Abstract

Soft collagenous tissues that are loaded in vivo undergo crosslinking during aging and wound healing. Bio-prosthetic tissues implanted in vivo are also commonly crosslinked with glutaraldehyde. While crosslinking changes the mechanical properties of the tissue, the nature of the mechanical changes and the underlying microstructural mechanism is poorly understood. In this study, a combined mechanical, biochemical and simulation approach was employed to identify the microstructural mechanism by which crosslinking alters mechanical properties. The model collagenous tissue used was an anisotropic cell-compacted collagen gel, and the model crosslinking agent was monomeric glutaraldehyde. The collagen gels were incrementally crosslinked by either increasing the glutaraldehyde concentration or by increasing the crosslinking time. In biaxial loading experiments, increased crosslinking produced: (1) decreased strain response to a small equibiaxial preload, with little change in response to subsequent loading, and (2) decreased coupling between the fiber and cross-fiber direction. The mechanical trend was found to be better described by the lysine consumption data than by the shrinkage temperature. The biaxial loading of incrementally-crosslinked collagen gels was simulated computationally with a previously published network model. Crosslinking was represented by increased fibril stiffness or by increased resistance to fibril rotation. Only the latter produced mechanical trends similar to that observed experimentally. Representing crosslinking as increased fibril stiffness did not reproduce the decreased coupling between the fiber and cross-fiber directions. The study concludes that the mechanical changes in crosslinked collagen gels are caused by the microstructural mechanism of increased resistance to fibril rotation.

Keywords: collagen gel, crosslink, glutaraldehyde, biaxial mechanics

INTRODUCTION

Collagen is a fibrous protein that is a major structural component of extracellular matrix and connective tissue [1]. The basic monomeric unit of a collagen fibril is tropocollagen-a rigid rod-like molecule, about 2800A in length, with a central triple helical region of three alpha polypeptide chains and terminal disordered ends called telopeptides [2, 3]. In the extracellular environment, the tropocollagen molecules self-assemble by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, in a head-to-tail and laterally quarter-staggered arrangement, to form a collagen fibril [3]. The nascent collagen fibril, held together by non-covalent interactions, is not stable - the collagen molecules are free to slide past one another and the fibril is disrupted by variations in pH, ionic strength, temperature and by proteolysis [4]. However, following assembly, covalent crosslinking by the enzyme lysyl oxidase and to some extent, non-enzymatic crosslinking by glycation and nitration [5], stabilize the fibrils, conferring the high tensile strength characteristic of mature collagen fibrils. Abnormal crosslinking causes diseases such as Menke’s disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and a form of cutis laxa [4].

Most crosslinks in collagen fibrils are found between tropocollagen monomers [4]. They require the monomers to assemble into quarter-staggered arrays for their formation [6, 7]. Crosslinking is initiated after specific lysine and hydroxy-lysine residues in the non-helical telopeptides are converted into aldehydes by the enzyme lysyl oxidase [5]. The aldehydes spontaneously react with lysine, hydroxy-lysine or histidyl residues in the helical region of neighboring monomers. The resulting crosslinks possess Schiff base double bonds and are initially reducible with borohydride. With time, the reducible crosslinks convert into the complex non-reducible forms found in mature collagen tissues [8]. The non-reducible crosslinks are multi-valent (crosslinking multiple residues and possibly between collagen fibrils) and are responsible for the decreased solubility of collagenous tissues with aging.

We are interested in the effect of crosslinking on the mechanical properties of load-bearing tissues. For instance, some have found that crosslinking in healing myocardial infarcts is as important to regional and global left ventricular mechanics as the collagen content and alignment in the scar [9]. Crosslinking is used to improve the mechanical properties and in vivo stability of bio-prosthetic implants [10-12]. Crosslinked tissues typically show decreased extensibility in mechanical tests ex vivo. However there is no consensus on how these and other mechanical changes relate to the microstructure-level changes induced by crosslinking. Such a perspective is necessary to translate observations from ex vivo mechanical testing to the complex loading in vivo, to effectively treat pathologies of load-bearing tissues, and to design crosslinking procedures for bioprosthetic tissues that produce mechanical properties comparable to the original tissue.

The goal of this study is to understand the micro-structural mechanisms by which crosslinking changes the mechanics of collagenous tissues. As a model collagenous tissue, we used a cell-compacted, structurally anisotropic collagen gel [13, 14]. The collagen gel system is an in vitro reconstituted system that consists of interconnected collagen fibrils [15]. There is no contribution or complication from non-collagenous components as in a native collagenous tissue, and any change in mechanical properties can be attributed to mechanisms involving collagen fibrils and their arrangement [13, 16]. As a model crosslinking agent we used glutaraldehyde. Glutaraldehyde is commonly used to crosslink bio-prosthetic implants and for fixing tissue. It predominantly reacts with the lysines and hydroxy-lysines of collagen [17-19]. In the following study, we exposed collagen gels to increasing levels of crosslinking and measured resulting changes in biochemistry and mechanical properties. We then implemented potential microstructural mechanisms in a network model of collagen gels. We simulated biaxial loading in the ‘crosslinked’ collagen model to identify the microstructural mechanism that produced mechanical changes most similar to that observed experimentally.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of anisotropic cell-compacted collagen gels

The collagen gels were reconstituted from protease-extracted Type I bovine dermal collagen monomers (sold as PureColl, Allergan Inamed). These monomers typically lose the telopeptide region during the extraction procedure (Allergan Inamed, personal communication). Upon reconstitution to physiological pH, temp and ionic strength, the monomers form a hydrated, inter-connected and entangled assembly of collagen fibrils [20]. Contractile cells like fibroblasts, when present in the reconstitution mixture, compact the gel in a process similar to wound contraction [21]. In our experiments, two opposite sides of the gel were constrained prior to compaction, so that the compaction was anisotropic. It resulted in a flattened, tissue-like matrix with a predominant direction of collagen orientation.

The procedure for cell isolation and gel preparation are described in Knezevic et al [20]. Briefly, the monomeric purified bovine dermal collagen was mixed with an ice-cold solution of 0.2M HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) and 10X MEM (Life Technologies, MD) in the ratio 8.1.1. Primary rat adult cardiac fibroblasts (2nd passage) maintained in culture medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), 10% Neonatal Bovine Serum, 5% Fetal Bovine Serum, 0.2% Amphotericin B and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin) were harvested and mixed with the collagen solution in 1:4 ratio, to a final cell concentration of 200,000/ml per gel. We note that phenolphthalein-free DMEM was used in the cell and gel solutions to avoid interference with measurements of glutaraldehyde absorption.

