Abstract

Background

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the association between the acromial index (AI) and the incidence of recurrent tears of the rotator cuff (RC) in a cohort of patients with full thickness tears who underwent arthroscopic primary repair.

Methods

A prognostic study of a prospective case series of 103 patients with full thickness RC tears was undertaken. The average age was 59.5 years (39–74) and follow-up was 30.81 months (12–72). True anterior–posterior X-rays were obtained during the pre-operative evaluation. Pre and post-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were recorded.

Results

Eighteen cases with recurrent tears (17.4 %) were seen on post-operative MRI. The average AI for patients with recurrent tears was 0.711 ± 0.065 and for patients without recurrent tears 0.710 ± 0.064 (p < 0.05). A positive association between age and recurrent tears of the RC was noted (average ages: recurrent tears group 63 ± 5.9 years; group without recurrent tears 58.8 ± 7.5 years) (r = −0.216; p = 0.029). We did not find an association between size of the primary tear and recurrent tears (r = −0.075; p < 0.05) or between degrees of retraction of the primary and recurrent tears of the cuff (r = −0.073; p < 0.05). We observed that 38.9 % of the recurrent tears cases presented with more than one tendon affected before the arthroscopy. At follow-up, none of these recurrent tears showed more than one tendon affected on MRI evaluation.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that the AI radiological measurement is not a predictor for recurrent tears of the RC after primary arthroscopic repair.

Introduction

Currently the causes for recurrent tears of the rotator cuff (RC) tendons after reconstruction are poorly understood. It has been stated that intrinsic factors such as age of the patients, size of the tear, fatty degeneration and retraction of the affected tendons may play a role as predictors for recurrent tears after successful surgery [1–7]. Regardless, at this point, the only clear predictor that positively correlates with a higher recurrent tear rate seems to be the age of the patient at the moment of surgical intervention [2, 5, 7, 8].

Concerning the pathogenesis of primary RC tears, there is considerable debate about the main factor responsible for this pathology. On the one hand, some authors support an intrinsic theory of damage, in which the degeneration of the tendon in aged patients would be the primary cause of the tear [9–11]. Others favour an extrinsic theory, where the RC tendons are chronically damaged by an impingement phenomenon, mainly under the anterior and lateral part of the acromion. This matter could be considered in the aetiology for recurrent tears of the RC after primary repair [12–14].

Other authors have investigated the lateral extension of the acromion on the humeral head (acromion index, AI) and its relationship with tearing of the RC, documenting that those patients with complete tears have a significantly larger AI, compared with individuals with an intact cuff [15–19].

Unlike others factors such as age, fatty degeneration or size of the primary tear, the morphology of the acromion is a factor that can be surgically modified by partially excising the anterior and lateral portion when performing an acromioplasty and subacromial decompression during arthroscopic repair of the RC.

Currently, there is no evidence that greater AI measurements correlate with increased incidence of recurrent tears after primary repair of full thickness RC tears; in an attempt to clarify this matter, we conducted a prognostic study of a prospective case series.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the association between AI and the incidence of recurrent tears of the RC in a cohort of patients with full thickness tears, who underwent arthroscopic primary repair.

The hypothesis of this investigation was that patients with a larger AI present a higher rate of recurrent tears of the RC after primary arthroscopic repair.

Methods

A prognostic study of a prospective case series (patients enrolled at different points in their disease and over 80 % of the series were included in the follow up) of 103 patients with full thickness RC tears underwent an arthroscopic reconstruction between 2003 and 2006, performed by one of the two senior authors.

All RC patients that undergo arthroscopic repair at our institution are included in a cross-platform relational database application program (File Maker Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The cases from this study were collected from the database in order to evaluate clinical, arthroscopic and descriptive data from the series. Patients were prospectively assessed in order to determine the incidence of recurrent tears of the RC using retrospective collection of data. Part of these series of cases was previously analysed in a different study and are included in the present report [20].

The average time of follow-up for the series was 30.81 months (range 12–72); at this time the post operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was requested. There were 33 females and 70 males with an average age of 59.5 years (range 39–74) at the time of the arthroscopic intervention. Surgery was performed in 71 patients in the right shoulder and in 32 cases in the left side. In 53 cases the dominant side was affected.

