Abstract

A cross-sectional survey of community pharmacists in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia was conducted over a period of 6 months from July through December 2011. Data collection was carried out using a structured self-administered questionnaire. The survey questionnaire consisted of a brief introduction to the study and eleven questions. The questions consisted of close ended, multiple-choice, and fill-in short answers. A stratified random sample of one thousand and seven hundred registered pharmacy practitioners all over Saudi Arabia were randomly chosen to respond to the survey. The data from each of the returned questionnaire were coded and entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) which was used for statistical analysis. Only one thousand four hundred one pharmacists responded to the survey (response rate is 82.4%) with a completely answered questionnaire. The study results show that 59.7% of the participants sometimes discuss herbal medicine use with their patients, while only 4.25% never discuss it. The study shows 48.5% of participated pharmacists record herbal medicine use sometimes where only 9.4% of them never did so. However, with regard to initiation of the discussion, the study shows that 44.3% of the respondents reported that patients initiate herbal issue discussion while 20.8% reported that pharmacists initiate the discussion. This discussion was reported to be a one time discussion or an ongoing discussion by 14.3% or 9.9% of the respondents respectively. According to the study results, respondents reported that the most common barriers that limit discussing herbal medicines’ use with their patients were lack of time due to other obligations assigned to the community pharmacist (46%), lack of reliable resources (30.3%), lack of scientific evidence that support herbal medicine use (15.2%), or lack of knowledge of herbal medicines (13.4%). Yet, a small number of respondents was concerned about interest in herbal medicines (9.1%) and other reasons (2.4%). So it is urgent to ensure that pharmacists are appropriately educated and trained. Extra efforts are needed to increase the awareness of pharmacists to adverse drug reactions reporting system at Saudi Food and Drug Authority. Finally, more consideration to herbal issues should be addressed in both pharmacy colleges’ curricula and continuous education program..

Keywords: Recourse, Medicinal, Herbal, Availability

1. Introduction

The safety and efficacy of many herbal medicines used remain essentially unknown. However, the potential benefits of herbal medicines could lie in their high acceptance by patients and lay public, efficacy, relative safety and relatively low cost. The use of herbal medicines continues to expand globally, in parallel to an increasing acceptance of herbal remedies by consumers. Despite the fact that herbal remedies are not classified as drugs by the United States (US) Food and Drug administration (FDA) Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act, 1994, the attitude of the general population toward herbal medicine is that this kind of therapy is natural and therefore safe (Zaffani et al., 2006). So despite the potential for harmful side effects (De Smet, 1995) and interactions with conventional drugs (Williamson, 2003; Chavez et al., 2006), natural products are often taken on a self medication basis, without the advice of pharmacists or physicians (Eisenberg et al., 1998). This lack of professional supervision may expose the consumer to various risks, including those derived by interactions with conventional drugs (Abebe, 2002).

Herbal products are defined as “herbal preparations produced by subjecting herbal materials to extraction, fractionation, purification concentration, or other physical or biological processes. They may be produced for immediate consumption or as the basis for herbal products. Herbal products may contain excipients or inert ingredients, in addition to the active ingredients they are generally produced in larger quantities for the purpose of retail sales” (Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary, 2001). Despite the possible adverse effects and risk of interactions, people continue to use herbal medicines for a variety of reasons which may include general health maintenance, treatment of specific disease states and more frequently for chronic conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, headaches, pain and cancer) (Eisenberg et al., 1993,1998), or the desire to control their medical and health related decisions. Survey data from the United Kingdom showed that herbal medicines have been used by about 30 per cent of the British population (Thomas et al., 2001), whereas, results from a study conducted in the United States by the centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that 19 per cent of adults had used herbal products (Barnes et al., 2004). The out of pocket expenditure associated with the use of herbal medicines was estimated to amount to £31 million in the United Kingdom (Thomas et al., 2001) £1 billion in Germany (Marstedt and Moebius, 2000), and about $5.1 billion in the United States (Barnes et al., 2004).

Among health-care professionals, pharmacists are in an ideal position to provide evidence based information and to help consumers to make safe choices about natural compounds, because of their accessibility and the increasing sales of these products in pharmacies. Lately, however, their role in providing primary health care is changing. As underlined by some studies (Levy, 1999; Gül et al., 2007) consumers still consider pharmacists trustworthy and knowledgeable about herbs while in other situations consumers nowadays are better educated and have more access to information, so they no longer blindly accept the advice of pharmacists (Traulsen and Noerreslet, 2004; Kwan et al., 2008). So it is urgent to ensure that pharmacists are appropriately educated and trained. A recent study done in the US reported that pharmacists are now receiving more questions from patients regarding the use of natural products than ever before, which necessitate that pharmacists become knowledgeable about these products and on their uses, dosing, adverse effects, drug interactions and contraindications (Clauson et al., 2003). This increased use of herbal and complementary medicines, particularly herbal remedies and dietary supplements, makes it necessary for a pharmacist to keep himself updated with the current development in this area (Chang et al., 2000).

