premolar |

| 2R | Mandibular left second premolar |

| 2S | Maxillary right canine |

| 2T | Maxillary left canine |

| 2U | Maxillary left first premolar |

| 2V | Maxillary left first premolar |

| 2W | Mandibular left first premolar |

To understand why classic NaOCl accidents are rare, it is pertinent to point out that several conditions have to exist simultaneously for a full-blown, ecchymotic NaOCl accident to occur. They include:

The apical foramen of the involved tooth has to be rendered patent for infusion of NaOCl into the periradicular tissues;62 Patency filing is a canal preparation technique where the apical portion of the canal is maintained free of débris by recapitulation with a small file through the apical foramen. Apical patency refers to the ability to pass a small size. 6–10 K-file through the apical foramen to ensure that the canal is predictably negotiable. Although patency filing has distinct advantages,63 and enhances irrigant penetration into the apical 2 mm of large root canals,64 it is also associated with a higher incidence of NaOCl extrusion through the apical foramen.65 Thus, there is still controversy within the endodontic profession with respect to the adoption of patency filing.66

An anatomical variation has to exist for drainage of the infused NaOCl directly into the anterior facial vein to result in subcutaneous facial haemorrhage. Blood from the maxillary and mandibular teeth drains predominantly into the pterygoid plexus. However, anatomical variations are common with the facial venous vasculature and occasionally, drainage from the anterior teeth occurs via tributaries of the anterior facial vein. Although the facial vein communicates with the pterygoid plexus via one of its tributaries, the deep facial vein, once the blood drains directly from the teeth into the pterygoid plexus, it is unlikely to backflow into the facial vein due to the relative size of the veins and cross sectional areas. Although valves are present within the facial vein which prevents the back flow of blood, sometimes they are absent.67 Moreover, all venous valves are designed by nature to resist only a back flow of a few millimeters of mercury pressure, far less than the pressures to be discussed shortly.

The apically pressure generated by positive-pressure irrigation delivery systems at the periapex have to exceed the venous pressure in the superficial veins of the neck. Traditional beliefs maintain that wedging an irrigation needle in the canal is the only way to produce high enough pressure to produce a NaOCl incident. However, only 20% of diplomates of the American Board of Endodontics attributed this phenomenon to the cause of a NaOCl incident.20 Moreover, it has been shown that irrigating solutions could clinically reach the periapical tissues even in the absence of a forceful injection.68 Computation fluid dynamic studies have demonstrated that most positive pressure irrigant delivery systems have to be placed as close as possible to the apical seat, without binding, to eliminate the fluid stagnation plane beneath the device for effective irrigant delivery.69–72 By doing so, an apical fluid pressure is generated by all these needles and devices. When this apical fluid pressure exceeds the venous pressure of the facial veins, the possibility exists for the irrigant to be infused into a portal of entrance in the facial venous vasculature. The superficial veins of the neck are often used for cannulation, either for intravenous infusion or for monitoring the central venous pressure.73Compared to the normal mean arterial pressure (70–110 mm Hg), the normal central venous pressure has a much lower mean value (1–7 mm Hg; mean = 5.88 mm Hg)74,75 in the supine position. It is even lower when the head is elevated above the heart. Based on the perspective of pressure gradient alone, it is logical that extruded NaOCl will be infused through the path of least resistance into a vein.

The magnitude of apical fluid pressure within the root canal space is affected by the flow rate in which an irrigant is delivered, as well as the type of needle or positive pressure delivery systems employed. Park et al.76 reported that when different types of positive pressure irrigation needles were placed at 3 mm from the working length, the apical pressures generated by needle delivery of 3% NaOCl increased with flow rates, and ranged irrigation pressure-flow rates from 0.34 mm Hg (flow rate = 1 mL/min) to 52.43 mm Hg (flow rate > 8 mL/min). When the needles were placed at 1 mm from the root apex, the apical pressures increased, ranging from 0.38 mm Hg (flow rate = 1 mL/min) to 87.26 mm Hg (flow rate > 8 mL/min). Likewise, Khan et al.29 also reported that apical fluid pressure increased with fluid flow rates. For example, when a 30-gauge side-vented needle was used to deliver 5.25% NaOCl in a non-binding simulated root canal, the apical pressure increased nonlinearly from 2.60 mm Hg at a flow rate of 1 mL/min to 117.20 mmHg at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. By contrast, another positive pressure irrigant delivery device generated much higher apical pressures, ranging from 36.15 mm Hg at a flow rate of 1 mL/min to 544.1 mm Hg at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. Taken together, the results of these two recent studies indicate that given a high enough fluid flow rate, any commercially available positive pressure irrigant delivery device is capable of generating apical pressures in excess of the central venous pressure, with pressure gradients that are high enough for extruded NaOCl to be infused into the facial venous vasculature. This will be further elaborated in the next section. The rate of irrigant delivery by clinicians has been shown to be highly variable, ranging from 1.2 to 48 mL/min for 30-gauge side-vented needles.77 Although more “heavy-handed” clinicians may have a higher probability of creating the pressure gradients necessary for extruding NaOCl into the periradicular tissues, a NaOCl accident will not occur unless the apical foramen of the root is rendered patent and in the presence of an anatomical variation of the pattern of venous drainage.