We documented that 61 patients suffered a traumatic RC tear and 43 a degenerative tear without acknowledged trauma.

The inclusion criteria were: (a) traumatic or degenerative aetiology of the rupture, (b) RC primary rupture repaired arthroscopically, and (c) single or double row arthroscopic reconstruction.

The exclusion criteria for our study were: (a) patients with partial tears, (b) partial reconstruction of the SSP tendon, (c) frozen shoulder, (d) glenohumeral osteoarthritis, (e)upward migration of the humeral head with acromio–humeral distance less than five millimetres, and (f) severe muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration more than stage III according to Thomazeau et al. [21].

Surgical technique

An arthroscopic reconstruction of the RC was performed in all 103 patients. Single row reconstruction using a modified Mason–Allen suture stitch was performed in 76 patients, with one to three peek or bioabsorbable, double loaded, 5.5-mm anchors (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL, USA). Double row reconstruction with two to three peek or bioabsorbable double loaded 5.5-mm anchors for the proximal row and two 4.5-biocomposite Push–Lock anchors (Arthrex Inc.), for the lateral row, was performed in 27 patients.

General anaesthesia and interscalenic plexus nerve block for adequate postoperative analgesia were used in the entire case series. The procedure was performed with the patients placed in the beach chair position. Diagnostic arthroscopy was performed through a standard posterior arthroscopic portal. Afterwards the scope was placed in the subacromial space and any outlet impingement was diagnosed and treated using a 4.5 or 5.0 burr (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL, USA) using a combined acromioplasty surgical technique, where initially about five millimetres of anterior and lateral border of the acromion were resected until the acromio–clavicular joint was reached, afterwards the scope was placed in the anterior and lateral portal and the shaver in the posterior portal to smooth the resected border [22]. The scope was later placed in this portal to perform the bursectomy and to adequately visualise the size, configuration and retraction of the tear. To perform the surgery on the long biceps tendon (tenotomy or tenodesis) and on the RC, the scope was placed in a posterolateral portal. Interarticular and/or subacromial mobilisation of the cuff was performed at this time. Debridement of the footprint was also performed during the same step. An anterior superior portal was created to position the anchors and to “park” the sutures.

Acromioplasty was performed in all but three patients, where an appropriate subacromial space was subjectively documented during the surgery. Arthroscopic long biceps tenodesis was performed in 35 patients, using a 4.5-biocomposite Push–Lock anchor (Arthrex Inc.). Tenotomy was done in 24 cases. Reconstruction of the RC was performed using standard surgical technique.

Patients remained three days in hospital for analgesic treatment. The shoulders were immobilised for three weeks in a 15° abduction pillow. Passive range of motion of the shoulder began on the first postoperative day and was limited to 60° of abduction and 30° of external rotation for six weeks. Active range of motion was started once the shoulder had gained free forward elevation. Strengthening exercises were carried out for a minimum of four months.

