Abstract

The myostatin (MSTN) gene is a candidate to influence extreme longevity owing to its role in modulating muscle mass and sarcopenia and especially in inhibiting the main nutrient-sensing pathway involved in longevity, i.e. mammalian target of rapamycin. We compared allele/genotype distributions of the exonic MSTN variants K153R (rs1805086), E164K (rs35781413), I225T and P198A, in Spanish centenarians (cases, n = 156; 132 women, age range 100–111 years) and younger adults (controls, n = 384; 167 women, age <50 years). No subject of either group carried a mutant allele of the E164K, I225T or P198A variation. The frequency of the variant R allele was significantly higher in centenarians (7.1 %) than in controls (2.7 %) (P = 0.001). The odds ratio of being a centenarian if the subject had the R allele was 3.48 (95 % confidence interval 1.67–7.28, P = 0.001), compared to the control group, after adjusting for sex. The results were replicated in an Italian cohort (centenarians, n = 79 (40 women), age range 100–104 years; younger controls, n = 316 (155 women), age <50 years), where a higher frequency of the R allele in centenarians (7.6 %) compared to controls (3.0 %) (P = 0.004) was independently confirmed. Although more research is needed, the variant allele of the MSTN K153R polymorphism could be among the genetic contributors associated with exceptional longevity.

Keywords: Centenarians, MSTN, Genetics

Introduction

Human lifespan is a partly heritable phenotype, with some alleles contributing to ‘longevity assurance’, because they enhance the structure and function of the organism (Martin et al. 2007). As we age, we inevitably experience age-associated declines in the systems and organs that determine physical fitness, notably in the skeletal muscle tissue, i.e. sarcopenia. Accelerated age loss of muscle strength is associated with higher mortality risk (Metter et al. 2004; Ruiz et al. 2008); as such, genes potentially associated with higher preservation of muscle function at late life could be associated not only with healthy ageing and lower disability risk but also with longevity. One such candidate is the myostatin (MSTN or growth differentiation factor 8) gene (Huygens et al. 2004).

Myostatin is a skeletal muscle-specific secreted peptide that essentially modulates myoblast proliferation and thus muscle mass/strength (McPherron et al. 1997). Myostatin loss or inhibition has proven effective in ameliorating symptoms of weakness in several animal models of muscle injury, atrophy and disease (Benny Klimek et al. 2010; Bogdanovich et al. 2002; Lee and McPherron 2001; Liu et al. 2008; Morrison et al. 2009; Murphy et al. 2010; Qiao et al. 2009; Siriett et al. 2006; Tsuchida 2008; Wagner et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2007). Myostatin inhibition, as well as variations in the MSTN gene, can also have functional consequences in humans.

Myostatin inhibitors, such as MYO-029, have an adequate safety margin and are able to improve the muscle strength/function or muscle contractile properties in some patients with muscular dystrophy (Krivickas et al. 2009; Wagner et al. 2008). Of the identified MSTN variations in humans, the Lys(K)153Arg(R) polymorphism located in exon 2 (rs1805086, 2379 A>G replacement) is one candidate to influence skeletal muscle phenotypes (Ferrell et al. 1999). The Lys(K)153Arg(R) amino acid replacement is found within the active mature peptide of the myostatin protein; it could influence proteolytic processing with its pro-peptide or affinity to bind with the extracellular activin type II receptor (ActRIIB). The MSTN K153R polymorphism is thus a candidate to influence skeletal muscle phenotypes, included in old people (see Garatachea and Lucía (2013) for a recent review).

One of the most robust and well-studied improvements in longevity is caused by starvation and genetic down-regulation of a nutrient-sensing pathway, namely mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Fontana et al. 2010; Kenyon 2010). The mTOR pathway is an evolutionarily conserved nutrient-sensing pathway that adjusts metabolism and growth to amino acid availability, growth factors, energy status and stress (Fenton and Gout 2011; Sengupta et al. 2010). A number of studies have demonstrated that myostatin acts as a negative regulator of mTOR-directed signalling (Amirouche et al. 2009; Langley et al. 2002; Lipina et al. 2010; McFarlane et al. 2006; Rios et al. 2004; Sartori et al. 2009; Trendelenburg et al. 2009), which provides support for a potential role of myostatin inhibition in longevity. Myostatin deletion is in fact beneficial for bone density, insulin sensitivity and heart function in senescent mice (Morissette et al. 2009). Inhibition of the myostatin receptor ActRIIB increased survival (by 17 %) in myotubularin-deficient mice (Lawlor et al. 2011). An extension of lifespan (+30 %) was also observed after therapy with follistatin (a natural antagonist of myostatin) in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy (Rose et al. 2009).

