Abstract

The c-Kit receptor tyrosine kinase is commonly over-expressed in different types of cancer. p53 activation is known to result in the down-regulation of c-Kit. However, the underlying mechanism has remained unknown. Here, we show that the p53-induced miR-34 microRNA family mediates repression of c-Kit by p53 via a conserved seed-matching sequence in the c-Kit 3'-UTR. Ectopic miR-34a resulted in a decrease in Erk signaling and transformation, which was dependent on the down-regulation of c-Kit expression. Furthermore, ectopic expression of c-Kit conferred resistance of colorectal cancer (CRC) cells to treatment with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), whereas ectopic miR-34a sensitized the cells to 5-FU. After stimulation with c-Kit ligand/stem cell factor (SCF) Colo320 CRC cells displayed increased migration/invasion, whereas ectopic miR-34a inhibited SCF-induced migration/invasion. Activation of a conditional c-Kit allele induced several stemness markers in DLD-1 CRC cells. In primary CRC samples elevated c-Kit expression also showed a positive correlation with markers of stemness, such as Lgr5, CD44, OLFM4, BMI-1 and β-catenin. On the contrary, activation of a conditional miR-34a allele in DLD-1 cells diminished the expression of c-Kit and several stemness markers (CD44, Lgr5 and BMI-1) and suppressed sphere formation. MiR-34a also suppressed enhanced sphere-formation after exposure to SCF. Taken together, our data establish c-Kit as a new direct target of miR-34 and demonstrate that this regulation interferes with several c-Kit-mediated effects on cancer cells. Therefore, this regulation may be potentially relevant for future diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: p53, miR-34a, miR-34b/c, c-Kit, migration, chemoresistance, stemness

INTRODUCTION

c-Kit, which is also known as CD117 or stem cell factor receptor, is a type III receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and an important mediator/initiator of several signaling cascades. The c-Kit gene was initially identified as the cellular homolog of v-kit, the oncogene of the Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma virus [1, 2]. Binding of its ligand stem cell factor (SCF, also known as steel factor) leads to receptor homodimerization and autophosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues on the intracellular domain of the receptor, which activates several signaling cascades [3]. Among these are the PI-3, Src, Jak/Stat, and MAP kinase induced pathways, as well as phospholipase C and D mediated signaling [4]. c-Kit exerts numerous functions in hematopoiesis, pigmentation, and gametogenesis and is involved in T-cell differentiation and mast cell regulation as well [4-8]. Deregulated expression and activation of c-Kit contributes to several types of diseases among them cancer [4]. For example, the c-Kit signaling axis is involved in leukemia [9, 10], glioblastoma [11], melanoma [12, 13], lung [14, 15] and breast cancer [16]. However, the role of c-Kit expression in colorectal cancer (CRC) is still largely unknown (see also discussion). Aberrant activation of c-Kit is associated with diminished chemo-responsiveness/chemoresistance of cancer cells and increased oncogenic signaling (e.g. in gastrointestinal stromal tumors [GISTs]) presumably by mediating an escape from apoptotic triggers [17-21]. The ligand of c-Kit, SCF/stem cell factor, is often expressed at elevated levels in tumor cells as well and contributes to the autocrine/paracrine transmission of oncogenic signals [22-25].

Interestingly, the microRNAs (miRNAs) miR-193a, −193b, −221, −222 and −494 are known to repress the expression of c-Kit by directly targeting its mRNA [26-29]. MiRNAs are small non-protein-coding RNAs of ~20-25 nucleotides length, which repress target mRNAs by binding to their 3'-untranslated regions (3'-UTRs) [30].

The p53 tumor suppressor gene encodes a transcription factor, which is activated by numerous cellular stresses, which generally lead to DNA damage [31]. Interestingly, a p53-dependent down-regulation of c-Kit expression has been observed in mice, which occurred in the absence of direct binding of p53 to the c-Kit promoter [32]. Recently, microRNAs have been implicated in the repression of genes by p53 [33]. Among the most prominently p53-induced miRNAs, are the members of the miR-34 family: miR-34a, miR-34b and miR-34c, which are encoded by two different genes [34]. miR-34a/b/c were found to mediate several different tumor suppressive activities of p53, e.g. cell cycle arrest, as well as inhibition of stemness, induced pluripotent stem-cells (IPS), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)/metastasis and metabolism [33]. In addition, miR-34 genes may also be involved in other physiological processes, as for example in aging of the heart [35].

Here we report that miR-34 directly targets the c-Kit mRNA and thereby mediates repression of c-Kit expression by p53. Accordingly, miR-34 activation negatively regulated c-Kit mediated signaling events and cell transformation. Furthermore, miR-34a-mediated chemosensitization was accompanied by down-regulation of c-Kit. In addition, SCF-induced migration and invasion was abrogated by ectopic miR-34. Ectopic expression of c-Kit in CRC lines enhanced the expression of numerous markers of stemness, which was in agreement with an association of elevated c-Kit expression in primary CRC tumors and the expression of stemness markers, such as OLFM4, LGR5, BMI-1 and CD44, whereas ectopic expression of miR-34 significantly reduced the expression of CD44, Lgr5 and BMI-1. An enhancement of stemness by SCF was blocked by ectopic expression of miR-34a. Taken together, our results show that the regulation of c-Kit by miR-34 may critically contribute to the tumor suppressive effects of miR-34, and therefore p53, in CRC and other tumor entities.