Radiographic analysis

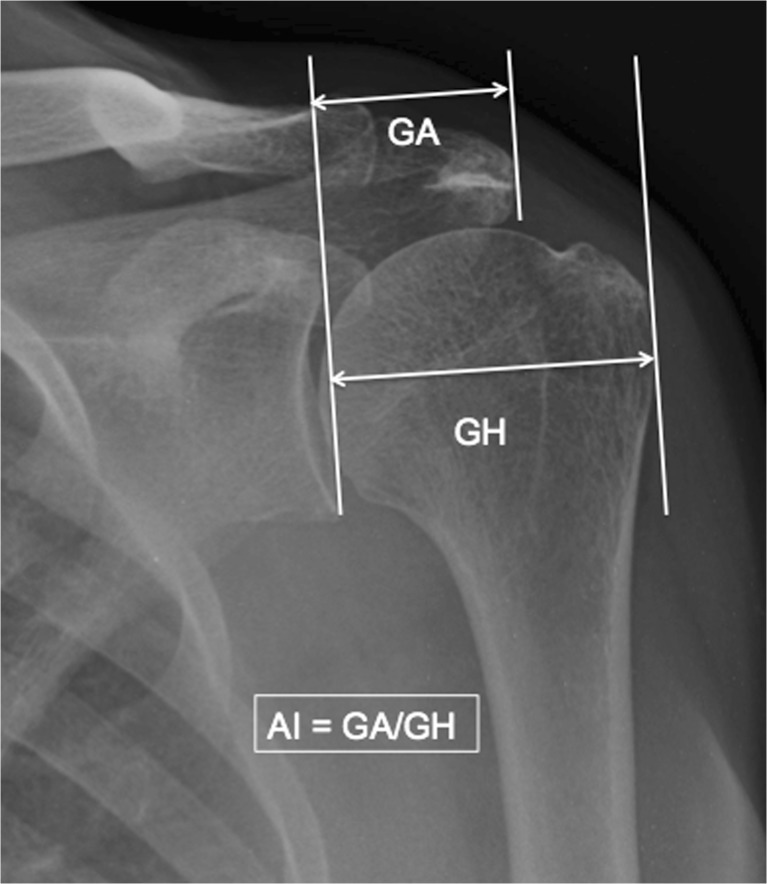

The AI was measured and calculated by two independent observers on preoperative standardised, true anterior–posterior radiographs according to Nyffeler et al. [17]. A first line connecting the superior and inferior osseous margins of the glenoid cavity, representing the plane of the glenoid articular surface was drawn. Second and third parallel lines were drawn at the lateral border of the acromion and at the most lateral border of the proximal part of the humerus, respectively. The distance between the glenoid to the acromion (GA) and the distance from the glenoid to the lateral part of the humerus at the greater tuberosity (GH) were measured and AI was calculated as the relationship between these two measurements (GA/GH) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

In this figure we observe a true anteroposterior X-ray of the left shoulder, where the acromial index (AI) was measured according to Nyffeler et al. [17]. GH gleno–humeral distance, GA glenoid–acromion distance

MRI evaluation

All 103 patients underwent a standardised open MRI (ESAOTE E-scan XQ, Esaote S.p.A, Genova, Italy) examination preoperatively and then at 24 months follow-up. MRI was performed using a shoulder coil with paracoronal T1-weighted spin-echo sequences, paracoronal T2-weighted turbo spin echo, parasagittal T1-weighted spin echo sequences and transaxial T1-weighted spin echo sequences.

The MRIs were evaluated by one of two independent observers. On the preoperative MRI, classification of the cuff retraction according to Patte was performed [23]. Recurrent tears of the cuff were reviewed in the postoperative MRI; recurrent tear was defined as the lack of continuity of the tendon and footprint interphase in one slice of the MRI in the coronal plane. Postoperative evaluation of muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff was not performed in this study.

Statistical analysis

All measured results were transferred into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to perform statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were carried out to calculate the means and standard deviations (SD). Wilcoxon-signed-rank test was used to analyse the pre and postoperative results. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the mean AI index in patients with traumatic and degenerative tears; mean AI in patients with and without re-tearing of the RC; mean AI in patients with and without re-tears in the degenerative RC tears group. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between the AI and (1) size of the tear, (2) retraction of the tendon and (3) age of the patient. To compare the means and to identify any relationship between acromion index and the results, a paired Student t-test was used. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Source of funding

This study was funded by departmental funds, which were used to pay the costs for imaging. There was no exterior source of funding that could have played a role in the investigation.

Results

Radiographic and MRI outcomes

There were 18 cases with recurrent tears (17.4 %) of the RC in the entire group, revealed by a post operative MR (Fig. 2). Eight of these were found in the degenerative tears group. We observed that seven of these cases had more than one tendon involved initially and all but one case (where the subscapularis [SSC] developed a recurrent tear), revealed postoperative rupture of the supraspinatus (SSP) tendon. In Table 1 we present a detailed description of the initial tear configuration, describing the degree of muscle atrophy according to Thomazeau [21] and the degree of retraction according to Patte [23].