Identifying candidate gene variants associated with longevity is possible by studying the genotype of centenarians (Martin et al. 2007). This group of people are the survival tail of population, with a lifespan of at least 15–20 years higher than the average westerner. Centenarians are also a model of healthy ageing, as the onset of disability in these individuals is generally delayed until they are well into their mid-90s (Christensen et al. 2008; Terry et al. 2008).

The main purpose of this study was to compare the allele and genotype frequency of the MSTN K153R polymorphism between Spanish centenarians (aged 100–111 years) and a group of healthy younger adults (controls, aged <50 years) of the same ethnic origin. We also genotyped the very infrequent MSTN exonic variants E164K (rs35781413), I225T and P198A, owing to the fact that they can also cause amino acid replacements in the gene product (myostatin) expressed in human skeletal muscle (Saunders et al. 2006). The results in the Spanish population were independently replicated in a sample of Italian centenarians. Based on the aforementioned studies, particularly those suggesting an inhibitor role of myostatin on the mTOR pathway, we hypothesised that the variant R allele of the MSTN K153R polymorphism could be more frequent in centenarians compared with the general population.

Methods

The study was designed and carried out in accordance with the recommendations for the human genotype–phenotype association studies recently published by the NCI-NHGRI Working Group on Replication in Association Studies (Chanock et al. 2007). These recommendations include among others the following items: indicating time period and location of subject recruitment, success rate for DNA acquisition, sample tracking methods and genotyping with a second technology in a second laboratory.

Participants

Written consent was obtained from each participant. The study protocol was approved by the corresponding institutional ethics committees (European University of Madrid, Spain and University of Pavia, Italy) and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for Human Research of 1974 (last modified in 2000).

Spanish cohort

All the Spanish participants were of the same Caucasian (Spanish) descent for ≥3 generations. The majority (~90 %) of them lived most of their lives and were born in the same areas of Spain (Meseta Castellana, ~600-m altitude). Inclusion criteria for the group of controls were (1) age ≤50 years, (2) free of any diagnosed cardiometabolic disease and (3) having no known family history of high longevity (90+ years). During years 2008–2009, we extracted genomic DNA from saliva samples of 387 individuals (170 women, 217 men). During 2009–2012, we obtained DNA from saliva samples in 172 centenarians of both genders (142 women, 30 men; age range 100–111 years) living mainly in nursing residencies of the Spanish central area (Meseta Castellana). This cohort included the oldest European individual (111 years) alive in June 2012 (http://www.grg.org/Adams/E.HTM) and ~9 % of the cohort was aged ≥105 years. The most prevalent diseases were osteoarthritis (67 %), hypertension (57 %), dementia (49 %) and cardiovascular disease (29 %). Two centenarians were free of any diagnosed disease.

We evaluated the centenarians’ cognitive ability with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975), as well as their independence/functional capacity with the Barthel Index. The latter is an instrument widely used to measure the capacity of a person for the execution of ten basic activities in daily life, obtaining a quantitative estimation of the subject’s level of independency (Collin et al. 1988; Mahoney and Barthel 1965). The sum score ranges from 0 (totally dependent) to 100 (totally independent).

Replication cohort

We sought an independent replication of the results obtained in the Spanish population in an unrelated Italian cohort. Two groups of Italian subjects born and living in Northern Italy were investigated: 79 healthy centenarians (40 women, 39 men; age range 100–104 years) and a control group of 316 healthy young subjects aged < 50 years (165 women, 151 men; age range 28–50 years). The participants’ ages were defined by the dates of birth as stated on identity cards. All patients and controls in the Italian cohort were Caucasian whites ascertained to be of Italian descent. The criterion ‘of Italian descent’ was met when an individual’s parents and four grandparents originated from Italy. The history of past and current diseases was accurately collected, checking the centenarians’ medical documentation and the current drug therapy. Italian centenarians did not have major age-related disease (i.e. severe cognitive impairment, clinically evident cancer, ischemic heart disease, renal insufficiency, severe physical impairment), although part of this group had decreased visual or auditory acuity. Therefore, all of the Italian centenarians were in good health relative to their very advanced age.

Genotype assessment

Spanish cohort

Genotyping was performed specifically for research purposes. The researchers in charge of genotyping were totally blinded to the participants’ identities, i.e. saliva samples were tracked solely with barcoding and personal identities were only made available to the main study researcher who was not involved in actual genotyping. In all the participants, we extracted genomic DNA from saliva samples. We used the classical phenol–chloroform DNA extraction protocol with alcoholic precipitation. Genomic DNA was resuspended in 50 μl Milli-Q H2O and stored at −20 °C.