The collagen gel solution was solidified in a square mold (Fig.1a). The mold was assembled by attaching an upper, circular piece to a lower, square base, using stopcock grease (Fisher Scientific, PA). The upper circular piece was 0.5” thick, with 6cm radius, and made of polysulfone (Tri-Star Plastic, NC). It had a central square 4cm×4cm cutout. The lower square base was 1/8” thick, and made of polycarbonate (Small parts, FL). Sixteen needles (29G from Henry Schein, NY) were placed upright within the central cutout, four on each side and approximately 0.5 cm from the edge of the mold (Fig.1a). The removable needles served two purposes: to act as boundary constraints for the anisotropic compaction of the gel, and to create holes in the gel for suture attachment to the biaxial stretching apparatus. The entire mold assembly was placed within a 100-mm petri dish and was coated with 2% BSA to prevent cells and gel from sticking. The mold assembly and treatments were performed under sterile conditions.

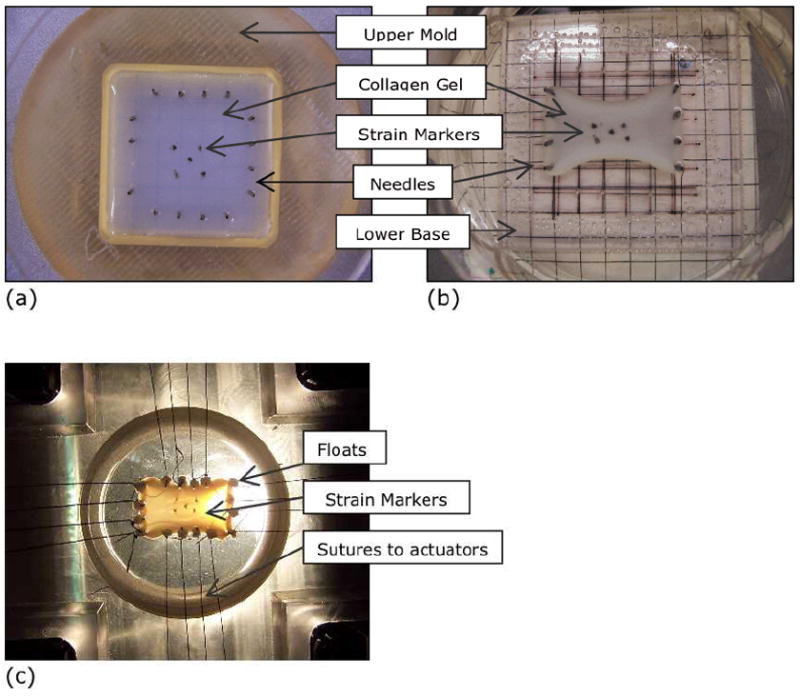

Fig.1.

(a) Gelation of collagen solution in mold. The mold consisted of a round upper polypropylene piece attached to a square lower base with vacuum grease. Removable needles were placed within the mold to leave holes in the gel after solidification. The mold setup was placed within a petri-dish. Strain markers were embedded in the gel before it solidified completely. (b) Anisotropic gel following two-days of cell-compaction. The upper piece of the mold was removed after the gel solidification stage in (a) to allow free media exchange. Two sets of needles on opposite sides were removed to present anisotropic constraints for cell compaction. The gel was incubated for 2 days, during which it was compacted in an anisotropic manner (c) Anisotropic crosslinked gel attached to biaxial loading device for testing. The compacted gels from (b) were exposed to the crosslinking solution and prepared for mechanical testing. Loops of silk thread were sutured along with polypropylene floats into the needle holes in the gel. The horizontal direction is the direction of predominant fiber orientation and is referred to the ‘fiber direction’. The vertical direction is referred to as the ‘cross-fiber’ direction.

10 ml of the cell/gel mixture was poured into the mold, and incubated for 2 hrs at 37°C to solidify the gel. Approximately 1 hour prior to complete solidification, 4 – 6 polyethylene chips (porous, coarse and blackened with India ink) were embedded in the gel as strain markers. After complete solidification of the gel, the upper mold piece and two sets of opposite pins were removed. The petri dish was filled with cell culture media (DMEM with 10% FBS, Ampho-B and Penicillin-Streptomycin) and returned to the 37°C incubator. The gel remained in the incubator for two days, during which the fibroblasts contracted the gel in an anisotropic manner (Fig.1b). Images of the gel were taken before and after the cell-compaction were used to quantify the anisotropic gel strain from compaction. A detailed study of the development of anisotropic fibril orientation with anisotropic gel compaction, can be found in Thomopoulos et al. [13, 14].

Fixation with glutaraldehyde

Prior to fixation, the gel was incubated and washed multiple times with 0.2M cold PBS, to remove components from the culture media that may interfere with readings of glutaraldehyde absorption. 8% purified glutaraldehyde in the monomeric form was obtained from Polysciences (Warrington, PA), and the solution was diluted to 0.6%, 0.06% or 0.006% w/v in 0.2M PBS. The collagen gel was exposed to 10ml of the glutaraldehyde solution for either 10min, 30 min, 1hr or 36 hrs. After fixation, the gels were washed thrice with 0.2M cold PBS and stored at 4°C for mechanical testing.

Each collagen gel in our experiment contains ~20.4 mg of collagen, and ~30 (hydroxy) lysines per 1000 amino acids (source: Allergan Inamed, CA). Therefore using 10 ml of 0.006%, 0.06% and 0.6% w/v glutaraldehyde solution per gel corresponds to crosslinking with ~1, 10 and 100 moles of glutaraldehyde per mole of (hydroxy) lysine. Typically, tissues are crosslinked with glutaraldehyde concentrations on the order of 0.6% w/v [22]. The collagen content of tissues being higher, the typical number of glutaraldehyde moles per lysine is ~10 in tissues, which is comparable to crosslinking collagen gels with 0.06% glutaraldehyde in our case.