5. Intravenous Infusion of NaOCl

Despite the rare incidence of NaOCl accidents, their occurrence produce damages that can result in serious morbidity that are as devastating as the spectrum of NaOCl toxicity identified in humans.78 An important issue that further needs to be addressed is why extrusion of NaOCl from teeth present in different locations of the mouth invariably results in the same pathognomonic ecchymosis pattern, albeit of different intensities, along the course of the facial vein, whereas the soft tissues immediately superficial to the apical termination of the involved tooth remain unaffected. This issue has to be addressed by first understanding that these accidents are the consequence of direct intravenous NaOCl infusion and not passive diffusion of NaOCl from the periradicular tissues around the involved tooth to the subcutaneous tissues along the course of the facial venous vasculature.

Injuries caused by intravenous injection of NaOCl have been reported in haemodialysis accidents, in disinfection of venipuncture sites by intravenous drug users or in suicidal attempts. These injuries resulted in severe hemolysis, acute kidney injury, venous thrombosis or cardiac arrest.79–82 These episodes involve injection of NaOCl directly into a superficial vein via the use of a needle or through a catheter (Figure 4A). For direct injection of NaOCl into a vein, there must be an open, non-collapsed vessel and a gradient between the extravascular and intravascular pressure. In these episodes, the superficial veins are not cut and hence do not collapse.

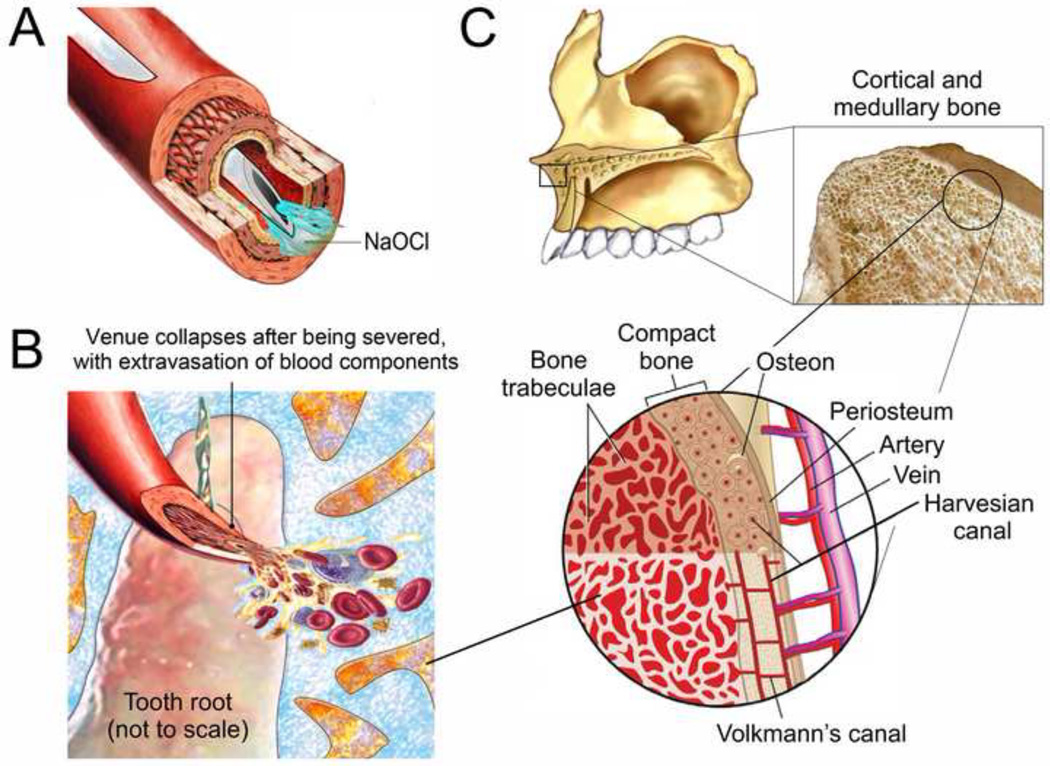

Figure 4.

A. Direct injection of NaOCl into a superficial vein via venipuncture. The vein does not collapse. B. Collapse of a severed venule after it is cut by an endodontic file that extruded out of the apical foramen of the root canal. C. The intraosseous space within the medullary bone contains thousands of tiny non-collapsible interwined blood sinusoids, which drain to the larger veins. Unlike the severed venule depicted in Figure 4B, these tiny sinusoids are supported by the bone trabeculae and do not collapse.

