Abstract

Many authors have pointed out the need for simpler assessment and management procedures for avoiding overexploitation in small-scale fisheries. Nevertheless, models for providing scientific advice for sustainable small-scale fisheries management have not yet been published. Here we present one model; the case of the Barefoot Fisheries Advisors (BFAs) in the Galician co-managed Territorial Users Rights for Fishing. Based on informal interviews, gray literature and our personal experience by being involved in this process, we have analyzed the historical development and evolution of roles of this novel and stimulating actor in small-scale fisheries management. The Galician BFA model allows the provision of good quality and organized fisheries data to facilitate and support decision-making processes. The BFAs also build robust social capital by acting as knowledge collectors and translators between fishers, managers, and scientists. The BFAs have become key actors in the small-scale fisheries management of Galicia and a case for learning lessons.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-013-0460-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Barefoot Fisheries Advisors, Small-scale fisheries, Co-management systems, S-fisheries, Scientific advice, Knowledge collectors and translators

Introduction

The overexploitation of the world’s main commercial fisheries has been well documented (FAO 2012). This is undoubtedly the result of rapid technological development of fishing fleets (Villasante and Sumaila 2010), which lead to an increasing number of overexploited and collapsed fish stocks over time (Worm et al. 2009) and a reduction of marine ecosystem services (Carpenter et al. 2009). Most scientific studies have been focused on the analysis of industrial fisheries, with little attention to small-scale fisheries. However, in a global study to assess the status of small-scale fisheries, which are mostly unassessed, Costello et al. (2012) found that small unassessed fisheries are in substantially worse condition than assessed fisheries.

Much of the current work on finding solutions in areas like harvest policies, decision rules, and their evaluation focuses on relatively large-scale and geographically extensive fisheries. Moreover, the use of biomass or fishing intensity indices are usually estimated using sophisticated stock assessment models hungry of data (Sainsbury et al. 2000; Punt et al. 2001). Therefore, many of the conceived approaches found to address overfishing require many data and complex model structures. This is beyond the capability of most fisheries in terms of economic costs and human and technological resources (Walters and Pearse 1996; Cochrane 1999), especially for small-scale fisheries in both developing and developed countries (Wilson et al. 2010). Many authors have pointed out the need for simpler assessment and management procedures, in which fishers are actively involved, based on indicators collected directly from the catch and/or from simple surveys (Johannes 1998; Berkes et al. 2001; Hilborn 2003; Orensanz et al. 2005; Ostrom 2007; Prince 2010).

Prince (2003, 2010) has proposed that Barefoot ecologists can play a key role in those procedures by not only affordably collecting and analyzing reliable and precise information on status and trends of local resources, but also by having a wider role in building social capital and strengthening fishing community structures. Moreover, on-site fishery workers like the Barefoot ecologists could allow evolution from primary management (i.e., avoiding undesirable thresholds and focused on social and ecological resilience) to tertiary management (i.e., seeking well informed and adaptive management that strives for optimal benefits) in the framework proposed by Cochrane et al. (2011) for co-managed small-scale fisheries. There is therefore a need to describe new decentralized models/figures for providing scientific/technical support for the sustainable co-management of small-scale fisheries that captures both the natural and human dimensions of the fisheries.

The aim of this paper is to navigate through the management system of the artisanal shellfisheries in Galicia (NW Spain), one of the most important fishing areas in Europe from a natural and socioeconomic perspective. The objective of this paper is to focus on the historical development of a novel figure in small-scale fisheries management called Technical Assistants in Shellfisheries Management1 (hereinafter TAs). As on-site Barefoot Fisheries Advisors (BFAs) of the fisher’s guilds (cofradías), we analyze their roles ranging from biological assessment of fishery resources, data collection, and development of new and innovative projects covering ecological, economic, and institutional dimensions of a given fishery. We also consider weak points and future perspectives.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

Galicia is an autonomous Spanish region with full authority over the management of its coastal fisheries along its 1200 km of coastline. Fishing powers were transferred to Galicia from the Spanish Government by the Galician Statute of Autonomy in 1981, but only for shellfisheries and the rest of the fisheries taking place in the inner coastal waters between the coastline and an imaginary line along the exterior of the outer islands, rocky islets, and capes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of Galicia with the base line (red line) which marks out the limit of the Galician coastal waters (Decreto no. 2510/77, BOE no. 234). Fisheries management in coastal waters is competency of the Galician government (Xunta de Galicia) thought the Fisheries Administration (Consellería do Medio Rural e do Mar). From the red line to 12 miles is Spanish authority

The relevance of fishing in Galicia as an economic activity and from a social–ecological perspective is higher than compared to the rest of Spain or other EU regions. In the Spanish fisheries sector, Galicia represents around 43 % of the number of vessels, more than 34 % of the fleet capacity, and nearly 40 % of the number of jobs (Villasante 2012). The activity strongly contributes added value to the gross domestic product in Galicia. In fact, the percentage of Gross Value Added of fisheries and aquaculture compared to the Gross Domestic Product is 2.4 % in Galicia, while only 0.2 % in EU-27 (Villasante 2012; Consellería do Medio Rural e do Mar 2013).

In Galicia around 15 000 fishers in the coastal waters sold (aquaculture excluded) 175 000 ton to the value of EUR 440.5 million in 2012. Although the majority (86 % in volume and 75 % in value) of the landings corresponded to fish, shellfish activity is still very relevant; 23 610 ton (EUR 111 million) were fished shared between ~60 species (cephalopods, bivalves, crustaceans, gastropods, equinoderms, annelids, sea anemones, and algae) (Consellería do Medio Rural e do Mar 2013).

The fishing activity in Galicia has a strong secular tradition as well as its organization. Fishers were organized since the Middle Ages in local fishers’ guilds (cofradías), which were economic associations under religious bases (Franquesa 2004; Taboada 2007). The cofradías allowed, since then, some forms of co-governance in fisheries, since they were institutions of public right that held the role of managing some of the fisheries activities developed in the areas under their jurisdiction (Frangoudes et al. 2008). Nevertheless, in Galicia, historically the shellfishing has been mostly carried out, until the 1990s, as a de facto open access system (Lopez Veiga et al. 1992; Frangoudes et al. 2008).