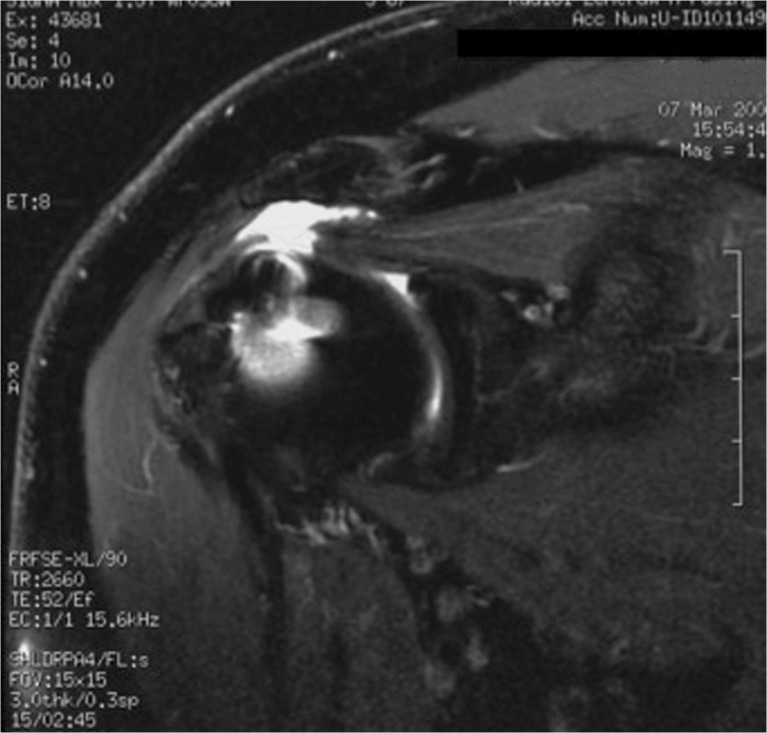

Fig. 2.

In this figure we observe a coronal T2 sequence MRI image of a failed RC repair. An adequate subacromial space is observed; failure is located medial to the repair

Table 1.

We describe the initial tear configuration, describing the degree of muscle atrophy according to Thomazeau [21] and the degree of retraction according to Patte [23]

| Case | Age | Post-op AI | Pre operative findings | Post operative findings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruptured tendons | Batemann | Patte | Atrophy Thomazeau | Ruptured tendons | Patte | Atrophy Thomazeau | |||

| 1 | 68 | 0.75 | SSP | 2 | 1 | 2 | SSP partial tear | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 69 | 0.78 | SSP, ISP, SCP | 2 | 2 | 2 | SSP | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 63 | 0.73 | SSP, ISP | 3 | 3 | 2 | SSP | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 67 | 0.72 | SSP | 2 | 1 | 2 | SSP | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | 66 | 0.76 | SSP | 3 | 2 | 2 | SSP | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | 54 | 0.72 | SSP | 2 | 2 | 1 | SSP | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | 74 | 0.75 | SSP | 1 | 1 | 1 | SSP partial tear | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | 59 | 0.68 | SSP | 1 | 2 | 2 | SSP | 0 | 2 |

| 9 | 55 | 0.7 | SSP, SCP | 2 | 2 | 1 | SSP | 2 | 3 |

| 10 | 68 | 0.57 | SSP, ISP | 2 | 2 | 1 | SSP | 3 | 2 |

| 11 | 73 | 0.69 | SSP, SCP | 2 | 1 | 1 | SCP | 1 | 2 |

| 12 | 59 | 0.63 | SSP | 2 | 2 | 2 | SSP | 1 | 3 |

| 13 | 74 | 0.62 | SSP | 2 | 1 | 1 | SSP | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | 70 | 0.68 | SSP | 1 | 1 | 2 | SSP | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | 65 | 0.7 | SSP, ISP | 2 | 2 | 2 | SSP | 2 | 3 |

| 16 | 68 | 0.72 | SSP, ISP, SCP | 2 | 2 | 1 | SSP | 1 | 2 |

| 17 | 71 | 0.71 | SSP | 3 | 2 | 1 | SSP | 2 | 2 |

| 18 | 70 | 0.69 | SSP | 1 | 1 | 1 | SSP | 1 | 1 |

AI acromion index, SSP supraspinatus, ISP infraspinatus, SCP subscapularis

We have shown a positive association between age and recurrent tears of the RC tendons (average age for the recurrent tears group of 63 ± 5.9 years; average age for group without recurrent tears 58.8 ± 7.5 years) (r = −0.216; p = 0.029).