For NaOCl accidents that occur during root canal treatment via extrusion of the irrigant through the root apex, the vascular supply to the tooth or an associated periapical lesion is severed. Because of the loss of intravascular venous pressure and poor venous return, the thin-walled venules collapse once they are severed, with their walls in close apposition after emptying their contents into the surrounding tissues (Figure 4B). Direct injection of NaOCl into collapsed venules is therefore not possible. Although there may be hemolysis of the extravasated blood, this occurs within the medullary bone and do not involve the superficial soft tissue venules. This explains why the soft tissues superficial to the apical termination of the involved tooth remain unaffected in a classical NaOCl accident.

Similar to non-collapsing veins (epiploic veins, emissary veins and dural venous sinuses) in which air may enter during venous gas embolism,83 medullary bone that houses the tooth root is essentially a non-collapsible component of the cardiovascular system. The first scientific evidence was provided by Dr. Drinker of Harvard University, who examined the circulation of the sternum and proposed that the intraosseous space be considered a non-collapsible vein.84 He confirmed that substances infuse into the bone marrow was quickly absorbed into the central circulation. The intraosseous space contains thousands of tiny non-collapsible interwined blood sinusoids, which drain to the larger veins in the interdental septum (Figure 4C).85–87 These tiny sinusoids act like a sponge that immediately absorb any fluid coming in contact with them. Blood pressure in the intraosseous space is approximately 30 mm Hg,88,89 approximately one fourth of the systemic blood pressure (this generalization is known as the one-fourth rule).90,91. Thus, infused fluids such as NaOCl will be rapidly transported to the central veins of the body,92–94 and have similar effects as those obtained by intravenous injection directly into the peripheral vascular system.95 This concept provides the rationale for the adoption of intraosseous vascular access for in pre-hospital settings or in-hospital emergencies for administering drugs to patients suffering from shock and trauma, wherein collapse of the peripheral veins preclude the use of venipuncture or even venesection.96–100 Based on the same principles, intraosseous anesthesia is employed in dentistry as a supplementary technique for obtaining rapid, profound pulpal anesthesia when this cannot be achieved via conventional infiltration or block anesthesia.100–102

For teeth, septal veins converge to the superior posterior alveolar vein in the maxilla and the inferior alveolar vein in the mandible, which drain into the pterygoid plexus, and occasionally into the facial vein. As the intraosseous sinusoids are protected by medullary bone, their walls are rigid and are unable to collapse when venous pressure decreases. The intraosseous space blood pressure (~30 mm Hg) is also higher the central venous pressure (1–7 mm Hg). Thus, NaOCl extruded though a patent tooth root foramen, an immature apex or a root canal perforation may easily and rapidly infuse into the facial vein, should there be an anatomic variation in the facial venous vasculature and when the apically-directed fluid pressure gradient exceeds 30 mm Hg. Because the circulation times for fluids administered indirectly by the intraosseous route and directly by intravenous routes are almost identical,103 ecchymosis rapidly appears after NaOCl extrusion through the root apex in a classic NaOCl accident (Figure 1). Since NaOCl extruded through tooth apices are dispersed within the medullary sinusoids, the same pathognomonic ecchymosis pattern along the course of the facial vein will be manifested irrespective of the location of the tooth involved. Although the present work is not related to gas embolism, fatal incidences caused by intravenous air embolism during root canal treatment or dental implant placement for replacing extracted teeth have been reported in the dental literature.104,105 It is pertinent to highlight that a similar mechanism of air infusion through open intraosseous sinusoids has been used to account for the cause of venous air embolism during dental implant surgery in the mandible.105

6. Prevention of a Classic NaOCl Accident

In no discipline does the maxim: ‘first, do no harm’ has greater significance than in endodontics. For a patient to suffer severe morbidity or debilitating injury during root canal treatment is the embodiment of a medical tragedy. The best treatment of a NaOCl accident is to prevent it from happening. Patient safety is paramount when considering intracanal fluid dynamics, including irrigant delivery rate, agitation and exchange, needle design, pressure gradient management, wall shear stress and cleaning efficacy, and ultimately, treatment outcome. Different preventive measures have been recommended in previous reviews to minimise potential complications associated with the use NaOCl.19,33 They include: a) replacing NaOCl with another irrigant; b) using a lower concentration of NaOCl; c) placing the needle passively and avoiding wedging of the needle into the root canal; d) irrigation needle placed 1–3 mm short of working length; e) using a side-vented needle for root canal irrigation; and f) avoiding the use of excessive pressure during irrigation.