In all samples (from both cases and controls’ groups), sequences corresponding to the E164K, I225T, K153R and P198A variants were amplified during 2009–2012 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the Genetics Laboratory of the European University of Madrid (Spain). The primers used were 5′-GAAAACCCAAATGTTGCTTC-3′ and 5′-TGTCTAGCTTATGAGCTTAGGG-3′. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min; 35 cycles at 95 °C for 1 min, 52 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

The resulting PCR products were genotyped by single-base extension (SBE) (Gonzalez-Freire et al. 2010). The primers used for E164K, I225T, K153R and P198A were 5′-CAAACACTGTTGTAGGAGTCT-3′, 5′-CTGAATCCAACTTAGGCA-3′, 5′-TTTAATACAATACAATAAAGTAGTAA-3′ and 5′-TTTTTTTTATCTCTGAAACTTGACATGAAC-3′, respectively. The PCR SBE conditions were 96 °C for 10 s, then 25 cycles at 50 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The resulting PCR products were detected in an ABI PRISM (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

To ensure proper internal control, for each genotype analysis, we used positive and negative controls from different DNA aliquots which were previously genotyped by the same method according to recent recommendations for replicating genotype–phenotype association studies (Chanock et al. 2007). All the analyses were performed by two experienced independent investigators who were blinded to subject data.

To ensure external validity of genotyping methods, the results of a subset of polymorphisms/samples should be corroborated in a second laboratory using a different method (Chanock et al. 2007). As such, genotyping (polymorphisms K153R and E164K) of the samples of 134 centenarians (78 % of total) was also performed in the genomics laboratory of Vall d’Hebron Hospital (Barcelona, Spain) during the spring of 2012 using a different methodology, i.e. custom-designed Taqman® SNP genotyping assays (assay ID: C___282184_30 for the K153R variant and assay ID: C__57828961_10 for the E164K variant) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). All samples were run in a 7.500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The analysis had pre-read and post-read steps of the plate consisting of 1 min at 60 °C, before and after the PCR cycle. The cycle conditions were 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 92 °C, and 1 min at 60 °C.

Replication cohort

In Italian participants, genomic DNA was purified from peripheral blood samples using the QiaAmp DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In order to obtain unlimited quantities of centenarians’ DNA for different genotyping projects, an in vitro immortalization of genomic DNA was performed by means of whole-genome amplification using a commercially available kit (GenomiPhi, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Genotyping of the K153R polymorphism was performed in the Italian cohort during November 2012. The procedure for detecting the K153R polymorphism was based on PCR amplification, restriction cleavage with BanII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and separation of the DNA fragments by electrophoresis, as previously described (Ferrell et al. 1999). For quality control, genotyping analyses were done blind with respect to centenarian/young control status, and a random 25 % of the samples were repeated. The concordance rate for duplicate genotyping was 100 %. Two investigators independently reviewed all results.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the PASW (v. 18.0 for Windows, Chicago), except for statistical power, which we calculated with the StatMate software, version 2.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) (Emanuele et al. 2010; Minoretti et al. 2006). We tested Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium using a χ2 test. Genotype/allele frequencies were compared among the two study groups (centenarians and controls) within each cohort (Spanish and Italians) using the χ2 test with α set at 0.05. We used logistic regression analysis to analyse the association between alleles and longevity within each of the two cohorts after adjusting for sex.

Results

Spanish cohort

The median (min, max) of the Barthel score in the centenarians’ group was 15 (0, 100) whereas the mean ± SD (min, max) of MMSE was 13 ± 10 (0, 32). Approximately 13 % of the centenarians were virtually independent during daily living without assistance from other persons, i.e. their Barthel score was ≥80 and their score in MMSE was >23 (Christensen et al. 2008). The highest Barthel and MMSE scores (95 and 28, respectively) corresponded to an individual aged 102 years.

Failure rate of genotyping (due in all cases to insufficient amount of DNA) was 3 of 387 (0.78 %) in controls and 16 of 172 (9.3 %) in centenarians with the SBE method (European University of Madrid) and 17 of 134 (12.7 %) with the Taqman method (Vall d’Hebron Hospital). Successfully genotyped samples of centenarians showed 100 % concordant results between the two laboratories. No subject carried a mutant allele of the E164K (rs35781413), I225T and P198A variations.