RESULTS

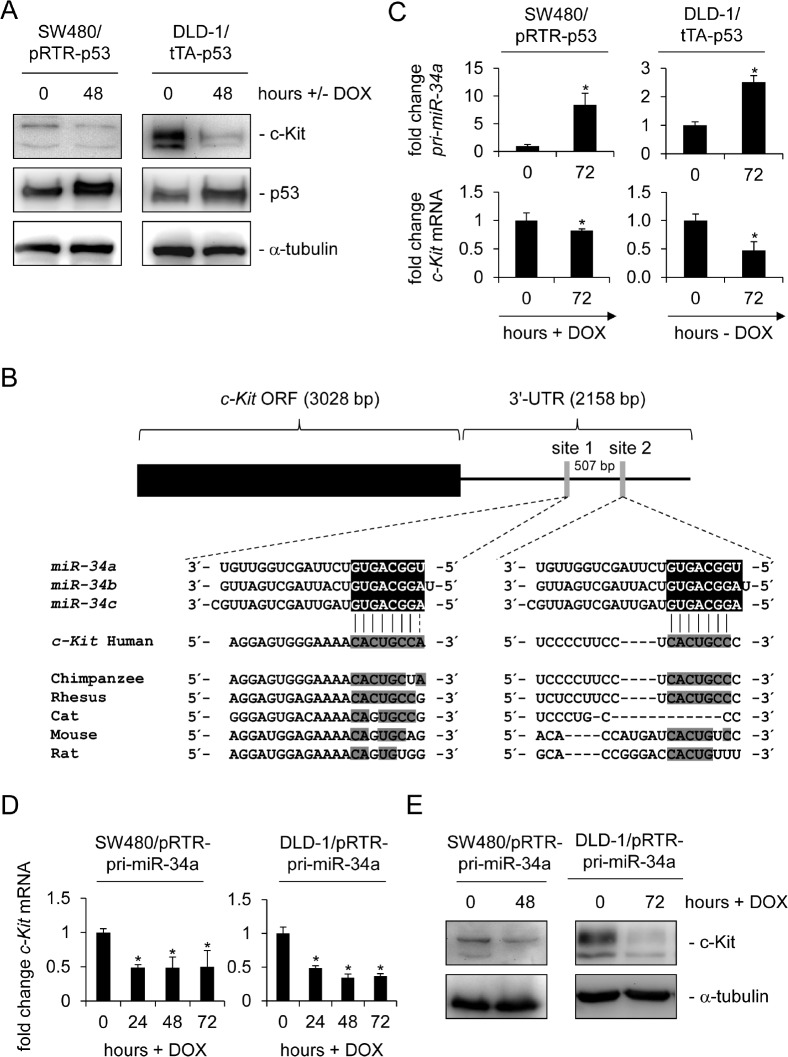

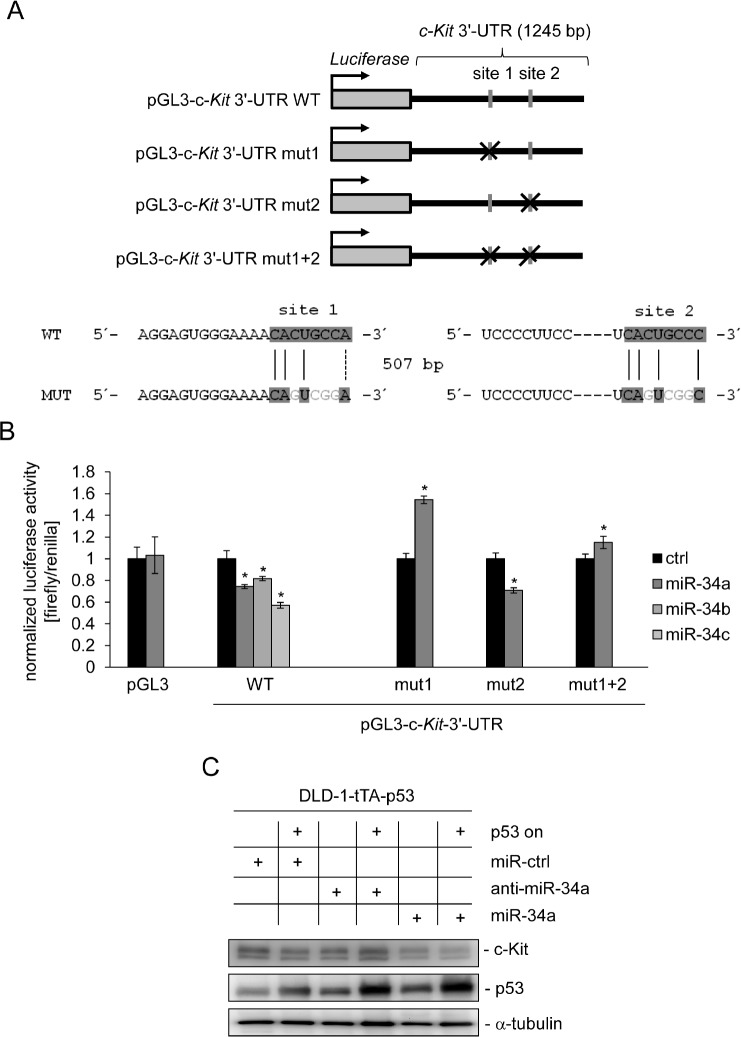

c-Kit is regulated in a p53-dependent manner in colorectal cancer cell lines

Since a recent study reported a p53-dependent regulation of c-Kit, which occurred in the absence of p53 binding to the c-Kit promoter in mice [32], we hypothesized that miR-34 could be the mediator of this effect. In order to investigate this putative connection we used two different systems to conditionally express p53: SW480 cell pools transfected with the doxycycline (DOX) -inducible vector pRTR expressing the p53 open reading frame (ORF) and a DLD-1 single cell clone harboring a p53 allele under control of the tet-off system [36, 37]. Although the endogenous levels of c-Kit were lower in SW480 cells than in DLD-1 cells, activation of p53 in both cellular systems resulted in the down-regulation of c-Kit protein expression (Figure 1A). Since miRNAs were shown to mediate gene repression by p53 we examined the c-Kit 3'-UTR using the Target-Scan algorithm [38]. Thereby we identified two potential miR-34 seed-matching sequences in the 3'-UTR of c-Kit (Figure 1B). While the first site (which is a perfect match to the miR-34a 8-mer seed-matching sequence) is relatively conserved among different species, the second site seems to be less conserved. In line with previous reports, expression of the primary miR-34a transcript was induced and the c-Kit mRNA was repressed after p53 activation in both SW480 and DLD-1 cells (Figure 1C). Since the expression of miR-34b and miR-34c is at least 100 fold lower than that of miR-34a [39-41] in CRC cells and cell lines we focused our further studies on miR-34a. Notably, the ectopic expression of miR-34a driven by a conditional, episomal vector was sufficient to reduce c-Kit expression at the mRNA and protein levels in SW480 and DLD-1 cells (Figure 1D and 1E). Similar results were obtained with the CRC cell line HCT15 harboring the same miR-34 expression vector, though miR-34a mediated regulation was not as pronounced as in the other two cell lines (Supplemental Figure 1A and B). In order to determine whether miR-34 directly binds to the seed-matching sequences mentioned above we placed the c-Kit 3'-UTR (including the two potential binding sites) downstream of a luciferase open reading frame (Figure 2A). In a dual-reporter luciferase assay miR-34a as well as miR-34b and c significantly decreased the activity of this reporter (Figure 2B). When the seed-matching sequence in site 1 was mutated, the reporter was resistant to down-regulation by miR-34a, whereas mutation of site 2 did not affect the miR-34-mediated down-regulation of the reporter. Mutation of both sites led to resistance against miR-34a regulation. These results indicate that the miR-34 family directly targets the c-Kit 3'-UTR via site 1. This result is in accordance with the higher degree of conservation of site 1 when compared to site 2. Furthermore, p53-mediated down-regulation of c-Kit in DLD-1 cells could be prevented by simultaneous transfection of an antagomiR directed against miR-34a (anti-miR-34a), while additionally transfected miR-34a further enhanced the repression of c-Kit when p53 was activated concomitantly (Figure 2C). Taken together, miR-34a therefore mediates the repressive effects of p53 on c-Kit expression by directly targeting the c-Kit 3'-UTR via a single conserved seed-matching sequence.

Figure 1. c-Kit is repressed after ectopic p53 and miR-34a expression in colorectal cancer cell lines.

(A) Western blot analysis of c-Kit protein levels after induction of p53 in colorectal cancer cell lines SW480 and DLD-1. α-tubulin served as a loading control. (B) Scheme of the c-Kit mRNA and conservation of the putative miR-34 seed-matching sequences, which are represented as grey vertical bars. Detailed sequences of the two sites and phylogenetic homologies are shown below. Potential base pairing is shaded in grey. (C) qPCR analysis of pri-miR-34a and c-Kit mRNA levels in the colorectal cancer cell lines SW480 and DLD-1 after induction of p53 by addition or withdrawal of doxycycline (DOX) for 72 hours. Results were normalized to β-actin mRNA. (D) qPCR analysis of c-Kit mRNA in the colorectal cancer cell lines SW480 and DLD-1 carrying the inducible pRTR/pri-miR-34a vector after addition of doxycycline. E) Detection of c-Kit protein by Western blot analysis after induction of pri-miR-34a in the indicated cells. α-tubulin served as a loading control. C+D: results represent the mean +/−S.D. (n=3).

Figure 2. miR-34a directly targets c-Kit and mediates c-Kit repression by p53.

(A) Scheme of constructs used for dual luciferase assays. The positions of the putative miR-34 seed-matching sequences in the c-Kit 3'-UTR are depicted as a grey vertical bars, their mutations as crosses. Sequences of the respective targeted mutations are given below. (B) Dual reporter assay in SW480 cells transfected with miR-34a/b/c mimics or control oligonucleotide and the indicated 3'-UTR-reporter constructs for the human c-Kit 3'-UTR. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). (C) DLD-1/tTA-p53 cells were either transfected with a control oligonucleotide, miR-34a or an antagomiR directed against miR-34a for 24 hours either in the presence or absence of DOX (without or with ectopic p53). Expression of the indicated proteins was detected by Western blot analysis. α-tubulin served as a loading control.

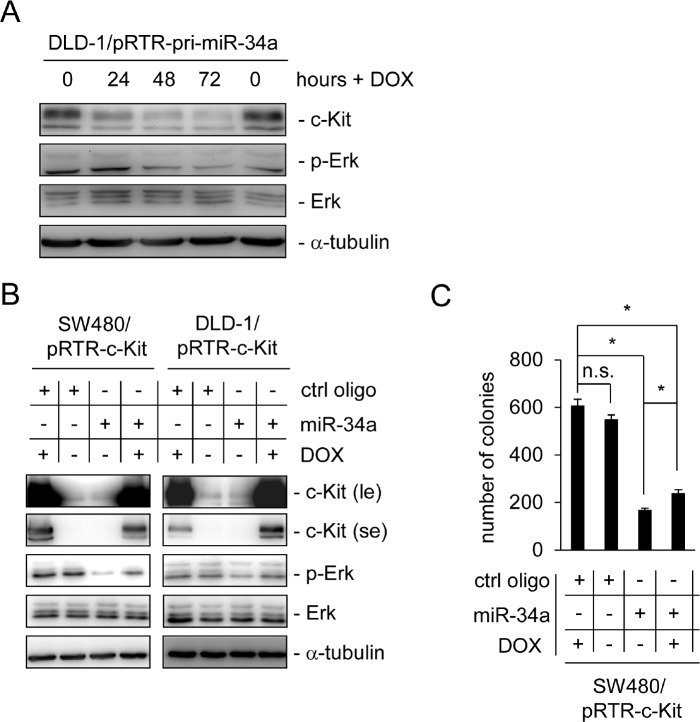

miR-34a inhibits Erk signaling and colony formation by down-regulation of c-Kit

In order to determine the consequences of a miR-34a-mediated decrease in c-Kit protein we analyzed Erk signaling, which is known to be activated by c-Kit. Indeed, the levels of phosphorylated Erk were decreased following the induction of ectopic miR-34a expression in DLD-1 cells, which was accompanied by a reduction in the levels of c-Kit protein, whereas the total amount of Erk protein levels was not affected (Figure 3A). Next, we determined whether the miR-34a-mediated decrease in Erk-phosphorylation was dependent on the down-regulation of c-Kit. Therefore, we generated pools of DLD-1 and SW480 cells carrying a conditional expression vector for c-Kit lacking its original 3'-UTR and therefore a miR-34 seed matching sequence. Ectopic miR-34a expression resulted in decreased levels of Erk-phosphorylation in both cell lines, while the control oligo had no effect (Figure 3B). Notably, induction of ectopic c-Kit largely reversed the effect of miR-34a on phosphorylated Erk, whereas the amount of total Erk was not affected. Collectively, these results show that the down-regulation of c-Kit is necessary for the inhibitory effects of miR-34a on mitogenic Erk signaling.