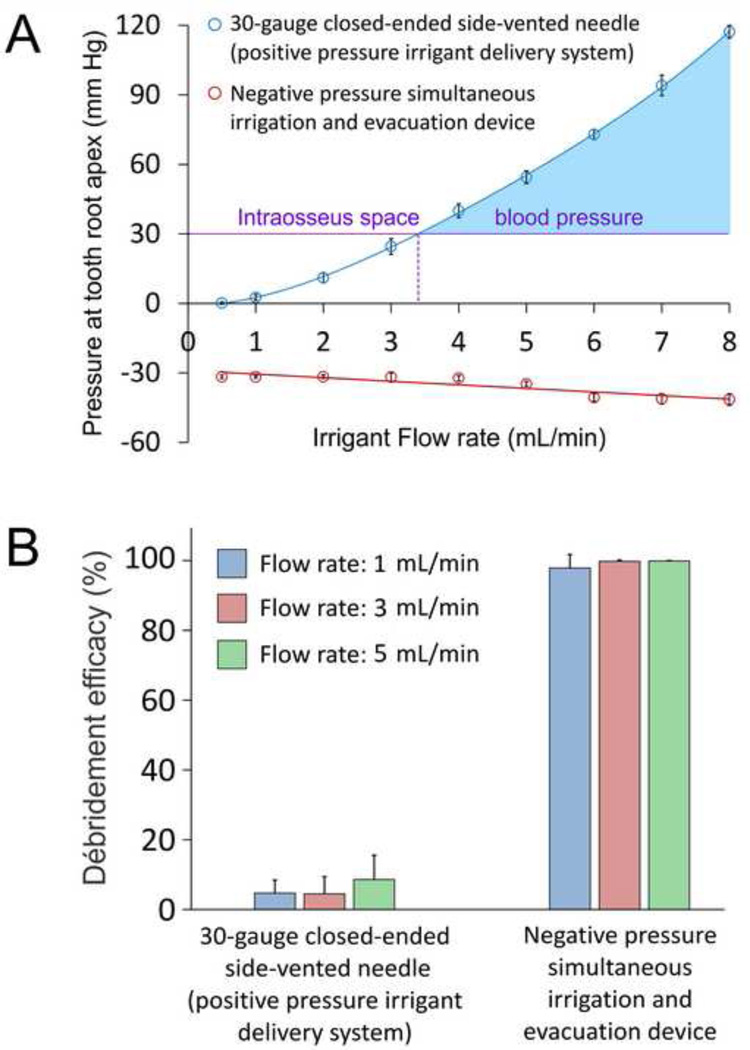

A simulated root canal model has been employed to measure the magnitude of apically-directed fluid pressure associated with the use of different needle delivery systems.29 The use of a non-binding 30-gauge close-ended side-vented needle (a positive pressure irrigant delivery device) inserted to 1 mm short of the working length of root canal preparation results in generating positive fluid pressures at the tooth apex that intensify non-linearly with increasing irrigant flow rate (Figure 5A). When the irrigant flow rate is below 3.4 mL/min, the fluid pressure generated is below the mean intraosseus space blood pressure value of 30 mm Hg. That is, even in the presence of a patent apical foramen and an anatomical variation of the facial venous vasculature, the use of a non-binding side-vented needle with an irrigant flow rate below 3.4 mL/min is unlikely to create a classic NaOCl accident. On the contrary, using the same needle at flow rates beyond 3.4 mL/min has the potential of creating a pressure gradient higher than that of the intraosseous space (blue area), to cause infusion of the extruded NaOCl into a facial vein. By contrast, the use of a commercially available negative apical pressure irrigant delivery needle inserted to full working length of the root canal preparation results in the generation of negative apically-directed fluid pressures that decrease linearly with increasing irrigant flow rates. With the use of this system, the negative fluid pressures generated at all irrigant flow rates never approach the intraosseous blood pressure that is necessary to cause infusion of NaOCl into a facial vein. Thus, an apical negative pressure irrigant delivery device is far safer than positive pressure irrigant delivery systems in terms of the potential in causing harm to a patient during delivery of root canal irrigants.

Figure 5.

A. Changes in apical fluid pressure with irrigant flow rates for a positive pressure irrigant delivery needle and a negative pressure simultaneous irrigation and evacuation device. Data presented are means and standard deviations (N = 10). B. Bar chart showing the ability of the positive pressure irrigant delivery needle and the negative pressure simultaneous irrigation and evacuation device to remove débris from a simulated root canal fin at different flow rates. Data presented are means and standard deviations (N = 10).

