Abstract

Objectives

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research funded three practice-based research networks (PBRNs), NW-PRECEDENT, PEARL and DPBRN to conduct studies relevant to practicing general dentists. These PBRNs collaborated to develop a questionnaire to assess the impact of network participation on changes in practice patterns. This report presents results from the initial administration of the questionnaire.

Methods

Questionnaires were administered to network dentists and a non-network reference group. Practice patterns including caries diagnosis and treatment, pulp cap materials, third molar extraction, dentin hypersensitivity treatments and endodontic treatment and restoration were assessed by network, years in practice, and level of network participation.Test-retest reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated.

Results

950 practitioners completed the questionnaire. Test-retest reliability was good-excellent (kappa>0.4) for most questions. Significant differences in responses by network were not observed. The use of caries risk assessment forms differed by both network participation (p<0.001) and years since dental degree (p=0.026). Recent dental graduates are more likely to recommend third molar removal for preventive reasons (p=0.003).

Conclusions

Practitioners in the CONDOR research networks are similar to their US colleagues. As a group, however, these practitioners show a more evidence-based approach to their practice. Dental PBRNs have the potential to improve the translation of evidence into daily practice. Designing methods to assess practice change and the associated factors is essential to addressing this important issue.

Keywords: dental practice-based research networks, behavior change, practice impact

INTRODUCTION

The ultimate goal of dental practice-based research networks (PBRNs) is to impact the practice of dentistry by improving patient care.1 Potentially, this can be accomplished through PBRNs if activities and findings of practice-based research can shorten the knowledge translational gap, estimated in biomedical research to be between 17-20 years.2 This translational gap – the time between identifying effective procedures or care protocols and the adoption and sustained use of that information in routine practice - consists of many barriers.3,4, 5 For example, it has been documented that passive dissemination of knowledge (i.e. solely through publications) is unlikely to substantially change professional behavior.6 More interactive strategies to engage clinicians in obtaining and integrating new information into their practices are critically needed. It has been suggested that the likelihood of translating research into practice would be higher if dentists were involved in research and if the research were relevant to their clinical practice and the well-being of their patients.7 The diversity of studies available in the research portfolio of a PBRN presents multiple opportunities to attract broad practitioner participation and provide ‘practice-based evidence’ most relevant to clinicians and enhance generalizability. In addition, group interaction, positive staff attitudes, inter-organizational collaboration, and networks have been identified as facilitators of research translation in dental practice.8

In 2005, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded three dental practice-based research networks (PBRNs) known as NW PRECEDENT, DPBRN, and PEARL.1,9 These PBRNs are known collectively as the Collaboration on Networked Dental and Oral Health Research (CONDOR). Northwest Practice-based Research Collaborative in Evidence-based Dentistry (NW PRECEDENT) consists of approximately 250 practitioners in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Utah.10 The Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN) is administered by the University of Alabama at Birmingham and includes over 1,100 dental practitioners mainly from five regions in the United States and Scandinavia.11 The Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning (PEARL) Network consists of almost 200 practitioners from 23 states, administered through New York University.12

This study represents a joint effort of the PBRNs that comprise CONDOR to develop a strategy for assessing the impact of practice-based dental research on the PBRN practices. The Practice-Impact Research Group (PIRG) of CONDOR developed a questionnaire to assess practice patterns in caries risk assessment and management, including use of special forms to assess caries risk, use of pulp cap materials, diagnosis and treatment of dentin hypersensitivity, endodontic treatment and restoration, and third molar extraction. This study presents data on dentists’ practices from the first administration of the questionnaire. Subsequent administrations will provide an opportunity to detect practice changes as results from PBRN studies are disseminated.

METHODS

Questionnaire Development

Each PBRN contributed questions to a questionnaire that represented topics under research investigation by the respective PBRN. The survey included questions on how respondents obtain information and on how that information influences their practice of dentistry. Responses to these latter questions are reported in a separate publication13. In total, the questionnaire included 16 items. The questionnaire was pre-tested for clarity and readability among all networks and revised accordingly. Questions related to methods used to diagnose primary caries lesions had been used in a prior survey conducted by the DPBRN14 The protocol for questionnaire content and administration was reviewed and approved by an independent panel advisory to the NIDCR and was approved or received a waiver from each Network IRB.

Survey Administration and Data Collection

Letters of invitation and route of questionnaire administration differed by network. The questionnaire was administered the same way (electronic or paper) at each administration within each PBRN. Because the questionnaire includes pictures of teeth with specific dental conditions, particular care was taken to assure adequate resolution of these pictures in paper or electronic questionnaires.

PEARL invited 186 Practitioner-Investigators (P-Is) to complete the questionnaire via a secure online application. The questionnaire was open for completion in April 2009 and follow-up with non-responders continued via e-mail, telephone, and facsimile until March 2010. The response rate was 79% (147 respondents). To measure test-retest reliability, the questionnaire was completed twice by 34 PEARL members between April 20 and April 25, prior to the opening session of the annual PEARL meeting. The median test-retest timeframe for data capture was 2 days (range 1-4 days); 75% of the participants completed the re-test within 3 days of the first administration.

DPBRN mailed printed questionnaires to 1,013 enrolled dentists who had provided descriptive practice-level data, and were either general dentists, pediatric dentists, or indicated they performed at least some restorative dentistry. Reminders were sent 2-3 times to non-responders at the discretion of each regional PI and according to local IRB approvals. In the US, 595 dentists responded (66% response rate) and 62 responded from Sweden (90% response rate). Only US respondents are included in the current analysis. To measure test-retest reliability, the questionnaire was completed twice by 18 DPBRN practitioners, who completed the second questionnaire a mean (S.D.) of 62.9 (30.1) days after the first questionnaire. Median time between administrations was 50 days and 75% of dentists completed the questionnaire 92 days after first completion.

