Abstract

The significance of Th17 cells and interleukin (IL)-17A signaling in host defense and disease development has been demonstrated in various infection and autoimmune models. In addition, the generation of Th17 cells is highly influenced by microbes. However, the specific bacterial components capable of shaping Th17 responses have not been well defined. The goals of this study are to understand how a bacterial toxin, cholera toxin (CT), modulates Th17-dominated response in isolated human CD4+ T cells, and what are the mechanisms associated with this modulation. The CD4+ cells isolated from human peripheral blood are treated with CT. The levels of cytokine production and specific T helper cell responses are determined by ELISA, Luminex assay, and flow cytometry. Along with the decreased production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2), we found that CT could directly enhance the IL-17A production through a cAMP-dependent pathway. This enhancement is specific for IL-17A but not for IL-17F, IL-22 and CCL20. Interestingly, CT could increase IL-17A production only from Th17-committed cells, such as CCR6+ CD4+ T cells and in-vitro-differentiated Th17 cells. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that this direct effect occurs at a transcriptional level since CT stimulates the reporter activity in Jurkat and primary CD4+ T cells transfected with the IL-17A promoter-reporter construct. This is the first report to show that CT has the capacity to directly shape Th17 responses in the absence of antigen-presenting cells. Our findings highlight the potentials of bacterial toxins in the regulation of human Th17 responses.

Introduction

Th17 cells are pro-inflammatory cells that produce IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-26, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF- α), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 (CCL20) (1–3) and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (4). These effector cytokines are critical in host defense against different pathogens, such as Candida ablicans (5). Interestingly, the plasticity of T cells allows them to express different combination of lineage-specific or lineage-non-specific cytokines when responding to different pathogens. Therefore, an increasing number of studies have showed that bacterial products, from either commensal or pathogenic bacteria (6), such as lipopeptides, Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) ligands, could regulate Th17 responses. TLR2 signaling indirectly promotes Th17 differentiation via the induction of IL-1β, IL-23, TGF-β from activated Langerhans cells (7), whereas TLR2 signaling in CD4+ T cells also promotes Th17 responses (8).

One other candidate of these bacteria products that may directly interact with Th17 cells is bacterial toxin. The release of bacterial toxin is one of the strategies for bacteria to hijack host cell process and some of bacterial toxins can modulate the immune responses (9), such as cholera toxin (CT) from Vibrio cholera. CT is an ADP-ribosylating enterotoxin, consisting of catalytic A and B subunits, in which CT-B subunit can bind to GM1 ganglioside receptor in all nucleated cells. The released CT-A subunit interacts with host’s Gα subunit and results in the stimulation of host adenylate cyclase activity that elevates the intracellular cAMP levels in various cells. Through this mechanism, CT causes severe diarrhea via acting on intestinal epithelial cells (10).

It has become clear that CT modulates immune functions via interacting with polyclonal B and T cells, as well as antigen-presenting cells (11). CT administration with antigens in mice has significantly induced intestinal sIgA production and also systemic IgG production via oral, intranasal or parenteral route (12–14). CT also promotes innate immune response by enhancing antigen presentation by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), like dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages (15). However, the direct effect of CT on T cells has not been well defined. Several studies showed that CT suppresses T cell activation and proliferation (16–18), as well as that Th1 response but not Th2 response, is sensitive to the inhibition by CT (19, 20).

In the present study, we are curious whether CT can modulate Th17 responses. Thus, we carried out the CT treatment on isolated human peripheral blood (PB) CD4+ T cells and also on naïve T cells under Th17-polarizing culture conditions. Surprisingly, we found that CT significantly up-regulates IL-17A from CD4+ T cells whereas IFN-γ is suppressed and IL-4 is only slightly increased. In addition, the addition of cAMP analogs mimicked the CT effect on IL17A induction, thus suggesting the involvement of cAMP-signaling pathway in the regulation of IL17A production. Since CT and cAMP had been considered as a suppressor of T cell function, our data indicated that, instead of suppression, CT and cAMP favor the generation of Th17 responses.

Materials and Methods

Purification of total CD4+, naïve CD4+ T lymphocytes and specific T helper subsets from adult human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

The use of human cells in the study was periodically reviewed and approved by the University Human Subject Research Review Committee. PBMCs were purchased from Allcells. LLC. According to manufacturer’s protocol, total CD4+ T cells are positively selected from PBMCs using magnetic CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) or negatively selected using the Human CD4+ T cell enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technology). The purity of CD4+ T cells is 98–99% as confirmed by using FACScan (BD Biosciences). Human naïve CD4+ T cells were negatively selected using the Naïve CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of isolated naïve CD4+ T cells were confirmed as >95% on a FACScan when stained with APC-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD4 (Biolegend), FITC anti-CD45RA (BD Biosciences), APC anti-CD25 (Biolegend) and PE anti-CCR7 antibodies (eBioscience). Naïve T cells, CXCR3+/CCR6− cells (enriched Th1 cells), CXCR3−/CCR6+ cells (enriched Th17 cells), and CXCR3+/CCR6+ cells (enriched Th1/17 cells) were also isolated by sorting on a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). The purity of each subsets were confirmed as 96~99%. The following antibodies were used: Brilliant Violet (BV) 650 anti-CD4, Alexa Fluor (AF) 700 anti-CD45RA, BV570 anti-CD45RO, BV421 anti-CCR7, AF488 anti-CXCR3, PE anti-CCR6 (all from Biolegend).

Cell culture and differentiation

CD4+ T cells were cultured for two to four days in serum-free X-VIVO15 medium (Lonza) along with beads coated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibody (CD3/CD28 bead; 10 cells per bead; DynaBeads Human T-Activator, Invitrogen). Th17 polarizing cytokines, IL-1β (10ng/ml) and IL-23 (50ng/ml), as well as other cytokines, IL-2 (10ng/ml), IL-6 (20ng/ml), IL-10 (10ng/ml), IL-12 (10ng/ml), IFN-γ (100ng/ml) and TNF-α (20ng/ml), were added to the culture as indicated. Cytokine were purchased from R&D systems. CT (List Biological Laboratories), Forskolin (FK; Calbiochem), N6, O2-Dibutyryl-cAMP (db-cAMP; Calbiochem), Prostaglandin E2, (PGE2; Calbiochem), and 3-Isobutyl-1-Methylxanthine (IBMX; Sigma) were added at various concentrations to the culture media as indicated.

Naïve CD4+ T cells were activated with CD3/CD28 beads under Th0 (IL-2) or Th17-polarizing media (IL-1β/IL-23) in the presence or absence of CT. After six-day culture, Dynabeads were removed with a magnet and cells were expanded in media supplemented with IL-2 for three days.