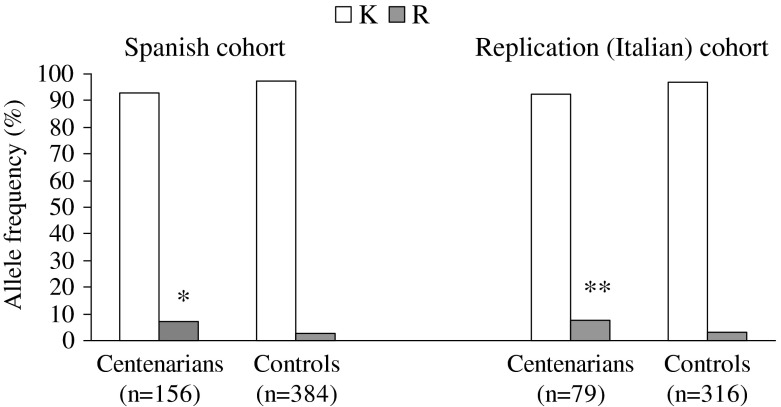

Genotype distributions of the MSTN K153R polymorphism met the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in both the control (P = 0.581) and the centenarian groups (P = 0.135). Figures 1 and 2 show the MSTN K153R allele and genotype frequencies respectively in the two study groups. The frequency of the R allele in the Spanish controls (~3 %) was similar to that previously reported in European Caucasians, i.e. 3–4 % with a frequency of mutant homozygotes (RR) below 1 % (Corsi et al. 2002; Ferrell et al. 1999; Kostek et al. 2009). The frequency of the variant R allele and of R allele carriers was significantly higher in centenarians (7.1 and 12.8 %) than in controls (2.7 and 5.5 %) (χ2 = 10.815, P = 0.001 and χ2 = 8.546, P = 0.003, respectively). Two centenarians had the very rare RR genotype (vs. no participant of the control group). The odds ratio (OR) of being a Spanish centenarian if the subject had the R allele was 3.48 (95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.67–7.28 P = 0.001), compared to the control group, after adjusting for sex.

Fig. 1.

Allele distribution of the MSTN K153R polymorphism in the Spanish and Italian cohorts. *P = 0.001, for Spanish centenarians vs. Spanish controls; **P = 0.004, for Italian centenarians vs. Italian controls

Fig. 2.

Genotype distribution of the MSTN K153R polymorphism in the Spanish and Italian cohorts. *P < 0.001, for the frequency of R allele carriers in Spanish centenarians vs. Spanish controls; **P = 0.008, for the frequency of R allele carriers in Italian centenarians vs. Italian controls

Italian cohort

There were no failures in sample collection, DNA acquisition or genotyping procedures for both centenarians and young controls. The genotype distributions of the MSTN K153R polymorphism met the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in both the control (P = 0.168) and the centenarian groups (P = 0.465). Figures 1 and 2 show the MSTN K153R allele and genotype frequencies respectively in the two study groups. In keeping with the results obtained in the Spanish cohort, the frequency of the R allele in Italian controls (3.0 %) was also similar to that previously reported in European Caucasians. The frequency of the variant R allele and of R allele carriers was significantly higher in centenarians (7.6 and 15.2 %) than in controls (3.0 and 5.7 %) (χ2 = 8.116, P = 0.004 and χ2 = 7.059, P = 0.008, respectively). No participant had the very rare RR genotype except one participant in the control group. The sex-adjusted OR of being an Italian centenarian if the subject had the R allele was 2.44 (95 %CI 1.19–5.21, P = 0.031), compared to the control group.

Statistical power

Based on the observed prevalence of the R allele of the K153R polymorphism in the combined cohorts (Spanish and Italian subjects), our sample size had an 80 % power to detect an OR of 1.92 for being a centenarian between R allele carriers and non-carriers with a significance level (α) of 0.05. Hence, the power calculations in the whole study sample imply that our data would have been sufficient to detect moderate (OR of 1.5–2.3) differences in allele and genotype frequencies between centenarians and controls.

Discussion

Our main finding was that the variant R allele of the MSTN K153R polymorphism is associated with exceptional longevity in the two independent cohorts we studied, with a significantly higher proportion of this allele in the group of centenarians (cases) compared with their controls. In fact, the frequency of the R allele in our centenarians (7.1 % in Spaniards and 7.6 % in Italians) was approximately twofold higher than that previously reported in the literature for European Caucasians, i.e. 3–4 % (Corsi et al. 2002; Ferrell et al. 1999; Kostek et al. 2009). Despite the complexity of the ageing process and the fact that exceptional longevity is likely a polygenic trait with numerous candidate genes exerting an effect either individually or in complex interactions, single-gene mutations (like maybe the one we studied here) may suffice to delay the onset of age-related phenotypes in a variety of model organisms, from yeast to mammals (Bjedov and Partridge 2011). There is a strong rationale for suggesting that myostatin inhibition, or alternatively mutations in the MSTN gene affecting its gene product, could contribute to exceptional longevity. Although more research is needed, the putative effects of the K153R variation, e.g. on muscle phenotypes, are due to its potential to alter the function of the MSTN gene (Ferrell et al. 1999). Indeed, the Lys(K)153Arg(R) amino acid replacement is found within the active mature peptide of the myostatin protein and could influence proteolytic processing with its pro-peptide or affinity to bind with the putative endogenous receptor for myostatin, ActRIIB (Jiang et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2005). The fact that the Lys(K)153Arg(R) substitution is conserved in all avian and mammalian species suggests that it might affect myostatin function (Ferrell et al. 1999).