NW-PRECEDENT invited 195 PIs via e-blast to complete the questionnaire via a secure online application. In addition, 59 “Friends” of PRECEDENT, were invited. Friends are practitioners who have expressed interest in practice-based research, but are not trained to participate in clinical studies. They participate in surveys such as the PIRG survey and receive network newsletters. The questionnaire was open for completion June 25, 2009 and follow-up with non-responders continued via e-mail, telephone, and facsimile for 4 weeks. In total, 208 dentists responded (82% response rate). To measure test-retest reliability, NW-PRECEDENT re-administered the survey to 17 randomly selected practitioners an average of 237 days after first administration; 25% completed it within 232 days of first administration, 75% within 246 days.

Statistical Methods

Eleven items from the PIRG questionnaire are included in this analysis. (See Appendix for full questionnaire.) All questions used a closed-ended, multiple response format. Question format included clinical scenarios with or without photographs, with response categories as behavior frequencies and/or materials or procedures.

Demographic variables were previously reported on network-specific enrollment forms. The level of a respondent's participation in network activities was constructed from tracking databases maintained by each Network Chairman's office, as follows:

Full participant: a fully trained practitioner who participated in one or more studies with patient recruitment.

Partial participant: a fully trained practitioner who had not participated in a study with patient recruitment, but may have attended one or more network meetings, and/or completed surveys.

Reference: an inactive network member who had not received training, and had not participated in studies or network meetings, e.g. “Friends of PRECEDENT”. Responses from this reference group are used for comparison to the responses of those participating in network studies in the present analysis as well as in follow-up administrations of the questionnaire.

Two survey questions presented pictures of molars with varying degrees of caries and choices for restorative treatments. Respondents were given 13 discrete options from which they could choose one or more responses. To simplify the analyses, these options were recoded as follows.15

No Treatment or Further Diagnoses: No treatment or further diagnoses (e.g. Diagnodent, explorer, or radiograph)

Preventive treatment only: In-office fluoride, nonprescription fluoride, prescription fluoride, sealant or chlorhexidine treatment

Minimally invasive treatment with or without preventive treatment: Minimal drilling and sealant, minimal drilling and preventive resin restoration, air abrasion and sealant or air abrasion and preventive resin restoration ± preventive treatment.

Restorative treatment with or without preventive treatment: Amalgam restoration, resin-based composite restoration or indirect restoration ± preventive treatment.

Summary statistics for demographic variables are presented overall and by network. Survey responses are presented overall; by years since first dental degree; and by overall level of participation in the PBRN as defined above.

All analyses presented here are considered exploratory. The sample size for the study was based on having adequate power to detect changes in responses on repeat administrations, which will be reported in future publications. Chi-square or Fishers Exact statistic, as appropriate, was used to compare categorical variables among comparison groups. Kappa statistics were used to describe the extent of change in response in the test-retest samples, with weighted kappas used for ordinal response categories. Responses with kappa values greater than 0.75 are considered to have excellent agreement between the two administrations, values between 0.4 and 0.75 have good agreement and values <0.4 have marginal agreement.16 SAS version 9.2 was used and all p-values are presented without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 950 practitioners from the US responded to this initial administration of the survey: 595 from DPBRN, 147 from PEARL and 208 from NW-PRECEDENT. The majority of the respondents were white (78%), non-Hispanic (97%), and male (81%) (Table 1). PEARL had a larger proportion of respondents with 26 or more years of experience (57%, compared to 33% overall), likely due to PEARL's initial participant criterion of 10 or more years practice experience. A total of 378 (40%) participated in at least one non-survey network study (i.e Full Participants). An additional 346 (36%) had previously completed a survey or attended at least one network meeting, (i.e. Partial Participants). The reference group included the remaining 226 respondents. PEARL had a higher percentage of Full Participants contribute to this survey (48%) compared to 35% among DPBRN respondents and 47% of PRECEDENT respondents. A greater proportion of women practitioners (33.9%) are among recent dental graduates compared to 12.6% among the most experienced group. (p=<.001; Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents by Network

| DPBRN (N=595) | PEARL (N=147) | PRECEDENT (N=208) | Overall (N=950) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | N | 522 | 147 | 189 | 858 |

| Male | 428 (82%) | 110 (75%) | 155 (82%) | 693 (81%) | |

| Female | 94 (18%) | 37 (25%) | 34 (18%) | 165 (19%) | |

| Race | White | 471 (79%) | 113 (77%) | 157 (75%) | 741 (78%) |

| Black | 23 (4%) | 9 (6%) | 3 (1%) | 35 (4%) | |

| Asian | 19 (3%) | 18 (12%) | 18 (9%) | 55 (6%) | |

| Native American | 2 (< 1%) | 2 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 10 (1%) | |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | |

| Other or mixed racial | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 7 (1%) | |

| Ethnicity | N | 519 | 140 | 158 | 817 |

| Not Hispanic | 506 (97%) | 130 (93%) | 154 (97%) | 790 (97%) | |

| Hispanic | 13 (3%) | 10 (7%) | 4 (3%) | 27 (3%) | |

| Years since first post baccalaureate dental degree | N | 494 | 147 | 189 | 830 |

| 5 or fewer | 76 (15%) | 4 (3%) | 32 (17%) | 112 (13%) | |

| 6 - 15 | 103 (21%) | 24 (16%) | 50 (26%) | 177 (21%) | |

| 16 - 20 | 76 (15%) | 11 (7%) | 21 (11%) | 108 (13%) | |

| 21 - 25 | 94 (19%) | 24 (16%) | 37 (20%) | 155 (19%) | |

| 26+ | 145 (29%) | 84 (57%) | 49 (26%) | 278 (33%) | |

| Global level of involvement | N | 595 | 147 | 208 | 950 |

| Full participant | 209 (35%) | 71 (48%) | 98 (47%) | 378 (40%) | |

| Partial participant | 239 (40%) | 47 (32%) | 60 (29%) | 346 (36%) | |

| Control(Inactive or outside network) | 147 (25%) | 29 (20%) | 50 (24%) | 226 (24%) |

* Full participant: respondent has participated in at least one network study recruiting patients

Partial participant: respondent is a fully trained member of the network or has attended at least one meeting or participated in other survey studies

Reference: inactive member of the network (not trained, no participation in studies or meetings) or is outside the network, e.g. Friends of PRECEDENT

Table 2.

