Abstract

Background

Febrile neutropenia (FN) is generally a complication of cancer chemotherapy.

Objectives

We retrospectively evaluated the febrile neutropenia episodes and their outcomes with respect to modification rates of non-carbapenem-based empirical antibacterial therapy and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) colonisation that caused to VRE bacteremia in patients with hematological malignancies.

Methods

All consecutive patients, who were older than 14 years of age and developed febrile neutropenia episodes due to hematological malignancies from September 2010 to November 2011 at the hematology department were included into the study.

Results

In total, 86 consecutive neutropenic patients and their 151 febrile episodes were evaluated. The mean MASCC prognostic index score was 18,72 ± 9,43. Among 86 patients, 28 patients experienced a total of 30 bacteremia episodes of bacterial origin. Modification rates of both, empirical monotherapy and combination therapies, were found similar, statistically (P = 0,840).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that initiating of non-carbapenem based therapy does not provide high response rates in the treatment of febrile neutropenia attacks. Furthermore, non-carbapenem-based empirical therapy provides benefit in regard to cost-effectiveness and antimicrobial stewardship when local antibiotic resistance patterns of gram-negative bacteria are considered. Patients who are colonized with VRE are more likely to develop bacteremia with VRE strains as a result of invasive procedures and severe damage of mucosal barriers observed in this group of patients.

Keywords: Hematological malignancy, febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, VRE, colonisation, ESBL, gram-negative bacteria

Introduction

Febrile neutropenia (FN) is generally a complication of cancer chemotherapy1, 2. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) prognostic index indicates that mortality is as low as 3% if the MASCC score is >21, but as high as 36% if the MASCC score is <153. Patients with bacteremia are more likely to have a poor prognosis with mortality rates of 18% with gram-negative bacteremia and 5% with gram-positive bacteremia. Among grampositive bacteria, bacteremia due to coagulasenegative staphylococci has been shown to cause to low mortality, enterococci to moderate mortality, and Staphylococcus aureus to high mortality4. Mortality related with FN has been steadily decreasing with the implementation of guidelines, new laboratory tests and serial computed tomography (CT) scanning, with overall mortality rates ranging from as low as 5% in patients with solid tumors (1% in low-risk patients) to as high as 11% in some hematological malignancies5. Empirical antibacterial therapy should contain an anti-pseudomonal antimicrobial agent which must be chosen according to cumulative local antimicrobial resistance data. Although carbapenems are recommended as empirical antibiotic therapy options in febrile patients with neutropenia, they should be used with care due to the increasing rates of carbapenem resistant gram-negative bacteria worldwide1. Hence, non-carbapenem antipseudomonal antimicrobials are recommended in instances where the local antimicrobial resistance for carbapenems rates are low 1.

Enterococci are found in the gastrointestinal tract flora, oropharyngeal secretions, and on the skin 5. They may cause nosocomial infections in vulnerable patients who are colonized with vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE) or exposure to contaminated tools or hands of medical staff6

Advanced age, severity of illness, inter-institutional transfer of the patient, prolonged hospital stay, gastrointestinal surgery, transplantation, exposure to medical devices, especially central venous catheters, and heavy exposure to broad-spectrum antimicrobial drugs were reported as risk factors for colonization and infection with VRE7. Here, we retrospectively evaluated the FN episodes and their outcomes with respect to modification rates of non-carbapenem-based empirical antibacterial therapy and VRE colonisation that proceeded to VRE bacteremia in patients with hematological malignancies.

Methods

All consecutive patients between September 2010 and November 2011, who were older than 14 years of age and developed FN episodes during chemotherapy due to hematological malignancies at the hematology department of Okmeydaný Training and Research Hospital were enrolled in this retrospective and observational study. The hematology department was equipped with 23 beds. The patient rooms were designed as single, double and four-person without high-efficiency particulate air filters. FN was defined as an oral temperature of >38.5°C or two consecutive readings of >38.0°C for 2 h and an absolute neutrophil count <0.5 × 109/L, or expected count to fall below 0.5 × 109/L1.

