Abstract

The allele 1691A F5, conferring Factor V Leiden, is a common risk factor in venous thromboembolism. The frequency distribution for this allele in Western Europe has been well documented; but here data from Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe has been included. In order to assess the significance of the collated data, a chi-squared test was applied, and Tukey tests and z-tests with Bonferroni correction were compared. Results: A distribution with a North-Southeast band of high frequency of the 1691A F5 allele was discovered with a pocket including some Southern Slavic populations with low frequency. European countries/regions can be arbitrarily delimited into low (group 1, <2.8 %, mean 1.9 % 1691A F5 allele) or high (group 2, ≥2.8 %, mean 4.0 %) frequency groups, with many significant differences between groups, but only one intra-group difference (the Tukey test is suggested to be superior to the z-tests). Conclusion: In Europe a North-Southeast band of 1691A F5 high frequency has been found, clarified by inclusion of data from Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, which surrounds a pocket of low frequency in the Balkans which could possibly be explained by Slavic migration. There seem to be no indications of variation in environmental selection due to geographical location.

Keywords: Allele frequency distribution, Factor V, FV Leiden, Tukey tests, Venous thromboembolism

Introduction

The gene F5 encodes for blood coagulation Factor V, and the 1691G>A F5 transition in exon 10 causes a substitution (R506Q) known as Factor V Leiden. This genetic variant is the most common hereditable risk factor for thromboembolic disease (Kujovich 2011). Clinical observations with the 1691A F5 allele include an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (Koster et al. 1993; Ridker et al. 1998; Rosendorff and Dorfman 2007), and 1691A F5 is also associated with an increased risk for pregnancy loss and possibly other obstetric complications (Ridker et al. 1998; Foka et al. 2000), these effects being semi-dominant.

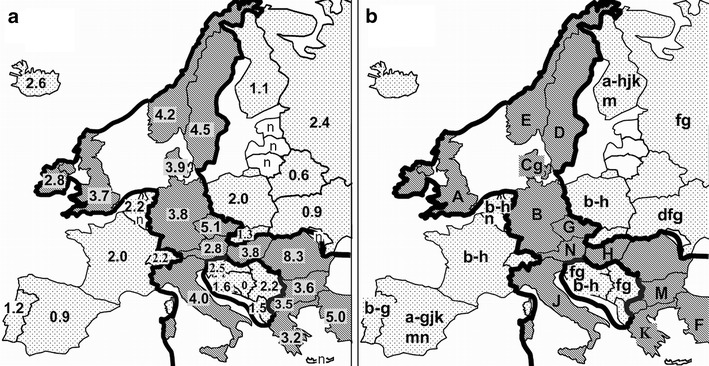

The 1691A F5 allele is thought to have originated with a single mutation event which took place 21,000–34,000 years ago (Zivelin et al. 1997). The 1691A F5 allele appears to be generally confined to Indo-Europeans: the 1691A allele is very rare or non-existent in Asia (0.6 %) and some regions of Africa (0.0 %) (Hira et al. 2002; Nasiruddin et al. 2005; They-They et al. 2010); but note that Settin et al. (2008) reported a frequency of 10.2 % in Egypt. In various parts of Europe the frequency of this variant has been described as uneven (Rees et al. 1995; Herrmann et al. 1997; Paseka et al. 2000; Adler et al. 2010), with high frequencies observed in the Czech Republic (5.1 %, n = 2819) (Prochazka et al. 2003) and Turkey (5.0 %, n = 2003) (see Fig.1 for references).

Fig. 1.

a. Average allele frequencies for 1691A F5 across Europe. b. Significant differences between countries. a. 1691A F5 frequencies:  >3 %,