Demographics by Years Since First Dental Degree

| ≤ 5 (N=112) | 6 -15 (N=177) | >15 (N=541) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | N | 112 | 177 | 541 | <.001 |

| Male | 74 (66%) | 120 (68%) | 473 (87%) | ||

| Female | 38 (34%) | 57 (32%) | 68 (13%) | ||

| Race | White | 92 (82%) | 138 (78%) | 484 (89%) | |

| Black | 3 (3%) | 7 (4%) | 24 (4%) | ||

| Asian | 12 (11%) | 30 (17%) | 13 (2%) | ||

| Native American | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (< 1%) | ||

| Other or mixed racial | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (1%) | ||

| Ethnicity | N | 108 | 172 | 509 | 0.376 |

| Not Hispanic | 103 (95%) | 164 (95%) | 495 (97%) | ||

| Hispanic | 5 (5%) | 8 (5%) | 14 (3%) | ||

| Global level of involvement | N | 112 | 177 | 541 | 0.381 |

| Full participant | 44 (39%) | 71 (40%) | 251 (46%) | ||

| Partial participant | 50 (45%) | 72 (41%) | 198 (37%) | ||

| Control(Inactive or outside network) | 18 (16%) | 34 (19%) | 92 (17%) |

*Full participant: respondent has participated in at least one network study recruiting patients

Partial participant: respondent is a fully trained member of the network or has attended at least one meeting or participated in other survey studies

Reference: inactive member of the network (not trained, no participation in studies or meetings) or is outside the network, e.g. Friends of PRECEDENT

Test-Retest Reliability

Test-retest reliability was assessed separately by network. Among PEARL respondents there was good to excellent agreement (kappa = 0.41 – 0.91) between responses for all but two questions: question 11 regarding use of fluoride containing materials to treat dentin hypersensitivity (kappa = 0.09) and use of toothpaste or rinse to treat dentin hypersensitivity (kappa = 0.10). Among NW PRECEDENT there was marginal to excellent agreement (kappa=0.34 – 0.77) on all but question 11 (kappa=0.22), similar to PEARL. For DPBRN, agreement was good to excellent (kappa=0.44 - 0.95) on all questions except the option for use of chemical treatment (e.g. potassium nitrate) for dentin hypersensitivity (kappa = 0.22).

Caries Diagnosis and Treatment

The majority of respondents (59%) always use a dental explorer to diagnose primary occlusal caries lesions (Table 3); most (78%) use air-drying at least 50% of the time. Fewer full participants use a dental explorer all of the time (53%) compared to the others (p=0.04, Table 4). A majority (83%) report assessment of caries risk for individual patients, but only 23% use a special form for assessment. Among those who assess caries risk, more full participants use a specific form (32%) compared to partial participants (18%) or the reference group (13%) (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Survey Responses Overall and by Years Since First Dental Degree

| Overall US (N=830) | ≤ 5 (N=112) | 6 -15 (N=177) | >15 (N=541) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caries Diagnosis and Treatment | ||||||

| 1. When you examine patients to determine if they have a primary occlusal caries lesion, on what percentage of these patients do you use a dental explorer to help diagnose the lesion? | N | 829 | 111 | 177 | 541 | 0.135 |

| Never | 4 (< 1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | ||

| < 50% | 75 (9%) | 15 (14%) | 22 (12%) | 38 (7%) | ||

| 50-99% | 270 (33%) | 36 (32%) | 59 (33%) | 175 (32%) | ||

| Every time | 480 (58%) | 59 (53%) | 96 (54%) | 325 (60%) | ||

| 2. When you examine patients to determine if they have a primary caries lesion, on what percent of these patients do you use air-drying to help diagnose the lesion? | N | 829 | 112 | 176 | 541 | 0.725 |

| Never | 14 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 11 (2%) | ||

| < 50% | 175 (21%) | 24 (21%) | 41 (23%) | 110 (20%) | ||

| 50-99% | 391 (47%) | 49 (44%) | 87 (49%) | 255 (47%) | ||

| Every time | 249 (30%) | 38 (34%) | 46 (26%) | 165 (30%) | ||

| a. If you air-dry at least some, approximately how long do you dry the tooth surface? | N | 812 | 111 | 174 | 527 | 0.039 |

| 1 to 2 seconds | 344 (42%) | 54 (49%) | 66 (38%) | 224 (43%) | ||

| 3 to 4 seconds | 365 (45%) | 52 (47%) | 79 (45%) | 234 (44%) | ||

| 5+ seconds | 103 (13%) | 5 (5%) | 29 (17%) | 69 (13%) | ||

| 3. Do you assess caries risk for individual patients in any way? | N | 791 | 103 | 170 | 518 | 0.069 |

| Yes | 661 (84%) | 88 (85%) | 151 (89%) | 422 (81%) | ||

| No | 130 (16%) | 15 (15%) | 19 (11%) | 96 (19%) | ||

| a. If YES: | N | 639 | 87 | 147 | 405 | 0.026 |

| Record the assessment on a special form that is kept in the patient chart | 159 (25%) | 29 (33%) | 43 (29%) | 87 (21%) | ||

| Do not use a special form to make the assessment | 480 (75%) | 58 (67%) | 104 (71%) | 318 (79%) | ||

| 12. Do you use any in-office tests to assess caries risk? | N | 814 | 109 | 175 | 530 | <.001 |

| Yes | 146 (18%) | 20 (18%) | 48 (27%) | 78 (15%) | ||

| No | 668 (82%) | 89 (82%) | 127 (73%) | 452 (85%) | ||

| 7. Upon opening the tooth and during excavation of the caries you realize that the lesion is deeper than anticipated and may invovle the mesial buccal pulp horn. You would usally | N | 812 | 111 | 176 | 525 | 0.039 |

| Continue and remove all the decay | 372 (46%) | 51 (46%) | 73 (41%) | 248 (47%) | ||

| Stop removing decay near the pulp horn and remove it elsewhere | 285 (35%) | 45 (41%) | 56 (32%) | 184 (35%) | ||

| Temporize and treat or refer the tooth for endodontics | 155 (19%) | 15 (14%) | 47 (27%) | 93 (18%) | ||