MECHANICAL CHARACTERIZATION

Biaxial loading

Loops of 4.0 braided silk suture (Henry Schein, NY) were tied, along with hydrophobic polyethylene chips as floats, to each pair of adjacent holes in a gel (Fig.1c). Each suture loop was than put around the rotating wheels of the actuator of the biaxial testing apparatus. The biaxial apparatus is custom-built, as per the design in Sacks et al [23, 24], and was operated in the load-control mode for our experiments. Each actuator consists of a beam that rotates about its center, and two rotating wheels at each beam end around which the sutures are looped. The system provides for even distribution of force at the four attachment points on each side of the sample. Also, the point suture attachments allow each side of the gel to deform freely without resisting transverse shear stress [25]. In the case of the un-crosslinked gels, the gel holes were reinforced prior to suturing by quickly dabbing them with 25% glutaraldehyde followed by repeated washing with PBS. Both Schiff’s (Sigma) staining of the gel for glutaraldehyde, as well as heating to dissolve uncrosslinked parts of the gel, showed that the glutaraldehyde reinforcement did not spread more than 1.5 mm from the hole. Also, free lateral separation of the suture holes did not appear affected during the biaxial loading of the uncrosslinked gels.

Each gel was pre-loaded to an equi-biaxial load of 0.2gm, and then loaded according to a pre-determined loading ratio to a maximum of 15gm in any direction, for 10 cycles (200 sec/cycle). The data from the last loading cycle was used for data analysis. The following loading ratios (ratio of load in the two directions) were used - 1:3, 1:2, 2:3, 1:1, 3:2, 2:1 and 3:1. The gel strain during loading was calculated by tracking the displacement of the embedded polyethylene markers. After mechanical testing, the gel thickness was measured with a digital micrometer, and the average thickness was estimated to be 2.9 ± 0.3 mm.

Analysis of biaxial loading data

Throughout the document, the gel configuration after incubation in glutaraldehyde and prior to any loading will be called the ‘unloaded state’. The gel configuration at equi-biaxial preload force in the 10th loading cycle will be referred to as the ‘pre-loaded state’. The gel configuration at the maximal load in the 10th loading cycle will be referred to as the ‘loaded state’ for the particular loading ratio. All strains are reported as Lagrangian Green strains. Two reference states are used – the unloaded state and the pre-loaded state. Strains with respect to the unloaded state are denoted as ‘E’ and those with respect to the preloaded state by ‘EP’. In reporting the biaxial load forces and gel strains for the anisotropic gels, the direction along the predominant fibril direction is always referred to as the ‘fiber direction’ and denoted by subscript ‘11’. The direction perpendicular to fiber direction is referred to as the ‘cross-fiber direction’ denoted by subscript ‘22’. Due to the anisotropy in fibril orientation, the collagen gels are stiffer in the ‘fiber direction’ than in the ‘cross-fiber direction’.

BIOCHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION

All biochemical analysis was performed on the collagen gels after mechanical testing.

Shrinkage Temperature

The shrinkage temperature of glutaraldehyde-fixed collagenous tissue increases with crosslinking [26, 27]. Increased temperature disrupts the weak hydrogen bonding that holds the collagen triple helix together, and denatures it to random coils [28]. When external crosslinks reinforce the hydrogen bonding, the denaturation temperature of the tissue is increased. In glutaraldehyde-crosslinked tissues, denaturation appears as a shrinking of the tissue. This is because glutaraldehyde crosslinks are chemical crosslinks and are not disrupted by temperature. Consequently, when the collagen helices start to be denatured by temperature and the tissue starts to compact, the glutaraldehyde crosslinks remain intact and preserve the overall shape of the compacting tissue.

We determined the shrinkage temperature of collagen gels as an estimate of their glutaraldehyde crosslinking. After mechanical testing, the collagen gels were placed in a water bath, and heated at an approximate rate of 1°C/min. The temperature at which the gel size reduced to less than 50% of the original size was noted as the shrinkage temperature. Uncrosslinked gels did not shrink but dissolved at 53 °C.

Screening crosslinking conditions with shrinkage temperature assay

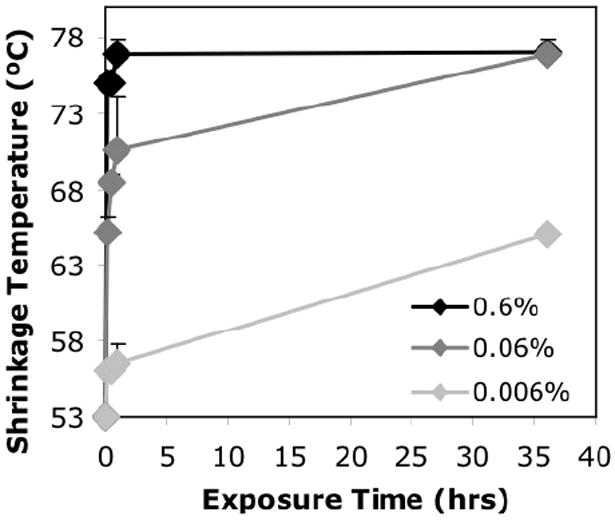

We did an initial screening assay to determine the conditions for incremental crosslinking to be used in the study. Collagen gels were exposed to crosslinking solutions of different glutaraldehyde concentrations (0.6%, 0.06%, 0.006% w/v), and for different exposure times (15min, 30min, 1hr and 36hr). Fig.2 shows the shrinkage temperature for the different conditions. There was a well-defined increase in shrinkage temperature for the three different concentrations at 1hr exposure time. There was also a well-defined increase in shrinkage temperature for the different exposure times at 0.06% glutaraldehyde concentration. Therefore we limited our subsequent study to the different glutaraldehyde concentrations at 1hr exposure time, and the different exposure times at 0.06% concentration.

Fig.2. Screening of crosslinking conditions.

Shrinkage temperature vs. exposure time for collagen gels crosslinked at different glutaraldehyde concentrations. Shrinkage temperature is a measure of the extent of crosslinking.