That said, there should be a balance between preventing a NaOCl accident and optimal débridement of the root canal space and eradication of intracanal biofilms, particularly from inaccessible areas of the root canal system. Figure 5B represents the results of débridement of calcium hydroxide paste (used to represent tenacious débris) placed in a simulated canal fin in a curved root canal model that is designed to provide a fluid-tight seal, using the protocol described in a recent study.106 Sodium hypochlorite (5.25%) was delivered at irrigant flow rates of 1, 3 and 5 mL/min via a precision syringe pump. The percentage area of residual débris in the canal fin after irrigation was analysed using image analysis. The experiment was designed to simulate a closed canal system wherein irrigants are not allowed to flow continuously from the canal to the external environment. Using this design, the positive pressure side-vented needle did not remove débris efficaciously from the simulated canal fin even when the irrigant flow rates were high enough to create apically-directed fluid pressures that exceeded the mean intraosseus space blood pressure. By contrast, the negative pressure simultaneous irrigation and evacuation needle eliminated débris almost completely at all irrigant flow rates. Thus, an apical negative pressure irrigant delivery system provides the safety features and débridement efficacy necessary to eliminate periradicular periodontitis in contemporary endodontics.

7. Conclusion

Root canal treatment forms an essential part of general dental practice. Sodium hypochlorite is the most commonly used irrigant in endodontics due to its ability to dissolve organic soft tissues in the root canal system and its action as a potent antimicrobial agent. Although NaOCl accidents created by extrusion of the irrigant through root apices are relatively rare and are seldom life-threatening, they create substantial morbidity when they occur. In this review, the anatomy of a classical NaOCl accident that involves facial swelling and ecchymosis is discussed. By summarising the facial manifestations presented in previous case reports, a novel hypothesis that involves intravenous infusion of extruded NaOCl into the facial vein via non-collapsible venous sinusoids within the cancellous bone is presented. Understanding the mechanism involved in precipitating a classic NaOCl accident will enable the profession to make the best decision regarding the choice of irrigant delivery techniques in root canal débridement, and for manufacturers to design and improve their irrigation systems to achieve maximum safety and efficient cleanliness of the root canal system.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant R01 DE015306-06 from NIDCR (PI. David H. Pashley). The authors thank Mrs. Michelle Barnes and Mrs. Marie Churchville for their secretarial support.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest in this review.