With the increased popularity of dietary supplements and herbal products, community pharmacists are likely facing an increased number of questions concerning these products, particularly since they often sell these products and are the health professionals most accessible to the consumer. This hypothesis is supported by a recent survey of Minnesota pharmacists, who reported a greater than threefold increase between 1996 and 2000 in the number of questions received concerning herbal and other natural products (Welna et al., 2003).

Despite the increased frequency of questions about dietary supplements and their availability in most community pharmacies, pharmacists appear to lack sufficient knowledge in this area (Nathan and Cicero, 2005). Studies reported that 44% of pharmacists surveyed acknowledged that their knowledge of herbs and natural products is not adequate (Welna et al., 2003). Similarly also surveyed various clinicians, including 46 pharmacists, about their knowledge of and attitude toward herbs and other dietary supplements. Pharmacists’ knowledge level score was less than 50% of the maximal score, and their score for the level of confidence in their clinical expertise when dealing with questions about herbs and dietary supplements was 30% of the maximal score (Kemper et al., 2003). Given these results, the author believes that pharmacists need to have resources available to them on herbal supplements to provide current, accurate, and unbiased information on these products.

The use of herbal remedies is very common in the Arab world and Saudi Arabia is no exception to it. Anecdotally, it is thought that herbal products are popular as a result of a widespread belief that the preparations are natural and therefore safe. Another notable practice in Saudi Arabia is the increased prevalence of self-medication, along with a concomitant use of herbal and conventional medicines. This is an area of great concern due to its potential for drug–herb interactions (Al Braik et al., 2008). Moreover, several incidents of adulteration of herbal medicines with drug active ingredients, poor product quality, side effects and drug interactions are also reported from the region (Saxena, 2003).

In Saudi Arabia herbal remedy is freely available to all residents through herbal remedy shops or from retail outlets. The only outlet that is under the ministry of health (MOH) control is pharmacies. Though substantial proportions of herbal medicines are registered with the MOH, a large number of unregistered herbal products is also dispensed from a wide range of outlets, other than pharmacies.

Despite the fact that, several studies were done to measure public interest toward the use of herbal products (Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, 2003), the attitudes and perception of the pharmacist toward these products have not been adequately addressed. To our knowledge nobody investigated the availability of herbal medicinal information resources at community pharmacies in Saudi Arabia, therefore, the main purpose of this study is to assess availability of the current and perceived resources that would be helpful in answering inquiries about herbal medicines at community pharmacy. Additionally, the study was designed to evaluate pharmacists’ attitudes toward herbal medicine, to investigate whether; pharmacists discuss herbal medicine use with the patients and to investigate perceived barriers that limit discussing with patients about herbal medicine use.

2. Methods

A cross-sectional survey of community pharmacists in the Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia was conducted over a period of 6 months from July through December 2011. Data collection was carried out using a structured self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed and developed from a review of the literature and previous studies relating to herbal medicines (Bacon, 1997; Chang et al., 2000; Naidu et al., 2005). The survey questions were pre-tested by a pharmacist with an extensive experience in herbal medicines. A draft of the questionnaire was piloted on a convenience of 20 practicing pharmacists to check for readability, understanding, question design and the length of the questionnaire. Based on the result of this pilot study the questionnaire was used with little modifications and the final questionnaire was sent to the participants through handling by face to face, mail or E-mail.

The survey questionnaire consisted of a brief introduction to the study and eleven questions. The questions consisted of close ended, multiple-choice, and fill-in short answers. The questionnaire was constructed to include two sections. The first section comprised demographic information on both age and employment status, and close ended questions about whether they received previous continuing education on herbal medicines, or accessed herbal information at practice settings, and whether they sold herbal medicines at their practice sites. The second section asked about the frequency at which herbal medications are discussed with patients, how often this information was recorded in the patients’ medical record in the pharmacy, what barriers may prevent this type of discussion, what resources are currently available at practice settings, and what perceived resources would be helpful in answering herbal inquires. Notably, gender is not included in the demographics where female pharmacists are not allowed to work in community pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. The term “herbal medicine or herbal medications” was used throughout the survey to exclude vitamin and mineral use, in addition to minimizing varying assumptions of what is meant by this term. The full list of the survey questions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The complete list of questions used in the survey.

| 1- Age |

| 2- Employment status |

| 3- Have you ever received any previous continuing education on herbal medications? |

| 4- Have you ever been accessed to herbal information at practice site? |

| 5- Do you sell any herbal medicines at practice site? |

| 6- How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? |

| 7- How often do you record herbal medicine use in pharmacy? |

| 8- If you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients, what is the nature of the discussion? |

| 9- What are the barriers that limit discussing herbal medicines with your patients? |

| 10- Which herbal medicinal resources are readily available in your pharmacy? |

| 11- Which of the following herbal medicinal resources would be helpful in caring for your patients? |

A stratified random sample of one thousand and seven hundred registered pharmacy practitioners all over the Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia were randomly chosen to respond to the survey. Community pharmacies in the Riyadh region were randomly selected for visits according to their geographical distribution (i.e., north, south, east, and west). The selection of facilities was done at random with a clear intention to include different areas of the Riyadh region. The questionnaire was followed up for a collection on a later date that ranged from one to seven weeks. Non-respondents were telephoned, emailed or visited to return their questionnaire. All returned usable questionnaires were completed anonymously.