During the 1960s–1980s, coinciding with the increasing number of shellfishers, market demand, and economic value of the shellfish, the fisheries administration introduced step-by-step new regulations to rationalize and manage the activity. But, it was not until 1992 when the Galician government, with fishing powers since 1981, introduced the biggest change; a new model for shellfishing, promoting a co-management system between cofradías and the fisheries administration,2 based on territorial use rights for fishing (TURFs) over a large area and its resources (Molares and Freire 2003). The new management system, still ongoing, is only applied to sedentary resources (bivalves, echinoderms, gastropods, annelids, algae, and gooseneck barnacles), concerning therefore the so-called S-fisheries (Small-Scale and Spatially Structured fisheries targeting Sedentary resources with artisanal gears, sensu Orensanz et al. 2005). Galician S-fisheries involve ~3500 on boat fishers and ~5000 afoot fishers (mostly women) (Consellería do Medio Rural e do Mar 2013). The main tool of the new system is the Exploitation and Management Plan (Plans de Explotación), which specifies annually the different components of the management system: authorized fishers, fishing grounds, general objectives, state of the fishery and stock assessment analyses, harvesting and trade plans, actions for stock enhancement, and a financial plan (see Box 1 for details).

Box 1.

S-fisheries Exploitation and Management Plans

| General data |

| Number and nominal list of fishers (and cofradías involved if joint plans) |

| Number of boats and nominal relation of crews |

| Resources to be exploited (plans are commonly multi-specific) |

| Harvest grounds (general map and detailed limits) |

| General objectives |

| Production objectives (year total catch) |

| Economic objectives (total and per capita yearly incomes) |

| State of the fishery and stock assessment analysis |

| Historical data of the fishery (catch, effort, CPUE, sizes, sales price, etc.) |

| Methods used and results obtained in the assessments |

| Results obtained in the sizes controls (in situ and in the first-sale market) |

| Conclusions and recommendations |

| Implementation of methods to control the exploitation |

| Daily effort (number of fishers and boats), catches and sales |

| Surveillance method to control effort, catches and sizes |

| Check points (close to fishing grounds) |

| Harvesting and trade plans |

| Foreseeable calendar (including close season if required) |

| Total number of fishing days |

| Maximum fisher/boat daily quotas |

| Daily harvest grounds planned and gears used |

| Control points and surveillance |

| Sales strategy (auction, direct sale, internet, etc.) |

| Sales agreements (first-sale markets, minimum prices, etc.) |

| Actions for stock enhancement |

| Description of the action |

| Materials and methods |

| Costs |

| Actions for improving the fishery |

| Description of the improvement |

| Projects running (description, institutions involved, objectives, results, etc.) |

| Financial plan |

| Incomes and expenses |

| Investment |

| Capitalization |

Information that the cofradías have to include in the S-fisheries Exploitation and Management Plan to fulfill the fisheries administration requirements (CPUE stands for captures per unit effort) (source modified from Molares and Freire 2003)

Data Collection and Information

Data on the number of TAs since the beginning of the program in 1993 were gathered through a brief questionnaire (by email, phone call, or personal meeting) to all TAs in Galicia. The recollection started in July 2010 and data were updated in August 2013. Since many TAs were new in the cofradías, older members (administratives, managers, head of the cofradías, ex-TAs, etc.) were also contacted mostly for clarifying the situation in the 1990s. The rest of the cofradías that do not have hired TAs were also contacted for verification.

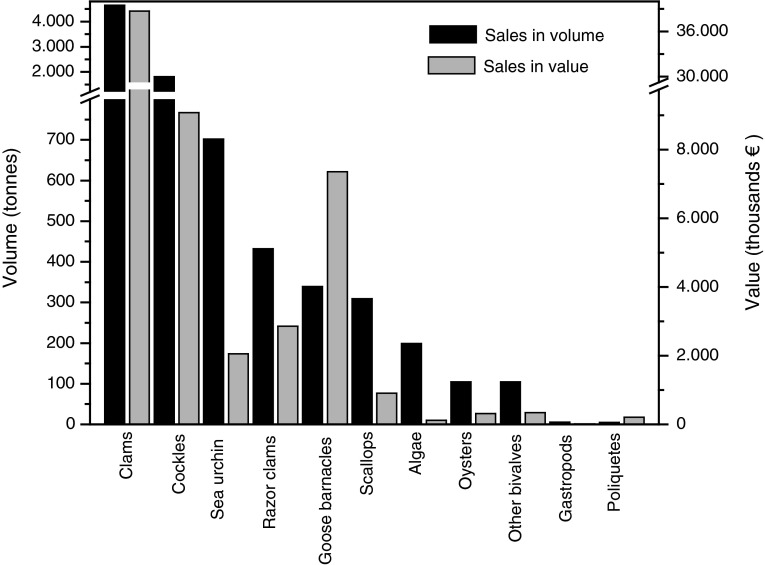

Data on 2012 official fresh resources’ sales (in volume and value) in the Galician first auctions were downloaded from the fisheries administration database (available at the web site www.pescadegalicia.com). All first auctions and markets in Galicia were included in this search. Data on the S-fisheries resources were downloaded grouped in the following categories: clams (7 species), cockles (2), razor clams (3), scallops (3), oysters (2), other bivalves (7), sea urchins (1), crustaceans (1), gastropods (4), annelids (4), sea anemones (1), and seaweeds (10) (for a list of the species included in each group, see Electronic Supplementary Material).

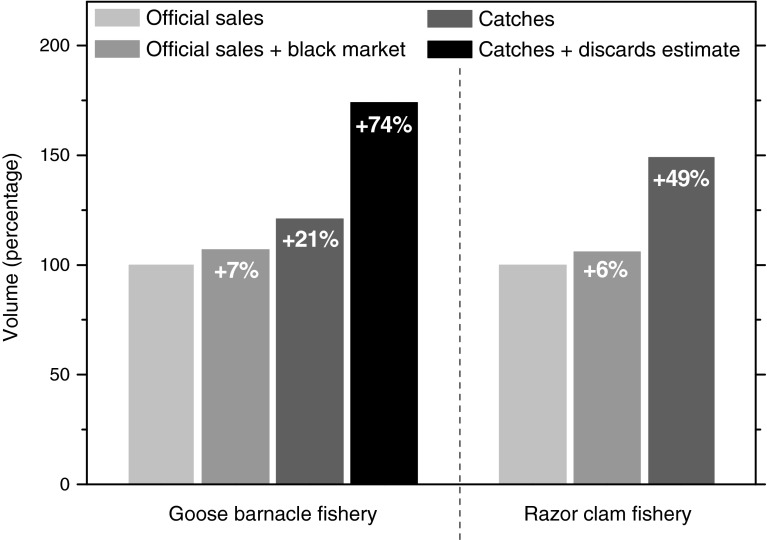

Data on catches and black market sales for goose barnacle (Pollicipes pollicipes) and razor clam (Ensis arcuatus) fisheries were kindly provided by two TAs of two different cofradías. An estimation of discards for the goose barnacle fishery was also provided by a TA. For guaranteeing anonymity, neither the names of the cofradías nor the year when the data came from are provided in this work. These unofficial data were compared with the official sales available at www.pescadegalicia.com.