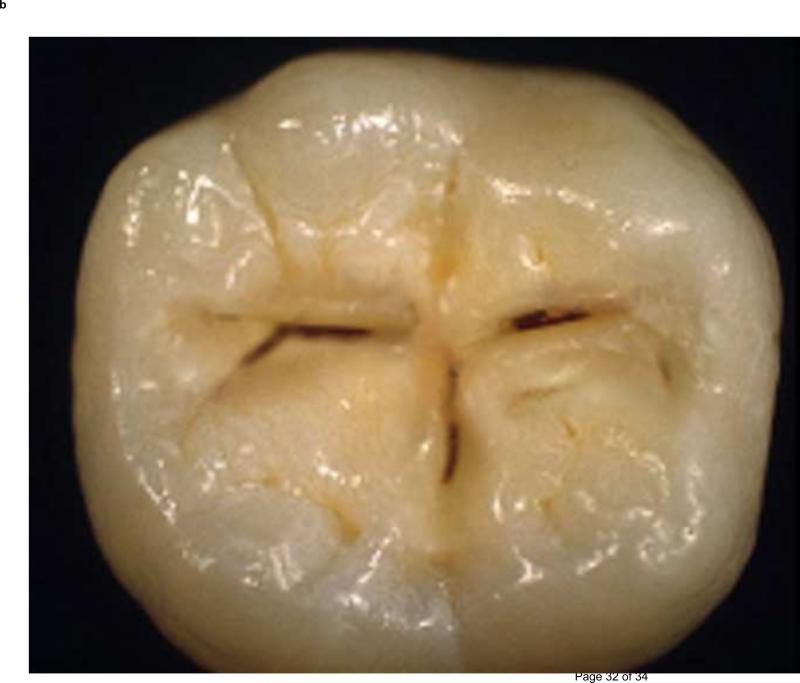

| Caries Treatment (see Figure 1 & 2) | ||||||

| 4. How would you treat the tooth shown above? | N | 830 | 112 | 177 | 541 | 0.291 |

| No Treatment or Further Diagnosis | 237 (29%) | 27 (24%) | 42 (24%) | 168 (31%) | ||

| Preventive only | 172 (21%) | 29 (26%) | 40 (23%) | 103 (19%) | ||

| Minimally invasive ± preventive | 293 (35%) | 40 (36%) | 68 (38%) | 185 (34%) | ||

| Restoration ± preventive | 118 (14%) | 13 (12%) | 26 (15%) | 79 (15%) | ||

| Other | 10 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| 5. How would you treat the tooth shown above? | N | 830 | 112 | 177 | 541 | 0.259 |

| No Treatment or Further Diagnosis | 105 (13%) | 10 (9%) | 19 (11%) | 76 (14%) | ||

| Preventive only | 81 (10%) | 14 (3%) | 19 (11%) | 48 (9%) | ||

| Minimally invasive ± preventive | 321 (39%) | 54 (48%) | 66 (37%) | 201 (37%) | ||

| Restoration ± preventive | 315 (38%) | 33 (29%) | 72 (41%) | 210 (39%) | ||

| Other | 8 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Pulp Capping | ||||||

| 8. Which of the following pulp capping materials do you use most often in your practice (choose one)? | N | 810 | 108 | 172 | 530 | <.001 |

| Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA) | 34 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 7 (4%) | 20 (4%) | ||

| Calcium Hydroxide | 393 (49%) | 43 (40%) | 76 (44%) | 274 (52%) | ||

| Glass Ionomer | 274 (34%) | 50 (46%) | 73 (42%) | 151 (28%) | ||

| Dentine Bonding System | 71 (9%) | 3 (3%) | 11 (6%) | 57 (11%) | ||

| Other | 38 (5%) | 5 (5%) | 5 (3%) | 28 (5%) | ||

| Third Molars | ||||||

| 9. What percentage of your patients do you refer for third molar extraction by the age of 20? | N | 759 | 100 | 163 | 496 | 0.320 |

| < 20% | 96 (13%) | 11 (11%) | 13 (8%) | 72 (15%) | ||

| 20-40% | 113 (15%) | 12 (12%) | 26 (16%) | 75 (15%) | ||

| 40-60% | 171 (23%) | 21 (21%) | 45 (28%) | 105 (21%) | ||

| 60-80% | 195 (26%) | 32 (32%) | 40 (25%) | 123 (25%) | ||

| > 80% | 184 (24%) | 24 (24%) | 39 (24%) | 121 (24%) | ||

| 10. Which statement best describes your philosophy on third molar referrals? | N | 820 | 109 | 175 | 536 | 0.003 |

| Recommend removal of most third molars for preventive reasons | 120 (15%) | 27 (25%) | 32 (18%) | 61 (11%) | ||

| Recommend removal if they have poor eruption path or do not have sufficient space for eruption | 598 (73%) | 70 (64%) | 120 (69%) | 408 (76%) | ||

| Recommend removal if a patient presents with symptoms or pathology associated with 3rd molars | 102 (12%) | 12 (11%) | 23 (13%) | 67 (13%) | ||

| Dentin Hypersensitivity | ||||||

| 11. What type of dentin hypersensivity treatments do you rountinely use or recommend for your patients? (check all that you use) | ||||||

| a. Dentin bonding agents | 543 (65%) | 63 (56%) | 109 (62%) | 371 (69%) | 0.021 | |

| b. Oxalate or bioglass containing material | 132 (16%) | 8 (7%) | 21 (12%) | 103 (19%) | 0.002 | |

| c. Fluoride containing material | 711 (86%) | 94 (84%) | 156 (88%) | 461 (85%) | ||

| d. Chemical treatment (e.g. potassium nitrate) | 343 (41%) | 35 (31%) | 80 (45%) | 228 (42%) | ||