In Table 2, we describe all the analysed factors. None of the remaining evaluated parameters presented significant differences.

Table 2.

Findings documented when correlating age, acromion index (AI), recurrent tear and size of the rupture

| Variable | Test | Age | AI | Recurrent tear | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Pearson | 1 | −0.085 | −0.216a | −0.079 |

| P value | – | 0.392 | 0.029 | 0.426 | |

| AI | Pearson | −0.085 | 1 | −0.031 | −0.033 |

| P value | 0.392 | – | 0.754 | 0.744 | |

| Recurrent tear | Pearson | −0.216a | −0.031 | 1 | −0.075 |

| P value | 0.029 | 0.754 | – | 0.454 | |

| Size | Pearson | −0.079 | −0.033 | −0.075 | 1 |

| P value | 0.426 | 0.744 | 0.454 | – |

a Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

We observed that seven cases (38.9 %) of the recurrent tears cases (18 cases) had more than one tendon affected before the arthroscopy. At follow up, none of these recurrent tears presented more than one tendon affected on MRI evaluation.

In Table 3 we present the documented values for the AI in degenerative and traumatic RC tears. No differences were documented amongst AI measurements.

Table 3.

In this table present the documented values for the AI in degenerative and traumatic RC tears. No differences were documented amongst AI measurements

| Type of tear | AI | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Recurrent tears | Intact cuff | ||

| Degenerative tears | 0.708 ± 0.065 | 0.704 ± 0.086 | 0.710 ± 0.6 | p > 0.05 |

| Traumatic tears | 0.713 ± 0.064 | 0.708 ± 0.5 | 0.714 ± 0.06 | p > 0.05 |

| p value | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | |

AI acromion index, RC rotator cuff

Analysing the recurrent tears of the RC group (18 cases), we observed that in ten patients (55.6 % with average AI of 0.71) the technique used during arthroscopy was a double-row repair and that in eight cases (44.4 % with average AI of 0.73) a single-row repair was performed (P = 0.243).

Discussion

Nowadays there is still considerable controversy regarding the pathogenesis of RC tears and the causes of recurrent tears of the repaired tendons. Early in the last century Codman and Akerson [24] stated that while most of the RC tears result from a traumatic event, the primary source is degenerative. Ozaki et al. [25], by studying partial articular tears in cadaveric specimens, proposed that age-related degenerative changes in the RC are the cause of the subsequent tears. Several other authors are in favour of an intrinsic degenerative aetiology as the main cause for RC pathology [26, 27].

On the other hand, since Armstrong et al. [28] in 1949 proposed that a painful arc of motion of the shoulder was caused by impingement of the SSP tendon under the bursa and the acromion, and later with Neer [29] stating that up to 95 % of the RC injuries are caused by chronic impingement under the acromion, many authors have focused their research on the relationship between RC injuries and different characteristics of the acromial bone, such as its shape, the anterior acromion slope, the lateral angle of the acromion and lately the lateral extension of the acromion over the humeral head [30, 31].

Indeed, Nyffeler et al. [17] studied a group of 102 patients (average age 65.0 years) with a full thickness RC tear, in an age- and gender-matched group of 47 patients (average age 63.7 years) with osteoarthritis of the shoulder and an intact RC, and an age- and gender-matched control group of seventy volunteers (average age 64.4 years) with an intact RC as demonstrated by ultrasonography; they documented significant differences between the AI of patients with complete tears of the RC 0.73 ± 0.06 and patients with an intact RC, 0.60 ± 0.08 in those with osteoarthritis and an intact cuff, and 0.64 ± 0.06 in the asymptomatic, normal shoulders with an intact cuff. The difference between the AI in the shoulders with a full thickness SSP tear and the AI in those with an intact rotator cuff was highly significant (p < 0.0001).