For compiling the information required in the Exploitation and Management Plans, we followed Molares and Freire (2003) as an initial reference but also many official plans from 2010 to 2013 from different cofradías were checked modifying the final table and the information included.

The list of roles and duties and the historic development of the Galician BFAs plan was compiled from July 2010 to August 2013 by informal meetings, queries, and interviews with all present Galician TAs and several ex-TAs, and also by consulting the gray literature and the Galician official gazette. Managers, biologists, and other staff from the fisheries administration were also consulted. Finally, our own experiences after more than 20 years directly involved in different aspects of the Galician fisheries management were used.

Results

The Key Role of the Barefoot Fisheries Advisors in Transforming Galician S-fisheries

Despite the strong shellfishing tradition in Galicia and its socioeconomic relevance, the technical advice of the fisheries administration, just like the scientific advice from universities and research institutions, was weak before the 1990s. This was the result of an historic non-collaborative environment between Galician fishers, managers, and scientists and lack of political support (Freire 2000). Technical advice was given by a small group of biology graduates and extension workers from the fisheries administration, which by far was insufficient for the huge amount of shellfisheries and fisher groups. The marine research center Centro de Investigacións Mariñas (CIMA), the official institution belonging to the fisheries administration and responsible for giving scientific advice to shellfisheries was small, while other state research institutions and universities were almost not implicated in any way. Ricardo Arnáiz, in charge of the Galician Technical Unit for Small-Scale Fisheries,3 described in 2001 the consequences of this situation as:

gaps of knowledge in artisanal or small-scale fisheries, concerning target species, fishing gears and their effect on the environment, are of astonishing extent (Arnáiz 2001).

During the middle of the 1990s, the fisheries administration started a plan oriented to make a shift in the shellfishing sector, from unorganized shellfishers unsustainably gathering wild resources to organized shellfishers groups that do not only gather sustainably, but also increase productivity by seeding and mariculture. The plan hired several young biologists and/or aquaculture technicians who worked in strong collaboration with the biologists from the fisheries administration (hereinafter FA biologists) and the fishers in bivalve enhancing techniques and mariculture. That group of people was the embryo of the current TAs program, trough which the TAs have developed their roles and responsibilities, not only concerning bivalve mariculture, but getting involved in the whole S-fisheries management system as a key actor in the Galician model.

Historic Evolution of the Asistencias Técnicas Program

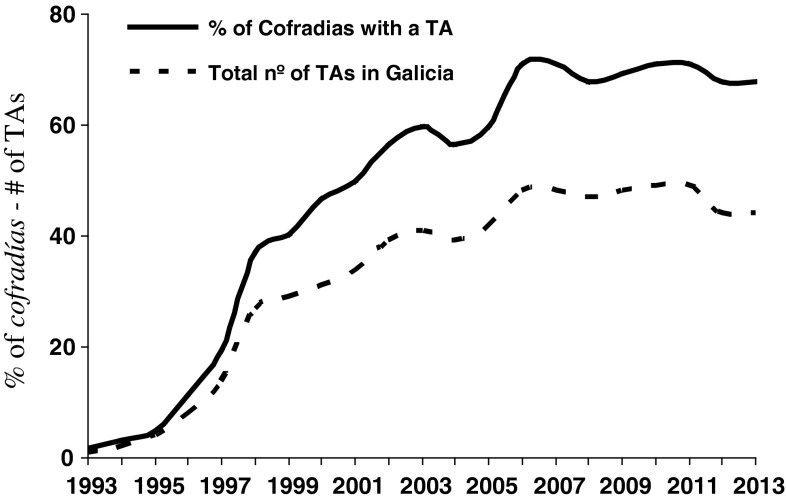

The TAs program was born in Galicia in 1993. From a bivalve seeding and mariculture pilot project (1993–1995) for two women shellfisher groups, the program quickly evolved into a large plan for managing all S-fisheries of almost all Galician cofradías (see Table 1 for the historical development of the TAs program and Fig. 2 for the number of TAs and cofradías involved along years). We have divided this evolution into three phases: First, technical advice to the artisanal fisheries before the 1990s; second, why and how the TAs program was born and the way it was scaled-up into bigger plans; and third (from 2000s to now), strengthening of the program and the new impulse that took place.

Table 1.

Historical development of the Asistencias Técnicas (TAs) program in Galicia. [Years years when the plan took place, plan name of the plan, institution institution that hires the TAs, office where is the TA’s office, TAs number of TAs hired, cofradías number and percentage (between brackets) of cofradías participating in this plan, resources resources that are responsibility of the TA, TA roles main roles and duties of the TAs during the plan] (FA stands for fisheries administration, E&MP stand for Exploitation and Management Plan)

| Years | Plan | Institution | Office | TAs | Cofradías b | Resources | TAs roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993–1995 | CIMA’s project | CIMAa | CIMA | 2 | 2 (3 %) | Grooved carpet shell clam and flat oyster | Seeding and intertidal mariculture |

| 1996 | Plan 10 | Galician FA | Galician FA offices | 8 | 9 (13 %) | Clams and oysters | Seeding and intertidal mariculture |

| 1997–1999 | Plan Galicia | Galician FA | Begin: Galician FA offices End: cofradías |

From 14, to 31 | From 15 (21 %) to 33 (47 %) | Clams and oysters + some S-fisheries | Seeding and intertidal mariculture + E&MP |

| 2000–2006 | Collaborative agreement | Cofradías | Cofradías | From 34, to 48 | From 36 (51 %) to 51 (73 %) | S-fisheries resources | Many (see Box 2) |

| 2007–2009 | Project | Cofradías | Cofradías | 48 | 51 (73 %) | S-fisheries resources | Many (see Box 2) |

| 2010–2012 | Collaborative agreement | Cofradías | Cofradías | From 49, to 44 | From 52 (74 %) to 47 (67 %) | S-fisheries resources | Many (see Box 2) |

| 2013 | Project | Cofradías | Cofradías | 44 | 47 (67 %) | S-fisheries resources | Many (see Box 2) |

aAlthough different institutions hired the TAs at different times, the funds always came from the Galician government using own resources and European Fisheries Funds

bBy cofradías are also included shellfisher’s groups, shellfisher’s associations, cooperatives and a producing organization, since these other organizations are also granted with funds from the fisheries administration for hiring a TA)

Fig. 2.