Cytokine production assay and intracellular cAMP assay

IL-17A and IL-17F protein were detected by the Human IL-17 and IL17F DuoSet (R&D systems) and other cytokines, GM-CSF, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, were detected by using Invitrogen Human Cytokine 10-plex panel on the Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer’s protocol. CD4+ T cells were stimulated with CT-B, CT, PGE2 for one hour under CD3/CD28 activation. The cAMP levels of cell lysate were measured by using the cAMP Complete ELISA kit (Enzo Life sciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Intracellular staining

Treated CD4+ T cells were re-stimulated for five hours with TPA (50ng/ml, Cell Signaling) and ionomycin (1μM, Cell Signaling) in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Bioscience). Cells were then processed for intracellular staining with BD Cytofix/CytoPlus (BD Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Antibodies (Abs) used in this experiment were AF700 anti-IFNγ (BioLegend), FITC anti-IL17A (eBioscience), PE anti-IL17F (eBioscience), and AF647 anti-IL22 (eBioscience) for 30 min at 4°. Samples were assayed on a FACScan (BD Biosciences) and data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol according to the manufacturer’s instruction. SYBR Green Quantitative real-time PCR (Roche) was carried out to quantify the levels of cytokine expression after normalization with the housekeeping gene, GAPDH. The primers were designed by Primer 3 or previously described (1, 21) and were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Generation and site-directed mutagenesis of IL-17A promoter-luciferase reporter plasmids

A DNA fragment containing the proximal 229 bps of the IL-17A promoter region from the translation start sites was amplified from genomic DNA of human primary CD4+ T cells by PCR. The amplified product was sub-cloned into a pGL3 vector (Promega) with firefly luciferase reporter gene to generate pGL3-IL17A_Luc plasmid (IL17p/WT). The two individual cAMP-responsive elements (CREs) in the IL-17A promoter construct, CRE1 (−183~−178) and CRE2 (−111~−104) were mutagenized by using the QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). The resulting CRE constructs were termed IL17p/CREmt (mutations on both CRE sites). The authenticity of the clone was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The primer sequences used in this experiment are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Reporter gene transfection assay in activated CD4+ T cells and Jurkat cells

CD4+ T cells were activated with plate-coated anti-CD3 antibodies and soluble anti-CD28 antibodies for 16–20 hours. Activated cells were transfected with indicated plasmids together with Renilla Luciferase expression vector pRL-CMV (Promega) using the nucleofector kit for stimulated human T cells (Amaxa). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were further activated with CD3/CD28 beads and treated with CT as indicated. Jurkat cells were transfected with indicated plasmids and Renilla pRL-TK (Promga) using Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, cells were treated with 10 ng/ml CT together with TPA and ionomycin (Cell Signaling) for 5 hours. Cell extracts were lysed and luciferase activity was quantified in triplicate using Dual-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative IL-17A promoter activities were expressed as relative luciferase units after normalization to the internal control, Renilla luciferase activity. The results were averaged from triplicate wells of three separate experiments.

Statistics

P value was determined using two-tailed Student’s t test and multiple groups were analyzed using One-way ANOVA. P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Results

Direct stimulation of IL-17A production in CD3/CD28-activated PB CD4+ T cells by CT

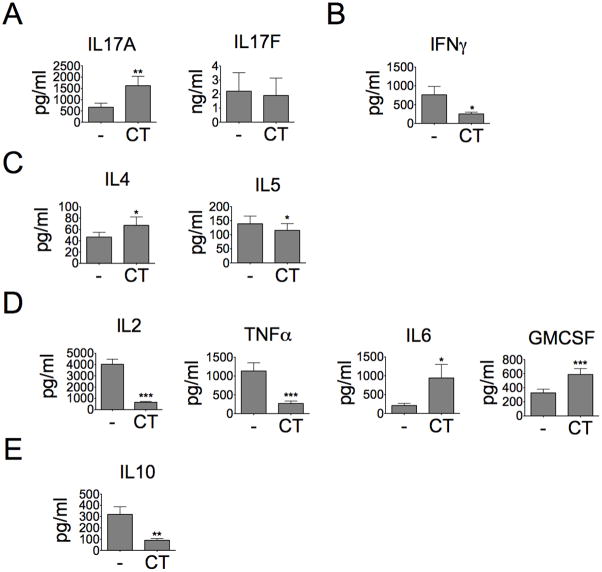

CT is a potent mucosal immunomodulator and also known to induce Th17 response in experimental animals (22, 23). However, it is unclear whether CT can directly regulate IL-17A production from human CD4+ T cells. Total PB CD4+ T cells were stimulated with CT for three days under CD3/CD28 activation. We found that CT enhanced IL-17A production by ~2.5-fold but slightly decreased IL-17F production in stimulated CD4+ T cells cultured under the non-polarizing condition (Fig. 1A). As for other cytokine expression, CT strongly inhibited IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2 and IL-10 production but not IL-4 and IL-5 (Fig. 1B–E). Interestingly, CT also induced GM-CSF production by ~1.8-fold (Fig. 1D), which was reported as one of Th17 pathogenic cytokines (4). Our results were consistent with prior reports that showed the inhibition of Th1 cytokines and IL-10 by CT (18, 20); however, Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, was not sensitive to the treatment of CT (19, 20). We even observed a slight increase of IL-4 production among some of CD4+ T cell preparations treated with CT.

Figure 1. CT directly induces IL-17A production but decreases Th1 cytokines from stimulated CD4+ T cells.

Total CD4+ T cells were stimulated with or without CT (10ng/ml) for three days under CD3/CD28 activation (10 cells per bead). A, Culture supernatant was analyzed for IL-17A and IL-17F protein production by ELISA (n=7, *p<0.05). (B) Th1 cytokines; (C) Th2 cytokines, (D) pro-inflammatory cytokines; (E) anti-inflammatory cytokines, were detected by using the kit of Invitrogen Human Cytokine 10-plex panel (n≥7, *p<0.05).

