Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports estimate that 85% of newborn deaths are due to infections, prematurity and fetal distress. These conditions are risk factors for upper GI bleeding (UGIB) in sick neonates. UGIB is associated with poor neonatal outcomes such as prolonged hospitalisation and poor weight gain. The magnitude of UGIB and its contribution to neonatal morbidity has not been described in most low income countries.

Objective

To determine the occurrence and factors associated with UGIB among neonates admitted to the Special Care Unit (SCU) of Mulago Hospital.

Methods

This was a prospective single cohort study where neonates admitted within 24 hours of birth were consecutively enrolled and followed up for seven days. Gastric aspirates from the neonates were examined daily over a period of 7 days using Guaiac and Apt tests for evidence of UGIB. Data on occurrence of UGIB has been presented as proportions and Odds Ratios for associated factors.

Results

Out of 191 neonates, 44 (23 %) developed UGIB. Factors independently associated with UGIB included cyanosis in the neonate [OR 5.8; (95% CI; 1.8 – 19.1) p-value 0.004], neonatal seizures [OR 12.6; (95% CI 2.3 – 70.5); p-value 0.004] and birth asphyxia [OR 6.3; (95% CI 1.9 – 21.6); p-value 0.003].

Conclusions

In the first seven days of life, UGIB occurred in 1:4 neonates. Factors independently associated with UGIB included birth asphyxia, cyanosis in the neonate and neonatal seizures.

Keywords: Upper GI bleeding, Neonates, Uganda

Introduction

Upper GI bleeding in neonates occurs in 10 to 40% of critically ill neonates, especially among those suffering from infections, preterm birth, thrombocytopenia and birth asphyxia 1–4. This condition is associated with poor neonatal outcomes such as prolonged hospitalization and poor weight gain. Most of the published studies have been conducted in high income countries with better neonatal care and outcomes compared to the low income countries. The magnitude of UGIB bleeding and its contribution to neonatal morbidity have not been described in most low income countries. In this paper we describe the occurrence of UGIB in a neonatal unit at Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda and associated factors.

Methods

Study design and Setting

This was a prospective cohort study, conducted in November and December 2010 at the Special Care Unit (SCU) of Mulago Hospital. Mulago Hospital is a national referral hospital for Uganda and the Teaching Hospital for Makerere University. The SCU, which serves as the neonatal intensive care unit, receives ill or preterm neonates of age less than 24 hours born in or referred to Mulago Hospital.

Sample size estimation

A sample size for occurrence of UGIB of 141 was based on a 10.2% prevalence of UGIB 3 using Keish Leslie formula. Based on a reported association between thrombocytopenia and UGIB5, a sample size 173 for factors associated with UGIB was obtained using the Fleiss formula6. Adding 10% loss to follow up to the larger sample size of 173, a sample size of 191 was required for the study.

Enrolment of patients

All neonates admitted to the SCU during the study period were eligible for participation. Those whose mother/caretaker provided informed consent were enrolled. Babies born before arrival to hospital, those who already had UGIB at admission and neonates older than 24 hours at enrollment were excluded. Neonates were recruited every day between 8:00 am and 8:00pm, while those admitted after 8.00pm were recruited the following morning. All the participants had a detailed physical examination including gestation age assessment using the New Ballard's scoring system.

Specimen collection and lab analysis

All the neonates had an NG tube gauge 5 inserted. At least 2 ml of gastric aspirates were collected once daily between 8–9.00 am and sent for occult blood analysis at the Clinical chemistry laboratory. Part of the sample from aspirates that tested positive for occult blood was subjected to an Apt test to determine the origin of the blood. Peripheral blood samples were taken for a complete blood count at the hematology laboratory of Mulago hospital.

Follow up

All the neonates in this study were followed up for seven days, or until they developed UGIB, or death or discharge or the attending doctors recommend removal of the NG tube, whichever came first.