Furthermore, Torrens et al. [18], measuring the lateral extension of the acromion using a different method (acromial coverage index), found significant differences in the values between patients with RC tear (with and without surgery) and those patients with an intact cuff. These authors evaluated 148 shoulders, including 45 that underwent surgical RC repair (group I), 26 with documented RC tears treated conservatively (group II), and 77 with no cuff pathology as a control group (group III). They reported an average acromial coverage index was 0.68 in group I, 0.72 in group II, and 0.59 in group III, reporting a significant difference (P < 0.0001) between the control group and both cuff tear groups. The authors reported that patients with a cuff tear have a significantly higher acromial coverage index than the control group.

Afterwards, Zumstein et al. [32] reported a cohort of patients who underwent open repair of the RC at a mean follow-up of 9.9 years. They found a larger AI in patients with recurrent tears of the RC compared to those without failure. The arguments advanced to explain why a greater lateral extension of the acromion may be a risk factor for tearing and recurrent tearing of the RC, have mostly to do with the function of the deltoid muscle. Patients with an increased AI, having in consequence a lateralised insertion of the deltoid would have a greater ascending vector force of the humeral head, which would impinge under the acromion, causing chronic degenerative damage and ultimately tearing of the RC. On the other hand, patients with a lower AI, would have a more medial insertion of the deltoid, and then major compression forces over the glenoid cavity, which could theoretically determine a higher incidence of osteoarthritis.

In our results, the overall recurrent tears incidence was 17 %. We found no correlation between recurrent tears rate and preoperative size and retraction of the RC. The only positive correlation we documented was between recurrent tears rate and age, as is described also in previous studies [17–20, 33].

We also noted, that the mean AI for the entire group was 0.72, which is in concordance with the values reported in the study of Nyffeler et al. [17]. However, we found no positive correlation between a larger acromion index and the incidence of recurrent tears of the RC. In our study, no differences were encountered between the AI of traumatic or degenerative lesions of the RC.

Analysing the recurrent tears of the RC group (18 cases), we observed that in ten cases (55.6 % with average AI of 0.71) the technique performed during arthroscopy was a double-row repair and that in eight cases (44.4 % with average AI of 0.73) a single-row repair was performed (P = 0.243). We found no significant differences amongst groups once we analysed the incidence of recurrent tears, AI average and surgical technique used for arthroscopic repair.

A weakness of the study is that we did not document the AI in cases without subacromial impingement clinical findings to have a disease-free control group. This perhaps would have given stronger significance to the statistical findings we presented, reporting sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the AI measurement as a tool to evaluate prognostic factors on RC recurrent tears after primary repair.

We cannot explain why we found different results in our study when comparing our findings to some reports currently discussed in the literature [15–19, 32]; although, we consider that one important factor to explain the divergent results, is the fact that the imaging X-rays studies will unavoidably present bias amongst the projection of the X-ray beam in the patient, the spatial position of the evaluated joint, the morphology of the patient and finally the bias amongst evaluators of the indexes to be measured. Further studies are needed to support this hypothesis.

Conclusion

In our study, we found that the AI radiological measurement is not a predictor for RC recurrent tears after primary arthroscopic repair.