The data from each of the returned questionnaires were coded and entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) which was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics include percentages; means and frequency distribution were calculated for each of the variables. Chi square test was used to find the correlation between qualitative variables at the 5% significance level. The statistical measure of agreement (kappa) was calculated for the same categorical variable. A p-value of less than 0.05 represents a significant difference.

3. Results

Only one thousand four hundred one pharmacists responded to the survey (response rate is 82.4%) with a completely answered questionnaire. The demographic characteristics of the respondents were summarized in Table 2. The mean age of the respondents was 30.37 years with a standard deviation of ±5.641 years. The majority of the respondents (72.8%) are employed full time while 27.2% work part time. More than half of survey respondents (62.6%) received previous continuing education on herbal medicines and 37.4% were not well in this regard. Around sixty five percent (65.6%) of the participated pharmacists were accessed for herbal information at their practice site while 76.1% of the respondents sold herbal medicine at their practice site.

Table 2.

Demographic data of participated pharmacists.

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean ± SD (30.37 ± 5.641) | |

| Employment | N = 1392 |

| Full-time | 1014 (72.8%) |

| Part time | 378 (27.2%) |

| Have you ever received any previous continuing education on herbal medications? | N = 1399 |

| Yes | 876 (62.6%) |

| No | 523 (37.4%) |

| Have you ever accessed herbal information at practice site? | N = 1387 |

| Yes | 910 (65.6%) |

| No | 477 (34.4%) |

| Do you sell any herbal medicines at practice site? | N = 1390 |

| Yes | 1058 (76.1%) |

| No | 332 (23.9%) |

| How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? | N = 1395 |

| Very often | 65 (4.7%) |

| Often | 229 (16.4%) |

| Sometimes | 833 (59.7%) |

| Rarely | 209 (15.0%) |

| Never | 59 (4.2%) |

| How often do you record herbal medicine use in pharmacy? | N = 1395 |

| Very often | 45 (3.2%) |

| Often | 259 (18.6%) |

| Sometimes | 677 (48.5%) |

| Rarely | 283 (20.3%) |

| Never | 131 (9.4%) |

| If you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients, the discussion is: | N = 1400 |

| Self-initiated | 291 (20.8%) |

| Patients-initiated conversation | 620 (44.3%) |

| One-time discussion | 201 (14.3%) |

| Ongoing discussion | 139 (9.9%) |

| Others | 41 (2.9%) |

| What are the barriers that limit discussing herbal medicines with your patients? | N = 1632a |

| Lack of time | 645 (46%) |

| Lack of reliable sources | 424 (30.3%) |

| Not interest in the subject | 128 (9.1%) |

| Lack of herbal knowledge | 188 (13.4%) |

| Lack of scientific evidence to support the use of herbal medicine | 213 (15.2%) |

| Others | 34 (2.4%) |

| Which herbal medicinal resources are readily available in your pharmacy? | N = 1851a |

| Books | 461 (32.9%) |

| Package inserts/Brochures | 546 (39%) |

| Internet web sites | 627 (44.8%) |

| Computer databases | 186 (13.3%) |

| Others | 31 (2.2%) |

| Which of the following herbal medicinal resources would be helpful in caring for your patients? | N = 2060a |

| Books | 538 (38.4%) |

| Package inserts/Brochures | 392 (28%) |

| Internet web sites | 665 (47.5%) |

| Computer databases | 200 (14.3%) |

| Consultation services by pharmacist | 244 (17.4%) |

| Others | 21 (1.5%) |

The total number exceeded 1401 and percentage exceeded 100 per cent because respondents can choose more than one answer.