>3 %,  <3 % (n.d. = no data). Slavic data (Adler et al. 2012): Poland

n = 1588, Czech Republic

n = 2819, Slovakia

n = 152, Slovenia

n = 526, Croatia

n = 749, Serbia/Montenegro

n = 499; Macedonia

n = 130, Bulgaria

n = 506, Russia

n = 539, Ukraine

n = 172, Belarus

n = 80; Bosnia/Herzegovina

n = 67 (Valjevac et al. 2013). Other data: Group 1: Albania (n = 70; Arsov et al. 2006), Austria (n = 572; Gisslinger et al. 1995, Lalouschek et al. 2005), Finland (n = 1285; Hiltunen et al. 2007), France (n = 1242; Leroyer et al. 1997; Baba-Ahmed et al. 2007; Pasquier et al. 2009), Iceland (n = 96; Rees et al. 1995), Netherlands (n = 2631; Rosendaal et al. 1995; Heijmans et al. 1998; van Dunne et al. 2006), Portugal (n = 303; Ferrer-Antunes et al. 1995; Serrano et al. 2011), Spain (n = 889; Garcia-Gala et al. 1997; Aznar et al. 2000; Frances et al. 2006), Switzerland (n = 100; Redondo et al. 1999). Group 2: Denmark (n = 20242; Larsen et al. 1998; Juul et al. 2002; Benefield et al. 2005), Germany (n = 2199; Aschka et al. 1996; Schambeck et al. 1997; Nabavi et al. 1998; Ehrenforth et al. 1999; Lichy et al. 2006; Toth et al. 2008), Greece (n = 932; Foka et al. 2000; Rees et al. 1995; Lambropoulos et al. 1997; Antoniadi et al. 1999; Ioannou et al. 2000; Aronis et al. 2002; Komitopoulou et al. 2006), Hungary (n = 1196; Tordai et al. 1997; Stankovics et al. 1998; Szolnoki et al. 2001; Shemirani et al. 2011), Italy (n = 226; De Stefano et al. 1999; Sottilotta et al. 2009), Norway (n = 807; Ulvik et al. 1998; Berge et al. 2007), Romania (n = 42; Fischer et al. 2006), Sweden (n = 1343; Svensson et al. 1997; Kjellberg et al. 2010), Turkey (n = 2003; Ozbek and Tangun 1996; Akar et al. 1997; Gurgey and Mesci 1997, Atasay et al. 2003; Agaoglu et al. 2005; Eroglu et al. 2006; Ulukus et al. 2006), U.K. (n = 491; Rees et al. 1995; Catto et al. 1999). b. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between 1691A F5 allele frequency values in European countries, as analyzed by Tukey tests. Capital letters indicate countries with high frequency values significantly different from at least one country; lower case letters indicate which countries had significantly different, and lower, allele frequencies than those with the corresponding capital letter

<3 % (n.d. = no data). Slavic data (Adler et al. 2012): Poland

n = 1588, Czech Republic

n = 2819, Slovakia

n = 152, Slovenia

n = 526, Croatia

n = 749, Serbia/Montenegro

n = 499; Macedonia

n = 130, Bulgaria

n = 506, Russia

n = 539, Ukraine

n = 172, Belarus

n = 80; Bosnia/Herzegovina

n = 67 (Valjevac et al. 2013). Other data: Group 1: Albania (n = 70; Arsov et al. 2006), Austria (n = 572; Gisslinger et al. 1995, Lalouschek et al. 2005), Finland (n = 1285; Hiltunen et al. 2007), France (n = 1242; Leroyer et al. 1997; Baba-Ahmed et al. 2007; Pasquier et al. 2009), Iceland (n = 96; Rees et al. 1995), Netherlands (n = 2631; Rosendaal et al. 1995; Heijmans et al. 1998; van Dunne et al. 2006), Portugal (n = 303; Ferrer-Antunes et al. 1995; Serrano et al. 2011), Spain (n = 889; Garcia-Gala et al. 1997; Aznar et al. 2000; Frances et al. 2006), Switzerland (n = 100; Redondo et al. 1999). Group 2: Denmark (n = 20242; Larsen et al. 1998; Juul et al. 2002; Benefield et al. 2005), Germany (n = 2199; Aschka et al. 1996; Schambeck et al. 1997; Nabavi et al. 1998; Ehrenforth et al. 1999; Lichy et al. 2006; Toth et al. 2008), Greece (n = 932; Foka et al. 2000; Rees et al. 1995; Lambropoulos et al. 1997; Antoniadi et al. 1999; Ioannou et al. 2000; Aronis et al. 2002; Komitopoulou et al. 2006), Hungary (n = 1196; Tordai et al. 1997; Stankovics et al. 1998; Szolnoki et al. 2001; Shemirani et al. 2011), Italy (n = 226; De Stefano et al. 1999; Sottilotta et al. 2009), Norway (n = 807; Ulvik et al. 1998; Berge et al. 2007), Romania (n = 42; Fischer et al. 2006), Sweden (n = 1343; Svensson et al. 1997; Kjellberg et al. 2010), Turkey (n = 2003; Ozbek and Tangun 1996; Akar et al. 1997; Gurgey and Mesci 1997, Atasay et al. 2003; Agaoglu et al. 2005; Eroglu et al. 2006; Ulukus et al. 2006), U.K. (n = 491; Rees et al. 1995; Catto et al. 1999). b. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between 1691A F5 allele frequency values in European countries, as analyzed by Tukey tests. Capital letters indicate countries with high frequency values significantly different from at least one country; lower case letters indicate which countries had significantly different, and lower, allele frequencies than those with the corresponding capital letter