Gradient Elution on Reversed Phase HPLC

The amount of glutaraldehyde consumed in the crosslinking solution was measured by gradient elution on reversed phase HPLC (Hewlett-Packard 1090 HPLC with C18 Perkin-Elmer column). Glutaraldehyde monomers absorb at 280nm, and the absorbance is a linear function of monomer concentration [29, 30]. After fixation, a typical crosslinking supernatant contains unconsumed glutaraldehyde monomers, gel media, materials dissolved from the collagen gel, and any polymers formed by oxidation of the glutaraldehyde monomers. By eluting on a reversed phase HPLC on a gradient between acetonitrile and phosphate buffers (protocol based on Tashimi et. al [31]), monomeric glutaraldehyde was separated from the rest of the supernatant material as a 280nm elution peak. From the area of the elution peak, and by comparing against a calibration run, the concentration of glutaraldehyde monomers in the crosslinking solution was determined. A 235nm elution peak corresponding to glutaraldehyde polymers [29] was not detected, suggesting that there was no significant polymerization of glutaraldehyde monomers in the crosslinking solution. We report the molar glutaraldehyde consumption based on a glutaraldehyde MW of 100.12 [22].

TNBS assay

The TNBS (2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid) assay was used to estimate the amount of un-modified (hydroxy) lysine residues after gel fixation. TNBS derivatizes the primary form of the (hydroxy) lysine amines, and the resulting orange-colored product can be detected colorimetrically at 345nm. The primary lysine form is lost, however, when the lysine is involved in a glutaraldehyde-based crosslink. We followed the TNBS assay protocol described in [32]. Briefly, 1.4 – 1.6 mg of lyophilized gel was suspended in 1.0 ml of 4% (w/v) NaHCO3 and 1.0 ml of freshly prepared 0.5%(w/v) TNBS (Sigma). The mixture was heated to 40° C to derivatize unmodified lysine. The derivatization reaction was stopped after 2 hours by adding 3ml of 6N HCl. The mixture was then heated to 60° C for 90 minutes to hydrolyze collagen and release the amino acids into solution. The resulting amino acid solution was diluted with 5ml water, cooled to room temperature, and the concentration of the lysine derivative, trinitro-phenyl-lysine, was estimated from absorbance readings at 345 nm. Concentrations were calculated based on a molar absorptivity of 14600 l mol-1 cm-1 [32, 33]. We report the amount of lysine consumed in crosslinking as a percentage of the initial lysine content of the gel. Assuming each collagen alpha chain to have 30 (hydroxy) lysine residues (Allergan Inamed), the initial lysine content was estimated at 6.12 μM of (hydroxyl) lysine per collagen gel.

CNBr digestion

Cyanogen Bromide cleaves collagen at the methionine amino acid (5 – 9 methionines present per triple helix) into soluble peptide fragments. Upon crosslinking, a fraction of the peptides remain complexed and insoluble, and the amount of soluble collagen measured by hydroxyproline assay is decreased. The percentage of insoluble collagen is reported as an estimate of crosslinking. For the digestion, collagen gels were lyophilized, and dissolved in 70% deoxygenated formic acid at concentrations of 5-10mg/ml. 10%CNBr in formic acid was added to obtain a final concentration of 15mg CNBr/10mg collagen. The digestion mixture was then incubated at 30°C for 4 hours. Following digestion, the insoluble digestion products were precipitated by centrifugation, and 25ul and 50ul aliquots of supernatant were removed for hydroxyproline assay.

Collagenase digestion

Bacterial collagenase cleaves collagen within the triple helix molecule into several small peptide fragments. Upon crosslinking, a fraction of the protein remains insoluble, and is reported as an estimate of crosslinking extent. The collagenase digestion was performed as follows. 750 μl of 0.1% collagenase (high purity, Type VII, from Clostridium histolyticum, Sigma Aldrich Co.) in Sodium Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 1mM CaCl2 was added to 1.3-1.7 mg of lyophilized collagen. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. The insoluble digestion products were separated by centrifugation, and 25ul/50ul aliquots of the supernatant were removed for estimation of collagen concentration by hydroxyproline assay.

Hydroxyproline assay to estimate collagen concentration

The amino acid hydroxyproline is common in collagen but not in other proteins. Therefore the amount of hydroxyproline released by a collagenous material following acid hydrolysis can be used to estimate its collagen content. The Type 1 collagen in our study was approximately 10% hydroxyproline (personal communication, Allergan Inamed). The standardized protocol of Stegeman and Stadler [34] was used to measure the hydroxyproline content of the solubilized collagen.

SIMULATION ANALYSIS

At the micro-structural level, the cell-compacted collagen gel appears as an interconnected fibril system, with fibrils predominantly oriented perpendicular to the direction of compaction. We describe the axial stress-strain behavior of the collagen fibrils in the cell-compacted collagen gel as.

| eq.1 |

In the above equation, f is the axial fibril force, εf is the axial fibril strain, and A and B are parameters controlling the magnitude and non-linearity of the force response. The exponential function captures the slack in the rest state of the collagen fibers in cell-compacted collagen gels as well as the nonlinear behavior of uncrimped/straight collagen fibers themselves [35, 36][37].

A network model of fibril kinematics was used to describe fibril deformation in collagen gels [38, 39]. In an earlier study we showed that the network model captured the structure-mechanics relation in a collagen gel, particularly the high preload strains, to a better degree than affine models [13]. In a network model of fibril kinematics, the fibril interconnections constrain the deformation of the fibrils; i.e. for a given boundary strain, fibrils deform to balance forces at their interconnections. Fibril strain is obtained by simultaneously solving the nonlinear force-balance equations at the interconnections or nodes [38, 39].

| eq.2 |

where the summation is over the fibrils n intersecting at the qth node. Fibril nodes intersecting the boundary are assumed to move affine with the boundary. The average network stress (σij) is calculated from the fibril forces at the boundary, [40].

| eq.3 |

where the summation is over all boundary fibril nodes, and a is the area of the network. Resistance to fibril rotation was included as a resistance to the angle change between adjacent fibrils at an interconnection [39],

| eq.4 |

where R is the rotational stiffness, and fAOB is the rotational force due to the change in angle θAOB between neighboring fibrils at node O.

The input fibril distribution for the network mesh was obtained by affinely transforming a random mesh with the average deformation gradient of the collagen gel after cell compaction. In other words, the fibril distribution in a collagen gel is assumed to change affine with the overall gel strain during cell-compaction [14].

The value of A (Eq.1) was increased when simulating crosslinking as increased fibril stiffness. The value of R (Eq.4) was increased when simulating crosslinking as increased rotational stiffness.