The study results show that 59.7% of the participants sometimes discuss herbal medicine use with their patients, while only 4.25% never discuss it. Study shows 48.5% of participated pharmacists record herbal medicine use sometimes where only 9.4% of them never did so. However, with regard to the initiation of the discussion, the study shows that 44.3% of the respondents reported that patients initiate herbal issue discussion while 20.8% reported that the pharmacists initiate the discussion. This discussion was reported to be a one time discussion or an ongoing discussion by 14.3% or 9.9% of the respondents respectively. According to the study results, respondents reported that the most common barriers that limit discussing herbal medicine use with their patients were lack of time due to other obligations assigned to the community pharmacist (46%), lack of reliable resources (30.3%), lack of scientific evidence that supports herbal medicine use (15.2%), or lack of knowledge of herbal medicines (13.4%). Yet, a small number of respondents was concerned about the interest in herbal medicines (9.1%) and other reasons including lack of patient demand, poor communication skills, lack of privacy and inaccessibility of the pharmacists and lack of knowledge about the patient’s medical and medication histories and the pharmacist–physician relationship (2.4%).

Pharmacists who discussed herbal medicine use with their patients rely on various resources to answer inquiries and gather information pertaining to herbal medicines. Reliable herbal resources currently available with the respondent pharmacists at their practice sites are illustrated in Fig. 1. The findings in this study indicated that community pharmacists turn most greatly to Web sites (44.8%) to find information on herbal medicines followed by manufacturer-provided information such as package inserts and pamphlets or brochures (39%) and books (32.9%). Only a minority of respondents had access to computer database (13.3%) and other resources (2.2%).

Figure 1.

Reliable herbal resources currently available to the respondents at their practice sites.

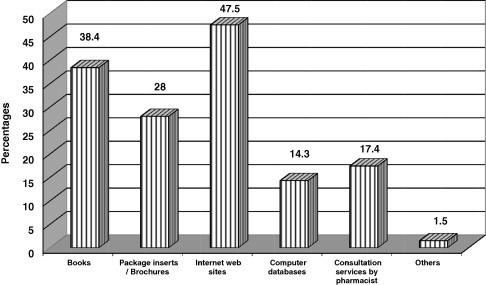

Generally, when respondents were asked about their favorite resource format that would be helpful in answering questions and advising their patients about herbal use, a majority of the pharmacists surveyed perceived Web sites (47.5%) and books (38.4%) (Fig. 2). These were followed by manufacturer-provided information (28%) and consultation services provided by the pharmacy (17.4%), while, others preferred computer database (14.3%) and other resources like journals, magazines, lectures and seminars (1.5%). The percentage exceeded 100 per cent because respondents can choose more than one answer.

Figure 2.

Favorable herbal medicinal resources to the respondents.

Additionally, the results show a significant correlation between accessibility of pharmacists to herbal information at practice sites to some variables including continuous education on, selling of, discussion with patients about the use of, and recording the use of, herbal medicine (p-values <0.05) (Table 3). Regarding the employment status, Table 4 shows no significant difference between the views of fulltime and part time employed pharmacists in relation to all measured parameters. Table 5 shows significant correlations (p-value >0.0001) and agreement (kappa coefficient = 0.28) between the answers of respondents about the use of herbal medicine and discussion of herbal medicine use with patients.

Table 3.

Pharmacist’s current practice with regard to herbal medicines.

| Have you ever been accessed to herbal information at practice site? |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Have you ever received any previous continuing education on herbal medicine? | |||

| Yes | 673 (74%) | 197 (41.3%) | |

| No | 237 (26%) | 280 (58.7%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Do you sell any herbal medicines at practice site? | |||

| Yes | 745 (82.7%) | 302 (63.3%) | |

| No | 156 (17.3%) | 175 (36.7%) | P < 0.0001 |

| How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? | |||

| Very often | 54 (5.9%) | 11 (2.3%) | |

| Often | 177 (19.5%) | 48 (10.1%) | |

| Sometimes | 554 (61.0%) | 271 (57.2%) | |

| Rarely | 109 (12.0%) | 99 (20.9%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Never | 14 (1.5%) | 45 (9.5%) | |

| How often do you record herbal medicine use in your pharmacy? | |||

| Very often | 32 (3.5%) | 13 (2.7%) | |

| Often | 199 (21.9%) | 59 (12.4%) | |

| Sometimes | 469 (51.7%) | 204 (42.9%) | |

| Rarely | 161 (17.7%) | 117 (24.6%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Never | 47 (5.2%) | 82 (17.3%) | |

| Do you sell any herbal medicines at practice site? |

|||

| Yes | No | ||

| How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? | |||

| Very often | 58(5.5%) | 7 (2.1%) | |

| Often | 191(18.1%) | 33 (10.0%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Sometimes | 671(63.7%) | 158 (47.7%) | |

| Rarely | 123(11.7% | 85 (25.7%) | |

| Never | 11(1.0%) | 48 (14.5%) | |

| How often do you record herbal medicine use in your pharmacy? | |||

| Very often | 41 (3.9%) | 4 (1.2% | |

| Often | 219 (20.8% | 38 (11.4%) | |

| Sometimes | 566 (53.8%) | 105 (31.6%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Rarely | 178 (16.9%) | 104 (31.3%) | |