Collected data included patient demographics and diagnosis, episode data, clinical presentation and laboratory findings, clinical therapy, microbiological data and the outcome. The treatment protocol for FN of our hospital was based on clinical practice guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer, from 2002 and the update in 2010 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) guidelines1, 8, 9.

Therapeutic regimens that were active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa were chosen randomly in accordance with local antibiotic resistance status. They included piperacillin-tazobactam (PIP-TAZ) that was administered in a dose of 4.5 g q8h by infusion, cefoperazone-sulbactam (CEP-SUL) that was administered in a dose of 2 g q8h by infusion, or PIP-TAZ that was administered in a dose of 4.5 g q8h by infusion in combination with ciprofloxacin (CIP) that was administered in a dose of 400 mg q12h. Ciprofloxacin was combined in patients whose symptoms involving respiratory system predominated. Antibacterial treatment was changed to one of the carbapenem options; imipenem (administered in a dose of 500 mg q6h) or meropenem (administered in a dose of 1 gr q8h), or other effective antibiotics against pathogens grown in the sample culture, if they exhibited a persistent fever after two days of empirical antibiotic therapy or had clinical, laboratory and radiological findings.

Patients who received carbapenem empirically (imipenem administered in a dose of 500 mg q6h or meropenem administered in a dose of 1 gr q8h) in combination with other antimicrobials at admission or during FN attacks due to severity of illness or history of infections caused by resistant bacteria were recorded as well. Vancomycin was considered for specific clinical indications, including suspected catheter-related infection, skin or soft-tissue infection, pneumonia, or hemodynamic instability.

Patients who received one of the non-carbapenem, anti-pseudomonal antibiotic in combination with other antibiotics, were excluded from the evaluation of response to non-carbapenem-based therapy. Response to carbapenem-based therapy was evaluated in patients who received only one of the carbapenem options without any combined antimicrobials. Fungal pathogens and antifungal therapy were not evaluated in this study. Antibiotic doses were adjusted in the cases of hepatic or renal failure.

Blood samples drawn from vein or catheter were inoculated into BactAlert 3D bottles (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France). In addition, samples such as urine, sputum, wound, conjunctive, abscess, and catheter were inoculated onto 5% sheep-blood agar (Salubris Inc., Istanbul, Turkey), chocolate agar (Salubris Inc., Istanbul, Turkey) and MacConkey agar (Salubris Inc., Istanbul, Turkey). Susceptibility testing was performed using an automated broth microdilution method (Vitek 2, bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) and confirmations were made by the E test method (AB BIODISK, Solna, Sweden). The breakpoints defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2008) were used. VRE colonisation was screened by rectal swabs that were inoculated onto a bile-esculin-azide agar plate containing 6 µg/mL of vancomycin (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA). Plates were then incubated aerobically in 5 to 10% CO2 at 35 to 37°C for up to 48 hours (for confirmation of a negative result). Samples from patients were collected in two-week intervals. Colonisation with VRE was defined as positive culture of rectal swab until two rectal swab cultures which were taken with an interval of two weeks were negative without clinical and radiologic findings associated with VRE. The strains isolated from cultures, which were defined as colonisation or contamination by infectious diseases specialists or medical microbiologists, were excluded from the study.

Response to empirical therapy was defined as defervescence in 48–72 hours subsequent to initiation of antibiotic, recovery of increased levels of C reactive protein (CRP), leukocytosis or leukopenia, recovery of vital signs and clinical symptoms associated with infection (improvement in arterial blood-gas values, radiological improvement, negative urine culture for urinary system infection and recovery of signs and symptoms related to other infections). Treatment response rates of empirical antibacterial therapy without modification and VRE infection rates of patients colonized with VRE during the neutropenic phase were the primary outcomes of this study. Mortality rates, however, were the secondary outcomes of this study.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as mean±standard deviation and range. Percentile values were described without decimals. Overall mortality associated with FN was defined as death within 30 days after development of neutropenia. Mortality rates were calculated as proportion of patients who died during the neutropenic phase and due to infection to all patients who were included in the study. Modification rates were compared by Pearson chi-square. P value was set at < 0,05 for significance. Response to non-carbapenem-based therapy was calculated with proportion of patients who responded to non-carbapenem-based therapy to all patients who received a solo non-carbapenem, antipseudomonal antibiotic therapy. Response to solo carbapenem-based therapy was calculated with proportion of patients who responded to solo carbapenem-based therapy to all patients who received solo carbapenem only.