References

- 1.Zehnder M. Root canal irrigants. Journal of Endodontics. 2006;32:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedorowicz Z, Nasser M, Sequeira-Byron P, de Souza RF, Carter B, Heft M. Irrigants for non-surgical root canal treatment in mature permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2012;9:CD008948. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008948.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammadi Z. Sodium hypochlorite in endodontics: an updated review. International Dental Journal. 2008;58:329–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siqueira Junior JF, Rocas IN, Favieri A, Lima KC. Chemomechanical reduction of the bacterial population in the root canal after instrumentation and irrigation with 1%, 2.5%, and 5.25% sodium hypochlorite. Journal of Endodontics. 2000;26:331–334. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen BH, Safavi KE, Spångberg LS. Antifungal effects of sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine in root canals. Journal of Endodontics. 1999;25:235–238. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(99)80149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow TW. Mechanical effectiveness of root canal irrigation. Journal of Endodontics. 1983;9:475–479. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(83)80162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Verhaagen B, Versluis M, Kastrinakis E, Wesselink PR, et al. The effect of needle-insertion depth on the irrigant flow in the root canal: evaluation using an unsteady computational fluid dynamics model. Journal of Endodontics. 2010;36:1664–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai SC, Mak YF, Cheung GS, Osorio R, Toledano M, Carvalho RM, et al. Reversal of compromised bonding to oxidized etched dentin. Journal of Dental Research. 2001;80:1919–1924. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800101101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pashley EL, Birdsong NL, Bowman K, Pashley DH. Cytotoxic effects of NaOCl on vital tissue. Journal of Endodontics. 1985;11:525–528. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(85)80197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram TA., 3rd Response of the human eye to accidental exposure to sodium hypochlorite. Journal of Endodontics. 1990;16:235–238. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81678-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serper A, Ozbek M, Calt S. Accidental sodium hypochlorite-induced skin injury during endodontic treatment. Journal of Endodontics. 2004;30:180–181. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200403000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heling I, Rotstein I, Dinur T, Szwec-Levine Y, Steinberg D. Bactericidal and cytotoxic effects of sodium hypochlorite and sodium dichloroisocyanurate solutions in vitro. Journal of Endodontics. 2001;27:278–280. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerbl FM, DeVilliers P, Litaker M, Eleazer PD. Physical effects of sodium hypochlorite on bone: an ex vivo study. Journal of Endodontics. 2012;38:357–359. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi L, Li DC, Huang ZS, Yuan Z. Effects of sodium hydroxide, sodium hypochlorite, and gaseous hydrogen peroxide on the natural properties of cancellous bone. Artificial Organs. 2013 doi: 10.1111/aor.12048. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelka M, Petschelt A. Permanent mimic musculature and nerve damage caused by sodium hypochlorite: a case report. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2008;106:e80–e83. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeh ES, Messer HH. Long-term paresthesia following inadvertent forcing of sodium hypochlorite through perforation in maxillary incisor. Endodontics and Dental Traumatology. 1989;5:200–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1989.tb00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neaverth EJ, Swindle R. A serious complication following the inadvertent injection of sodium hypochlorite outside the root canal system. Compendium. 1990;11:474, 476, 478–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hülsmann M, Hahn W. Complications during root canal irrigation- literature review and case reports. International Dental Journal. 2000;33:186–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2000.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehdipour O, Kleier DJ, Averbach RE. Anatomy of sodium hypochlorite accidents. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 2007;28:544–546. 548, 550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleier DJ, Averbach RE, Mehdipour O. The sodium hypochlorite accident: experience of diplomates of the American Board of Endodontics. Journal of Endodontics. 2008;34:1346–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SH, Chung MP, Cheng JC, Chen CP, Shieh YS. Sodium hypochlorite accidentally extruded beyond the apical foramen. Journal of Medical Science. 2010;30:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker GL, Cohen S, Borer R. The sequelae of accidentally injecting sodium hypochlorite beyond the root apex. Report of a case. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 1974;38:633–638. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermann JW, Heicht RC. Complications in the therapeutic use of sodium hypochlorite. Journal of Endodontics. 1979;5:160. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(79)80039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gursoy UK, Bostanci V, Kosger HH. Palatal mucosa necrosis because of accidental sodium hypochlorite injection instead of anaesthetic solution. International Dental Journal. 2006;39:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehrich DG, Brian JD, Jr, Walker WA. Sodium hypochlorite accident: inadvertent injection into the maxillary sinus. Journal of Endodontics. 1993;19:180–182. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavanagh CP, Taylor J. Inadvertent injection of sodium hypochlorite to the maxillary sinus. British Dental Journal. 1998;185:336–337. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zairi A, Lambrianidis T. Accidental extrusion of sodium hypochlorite into the maxillary sinus. Quintessence International. 2008;39:745–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauman CH, Chandler NP, Tong DC. Endodontic implications of the maxillary sinus: a review. International Dental Journal. 2002;35:127–141. doi: 10.1046/j.0143-2885.2001.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan S, Niu LN, Eid AA, Looney SW, Didato A, Roberts S, et al. Periapical pressures developed by nonbinding irrigation needles at various irrigation delivery rates. Journal of Endodontics. 2013;39:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang LM, Lak B, Eijsvogels LM, Wesselink P, van der Sluis LW. Comparison of the cleaning efficacy of different final irrigation techniques. Journal of Endodontics. 2012;38:838–841. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sleiman P. Irrigation for the root canal and nothing but the root canal. Dental Tribune. 2013 http://www.dental-tribune.com/articles/specialities/endodontics/11609. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabala CL, Powell SE. Sodium hypochlorite injection into periapical tissues. Journal of Endodontics. 1989;15:490–492. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(89)80031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer HR, Ike V, Brennan PA. Review: the use of sodium hypochlorite in endodontics - potential complications and their management. British Dent Journal. 2007;202:555–559. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatot A, Arbelle J, Leiberman A, Yanai-Inbar I. Effects of sodium hypochlorite on soft tissues after its inadvertent injection beyond the root apex. Journal of Endodontics. 1991;17:73–74. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81725-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balto H, Al-NaZhan S. Accidental injection of sodium hypochlorite beyond the root apex. Saudi Dental Journal. 