We provide a summary study of the frequency distribution of 1691A F5 across Europe by addition of values from 12 countries/regions which are predominantly populated by Slavic populations (note that Serbia and Montenegro separated in 2006 - data in this article precede this date).

Materials and methods

The databases Medline (U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, USA) and several websites providing local language articles (e.g., www.google.ba for Bosnia/Herzegovina, www.google.hr for Croatia; Google Inc., Mountain View, California, USA) were searched until March 2012. Keywords and/or mesh terms used were (together with country/region names): “1691A F5”, “Leiden”, “FV’, “F5”, “FVL”, “Factor 5”, “fv”. Data for Bosnia/Herzegovina were obtained from our previous study (Valjevac et al. 2013). Data were included from: groups of blood donors, those defined as “healthy” adults in case–control studies, and population groups. Summary data in Europe for NM_000130.4:c.1691G>A F5 is presented as a map.

In order to test the significance of the resulting distribution, a chi-squared test for independence (Ulukus et al. 2006) and post-hoc pair-wise proportion comparison tests were carried out between all countries by two methods: (1) as in Zar (1999): tests analogous to, and refered to here as, “Tukey tests” (critical values from R package DKT; Lau 2011); (2) z-tests with Bonferroni correction (Microsoft Excel 2007, Redmond, WA, USA; http://www.csun.edu/~vchsc006/469/z.html). The critical significance level was set at p = 0.05.

Results

A map showing average frequencies for 1691A F5 throughout Europe is given in Fig. 1a.

Comparison of the 1691A F5 allele frequency values in all populations, assessed by the chi-squared test, gave a significant value (p < 0.001) showing the presence of differences between countries/regions.

The thick line in Fig. 1 arbitrarily delimits a group of countries with low frequency (group 1) from those with high frequency (group 2), with an arbitrary cut-off at 2.8 %. Although this was an arbitrary cut-off, with post-hoc Tukey and z-tests the two groups of countries/regions were found to have only one intra-group significant difference (between Czech Republic, 5.1 %, n = 2819; and Denmark, 3.9 %, n = 20242), but many significant differences between the groups (Fig.1b).

Group 1 consisted of countries/region with 1691A F5 allele frequency <2.8 %; the average frequency in the group was 1.9 %. Countries in group 1 included: Russia, Finland, Ukraine, Poland, Slovenia, Serbia/Montenegro, Croatia, The Netherlands, France, Spain, Portugal (these countries have reasonable sample sizes, and each has at least one significant difference with another country’s value). If those countries with no significant differences at all (with smaller sample sizes) were included, then this group consisted of most (ten) Slavic populations together with another eight non-Slavic countries (Fig.1).

Group 2 consisted of countries with 1691A F5 allele frequency ≥2.8 %; the average frequency in the group was 4.0 %: Countries with at least one pair-wise significant difference by Tukey tests included: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany, U.K., The Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. Including those countries with no significant differences at all (with small sample sizes), this group consisted of 13 countries including the predominantly Slavic countries Czech Republic and Bulgaria (Fig. 1).