Results

We retrospectively analyzed 86 consecutive patients with neutropenia and their 151 febrile episodes. Of the 86 patients, 45 were male and the mean age was 47,65±15,06 years (range: 17–82 years). Mean MASCC score was 18,72 ± 9,43. The distribution of patients' hematological malignancies is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of hematologic malignancies in the patients with febrile neutropenia (n: 86)

| Hematologic malignancies | n (%) |

| Acute myeloblastic leukemia | 50 (58) |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 19 (22) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 5 (6) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 (4) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 2 (3) |

| Mantle-cell lymphoma | 2 (3) |

| Aplastic anemia | 1 (1) |

| Hairy cell leukemia | 1 (1) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with Burkitt's lymphoma |

1 (1) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1 (1) |

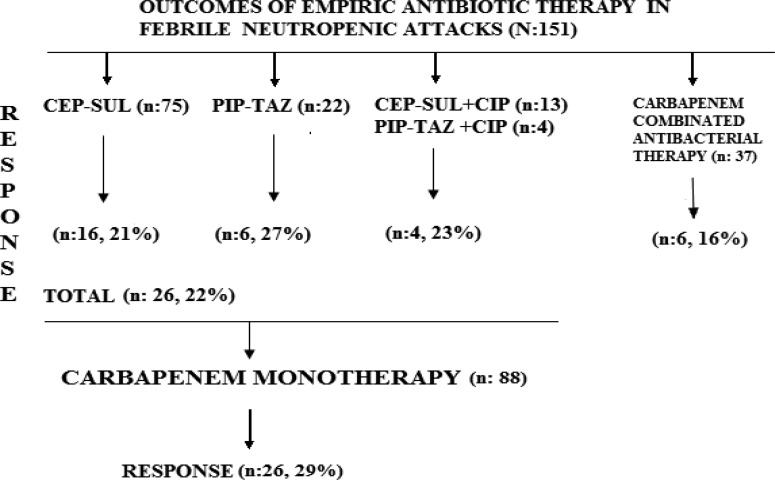

Bacteremia due to gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria was developed in 30 attacks in 28 patients (table 2). Empirical therapy with CEP-SUL was modified to carbapenem monotherapy in 59 of 75 (79%) febrile attacks. Empirical therapy with PIP-TAZ was modified to carbapenem monotherapy in 16 of 22 (73%) febrile attacks. Empirical therapies with CEP-SUL (n:13) or PIP-TAZ (n: 4) in combination with CIP were changed to carbapenem monotherapy in 13 of 17 (77%) febrile attacks. After switching to carbapenem monotherapy, 26 of 88 (29%) patients responded to therapy (figure 1).

Table 2.

Isolated bacteria that led to bacteremia in the patients with febrile neutropenia

| Hematologic Malignancy | n (%) |

| ESBL (+) E. coli | 1 (3,3) |

| ESBL (“) E. coli | 8 (26,7) |

| ESBL (+) K. pneumoniae | 3 (10,0) |

| ESBL (“) K. pneumoniae | 3 (10,0) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3 (10,0) |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (3,3) |

| Serratia ficaria | 1 (3,3) |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1 (3,3) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 (3,3) |

| Ochrobactrum anthropi | 1 (3,3) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1 (3,3) |

| MRSA | 3 (10,0) |

| MSSA | 1 (3,3) |

| Vancomycin sensitive Enterococcus faecium | 2 (6,7) |

| Total | 30 (100) |

ESBL; Extended spectrum beta-lactamase, MRSA; Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MSSA; Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus

Figure 1.