Development from 1993 to present of the TAs program in Galicia (solid line percentage of cofradías with a TA, dashed line total number of TAs) (source: own compilation from interviews with TAs)

The Previous Situation (Before the 1990s)

First attempts to professionalize and give technical advice to the Galician artisanal fisheries took place in 1969 under the framework of the Law of Shellfishing Planning and the Decree for Shellfishing Exploitation Plan of Galicia4 (Mahou 2008). Economic and technical support was implemented to prepare the shellfishers mentally to shift from gatherers to harvesters, with the main objective of raising the living standards of shellfishers. It was a well-intentioned plan but it failed due to legislative, organizational, and enforcement problems (González-Vidal 1980), the ignorance of the shellfishing sector, the attempt to impose imported solutions, and the lack of democracy in the fisheries management (Mahou 2008). However, it did establish the first TAs and extension workers, as the technical and human base for the upcoming regional Fishery Authority, when the fishing powers were transferred to Galicia in 1981 (Mahou 2008).

During the 1980s, the regional authorities tried to reinforce the previous rules by introducing several regulations that refined the requisites for shellfishing (Frangoudes et al. 2008), ending up with the first fishing law dictated by the regional government, the Galician Law 9/1993 (Lei 6/1993 de Pesca de Galicia). At the same time the fisheries administration continued reinforcing the group of biologists and extension workers and their role, although its development was still weak.

The Pilot Project and the Subsequent Scaled-Up Plans (from 1993 to 1999)

In 1993, the CIMA (the marine research center from the fisheries administration) lead a 3-year long pilot project focused on enhancing techniques (seeding and predator removal) and intertidal mariculture of the grooved carpet shell (Ruditapes decussatus) and the common oyster (Ostrea edulis). The shellfishing beds of two agrupacións de mariscadoras (women shellfisher groups that belong to the cofradías) were selected for their closeness to the CIMA. The novelty of this project was that two biology graduates were hired as TAs to work closely and exclusively with two agrupacións de mariscadoras. Intertidal shellfish gathering in Galicia is an activity that has traditionally been developed mainly by women, nowadays in a co-governance scheme with a type of license system (Frangoudes et al. 2008). The experience was very positive from a social–ecological point of view since the daily work together between mariscadoras and TAs created a new collaborative environment. Based on this by the end of the pilot project, in 1995, the fisheries administration launched the Plan 10.5

In 1996, Plan 10 was implemented and eight TAs (biologists and aquaculture technicians) were hired to work on seeding and mariculture initiatives on the intertidal clam beds of eleven cofradías (although the agreements were signed by the cofradías, the focus of the plan was still the mariscadoras, because the great majority of the afoot shellfishers in Galicia were women and, at that time they already had some degree of organization—Frangoudes et al. 2008). The main objectives of the plan were: (1) increase the productivity, (2) the gradual professionalization of the mariscadoras as a way to increase their incomes, and (3) the empowerment of the mariscadoras to get financial and technical autonomy and self-management capacity of their resources.

Plan 10 was scaled-up again to 33 cofradías (all the ones that in that time showed interest after an information campaign) resulting in the Plan Galicia6 (1997–1999), a key element of the Galician shellfisheries development. The plan was implemented following the same objectives and methodology as its precursor, with the novelty that since 1998 one of the requirements for the cofradías was to provide the TA with a place to work inside their facilities. This way the TAs, although directly hired by the fisheries administration and coordinated by the FA biologists, were physically assigned to the cofradías (Mahou 2008). That was a key point to increase knowledge sharing and trust between TAs and mariscadoras. During this period and because of this proximity, the TAs started helping in the design of the Exploitation and Management Plan for the cofradías, required since 1992 although gradually enforced during the forthcoming years (Molares and Freire 2003; Frangoudes et al. 2008). The Exploitation and Management Plans were not only required for clams and oysters fisheries, but for all S-fisheries (see Electronic Supplementary Material), so the TAs had to prepare many new plans. At the end of 1999, several meetings took place for analyzing the results; the mariscadoras showed their worry about the near future of the TAs after the plan finished, agreeing with the FA biologists and extension workers who considered very important to maintain the funds for hiring TAs in the future (Mahou 2008).

The Strengthening Phase (from 2000 to Now)

The fisheries administration realized that to consolidate the progress the investment in the TAs program had to be maintained after 1999, and promoted collaborative agreements with the cofradías. Between 2000 and 2006, 51 cofradías signed collaborative agreements with the fisheries administration (eight agreements were directly signed with shellfisher groups, shellfisher associations, cooperatives, and/or producing organizations, so hereinafter we will include these other institutions when referring to cofradías) to hire 48 TAs. For the first time, the TAs were not hired by the fisheries administration; this responsibility was transferred (funds as well) to the cofradías, to increase the liaison between them and the TAs.

From 2007 to 2009, the system changed and the cofradías applied for projects (it was not a competition just a formality) for getting funds for hiring TAs, although in practice nothing changed. Despite several shifts between collaborative agreements and projects, the number of cofradías and TAs in the program has been kept stable since 2006 (48 TAs for 51 cofradías), given that almost all the cofradías with S-fisheries were already taking part in the program. In 2011, 49 TAs were working in 52 cofradías (71 % of the cofradías) giving advice and support to 92 % of the Exploitation and Management Plans,7 the main management tool for the S-fisheries (see Fig. 3 for all S-fisheries sales supported by TAs).

Fig. 3.

Size and value of the S-fisheries in 2012 managed through a TA. (For a list of the species included in each group, see the Electronic Supplementary Material)

New Contributions of the Asistencias Técnicas

During the decade of 2000s, a great leap forward took place in the roles and duties of the TAs (see Box 2), mostly because of the fisheries administration requirements for the Exploitation and Management Plans and the direct relationship established between cofradías and TAs (several TAs pers. comm.).