Data Management

Data was collected using a structured questionnaire, entered into a database using EPI DATA 3.1 and analyzed using STATA version 10. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant using confidence intervals of 95%. Laboratory, maternal and infant characteristics were compared among infants who had UGIB versus those who did not have UGIB. Factors with a p-value of less than 0.1 were entered into logistic regression by backward stepwise method and tested for confounding and interaction to the independent variable.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all the mothers of the participating neonates. Approval to carry out this study was obtained from the Institutional Research and Ethics committee of Makerere University Medical School, Mulago Hospital Ethics Committee and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Results

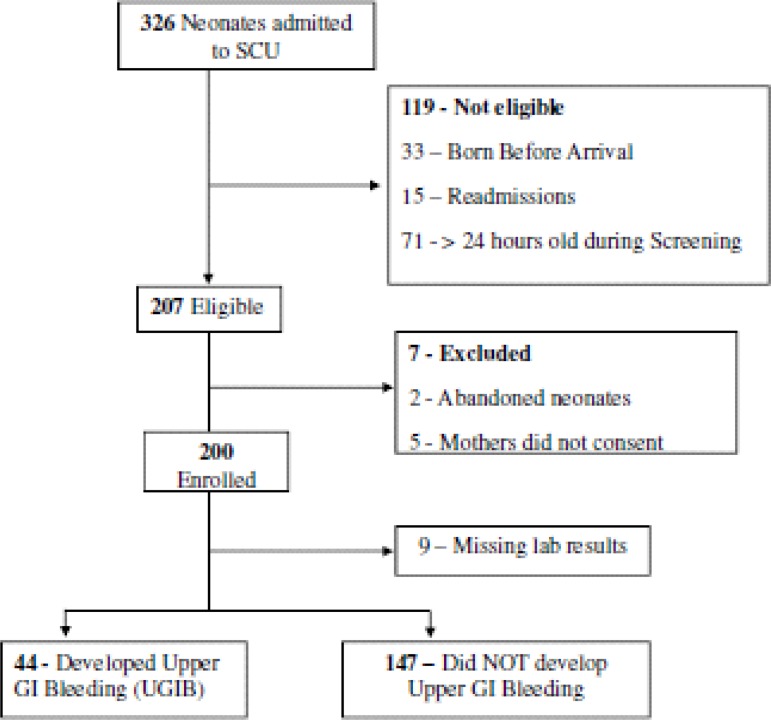

During the months of November and December 2010, three hundred and twenty six (326) neonates admitted to the SCU were screened, out of which 207 were eligible. As shown in figure 1, seven eligible neonates were excluded because 5 mothers refused to consent and 2 babies were abandoned and had no caretakers. A further 9 neonates were excluded from the analysis because of missing laboratory results. All the study subjects were less than 24 hours old at enrollment. The mean gestational age of the study participants was 35.0 weeks (SD 3.0) and the mean birth weight was 2.4 kg (SD 0.8). The other characteristics are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Study Profile

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 191 neonates assessed for occurrence of UGIB

| Variable | Frequency(191) | Percentage(%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 103 | 54.0 |

| Female | 88 | 46.0 |

| Birth type | ||

| Single | 142 | 74.4 |

| Twin | 49 | 25.6 |

| Duration of Labor | ||

| Normal(< 18 Hours) | 100 | 52.4 |

| Prolonged(> 18 Hours) | 91 | 47.6 |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Vaginal | 136 | 71.2 |

| Cesarean section | 55 | 28.8 |

| HIV exposure | ||

| Not exposed | 142 | 74.3 |

| Exposed | 33 | 17.3 |

| Unknown | 16 | 8.4 |

| Gestation Age | ||

| Preterm( < 37wks) | 102 | 53.4 |

| Term( > 37wks) | 89 | 46.6 |

| Birth Weight | ||

| Low < 2.5Kg | 109 | 57.1 |

| Normal > 2.5Kg | 82 | 42.9 |

| Axillary temperature (°C) | ||

| Low < 35.5 | ||

| Normal 35.5 – 37.5 | ||

| High > 37.5 | 7010912 | 36.757.06.3 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | ||

| Low < 40 | 21 | 0.16 |

| Normal 40 – 59 | 25 | 5.4 |

| High > 60 | 64 | 34.5 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | ||

| Low < 100 | 4 | 2.1 |

| Normal 100 – 160 | 175 | 91.6 |

| High > 160 | 12 | 6.3 |

| Apgar Score at 5 min | ||

| Low < 7 | 84 | 44.0 |

| Normal >7 | 107 | 56.0 |

Laboratory findings of study subjects

Of the 191 participants, 23 had a low platelet count of < 150,000/µL. As shown in table 2, a total of 92 neonates had a positive guaiac test in their gastric aspirates. Out of these 92 neonates, 44 had a negative Apt test, indicating that the blood in the aspirates was of neonatal origin; while 48 samples with positive Apt test contained swallowed maternal blood.