2002;14:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam TSM, Wong OF, Tang SYH. A case report of sodium hypochlorite accident. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;17:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tegginmani VS, Chawla VL, Kahate MM, Jain VS. Hypochlorite accident – A case report. Endodontology. 2011;23:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behrents KT, Speer ML, Noujeim M. Sodium hypochlorite accident with evaluation by cone beam computed tomography. International Endodontic Journal. 2012;45:492–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Sermeño RF, da Silva LA, Herrera H, Herrera H, Silva RA, Leonardo MR. Tissue damage after sodium hypochlorite extrusion during root canal treatment. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2009;108:e46–e49. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hülsmann M, Rödig T, Nordmeyer S. Complications during root canal irrigation. Endodontic Topics. 2009;16:27–63. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, Ghedini G, Papadia F. Severe facial edema following root canal treatment. Archives of Dermatology. 1996;132:231–233. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1996.03890260135024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehra P, Clancy C, Wu J. Formation of a facial hematoma during endodontic therapy. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2000;131:67–71. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldwin VE, Jarad FD, Balmer C, Mair LH. Inadvertent injection of sodium hypochlorite into the periradicular tissues during root canal treatment. Dental Update. 2009;36:14–16. 19. doi: 10.12968/denu.2009.36.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J, Lorenzo D, Rawlins T, Cardo VA., Jr Sodium hypochlorite extrusion: an atypical case of massive soft tissue necrosis. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;69:1776–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bosch-Aranda ML, Canalda-Sahli C, Figueiredo R, Gay-Escoda C. Complications following an accidental sodium hypochlorite extrusion A report of two cases. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 2012;4:e194–e198. doi: 10.4317/jced.50767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becking AG. Complications in the use of sodium hypochlorite during endodontic treatment. Report of three cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 1991;71:346–348. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chaudhry H, Wildan TM, Popat S, Anand R, Dhariwal D. Before you reach for the bleach. British Dental Journal. 2011;210:157–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Witton R, Brennan PA. Severe tissue damage and neurological deficit following extravasation of sodium hypochlorite solution during routine endodontic treatment. British Dental Journal. 2005;198:749–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witton R, Henthorn K, Ethunandan M, Harmer S, Brennan PA. Neurological complications following extrusion of sodium hypochlorite solution during root canal treatment. International Dental Journal. 2005;38:843–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bowden JR, Ethunandan M, Brennan PA. Life-threatening airway obstruction secondary to hypochlorite extrusion during root canal treatment. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2006;101:402–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gernhardt CR, Eppendorf K, Kozlowski A, Brandt M. Toxicity of concentrated sodium hypochlorite used as an endodontic irrigant. International Endodontic Journal. 2004;37:272–280. doi: 10.1111/j.0143-2885.2004.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paschoalino Mde A, Hanan AA, Marques AA, Garcia Lda F, Garrido AB, Sponchiado EC., Jr Injection of sodium hypochlorite beyond the apical foramen - a case report. General Dentistry. 2012;60:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oreadi D, Hendi J, Papageorge MB. A clinico-pathologic correlation. Journal of the Massachusetts Dental Society. 2010;59:44–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crincoli V, Scivetti M, Di Bisceglie MB, Pilolli GP, Favia G. Unusual case of adverse reaction in the use of sodium hypochlorite during endodontic treatment: a case report. Quintessence International. 2008;39:e70–e73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torabinejad M, Walton RE, editors. Endodontics: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. Chapter 18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joffe E. Complication during root canal therapy following accidental extrusion of sodium hypochlorite through the apical foramen. General Dentistry. 1991;39:460–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. pp. 273–274. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hollinshead WH. The head and neck. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Jagerstown: Harper & Row; 1982. Anatomy for surgeons; p. 467. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drake R, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 2nd Edition. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2009. Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schreid RC. Woelfel’s Dental Anatomy: Its relevance to Dentistry. 7th Edition. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Netter FH. Atlas of human Anatomy, Professional Edition. 5th Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu DC, Tam A, Schilder H. Patency and envelope of motion - two essential procedures for cleaning and shaping the root canal systems. General Dentistry. 2009;57:616–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Flanders DH. Endodontic patency. How to get it. How to keep it. Why it is so important. New York State Dental Journal. 2002;68:30–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vera J, Hernández EM, Romero M, Arias A, van der Sluis LW. Effect of maintaining apical patency on irrigant penetration into the apical two millimeters of large root canals: an in vivo study. Journal of Endodontics. 2012;38:1340–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Camoes IC, Salles MR, Fernando MV, Freitas LF, Gomes CC. Relationship between the size of patency file and apical extrusion of sodium hypochlorite. Indian Journal of Dental Research. 2009;20:426–430. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.59443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bergenholtz G, Spångberg L. Controversies in Endodontics. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2004;15:99–114. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang J, Stringer MD. Ophthalmic and facial veins are not valveless. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 2010;38:502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salzgeber RM, Brilliant JD. An in vivo evaluation of the penetration of an irrigating solution in root canals. Journal of Endodontics. 1977;3:394–398. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(77)80172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Kastrinakis E. Irrigant flow within a prepared root canal using various flow rates: a Computational Fluid Dynamics study. International Endodontic Journal. 2009;42:144–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boutsioukis C, Verhaagen B, Versluis M, Kastrinakis E, Wesselink PR, van der Sluis PR. Evaluation of irrigant flow in the root canal using different needle types by an unsteady computational fluid dynamics model. Journal of Endodontics. 2010;36:875–897. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Verhaagen B, Versluis M, Kastrinakis E, Wesselink PR, et al. The effect of needle-insertion depth on the irrigant flow in the root canal: evaluation using an unsteady computational fluid dynamics model. Journal of Endodontics. 2010;36:1664–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shen Y, Gao Y, Qian W, Ruse ND, Zhou X, Wu H, et al. Three-dimensional numeric simulation of root canal irrigant flow with different irrigation needles. Journal of Endodontics. 