Tukey tests and z-tests gave similar numbers of pair-wise differences between countries (66 and 59, respectively; Tukey test results are shown in Fig.1b.; z-test results not shown). However, the Tukey tests defined statistically significant differences involving Slovenia (2.5 %, n = 526), Russia (2.4 %, n = 539) and Serbia and Montenegro (2.2 %, n = 499), which were not identified using z-tests, whereas z-tests defined differences involving Romania (8.3 %, n = 42 - note the very small sample size). Additionally the other Tukey test differences were more evenly distributed whereas with z-tests most differences were concentrated on Spain (2.0 %, n = 889), and Finland (1.1 %, n = 1285).

Discussion

In Europe the average 1691A F5 allele frequency was found to be 3.5 % (n = 44,627, references in Fig.1).

In order to highlight the distribution of high frequency populations, European countries/regions were arbitrarily divided into two groups: with low (group 1) or high frequency (group 2), with an arbitrary boundary at 2.8 % (delineated by thick lines in Fig. 1). The group of high frequency countries (i.e., group 2) was found to have a North-Southeast band distribution. A pocket of low frequency with some Southern Slavic countries (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia and Montenegro) and Albania (although note low sample size) was found to be enclosed by this band of high frequency. We can therefore surmise that the band of high frequency was created by founder effect seeding, and the pocket of low frequency might have been created with the purported movement of Eastern Slavic populations with low frequency to this region in the fifth to seventh centuries. However, conclusions referring to the migration of Slavic peoples have to take into account the fact that the Czech Republic and Bulgaria have high frequencies of this allele. Especially note that the Czech Republic has the highest frequency value in Europe (5.1 %; with a reasonable sample size of 2819) but note that this value is not significantly different to values in the neighboring countries Germany and Austria. Additionally, therefore, it could be hypothesized that these result from high influx of peoples carrying the variant from neighboring populations.

It is not known to what extent positive or negative selection acts on this allele - it is thought that the negative impact of 1691A F5 before reproductive age exists but reports in children are scanty (El-Karaksy and El-Raziky 2011). From the North-Southeast band of high frequency of the 1691A F5 allele there seem to be no indications of possible environmental effects which could vary according to location (and act as selection) on this allele.

Although such a map in Fig. 1 is informative, the statistical significance of the distribution found depends directly on the sample sizes of the data (see legend to Fig.1). Additionally, there are several ways to do post-hoc pair-wise comparison tests between countries, which take into account sample sizes. By using Tukey tests or z-tests it was found that there was only one intra-group significant difference (within group 2 between Czech Republic and Denmark; Fig.1b), but many significant differences between groups. (Significance maps at the p = 0.01 level, for either test, were very similar - not shown.)

This means that inferences from individual country values should be made with caution, and the high frequency group of countries could be treated more or less as one block (and likewise for the low frequency group). The map in Fig. 1 represents the present state of knowledge concerning the distribution of the 1691G>A F5 allele, and theoretically increasing the sample sizes would increase the number of pair-wise statistical differences shown in Fig.1b. It should be noted, however, that several sample sizes are already reasonably large e.g., The Netherlands (2.2 %, n = 2631), Germany (3.8 %, n = 2199) but show no intra-group significant differences by either of the methods used.

Despite the overall similarities in the conclusions drawn from the Tukey and z-tests, it should be noted that these analyses suggest (and confirm) the appropriateness of Tukey tests, rather than z-tests with Bonferroni correction, for this type of study. The reason for this is that any inference from differences involving Romania with only 42 subjects is rather dubious (as is the rather high allele sample frequency of 8.3 %, which might not be a good representation of the frequency in the population). The z-tests, however, gave six differences, between Romania and: Finland, Poland, Ukraine, Croatia, Spain, and Portugal (data not shown), whereas the Tukey tests gave no significant differences involving Romania (Fig.1b).

The clinical effects of the 1691A F5 variant are fairly well established, with a three to eight-fold increased thrombotic risk for heterozygotes, and up to 80-fold increased risk for homozygotes, found in a pooled analysis of eight case–control studies with over 2300 cases from Western European countries (Emmerich et al. 2001). In a Croatian case–control study (with 160 cases) a high frequency of thromboembolism was also found to be associated with the 1691A F5 allele: 21 % of patients with venous thromboembolism carried the 1691A F5 allele, but only 4 % of healthy controls (Coen et al. 2001). Further studies could be done to confirm whether or not the presence of the 1691A F5 allele does indeed provide a similar risk for venous thromboembolism across Europe.