Figure 3. Ectopic c-Kit overrides miR-34a-dependent inhibition of Erk signaling and colony formation in soft agar.

(A) DLD-1/pRTR-pri-miR-34a cells were treated with DOX for the indicated time-points. The indicated proteins were detected by Western blot analysis. α-tubulin served as a loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of the indicated SW480 and DLD-1 cells after oligonucleotide transfection for 48 hours and addition of DOX for 24 hours. α-tubulin served as a loading control. le = long exposure, se = short exposure. (C) Soft agar colony formation assay. The indicated cells were treated as described under (B). Results represent the mean +/−S.D. (n=3) and significance was calculated applying a Student's t-test.” * “: p < 0.05.

To test whether these regulations would affect the capacity of SW480 cells to grow in soft agar, which is known to be affected by Erk-signaling [42], cells treated as in Figure 3B were seeded into soft agar and colony formation was measured (Figure 3C). Indeed, miR-34a transfection severely reduced the number of colonies. Furthermore, induction of ectopic c-Kit expression led to a slight but significant increase in the number of colonies, at least partially reflecting the results observed on the level of Erk phosphorylation. Therefore, signaling downstream of c-Kit contributes to colony formation and can be suppressed by miR-34a via down-regulation of the c-Kit receptor expression. We also analyzed the expression of the EMT marker genes E-cadherin and Vimentin as well as the primary transcript of miR-34a upon ectopic c-Kit expression in DLD-1 and SW480 cells (Supplemental Figure 1C and D). We did not detect any significant changes of these mRNAs, although recent publications implied a role of c-Kit in EMT [43, 44].

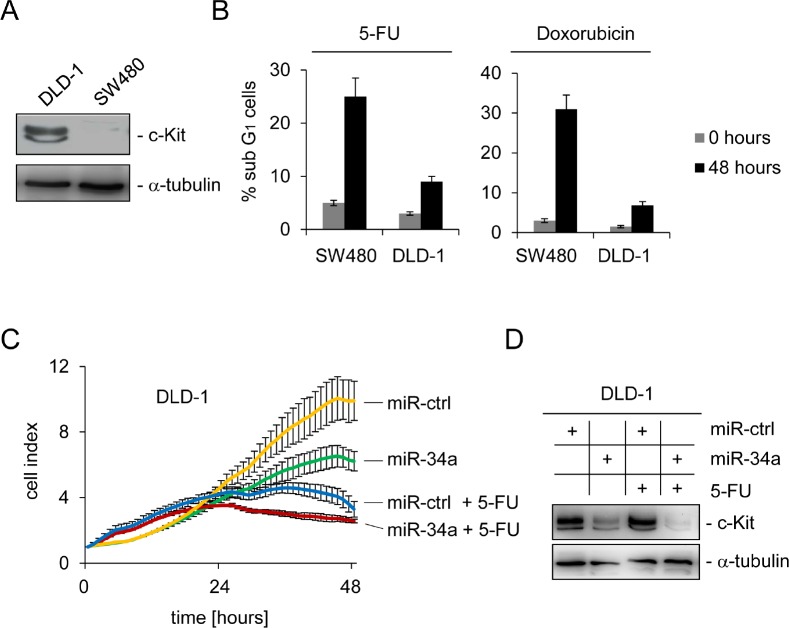

The interplay between miR-34a and c-Kit influences chemo-sensitivity

Recently, c-Kit was shown to mediate chemo-resistance in ovarian tumor initiating cells [19]. Therefore, we asked whether c-Kit might play a similar role in colorectal cancer. To address this issue DLD-1 cells, which express high levels of endogenous c-Kit, and SW480 cells expressing low levels of c-Kit were compared (Figure 4A). After treatment of both cell lines with either the anti-metabolite 5-FU or the anthracycline antibiotic Doxorubicin for 48 hours, SW480 cells showed a more pronounced apoptotic response to the treatment with both chemo-therapeutics, as determined by DNA content analysis using flow-cytometry, than DLD-1 cells (Figure 4B): upon treatment with the 5-FU the apoptotic sub-G1 fraction of cells was elevated about five times (from five to 25 %) in SW480 cells, while it tripled in DLD-1 cells (from three to nine %). Similar results were observed with Doxorubicin treatment: while SW480 cells showed a 10 fold increase (from three to 31 %) of apoptosis, apoptosis in DLD-1 cells increased about 3.5 fold (2 to 7 %). Consistently, the rate of spontaneous apoptosis in untreated cells was higher in SW480 cells than in DLD-1 cells, which therefore also inversely correlated with the level of c-Kit expression.

Figure 4. c-Kit and miR-34a modulate the apoptotic response to chemotherapeutic agents.

(A) Detection of endogenous c-Kit levels by Western blot analysis of DLD-1 and SW480 colorectal cancer cells. Detection of α-tubulin served as loading control. (B) Cells were treated with either 5-FU or Doxorubicin for 48 hours and subjected to DNA content analysis by flow cytometry. Results represent the mean +/−S.D. (n=3). (C) DLD-1 cells were transfected with the indicated oligonucleotides and simultaneously treated with 5-FU or water. The cell index, which corresponds to cell proliferation, was determined by real-time impedance measurements. (D) Cells treated as described in (C) were subjected to Western blot analysis. α-tubulin served as loading control.

In order to determine whether the relative chemo-resistance of DLD-1 cells is based on high levels of c-Kit and can therefore be influenced by miR-34a, DLD-1 cells were transfected with miR-34a or control oligos for 24 hours to achieve c-Kit down-regulation. Thereafter, cells were treated with either 5-FU or left untreated and the cell index was measured continuously over two days by real-time impedance measurements. Cells transfected with the control oligo appeared unaffected and transfection with miR-34a resulted in a lower cell index over time (Figure 4C). Treatment with 5-FU affected the survival of cells even stronger but the most drastic effect resulted from the combined treatment with miR-34a and 5-FU. As expected, ectopic miR-34a resulted in a severe decrease of c-Kit protein levels in DLD-1 cells, whereas the control oligonucleotide did not influence expression of c-Kit protein (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results show that high levels of c-Kit promote chemo-resistance of CRC cells to 5-FU and Doxorubicin, respectively. This is probably due to reduction of the apoptotic response. miR-34a can inhibit this effect via down-regulation of c-Kit and therefore sensitize cells to chemotherapeutic treatment.

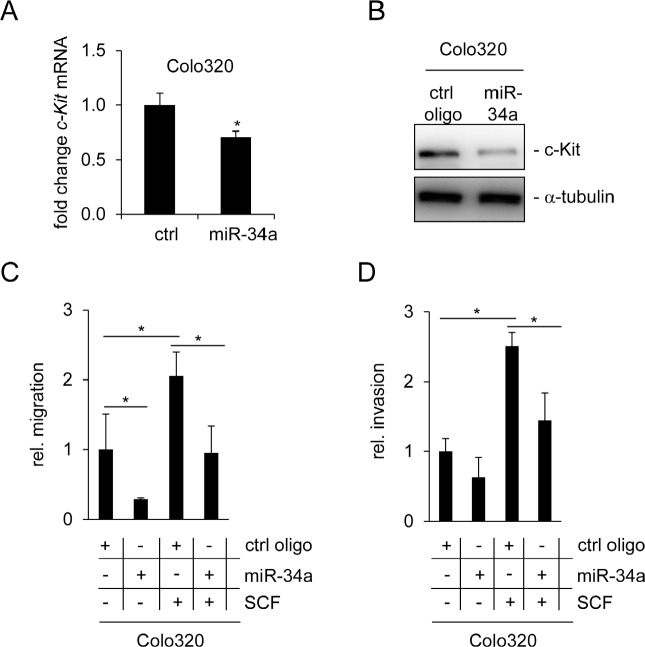

Disruption of the SCF/c-Kit axis by miR-34a inhibits migration and invasion

Another function of the SCF/c-Kit axis is an enhancement of migration, which was previously observed after treatment of the CRC cell line Colo320 with SCF [45]. Therefore, we analyzed whether transfection of Colo320 cells with miR-34a may interfere with the effects of SCF. First, regulation of c-Kit by miR-34a was confirmed on mRNA and protein level (Figure 5A and B). As expected, transfection of Colo320 cells with miR-34a oligonucleotides for 48 hours led to a decrease of c-Kit on the mRNA and protein levels. As determined by a modified Boyden chamber assay, the ectopic expression of miR-34a resulted in a decrease in cell migration (Figure 5C). Conversely, when cells were treated with SCF, the number of migrating cells doubled, confirming results described by Yusada et al. [45]. Combined treatment of Colo320 cells with SCF and miR-34a mimetics significantly reduced migration approximately to the levels observed in the controls. miR-34a had similar inhibitory effects on basal invasion and SCF-induced invasion of Colo320 cells (Figure 5D). A likely explanation for these effects is that miR-34a interferes with SCF signaling by suppressing the expression of the c-Kit receptor which could render cells refractory to SCF.