RESULTS

Mechanical Analysis

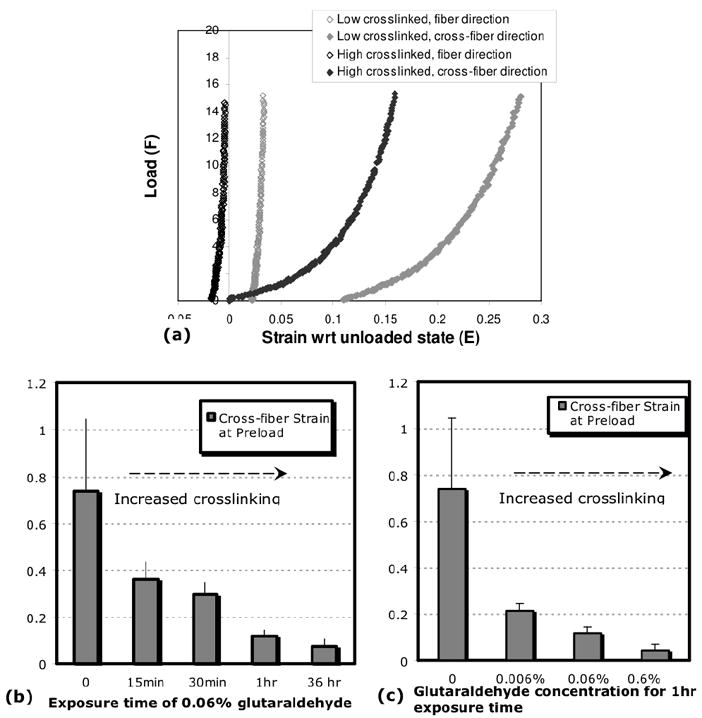

Crosslinking significantly decreased cross-fiber preloading strain

Figure 3a shows the load vs. strain curve for equibiaxial loading to 15gm, with the unloaded state as the Lagrangian strain reference. The curves are shown for a sample case of a low crosslinked gel (0.006% 15 min) and a sample case of a high crosslinked gel (0.06% 36 hrs). The low crosslinked gel showed large strains in the cross-fiber direction to reach the 0.2g preload. The cross-fiber strain to preload was much lower in the high crosslinked gel. Figures 3b and 3c show that an increase in crosslinking produced a steady decrease in the cross-fiber strain to preload (p<0.005, ANOVA).

Fig.3. Glutaraldehyde crosslinking and cross-fiber strain to preload.

(a) Equi-biaxial loading to 15g for case of low-crosslinked and high-crosslinked gel, with strains referenced to unloaded state of gel. The conditions for low and high crosslinking are 1hr exposure to 0.006% glutaraldehyde, and 36 hours exposure to 0.06% glutaraldehyde, respectively. The high-crosslinked gel (black) shows decreased cross-fiber strains (EP22) to the low force preload of 0.2gm, compared to the low-crosslinked one (grey). (b,c) Trends in the cross-fiber preload strain with increased crosslinking. Crosslinking was increased by either increasing the exposure time at constant glutaraldehyde concentration of 0.06% w/v (b) or by increasing the glutaraldehyde concentration at constant exposure time of 1 hour (c). In both cases, cross-fiber strains to preload decreased progressively with increasing crosslinking. The trend suggests that crosslinking decreased the cross-fiber gel compliance at low forces.

In Fig. 4a we show the load-strain curves for equibiaxial loading to 15gm, with the preloaded state as the Lagrangian strain reference. The low and high crosslink conditions are similar to above. The cross-fiber strain to the maximal 15g loading can be considered a gross index of gel compliance. Figure 4a suggests that the high crosslinked gel is more compliant than the low crosslinked gel. Figures 4b and 4c show the average cross-fiber strains from preload for the different crosslinking conditions. While the plots suggest that the cross-fiber strain from preload increases with crosslinking, the trend is not statistically significant (p>0.05, ANOVA).

Fig.4. Glutaraldehyde crosslinking and cross-fiber strain.

(a) Equi-biaxial loading to 15g shown for low-crosslinked and high-crosslinked gels, with the strains referenced to preloaded state (Ep). The conditions for low and high crosslinking are 1hr exposure to 0.006% glutaraldehyde, and 36 hours exposure to 0.06% glutaraldehyde, respectively. The cross-fiber strain (EP22) at 15 gm is greater for the high crosslinked gel. (b,c) Trends in cross-fiber strain (EP22) with increased crosslinking. Crosslinking was increased by increasing exposure time at a constant glutaraldehyde concentration of 0.06% w/v (b), or by increasing glutaraldehyde concentration at a constant exposure time of 1 hour (c). While the trends suggest that the cross-fiber strain increases with crosslinking, they are not statistically significant (see text).

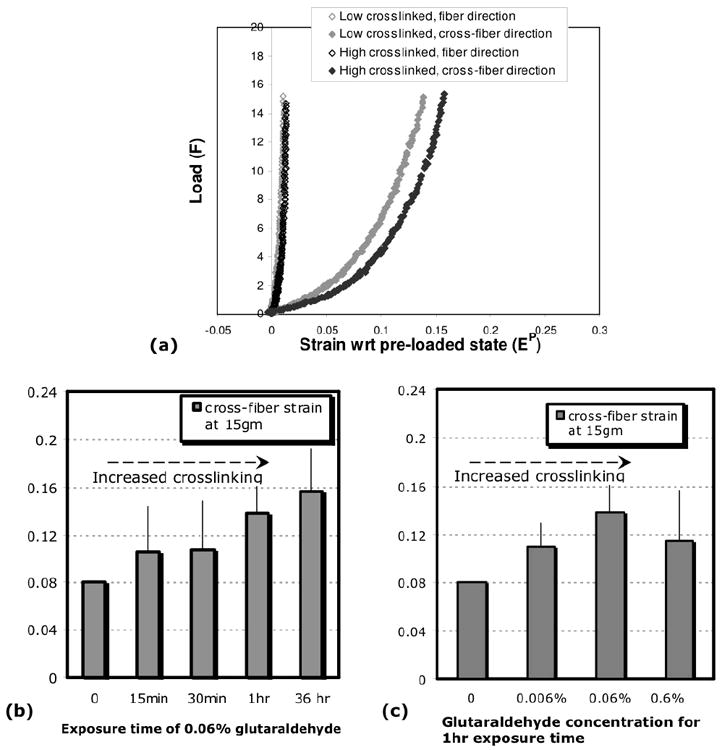

Crosslinking significantly decreased coupling between the biaxial load and strain anisotropy