Conclusions

In summary, a North-Southeast band distribution of 1691A F5 high frequency in Europe was found by the addition of data collated and presented from Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. A pocket of low frequency in some Southern Slavic countries was found to be enclosed by this band of high frequency. The reasons for this distribution are not known, but perhaps reflect founder effects following migration after the last ice age, followed by the migration of Slavic peoples from the fifth century. There seem to be no indications of variation in environmental selection due to geographical location.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. We would like to thank the anonymous expert at scientific English language who corrected this article.

Footnotes

Jeremy S. C. Clark and Grażyna Adler have an equal contribution to this work.

Contributor Information

Jeremy S. C. Clark, Phone: +48-91-4800958, FAX: +48-91-4800958, Email: jeremyclarkmel@gmail.com

Grażyna Adler, Phone: +48-91-4800958, FAX: +48-91-4800958, Email: gra2@op.pl.

References

- Adler G, Clark JS, Loniewska B, Czerska E, Salkic NN, Ciechanowicz A. Prevalence of 1691G>A FV mutation in Poland compared with that in other Central, Eastern and South-Eastern European countries. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2012;12(2):82–87. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2012.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler G, Parczewski M, Czerska E, Loniewska B, Kaczmarczyk M, Gumprecht J, et al. An age-related decrease in factor V Leiden frequency among Polish subjects. J Appl Genet. 2010;51:337–341. doi: 10.1007/BF03208864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agaoglu N, Turkyilmaz S, Ovali E, Uçar F, Ağaoğlu C. Prevalence of prothrombotic abnormalities in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. World J Surg. 2005;29:1135–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7692-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar N, Akar E, Dalgin G, Sözüöz A, Omürlü K, Cin S. Frequency of Factor V (1691 G -> A) mutation in Turkish population. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:1527–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniadi T, Hatzis T, Kroupis C, Economou-Petersen E, Petersen MB. Prevalence of Factor V Leiden, prothrombin G(20210A, and MTHFR C677T variants in a Greek population of blood donors. Am J Hematol. 1999;61:265–267. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199908)61:4<265::AID-AJH8>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronis S, Bouza H, Pergantou H, Kapsimalis Z, Platokouki H, Xanthou M. Prothrombotic factors in newborns with cerebral thrombosis and intraventricular hemorrhage. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2002;91:87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsov T, Miladinova D, Spiroski M. Factor V Leiden is associated with higher risk of deep venous thrombosis of large blood vessels. Croat Med J. 2006;47:433–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschka I, Aumann V, Bergmann F, Budde U, Eberl W, Eckhof-Donovan S, et al. Prevalence of factor V Leiden in children with thrombo-embolism. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:1009–1014. doi: 10.1007/BF02532520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasay B, Arsan S, Gunlemez A, Kemahli S, Akar N. Factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene 20210A variant in neonatal thromboembolism and in healthy neonates and adults: a study in a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20:627–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznar J, Vayá A, Estellés A, Mira Y, Seguí R, Villa P, et al. Risk of venous thrombosis in carriers of the prothrombin G20210A variant and Factor V Leiden and interaction with oral contraceptives. Haematologica. 2000;85:1271–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba-Ahmed M, Le Gal G, Couturaud F, Lacut K, Oger E, Leroyer C. High frequency of factor V Leiden in surgical patients with symptomatic venous thromboembolism despite prophylaxis. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benefield TL, Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Influence of the Factor V Leiden variant on infectious disease susceptibility and outcome: a population-based study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1851–1857. doi: 10.1086/497167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge E, Haug KBF, Sandset EC, Haugbro KK, Turkovic M, Sandset PM. The factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene 20210GA, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677CT and platelet glycoprotein IIIa 1565TC mutations in patients with acute ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2007;38:1069–1071. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258076.04860.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catto AJ, Kohler HP, Coore J, Mansfield MW, Stickland MH, Grant PJ. Association of a common polymorphism in the factor XIII gene with venous thrombosis. Blood. 1999;93:906–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen D, Zadro R, Honović L, Banfić L, Stavljenić Rukavina A. Prevalence and association of the factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A in healthy subjects and patients with venous thromboembolism. Croat Med J. 2001;42:488–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano V, Zappacosta B, Persichilli S, Rossi E, Casorelli I, Paciaroni K, et al. Prevalence of mild hyperhomocysteinaemia and association with thrombophilic genotypes (factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A) in Italian patients with venous thromboembolic disease. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:564–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenforth S, Klinke S, von Depka Prondzinski M, Kreuz W, Ganser A, Scharrer I. Activated protein C resistance and venous thrombophilia: molecular genetic prevalence study in the German population. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1999;124:783–787. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Karaksy H, El-Raziky Splanchnic vein thrombosis in the mediterranean area in children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2011;3:e2011027. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2011.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich J, Rosendaal FR, Cattaneo M, Margaglione M, De Stefano V, Cumming T, Arruda V, Hillarp A, Reny JL. Combined effect of factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A on the risk of venous thromboembolism–pooled analysis of 8 case–control studies including 2310 cases and 3204 controls. Study Group for Pooled-Analysis in Venous Thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu Z, Biray Avci C, Kilic M, Kosova B, Özen E, Gündüz C, Topçuoğlu N. The prevalence of Factor V Leiden gene variant analysis of donor and recipient at the organ transplantation. Cent Ege Univ Ege Tip Dergisi. 2006;45:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Antunes C, Palmeiro A, Green F, Rosa H, Feliciano B, Silva E. Polymorphisms of fibrinogen, Factor VIII and Factor V genes Comparison of allele frequencies in different ethnic groups. Thromb Haemostasis. 1995;73:18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Procopciuc L, Jebeleanu G. Analysis of Factor V Leiden in women with fetal loss using single strand conformation polymorphism. TMJ. 2006;56:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Foka ZJ, Lambropoulos AF, Saravelos H, Karas GB, Karavida A, Agorastos T, et al. Factor V leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations, but not methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T, are associated with recurrent miscarriages. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:458–462. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frances F, Portoles O, Gabriel F, Corella D, Sorlí JV, Sabater A, Alfonso JL, Guillén M. Factor V Leiden (G1691A) and prothrombin-G20210A alleles among patients with deep venous thrombosis in the general population from Spain. Rev Med Chil. 2006;134:13–20. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872006000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gala JM, Alvarez V, Pinto CR, Soto I, Urgellés MF, Menéndez MJ, Carracedo C, López-Larrea C, Coto E. Factor V Leiden (R506Q) and risk of venous thromboembolism: a case–control study based on the Spanish population. Clin Genet. 1997;52:206–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisslinger H, Rintelen C, Mannhalter C, Pabinger I, Geissler K, Knobl P, Eichinger S, Lechner K. Factor V Leiden variant is not a major cause of thrombotic tendency in essential thrombocythemia (ET) polycythemia vera (PV) (Abstract) Blood. 1995;86(Suppl):795a. [Google Scholar]