The first mechanism by which myostatin inhibition or MSTN variations could affect longevity and healthy ageing is through an increase in muscle mass/function. In effect, myostatin is a skeletal muscle-specific secreted peptide that essentially modulates myoblast proliferation and thus muscle mass/strength (McPherron et al. 1997). Preclinical trials using myostatin loss or inhibition have been effective in ameliorating symptoms of weakness in several animal models of muscle injury, atrophy and disease (Benny Klimek et al. 2010; Bogdanovich et al. 2002; Lee and McPherron 2001; Liu et al. 2008; Morrison et al. 2009; Murphy et al. 2010; Qiao et al. 2009; Siriett et al. 2006; Tsuchida 2008; Wagner et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2007). In humans, myostatin inhibitors, such as MYO-029, have an adequate safety margin and are able to improve the muscle strength/function or muscle contractile properties in some patients with muscular dystrophy (Krivickas et al. 2009; Wagner et al. 2008). All these data are consistent with the growing interest in developing therapeutic inhibitors of myostatin for use in muscle-wasting disorders such as muscular dystrophy, cachexia or ageing-related sarcopenia (Tsuchida 2008) and with the fact that myostatin inhibition is proposed as a potential intervention for frailty and sarcopenia in the elderly (Swan 2011).

Variants of the MSTN gene are associated with muscle hypertrophy phenotypes in a range of mammalian species (Grobet et al. 1997; McPherron et al. 1997; McPherron and Lee 1997; Mosher et al. 2007). Myostatin expression increases might contribute to muscle wasting, as suggested by research in animal (immobilised mice) (Carlson et al. 1999) and human models, i.e. HIV infection (Gonzalez-Cadavid et al. 1998), critically ill patients (Constantin et al. 2011) or cachexia (Dasarathy et al. 2004). One study showed that serum myostatin levels increased with age, suggesting an association between myostatin and age-associated sarcopenia (Yarasheski et al. 2002). However, others have shown that myostatin expression does not increase (Kawada et al. 2001; Welle et al. 2002), and can even decrease (Baumann et al. 2003), in ageing-induced sarcopenia in humans or rodents, thus questioning its involvement in muscle mass wasting during ageing. In fact, the R allele has not been associated with higher muscle mass/function in old Caucasian people (aged <80 years) (see Garatachea and Lucía (2013) for a review). Carriage of one R allele does not seem to exert a major influence in the muscle phenotypes of non-agenarians (Gonzalez-Freire et al. 2010) whereas, surprisingly, the only two reported Caucasian old people with the RR genotype (i.e. a Spanish woman aged 96 years and an Italian person with assumed age <80 years) seemed to have lower muscle strength than their age-matched peers (Corsi et al. 2002; Gonzalez-Freire et al. 2010). Nonetheless, given the low frequency of the R allele, further research with larger population samples is needed to clearly elucidate its influence on muscle phenotypes and sarcopenia in very old people.