Figure 5. miR-34a inhibits basal and SCF-induced migration and invasion of Colo320 cells.

(A) Colo320 CRC cells were transfected either with a control (ctrl) or a miR-34a oligonucleotide for 48 hours. qPCR analysis was used to determine c-Kit mRNA levels. (B) Detection of c-Kit protein levels by Western blot analysis 48 hours after oligonucleotide transfection. α-tubulin served as loading control. (C) Colo320 cells were transfected with the indicated oligonucleotides and simultaneously treated with SCF (or water) for 24 hours. Thereafter cells were seeded into Boyden chambers to determine migration. (D) Determination of invasion using a Boyden chamber assay. Cells were treated as in (C). (A,C,D) Results represent the mean +/−S.D. (n=3) and significance was calculated applying a Student's t-test.” * “: p < 0.05.

Interestingly, we observed no change in the expression of EMT markers (Vimentin, CDH1, Occludin and Fibronectin) in Colo320 cells after ectopic miR-34a expression (Supplemental Figure 1E). This suggests that the underlying mechanism is not related to the induction of MET by miR-34a, which was previously shown to occur in CRC cells [36]. Also expression of pri-miR-34a was not affected by c-Kit activation, excluding the presence of a feed-back loop, which was recently described for miR-34 and its target Snail [36].

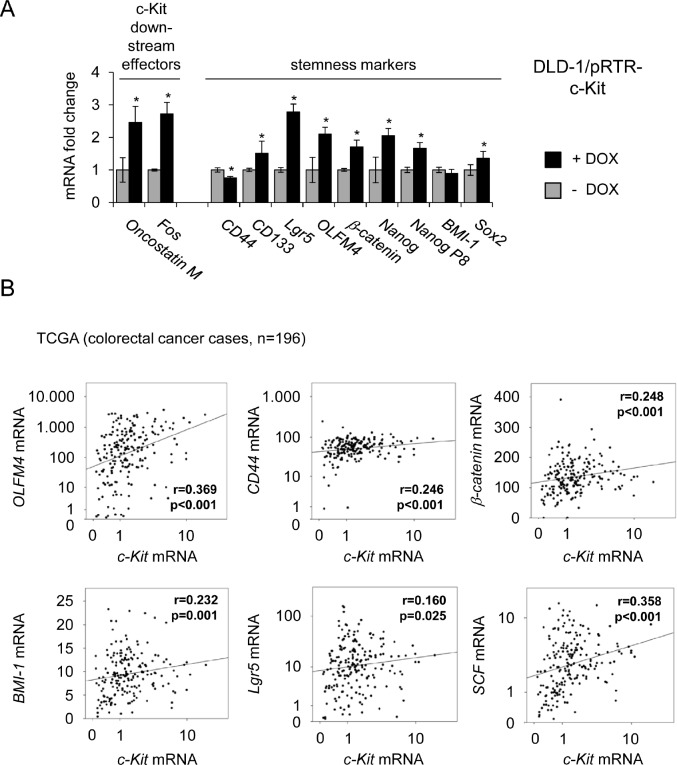

Association of c-Kit with markers of CRC stemness

Since SCF is involved in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cells [46] and recent studies indicated a role for c-Kit in stemness in ovarian cancer [19], we asked whether c-Kit influences the expression of stemness markers in colorectal cancer cells. Therefore, c-Kit was ectopically expressed in DLD-1 cells and changes in mRNA expression were determined by qPCR. As positive controls for c-Kit-mediated gene regulations, expression of its downstream effectors c-Fos and Oncostatin M [47, 48], was analyzed. As markers for CRC stemness the expression of CD44, CD133, Lgr5, Nanog, Nanog P8, β-catenin, Sox2, BMI-1 and OLFM4 was determined [49-53]. As expected, c-Fos and Oncostatin M were induced after c-Kit activation (Figure 6A). Besides CD44 and BMI-1, all analyzed stemness markers were significantly up-regulated by c-Kit. CD44 was repressed and BMI-1 remained unchanged. These results indicate that c-Kit might enhance stemness of colorectal cancer cells. Next, we determined whether an association between c-Kit and stemness markers may also be present in clinical samples obtained from CRC patients as well. Therefore, expression data of 196 colorectal tumors from the public database TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas, [54]) was analyzed (Figure 6B). From these analyses, the expression of OLFM4, CD44, β-catenin, BMI-1 and Lgr5 mRNA emerged as significantly associated with elevated c-Kit mRNA expression (p ≤ 0.05). Additionally, elevated c-Kit ligand (SCF/stem cell factor) expression correlated with high receptor expression. This confirms previous results describing a co-expression of receptor and ligand [22-25]. Collectively, these associations suggest that c-Kit or/and presumably factors regulating c-Kit, as miR-34, might play a role in the regulation of stemness in colorectal cancer.

Figure 6. Ectopic c-Kit induces expression of stemness markers and correlates with their expression in primary CRC.

(A) DLD-1/pRTR-c-Kit cells were treated with DOX for 48 hours. Expression of the indicated mRNAs was determined by qPCR. Results represent the mean +/−S.D. (n=3).” * “: p < 0.05. (B) mRNA expression data derived from primary CRC samples (n = 196) were obtained from the public database TCGA [54]. Correlation coefficients and p-values were calculated applying the Spearman correlation algorithm. Scatter plots show the respective correlations. Both, the c-Kit levels on the x-axes and the y-axes of the OLFM4, CD44, Lgr5 and SCF mRNA expression values are provided as log10 scale.

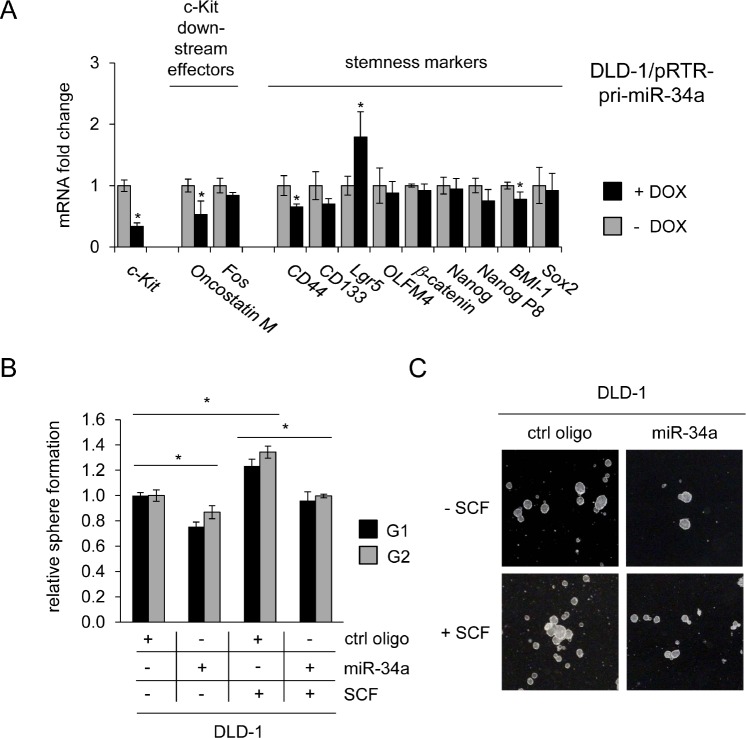

miR-34 interferes with SCF-induced stemness

To investigate whether miR-34a-dependent regulation of c-Kit might affect c-Kit-induced stemness markers, miR-34a was ectopically expressed in DLD-1 cells by activation of a conditional pRTR-pri-miR-34a vector (Figure 7A). The mRNA levels of c-Kit and its published downstream effectors c-Fos and Oncostatin M were repressed upon activation of miR-34a expression. However, mRNAs representing stemness markers displayed relatively weak down-regulations upon induction of miR-34a. In order to determine whether these regulations are relevant for stemness-related properties on the cellular level, DLD-1 cells were subjected to a sphere formation assay (Figure 7B). This assay in which cells grow in suspension under non-adherent conditions can be used to evaluate self-renewing capacities of cancer stem cells and has been applied previously for analyzing the effect of miR-34 on gastric cancer stem cells [55]. In line with previous publications [56] treatment with SCF significantly stimulated sphere-formation of DLD-1 cells. In contrast, treatment with miR-34a oligonucleotides reduced the number of spheres and also suppressed SCF-induced sphere formation of DLD-1 cells (Figure 7B and C). These effects were consistently observed over two consecutive generations. Taken together, these results show that miR-34a suppresses sphere formation and therefore stemness of colorectal cancer cells by targeting c-Kit.