| Never | 49 (4.7%) | 81 (24.4%) | |

| Have you ever received any previous continuing education on herbal medicine? |

|||

| Yes | No | ||

| Do you sell any herbal medicines at practice site? | |||

| Yes | 704 (81.1%) | 354 (67.8%) | P < 0.0001 |

| No | 164 (18.9%) | 168 (32.2%) | |

| How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? | |||

| Very often | 47 (5.4%) | 18 (3.4%) | |

| Often | 160 (18.3%) | 68 (13.0%) | |

| Sometimes | 534 (61.2%) | 299 (57.3%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Rarely | 112 (12.8%) | 97 (18.6%) | |

| Never | 19 (2.2%) | 40 (7.7%) | |

| How often do you record herbal medicine use in your pharmacy? | |||

| Very often | 34 (3.9%) | 11 (2.1%) | |

| Often | 184 (21.1%) | 75 (14.4%) | |

| Sometimes | 440 (50.5%) | 236 (45.2%) | P < 0.0001 |

| Rarely | 147 (16.9%) | 136 (26.1%) | |

| Never | 67 (7.7%) | 64 (12.3%) | |

Table 4.

Pharmacist response to herbal medicines on the basis of employment.

| Employment |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full time | Part time | ||

| Have you ever accessed herbal information at practice site? | |||

| Yes | 658 (65.5%) | 250 (66.7%) | 0.677 |

| No | 347 (34.5%) | 125 (33.3%) | |

| Have you ever received any previous continuing education on herbal? | |||

| Yes | 625 (61.6%) | 249 (65.9%) | 0.146 |

| No | 389 (38.4%) | 129 (34.1%) | |

| Do you sell any herbal medicines at practice site? | |||

| Yes | 780 (77.4%) | 274 (73.1%) | 0.094 |

| No | 228 (22.6%) | 101 (26.9%) | |

| How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? | |||

| Very often | 53 (5.2%) | 12 (3.2%) | 0.066 |

| Often | 175 (17.3%) | 52 (13.8%) | |

| Sometimes | 604 (59.7%) | 226 (59.9%) | |

| Rarely | 139 (13.7%) | 69 (18.3%) | |

| Never | 40 (4.0%) | 18 (4.8%) | |

| How often do you record herbal medicine use in your pharmacy? | |||

| Very often | 34 (3.4%) | 11 (2.9%) | 0.64 |

| Often | 185 (18.3%) | 74 (19.6%) | |

| Sometimes | 500 (49.5%) | 172 (45.6%) | |

| Rarely | 197 (19.5%) | 85 (22.5%) | |

| Never | 94 (9.3%) | 35 (9.3%) | |

Table 5.

Pharmacist response to use of herbal medicine in community pharmacy. Bold values represent p < 0.0001 in all fields.

| How often do you record herbal medicine use in your pharmacy? |

Symmetric measures |

P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very often | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Total | Spearman correlation | Kappa | ||

| How often do you discuss herbal medicine use with your patients? | |||||||||

| Very often | 16 | 22 | 18 | 6 | 3 | 65 | |||

| % of total | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.3% | 0.4% | 0.2 | 4.7% | |||

| Often | 12 | 106 | 88 | 19 | 4 | 229 | P < 0.0001 | ||

| % of total | (0.9%) | 7.6% | 6.3% | 1.4% | 0.3% | 16.5% | 0.461 | 0.28 | |

| Sometimes | 15 | 109 | 497 | 164 | 43 | 828 | |||

| % of total | 1.1% | 7.8% | 35.8% | 11.8% | 3.1% | 59.6% | |||

| Rarely | 2 | 20 | 64 | 84 | 39 | 209 | |||

| % of total | 0.1% | 1.4% | 4.6% | 6.0% | 2.8% | 15.0% | |||

| Never | 0 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 42 | 59 | |||

| % of total | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.6% | (3.00%) | 4.2% | |||

| Total | 45 | 259 | 673 | 282 | 131 | 1390 | |||

| % of total | 3.2% | 18.6% | 48.4% | 20.3% | 9.4% | 100.0% | |||

4. Discussion

Because Saudis have a strong belief in benefits of herbal products pharmacists experienced increased instances of counseling patients on this subject (Welna et al., 2003). The study reveals that herbal medicinal resources at community pharmacy in Saudi Arabia are reasonable enough. This finding is also consistent with the previous survey report, which revealed that Saudi nationals consider herbal products are more effective and safer for use than conventional medicine in different aspects (Al Braik et al., 2008). Additionally the current study revealed that about 76% of the participated pharmacists were dispensing herbal medicines from their community pharmacies, which rationalize the availability of herbal medicinal resources in community pharmacies in Saudi Arabia. It is therefore essential that pharmacists have more knowledge regarding different aspects of herbal products to be able to counsel patients regarding their use.