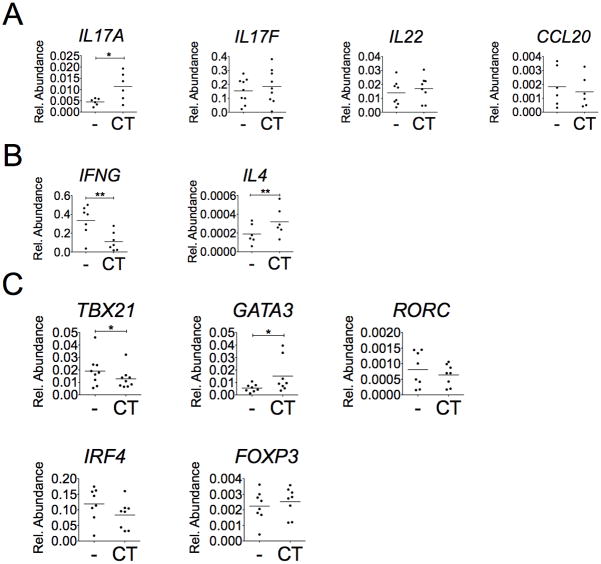

To examine if the changes in cytokine production are also reflected at mRNA levels, RNA were isolated from these cultures 48 hours after CT treatment. As shown in Fig. 2A, CT treatment increased mRNA levels of IL17A by ~2.5-fold; while CT treatment did not enhance the expression of other Th17 cell-associated cytokine genes, such as IL17F, IL22, and CCL20. RORγt and IRF4 are two Th17-lineage-specific transcriptional factors. RORγt is the major transcription factor in Th17 cell differentiation to induce IL-17A production (24); IRF4 has been reported to induce both IL-4 and IL-17 production (25, 26). However, the mRNA levels of RORC and IRF4 in CD4+ T cells were not affected by the treatment of CT (Fig. 2C). Regarding other Th-associated transcriptional factor genes (Fig. 2C), CT had no effect on FOXP3 expression, but it decreased mRNA levels of TBX21 expression but slightly increased GATA3 expression. These last two transcriptional factor expressions are consistent with the levels of the expression of their downstream cytokine genes, IFNG and IL4 expression, respectively in the study (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. CT increases IL17A, IL4, and GATA3 mRNA expression but decreases IFNG and TBX21 expression.

CD4+ T cells were treated with or without CT (10ng/ml) for 2 days under CD3/CD28 activation and total RNAs of cells were collected. The expression of (A) Th17-associated genes, (B) Th1&Th2-associated genes, and (C) transcription factors were examined by SyBr Green real-time PCR assay (n≥6, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

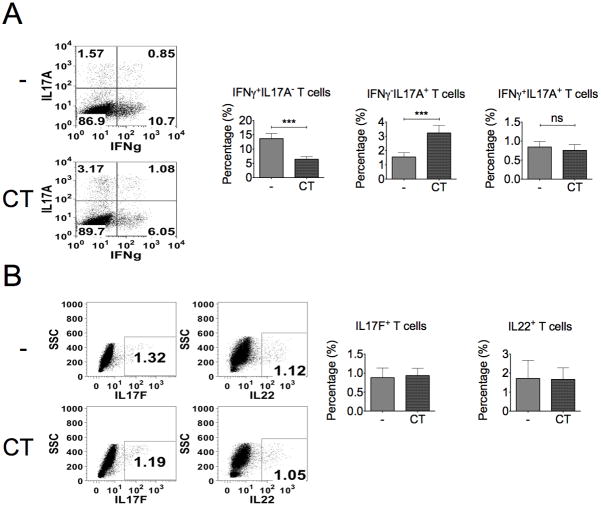

To characterize the change in cell population, especially with different cytokine expression, CT-treated cultures were analyzed by flow cytometry staining with anti-IFNγ, anti-IL17A, anti-IL17F, and anti-IL22 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3, CT decreased the percentage of IFNγ+IL-17A− and did not change in IFNγ+IL-17A+ populations, but increased IFNγ−IL-17A+ population after 4-day treatment (Fig. 3A). In contrast, there is no change in the percentage of total IL-17F+ or IL-22+ T cells (Fig. 3B). Therefore, CT selectively enhances IL-17A production but constrains IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. The percentage of IL-17A+ T cells is increased by the treatment of CT.

CD4+ T cells were cultured with or without CT for 4 days and re-stimulated with TPA (50ng/ml) and ionomycin (1μM) for 5 hours. Intracellular staining for IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 expression in T cells was examined by flow cytometry. A, Data represent the percentage of IFNγ +IL-17A−, IFNγ−IL-17A+ and IFNγ+IL-17A+ cells. B, Data represent the total percentage of IL17F+ and IL-22+ cells (n≥3, ***p<0.001).

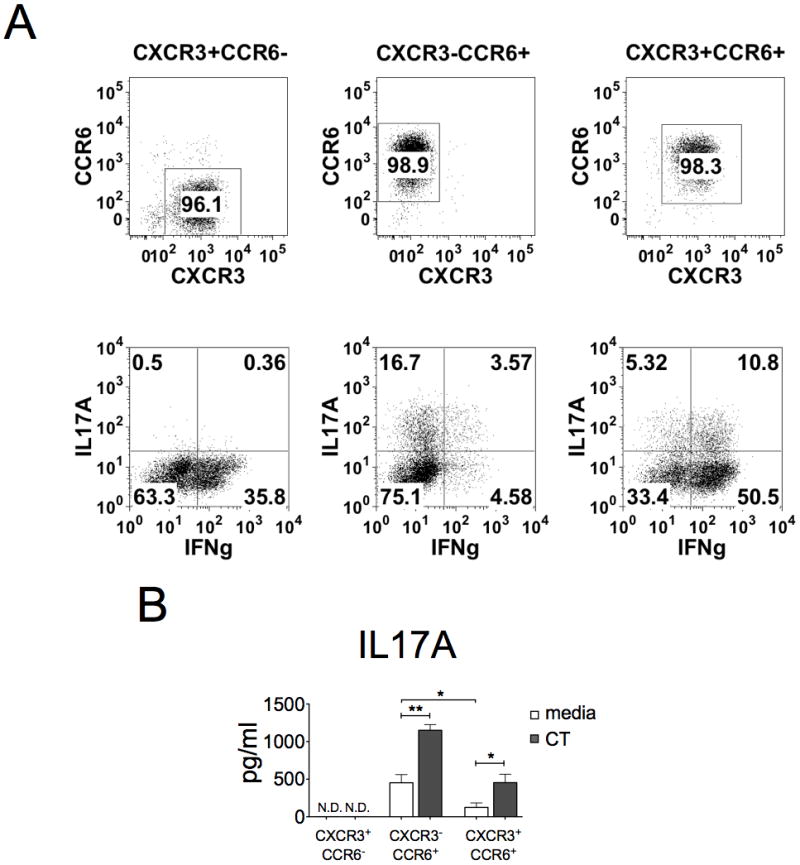

CT induces more IL-17A production from lineage-committed Th17 or Th1/17 cells but not from Th1 cells

Since CT caused the decrease of IFNγ+ but the increase of IL-17A− population, we first examine whether CT converts non-Th17 cells to Th17 cells or CT directly acts on Th17 cells. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 is expressed primarily on activated T cells and NK cells, especially preferentially expressed on Th1 cells (27, 28). It has been reported that CCR6 is predominately expressed on Th17 cells (29–31). Using antibodies specific to these two receptors, we isolated unstimulated Th1, Th17 and Th1/Th17 hybrid populations (32). The sorted Th subsets separately carry CXCR3+CCR6− (enriched Th1), CXCR3−CCR6+(enriched Th17), and CXCR3+CCR6+ (enriched Th1/17) surface chemokine receptors (Fig. 4A, upper panels). Further flow cytometric analysis of these subtypes confirmed their specificity of cytokine expression for IFNγ, IL-17A, and both cytokines (IFNγ/IL-17A), as related to Th1, Th17 and Th1/Th17 subtypes, respectively (Fig. 4A, lower panels). Treatments of these isolated subtypes of cells with CD3/CD28 activation have shown that CT could further enhance IL-17A production from Th17 and Th1/Th17 cells, but not from Th1 cells (Fig. 4B). These results support the notion that CT could only enhance IL-17A production from T cells that are capable of secreting IL-17A.