| e. Toothpaste or rinse | 663 (80%) | 78 (70%) | 143 (81%) | 442 (82%) | ||

| f. Other | 86 (10%) | 12 (11%) | 18 (10%) | 56 (10%) | ||

| Endodontic Treatment | ||||||

| 13. One of your regular patients presents with pain in tooth #13. Upon clinical inspection the lingual cusp has fractured to just below the gingival margin and there is extensive decay beneath the large MOD composite restoration. | ||||||

| You are able to diagnose a condition of irreversible pulpitis but there is no radiographic evidence of periapical pathosis. You would at this point recommend to your patient that you: | N | 812 | 110 | 175 | 527 | 0.943 |

| Initiate endodontic treatment leading to placement of a post and core followed by a full crown | 526 (65%) | 71 (65%) | 116 (66%) | 339 (64%) | ||

| Extirpate pulp, temporize, refer for endodontic treatment and place a post, core and full crown | 174 (21%) | 24 (22%) | 31 (18%) | 119 (23%) | ||

| Extract tooth and place an immediate implant fixture and later restore with a crown | 34 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 8 (5%) | 22 (4%) | ||

| Extirpate pulp, temporize, refer for extraction and placement of implant, and restore with crown | 38 (5%) | 6 (5%) | 9 (5%) | 23 (4%) | ||

| Extract tooth, refer patient for placement of an implant ficture, and restore with crown | 40 (5%) | 5 (5%) | 11 (6%) | 24 (5%) |

Note: 120 respondents did not provide information about number of years since first dental degree. Overall reflects all US respondents.

Table 4.

Survey Responses by Global Level of Involvement

| Full participant1 (N=378) | Partial participant2 (N=346) | Reference3 (N=226) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caries Diagnosis and Treatment | |||||

| 1. When you examine patients to determine if they have a primary occlusal caries lesion, on what percentage of these patients do you use a dental explorer to help diagnose the lesion? | N | 377 | 345 | 225 | 0.042 |

| Never | 5 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| < 50% | 41 (11%) | 25 (7%) | 17 (8%) | ||

| 50-99% | 131 (35%) | 102 (30%) | 70 (31%) | ||

| Every time | 200 (53%) | 217 (63%) | 138 (61%) | ||

| 2. When you examine patients to determine if they have a primary caries lesion, on what percent of these patients do you use air-drying to help diagnose the lesion? | N | 378 | 344 | 225 | 0.002 |

| Never | 11 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (2%) | ||

| < 50% | 92 (24%) | 67 (19%) | 39 (17%) | ||

| 50-99% | 175 (46%) | 155 (45%) | 119 (53%) | ||

| Every time | 100 (26%) | 122 (35%) | 63 (28%) | ||

| a. If you air-dry at least some, approximately how long do you dry the tooth surface? | N | 367 | 341 | 220 | 0.888 |

| 1 to 2 seconds | 159 (43%) | 145 (43%) | 88 (40%) | ||

| 3 to 4 seconds | 162 (44%) | 147 (43%) | 102 (46%) | ||

| 5+ seconds | 46 (13%) | 49 (14%) | 30 (14%) | ||

| 3. Do you assess caries risk for individual patients in any way? | N | 365 | 322 | 217 | 0.096 |

| Yes | 307 (84%) | 276 (86%) | 171 (79%) | ||

| No | 58 (16%) | 46 (14%) | 46 (21%) | ||

| a. If YES: | N | 299 | 264 | 164 | <.001 |

| Record the assessment on a special form that is kept in the patient chart | 95 (32%) | 48 (18%) | 22 (13%) | ||

| Do not use a special form to make the assessment | 204 (68%) | 216 (82%) | 142 (87%) | ||

| 12. Do you use any in-office tests to assess caries risk? | N | 373 | 338 | 222 | 0.922 |

| Yes | 67 (18%) | 57 (17%) | 38 (17%) | ||

| No | 306 (82%) | 281 (83%) | 184 (83%) | ||

| 7. Upon opening the tooth and during excavation of the caries you realize that the lesion is deeper than anticipated and may invovle the mesial buccal pulp horn. You would usally | N | 374 | 336 | 220 | 0.097 |

| Continue and remove all the decay | 169 (45%) | 158 (47%) | 102 (46%) | ||

| Stop removing decay near the pulp horn and remove it elsewhere | 144 (39%) | 108 (32%) | 66 (30%) | ||

| Temporize and treat or refer the tooth for endodontics | 61 (16%) | 70 (21%) | 52 (24%) | ||

| Caries Treatment (See Figures 1 & 2) | |||||

| 4. How would you treat the tooth shown above? | N | 378 | 346 | 226 | 0.006 |

| No Treatment or Further Diagnosis | 109 (29%) | 102 (29%) | 68 (30%) | ||

| Preventive only | 92 (24%) | 59 (17%) | 39 (17%) | ||

| Minimally invasive ± preventive | 135 (36%) | 117 (34%) | 85 (38%) | ||

| Restoration ± preventive | 39 (10%) | 64 (18%) | 27 (12%) | ||

| Other | 3 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 7 (3%) | ||

| 5. How would you treat the tooth shown above? | N | 378 | 346 | 226 | 0.055 |

| No Treatment or Further Diagnosis | 50 (13%) | 44 (13%) | 35 (15%) | ||

| Preventive only | 48 (13%) | 24 (7%) | 22 (10%) | ||

| Minimally invasive ± preventive | 153 (40%) | 132 (38%) | 83 (37%) | ||

| Restoration ± preventive | 124 (33%) | 144 (42%) | 81 (36%) | ||

| Other | 3 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 5 (2%) | ||

| Pulp Capping | |||||

| 8. Which of the following pulp capping materials do you use most often in your practice (choose one)? | N | 371 | 336 | 217 | 0.832 |

| Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA) | 20 (5%) | 10 (3%) | 8 (4%) | ||

| Calcium Hydroxide | 177 (48%) | 165 (49%) | 112 (52%) | ||

| Glass Ionomer | 122 (33%) | 114 (34%) | 65 (30%) | ||

| Dentine Bonding System | 32 (9%) | 31 (9%) | 22 (10%) | ||

| Other | 20 (5%) | 16 (5%) | 10 (5%) | ||

| Third Molars | |||||

| 9. What percentage of your patients do you refer for third molar extraction by the age of 20? | N | 375 | 341 | 224 | 0.161 |