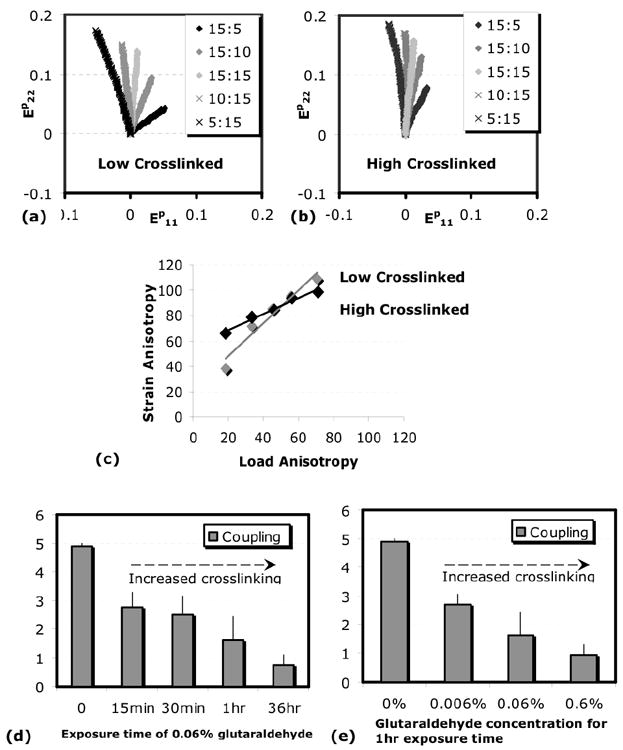

Figures 5a and 5b show the biaxial strain trajectories (EP22 vs. EP11) for a low crosslinked gel (0.06% 10min) and a high crosslinked gel (0.06% 36hrs) subjected to several loading protocols. For the same set of biaxial loading protocols, the low crosslinked gel showed a larger splay or spread of the biaxial strain curves than the high crosslinked gel (Fig. 5a,b). The spread of the biaxial strain curves is a measure of the coupling between the strain anisotropy and load anisotropy, i.e. the change in strain anisotropy produced by a change in the load anisotropy. The low crosslinked gel shows a larger load-strain coupling than the high crosslinked gel.

Fig.5. Glutaraldehyde crosslinking and strain-load coupling.

(a,b) Biaxial strains (EP22 vs EP11) for the different loading protocols (legend) shown for the case of low crosslinked gel (a) and high crosslinked gel (b). The spread of the biaxial curves, which indicates the coupling between the biaxial strain and load anisotropy, is smaller for the high crosslink case. (c) The coupling was quantified as the slope of the biaxial strain vs. biaxial load anisotropy. (d,e) The coupling between the strain and load anisotropy decreased progressively with increased crosslinking.

To quantify the coupling between the load and strain anisotropy, we defined load and strain angles (θE and θF) from the loads and strains at the end of a biaxial loading curve:

| eq.5 |

| eq.6 |

We then plotted the strain angle against the load angle, taking the slope of the resulting plot as a measure of coupling (Fig.5c). Figures 5d and e show the average values of coupling for the different crosslink conditions. A decrease in coupling occurs as crosslinking increases from increased time of exposure or from increased glutaraldehyde concentration.

Biochemical Analysis

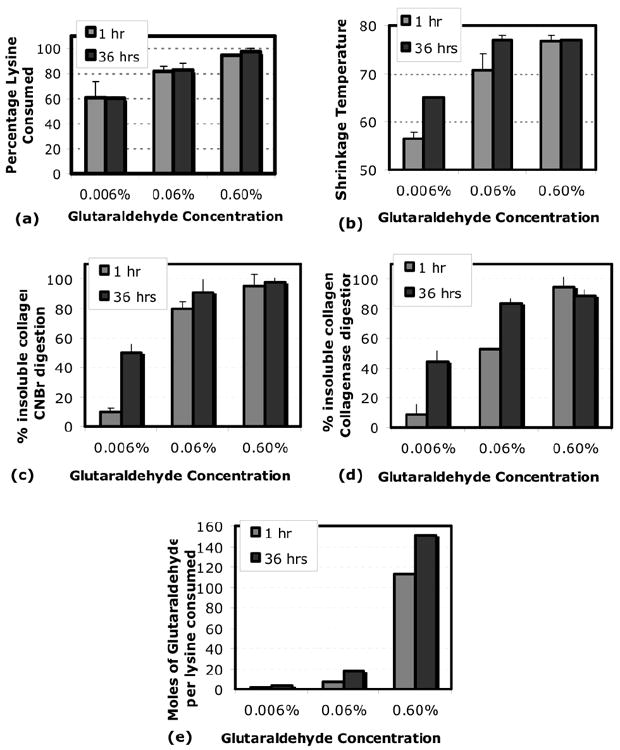

Four biochemical measures were determined to identify the structural changes in the collagen gels with crosslinking. The four were: resistance to collagenase digestion, resistance to CNBr digestion, percentage lysine consumed, and shrinkage temperature. All four measures increased with crosslinking. However, two different trends arose when the biochemical data at 1 and 36 hours were compared for all three glutaraldehyde concentrations (Fig.6a-d). Lysine consumption depended on glutaraldehyde concentration only (Fig.6a), whereas the shrinkage temperature increased with both glutaraldehyde concentration and time of exposure (Fig.6b). The resistance to collagenase digestion (Fig.6c) and CNBr digestion (Fig.6d) showed trends similar to the shrinkage temperature.

Fig.6. Biochemical analysis of collagen gels crosslinked with glutaraldehyde concentrations of 0.006%, 0.06%, and 0.6%, for exposure times of 1 and 36 hours.

(a) Lysine consumption, (b) Gel shrinkage temperature, (c) moles of glutaraldehyde per mole of lysine consumed, (d) % resistance to CNBr digestion, (e) % resistance to collagenase digestion. The lysine consumption, a measure of the number of crosslinked lysines, increased with glutaraldehyde concentration only. The shrinkage temperature, a measure of collagen crosslinks and glutaraldehyde polymerization, increased with both glutaraldehyde concentration and exposure time. The biochemical data in (c),(d), and (e) showed trends similar to the shrinkage temperature.