Box 2.

Roles and duties of the BFAs

| State of the S-fisheries |

| *E&MP draw up and daily implementation |

| *Monthly reports on fisheries indicators (effort, catches, CPUEs, fishing areas, sales, etc.) |

| *Direct and in situ stock assessment every 6 months |

| *Frequently in situ samples on population size structure |

| Monthly/weekly samples on legal sizes at first-sale market |

| *Reports on fisheries status |

| Surveys for new shellfish beds and new resources |

| Organization of the surveillance data gathering at checking point |

| Biology and ecology works (reproduction, growth, recruitment, etc.) |

| Stock enhancement actions |

| *Apply for clams seeding projects |

| Coordinate fitting works (predators and algal removal, sediment conditioning, restocking, etc. |

| Sanitary monitoring of shellfish beds |

| *Collect samples for microbiology and biotoxin monitoring to INTECMAR |

| Report of dumping points |

| Special works (Prestige oil spill crisis, etc.) |

| Paperwork |

| E&MP daily management requests |

| Sampling, seeding and restocking requests |

| Organize fisher’s training courses (harvesting, diving, safety, etc.) |

| Draw up of surveillance plans |

| Advice to the cofradías and shellfishers groups |

| *General advice to the cofradías and shellfishers groups for sustainable management |

| Organize meetings (state of the fishery, E&MP, surveillance, conflicts, etc.) |

| Projects development for improving fisheries (in collaboration with research institutions) |

| Stock assessment and state of the fishery analysis |

| Hatcheries and mariculture |

| Marketing strategies and shellfish processing |

| Quality, origin and sustainable fisheries certifications |

| Sanitary and quality certifications of the first-sale market |

| Environmental issues (pollution, energy saving, renewable energies, etc.) |

| Other first-sale market works |

| Collaboration with surveillance in checkpoints |

| Auction responsibilities, sales tickets, loading, etc. |

| *Any other administration requirement concerning fisheries management |

Not all BFAs do all duties listed (* indicates compulsory duty to be reported to the administration, INTECMAR stands for Instituto Tecnolóxico do Mar, E&MP stands for Exploitation and Management Plan, CPUE stands for captures per unit effort) (source: own production based on TAs pers. comm. and authors experience)

To prepare the Exploitation and Management Plans, the TAs had to gather and organize the fisheries data, evaluate the state of the fishery and assess the stocks, while continuing with the stock enhancement actions and advice to the cofradías and shellfishers groups. Other tasks that the TAs took charge of were the paperwork associated with the new responsibilities and the dialog with the fisheries administration and fishers for the daily management of the fisheries. Another new responsibility is collecting samples for sanitary monitoring of water quality and shellfish beds and sending them to the Instituto Tecnolóxico para o Control do Medio Mariño (INTECMAR) a Galician fisheries administration center for marine environment quality control.

One of the main contributions of the TAs to the shellfisheries management in Galicia is the improvement in the quality of the fisheries data. Before the TAs program, the only available data were the sales data reported by each auction market to the fisheries administration, but when the TAs assumed the role of gathering this data, several of them implemented logbook programs with the fishers and digitalized the information of the catches collected by the local surveillance services (marine guards directly hired by the cofradías but co-paid between fishers/cofradía and the fisheries administration) available in many S-fisheries (157 local guards in Galicia in 2010 shared between ~60 cofradías). Catch data series are now available, including information not reported in the official landings, as catches that go to the black market and/or sometimes even discards (Fig. 4). Moreover, catches are also now spatially allocated to the fishing beds where they have been harvested (sometimes even a higher spatial resolution is given) allowing a spatial management like the implementation of rotational schedules in the harvesting.

Fig. 4.

Differences between the official sales statistics (from www.pescadegalicia.com), the known black market (main part of the black market is unknown) and the real catches from two cofradías (names not revealed) for a goose barnacle fishery (including an estimation of discards) and a razor clam fishery. For guaranteeing anonymity, the volume (in tonnes) is referred in percentage, using the official sales as baseline (100 %). The increase in percentage in relation to the official sales is also indicated. (Note: unofficial data were collected/estimated by TAs)

Development of innovative projects in collaboration with local research institutions was one of the new roles the TAs took in charge during 2000s. It was not a compulsory task required by the fisheries administration, but soon became a very powerful tool for developing improvements in the fisheries. Many projects in several fields (see Box 2) such as state of the fishery analysis or marketing strategies were implemented, and not only for S-fisheries but for any fishery related to the cofradía. This was allowed by governmental funds and the new impulse of young and motivated TAs for attending to cofradías and fishers’ concerns. This new role has become very important, not only for the results of the projects by themselves, but also because it has helped to strengthen the weak relationship between fishers, managers, and scientists that has historically existed in Galicia (Freire 2000). Two of these projects allowed, for example, getting the Marine Stewardship Council certification of sustainability, for the first time in Spain, for the razor clam fishery of the Cofradía de Bueu, or the creation of a fishers’ run business (Mar de Silleiro—http://www.mardesilleiro.com/) for selling delicatessens from gooseneck barnacle discards.

In 2007, the cofradías were officially required, for the first time, to fulfill a compulsory list of tasks (see Box 2) for getting funds for hiring TAs, although in general the TAs were already developing all those tasks. It was a way for the fisheries administration of maintaining the control over the responsibilities of the TAs, while continuing to develop the co-governance scheme between the cofradías and the fisheries administration. TAs continued developing their roles and duties, but not new compulsory tasks were added after 2007.

The Technical Support and Advice to the TAs

During the initial years, the advice to the TAs from the fisheries administration and the research centers was weak. There was almost no training or workshops, neither in the biological aspects of the fishery nor in the social ones and there were not sampling protocols or guidance on how to statically analyze the data collected from the fishery. The only support was from the FA biologists and sporadically from the CIMA for attending special circumstances like big mortalities associated to parasites or fresh water run-offs. Unfortunately the rest of the research centers and universities were not involved, because of their own lack of implication and the wrong sense of self-reliance from the fisheries administration. Moreover, the advice given was not well organized and there was a lack of coordination between biologists in charge and working protocols and therefore between TAs (TAs pers. comm.). As a result a diversity of techniques and methodologies was used to carry out the assessments, a heterogeneity that made it difficult to compare the results between areas and years (Parada and Molares 2012).