The study showed that frequent exposure to- and continuing education on herbal issues make the pharmacists more knowledgeable about herbal medicines which is consistent with other studies (Chang et al., 2000; Rickert et al., 1999). This necessitates the need for revising existing local pharmacy curricula to include courses on alternative medicines as reported in other studies (Clauson et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2000; Kouzi, 1996). Additionally, there is a need for the availability of more comprehensive herbal medicinal information resources.

One of the main roles of pharmacists is indeed to counsel the patients regarding their medications and it is all the more important for them to develop these skills to reinforce their existing role as the primary information provider to consumers. There is also an urgent need for the concerned regulatory bodies to identify a reliable source of drug information pertaining to herbal medications. This may be achieved by establishing drug information centers. It is no doubt that these efforts will facilitate provision of an enhanced and a comprehensive pharmaceutical care in Saudi Arabia.

Findings of this study indicates frequent exposure of community pharmacists to herbal issues which raised the importance of training toward reporting any suspected adverse drug events related to the use of herbal medicines to the concerned regulatory authority. The training should focus on the reporting mechanism and the need for information sharing regarding drug safety with all parties concerned including regulatory bodies to facilitate necessary corrective measures, as required. Appropriate educational activities may improve knowledge and awareness regarding herbal remedies. (Shields et al., 2004).

It is worth noting that the prevalence of chronic diseases is rapidly increasing in Saudi Arabia due to a number of factors including life style changes (Al-NOZha and et al., 2007). This has resulted in an expanding number of patients taking multiple medications, with consequently significant interactions when herbal remedies are also consumed (Koh et al., 2003). Therefore, this potential problem in drug therapy needs further attention by pharmacists if they are recommending these products to patients. In particular community pharmacists in Saudi Arabia need to be vigilant while questioning their patients regarding the use of herbal products with prescription medications. Patients should be well informed about possible side effects and be closely monitored. In order to achieve these goals, herbal medicinal information resources should be available in community pharmacies. Moreover, continuing education programs with more information on the safety and potential harmful effects of some herbal medicines should be provided to practicing pharmacists.

The results of the study revealed that an appreciable number of community pharmacists reported that they (often/very often or sometimes) discussed with their patients herbal medicine use and document this information. This may be due to frequent pharmacist exposure to inquiries about herbal remedies which are popularly used in Saudi Arabia. The overall documentation rates in this study (55.3%), are much higher than those reported in other studies which showed a physicians’ documentation rate ranging from 0% to 26% (Rivera et al., 2004; Leady et al., 2002), but is much lower than overall documentation rates observed in another study (Bouwmeester, 2005), which accounted for 78% who always and sometimes document herbal supplement use. The study population reported that they both discuss and record herbal medicine use for their patients despite the unavailability of enough knowledge about patients’ medical and medication histories and the absence of obligatory system that requires pharmacists to document this information. Such improvement in pharmacists’ documentation may be due to the implementation of clinical pharmacy and pharmaceutical care in pharmacy practice, which offers pharmacists an opportunity to document herbal and other patients’ medication information. However, Pharmacists can generally gather the information they need directly from patients or from their physicians or medical records.

Additionally, the study revealed a set of barriers that limit pharmacists from discussing herbal medicine use with their patients. The most important of these barriers are lack of time, lack of reliable resources, lack of scientific evidence that supports the use of herbal medicine and lack of knowledge on herbal medicine. Another factor that could appear to have smaller but yet considerable influence in limiting pharmacists from discussing herbal medicine use in this study was lack of interest in herbal medicine. These findings reinforced the findings of similar studies (Bouwmeester, 2005; Knapp, 1979; Gossel, 1980), that identified time, inadequate training, limited interest in herbal therapies, skill and scarcity of reliable resources as major barriers that limit pharmacists from discussing herbal medicine use with their patients. In spite of this fact however, few pharmacists in our study may be inhibited from providing herbal information to their patients due to lack of confidence or uncertainty in their knowledge base. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies, which showed that pharmacists are sometimes reluctant to become involved in patient counseling because of lack of confidence in their ability in patient counseling or uncertainty about their knowledge base (Knapp, 1979; Gossel, 1980).

Moreover, many studies of public’s perceptions, revealed that many other barriers exist that hindered the practice of counseling, but not tested in our study. Such barriers include lack of patient demand. negative attitudes of healthcare professionals toward counseling, poor communication skills, physical barriers such as lack of privacy and inaccessibility of the pharmacists and lack of knowledge about the patient’s medical and medication histories (Knapp, 1979; Gossel, 1980; Dutta et al., 2003; Ortiz and Thomas, 1985). Similarly, a factor that can lead to another barrier to patient counseling, is the pharmacist–physician relationship, however, although physicians are cautious about certain pharmacists’ activities that create areas of tension between them, physicians are generally willing to cooperate with pharmacists for the benefit of the patient (Ortiz and Thomas, 1985).