| < 20% | 45 (12%) | 35 (10%) | 30 (13%) | ||

| 20-40% | 55 (15%) | 48 (14%) | 20 (9%) | ||

| 40-60% | 92 (25%) | 62 (18%) | 42 (19%) | ||

| 60-80% | 83 (22%) | 82 (24%) | 60 (27%) | ||

| > 80% | 70 (19%) | 89 (26%) | 53 (24%) | ||

| No pediatric patients | 3 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 4 (2%) | ||

| Cannot provide a meaningful estimate | 27 (7%) | 20 (6%) | 15 (7%) | ||

| 10. Which statement best describes your philosophy on third molar referrals? | N | 374 | 339 | 223 | 0.558 |

| Recommend removal of most third molars for preventive reasons | 47 (13%) | 53 (16%) | 30 (13%) | ||

| Recommend removal if they have poor eruption path or do not have sufficient space for eruption | 276 (74%) | 250 (74%) | 169 (76%) | ||

| Recommend removal if a patient presents with symptoms or pathology associated with 3rd molars | 51 (14%) | 36 (11%) | 24 (11%) | ||

| Dentin Hypersensitivity | |||||

| 11. What type of dentin hypersensivity treatments do you rountinely use or recommend for your patients? (check all that you use) | |||||

| a. Dentin bonding agents | 244 (65%) | 245 (71%) | 132 (58%) | 0.009 | |

| b. Oxalate or bioglass containing material | 63 (17%) | 52 (15%) | 35 (15%) | 0.825 | |

| c. Fluoride containing material | 326 (86%) | 293 (85%) | 194 (86%) | ||

| d. Chemical treatment (e.g. potassium nitrate) | 164 (43%) | 127 (37%) | 113 (50%) | ||

| e. Toothpaste or rinse | 305 (81%) | 273 (79%) | 180 (80%) | ||

| f. Other | 42 (11%) | 34 (10%) | 21 (9%) | ||

| g. Nothing | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Endodontic Treatment and Restoration | |||||

| 13. One of your regular patients presents with pain in tooth #13. Upon clinical inspection the lingual cusp has fractured to just below the gingival margin and there is extensive decay beneath the large MOD composite restoration. | |||||

| You are able to diagnose a condition of irreversible pulpitis but there is no radiographic evidence of periapical pathosis. You would at this point recommend to your patient that you: | N | 372 | 336 | 220 | 0.016 |

| Initiate endodontic treatment leading to placement of a post and core followed by a full crown | 253 (68%) | 222 (66%) | 125 (57%) | ||

| Extirpate pulp, temporize, refer for endodontic treatment and place a post, core and full crown | 64 (17%) | 73 (22%) | 60 (27%) | ||

| Extract tooth and place an immediate implant fixture and later restore with a crown | 18 (5%) | 9 (3%) | 11 (5%) | ||

| Extirpate pulp, temporize, refer for extraction and placement of implant, and restore with crown | 23 (6%) | 10 (3%) | 12 (5%) | ||

| Extract tooth, refer patient for placement of an implant ficture, and restore with crown | 14 (4%) | 22 (7%) | 12 (5%) |

Full participant: respondent has participated in at least one network study recruiting patients

Partial participant: respondent is a fully trained member of the network or has attended at least one meeting or participated in other survey studies

Reference: inactive member of the network (not trained, no participation in studies or meetings) or is outside the network, e.g. Friends of PRECEDENT

Treatment recommendations were requested for two molars in a 30 year old female patient with no other teeth with dental restorations or caries. For the tooth shown in Figure 1A, 29% chose no treatment or further diagnostic testing, while 56% recommended minimally invasive and/or preventive treatment (Table 3). These numbers were consistent across provider experience but not across levels of network participation (p=0.006). Full participants were more likely to recommend preventive or minimally invasive care (60%) compared to partial participants (50%) or the reference group (55%, Table 4). For the second tooth (Figure 1B), 48% recommended minimally invasive and/or preventive treatment. Again, full participants were more likely to make this recommendation than partial participants or those in the reference group (p=0.055).

Figure 1.

A & B Caries Treatment

Deep Caries Treatment

A case presentation with radiograph described a patient with visible cavitation into the dentin in the central fossa of tooth #30 (Figure 2). Respondents were asked what they would do when they realized that the lesion was deeper than anticipated and may involve the mesial buccal pulp horn. Forty-six percent would continue and remove all of the decay, 34% would stop removing decay near the pulp horn and remove it elsewhere and 20% would temporize and treat or refer the tooth for endodontics (Table 3). Observed differences across number of years post dental degree did not show a clear trend, while responses were consistent across level of involvement with the network.

Figure 2.

Deep Caries Bitewing Radiograph

Pulp Cap Materials

Almost half of respondents use calcium hydroxide as a pulp capping material (49%, Table 3), while 33% use glass ionomer. Use of mineral trioxide aggregate is more prevalent in NW-PRECEDENT (10%) compared to other networks (2-3%, data not shown). Dentin bonding systems are used by 9% and other materials by 5%. More (52%) experienced practitioners use calcium hydroxide compared to the least experienced (40%). Fewer experienced practitioners use glass ionomer (29%) compared to more recent dental graduates (46%, p<0.001). Material preferences were consistent across level of involvement with the network (Table 4).

Recommendations Regarding Third Molar Extraction

Half of respondents refer patients for third molar extraction by the age of 20, 60% or more of the time (Table 3). Most (74%) recommend removal if the molar has a poor eruption path or insufficient space for eruption (Table 3). Recent graduates recommended removal for preventive reasons more frequently (25%) compared with more experienced practitioners (p=0.003). There was no difference based on level of network participation.

Treatments for Dentin Hypersensitivity

Respondents reported using a wide variety of treatments for dentin hypersensitivity including, dentin bonding agents (65%), fluoride containing materials (85%), toothpaste or rinse (80%) and some chemical treatment (43%) (Table 3). Oxalate and dentin bonding agents were used more frequently by more experienced practitioners. Treatment patterns were consistent across level of involvement.