Response rates to non-carbapenem-based therapies and to carbapenem monotherapies in febrile neutropenia attacks (n: 151) CEP-SUL: Cefoperazone-sulbactam, PIP-TAZ: Piperacillin-tazobactam, CIP: Ciprofloxacin

Among patients who received carbapenem in combination with other antibacterials (n = 37), at admission or during FN attacks, without accompanying antifungal therapy, six of them (16%) responded to therapy (figure. 1). Other attacks were overcome with antifungal therapy. Modification rates of both, empirical monotherapy and combination therapy, were found similar, statistically (p= 0,840). In total, 30 bacteremia attacks by gram-negative (n = 24) and gram-positive bacteria (n = 6) developed and one of six patients with extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing gram-negative bacteria related bacteremia responded to CEP-SUL treatment without changing to carbapenems (table 2).

Non-carbapenem-based therapy achieved clinical and microbiological responses in six of 24 patients with gram-negative bacteremia. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia which was isolated from three sputum samples and was in concordance with radiological and clinical findings was successfully treated with imipenem. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was also isolated from catheter (n = 4), blood (n = 3) and sputum (n = 1) cultures belonged to five patients. MRSA related pneumonia did not respond to vancomycin therapy in a patient who subsequently died. Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was also isolated from abscess (n = 2), wound (n = 2) and blood (n = 1) cultures and CEP-SUL that was initiated empirically for FN provided good response. Vancomycin sensitive Enterococcus faecium was also isolated from wound (n = 1), urine (n = 1) and sputum (n = 1) cultures. VRE were isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage and blood cultures in one patient with pneumonia and dyspnea who was admitted from another hospital. All rectal swab cultures of this patient yielded normal flora bacteria during follow-up and the patient was successfully treated with linezolid. No VRE bacteremia developed during the 748 days of colonization in 65 patients. Only two patients who had persistent fever accompanied with diverse clinical findings (cough, pain in the anal region, ulcerations in oral mucosa, etc.) responded to linezolid treatment. Chemotherapy port catheter line and bone marrow biopsy were performed to patients colonised with VRE as invasive procedures during follow-up.

Overall mortality rates were 26% (n = 23) and 17 patients died due to infections including pneumonia, invasive fungal infections, urinary tract infections, central line blood stream infections and intraabdominal infections. MRSA bloodstream infections (n = 2), candidemia (n = 5) and vancomycin sensitive Enterococcus faecium that induced severe sepsis (n = 1) were recorded in patients who died.

Discussion

Non-carbapenem-based empirical antimicrobial monotherapy provided achievement comparable to that of non-carbapenem-based empirical combination therapy and also both frequently necessitated the shift to carbapenem-based therapy in febrile patients with neutropenia due to cancer chemotherapy. Previous randomized control trials and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed that monotherapy is not inferior to combination therapy in empirical treatment of febrile neutropenia10, 11. However, beta-lactam antibiotics that were initiated empirically were switched to one of the carbapenems after two days of treatment due to persistent clinical, radiological and laboratory findings according to IDSA and EORTC/MSG guidelines. Modification rates were lower with CEP-SUL (79%) compared to PIP-TAZ (73%) in our study. Moreover, CEP-SUL combined with CIP (23%) was found not superior compared to other monotherapy options (figure.1).

Carbapenems and other anti-pseudomonal antibiotics cured half of patients with FN attacks in monotherapy regimens. However, in one third of the patients with FN, low treatment response was obtained with a carbapenem combinated with another antimicrobial. Our results suggest that initiating of carbapenem based therapy does not provide high response rates in the treatment of febrile neutropenic attacks. Furthermore, non-carbapenem-based empirical therapy provides benefit in regard to cost-effectiveness and antimicrobial stewardship when local antibiotic resistance patterns of gram-negative bacteria are considered. Patients who are colonized with VRE are more likely to develop bacteremia with VRE strains as a result of invasive procedures and severe damage of mucosal barriers observed in this group of patients. Endogenous flora which is predominated by gram-negative bacteria, especially Enterobacteriaceae species in the gastrointestinal tract, can lead to fever in patients with neutropenia due to breakdown of mucosal barriers secondary to chemotherapy12.