Table 2.

Laboratory findings of neonates assessed for occurrence of UGIB

| Variable | Frequency(191) | Percentage(%) |

| WBC count | ||

| Low (<9,000/µL) | 40 | 20.9 |

| Normal (9,000 – 30,000/µL) | 138 | 72.3 |

| High (> 30,000/µL) | 13 | 6.8 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dl) | ||

| Low (< 15g/dl) | 33 | 17.3 |

| Normal (> 15g/dl) | 158 | 82.7 |

| Platelet count | ||

| Thrombocytopenia (<150,000) | 23 | 12.0 |

| Normal > 150,000 | 168 | 88.0 |

| Occult blood in gastric aspirates (Guaiac test) | ||

| Positive | 92 | 48.2 |

| Negative | 99 | 51.8 |

| Apt Test on occult blood positive gastric aspirates | ||

| Positive for swallowed blood | 48 | 52.2 |

| Negative | 44 | 47.8 |

Occurrence of UGIB

In this study, 23.0% of the neonates followed up developed UGIB. A majority (59.0%) of those 44 neonates were male and 59.1% were term babies.

Factors associated with UGIB

Table 3 shows the diagnosis, clinical and laboratory findings associated with UGIB on bivariate analysis. As shown in table 4, factors independently associated with UGIB include cyanosis in the neonate, neonatal seizures and birth asphyxia.

Table 3.

Diagnosis, Clinical and Laboratory findings associated with UGIB

| Variable | Developed UGIB | NO UGIB | OR(95% CI) | P value |

| N = 44(%) | N= 147(%) | |||

| Thrombocytopenia (<150,000) | 10 (22.7) | 13(8.8) | 3.0(1.2 -7.6) | 0.013 |

| Hemoglobin level (<15g/dl) | (18.2) | 25(17.0) | 1.1(0.5 – 2.6) | 0.857 |

| Neonatal seizures | 8 (18.2) | 2(1.4) | 15.9(3.0 – 85.5) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Distress Syndrome | 1 (2.3) | 4(2.7) | 1.2(0.1 – 11.1) | 0.871 |

| Birth asphyxia | 26 (59.1) | 42(28.6) | 4.1(2.0 – 8.6) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal jaundice | 6 (13.6) | 16(10.9) | 1.3(0.5 – 3.5) | 0.617 |

| Neonatal septicemia | 2 (4.6) | 11(7.5) | 1.7(0.4 – 8.0) | 0.498 |

| Small for gestation age | 3 (6.8) | 17(11.6) | 1.8(0.5 – 6.4) | 0.368 |

| Mothers age < 20 years | 11(25.0) | 26(17.7) | 1.6(0.7 – 3.5) | 0.282 |

| Vaginal Discharge | 21(47.7) | 45(30.6) | 2.1(1.0 – 4.2) | 0.037 |

| Malaria in Pregnancy | 8 (18.2) | 17(11.6) | 1.7(0.7 – 4.3) | 0.252 |

| HIV exposure of the neonate | 8 (18.2) | 25(17.0) | 1.1(0.4 – 2.6) | 0.857 |

| Prolonged labor (>18 hours) | 27 (61.4) | 74(50.3) | 2.1(1.0 – 4.1) | 0.038 |

| Low Apgar Score at 5 min | 28 (63.6) | 56(38.1) | 2.9(1.4 – 5.8) | 0.003 |

| Baby resuscitated by bag and mask | 27 (61.4) | 50(34.0) | 3.1(1.5 – 6.3) | 0.001 |

| after birth | ||||

| Preterm delivery(<37 weeks) | 18 (40.9) | 84(57.1) | 1.9(1.0 – 3.8) | 0.059 |

| Hypothermia (< 35.5oC) | 19 (43.2) | 51(34.7) | 1.4(0.7 – 2.8) | 0.311 |

| Cyanosis in neonate | 8 (18.2) | 10(6.8) | 5.1(1.8 – 14.4) | 0.001 |

| Birth weight > 2500gm | 26 (59.1) | 56(38.1) | 2.3(1.2 – 4.7) | 0.014 |

| Respiratory rate (>60b/min) | 15 (34.1) | 49(33.3) | 1.0(0.5 – 2.0) | 0.926 |

Note:

92% of the babies with birth asphyxia were term deliveries.