References

- 1.Pfalzer F, Endele D, Huth J, Bauer G, Mauch F. Clinical and MRI results after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using the double-row technique. A consecutive study. [Klinische und magnetresonanztomographische Ergebnisse nach arthroskopischer Rotatorenmanschettenrekonstruktion in “Double-row”-Technik. Eine serielle Studie] Obere Extremitat. 2011;6(4):267–274. doi: 10.1007/s11678-011-0117-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papadopoulos P, Karataglis D, Boutsiadis A, Fotiadou A, Christoforidis J, Christodoulou A. Functional outcome and structural integrity following mini-open repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears: a 3-5 year follow-up study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanusch BC, Goodchild L, Finn P, Rangan A. Large and massive tears of the rotator cuff: functional outcome and integrity of the repair after a mini-open procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am B. 2009;91(2):201–205. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummins CA, Murrell GAC. Mode of failure for rotator cuff repair with suture anchors identified at revision surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):128–133. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller BS, Downie BK, Kohen RB, Kijek T, Lesniak B, Jacobson JA, Hughes RE, Carpenter JE. When do rotator cuff repairs fail? Serial ultrasound examination after arthroscopic repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2064–2070. doi: 10.1177/0363546511413372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho NS, Lee BG, Rhee YG. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using a suture bridge technique: is the repair integrity actually maintained? Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2108–2116. doi: 10.1177/0363546510397171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluger R, Bock P, Mittlböck M, Krampla W, Engel A. Long-term survivorship of rotator cuff repairs using ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2071–2081. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Techniques for managing poor quality tissue and bone during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(10):1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laron D, Samagh SP, Liu X, Kim HT, Feeley BT. Muscle degeneration in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(2):164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang JR, Gupta R. Mechanisms of fatty degeneration in massive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolbe AB, Collins MS, Sperling JW. Severe atrophy and fatty degeneration of the infraspinatus muscle due to isolated infraspinatus tendon tear. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(1):107–110. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison AK, Flatow EL. Subacromial impingement syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(11):701–708. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadonikolakis A, McKenna M, Warme W, Martin BI, Matsen FA., III Published evidence relevant to the diagnosis of impingement syndrome of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am A. 2011;93(19):1827–1832. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garofalo R, Karlsson J, Nordenson U, Cesari E, Conti M, Castagna A. Anterior-superior internal impingement of the shoulder: an evidence-based review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(12):1688–1693. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JR, Ryu KJ, Hong IT, Kim BK, Kim JH. Can a high acromion index predict rotator cuff tears? Int Orthop. 2012;36(5):1019–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1499-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyazaki AN, Itoi E, Sano H, Fregoneze M, Santos PD, da Silva LA, Sella Gdo V, Martel EM, Debom LG, Andrade ML, Checchia SL. Comparison between the acromion index and rotator cuff tears in the Brazilian and Japanese populations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1082–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):800–805. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.03042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torrens C, López JM, Puente I, Cáceres E. The influence of the acromial coverage index in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(3):347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sukthankar A, Werner CM, Brucker P, Nyffeler RW, Gerber C. Lateral extension of the acromion and rotator cuff tears—a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91-B(Supp I):123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichtenberg S, Liem D, Magosch P, Habermeyer P. Influence of tendon healing after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair on clinical outcome using single-row Mason-Allen suture technique: a prospective, MRI controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(11):1200–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomazeau H, Rolland Y, Lucas C, Duval JM, Langlais F. Atrophy of the supraspinatus belly: assessment by MRI in 55 patients with rotator cuff pathology. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:264–268. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P, Magosch P (2008) Atlas Schulterarthroskopie. Urban & Fischer by Elsevier, first edition. Arthroskopische Chirugie des Subakromialraums, pp 124–126

- 23.Patte D. Classification of rotator cuff lesions. Clin Orthop. 1990;254:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Codman EA, Akerson IB. The pathology associated with rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. Ann Surg. 1931;93(1):348–359. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193101000-00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nakagawa Y, Masuhara K, Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1224–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald P, McRae S, Leiter J, Mascarenhas R, Lapner P. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with and without acromioplasty in the treatment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):1953–1960. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadonikolakis A, McKenna M, Warme W, Martin BI, Matsen FA., 3rd Published evidence relevant to the diagnosis of impingement syndrome of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(19):1827–1832. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstrong JR. Excision of the acromion in treatment of the supraspinatus syndrome; report of 95 excisions. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31B(3):436–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neer CS., 2nd Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bigliani LU, Ticker JB, Flatow EL, Soslowsky LJ, Mow VC. The relationship of acromial architecture to rotator cuff disease. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10:823–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacGillivray JD, Fealy S, Potter HG, O‘Brien SJ. Multiplanar analysis of acromion morphology. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(6):836–840. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260061701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zumstein MA, Jost B, Hempel J, Hodler J, Gerber C. The clinical and structural long-term results of open repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(11):2423–2431. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, Carles M, Hatzidakis AM, Krishnan SG. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1229–1240. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]