2010;36:884–889. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Izakovic M. Central venous pressure - evaluation, interpretation, monitoring, clinical implications. Bratislavské Lekárske Listy. 2008;109:185–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lyons RH, Kennedy JA, Burwell CS. Measurement of venous pressure by direct method. American Heart Journal. 1938;16:675–693. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baumann UA, Marquis C, Stoupis C, Willenberg TA, Takala J, Jakob SM. Estimation of central venous pressure by ultrasound. Resuscitation. 2005;64:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park E, Shen Y, Khakpour M, Haapasalo M. Apical pressure and extent of irrigant flow beyond the needle tip during positive-pressure irrigation in an in vitro root canal model. Journal of Endodontics. 2013;39:511–515. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boutsioukis C, Lambrianidis T, Kastrinakis E, Bekiaroglou P. Measurement of pressure and flow rates during irrigation of a root canal ex vivo with three endodontic needles. International Endodontic Journal. 2007;40:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peck B, Workeneh B, Kadikoy H, Patel SJ, Abdellatif A. Spectrum of sodium hypochlorite toxicity in man – also a concern for nephrologists. NDT Plus. 2011;0:1–5. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoy RH. Accidental systemic exposure to sodium hypochlorite (Chlorox) during hemodialysis. American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 1981;38:1512–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morgan DL. Intravenous injection of household bleach. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1992;21:1394–1395. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81909-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rahmani SH, Ahmadi S, Vahdati SS, Moghaddam HH. Venous thrombosis following intravenous injection of household bleach. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 2012;31:37–39. doi: 10.1177/0960327111432506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Verma A, Vanguri VK, Golla V, Rhyee S, Trainor M, Abramov K. Acute kidney injury due to intravenous bleach injection. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2013;9:71–74. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Muth CM, Shank ES. Gas embolism. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:476–482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002173420706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drinker CK, Drinker KR, Lund CC. The circulation in the mammalian bone marrow. American Journal of Physiology. 1922;62:1–92. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Draenert K, Draenert Y. The vascular system of bone marrow. Scanning Electron Microscopy. 1980;4:113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oni OO, Stafford H, Gregg PJ. An investigation of the routes of venous drainage from the bone marrow of the human tibial diaphysis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1988;230:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Saint-Georges L, Miller SC. The microcirculation of bone and marrow in the diaphysis of the rat hemopoietic long bones. The Anatomical Record. 1992;233:169–177. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092330202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kofoed H. Intraosseous pressure, gas tension and bone blood flow in normal and pathological situations: A survey of methods and results. In: Bone Circulation and Vascularization in Normal and Pathological Conditions. NATO ASI Series. 1993;247:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gurkan UA, Akkus O. The mechanical environment of bone marrow: a review. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2008;36:1978–1991. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shaw NE. Studies on intramedullary pressure and blood flow in bone. American Heart Journal. 1964;68:134–135. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(64)90250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shim SS, Hawk HE, Yu WY. The relationship between blood flow and marrow cavity pressure of bone. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1972;135:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tocantins LM. Rapid absorption of substances injected into the bone marrow. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1940;45:292–296. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tocantins LM, O'neill JF, Price AH. Infusion of blood and other fluids via the bone marrow in traumatic shock and other forms of peripheral circulatory failure. Annals of Surgery. 1941;114:1085–1092. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194112000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tocantins LM, O’Neill JP, Jones HW. Infusion of blood and other fluids via the bone marrow. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1941;117:1229–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pillar S. Re-emphasis on bone marrow as a medium for administration of fluid. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1954;251:846–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195411182512103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dubick MA, Holcomb JB. A review of intraosseous vascular access: current status and military application. Military Medicine. 2000;165:552–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reades R, Studnek JR, Vandeventer S, Garrett J. Intaosseous versus intravenous vascular access during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2011;58:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Olaussen A, Williams B. Intraosseous access in the prehospital setting: literature review. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2012;27:468–472. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12001124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Voigt J, Waltzman M, Lottenberg L. Intraosseous vascular access for in-hospital emergency use: a systematic clinical review of the literature and analysis. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2012;28:185–199. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182449edc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brown R. Intraosseous anesthesia: a review. Journal of the California Dental Association. 1999;27:785–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nusstein J, Wood M, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. Comparison of the degree of pulpal anesthesia achieved with the intraosseous injection and infiltration injection using 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. General Dentistry. 2005;53:50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bangerter C, Mines P, Sweet M. The use of intraosseous anesthesia among endodontists: results of a questionnaire. Journal of Endodontics. 2009;35:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Papper EM. The bone marrow route for injecting fluids and drugs into the general circulation. Anesthesiology. 1942;3:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rickles NH, Joshi BA. A possible case in a human and an investigation in dogs of death from air embolism during root canal therapy. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1963;67:397–404. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1963.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Davies JM, Campbell LA. Fatal air embolism during dental implant surgery: a report of three cases. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 1990;37:112–121. doi: 10.1007/BF03007491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Goode N, Khan S, Eid AA, Niu LN, Gosier J, Susin LF, et al. Wall shear stress effects of different endodontic irrigation techniques and systems. Journal of Dentistry. 2013;41:636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]