Figure 7. Role of the miR-34a/c-Kit axis in the regulation of stemness markers and sphere formation.

(A) DLD-1 cells pRTR/pri-miR-34a were treated with DOX for 48 hours. Expression of the indicated mRNAs was analyzed by qPCR. (B) DLD-1 cells were transfected with the indicated oligonucleotides and treated with SCF (or water) and subjected to a sphere formation assay. Sphere numbers were determined after seven days for the first generation (G1) and seven days after seeding for G2. Treatment with oligonucleotides and SCF was repeated when cells were passaged. (C) Representative pictures of DLD-1 derived G1 spheres, magnification: 40x. (A,B) Results represent the mean +/−S.D. (n=3) and significance was calculated applying a Student's t-test.” * “: p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

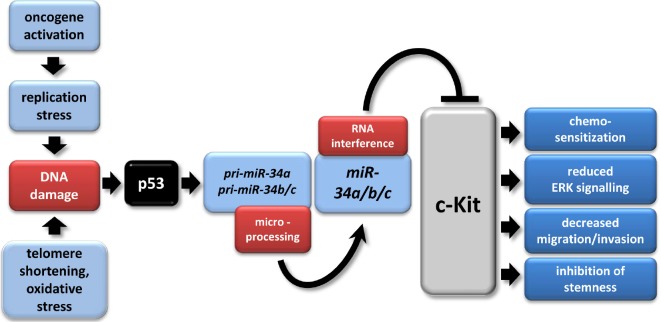

In this study c-Kit was identified as a new target of the miR-34 family. Since c-Kit plays a role in numerous cancer-associated pathways, these results extend the tumor suppressive mechanisms of miR-34. A model summarizing our findings is shown in Figure 8. miR-34-mediated down-regulation of c-Kit resulted in diminished Erk-phosphorylation levels, which was associated with decreased colony formation in soft agar and therefore a decrease in cellular transformation. Moreover, low endogenous c-Kit protein levels or a decrease in c-Kit caused by ectopic miR-34 were associated with increased chemosensitivity. Furthermore, miR-34a inhibited migration and invasion and also SCF-mediated enhancement of these processes was blocked by miR-34a. Finally, activation of c-Kit induced several stemness markers in CRC cell lines and was associated with their expression in primary CRC tumors, whereas activation of miR-34a in CRC cell lines resulted in a down-regulation of c-Kit and c-Kit-induced markers, and suppressed sphere-formation of CRC cells, indicating that CRC stemness may be controlled by the miR-34/c-Kit axis.

Figure 8. The p53/miR-34/c-Kit axis.

The model depicts multiple tumor suppressive effects of miR-34a directly targeting c-Kit which were identified in this study. In tumors, p53 mutation/inactivation or CpG methylation of miR-34a/b/c promoters may abrogate this pathway [33, 91, 92]. miR-34a/b/c have multiple other targets besides c-Kit [33, 93]. The model was adapted from [94].

Our studies were mainly carried out in colorectal cancer cells, which have been previously shown to express c-Kit [17, 45]. However, the role of c-Kit in patients with colorectal cancer is unclear and former studies described divergent results: Friedrichs et al found elevated c-Kit expression to be rare (17.1%) in colorectal carcinomas [57], which was in accordance with other studies which found c-Kit to be expressed at very low levels in colorectal cancer samples using different techniques [58, 59]. Further studies found c-Kit expression in 59% of stage II colorectal cancer patients [60], in 90% of normal colon mucosa and 30% of neoplastic tissues [61] and in 15% of primary colorectal tumors and 14% of distant metastases [62]. Though these results in patients are not uniform, c-Kit presumably has a function in colorectal cancer cells since the c-Kit receptor as well as its ligand are expressed at elevated levels in colorectal cancer cell lines [63]. In support of this, SCF stimulates anchorage independent growth in four out of five CRC cell lines [56] and increases migration of CRC cell lines [45]. Furthermore, aberrant activation of the c-Kit axis suppresses apoptosis and stimulates invasion of DLD-1 colorectal cancer cells [17].

We could show that miR-34a antagonizes SCF, presumably by targeting c-Kit and therefore interrupting the signaling pathways down-stream of c-Kit which are responsible for the changes in cell behavior. Noteworthy, ectopic c-Kit did not affect the expression of EMT markers, such as CDH1/E-cadherin or Vimentin. This was surprising, since previous publications have linked c-Kit with EMT, which is an important step in the metastatic cascade [43].

Our results indicate that c-Kit expression is associated with chemo-resistance, which can be partially reverted by ectopic miR-34a. This is reminiscent of the effect of Imatinib (STI571), which also targets c-Kit and was shown to be therapeutically effective against gastrointestinal stromal tumors/GIST [64, 65]. Imatinib renders DLD-1 cells, which express high c-Kit levels, more responsive to the cytotoxic effect of 5-FU [66]. Therefore, the additive effect of c-Kit inhibition and 5-FU has precedence and should be studied further, since this would potentially allow to reduce the dose of chemotherapeutic compounds in the future. miR-34 mimetics were previously shown to sensitize cells belonging to other tumor entities, such as breast, prostate, gastric and lung cancer towards chemotherapy [67-70]. Therefore, miR-34 mimetics represent promising candidates for clinical applications [71].

Furthermore, we found that c-Kit activation results in the up-regulation of several stemness markers in colorectal cancer cells and primary tumors. This is in accordance with previous findings, which show that colorectal cancer stem cells display increased resistance towards chemotherapeutics such as 5-FU [72, 73]. c-Kit was suggested to activate ABCG2 drug transporters to confer chemoresistance in ovarian cancer [19] which might explain why stem cells are resistant to a variety of agents, rather than to one single chemotherapeutic agent [49].

Interestingly, previous publications revealed that miR-221 and 222 regulate angiogenic processes via targeting c-Kit [74]. Since miR-34a targets c-Kit as well, effects of p53 on tumor-angiogenesis may be mediated, at least in part, via miR-34.

Recently, other RTKs were identified as targets of miR-34, for example Axl, c-Met, PDGFR α and β [49, 55, 75, 76], suggesting a coordinated inhibition of RTKs by miR-34. According to the microRNA target prediction algorithms targetSCAN and Miranda [72, 73], most of the potential miR-34-regulated RTKs cluster in class III [50], among them PDGFR α, PDGFR β and c-Kit.

Since both, miR-34a and c-Kit interact with numerous signaling pathways, more detailed analyses are necessary in order to illuminate the different aspects and consequences of this regulation. For instance activation of c-Kit is not only associated with cancer but seems to play a role in allergic asthma as well [6]. Recently, miR-34a was shown to interfere with mTOR signaling pathway and thereby to play a role in mast cell survival – a process critical in allergic disorders [77]. Moreover, TGF-β was reported to suppress miR-34 thereby leading to secretion of the chemokine CCL22, which is a direct target of miR-34 and recruitment of regulatory T cells [78]. These findings place miR-34 in the context of allergic disorders and miR-34-dependent down-regulation of c-Kit might therefore be important for understanding and treating these diseases as well. Interestingly, inhibition of different RTKs and particularly c-Kit seems to affect asthma [79, 80], via decreasing histamine levels, infiltration of mast cells and eosinophils, interleukin-4 production and airway hyper-responsiveness [81].

Replacement therapy with miR-34a mimetics was successful in several preclinical studies using mouse models of cancer and may therefore represent a therapeutic option for the treatment of several tumor entities in the future [82-86]. Our results indicate that c-Kit may be up-regulated in tumors due to inactivation of miR-34 either by CpG methylation or p53 mutations/inhibition. Such tumors may be especially sensitive to a replacement of miR-34 using mimetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatments

The colorectal cancer cell lines SW480 and DLD-1 were kept in DMEM and McCoy's medium, respectively. Colo320 and HCT15 cells were kept in RPMI medium. If not indicated differently, all media were supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen). All cells were cultivated in the presence of 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. Cells were transfected with the episomal expression vector pRTR [87] using Fugene6 (Roche). Polyclonal cell pools were generated by selection with puromycin (2 μg/ml) for 10 days. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined 72 hours after addition of doxycycline (DOX) at a final concentration 100 ng/ml. Transfection of cells with antagomiRs, pre-miRNAs/mimics and respective negative controls (Ambion) was performed using HiPerfect (Qiagen) at a final oligonucleotide concentration of 50 nM. Treatment of cells with 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU, Sigma-Aldrich) was conducted at a concentration of 20 μg/ml, while Doxorubicin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a concentration of 0.25 μg/ml. 5-FU, a pyrimidine analog and anti-metabolite [88] trademarked as Efudex, and the anthracycline antibiotic Doxorubicin [89] are often used for chemotherapy. SCF (ImmunoTools) was used at a final concentration of 10 ng/ml.