Of the 23 study subjects with thrombocytopenia; only 10 developed UGIB. Of these 10 subjects, 6 had mild thrombocytopenia (100,000 – 150,000), 3 had moderate thrombocytopenia (50,000 – 100,000) and only 1 had severe thrombocytopenia (<50,000).

Table 4.

Factors independently associated with UGIB

| Variable | Developed | COR* | P value | AOR*(95% CI) | P value |

| UGIB | (95% CI) | ||||

| N= 44 (%) | |||||

| Preterm delivery | 18 (40.9) | 2.0(1.0 – 3.9) | 0.059 | 3.3(1.0 – 11.5) | 0.059 |

| (<37 weeks) | |||||

| Cyanosis in neonate | 8 (18.2) | 5.1(1.8 – 14.4) | 0.001 | 5.8(1.8 – 19.1) | 0.004 |

| Neonatal seizures | 8 (18.2) | 15.9(3.0 – 85.5) | <0.001 | 12.6(2.3 – 70.5) | |

| 0.004 | |||||

| Birth asphyxia | 26 (59.1) | 4.1(2.0 – 8.6) | <0.001 | 6.3(1.9 – 21.6) | 0.003 |

Discussion

In this study, almost a quarter of the neonates developed UGIB, a figure that lies within the range of 5.5% – 43.5% found by various studies3, 7–10. The prevalence in this study is less than what some studies reported most probably because the neonates in this study had advanced gestation age and were less likely to be on mechanical ventilation and other invasive procedures. A higher figure of 43.5% 2 was reported among children diagnosed with stress ulceration, while Deerojanawong et al reported 51.8% in among children on mechanical ventilation, a recognized risk factor for UGIB5.

A closer proportion of 20% was reported by Kuusela et al 9 while Cochran et al, found 25% of the 208 patients followed up developed UGIB11. Proportions as low as 6% have been reported in some studies12, 13 which considered a general pediatric population. While ranitidine prophylaxis decreases the incidence of UGIB in critically ill children9, 14, 15, it is not known whether the prevalence in this study would have been lower than 23.0% had the study subjects received ranitidine prophylaxis against UGIB. As previously reported 3, 9, 16, this study has supported the association between birth asphyxia and UGIB. UGIB in neonates with birth asphyxia has been attributed to stress of illness, which is a known risk for gastric ulceration occurring in up to 20% of patients cared for in the neonatal ICU9. Stress increases gastric acid secretion and plays a key role in ulceration in older children and adults17. In this study, most of the neonates who suffered from asphyxia were born after prolonged labor, had a low Apgar score and required resuscitation by bag and mask immediately after birth. Birth asphyxia, cyanosis in the neonate and neonatal seizures were independently associated with UGIB and no interaction between birth asphyxia, seizures and cyanosis was found during analysis. Most babies in this study developed UGIB on the 2nd and 3rd day of follow up.

All the neonates in this study received routine vitamin K injection on admission, a factor that could have reduced the risk of bleeding due to deficiency of vitamin K dependent clotting factors. In this study, thrombocytopenia was found to occur among 12%, of the neonates, a figure that is much lower than the reported range of 18–35 %18–20. Similar to previous studies1, 9, this study found that thrombocytopenia was significantly associated with UGIB. However, reasonable conclusions at different degrees of thrombocytopenia could not be made, since the number for the different levels of thrombocytopenia were few. Christensen et al attributed thrombocytopenia in neonates (especially ELBW) to the effect of early onset infection, thrombi, DIC, and severe hemorrhages19. This study however did not establish an association between septicemia and UGIB or between septicemia and thrombocytopenia. In this study, all subjects received routine prophylactic antibiotics, an intervention that could have reduced the prevalence of septicemia and thrombocytopenia. While studies show that maternal medication (aspirin, heparin, indomethacin) increase the risk of UGIB in the neonates16, 21, this study did not find any such association, partly because of the small numbers since only 2 mothers were on heparin, 2 aspirin and none on warfarin.