Figure 4. CT only enhances IL-17A production from differentiated Th17 subset.

Cells were sorted with CCR6 and CXCR3 surface marker to enriched Th1 (CXCR3+CCR6−), Th17 (CXCR3−CCR6+), and Th1/17 (CXCR+CCR6+). A, The purity (upper panels) and cytokine profile (lower panels) of sorted T cells were determined by using FACScan. Cells were activated with CD3/CD28 beads for three days, re-stimulated with TPA (50ng/ml) and ionomycin (1μM), and then stained with anti-IL17A and anti-IFNγ antibodies. Data represent one from three experiments. B, The IL-17A levels in cultured supernatant were examined after 3-day activation in the absence or presence of CT (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

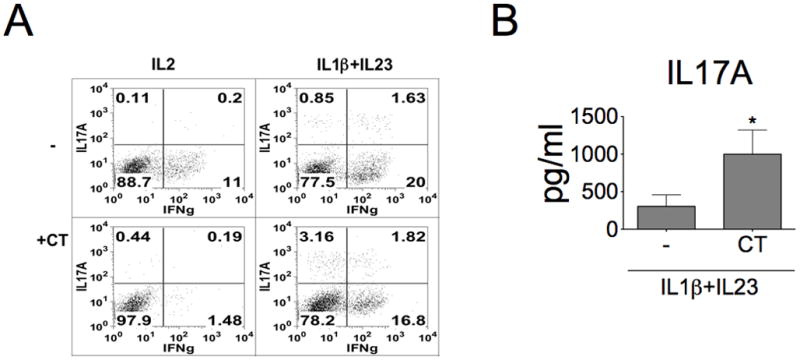

CT promotes further IL-17A production from naïve CD4+ T cells that were cultured under Th17-polarizing condition

In addition to enhancing the effector function of Th17 cells, CT may also promote Th17 cell differentiation to enhance the overall IL-17A production. To test this possibility, naïve CD4+ T cells were differentiated or not differentiated to Th17 cells under IL-1β and IL-23 supplemented or un-supplemented culture condition, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5A, flow cytometric analysis has shown a small increase of IL-17A-producing cells with a big drop of IFNγ-producing cells by CT in non-polarizing (Th0) naïve CD4+ T cell culture. In Th17 polarizing culture condition with IL-1β and IL-23 treatment, CT treatment enhanced more IL-17A-producing cells, but not the IFNγ-producing cell population. These results are consistent with the enhancement of IL-17A production in this polarized subset of cells activated by anti-CD3 treatment (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that CT alone has a minimal effect on Th17 cell differentiation from naïve CD4+ T cells under non-polarizing condition. However, this CT effect is further synergized with IL-1β/IL-23 polarized condition and resulted in more IL-17A producing cells and IL-17A production from activated CD4+ T cells.

Figure 5. CT promotes Th17 differentiation from naïve T cells under Th17-polarizing condition.

A, Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from human peripheral blood and differentiated under IL-2 alone or Th17-polarizing culture condition (IL-1β + IL-23 co-treatment) in the presence or absence of CT for 6 days and then rested in IL-2 (10 ng/ml) supplemented condition for additional 3 more days. Cells were then re-stimulated with TPA and ionomycin, and stained with anti-IL-17A and anti-IFNγ antibodies. Data represent one from three experiments. B, Effects of CT on IL-17A production from naïve CD4+ T cells cultured under Th17-polarizing culture condition (IL-1β + IL-23 co-treatment). These differentiated cells were re-stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 2 days. The IL-17A production in cultured supernatants was examined (n=4, *p<0.05).

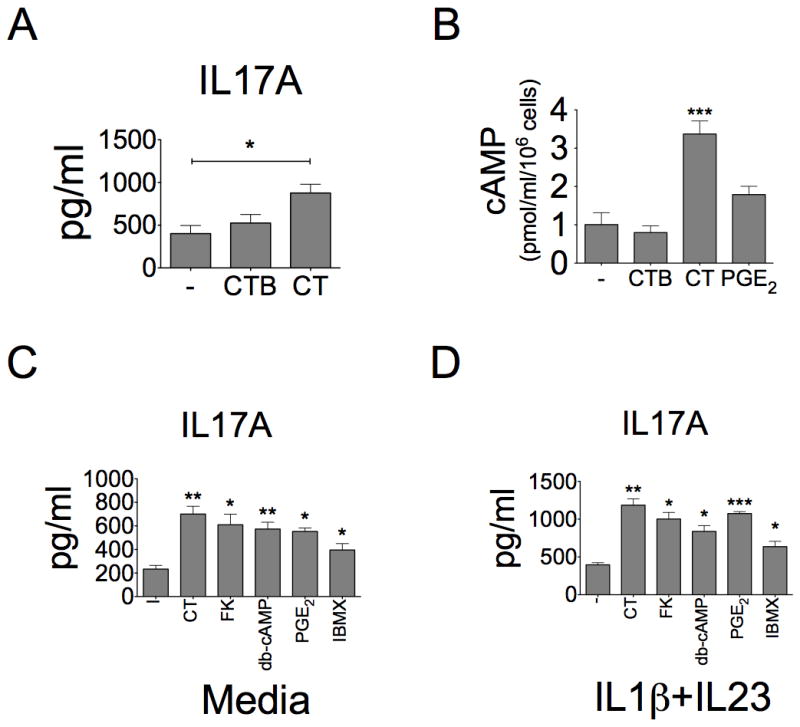

CT-induced IL-17A production is cAMP-dependent

The main biochemical consequence caused by CT is the sustained increase in intracellular cAMP, due to the constitutive activation of adenylate cyclase by CT-A subunit, which relies on the binding of CT-B to the cell surface in order to exert its function (10). To elucidate which CT subunits are responsible for the IL-17A induction, we compared the ability of CT and CT-B in the induction of IL-17A. As expected, CT-B alone did not effectively increase IL-17A production (Fig 6A). This result indicates that CT-A is required for the increase of IL-17A in T cells. We also measured the intracellular cAMP levels of CD4+ T cells after treated with CT-B or CT. As shown in Fig. 6B, the intracellular cAMP levels were increased by CT but not by CT-B. These results suggest that it is CT-A upon the translocation to exert its effect on the elevation of both the cAMP levels and IL-17A production.