During the 2000s, several initiatives were launched to assess the fisheries from researchers from the CIMA who developed two platforms (SIGREMAR and AROUSA) and gave training to the TAs, and also to the FA biologists, which has significantly improved the level and quality of the fisheries data and its organization in common databases. SIGREMAR (http://ww3.intecmar.org/Sigremar/) started in 2000 as a geographic information system (GIS) designed for elaborating and controlling the S-fisheries management plans using a combination of the available statistical data and computer-based methods (Molares and Freire 2003). Although with some initial success, its complexity caused low implementation of several TAs and FA biologists who argued it was too time consuming and it was gradually abandoned (FA biologists and TAs pers. comm.). Nevertheless, SIGREMAR is still a powerful tool for spatially visualizing information of fishing beds. AROUSA (https://sites.google.com/site/arousa09asp/) is a Visual Basic application for Excel in use by the TAs since 2009, which aims to facilitate the use of standardized procedures for the stocks evaluation and technical advice on the exploitation and conservation of Galician shellfish resources. The stock assessment tools facilitate the calculation for several sampling techniques and are specially designed for stocks and population dynamics of benthic species. Other tools are implemented in the software, like length-weight ratios, mortality rates, evolution of the size structure of the population and control of catch size, among other features (Parada and Molares 2012).

Both platforms are freeware and assistance was given to the cofradías and FA biologists for using it; several workshops and training were done, especially for AROUSA during 2009–2012 and backup support was offered by the software developer (JM Parada) for solving bugs and implementing new useful tools demanded by users. Most of the TAs and FA biologists assisted to this training and AROUSA soon became a commonly used and essential tool for annually evaluating the status of several benthic resources.

The promotion from the fisheries administration since 2000s of innovative projects in the fishing sector has strongly helped to strengthen the relationship between TAs and the scientific community of the Galician universities and other research/monitoring institutions (IEO, CSIC, CETMAR, CIMA, and INTECMAR). Trough these projects, today the scientific community support the TAs in many fields (marketing certifications, population dynamics, fishery indicators, pathology issues, mariculture techniques, etc.). This collaboration has become a common source of advice and bidirectional learning.

Discussion

Along the past 20 years, the Galician BFAs have became a reference inside the cofradías and a person to contact for many stakeholders. By being inserted in the cofradía on a daily basis and by supporting and defending the fishers’ interests, the BFAs have created a trustful environment with the fishers, but also with the FA biologists, managers, and scientists, linking all of them and building social capital. Sato et al. (2013) in their conceived framework of Integrated Local Environmental Knowledge8 consider the Residential Researchers essential for supporting the knowledge flow between stakeholders for the sustainable and adaptive governance of local ecosystems. In this framework, the main role of the Residential Researchers is acting as knowledge collectors and translators, facilitating the communication, which is precisely what the BFAs do. The Galician BFAs fall within the concept of Residential Researchers.

Another important achievement of the BFAs has been the provision of good quality fisheries data (spatially and temporally), not only from official sales but also from catches, field surveys, and fishers’ knowledge. This is important for supporting a decision-making process based on organized and reliable information, another key element also highlighted by many authors (Berkes et al. 2001; García et al. 2008).

It is a must to generate both professional and personal confidence with fishers, based on the work concerning the fisheries management but also assisting them in solving small problems, and always being patient and allowing time for changes of mentality to happen (several TAs pers. comm.).

Some Weak Points of the TAs Program

But despite of the success, the TAs program still needs to be fully consolidated and reinforced in the Galician S-fisheries management system. Although it seemed that some kind of consolidation was achieved, five BFAs in small cofradías lost their jobs in the last 2 years. This is because of the weak financial status of many cofradías that have to assume in advance the cost of the program before getting the funds from the fisheries administration several months later. The current financial crisis in Spain leading to cuts in public government budgets is threatening the system, at least for the smaller cofradías, which may have no other chance than joining efforts and sharing TAs and its costs.

For this consolidation to happen and for developing the TAs program in the medium term, several weak points and TAs demands during past years should be addressed, including:

Create a real ongoing training program. SIGREMAR and AROUSA platforms were mostly based on the effort and commitment of particular individuals rather than on a fisheries administration commitment. Scientists of the Galician research institutions and the fisheries administration personal should be involved.

Supply of common sampling protocols and procedures for the spatial fisheries assessment like the Prince toolbox idea (Prince 2010), and establishment of reference points and indicators (not only biological, but also socioeconomic) for at least the main S-fisheries. In doing so, the mismatch between the spatial scale of fished populations and the assessment/management scale, suggested as a primary cause for failure in fisheries management (Hilborn et al. 2005) could be successfully tackled.

Establishment of a simple decision-tree framework to form a transparent decision-making process. A formal harvest strategy should be implemented to replace ad hoc decisions being made.

Improve coordination between TAs and FA biologists, to engage the new TAs in a common working environment.

Recognize the importance of social science skills for the TAs work. The Galician fisheries administration only considers the BFAs as biologists not recognizing their social role. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that social issues like community leaders, robust social capital, and clear incentives are of critical importance for promoting successful fisheries in co-management regimes (Gutiérrez et al. 2011). Social aspects should be in the core of the training program mentioned before.

Not neglecting the importance of having funds for addressing these weak points, it is not only a matter of money. A higher governmental commitment and recognition of the relevance of the BFAs role would improve the Galician co-management system. A collaborative environment, which still has not been fully created between TAs, fishers, managers, and scientists will be necessary to accomplish this task.

Moreover, the annual budget reserved by the Galician fisheries administration (about EUR 1 million) for funding the TAs program in 2013 should not be an impediment (compared with official sales of EUR 62 million by Galician S-fisheries in 2012) for keep developing this program in the future if cost-recovery systems were implemented for supporting part of the program costs.

Future Perspectives of the TAs Program

An important characteristic and novel of the Galician case is that none of this was initially conceived by the fisheries administration as a whole plan for managing shellfisheries (it was only an enhancing techniques plan for clams mariculture). Nevertheless, it naturally evolved into what it is today by following the ongoing necessities of the fisheries, fishers, and managers along years. The necessities are still unsatisfied, the BFAs have shown its relevance for the system, and different political parties have already been in charge of the regional government and showed their support to this plan. All of these factors allow us to think that this plan will be maintained in a near-mid future, at least as it is now, but we are not that optimist that the weak points highlighted will be soon addressed. The risk is that the initial impulse of the Galician BFAs, a committed and motivated group of young graduates with initiative for revitalizing the system, has somehow decelerated under a sense of status quo that is causing a lack of motivation for the future.