Although a part of the problem lies in the availability of reliable resources and knowledge, pharmacists also need education and formal training on herbal medicines and where to find herbal information and how to evaluate it to make a decisive decision before making recommendation and providing information for their patients. Several pharmacists commented that continuing education programs, conferences or seminar would be helpful in increasing their knowledge base in herbal medicines. Other suggested regular updates on the outcomes of clinical studies in herbal medicines and consensus statements summarizing the best current information on herbal medicine in the form of newsletters and database. Likewise, an overwhelming number of pharmacists and physicians agreed that education and training program on herbal medicines are useful for all medical staff.

Schools and colleges of pharmacy in the United States have begun responding to the demand for formal herbal and natural product education and training by adding more instructions on this topic and other complementary and alternative medicine therapies (Dutta et al., 2003). To obtain information on herbal medicine pharmacists in our study referred to numerous electronic resources such as Web sites and computer databases and certain periodicals. Although the survey was not designed to capture the type of Web sites and database used, nevertheless, there are several web sites and databases that are concerned with herbal and alternative medicines available either free or for subscription over the internet (Malone et al., 2001). For example, reference-style information resources as the Review of the Natural Products and Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database have the advantage of the ease of use for busy practitioners. Additionally, both databases offer regular, reasonably priced updates, which are an extremely vital feature since new information on herbal medicine is appearing rapidly (Jackson and Kanmaz, 2001). In general, it is valuable to evaluate the electronic resources before using them for reliability, accuracy, timeliness, reputability and depth of information (Bouwmeester, 2005). Furthermore, the survey showed that those who do not have access to the internet or other electronic databases frequently consult print resources. Reference books, package inserts, pamphlets and brochures were the print resources most frequently consulted in the survey. It is worthwhile noting that several evaluations of herbal reference books have been published and can serve as a good guide for healthcare professionals who desire print resources (Ortiz and Thomas, 1985; Shields et al., 2004; Sweet et al., 2003). One study reported that pharmacists counseled patients on herbal and natural products an average of 4.8 times per month – 3.1 times per month over the telephone and 5.3 times per month face-to-face, or approximately, an average of two times per week and few pharmacists (19%) reported receiving requests from physicians and other practitioners (Bouldin et al., 1999). While another study reported pharmacists counseled patients on herbal and natural products an average of seven times per week and significantly, more pharmacists (74%) reported receiving requests for herbal information from physicians and other practitioners (Welna et al., 2003).

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Frequent exposure of community pharmacists to herbal issues at community pharmacy settings necessitates that regulatory bodies in Saudi Arabia need to pay more attention to herbal medicinal resources at this setting. Additionally, extra efforts are needed to increase the awareness of pharmacists to adverse drug reactions reporting system at Saudi Food and Drug Authority. Finally, more consideration to herbal issues should be addressed in both pharmacy colleges’ curricula and continuous education program for pharmacists.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abebe W. Herbal medication: potential for adverse interactions with analgesic drugs. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002;27:391–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Braik F.A., Rutter P.M., Brown D. A cross-sectional survey of herbal remedy taking by United Arab Emirate (UAE) citizens in Abu Dhabi. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2008;17:725–732. doi: 10.1002/pds.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-NOZha M.M. Hypertenstion in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2007;28(1):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon M.M. University of Lowell; Lowell, MA: 1997. Nurse practitioners’ views and knowledge of herbal medicines and alternative healing methods. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P.M., Powell-Griner, E., McFann, K., Nahin, R.L., 2004. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no. 343, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. [PubMed]

- Bouldin A.S., Smith M.C., Gamer D.D. Pharmacy and herbal medicine in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999;49:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester C.J. Surveying physicians’ attitudes about herbal supplements, resources, and pharmacy consultations. J. Pharm. Technol. 2005;21(5):247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z.G., Kennedy D.T., Holdford D.A., Small R.E. Pharmacists’ knowledge and attitudes towards herbal medicines. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000;34:710–715. doi: 10.1345/aph.19263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z.G., Kennedy D.T., Holdford D.A. Pharmacists’ knowledge and attitudes towards herbal medicine. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000;34:710–715. doi: 10.1345/aph.19263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez M.L., Jordan M.A., Chavez P.I. Evidence-based drug herbal interactions. Life Sci. 2006;78:2146–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauson K.A., Mc-Queen C.E., Sheild K.M., Bryant P.J. Knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists in Missouri regarding natural products. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2003;67:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- De Smet P.A.G.M. Health risks of herbal remedies. Drug Saf. 1995;13:81–93. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199513020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act, 1994. Public law 103-417,103rd congress page. Food and Drug Administration Website. Available at <http://www.fda.gov/opacom/laws/dshea.html>. Ac.