Conclusion

In the first seven days of life, UGIB occurred in 1 in 4 neonates admitted to SCU of Mulago Hospital. Factors independently associated with UGIB include birth asphyxia, cyanosis in the neonate and neonatal seizures.

Acknowledgement

We thank Save the Children Uganda for the financial support for this work. Many thanks go to the research assistants Damalie, Liz and Immaculate, the laboratory technicians Hosea and Wilson, and statistician Deo and Leonard and all staff of the SCU for their hard work and co-operation that made this study successful. Lastly, we are grateful to all neonates and their parents/caregivers for accepting to participate in this study.

This work was part of a thesis submitted by Dr. Ombeva in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Makerere University Masters of Medicine (M.Med) in Paediatrics and Child Health.

References

- 1.Arora NK, Ganguly S, Mathur P, Ahuja A, Patwari A. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: etiology and management. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:155–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02859378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nithiwathanapong Chookhuan, Sanit Reungrongrat, Nuthapong Ukarapol. Prevalence and risk factors of stress-induced gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill children. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6839–6842. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i43.6839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaïbou Mahamadou, Tucci Marisa, Dugas Marc-André, Farrell Catherine Ann, Proulx François, Lacroix J. Clinically Significant Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Acquired in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Prospective Study. Pediatrics. 1998;102:933–938. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neonatal and perinatal mortality, Country, regional and global estimates. WHO Press; 2006. [2nd August, 2010]. at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241563206_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jitladda Deerojanawong, Danayawan Peongsujarit, Boosba Vivatvakin, Nuanchan Prapphal. Incidence and risk factors of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in mechanically ventilated children. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2009;10:91–95. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181936a37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Formula for Calculating Sample size for difference in proportions. 2010. Jul, (Accessed at http://www.openepi.com/OE2.3/Menu/OpenEpiMenu.htm.)

- 7.Cook DJ, Fuller HD, Guyatt GH, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:377–381. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fusamoto H, Hagiwara H, Meren H, et al. A clinical study of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with various shock states. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuusela AL, Maki M, Ruuska T, Laippala P. Stress-induced gastric findings in critically ill newborn infants: frequency and risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1501–1506. doi: 10.1007/s001340051346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pimentel M, Roberts DE, Bernstein CN, Hoppensack M, DR D. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients in an era of prophylaxis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2801–2806. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochran EB, Phelps SJ, Tolley EA, Stidham GL. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in critically ill pediatric patients. Crit Care Med. 1992 Nov;20:1519–1523. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacroix J, Nadeaus D, Laberge S. Frequency of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1992;8:35–42. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liebman M, Thaler MM, Buvanover Y. Endoscopic evaluation of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the newborn. Am J Gastroenterol. 1978;69:607–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludovic, Reveiz, Rafael, et al. Stress ulcer, gastritis, and gastrointestinal bleeding prophylaxis in critically ill pediatric patients: A systematic review. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2010 Jan 11;:124–132. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b80e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pourarian S, Imani B, Imanieh MH. Prophylactic Ranitidine in Prevention of GI Bleeding in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Iran J Med Sci. 2005;30:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzaroni M, Petrillo M, Tornaghi R, et al. Upper GI Bleeeding in Healthy Full-Term Infants: A case - Control Study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maki M, Russka T, Kussela AL. High prevalence of asymptomatic esopHageal and gastric lesions in preterm infants in intensive care. Crit care Med. 1993;21:1863–1868. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199312000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lea Bonifacio, Anna Petrova, Shakuntala Nanjundaswamy, Rajeev Mehta. Thrombocytopenia Related neonatal outcomes in Preterms. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:269–274. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen RD, Henry E, Wiedmeier SE, et al. Thrombocytopenia among extremely low birth weight neonates: data from a multihospital healthcare system. Journal of Perinatology. 2006;26:348–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts I, Murray NA. Review; Neonatal thrombocytopenia: causes and management. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F359–F364. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.5.F359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-Herce J, Dorao P, Elola P, Delgado MA, Ruza F, Madero R. Frequency and prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in critically ill children: a prospective study comparing the efficacy of almagate, ranitidine and sucralfate. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1082–1089. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]