A way of moving forward would be to implement the BFAs and Exploitation and Management Plan model to, not only benthic resources from S-fisheries, but also semi-mobile/territorial resources like some decapods and cephalopods highly relevant in Galician shellfisheries (e.g., common spider crab—Maja squinado, common lobster—Homarus gammarus, common cuttlefish—Sepia officinalis, or common octopus—Octopus vulgaris).

The BFAs together with organized fisher, surveillance plans, FA technicians (extension workers, biologists, managers), a marine sanitary monitoring (INTECMAR), and higher critical mass and implication of the local universities and research institutes, allow us to envisage an optimistic scenario for the Galician S-fisheries in a near future.

Nevertheless, if Galicia seeks to consolidate a Primary Fisheries Management conceived by Cochrane et al. (2011) (the S-fisheries model has already achieved many of the characteristics proposed) additional efforts need to be made in the next years. But if Galician S-fisheries want to achieve Tertiary Management in a mid-term future a great shift is needed and there is no end in sight a movement like this inside the fisheries administration. We agree with Cochrane et al. (2011) that Primary Fisheries Management should be seen as a first and minimum benchmark for fisheries management. Achieving that benchmark is likely to lead to setting of higher goals, and building capital for Tertiary Management that seeks to optimize benefits should remain the long-term goal.

Conclusion

The case we have described here falls down within the Barefoot Ecologists concept coined by Prince (2003, 2010) (although we consider that Barefoot Fisheries Advisors is a more appropriate name), that he defined as:

an ethno-socio-quantitative fisheries ecologists for catalyzing a change and building social capital within the fishers communities, and with the main role of motivating and empowering fishers to research, monitor and manage their own resources.

Prince based on Berkes et al. (2001) work, who noted that:

small-scale fisheries need a new set of skills and capabilities, people who can work on the interface among science, industry, and management, envisaging this role as being filled by a mediator/synthesizer, an objective and knowledgeable third party who can cope with inputs from both scientific/technical and industry stakeholders.

Twelve years have passed since the work of Berkes et al., but we still have not found any paper describing/analyzing a particular case in any small-scale fisheries, although we know about some initiatives in other parts of the world. We have shown the key role the BFAs are playing in Galician S-fisheries, and their main contributions and achievements. The description of similar BFAs cases is necessary for analyzing the role of this figure in management and governance schemes of small-scale fisheries. This effort is even more necessary since there is almost no information available even in gray literature. A worldwide review of cases on models for providing technical/scientific support in small-scale fisheries is necessary for exploring the potential of BFAs in fostering the transition from primary to tertiary management.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We are in debt with all Asistencias Técnicas in Galicia and the Asociación Galega de Técnicos en Xestión de Recursos Mariños for helping us reconstruct the historical evolution, their comments, help, and daily work. Special thanks to Pedro Ferreiro, Beatriz Nieto, Andrés Simón, Jose-Manuel Parada, Emilio Abella, José Rios, Marta Miñambres, Alberto Garazo, and Carlos Mariño whose collaboration and suggestions were very helpful along this study. Lobo Orensanz, Ana Parma, and Jeremy Prince have been a suggestive discussion forum along years of immense value. The recent visit to Galicia of the ILEK project, leaded by Tetsu Sato, for knowing the TAs model acted as a catalyst for publishing this work. GM and SV thank to World Wide Fund for Nature and Environmental Defense Fund for the kindly invitation to a series of workshops on artisanal fisheries and the fruitful discussions experienced there. The authors also thank Bo Söderström (Editor-in-Chief) for his valuable comments and suggestions that improved the final version of this paper.

Biographies

Gonzalo Macho

is a joint Postdoctoral Researcher (PhD in Marine Ecology) at the Universidade de Vigo (Spain) and the University of South Carolina (USA). His research interests include socioeconomics and governance of small-scale fisheries, marine social–ecological systems, climate change effects over species and fisheries, and marine invertebrate population dynamics.

Inés Naya

is a postgraduate researcher at the Universidade da Coruña (Spain). Her current interests include small-scale fisheries management, shellfish resources specially sea urchins, marine invertebrate’s population dynamics, modeling and models for providing technical/scientific support.

Juan Freire

is a Professor in marine conservation and management at the Universidade da Coruña (Spain) and an entrepreneur. His professional activity is focus on researching, consulting, design, implementation and management of projects about: strategy and management of innovation in organizations, environmental, rural and territorial management, cultural management and production, digital culture and education, among others.

Sebastian Villasante

is a Researcher and Professor (PhD in Economics) at the University of Santiago de Compostela and Karl-Göran Mäler Scholar at The Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics. His research interests include environmental economics, ecosystem services, and marine social–ecological systems.

José Molares

is a fishery and marine ecology researcher at CIMA and the current Deputy Director of investigation and scientific–technical advice at the Consellería de Medio Rural e do Mar. His research focuses on marine invertebrate’s population dynamics, small-scale fisheries management, benthic stock assessment, and Geographic Information Systems.

Footnotes

The Spanish original name is Asistencias Técnicas en la Gestión de Recursos Marisqueros and do not exist in any other Spanish region, but Galicia.

The Galician fisheries administration is the Consellería do Medio Rural e do Mar (http://www.medioruralemar.xunta.es/mar/).

This unit (known as Unidade Técnica de Pesca de Baixura) belongs to the Galician fisheries administration but it is more focused on providing advice for coastal fisheries targeting mobile resources like crustaceans, cephalopods, and fishes.

The law referred is the Ley 59/1969 de Ordenación Marisquera and the decree referred is the Decreto 1238/1970: Plan de Explotación Marisquera de Galicia.

Plan 10 was officially known as Programa de desenvolvemento da acuicultura de moluscos nas praias de Galicia (Program for molluscs aquaculture development in the beaches of Galicia).

Plan Galicia was officially known as Programa de Desenvolvemento Productivo, Económico, Profesional e Organizativo do Marisqueo a Pé (Program for Productive, Economic, Professional and Organizational Development of the Afoot Shellfishing).

Data from Plan Xeral de Ordenación Marisqueira 2011 published in the Diario Oficial de Galicia, the Official Journal of the Galician government.