- Dutta A.B., Daftary M.N., Egbe P.A. States of CAM education in U.S. schools of pharmacy: results of a national survey. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2003;43:81–83. doi: 10.1331/10865800360467105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D.M., Kessler R.C., Foster C. Unconventional medicine in the United States – prevalence, cost and pattern of use. New Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D.M., Davis R.B., Ettner S.L., Appel S., Wilkey S., Van Rompay M., Kessler R.C. Trends in alternative medicine use in the USA, 1990–1997; results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;289:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossel T.A. A pharmacist’s perspective on improving patient communication. Guidel. Prof. Pharm. 1980;7(3):4–5. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gül H., Omurtag G., Clark P., Tozan A., Ozel S. Nonprescription medication purchases and the role of pharmacists as healthcare workers in self-medication in Istanbul. Med. Sci. Monit. 2007;13:PH9–PH14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson E.A., Kanmaz T. An overview of information resources for herbal medicinal and dietary supplements. J. Herb. Pharmacother. 2001;1:35–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper K.J., Amata-Kynvi A., Dvorkin L. Herbs and other dietary supplements: healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2003;9(3):42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp D.A. Barriers faced by pharmacists when attempting to maximize their contribution to the society. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 1979;43(4):357–359. [Google Scholar]

- Koh H., Teo H., Ng H. Pharmacists pattern of use, knowledge, and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2003;9:51–63. doi: 10.1089/107555303321222946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzi S.A. Herbal remedies: the design of a new course in pharmacy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 1996;60:358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan D., Boon H.S., Hirschkorn K., Welsh S., Jurgens T., Eccott L., Heschuk S., Griener G.G., Cohen-Kohler J.C. Exploring consumer and pharmacist views on the professional role of the pharmacist with respect to natural health products: a study of focus groups. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2008;8:40–50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leady M.A., Wolsefer J.S., Sweet B.V. Survey of alternative supplement use within a hospitalized population. Hosp. Pharm. 2002;37:1295–1300. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. Legal Status of Traditional Medicine and Complementary/Alternative Medicine: a Worldwide Review. [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. Healthcare 2000’ reveals consumer view of R.Ph.s. Drug Topics. 1999;143:64. [Google Scholar]

- Malone P.M., Mosdell K.W., Kier K.L. McGraw Hill; New York: 2001. Drug Information: A Guide for Pharmacists. pp. 364–366, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Marstedt, G., Moebius, S., 2000. Inanspruchnahme altemativer Methooen in der Meclizin. Gesundheitserstartung des Bunds. 9, 1–37. Through: <http://bmj.bmjjoumals.com/cgi/content/full/327/>.

- Naidu S.J., Wilkinson J.M., Simpson M.D. Attitudes of Australian pharmacists toward complementary and alternative medicines. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005;39:1456–1461. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan J., Cicero L.T.K. Availability of and attitudes toward resources on alternative medicine products in the community pharmacy setting. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2005;45:734–739. doi: 10.1331/154434505774909715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic Research Center; Stockton, Calif: 2003. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz M., Thomas R. Attitudes of medical practitioners to community pharmacists giving medication advice to patients (Part 3) Australian J. Pharm. 1985;66(10):803–810. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert K., Martinez R.R., Martinez T.T. Pharmacist knowledge of common herbal preparations. Proc. West Pharmacol. 1999;42:12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J.O., Hughes H.W., Stuart A.G. Herbals and asthmatic usage patterns among a border population. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004;38:220–225. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A. How harmless are herbal remedies on human kidney. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2003;14(1):205–206. Downloaded from http://www.sjkdt.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields K.M., McQueen C.E., Bryant P.J. National survey of dietary supplement resources at drug information centers. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2004;44:36–40. doi: 10.1331/154434504322713219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields K.M., Mc-Queen C.E., Bryant P.J. National survey of dietary supplement resources at drug information center. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2004;44:36–40. doi: 10.1331/154434504322713219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet B.V., Gay W.E., Leady M.A. Usefulness of herbal and dietary supplement references. Ann. Pharmacother. 2003;37:494–499. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K.S., Nicoll J.P., Coleman P. Use and expenditure on complementary medicine in England: a population based survey. Complement Ther. Med. 2001;9:2–11. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traulsen J.M., Noerreslet M. The new consumer of medicine: the pharmacy technicians’ perspective. Pharm. World Sci. 2004;26:203–207. doi: 10.1023/b:phar.0000035883.44707.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welna E.M., Hadsall R.S., Schommer J.C. Pharmacists’ personal use, professional practice behaviors, and perceptions regarding herbal and other natural products. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2003;43:602–611. doi: 10.1331/154434503322452247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson E.M. Drug interactions between herbal and prescription medicines. Drug Saf. 2003;26:1075–1092. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffani S., Cuzzolin L., Benoni G. Herbal products: behaviors and beliefs among Italian women. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2006;15:354–359. doi: 10.1002/pds.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]