- Gurgey A, Mesci L. The prevalence of factor V Leiden (1691 G->A) mutation in Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 1997;39:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans BT, Westendorp RG, Knook DL, Kluft C, Slagboom PE. The risk of mortality and the factor V Leiden mutation in a population-based cohort. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80:607–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann FH, Koesling M, Schoeder W, Altman R, Jiménez Bonilla R, Lopaciuk S, Perez-Requejo JL, Singh JR. Prevalence of Factor V Leiden variant in various populations. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14:403–411. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1997)14:4<403::AID-GEPI5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltunen L, Rautanen A, Rasi V, Kaaja R, Kere J, Krusius T, Vahtera E, Paunio M. An unfavorable combination of Factor V Leiden with age, weight, and blood group causes high risk of pregnancy-associated venous thrombosis: a population-based nested case–control study. Thromb Res. 2007;119:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hira B, Pegoraro RJ, Rom L, Govender T, Moodley J. Polymorphisms in various coagulation genes in black South African women with placental abruption. BJOG. 2002;109:574–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou HV, Mitsis M, Eleftheriou A, Matsagas M, Nousias V, Rigopoulos C, Vartholomatos G, Kappas AM. The prevalence of factor V Leiden as a risk factor for venous thromboembolism in the population of North-Western Greece. Int Angiol. 2000;19:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul K, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Kofoed S, Jensen G, Nordestgaard BG. Factor V Leiden: Copenhagen City Heart Study; 2 meta-analyses. Blood. 2002;100:3–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellberg U, van Rooijen M, Bremme K, Hellgren M. Factor V Leiden variant and pregnancy-related complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:469e1–469e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komitopoulou A, Platokouki H, Kapsimali Z, Pergantou H, Adamtziki E, Aronis S. Mutations and polymorphisms in genes affecting hemostasis proteins and homocysteine metabolism in children with arterial ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22:13–20. doi: 10.1159/000092332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster T, Rosendaal FR, de Ronde H, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Bertina RM. Venous thrombosis due to poor anticoagulant response to activated protein C: Leiden Thrombophilia Study. Lancet. 1993;342:1503–1506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)80081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia. Genet Med. 2011;13:1–16. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181faa0f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalouschek W, Schillinger M, Hsieh K, Endler G, Tentschert S, Lang W, Cheng S, Mannhalter C. Matched case–control study on factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation in patients with ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack up to the age of 60 years. Stroke. 2005;36:1405–1409. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170635.45745.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambropoulos AF, Foka Z, Makris M, Daly M, Kotsis A, Makris PE. Factor V Leiden in Greek thrombophilic patients: relationship with activated protein C resistance test and levels of thrombin-antithrombin complex and prothrombin fragment 1 + 2. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:485–489. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199711000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TB, Lassen JF, Brandslund I, Byriel L, Petersen GB, Nørgaard-Pedersen B. The Arg506Gln mutation (FV Leiden) among a cohort of 4188 unselected Danish newborns. Thromb Res. 1998;89:211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(98)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau MK (2011) Dunnett-Tukey-Kramer Pairwise Multiple Comparison Test Adjusted for Unequal Variances and Unequal Sample Sizes. DKT version 31 Repository: CRAN