The above behavior of the shrinkage temperature is consistent with studies that show it increases with both lysine crosslinking and increased matrix complexity from glutaraldehyde polymerization [22]. Glutaraldehyde polymerization occurs at large exposure times and large monomer concentrations [22]. Gels crosslinked at higher exposure times and monomer concentrations have more than ten glutaraldehyde monomers per mole of lysine (Fig.6e), suggesting the presence of glutaraldehyde polymers in these gels. Moreover, collagen gels with high shrinkage temperature showed a yellowish hue, which is associated with the presence of glutaraldehyde polymers [22].

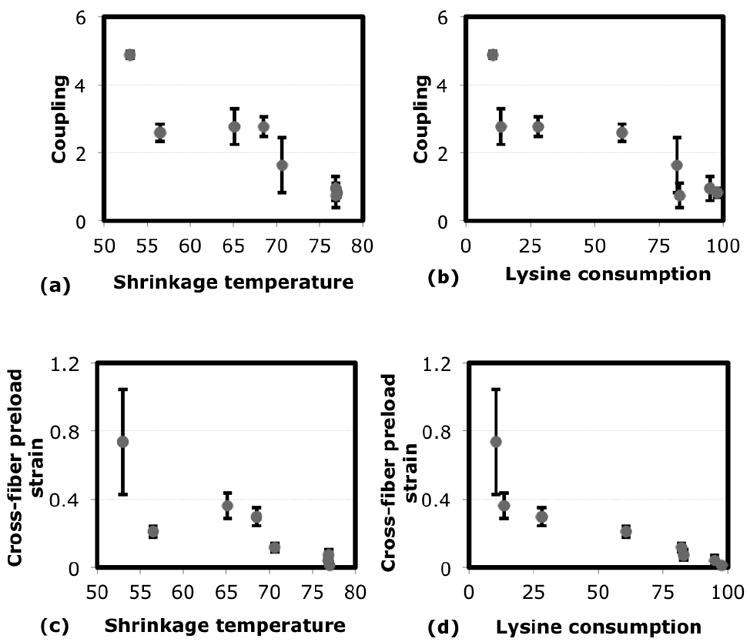

The biochemical observations suggest that there are two ways that glutaraldehyde crosslinking might alter gel microstructure. One is by crosslinking lysine groups within collagen fibrils. The second is by forming polymer networks that extend the crosslinking to between fibrils, and that might by itself contribute to the gel mechanics. The former is estimated by the lysine consumption data, and the latter by the shrinkage temperature data. To understand which of these crosslinking scenarios primarily determined the mechanical trends, we plotted the average mechanical data against the corresponding lysine consumption and shrinkage temperature data (Fig7). Figures. 7a,b show that the average coupling in general decreases with both biochemical parameters. No localized departure from the general trend can be interpreted because of the large standard deviations in the data. On the other hand, the standard deviations in the average preload data are relatively small. While it decreases in general with both shrinkage temperature and lysine consumption (Figs.7c,d), there is a significant departure from the trend between shrinkage temperatures 56°C to 65°C. The average preload decreases as shrinkage temperature increases from 56°C to 65°C, and then increases again (p < 0.01 by Student T test). No such localized deviations are seen, however, when the average preload is plotted against the lysine consumption. It decreases steadily throughout with increase in lysine consumption (p < 0.01 by ANOVA). (Fig.7d). The consistency of the relation between the lysine consumption and mechanical data suggests that lysine consumption is a better predictor of the mechanical changes, and therefore crosslinking within fibrils is the likely cause of the mechanical trends.

Fig.7. Relation between mechanical and biochemical trends.

(a,b) Average strain-load coupling plotted against shrinkage temperature (a) and lysine consumption (b) for different crosslinking conditions. The average coupling generally decreases with both, and no localized deviations from the trend are visible due to the large standard deviations.

(c,d) The average cross-fiber strain to preload (EP22) plotted against shrinkage temperature (c) and lysine consumption (d) for different crosslinking conditions. In the plot against shrinkage temperature (c), there is a significant deviation from the general trends between 56°C and 65°C. The relation with lysine consumption is more consistent (d).

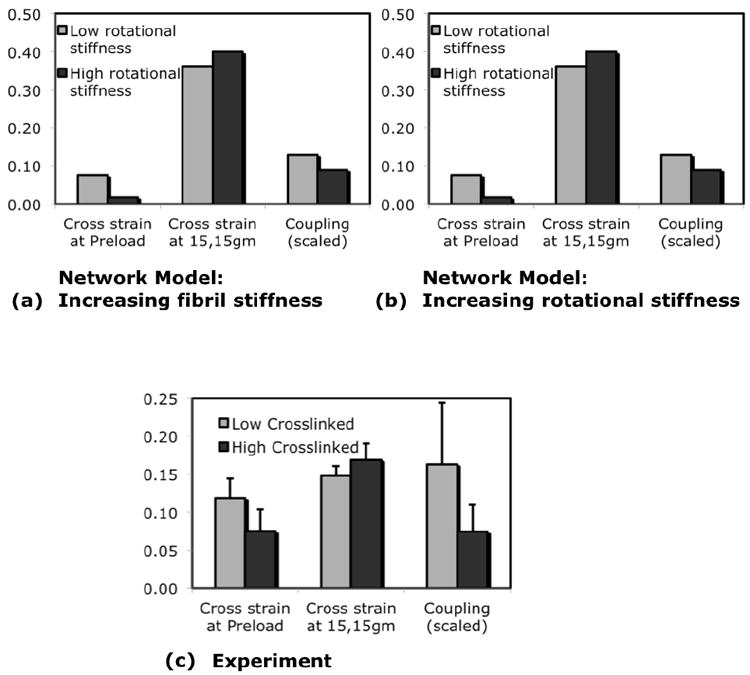

Simulation analysis

Crosslinking within fibrils could alter gel mechanics by either increasing the resistance to fibril extension (increased fibril stiffness) or increasing the resistance to fibril rotation. These two microstructural mechanisms were implemented in a network model of collagen gel mechanics, which was then subjected to the different biaxial loading protocols. Figure 8 shows the simulation predictions for the mechanical trends resulting from increased fibril stiffness and increased rotational stiffness, compared against experimental observations. Only increasing fibril rotationaI stiffness produced the mechanical trends observed in experiments. There was a decrease in preload strain and coupling, and also an increase in the cross-fiber deformation from preload. Increasing fibril axial stiffness reproduced the decrease in preload strain, but could not reproduce the trends in coupling and cross-fiber deformation from preload. The mechanical trends seen in simulations were not dependent on the choice of parameters in the governing equations (Eqs.1,4).