Endodontic Treatment and Restoration

In a fourth case presentation, respondents provided a recommendation regarding endodontic treatment in a patient presenting with pain in tooth #13 (details in Table 3, Question13). Most recommended initiating endodontic treatment leading to a post, core and full crown (65%) (Table 3). Some (21%) recommended extirpation of the pulp, temporizing and referring for endodontic treatment; 14% chose an option that included an implant. Recommendations were consistent across years of experience. Slightly more reference respondents recommended extirpation of the pulp (27%) or options that included an implant (16%) compared with network practitioners (p=0.016,Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Progress towards improving the oral health status of Americans has been impeded at least in part due to reliance on passive methods to disseminate the latest scientific evidence into daily clinical practice.17 PBRNs provide an excellent opportunity to close the gap between research and practice, while generating important and relevant knowledge that can be applied in daily clinical dental practices.18,19,20 The active participation of dental practitioners in PBRNs could enhance the much needed translation and implementation of evidence-based research into practice.22,23,21

This survey provides an important baseline from which to measure practice changes as studies from the PBRNs are completed, published and results disseminated. Results are confined to US practices. Because the three PBRNs span the nation, the sample provides an opportunity to identify regional differences in practice patterns and changes in practice patterns over time. Dentists who joined the PBRNs are a self-selected population with specific interest in research and may be more willing to alter clinical practice to reflect outcomes suggested in research studies. The reference group will help delineate differences, if any, in research-focused practitioners compared to a more general practitioner population; however, even they may differ from the general dentist because they have expressed some interest in a research network.

A comparison of the baseline characteristics with survey results from the American Dental Association (ADA) suggests PBRN dentists have some similar demographics compared to the practitioners who participated in the ADA survey. Across the networks, 81% of dentists are male consistent with ADA survey data showing 78.6% of practicing dentists are male.24 However, PBRN dentists tend to have been practicing for fewer years than the general practitioner population with 48% of PBRN dentists practicing less than 20 years compared to 30.5% nationally.24 This may reflect an age-dependent trend in which more recent graduates have an increased belief in the value of participating in and implementing high-quality scientific evidence into daily practice .25 Interestingly, applicants for the ADA's Evidence-based Dentistry Champions Conference in 2010 averaged 20.7 years of practice experience, similar to PBRN participants.26,27 Perhaps not surprisingly, there is a highly significant shift in gender distribution associated with years in practice. A higher proportion of women (66.1%) are represented in the group practicing 15 or fewer years which is to be expected considering there has been a 47.6% increase in female dental graduates since 1999.

Although the survey was piloted for understanding and completion time, dentists may have been inconsistent in their interpretation of some of the items. For example, pulp capping may have been interpreted as either indirect or direct pulp capping for which different materials may be indicated.28, 29 The assessments of consistency in responses by the same dentists over a period of time where real change is not expected, found poor reliability of responses for treatment of dentin hypersensitivity with fluoride containing materials, toothpaste, or chemical treatment. Good to excellent reliability was found for most of the remaining items suggesting that this survey could be a useful measure for detecting change in practice in the targeted areas of caries diagnosis and treatment, third molar extraction, and endodontic treatment. Because of the number of comparisons, these conclusions must be considered exploratory, requiring further verification.

Although there has been a recent trend in recommendations against the prophylactic removal of third molars30,31 newer dental graduates were more likely to recommend removal of third molars for this reason. The reasons for this trend are not immediately evident.

Dentists with more than 15 years in practice were less likely to use a special form to record caries risk. But, full participants in network research were nearly twice as likely to record caries risk assessments data on a special form. This trend may reflect the network participants’ intellectual interest in the concept of scientific inquiry. Full and partial participants were more likely to initiate endodontic therapy to address irreversible pulpitis compared to the reference group. Full participants were more likely to recommend preventive or minimally invasive treatment for presented examples of caries in a low risk individual compared to partial participants and reference groups perhaps reflecting full participants’ knowledge of current PBRN studies of caries treatment approaches and/or their willingness to consider alternatives.

In summary, the demographic characteristics of the CONDOR research network practitioners are similar to their US colleagues, but our data suggest they show a more evidence-based approach to their practice. This could be due to the emphasis within the network of engaging the dental practitioners in each step of the research process including what to study, how to study it, how to evaluate the results, and presentation of the results to colleagues; an approach used by others.32,33,34,35 One of the objectives of the repeated administration of this survey is to identify if those most involved in the research enterprise are the most likely to be early adopters of new practices identified through research. In addition, among full participants we plan to investigate whether those enrolling subjects in a study whose results are compelling enough to change practice will be more likely to change practice than those who did not participate in that study. These investigations may offer information on characteristics associated with faster translation of research results into practice36; a goal that is important across many public health disciplines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Damon Collie, PEARL, Ellen Funkhauser, DrPH, DPBRN and Yang Wang, PhD and Xiaohui (Julie) Huang,MS, from NW-PRECEDENT for their assistance in the preparation of analyses for this manuscript.

Research supported by grants from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health cooperative agreements U01-DE-16746 and U01-DE-16747 for DPBRN, U01-DE-16750 and U01-DE-16752 for NW-PRECEDENT and U01-DE-16754 and U01-DE-16755 for PEARL, and U19-DE-22516.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ruth McBride, Axio Research, LLC, Seattle, WA.

Brian Leroux, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Anne Lindblad, The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, MD.

O. Dale Williams, Florida International University, Miami, FL.

Maryann Lehmann, Private Practice, Darien, CT..

D. Brad Rindal, HealthPartners, Minneapolis, MN.

Maria Botello-Harbaum, The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, MD.

Gregg H. Gilbert, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Jane Gillette, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland OH..

MT Bozeman, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland OH..

Catherine Demko, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland OH..