Enterobacteriaceae species were predominant over other gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria in our study and non-ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae were noted as the most common isolates that caused to bacteremia. Infections with resistant gram-negative bacteria, especially with Enterobacteriaceae species, are a big challenge worldwide13. Switching from non-carbapenembased therapy to carbapenem-based therapy was mostly required due to increased resistance rates of gram-negative bacteria. In a previous study, Gedik et al. observed that fecal harboring of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates had reached a considerable frequency in the healthy population; 5% in Escherichia coli, 14% in Klebsiella pneumoniae and 20% in Klebsiella oxytoca isolates14. Although overall mortality rates for patients who received carbapenems and for those who received non-carbapenem anti-pseudomonal antibiotics were found similar, fewer cases of clinical failure and lower modification rates for glycopeptide antibiotics were reported in the patients who received carbapenems10. There has yet to be a randomized controlled trial for the treatment of bacteremia with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae species comparing beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations against carbapenems. Nevertheless, restrospective studies revealed that treatment response rates of nosocomial bacteremia were lower with beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations compared to carbapenems 15–17. Furthermore, inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy was reported to be a significant predictor for mortality in the patients with hematological malignancies18. MRSA bacteremia developed in three patients and two of them died.

For MRSA related infections, measures like screening, decolonisation, isolation and contact precautions for patients with MRSA should be taken, as MRSA infections were reported to increase in patients with FN19, 20. Patients who are admitted from healthcare facilities or nursing homes that have high MRSA colonization or infection rates should be screeened for MRSA colonisation, however, screening for MRSA is not indicated for settings with low MRSA infection rates21, 22. Long-term catheters that are implemented to administer chemotherapy predispose patients to MRSA related bacteremia and catheter infections.

VRE colonization predisposes patients to VRE bacteremia and was reported to be a poor prognostic factor in patients with neutropenia23. Moreover, invasive devices, broad-spectrum antibiotic use (vancomycin, cephalosporins, antianaerobic agents) and severity of illness have been reported as independent risk factors for VRE infection24.

However, only mucositis or increasing mucositis were reported as independent risk factors for VRE-related blood stream infection23. Invasive procedures or devices and mucositis may lead to VRE bacteremia in patients who are colonised with VRE and receive high dose cancer chemotherapy. The small number of invasive procedures in 65 patients were probably the reason for the small number of VRE bacteremia cases developed during 748 colonization days. VRE pneumonia and bacteremia were developed in a patient who had negative rectal swab cultures during follow-up. In two patients with documented VRE colonisation, persistent fever, clinical, radiological and laboratory findings were observed which responded to linezolid, despite a culture-proven infection. Patients colonised with VRE should be treated with antibiotics active against VRE in the case of persistent fever and hemodynamic instability under any antimicrobial therapy as recommended in the guidelines1, 8. A large number of patients colonised with VRE pointed out insufficiency of contact and barrier precautions, cleansing, and number of single-patient rooms in our study, as well. The small number of cases, episodes of FN and bacteremia attacks were the limitations of our study.

Conclusion

Consequently, non-carbapenem-based therapy may be cost-effective as the empirical treatment regimen of FN attacks. Carbapenem-based therapy should be opted as empirical therapy depending on the severity of patients. VRE bacteremia is more likely to develop in patients who undergo invasive procedures, have severe breakdown of mucosal barriers, and prolonged and combined broad-spectrum antibiotics use. In hemodynamically unstable patients who do not respond to antimicrobial treatment, VRE colonisation should be taken into consideration whilst shifting to other antibiotic options.