We believe that the stronger rationale to postulate a certain beneficial effect of the infrequent R allele on exceptional longevity is based on the inhibiting role that myostatin plays in the mTOR signalling pathway. Indeed, the most robust and well-studied improvements in ageing are caused by dietary restriction and also by genetic down-regulation of nutrient-sensing pathways, namely mTOR (Fontana et al. 2010; Kenyon 2010). The central component of the mTOR pathway, the TOR kinase, forms two functionally different complexes: TOR complex (TORC) 1 and TORC2, with TORC1 promoting growth by positively regulating S6 kinase (Fenton and Gout 2011) and TORC2 activating the pro-survival Akt kinase of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor signalling pathway (Cybulski and Hall 2009; Sparks and Guertin 2010). For instance, under starvation conditions, TORC1 is responsible for up-regulating autophagy, a process that generates energy by degrading portions of the cytoplasm (Neufeld 2010; Ravikumar et al. 2010). A number of studies have demonstrated that myostatin acts as a negative regulator of mTOR-directed signalling, which is consistent with its inhibitory effect on protein synthesis (Amirouche et al. 2009; Langley et al. 2002; Lipina et al. 2010; McFarlane et al. 2006; Rios et al. 2004; Sartori et al. 2009; Trendelenburg et al. 2009) and more specifically on protein translation in skeletal muscle (Trendelenburg et al. 2009). On the other hand, myostatin deletion is beneficial for bone density, insulin sensitivity and heart function in senescent mice (Morissette et al. 2009), and inhibition of ActRIIB, the cell membrane receptor for which myostatin has the highest affinity (Sakuma and Yamaguchi 2012), increases survival (by 17 %) in myotubularin-deficient mice, due to a delay in the point at which animals experience weight loss or complete hind limb paralysis (Lawlor et al. 2011) (X-linked myotubular myopathy is a severe form of congenital myopathy which most often manifests with severe perinatal weakness and respiratory failure). An extension of lifespan (+30 %) was also observed after therapy with follistatin (a natural antagonist of myostatin) in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy (Rose et al. 2009).

In summary, the variant R allele of the MSTN K153R polymorphism was significantly more frequent in centenarians than in the control group. Although more research is needed, this genetic variation could be among the genetic contributors associated with exceptional longevity.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS, ref. # PS09/00194).

Footnotes

Antoni L. Andreu and Alejandro Lucia share senior authorship.