Figure 6. Enhancing IL-17A production by cAMP-stimulating agents.

A, T cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 beads and treated with CT (10ng/ml) or CTB (10ng/ml). IL-17A production was examined in cultured supernatants from media, CT- or CTB-treated cells (n=5, ***p<0.001). B, Intracellular cAMP levels were examined in cell lysate from T cells by ELISA after one-hour treatment of CTB (10ng/ml), CT (10ng/ml) or PGE2 (1μM) (n=3, ***p<0.001). C–D, CD4+ T cells were treated with Forskolin (FK, 3μM), dibutyl-cAMP (db-cAMP, 100μM), IBMX (100μM) and PGE2 (1μM) for 3 days under (C) Th0 or (D) Th17-polarizing conditions. The IL-17A production in culture supernatants was assayed by ELISA (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, compared to “-” group). The “-” group means that cells were not treated by any cAMP agents.

Next, we examined whether the IL-17A induction by CT is due to the elevation of intracellular cAMP levels. Total CD4+ T cells were treated with various cAMP-elevating agents for 3 days under CD3/CD28 activation. The treatment of forskolin, which directly activates adenylyl cyclase to induce intracellular cAMP, increased IL-17A production (Fig. 6C). A similar result was observed when cells were treated with db-cAMP (cell permeable cAMP). We also used a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, IBMX, to see if the treatment could increase intracellular cAMP levels by blocking its degradation and resulted in an enhancement of IL-17A production. The addition of IBMX also slightly increased IL-17A production. We also found that CT and these cAMP-elevating agents synergized with IL-1β/IL-23 polarizing condition to enhance more IL-17A production (Fig. 6D). In summary, all cAMP-elevating agents can increase IL-17A production either under non-polarizing or Th17-polarizing condition.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has dual roles in anti-inflammation and pro-inflammation. Several reports also suggest that PGE2 regulates mouse and human Th17 function through cyclic AMP (33, 34). Therefore, we also examined the effect of PGE2 on CD4+ T cells in our system and the results showed that PGE2 also increased cAMP (Fig. 6B) and IL-17A production under non-polarizing (Fig. 6C) or Th17-polarizing (Fig. 6D) conditions. In addition, we have also looked into the similarity of the effects of CT and PGE2 treatments on various cytokine productions by CD4+ T cells. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. S1, both CT and PGE2 have a similar trend of effects on the production of GM-CSF, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10 in this CD4+ T cell system while this similarity was not seen in CT-B and control treatments. These results further confirm both CT and PGE2 enhance IL-17A production and alter other cytokine production via a common cAMP-dependent pathway.

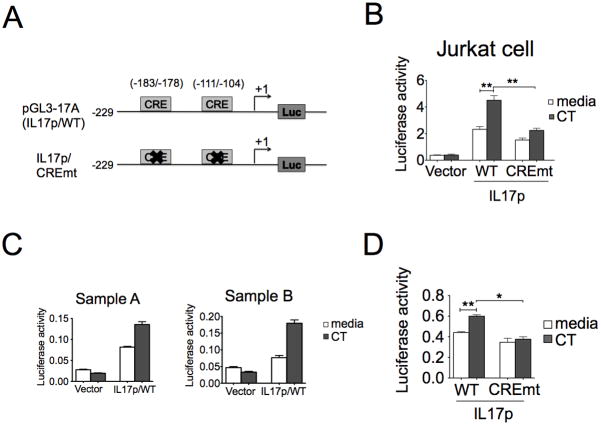

CT also stimulates IL-17A promoter activity in Jurkat cells and primary CD4+ T cells via cis-CRE elements

In addition to cAMP signaling, our data also indicates that CT regulates IL-17A production at the mRNA level (Fig 2A). To examine whether the effect of CT on IL-17A expression is due to transcriptional activation, a study of the CT effect on the IL-17A promoter activity was conducted both in Jurkat cells and primary CD4+ T cells using transient transfection approach with pGL3-IL17A construct. As shown in Fig. 7, CT increased the luciferase activity of IL-17A promoter construct in both Jurkat cells (Fig. 7B) and stimulated CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. CT directly enhances the IL-17A promoter activity dependent of cis-element CRE.

A, A schematic representation of the hIL17A promoter depicting cAMP-responsive element motifs used for wild type and mutated promoter constructs. B, Jurkat cells were transfected with indicated plasmids (vector, IL17p/WT, and CREmt) and pRL-TK using lipofectamine 2000. One day after transfection, transfected cells were treated with CT for four hours under the stimulation of TPA and ionomycin and the luciferase activity were measured. Luciferase activity was displayed as relative activity normalized with Renilla luciferase activity. Data represent three independent experiments (n=3, **p<0.01). C–D, Primary T cells were stimulated for 16–18 hours and nucleofected individually with indicated plasmids (vector, IL17p/WT, and CREmt) and pRL-CMV. After 6hr recovery, cells were treated with CT for extra 18 hours under CD3/28 activation. Cell lysate were examined by luciferase reporter assay after the restimulation with TPA and ionomycin for four hours (D, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

This IL-17A promoter construct contains two putative cAMP-responsive elements, CRE1 (-183~-178) and CRE2 (−111~−104). To further elucidate the role of CRE motifs in the transcriptional regulation of IL-17A gene, we generated one luciferase expression construct containing both mutated CRE1 and CRE2 termed IL17p/CREmt (Fig. 7A). The data showed that mutation of both CRE motifs of IL-17A promoter significantly reduced the responsiveness to CT (Fig. 7B and 7D). Taken together, our results clearly demonstrate that CRE motifs are essential to the response of IL-17A promoter to CT.

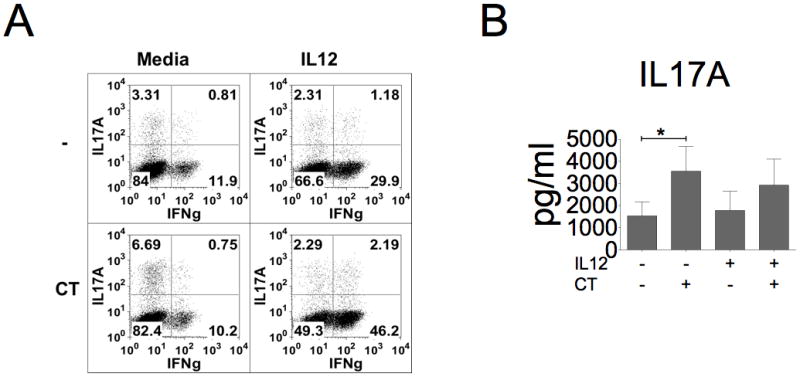

Exogenous cytokine effects on CT-induced IL-17A production

Our data showed that CT inhibited IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α production (Fig. 1). In addition, IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ have been reported to suppress Th17 responses. Therefore, it is possible that the enhancement of IL-17A is due to the decrease of other cytokines. To investigate whether the IL-17A induction by CT is due to bystander effect from other Th cells, IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ and also TNF-α were separately added to the culture media during the CT treatment. None of them can block the increase of IL-17A by CT. We also observed the increase of IL-6 in some samples. However, the addition of IL-6 or pre-treatment of anti-IL-6 antibodies did not change the IL-17A induction by CT either (Supplementary Fig. S2).