REFERENCES

- 1.Giannobile WV. Promotion of oral, dental, and craniofacial research. Journal Dental Research. 2010;89(10):1013–5. doi: 10.1177/0022034510383258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balas EA, Boren SA. Evidence-based quality measurement. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 1999;22(3):17–23. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199907000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckett M, Quiter E, Ryan G, Berrebi C, Taylor S, Cho M, Pincus H, Kahn K. Bridging the gap between basic science and clinical practice: the role of organizations in addressing clinician barriers. Implementation Science. 2011;6(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBride R. Translation of research into practice. In: Giannobile WV, et al., editors. Clinical Research on Oral Health. Wiley-Blackwell; Iowa: 2010. pp. 288–289. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodenheimer T, Young DM, MacGregor K, Holtrop JS. Practice-based research in primary care: facilitator of, or barrier to, practice improvement? The Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(Suppl 2):S28–32. doi: 10.1370/afm.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawes M, Sampson U. Knowledge management in clinical practice: a systematic review of information seeking behavior in physicians. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2003;71(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarkson J. Experience of clinical trials in general dental practice. Advances in Dental Research. 2005;18(3):39–41. doi: 10.1177/154407370501800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ploeg J, Davies B, Edwards N, Gifford W, Miller PE. Factors influencing best-practice guideline implementation: lessons learned from administrators, nursing staff, and project leaders. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2007;4(4):210–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2007.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNucci DJ, CONDOR . Dental practice-based research networks. In: Giannobile WV, et al., editors. Clinical Research on Oral Health. Wiley-Blackwell; Iowa: 2010. pp. 265–293. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeRouen TA, Cunha-Cruz J, Hilton T J, Ferracane J, Berg J, Zhou L, Rothen M. What's in a dental practice-based research network? Characteristics of Northwest PRECEDENT dentists, their patients and office visits. Journal of American Dental Association. 2009;141(7):889–99. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Benjamin PL, Wallace MC. The creation and development of the dental practice-based research network. Journal of American Dental Association. 2008;139(1):74–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curro FA, Craig R, Thompson V. Practice-based research networks and their impact on dentistry: creating a pathway for change in the profession. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 2009;30(4):184, 186–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botello-Harbaum MT, Demko CA, Curro FA, Rindal DB, Collie D, Gilbert GH, et al. “Information-Seeking Behaviors of Dental Practitioners in Three Practice-Based Research Networks”. Journal of Dental Education. 2013;77(2):152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brad Rindal D, Gordan Valeria V., Litaker Mark S., Bader James D., Fellows Jeffrey L., Qvist Vibeke, Wallace-Dawson Martha C., Anderson Mary L., Gilbert Gregg H. For The DPBRN Collaborative Group, which includes practitioner-investigators, faculty investigators, and staff investigators who contributed to this activity. Methods dentists use to diagnose primary caries lesions prior to restorative treatment: Findings from The Dental PBRN. Journal of Dentistry. 2010 Dec;38(12):1027–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordan VV, Bader JD, Garvan CW, Richman JS, Qvist V, Fellows JL, Rindal DB, Gilbert GH. Restorative treatment thresholds for occlusal primary caries among dentists in the dental practice-based research network. Journal of American Dental Association. 2010;141(2):171–84. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7156):465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabak LA. Dental, oral, and craniofacial research: the view from the NIDCR. Journal of Dental Research. 2004;83(3):196–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ship JA, Curro FA, Caufield PW, Dasanayake AP, Lindblad A, Thompson VP, Vena D. Practicing dentistry using findings from clinical research: You are closer than you think. Journal of American Dental Association. 2006;137(11):1488–1491. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green LA, White LL, Barry HC, Nease DE, Jr., Hudson BL. Infrastructure requirements for practice-based research networks. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(Suppl 1):S5–11. doi: 10.1370/afm.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makhija SK, et al. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. BioMed Central Oral Health. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beasley JW, Karsh BT, Hagenauer ME, Marchand L, Sainfort F. Quality of Work Life of Independent vs Employed Family Physicians in Wisconsin: A WReN Study. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(6):500–506. doi: 10.1370/afm.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watt RP, McGlone P, Evans D, Boulton S, Jacobs J, Graham S, Appleton T, Perry S, Sheiham A. The facilitating factors and barriers influencing change in dental practice in a sample of English general dental practitioners. British Dental Journal. 2004;197(8):485–489. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The American Dental Association Workforce Distribution of Dentists in the United States by Region and State. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 25.The American Dental Association Dental Practice, Survey of Dental Practice Characteristics of Dentists in Private Practice and their Patients. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bader J. The Forth Phase. Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice. 2004;4:12–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The American Dental Association 2010 Evidence-Based Dentistry Champion Conference: Pre-conference, On-site Workshop, On-site Conference, and Follow-Up Surveys. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson V, Craig R, Curro F, Green W, Ship J. Treatment of deep carious lesions by complete or partial removal. A critical review. Journal of American Dental Association. 2008;139(6):705–712. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyashita H, Worthington HV, Qualtrough A, Plasschaert A. Pulp management for caries in adults: maintaining pulp vitality. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004484.pub2. Art. No.: CD004484. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004484.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The American Public Health Association [March 22, 2011];Opposition to Prophylactic Removal of Third Molars (Wisdom Teeth) http://www.apha.org/advocacy/policy/policysearch/default.htm?id=1371.

- 31.Mettes DTG, Nienhuijs MMEL, van der Sanden WJM, Verdonschot EH, Plasschaert A. Interventions for treating asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth in adolescents and adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003879.pub2. Art. No.: CD003879. DOI: 10. 1002/14651858.CD003879.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting HH, Shojania KG, Montori VM, Bradley EH. Quality improvement: science and action. Circulation. 2009;119(14):1962–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. British Dental Journal. 2001;190(12):636–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Wijk MA, van der Lei J, Mosseveld M, Bohnen AM, van Bemmel JH. Compliance of general practitioners with a guideline-based decision support system for ordering blood tests. Clinical Chemistry. 2002;48(1):55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342(8883):1317–22. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Momoi Y, Hayashi M, Fujitani M, Fukushima M, Imazato S, Kubo S, Nikaido T, Shimizu A, Unemori M, Yamaki C. Clinical guidelines for treating caries in adults following a minimal intervention policy-Evidence and consensus based report. Journal of Dentistry. 2012 Feb;40(2):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.