Western Blot Analysis

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were performed according to standard protocols. Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate, complete mini protease inhibitors (Roche) and PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche)). Lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 16.060 g for 20 min at 4°C. Per lane 60-100 μg of whole cell lysate was separated using 7.5% SDS-acrylamide gels and transferred on Immobilon PVDF membranes (Millipore). ECL signals were recorded using a CF440 Imager (Kodak). Antibodies used for detection of the indicated proteins are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Generation of a c-Kit expression vector

The vector pWPTet containing the coding sequence of human c-Kit was kindly provided by Matthias Mayerhofer. The coding sequence was excised using BamHI and SpeI, cloned into the shuttle vector pUC19SfiI and ligated into pRTR, respectively via the SfiI sites. The sequence was verified by sequencing. The generation of pRTR vectors containing p53 and pri-miR-34a was described previously [52]. A list of all plasmids used in this paper is provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of DNA content/apoptosis and GFP/RFP expression

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (2×105 cells/well) and cultured in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml DOX. For flow cytometry, cells were trypsinized after 72 hours for GFP/RFP analysis, washed and resuspended in PBS. For detection of GFP expression 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed with a C6 Flow Cytometer Instrument (BD Accuri). For DNA content analysis (1×105) SW480 cells were seeded per 6-well and transfected with 50nM of miR-34a or control oligo. After 24 hours cells were treated with DOX (final concentration 100 ng/ml [Sigma]) or water and incubated for another 48 hours until harvesting. Floating cells and trypsinized cells were collected by centrifugation at 1200 rpm (600 g) for 5 minutes, fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol and stored over night on ice. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.5 ml FACS solution (PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 60 mg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and 0.5 mg/ml RNase) was added per sample and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. DNA content was determined analyzing 10,000 cells per sample using a C6 device (Accuri, Erembodegem, Belgium) and three independent samples per treatment.

Cloning of the c-Kit 3'-UTR

The 3'-UTR of c-Kit mRNA containing putative miR-34a binding sites was PCR-amplified from oligo-dT-primed cDNA from human diploid fibroblast cells with the Verso cDNA kit (Thermo Scientific). The 3'-UTR was cloned into pGL3-control-MCS [90] and verified by sequencing. Mutagenesis of seed sequences was done with the QuickChange Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotides used for cloning and mutagenesis are provided in Supplemental Table 3.

Dual Luciferase Reporter Assays

SW480 cells were seeded in 12-well format at 1×104 cells/well, and transfected after 48 hours with 100 ng of the indicated firefly luciferase reporter plasmid, 20 ng of Renilla reporter plasmid for normalization and 25 nM of miR-34a/b/c pre-miRNA (Ambion, PM11030) or a negative control oligonucleotide (Ambion, neg. control #1). Luciferase assays were carried out after 48 hours with the Dual Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega) according to manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence intensities were measured with a luminometer (Berthold) in 96-well format and analyzed with the Simplicity software package (DLR).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was prepared with the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche) according to manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA per sample using anchored oligo-dT primers (Verso Kit, Thermo Fischer). All results were normalized to β-actin. Per time point/condition three independent experiments were conducted. RT-qPCR was performed using the LightCycler (Roche) and the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). A list of qPCR-primers used for this study is provided in Supplemental Table 4.

Soft agar colony formation assay for anchorage-independent growth

The bottom of a 12-well was coated with 700 μl base agar containing 0.8% low melt agarose (Lonza) which was then covered with 700 μl 0.4% agarose containing 2,000 SW480 cells, either transfected with miR-34a or control oligo 24 hours before, and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. 24 hours later, 250 μl medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added supplemented with either doxycycline (final concentration 100 ng/ml [Sigma]; stock solution 100 μg/ml in water) or vehicle (water). Cells were incubated for 14 days changing the media every 3 days. For determination of colony numbers cells were stained with 500 μl of 0.005% crystal violet per well for 2 hours and de-stained in PBS over night at 4°C. Pictures were taken using an EOS 400D camera (Canon) and colonies were counted using image J software (NIH).

Real-time impedance measurement

A real-time cell analyzer (RTCA) (xCelligence RTCA SP; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany) was used to assess cellular impedance according to manufacturer's instructions. 5000 cells were seeded into each well of an E-plate 16. The seeded cells were allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 minutes in the tissue culture incubator, then transfected or treated with doxycycline respectively before electrode resistance/impedance was recorded every 60 minutes. After 24 hours 5-FU was administered. The measurement was done every 60 minutes for 48 hours. The electrical impedance is represented as a dimension/unit-less parameter termed cell-index, which represents the relative change in electrical impedance that occurs in the presence and absence of cells in the wells. This change is calculated based on the following formula: CI = (Zi −Z0)/15, where Zi determines the impedance at an individual experimental time point and Z0 is the impedance measured at the beginning of the experiment. The impedance is measured at three different frequencies (10, 25 or 50 kHz) (ref: Roche Diagnostics GmbH. Introduction of the RTCA DP Instrument. RTCA DP Instrument Operator's Manual, A. Acea Biosciences, Inc.; 2008.).

Migration and invasion assays in Boyden chambers

In order to investigate the changes in motility Colo320 cells were seeded into six-well plates and immediately transfected with either miR-34a or a control oligo [100 nM each] and treated with SCF [10 ng/ml] or vehicle. After 24 hours cells were seeded into Boyden chambers (Corning) either coated (invasion) or uncoated (migration) with Matrigel (BD Bioscience) at a dilution of 3.3 ng/ml in medium without serum. Medium was supplemented with SCF for stimulated cases. Cells were allowed to migrate for 48 hours, then non-motile cells at the top of the filter were removed and the cells in the bottom chamber were fixed with methanol and stained with DAPI. Per membrane, the cell number was determined in five fields by fluorescence microscopy.

Sphere formation assay

For induction of sphere formation adherent DLD-1 cells were trypsinized and 1 × 105 cells were seeded into a six-well coated with attachment preventing PolyHEMA (Sigma) using 5 ml sphere-medium consisting of DMEM-F12 + GlutaMAX-I (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 supplement (1:50; Invitrogen), EGF (20 ng/ml; R&D Systems), BSA (0.4 %, Sigma) and insulin (4 μg/ml; Invitrogen). [75]. Immediately after seeding the cells were transfected with either a control oligo or miR-34a [200 nM] and treated with either water or SCF [10ng/ml]. Resulting spheres were trypsinized again and quantified as well as employed for a second generation. For quantification 1 × 104 cells/well were seeded in sphere-medium containing 1 % methyl cellulose (Sigma) into PolyHEMA coated 96-well plates (at least six wells per unicate). The number of colonies larger than 50 μm in diameter was determined after seven days. Representative pictures were taken using an EOS 400D camera (Canon) at 40 fold magnification.

Statistical analysis

For analysis of patient data calculations were conducted using SPSS software 19 (SPSS Inc.). For the comparison of the expression data the Spearman correlation algorithm was applied for the generation of the correlation coefficient (r) and statistical significance (p-value). Correlations were illustrated by generating scatter/dot plots using the SPSS chart builder tool. A partial regression line was added in order to emphasize the respective correlation. For most assays a Student's t-test was applied to determine significance if not indicated otherwise. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Figure and Tables

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthias Mayerhofer for kindly providing plasmids. H.H.'s lab is supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe, the DFG, the Rudolf-Bartling-Foundation and the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK).