CT has been also reported to suppress IL-12 production from DCs and in experimental animals and CT also suppresses Th1 differentiation (35–37). In addition, IL-12 promotes the transition of Th17 to Th1/Th17 or Th1 cells (29, 38). To address if IL-12 may interfere CT-induced Th17 response, we carried out a combined treatment of CT and IL-12 on CD4+ T cells. As shown in Fig. 8A, flow cytometric analysis revealed that IL-12 could directly promote more IFN-γ+ T cells in the absence of CT, while had no effect on IL-17A+ T cell population. However, under CT treatment, IL-12 blocked the increase of IL-17A+ T cell population but promoted more IFN-γ+ T cells. Despite the changes in cell populations, IL-17A production in the secreted media from the cultures with or without CT was not significantly affected by IL-12 (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that IL-12, likes other examined cytokines had no direct effects on CT-induced IL-17A production, but it could change T cell population toward more Th1 subset of cells.

Figure 8. IL-12 modulates the effect of CT on T cells.

Cells were treated with the combination of CT (10 ng/ml) and IL-12 (10 ng/ml) for three days and then re-stimulated with TPA and ionomycin. A, Re-stimulated T cells were stained with anti-IL-17A and anti-IFNγ antibodies. Data shown represent three independent experiments with similar results. B, IL-17A production was assessed by ELISA (n=6, *p< 0.05).

Discussion

Th17 cell differentiation is mediated by the integration of signals from T cell receptor, costimulatory molecules, and cytokines. An increasing number of studies also showed that microbial components regulate Th17 differentiation directly or via the activation of APCs (6, 8). In this study, we demonstrated a novel function of CT to enhance IL-17A production from human PB CD4+ T cells and the generation of Th17 cells. The mechanism of CT-induced IL-17A production is mediated via cAMP-dependent pathway and occurs at the transcriptional level. Our data also indicated that CT exclusively activates the expression of IL-17A and its promoting cytokines, IL-6 and GM-CSF. Since various cAMP analogs can have the similar CT effects, these results suggest the importance of cAMP signaling pathway in mediating Th17 cell differentiation.

Unlike IL-17A expression, CT did not increase the expression of other Th17-associated cytokine genes, such as IL-17F and IL-22. The difference in the regulation of Th17 cytokines has also been reported in other studies. For instance, TGF-β suppresses IL-22 expression but enhances IL-17A expression (39). Furthermore, it has been shown that Th17 cytokines function alike but differently in physiological conditions and disease pathogenesis (40). IL-17A and IL-17F KO mice have different disease outcomes in experimental models of allergic encephalitis and allergic airway diseases (41). These studies suggest that, in response to various environmental stimuli, Th17 cells secrete various combinations of cytokines to execute their function properly. Our study defined that CT is one of these immunomodulators to selectively enhance IL-17A production from Th17 cells.

Besides IL-17A, CT also induced GM-CSF production in T cells. GM-CSF is an activator for the development of DCs and has been used as a cytokine adjuvant in the vaccine development (42, 43). Furthermore, GM-CSF is also involved in Th17-mediated autoimmune encephalomyelitis. IL-23 has been reported to drive GM-CSF expression by Th17 cells and then GM-CSF activates DCs to secrete more IL-23. This IL-23-GM-CSF circuit enhances Th17 responses (4, 44, 45). Whether GM-CSF secreted from CT-treated T cells also has this IL-23-GM-CSF loop to enhance Th17 cell function in vivo needs to be clarified.

We also studied the underlying mechanism of CT-modulated IL-17A production in T cells. Our data suggest that CT-A subunit plays the major role in the induction of IL-17A, which subunit has ADP-ribosylating activity to activate adenylate cyclase. In addition, we found that cAMP-elevating agents, such as forskolin and db-cAMP, mimic the CT effect on IL-17A stimulation. This result suggests that higher intracellular cAMP levels in T cells promote IL-17A production. Interestingly, naturally occurring T regulatory (Treg) cells also have higher levels of endogenous cAMP than conventional CD4+ T cells and mediate their suppressive function by conferring cAMP to effector T cells through gap junctions (46). Moreover, the cAMP signaling in T cells has also been reported to suppress T cell activation and proliferation. However, our study suggested a new role of cAMP in the immune regulation, rather than immunosuppression. Whether endogenous cAMP levels determine different fates of Th cells and whether cAMP-dependent pathway regulates the balance of Treg and Th17 cells are rarely explored and important in immune regulation.

To further explore the molecular nature of CT-induced IL-17A expression, we also conducted promoter-reporter gene transfection studies in Jurkat cells and primary T cells. We observed a CT-induced IL-17A promoter-reporter activity in these transfected cells. This result supports an increased transcriptional activity as a mechanism for IL-17A production. We further demonstrated that CRE motifs on IL-17A promoter are responsible for this CT-induced promoter activity. However, the sequence around these CRE sites can be occupied with multiple transcription factors, such as RORγt, CREMα, and BATF (47). The transcriptional factors RORγt (24, 48) and CREMα (49) have been reported to bind to the region across the CRE2 (−111~−104) sequence of IL-17A promoter. RORγt is the major transcription factor of Th17 differentiation and induces IL-17A expression via direct binding to the promoter. In our study, CT did not enhance mRNA levels of RORγt. In addition, the siRNA knockdown of RORγt and the pretreatment of RORα/γt inverse agonist SR1001 did not affect CT-induced IL-17A production (data not shown). This result indicates that CT may induce IL-17A production via a transcriptional activation but RORγt-independent pathway. However, whether CT-induced IL-17A expression is dependent on BATF, CREMα or other transcription factors needs to be explored.

PGE2 is one of the physiological molecules using cAMP as its secondary messenger. PGE2 is a negative regulatory molecule in the immune activation. It has been thought to inhibit the function of neutrophils, monocytes, and also IFN-γ production by Th1 cells (50). However, some evidence also shows that PGE2 also has pro-inflammatory properties in inflammatory bowel disease (51) and collagen-induced arthritis (52). In-vitro culture of CD4+ T cells with PGE2 showed that PGE2 enhances IFN-γ expression and Th17 expansion in certain conditions (33, 34). In our system, like CT, PGE2 inhibited IL-2, IL-10 and TNF-α production but its effect on IFN-γ is not consistent among samples.