The Integrated Local Environmental Knowledge (ILEK) is considered a blend of diverse types of knowledge from, e.g., fishers, scientists, managers, the local community, NGOs, or any other person/institution involved in a social–ecological system. More information about the ILEK project is available at its web page: http://en.ilekcrp.org/.

Contributor Information

Gonzalo Macho, Email: gmacho@uvigo.es.

Inés Naya, Email: inesnaya@gmail.com.

Juan Freire, Email: juan.freire@gmail.com.

Sebastián Villasante, Email: sebastian.villasante@usc.es.

José Molares, Email: jmolares@gmail.com.

References

- Arnáiz R. A revisión da Pesca de Baixura en Galicia. O Grove: IV Foro dos Recursos Mariños e da Acuicultura das Rías Galegas; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes F, Mahon R, McConney P, Pollnac R, Pomeroy R. Managing small-scale fisheries: Alternative directions and methods. Ottawa: IRDC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter SR, Mooney HA, Agard K, Capistrano D, De Fries RS, Díaz S, Dietz T, Duraiappah AK, et al. Science for managing ecosystem services: Beyond the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:1305–1312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808772106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane KL. Complexity in fisheries and limitations in the increasing complexity of fisheries management. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 1999;56:917–926. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.1999.0539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane KL, Andrew NL, Parma AM. Primary fisheries management: A necessary but not sufficient approach to provision of sustainable human benefits. Fish and Fisheries. 2011;12:275–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00392.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Consellería do Medio Rural e do Mar. 2013. Xunta de Galicia. Retrieved August 10, 2013, from http://conselleriamar.xunta.es/web/pesca and www.pescadegalicia.com.

- Costello CC, Ovando D, Hilborn R, Gaines SD, Deschenes O, Lester SE. Status and solutions for the world’s unassessed fisheries. Science. 2012;26:517–520. doi: 10.1126/science.1223389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of the World’s Fisheries and Aquaculture 2012. Rome: FAO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frangoudes K, Marugán-Pintos B, Pascual-Fernández J. From open access to co-governance and conservation: The case of women shellfish collectors in Galicia (Spain) Marine Policy. 2008;32:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2007.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franquesa, R. 2004. Las cofradías en España: papel económico y cambios estructurales. 12th Conference of the International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (IIFET), Tokio, Japan.

- Freire, J. 2000. El papel de la investigación científica como apoyo al sector pesquero artesanal. In Taller “Pesca artesanal y sostenibilidad en España y Latinoamérica”, A Coruña, Spain.

- García, S.M., E.H. Allison, N.J. Andrew, C. Béné, G. Bianchi, G.J. de Graaf, D. Kalikoski, R. Mahon, and J.M. Orensanz. 2008. Towards integrated assessment and advice in small-scale fisheries: Principles and processes. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 515. Rome: FAO.

- González-Vidal M. El conflicto en el sector marisquero de Galicia. Madrid: Akal; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez N, Hilborn R, Defeo O. Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries. Nature. 2011;470:386–389. doi: 10.1038/nature09689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilborn R. The state of the art in stock assessment: Where we are and where we are going? Scientia Marina. 2003;67:5–12. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2003.67s115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilborn R, Orensanz JM, Parma AM. Institutions, incentives and the future of fisheries. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2005;360:47–57. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes RE. The case for data-less marine resource management: Examples from tropical nearshore finfisheries. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1998;13:243–246. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Veiga CE, Carballeira D, Penas E, Caamaño J, Aguirre P, Pastor A, Fernandez-Domonte F, Juarez S, et al. Plan de ordenación dos recursos pesqueiros e marisqueiros de Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: Consellería de Pesca, Marisqueo e Acuicultura, Xunta de Galicia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mahou XM. Implementación y gobernanza: la política de marisqueo en Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: Escola Galega de Administración Pública (EGAP); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Molares J, Freire J. Development and perspectives for community-based management of the goose barnacle (Pollicipes pollicipes) fisheries in Galicia (NW Spain) Fisheries Research. 2003;65:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2003.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orensanz JM, Parma A, Jerez G, Barahona N, Montecinos M, Elias I. What are the key elements for the sustainability of “S-fisheries”? Insights from South America. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2005;76:527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2007;104:15181–15187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702288104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada JM, Molares J. Artisanal exploitation of natural clam beds: Organization and management tools. In: da Costa F, editor. Clam fisheries and aquaculture. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.; 2012. pp. 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Prince JD. The barefoot ecologist goes fishing. Fish and Fisheries. 2003;4:359–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2979.2003.00134.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prince JD. Rescaling fisheries assessment and management: A generic approach, access rights, change agents, and toolboxes. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2010;86:197–219. doi: 10.5343/bms.2009.1075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Punt AE, Smith ADM, Cui G. Review of progress in the introduction of management strategy evaluation (MSE) approaches in Australia’s south east fishery. Marine & Freshwater Research. 2001;52:719–726. doi: 10.1071/MF99187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury KJ, Punt AE, Smith ADM. Design of operational management strategies for achieving for achieving operational fishery ecosystem objectives. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2000;57:731–741. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2000.0737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., N. Kikuchi, T. Miyauchi, H. Niitsuma, S. Tomita, Y. Suga, H. Matsuda, A. Sakai, et al. 2013. Creation and Sustainable Governance of New Commons through Formation of Integrated Local Environmental Knowledge (ILEK project). Retrieved August 24, 2013, from http://en.ilekcrp.org/.

- Taboada MS. Las prácticas contables de las cofradías de pescadores gallegas. la coerción como vehículo de institucionalización cultural normativa. Revista Galega de Economía. 2007;16:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Villasante S. The management of the blue whiting fishery as complex social–ecological system: The Galician case. Marine Policy. 2012;36:1301–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villasante S, Sumaila R. Estimating the effects of technological efficiency on the European Union fishing fleet. Marine Policy. 2010;34:720–722. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2009.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters C, Pearse PH. Stock information requirements for quota management systems in commercial fisheries. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 1996;6:21–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00058518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Prince JD, Lenihan HS. A management strategy for sedentary nearshore species that uses marine protected areas as a reference. Marine and Coastal Fisheries: Dynamics, Management and Ecosystem Science. 2010;2:14–27. doi: 10.1577/C08-026.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worm B, Hilborn R, Baum JA, Branch TA, Collie JS, Costello C, Fogarty MJ, Fulton EA, et al. Rebuilding global fisheries. Science. 2009;325:578–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1173146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.