References

- Amirouche A, Durieux AC, Banzet S, Koulmann N, Bonnefoy R, Mouret C, Bigard X, Peinnequin A, Freyssenet D. Down-regulation of Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in response to myostatin overexpression in skeletal muscle. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):286–294. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AP, Ibebunjo C, Grasser WA, Paralkar VM. Myostatin expression in age and denervation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2003;3(1):8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benny Klimek ME, Aydogdu T, Link MJ, Pons M, Koniaris LG, Zimmers TA. Acute inhibition of myostatin-family proteins preserves skeletal muscle in mouse models of cancer cachexia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391(3):1548–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov I, Partridge L. A longer and healthier life with TOR down-regulation: genetics and drugs. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39(2):460–465. doi: 10.1042/BST0390460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanovich S, Krag TO, Barton ER, Morris LD, Whittemore LA, Ahima RS, Khurana TS. Functional improvement of dystrophic muscle by myostatin blockade. Nature. 2002;420(6914):418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature01154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CJ, Booth FW, Gordon SE. Skeletal muscle myostatin mRNA expression is fiber-type specific and increases during hindlimb unloading. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(2 Pt 2):R601–606. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.2.r601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Hunter DJ, Thomas G, Hirschhorn JN, Abecasis G, Altshuler D, Bailey-Wilson JE, Brooks LD, Cardon LR, Daly M, Donnelly P, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Freimer NB, Gerhard DS, Gunter C, Guttmacher AE, Guyer MS, Harris EL, Hoh J, Hoover R, Kong CA, Merikangas KR, Morton CC, Palmer LJ, Phimister EG, Rice JP, Roberts J, Rotimi C, Tucker MA, Vogan KJ, Wacholder S, Wijsman EM, Winn DM, Collins FS. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447(7145):655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, McGue M, Petersen I, Jeune B, Vaupel JW. Exceptional longevity does not result in excessive levels of disability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(36):13274–13279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804931105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10(2):61–63. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin D, McCullough J, Mahajan RP, Greenhaff PL. Novel events in the molecular regulation of muscle mass in critically ill patients. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 15):3883–3895. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi AM, Ferrucci L, Gozzini A, Tanini A, Brandi ML. Myostatin polymorphisms and age-related sarcopenia in the Italian population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(8):1463. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulski N, Hall MN. TOR complex 2: a signaling pathway of its own. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(12):620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasarathy S, Dodig M, Muc SM, Kalhan SC, McCullough AJ. Skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with an increased expression of myostatin and impaired satellite cell function in the portacaval anastamosis rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287(6):G1124–1130. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00202.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuele E, Fontana JM, Minoretti P, Geroldi D. Preliminary evidence of a genetic association between chromosome 9p21.3 and human longevity. Rejuvenation research. 2010;13(1):23–26. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton TR, Gout IT. Functions and regulation of the 70 kDa ribosomal S6 kinases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43(1):47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell RE, Conte V, Lawrence EC, Roth SM, Hagberg JM, Hurley BF. Frequent sequence variation in the human myostatin (GDF8) gene as a marker for analysis of muscle-related phenotypes. Genomics. 1999;62(2):203–207. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span—from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328(5976):321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garatachea N, Lucía A (2013) Genes and the ageing muscle: a review on genetic association studies. Age (Dordr) 35(1):207–233. doi:10.1007/s11357-011-9327-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Cadavid NF, Taylor WE, Yarasheski K, Sinha-Hikim I, Ma K, Ezzat S, Shen R, Lalani R, Asa S, Mamita M, Nair G, Arver S, Bhasin S. Organization of the human myostatin gene and expression in healthy men and HIV-infected men with muscle wasting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(25):14938–14943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Freire M, Rodriguez-Romo G, Santiago C, Bustamante-Ara N, Yvert T, Gomez-Gallego F, Serra Rexach JA, Ruiz JR, Lucia A. The K153R variant in the myostatin gene and sarcopenia at the end of the human lifespan. Age. 2010;32(3):405–409. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9139-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobet L, Martin LJ, Poncelet D, Pirottin D, Brouwers B, Riquet J, Schoeberlein A, Dunner S, Menissier F, Massabanda J, Fries R, Hanset R, Georges M. A deletion in the bovine myostatin gene causes the double-muscled phenotype in cattle. Nat Genet. 1997;17(1):71–74. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huygens W, Thomis MA, Peeters MW, Aerssens J, Janssen R, Vlietinck RF, Beunen G. Linkage of myostatin pathway genes with knee strength in humans. Physiol Genom. 2004;17(3):264–270. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00224.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang MS, Liang LF, Wang S, Ratovitski T, Holmstrom J, Barker C, Stotish R. Characterization and identification of the inhibitory domain of GDF-8 propeptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315(3):525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada S, Tachi C, Ishii N. Content and localization of myostatin in mouse skeletal muscles during aging, mechanical unloading and reloading. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2001;22(8):627–633. doi: 10.1023/a:1016366409691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464(7288):504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostek MA, Angelopoulos TJ, Clarkson PM, Gordon PM, Moyna NM, Visich PS, Zoeller RF, Price TB, Seip RL, Thompson PD, Devaney JM, Gordish-Dressman H, Hoffman EP, Pescatello LS. Myostatin and follistatin polymorphisms interact with muscle phenotypes and ethnicity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(5):1063–1071. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivickas LS, Walsh R, Amato AA. Single muscle fiber contractile properties in adults with muscular dystrophy treated with MYO-029. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39(1):3–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley B, Thomas M, Bishop A, Sharma M, Gilmour S, Kambadur R. Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(51):49831–49840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor MW, Read BP, Edelstein R, Yang N, Pierson CR, Stein MJ, Wermer-Colan A, Buj-Bello A, Lachey JL, Seehra JS, Beggs AH. Inhibition of activin receptor type IIB increases strength and lifespan in myotubularin-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(2):784–793. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, McPherron AC. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(16):9306–9311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151270098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Reed LA, Davies MV, Girgenrath S, Goad ME, Tomkinson KN, Wright JF, Barker C, Ehrmantraut G, Holmstrom J, Trowell B, Gertz B, Jiang MS, Sebald SM, Matzuk M, Li E, Liang LF, Quattlebaum E, Stotish RL, Wolfman NM. Regulation of muscle growth by multiple ligands signaling through activin type II receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(50):18117–18122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505996102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipina C, Kendall H, McPherron AC, Taylor PM, Hundal HS. Mechanisms involved in the enhancement of mammalian target of rapamycin signalling and hypertrophy in skeletal muscle of myostatin-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(11):2403–2408. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CM, Yang Z, Liu CW, Wang R, Tien P, Dale R, Sun LQ. Myostatin antisense RNA-mediated muscle growth in normal and cancer cachexia mice. Gene Ther. 2008;15(3):155–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional Evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Bergman A, Barzilai N. Genetic determinants of human health span and life span: progress and new opportunities. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(7):e125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane C, Plummer E, Thomas M, Hennebry A, Ashby M, Ling N, Smith H, Sharma M, Kambadur R. Myostatin induces cachexia by activating the ubiquitin proteolytic system through an NF-kappaB-independent, FoxO1-dependent mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209(2):501–514. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lee SJ. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(23):12457–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387(6628):83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metter EJ, Talbot LA, Schrager M, Conwit RA. Arm-cranking muscle power and arm isometric muscle strength are independent predictors of all-cause mortality in men. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96(2):814–821. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00370.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoretti P, Gazzaruso C, Vito CD, Emanuele E, Bianchi M, Coen E, Reino M, Geroldi D. Effect of the functional toll-like receptor 4 Asp299Gly polymorphism on susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2006;391(3):147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette MR, Stricker JC, Rosenberg MA, Buranasombati C, Levitan EB, Mittleman MA, Rosenzweig A. Effects of myostatin deletion in aging mice. Aging cell. 2009;8(5):573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison BM, Lachey JL, Warsing LC, Ting BL, Pullen AE, Underwood KW, Kumar R, Sako D, Grinberg A, Wong V, Colantuoni E, Seehra JS, Wagner KR. A soluble activin type IIB receptor improves function in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 2009;217(2):258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DS, Quignon P, Bustamante CD, Sutter NB, Mellersh CS, Parker HG, Ostrander EA. A mutation in the myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs. PLoS genetics. 2007;3(5):e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KT, Ryall JG, Snell SM, Nair L, Koopman R, Krasney PA, Ibebunjo C, Holden KS, Loria PM, Salatto CT, Lynch GS. Antibody-directed myostatin inhibition improves diaphragm pathology in young but not adult dystrophic mdx mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(5):2425–2434. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld TP. TOR-dependent control of autophagy: biting the hand that feeds. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao C, Li J, Zheng H, Bogan J, Yuan Z, Zhang C, Bogan D, Kornegay J, Xiao X. Hydrodynamic limb vein injection of adeno-associated virus serotype 8 vector carrying canine myostatin propeptide gene into normal dogs enhances muscle growth. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, Massey DC, Menzies FM, Moreau K, Narayanan U, Renna M, Siddiqi FH, Underwood BR, Winslow AR, Rubinsztein DC. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(4):1383–1435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios R, Fernandez-Nocelos S, Carneiro I, Arce VM, Devesa J. Differential response to exogenous and endogenous myostatin in myoblasts suggests that myostatin acts as an autocrine factor in vivo. Endocrinology. 2004;145(6):2795–2803. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose FF, Jr, Mattis VB, Rindt H, Lorson CL. Delivery of recombinant follistatin lessens disease severity in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(6):997–1005. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JR, Sui X, Lobelo F, Morrow JR, Jr, Jackson AW, Sjostrom M, Blair SN. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. Sarcopenia and age-related endocrine function. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:127362. doi: 10.1155/2012/127362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori R, Milan G, Patron M, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Abraham R, Sandri M. Smad2 and 3 transcription factors control muscle mass in adulthood. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296(6):C1248–1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00104.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders MA, Good JM, Lawrence EC, Ferrell RE, Li WH, Nachman MW. Human adaptive evolution at myostatin (GDF8), a regulator of muscle growth. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(6):1089–1097. doi: 10.1086/509707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siriett V, Platt L, Salerno MS, Ling N, Kambadur R, Sharma M. Prolonged absence of myostatin reduces sarcopenia. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209(3):866–873. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks CA, Guertin DA. Targeting mTOR: prospects for mTOR complex 2 inhibitors in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2010;29(26):3733–3744. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan M. Meeting report: American Aging Association 40th Annual Meeting, Raleigh, North Carolina, June 3–6, 2011. Rejuvenation research. 2011;14(4):449–455. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry DF, Sebastiani P, Andersen SL, Perls TT. Disentangling the roles of disability and morbidity in survival to exceptional old age. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(3):277–283. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg AU, Meyer A, Rohner D, Boyle J, Hatakeyama S, Glass DJ. Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296(6):C1258–1270. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00105.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K. Myostatin inhibition by a follistatin-derived peptide ameliorates the pathophysiology of muscular dystrophy model mice. Acta Myol. 2008;27:14–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Fleckenstein JL, Amato AA, Barohn RJ, Bushby K, Escolar DM, Flanigan KM, Pestronk A, Tawil R, Wolfe GI, Eagle M, Florence JM, King WM, Pandya S, Straub V, Juneau P, Meyers K, Csimma C, Araujo T, Allen R, Parsons SA, Wozney JM, Lavallie ER, Mendell JR. A phase I/IItrial of MYO-029 in adult subjects with muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(5):561–571. doi: 10.1002/ana.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welle S, Bhatt K, Shah B, Thornton C. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and myostatin mRNA expression in muscle: comparison between 62–77 and 21–31 yr old men. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37(6):833–839. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarasheski KE, Bhasin S, Sinha-Hikim I, Pak-Loduca J, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Serum myostatin-immunoreactive protein is increased in 60–92 year old women and men with muscle wasting. J Nutr Health Aging. 2002;6(5):343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Li Y, Shen W, Qiao C, Ambrosio F, Lavasani M, Nozaki M, Branca MF, Huard J. Relationships between transforming growth factor-beta1, myostatin, and decorin: implications for skeletal muscle fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(35):25852–25863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]