A variety of cytokines and other immunomodulators are expressed at the site of inflammation and their crosstalk directs Th cells to preform specific effector functions. In our study, we found that IL-6 was increased but IFN-γ and IL-10 was decreased. This result indicates that the CT-induced response favors Th17 cells although the addition of these cytokines into T cells culture media did not change the ability of CT on IL-17A induction. Besides, we also examined cytokines that favor Th17 development and the one that favors Th1 development in our study. Our data showed that CT had a synergistic effect with IL-1β plus IL-23 to promote more IL-17A production. In addition, we observed that IL-12 could abrogate the ability of CT to inhibit Th1 responses. However, we still detected more IL-17A production from CT-treated cells even when IL-12 was added. Interestingly, the increase in the percentage of IL-17A+ cells is constrained by IL-12. It is likely that IL-12 changes the proliferative ability of different Th cells or IL-12 directly constrains new Th17 cell generation. This finding emphasizes the invincible role of CT on IL-17A stimulation and also indicates that the crosstalk among different modulators is critical to determine the outcome of immune responses.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that cholera toxin is a powerful agent to determine the outcome of T cell response. Therefore, more studies on other bacterial toxins in T cells can be executed to discover new modulators that can directly promote or suppress specific Th response. The exploration of the mechanism triggered by toxins also provides an attractive target to develop new therapeutic strategies of immunemediated diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This Study was supported by HL077902, HL096373 and HL097087 from NIH

We thank Dr. Judy Van de Water, Marjannie Eloi and Lori Haapanen from University of California, Davis for technical support of the Luminex assay and Dr. Elva Diaz for providing nucleofector device. We appreciate that Abbie Spinner from California National Primate Research Center helped on cell sorting and that Shannon Lee from UC Davis helped on the promoter activity assay. We also thank Dr. Chen-Chen Lee from China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan for her suggestion on our manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration: The authors have no direct financial interest or relationship to the subject matter of this report.