REFERENCES

- 1.Besmer P, Murphy JE, George PC, Qiu FH, Bergold PJ, Lederman L, Snyder HW, Jr, Brodeur D, Zuckerman EE, Hardy WD. A new acute transforming feline retrovirus and relationship of its oncogene v-kit with the protein kinase gene family. Nature. 1986;320(6061):415–421. doi: 10.1038/320415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarden Y, Kuang WJ, Yang-Feng T, Coussens L, Munemitsu S, Dull TJ, Chen E, Schlessinger J, Francke U, Ullrich A. Human proto-oncogene c-kit: a new cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase for an unidentified ligand. EMBO J. 1987;6(11):3341–3351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson DM, Lyman SD, Baird A, Wignall JM, Eisenman J, Rauch C, March CJ, Boswell HS, Gimpel SD, Cosman D, et al. Molecular cloning of mast cell growth factor, a hematopoietin that is active in both membrane bound and soluble forms. Cell. 1990;63(1):235–243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90304-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lennartsson J, Ronnstrand L. Stem Cell Factor Receptor/c-Kit: From Basic Science to Clinical Implications. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1619–1649. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00046.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothschild G, Sottas CM, Kissel H, Agosti V, Manova K, Hardy MP, Besmer P. A role for kit receptor signaling in Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2003;69(3):925–932. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnamoorthy N, Oriss TB, Paglia M, Fei M, Yarlagadda M, Vanhaesebroeck B, Ray A, Ray P. Activation of c-Kit in dendritic cells regulates T helper cell differentiation and allergic asthma. Nat Med. 2008;14(5):565–573. doi: 10.1038/nm1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitamura Y, Tsujimura T, Jippo T, Kasugai T, Kanakura Y. Regulation of development, survival and neoplastic growth of mast cells through the c-kit receptor. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;107(1-3):54–56. doi: 10.1159/000236929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galli SJ, Zsebo KM, Geissler EN. The kit ligand, stem cell factor. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:1–96. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda H, Kanakura Y, Tamaki T, Kuriu A, Kitayama H, Ishikawa J, Kanayama Y, Yonezawa T, Tarui S, Griffin JD. Expression and functional role of the proto-oncogene c-kit in acute myeloblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 1991;78(11):2962–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Curtis JE, Geissler EN, McCulloch EA, Minden MD. The expression of the proto-oncogene C-kit in the blast cells of acute myeloblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1989;3(10):699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahzouni P, Jafari M. The study of CD117 expression in glial tumors and its relationship with the tumor-type and grade. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(2):159–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montone KT, van Belle P, Elenitsas R, Elder DE. Proto-oncogene c-kit expression in malignant melanoma: protein loss with tumor progression. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(9):939–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natali PG, Nicotra MR, Winkler AB, Cavaliere R, Bigotti A, Ullrich A. Progression of human cutaneous melanoma is associated with loss of expression of c-kit proto-oncogene receptor. Int J Cancer. 1992;52(2):197–201. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hida T, Ueda R, Sekido Y, Hibi K, Matsuda R, Ariyoshi Y, Sugiura T, Takahashi T. Ectopic expression of c-kit in small-cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1994;8:108–109. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krystal GW, Hines SJ, Organ CP. Autocrine growth of small cell lung cancer mediated by coexpression of c-kit and stem cell factor. Cancer Res. 1996;56(2):370–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hines SJ, Organ C, Kornstein MJ, Krystal GW. Coexpression of the c-kit and stem cell factor genes in breast carcinomas. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6(6):769–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellone G, Carbone A, Sibona N, Bosco O, Tibaudi D, Smirne C, Martone T, Gramigni C, Camandona M, Emanuelli G, Rodeck U. Aberrant activation of c-kit protects colon carcinoma cells against apoptosis and enhances their invasive potential. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):2200–2206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catalano A, Rodilossi S, Rippo MR, Caprari P, Procopio A. Induction of stem cell factor/c-Kit/slug signal transduction in multidrug-resistant malignant mesothelioma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46706–46714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chau WK, Ip CK, Mak AS, Lai HC, Wong AS. c-Kit mediates chemoresistance and tumor-initiating capacity of ovarian cancer cells through activation of Wnt/beta-catenin-ATP-binding cassette G2 signaling. Oncogene. 2012;32(22):2767–2781. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duensing A, Medeiros F, McConarty B, Joseph NE, Panigrahy D, Singer S, Fletcher CD, Demetri GD, Fletcher JA. Mechanisms of oncogenic KIT signal transduction in primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) Oncogene. 2004;23(22):3999–4006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo L, Zeng J, Liang B, Zhao Z, Sun L, Cao D, Yang J, Shen K. Ovarian cancer cells with the CD117 phenotype are highly tumorigenic and are related to chemotherapy outcome. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91(2):596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinho O, Goncalves A, Moreira MA, Ribeiro LF, Queiroz GS, Schmitt FC, Reis RM, Longatto-Filho A. KIT activation in uterine cervix adenosquamous carcinomas by KIT/SCF autocrine/paracrine stimulation loops. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111(2):350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theou-Anton N, Tabone S, Brouty-Boye D, Saffroy R, Ronnstrand L, Lemoine A, Emile JF. Co expression of SCF and KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) suggests an autocrine/paracrine mechanism. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(8):1180–1185. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hibi K, Takahashi T, Sekido Y, Ueda R, Hida T, Ariyoshi Y, Takagi H. Coexpression of the stem cell factor and the c-kit genes in small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 1991;6(12):2291–2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellone G, Smirne C, Carbone A, Buffolino A, Scirelli T, Prati A, Solerio D, Pirisi M, Valente G, Nano M, Emanuelli G. KIT/stem cell factor expression in premalignant and malignant lesions of the colon mucosa in relationship to disease progression and outcomes. Int J Oncol. 2006;29(4):851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao XN, Lin J, Li YH, Gao L, Wang XR, Wang W, Kang HY, Yan GT, Wang LL, Yu L. MicroRNA-193a represses c-kit expression and functions as a methylation-silenced tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2011;30(31):3416–3428. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao XN, Lin J, Gao L, Li YH, Wang LL, Yu L. MicroRNA-193b regulates c-Kit proto-oncogene and represses cell proliferation in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2011;35(9):1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, Valtieri M, Calin GA, Liu CG, Sorrentino A, Croce CM, Peschle C. MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(50):18081–18086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506216102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim WK, Park M, Kim YK, Tae YK, Yang HK, Lee JM, Kim H. MicroRNA-494 downregulates KIT and inhibits gastrointestinal stromal tumor cell proliferation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(24):7584–7594. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391(6669):806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408(6810):307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbas HA, Pant V, Lozano G. The ups and downs of p53 regulation in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(19):3257–3262. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.19.17721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermeking H. MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(9):613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrc3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(2):193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boon RA, Iekushi K, Lechner S, Seeger T, Fischer A, Heydt S, Kaluza D, Treguer K, Carmona G, Bonauer A, Horrevoets AJ, Didier N, Girmatsion Z, Biliczki P, Ehrlich JR, Katus HA, et al. MicroRNA-34a regulates cardiac ageing and function. Nature. 2013;495(7439):107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siemens H, Jackstadt R, Hunten S, Kaller M, Menssen A, Gotz U, Hermeking H. miR-34 and SNAIL form a double-negative feedback loop to regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(24):4256–4271. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.24.18552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Rago C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Identification and classification of p53-regulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(25):14517–14522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalimutho M, Di Cecilia S, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Roviello F, Sileri P, Cretella M, Formosa A, Corso G, Marrelli D, Pallone F, Federici G, Bernardini S. Epigenetically silenced miR-34b/c as a novel faecal-based screening marker for colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(11):1770–1778. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogt M, Munding J, Gruner M, Liffers ST, Verdoodt B, Hauk J, Steinstraesser L, Tannapfel A, Hermeking H. Frequent concomitant inactivation of miR-34a and miR-34b/c by CpG methylation in colorectal, pancreatic, mammary, ovarian, urothelial, and renal cell carcinomas and soft tissue sarcomas. Virchows Arch. 2011;458(3):313–322. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-1030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toyota M, Suzuki H, Sasaki Y, Maruyama R, Imai K, Shinomura Y, Tokino T. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4123–4132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiesenauer CA, Yip-Schneider MT, Wang Y, Schmidt CM. Multiple anticancer effects of blocking MEK-ERK signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(3):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peparini N, Caronna R, Tellan G, Chirletti P. Expression of receptors tyrosine kinase c-kit and EGF-R in colorectal adenocarcinomas: is there a relationship with epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(6):1131–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0513-9. author reply 1133-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang Y, Liang X, Zheng M, Zhu Z, Zhu G, Yang J, Chen Y. Expression of c-kit and Slug correlates with invasion and metastasis of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(4):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasuda A, Sawai H, Takahashi H, Ochi N, Matsuo Y, Funahashi H, Sato M, Okada Y, Takeyama H, Manabe T. Stem cell factor/c-kit receptor signaling enhances the proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer cells through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(9):2292–2300. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9759-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kent D, Copley M, Benz C, Dykstra B, Bowie M, Eaves C. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cells by the steel factor/KIT signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(7):1926–1930. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoermann G, Cerny-Reiterer S, Perne A, Klauser M, Hoetzenecker K, Klein K, Mullauer L, Groger M, Nijman SM, Klepetko W, Valent P, Mayerhofer M. Identification of oncostatin M as a STAT5-dependent mediator of bone marrow remodeling in KIT D816V-positive systemic mastocytosis. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(5):2344–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lennartsson J, Blume-Jensen P, Hermanson M, Ponten E, Carlberg M, Ronnstrand L. Phosphorylation of Shc by Src family kinases is necessary for stem cell factor receptor/c-kit mediated activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and c-fos induction. Oncogene. 1999;18(40):5546–5553. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kemper K, Grandela C, Medema JP. Molecular identification and targeting of colorectal cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2010;1(6):387–395. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma Y, Liang D, Liu J, Axcrona K, Kvalheim G, Giercksky KE, Nesland JM, Suo Z. Synergistic effect of SCF and G-CSF on stem-like properties in prostate cancer cell lines. Tumour Biol. 2012;33(4):967–978. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0325-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, Espinoza LA, Kinders RJ, Lawrence SM, Pfister TD, Zhou M, Veenstra TD, Thorgeirsson SS, Jessup JM. NANOG modulates stemness in human colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.461. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horst D, Chen J, Morikawa T, Ogino S, Kirchner T, Shivdasani RA. Differential WNT activity in colorectal cancer confers limited tumorigenic potential and is regulated by MAPK signaling. Cancer Res. 2012;72(6):1547–1556. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wellner U, Schubert J, Burk UC, Schmalhofer O, Zhu F, Sonntag A, Waldvogel B, Vannier C, Darling D, zur Hausen A, Brunton VG, Morton J, Sansom O, Schuler J, Stemmler MP, Herzberger C, et al. The EMT-activator ZEB1 promotes tumorigenicity by repressing stemness-inhibiting microRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(12):1487–1495. doi: 10.1038/ncb1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muzny. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji Q, Hao X, Meng Y, Zhang M, Desano J, Fan D, Xu L. Restoration of tumor suppressor miR-34 inhibits human p53-mutant gastric cancer tumorspheres. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:266. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bellone G, Silvestri S, Artusio E, Tibaudi D, Turletti A, Geuna M, Giachino C, Valente G, Emanuelli G, Rodeck U. Growth stimulation of colorectal carcinoma cells via the c-kit receptor is inhibited by TGF-beta 1. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199707)172:1<1::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friederichs J, von Weyhern CW, Rosenberg R, Doll D, Busch R, Lordick F, Siewert JR, Sarbia M. Immunohistochemical detection of receptor tyrosine kinases c-kit, EGF-R, and PDGF-R in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395(4):373–379. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reed J, Ouban A, Schickor FK, Muraca P, Yeatman T, Coppola D. Immunohistochemical staining for c-Kit (CD117) is a rare event in human colorectal carcinoma. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2002;2(2):119–122. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2002.n.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yorke R, Chirala M, Younes M. c-kit proto-oncogene product is rarely detected in colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3885–3886. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.213. discussion 3886-3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El-Serafi MM, Bahnassy AA, Ali NM, Eid SM, Kamel MM, Abdel-Hamid NA, Zekri AR. The prognostic value of c-Kit, K-ras codon 12, and p53 codon 72 mutations in Egyptian patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(21):4954–4964. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sammarco I, Capurso G, Coppola L, Bonifazi AP, Cassetta S, Delle Fave G, Carrara A, Grassi GB, Rossi P, Sette C, Geremia R. Expression of the proto-oncogene c-KIT in normal and tumor tissues from colorectal carcinoma patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19(6):545–553. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Preto A, Moutinho C, Velho S, Oliveira C, Rebocho AP, Figueiredo J, Soares P, Lopes JM, Seruca R. A subset of colorectal carcinomas express c-KIT protein independently of BRAF and/or KRAS activation. Virchows Arch. 2007;450(6):619–626. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lahm H, Amstad P, Yilmaz A, Borbenyi Z, Wyniger J, Fischer JR, Suardet L, Givel JC, Odartchenko N. Interleukin 4 down-regulates expression of c-kit and autocrine stem cell factor in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6(9):1111–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Attoub S, Rivat C, Rodrigues S, Van Bocxlaer S, Bedin M, Bruyneel E, Louvet C, Kornprobst M, Andre T, Mareel M, Mester J, Gespach C. The c-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 for colorectal cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62(17):4879–4883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Oosterom AT, Judson I, Verweij J, Stroobants S, Donato di Paola E, Dimitrijevic S, Martens M, Webb A, Sciot R, Van Glabbeke M, Silberman S, Nielsen OS. Safety and efficacy of imatinib (STI571) in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a phase I study. Lancet. 2001;358(9291):1421–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06535-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bellone G, Ferrero D, Carbone A, De Quadros MR, Gramigni C, Prati A, Davidson W, Mioli P, Dughera L, Emanuelli G, Rodeck U. Inhibition of cell survival and invasive potential of colorectal carcinoma cells by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3(4):385–392. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujita Y, Kojima K, Hamada N, Ohhashi R, Akao Y, Nozawa Y, Deguchi T, Ito M. Effects of miR-34a on cell growth and chemoresistance in prostate cancer PC3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377(1):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim CH, Kim HK, Rettig RL, Kim J, Lee ET, Aprelikova O, Choi IJ, Munroe DJ, Green JE. miRNA signature associated with outcome of gastric cancer patients following chemotherapy. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li XJ, Ji MH, Zhong SL, Zha QB, Xu JJ, Zhao JH, Tang JH. MicroRNA-34a Modulates Chemosensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells to Adriamycin by Targeting Notch1. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(7):514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang X, Dong K, Gao P, Long M, Lin F, Weng Y, Ouyang Y, Ren J, Zhang H. microRNA-34a Sensitizes Lung Cancer Cell Lines to DDP Treatment Independent of p53 Status. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2012;28(1):45–50. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bader AG. miR-34 -a microRNA replacement therapy is headed to the clinic. Front Genet. 2012;3:120. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsu HC, Liu YS, Tseng KC, Hsu CL, Liang Y, Yang TS, Chen JS, Tang RP, Chen SJ, Chen HC. Overexpression of Lgr5 correlates with resistance to 5-FU-based chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1721-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bitarte N, Bandres E, Boni V, Zarate R, Rodriguez J, Gonzalez-Huarriz M, Lopez I, Javier Sola J, Alonso MM, Fortes P, Garcia-Foncillas J. MicroRNA-451 is involved in the self-renewal, tumorigenicity, and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29(11):1661–1671. doi: 10.1002/stem.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, Evangelista M, Citti L, Woods K, Mercatanti A, Hammond S, Rainaldi G. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood. 2006;108(9):3068–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, Gong C, Huang Y, Hu X, Su F, Lieberman J, Song E. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131(6):1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garofalo M, Jeon YJ, Nuovo GJ, Middleton J, Secchiero P, Joshi P, Alder H, Nazaryan N, Di Leva G, Romano G, Crawford M, Nana-Sinkam P, Croce CM. MiR-34a/c-Dependent PDGFR-alpha/beta Downregulation Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Enhances TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis in Lung Cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shin J, Pan H, Zhong XP. Regulation of mast cell survival and function by tuberous sclerosis complex 1. Blood. 2012;119(14):3306–3314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-353342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang P, Li QJ, Feng Y, Zhang Y, Markowitz GJ, Ning S, Deng Y, Zhao J, Jiang S, Yuan Y, Wang HY, Cheng SQ, Xie D, Wang XF. TGF-beta-miR-34a-CCL22 signaling-induced Treg cell recruitment promotes venous metastases of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(3):291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guntur VP, Reinero CR. The potential use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in severe asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(1):68–75. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834ecb4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jensen BM, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Targeting kit activation: a potential therapeutic approach in the treatment of allergic inflammation. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007;6(1):57–62. doi: 10.2174/187152807780077255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reber L, Da Silva CA, Frossard N. Stem cell factor and its receptor c-Kit as targets for inflammatory diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533(1-3):327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guo Y, Li S, Qu J, Wang S, Dang Y, Fan J, Yu S, Zhang J. MiR-34a inhibits lymphatic metastasis potential of mouse hepatoma cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;354(1-2):275–282. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu C, Kelnar K, Liu B, Chen X, Calhoun-Davis T, Li H, Patrawala L, Yan H, Jeter C, Honorio S, Wiggins JF, Bader AG, Fagin R, Brown D, Tang DG. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat Med. 2011;17(2):211–215. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pramanik D, Campbell NR, Karikari C, Chivukula R, Kent OA, Mendell JT, Maitra A. Restitution of tumor suppressor microRNAs using a systemic nanovector inhibits pancreatic cancer growth in mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(8):1470–1480. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wiggins JF, Ruffino L, Kelnar K, Omotola M, Patrawala L, Brown D, Bader AG. Development of a lung cancer therapeutic based on the tumor suppressor microRNA-34. Cancer Res. 2010;70(14):5923–5930. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kasinski AL, Slack FJ. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):849–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jackstadt R, Roh S, Neumann J, Jung P, Hoffmann R, Horst D, Berens C, Bornkamm GW, Kirchner T, Menssen A, Hermeking H. AP4 is a mediator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Exp Med. 2013;210(7):1331–1350. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(5):330–338. doi: 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Di Marco A, Gaetani M, Scarpinato B. Adriamycin (NSC-123,127): a new antibiotic with antitumor activity. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1969;53(1):33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Welch C, Chen Y, Stallings RL. MicroRNA-34a functions as a potential tumor suppressor by inducing apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(34):5017–5022. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2010;17(2):193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Siemens H, Neumann J, Jackstadt R, Horst D, Kirchner T, Hermeking H. Detection of miR-34a promoter methylation in combination with elevated expression of Snail, c-Met and b-catenin predicts distant metastasis of colon cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013;19(3):710–720. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kaller M, Liffers ST, Oeljeklaus S, Kuhlmann K, Röh S, Hoffmann R, Warscheid B, Hermeking H. Genome-wide characterization of miR-34a induced changes in protein and mRNA expression by a combined pulsed SILAC and micro-array analysis. Molecular Cellular Proteomics. 2011;10(8):1–16. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010462. M111.010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hermeking H. p53 enters the microRNA world. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(5):414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.