Acknowledgements

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the subject discussed in the manuscript. This study was approved by an internal ethics committee. We are greatly thankful to Prof. Dr. Andreas Voss and M. D. Onur Karatuna for their valuable recommendations about the manuscript.

References

- 1.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:56–93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo H, Ren F, Zhang D, Ji M. Monitoring report on 341 cases of adverse reactions caused by antitumor drugs. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2012;6:3774–3777. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, et al. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk index: A multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3038–3051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Naurois J, Novitzky-Basso I, Gill MJ, Marti Marti1 FM, Cullen MH, Roila F. Management of febrile neutropenia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:252–256. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray BE, Barlett JG. Enterococci. In: Gorbach SL, Barlett JG, Balcklow NR, editors. Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 1610–1615. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moellering RC. Enterococcus species, Streptococcus bovis, and Leuconostoc species. In: Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 2411–2417. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safdar N, Maki DG. The commonality of risk factors for nosocomial colonization and infection with antimicrobial resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, gram-negative bacilli, Clostridium difficile, and Candida. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:834–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-11-200206040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, et al. 2002 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:730–751. doi: 10.1086/339215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul M, Yahav D, Bivas A, Fraser A, Leibovici L. Anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams for the initial, empirical, treatment of febrile neutropenia: comparison of beta-lactams. The Cochrane Library. 2010:CD005197. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005197.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul M, Yahav D, Fraser A, Leibovici L. Empirical antibiotic monotherapy for febrile neutropenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 57:176–189. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki448. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blay JY, Chauvin F, Le Cesne A, et al. Early lymphopenia after cytotoxic chemotherapy as a risk factor for febrile neutropenia. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullah F, Malik SA, Ahmed J. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and ESBL prevalence in Klebsiella pneumoniae from urinary tract infections in the North-West of Pakistan. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2009;3:676–680. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gedik H, Yahyaodlu M, Yörük G, Fincancý M. Extended-Spectrum [beta]-Lactamase Production Rates of Klebsiella spp. and Escherichia coli Strains Isolated From Infections and Fecal Samples of Healthy People. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2010;18:104–106. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C-C, Lee N-Y, Yan J-J, et al. Bacteremia Due to Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacter cloacae: Role of Carbapenem Therapy. Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;54:3551–3556. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00055-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess DS, Hall RG, II, Lewis JS, II, Jorgensen JH, Patterson JE. Clinical and Microbiologic Analysis of a Hospital's Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Isolates Over a 2-Year Period. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:1232–1237. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.12.1232.32706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abhilash KPP, Veeraraghavan B, Abraham OC. Epidemiology and Outcome of Bacteremia Caused by Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in South India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trecarichi EM, Tumbarello M, Spanu T, et al. Incidence and clinical impact of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase (ESBL) production and fluoroquinolone resistance in bloodstream infections caused by Escherichia coli in patients with hematological malignancies. J Infect. 2009;58:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanamaru A, Tatsumi Y. Microbiological Data for Patients with Febrile Neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;39:7–10. doi: 10.1086/383042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris PG, Hassan T, McNamara M, Hassan A, Wiig R, Grogan L, Oscar S. Breathnach, Edmond Smythand Hilary Humphreys. Emergence of MRSA in positive blood cultures from patients with febrile neutropenia-a cause for concern. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1085–1088. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girou E, Pujade G, Legrand P, Cizeau F, Brun-Buisson C. Selective screening of carriers for control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in high-risk hospital areas with a high level of endemic MRSA. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:543–550. doi: 10.1086/514695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papia G, Louie M, Tralla A, Johnson C, Collins V, Simor AE. Screening high-risk patients for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on admission to the hospital: is it cost effective? Infect Cont Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:473–477. doi: 10.1086/501655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuehnert MJ, Jernigan JA, Pullen AL, Rimland D, Jarvis WR. Association between mucositis severity and vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Inf Cont Hosp Epid. 1999;20:660–663. doi: 10.1086/501561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shay DK, Maloney SA, Montecalvo M, et al. Epidemiology and mortality risk of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bloodstream infections. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]