- Leroyer C, Mercier B, Escoffre M, Férec C, Mottier D. Factor V Leiden prevalence in venous thromboembolism patients. Chest. 1997;111:1603–1606. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichy C, Dong-Si T, Reuner K, Genius J, Rickmann H, Hampe T, Dolan T, Stoll F, Grau A. Risk of cerebral venous thrombosis and novel gene polymorphisms of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems. J Neurol. 2006;253:316–320. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0988-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi DG, Junker R, Wolff E, Lüdemann P, Doherty C, Evers S, et al. Prevalence of Factor V Leiden variant in young adults with cerebral ischaemia: case–control study on 225 patients. Neurol. 1998;245:653–658. doi: 10.1007/s004150050262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasiruddin, Zahur-ur-Rehman, Anwar M, Ahmed S, Ayyub M, Ali W. Frequency of Factor V leiden variant. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbek U, Tangun Y. Frequency of factor V Leiden in Turkey. Int J Hematol. 1996;64:291–292. doi: 10.1016/0925-5710(96)00499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paseka J, Unzeitig V, Cibula D, Buliková A, Matýsková M, Chroust K. The Factor V Leiden variant in users of hormonal contraceptives. Ceska Gynekol. 2000;65:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier E, Bohec C, Mottier D, Jaffuel S, Mercier B, Férec C, Collet M, De Saint Martin L. Inherited thrombophilias and unexplained pregnancy loss: an incident case–control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazka M, Happach C, Marsal K, Dahlbäck B, Lindqvist PG. Factor V Leiden in pregnancies complicated by placental abruption. BJOG. 2003;110:462–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo M, Watzke HH, Stucki B, Sulzer I, Biasiutti FD, Binder BR, Furlan M, Lämmle B, Wuillemin WA. Coagulation factors II, V, VII, and X, prothrombin gene 20210G->A transition, and Factor V Leiden in coronary artery disease: high Factor V clotting activity is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;9:1020–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.4.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Cox M, Clegg JB. World distribution of Factor V Leiden. Lancet. 1995;36:1133–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Buring JE, Ariyo AA, Price DT, Manson JE, Hill JA. Factor V Leiden mutation as a risk factor for recurrent pregnancy loss. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:1000–1003. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_Part_1-199806150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendaal FR, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Reitsma PH. High risk of thrombosis in patients homozygous for Factor V Leiden (activated protein C resistance) Blood. 1995;6:1504–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendorff A, Dorfman DM. Activated protein C resistance and Factor V Leiden: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:866–871. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-866-APCRAF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schambeck CM, Schwender S, Haubitz I, Geisen UE, Grossmann RE, Keller F. Selective screening for the Factor V Leiden mutation: is it advisable prior to the prescription of oral contraceptives? Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:1480–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano F, Lima ML, Lopes C, Almeida JP, Branco J. Factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A in Portuguese women with recurrent miscarriage: is it worthwhile to investigate? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1127–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1834-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settin A, Dowaidar M, El-Baz R, Abd-Al-Samad A, El-Sayed I, Nasr M. Frequency of factor V Leiden mutation in Egyptian cases with myocardial infarction. Hematology. 2008;13:170–174. doi: 10.1179/102453308X316158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemirani A-H, Szomjak E, Balogh E, András C, Kovács D, Acs J, Csiki Z. Polymorphism of clotting factors in Hungarian patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon Blood. Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2011;22:56–59. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834234fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottilotta G, Mammi C, Furlo G, Oriana V, Latella C, Trapani Lombardo V. High incidence of factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A in healthy southern Italians. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;15:356–359. doi: 10.1177/1076029607310218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovics J, Melegh B, Nagy A, Kis A, Molnár J, Losonczy H, Schuler A, Kosztolányi G. Incidence of factor V G1681A (Leiden) mutation in samplings from the Hungarian population. Orv Hetil. 1998;139:1161–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson PJ, Zoller B, Mattiasson I, Dahlbäck B. The factor VR506Q mutation causing APC resistance is highly prevalent amongst unselected outpatients with clinically suspected deep venous thrombosis. J Intern Med. 1997;241:379–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.124140000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szolnoki Z, Somogyvari F, Kondacs A, Szabó M, Fodor L. Evaluation of the roles of the Leiden V mutation and ACE I/D polymorphism in subtypes of ischaemic stroke. J Neurol. 2001;248:756–761. doi: 10.1007/s004150170090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- They-They TP, Hamzi K, Moutawafik MT, Bellayou H, El Messal M, Nadifi S. Prevalence of angiotensin-converting enzyme, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, Factor V Leiden, prothrombin and apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms in Morocco. Ann Hum Biol. 2010;37:767–777. doi: 10.3109/03014461003738850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordai A, Klein I, Rajczy K, Pénzes M, Sarkadi B, Váradi A. Prevalence of factor V Leiden (Arg506Gln) in Hungary. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:466–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth B, Vocke F, Rogenhofer N, Friese K, Thaler CJ, Lohse P. Paternal thrombophilic gene mutations are not associated with recurrent miscarriage. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulukus M, Eroglu Z, Yeniel AO, Toprak E, Kosova B, Turan O, Ulukus M. Frequency of Factor V Leiden (Gc1691G>A), prothrombin (G20210A) and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (C677T) genes variants in woman with adverse pregnancy outcome. J Turkish-German Gynecol Assoc. 2006;7:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ulvik A, Ren J, Refsum H, Ueland PM. Simultaneous determination of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and Factor V Gc1691G>A FV genotypes by mutagenically separated PCR and multiple-injection capillary electrophoresis. Clin Chem. 1998;44:264–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjevac A, Mehic B, Kiseljakovic E, Ibrulj S, Garstka A, Adler G. Prevalence of 1691G>A FV mutation in females from Bosnia and Herzegovina - a preliminary report. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2013;13(1):31–33. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2013.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dunne FM, de Craen AJM, Heijmans BT, Helmerhorst FM, Westendorp RG. Gender-specific association of the Factor V Leiden variant with fertility and fecundity in a historic cohort The Leiden 85-Plus Study. Human Reprod. 2006;21:967–971. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar J (1999) Biostatistical Analysis, Fourth Edition p 564 and App64, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

- Zivelin A, Griffin JH, Xu X, Pabinger I, Samama M, Conard J, Brenner B, Eldor A, Seligsohn U. A single genetic origin for a common Caucasian risk factor for venous thrombosis. Blood. 1997;89:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]