References

- 1.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Basham B, Smith K, Chen T, Morel F, Lecron JC, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ, McClanahan TK, Bowman EP, de Waal Malefyt R. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong C. TH17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nature reviews Immunology. 2008;8:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nri2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirota K, Yoshitomi H, Hashimoto M, Maeda S, Teradaira S, Sugimoto N, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ito H, Nakamura T, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. Preferential recruitment of CCR6-expressing Th17 cells to inflamed joints via CCL20 in rheumatoid arthritis and its animal model. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:2803–2812. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, Yan Y, Cullimore M, Safavi F, Zhang GX, Dittel BN, Rostami A. The encephalitogenicity of T(H)17 cells is dependent on IL-1- and IL-23-induced production of the cytokine GM-CSF. Nature immunology. 2011;12:568–575. doi: 10.1038/ni.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffen SL. Recent advances in the IL-17 cytokine family. Current opinion in immunology. 2011;23:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGeachy MJ, McSorley SJ. Microbial-induced Th17: superhero or supervillain? Journal of immunology. 2012;189:3285–3291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aliahmadi E, Gramlich R, Grutzkau A, Hitzler M, Kruger M, Baumgrass R, Schreiner M, Wittig B, Wanner R, Peiser M. TLR2-activated human langerhans cells promote Th17 polarization via IL-1beta, TGF-beta and IL-23. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:1221–1230. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds JM, Pappu BP, Peng J, Martinez GJ, Zhang Y, Chung Y, Ma L, Yang XO, Nurieva RI, Tian Q, Dong C. Toll-like receptor 2 signaling in CD4(+) T lymphocytes promotes T helper 17 responses and regulates the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2010;32:692–702. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornef MW, Wick MJ, Rhen M, Normark S. Bacterial strategies for overcoming host innate and adaptive immune responses. Nature immunology. 2002;3:1033–1040. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanden Broeck D, Horvath C, De Wolf MJ. Vibrio cholerae: cholera toxin. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2007;39:1771–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walia K, Ganguly NK. Toxins of Vibrio Cholera and Their Role in Inflammation, Pathogenesis, and Immunomodulation. In: Ramamurthy T, Bhattacharya SK, editors. Infectious disease: Epidemiological and Molecular Aspects on Cholera. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu-Amano J, Kiyono H, Jackson RJ, Staats HF, Fujihashi K, Burrows PD, Elson CO, Pillai S, McGhee JR. Helper T cell subsets for immunoglobulin A responses: oral immunization with tetanus toxoid and cholera toxin as adjuvant selectively induces Th2 cells in mucosa associated tissues. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1993;178:1309–1320. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmucker DL. Efficacy of intraduodenal, oral and parenteral boosting in inducing intestinal mucosal immunity to cholera toxin in rats. Immunological investigations. 1999;28:339–346. doi: 10.3109/08820139909062267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama Y, Harabuchi Y. Intranasal immunization with lipoteichoic acid and cholera toxin evokes specific pharyngeal IgA and systemic IgG responses and inhibits streptococcal adherence to pharyngeal epithelial cells in mice. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2002;63:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bromander AK, Kjerrulf M, Holmgren J, Lycke N. Cholera toxin enhances antigen presentation. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1995;371B:1501–1506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imboden JB, Shoback DM, Pattison G, Stobo JD. Cholera toxin inhibits the T-cell antigen receptor-mediated increases in inositol trisphosphate and cytoplasmic free calcium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83:5673–5677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DK, Nau GJ, Lancki DW, Dawson G, Fitch FW. Cholera toxin discriminates between murine T lymphocyte proliferation stimulated by activators of protein kinase C and proliferation stimulated by IL-2. Possible role for intracellular cAMP. Journal of immunology. 1988;141:3429–3437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vendetti S, Patrizio M, Riccomi A, De Magistris MT. Human CD4+ T lymphocytes with increased intracellular cAMP levels exert regulatory functions by releasing extracellular cAMP. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2006;80:880–888. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munoz E, Zubiaga AM, Merrow M, Sauter NP, Huber BT. Cholera toxin discriminates between T helper 1 and 2 cells in T cell receptor-mediated activation: role of cAMP in T cell proliferation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1990;172:95–103. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson K, Nordstrom I, Czerkinsky C, Holmgren J. Differential effect of cholera toxin on CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ T cells: specific inhibition of cytokine production but not proliferation of human naive T cells. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2000;121:283–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin HJ, Lee JB, Park SH, Chang J, Lee CW. T-bet expression is regulated by EGR1-mediated signaling in activated T cells. Clinical immunology. 2009;131:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JB, Jang JE, Song MK, Chang J. Intranasal delivery of cholera toxin induces th17-dominated T-cell response to bystander antigens. PloS one. 2009;4:e5190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Datta SK, Sabet M, Nguyen KP, Valdez PA, Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Islam S, Mihajlov I, Fierer J, Insel PA, Webster NJ, Guiney DG, Raz E. Mucosal adjuvant activity of cholera toxin requires Th17 cells and protects against inhalation anthrax. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:10638–10643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002348107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahyi AN, Chang HC, Dent AL, Nutt SL, Kaplan MH. IFN regulatory factor 4 regulates the expression of a subset of Th2 cytokines. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:1598–1606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mudter J, Yu J, Zufferey C, Brustle A, Wirtz S, Weigmann B, Hoffman A, Schenk M, Galle PR, Lehr HA, Mueller C, Lohoff M, Neurath MF. IRF4 regulates IL-17A promoter activity and controls RORgammat-dependent Th17 colitis in vivo. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17:1343–1358. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto J, Adachi Y, Onoue Y, Adachi YS, Okabe Y, Itazawa T, Toyoda M, Seki T, Morohashi M, Matsushima K, Miyawaki T. Differential expression of the chemokine receptors by the Th1- and Th2-type effector populations within circulating CD4+ T cells. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2000;68:568–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 in T cell function. Experimental cell research. 2011;317:620–631. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Liotta F, Mazzinghi B, Parente E, Fili L, Ferri S, Frosali F, Giudici F, Romagnani P, Parronchi P, Tonelli F, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1849–1861. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh SP, Zhang HH, Foley JF, Hedrick MN, Farber JM. Human T cells that are able to produce IL-17 express the chemokine receptor CCR6. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:214–221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romagnani S, Maggi E, Liotta F, Cosmi L, Annunziato F. Properties and origin of human Th17 cells. Molecular immunology. 2009;47:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi RL, Rossetti G, Wenandy L, Curti S, Ripamonti A, Bonnal RJ, Birolo RS, Moro M, Crosti MC, Gruarin P, Maglie S, Marabita F, Mascheroni D, Parente V, Comelli M, Trabucchi E, De Francesco R, Geginat J, Abrignani S, Pagani M. Distinct microRNA signatures in human lymphocyte subsets and enforcement of the naive state in CD4+ T cells by the microRNA miR-125b. Nature immunology. 2011;12:796–803. doi: 10.1038/ni.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao C, Sakata D, Esaki Y, Li Y, Matsuoka T, Kuroiwa K, Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E2-EP4 signaling promotes immune inflammation through Th1 cell differentiation and Th17 cell expansion. Nature medicine. 2009;15:633–640. doi: 10.1038/nm.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boniface K, Bak-Jensen KS, Li Y, Blumenschein WM, McGeachy MJ, McClanahan TK, McKenzie BS, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ, de Waal Malefyt R. Prostaglandin E2 regulates Th17 cell differentiation and function through cyclic AMP and EP2/EP4 receptor signaling. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:535–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun MC, He J, Wu CY, Kelsall BL. Cholera toxin suppresses interleukin (IL)-12 production and IL-12 receptor beta1 and beta2 chain expression. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1999;189:541–552. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagley KC, Abdelwahab SF, Tuskan RG, Fouts TR, Lewis GK. Cholera toxin and heat-labile enterotoxin activate human monocyte-derived dendritic cells and dominantly inhibit cytokine production through a cyclic AMP-dependent pathway. Infection and immunity. 2002;70:5533–5539. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5533-5539.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veglia F, Sciaraffia E, Riccomi A, Pinto D, Negri DR, De Magistris MT, Vendetti S. Cholera toxin impairs the differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells, inducing professional antigen-presenting myeloid cells. Infection and immunity. 2011;79:1300–1310. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01181-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Chen D, Elson CO, Weaver CT. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity. 2009;30:92–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutz S, Noubade R, Eidenschenk C, Ota N, Zeng W, Zheng Y, Hackney J, Ding J, Singh H, Ouyang W. Transcription factor c-Maf mediates the TGF-beta-dependent suppression of IL-22 production in T(H)17 cells. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1238–1245. doi: 10.1038/ni.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Cytokine mediators of Th17 function. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:658–661. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang XO, Chang SH, Park H, Nurieva R, Shah B, Acero L, Wang YH, Schluns KS, Broaddus RR, Zhu Z, Dong C. Regulation of inflammatory responses by IL-17F. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:1063–1075. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ou-Yang P, Hwang LH, Tao MH, Chiang BL, Chen DS. Co-delivery of GM-CSF gene enhances the immune responses of hepatitis C viral core protein-expressing DNA vaccine: role of dendritic cells. Journal of medical virology. 2002;66:320–328. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nambiar JK, Ryan AA, Kong CU, Britton WJ, Triccas JA. Modulation of pulmonary DC function by vaccine-encoded GM-CSF enhances protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. European journal of immunology. 2010;40:153–161. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGeachy MJ. GM-CSF: the secret weapon in the T(H)17 arsenal. Nature immunology. 2011;12:521–522. doi: 10.1038/ni.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Codarri L, Gyulveszi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L, Suter T, Becher B. RORgammat drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nature immunology. 2011;12:560–567. doi: 10.1038/ni.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaeth M, Gogishvili T, Bopp T, Klein M, Berberich-Siebelt F, Gattenloehner S, Avots A, Sparwasser T, Grebe N, Schmitt E, Hunig T, Serfling E, Bodor J. Regulatory T cells facilitate the nuclear accumulation of inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) and suppress nuclear factor of activated T cell c1 (NFATc1) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2480–2485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009463108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schraml BU, Hildner K, Ise W, Lee WL, Smith WA, Solomon B, Sahota G, Sim J, Mukasa R, Cemerski S, Hatton RD, Stormo GD, Weaver CT, Russell JH, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. The AP-1 transcription factor Batf controls T(H)17 differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature08114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ichiyama K, Yoshida H, Wakabayashi Y, Chinen T, Saeki K, Nakaya M, Takaesu G, Hori S, Yoshimura A, Kobayashi T. Foxp3 inhibits RORgammat-mediated IL-17A mRNA transcription through direct interaction with RORgammat. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17003–17008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauen T, Hedrich CM, Juang YT, Tenbrock K, Tsokos GC. cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREM)alpha protein induces interleukin 17A expression and mediates epigenetic alterations at the interleukin-17A gene locus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:43437–43446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris SG, Padilla J, Koumas L, Ray D, Phipps RP. Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends in immunology. 2002;23:144–150. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheibanie AF, Yen JH, Khayrullina T, Emig F, Zhang M, Tuma R, Ganea D. The proinflammatory effect of prostaglandin E2 in experimental inflammatory bowel disease is mediated through the IL-23-->IL-17 axis. Journal of immunology. 2007;178:8138–8147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheibanie AF, Khayrullina T, Safadi FF, Ganea D. Prostaglandin E2 exacerbates collagen-induced arthritis in mice through the inflammatory interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2007;56:2608–2619. doi: 10.1002/art.22794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.