Fig.8. Model predictions for effects of two microstructural mechanisms on cross-fiber strain.

Increasing fibril stiffness (a) reduced cross-fiber strain at 15g relative to preload and slightly increased coupling. Increasing rotational stiffness (b) reduced cross-fiber strain at preload, slightly increased cross-fiber strain at 15g relative to preload, and decreased coupling. Experimental data (c) for 0.06% glutaraldehyde treatment for 1 hour (low crosslinking) and 36 hours (high crosslinking) showed the same trends as increasing rotational stiffness in the model but did not match model results for increased axial stiffness.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to determine the micro-structural basis for the mechanical changes in collagen gels that are crosslinked with glutaraldehyde. The following methodology was used: anisotropic collagen gels were crosslinked with glutaraldehyde to different extents; trends in their mechanical and biochemical properties with increased crosslinking were observed; and the microstructural mechanism that produced similar trends in a network model of filament kinematics was identified. Below we discuss our results and other comparable observations in literature.

Mechanical analysis

Under uniaxial and biaxial loading, collagen gels and soft tissues typically show large compliance at low forces followed by a non-linear stiffening [14, 41-43]. We observed that glutaraldeyde crosslinking of collagen gels decreased the compliance at low forces (or the preload strain), particularly in the cross-fiber direction, with a trend towards increased compliance at high forces that was not significant at our sample size.

Several studies have reported similar mechanical changes following crosslinking [43-45]. Tower et al [41] observed a decrease in the low-force extensibility of glutaraldehyde-fixed, anisotropic collagen gels. Zioupos et al [44] reported a decrease in low-force strains in fixed anisotropic pericardial tissue, with no significant change in the ultimate tensile strength and the terminal elastic modulus. Billiar et al [46] reported that glutaraldehyde-treated valve cusps appeared more compliant than untreated cusps, when the biaxial strains where referenced to a preload strain [46]. Zioupos et al [44] noted that when the uniaxial extension strains of an anisotropic pericardial strip were referenced to the preconditioned strain at 0.8MPa, the crosslinked tissue appeared more compliant than the fresh tissue in the cross-fiber direction. Damink et al [17] observed that dermal sheep collagen showed an increase in the low-strain modulus and a decrease in the high-strain modulus after crosslinking. The increased compliance exhibited by crosslinked samples at strains beyond preload or when the strain is reference to the preload strain can be rationalized as follows: Most of the strains in the low crosslinked samples occur in the low-force ‘toe’ region, whereas most of the strains in the high crosslinked samples occur in the non-linear high-force region. Therefore, when the pre-load state is taken as strain reference, the low crosslinked sample appears stiffer because a significant part of its strain capacity is extinguished before preload is reached.

Biaxial mechanical testing also allowed us to examine changes in coupling between the primary fiber and cross-fiber directions in these anisotropic model tissues. The term coupling refers to the fact that stretch along one axis affects stresses not only in that direction but also in perpendicular directions. Often this coupling is modeled with Fung-type strain energy functions that give rise to expressions for normal stress components that depend on multiple strain components, e.g. Sff = f (Eff, Ecc) where Sff is the second Piola-Kirchoff normal stress component in the fiber direction and depends on strain components in both the fiber and cross-fiber directions. In our load-controlled tests, the spread in strain paths during loading to identical loads provided a measure of coupling. For example, with maximal load ratios of 15:5g and a higher level of coupling (Figure 5a), stretch induced in the fiber direction by the 15g load also balanced most of the load applied in the cross-fiber direction, so the cross-fiber loading induced little cross-fiber stretch. When crosslinking reduced coupling (Fig. 5b), the same loads induced much more deformation in the cross-fiber direction. Previous studies of valve leaflet crosslinking have reported that the coupling between the two biaxial testing axes decreases with crosslinking [42, 47, 48].

Biochemical analysis

Glutaraldehyde (GA) is a linear, 5-carbon di-aldehyde [49] and is among the strongest known crosslinking agents [32, 45]. It is widely used for tanning in the leather industry, as a fixative agent for electron microscopy, and for reducing the antigenicity and thrombogenicity of bio-prosthetic tissues [22]. It reacts with the primary amine groups of (hydroxyl)-lysine residues in collagen to form intermediate Schiff’s bases, which then convert to stable and complex crosslinks [50, 51]. Glutaraldehyde is an effective crosslinker because it forms stable lysine crosslinks, and because it polymerizes and crosslinks lysine residues larger distances apart [22]. Typically 6-8 molecules of glutaraldehyde are involved in one lysine-lysine crosslink [50, 52, 53]. However at high concentrations and temperature, glutaraldehyde polymerizes to form extensive networks which increase the shrinkage temperature of the matrix [22] and its resistance to collagenase digestion [54, 55]. Lysine consumption data quantifies the glutaraldehyde crosslinking within fibrils. Shrinkage temperature data captures the crosslinking within fibrils and that between fibrils by glutaraldehyde polymers. When the average mechanical data was plotted against both, we found that the shrinkage temperature did not consistently predict the mechanical changes of increased crosslinking. This suggested that the lysine consumption, and therefore crosslinking within fibrils, was more likely responsible for the gel-scale mechanical trends.

Simulation analysis

Lysine crosslinking within fibrils can change the gel micromechanics is two ways: (1) increasing the axial stiffness of a collagen fibril, and (2) increasing its resistance to rotation (by crosslinking at the fiber interconnections or by increasing the fiber bending stiffness). To determine which of these was responsible for the gel-scale mechanical trends, we implemented them separately in a network model of collagen gels and simulated the biaxial loading of increasingly ‘crosslinked’ gels. Network [38, 39] and affine [13, 14] models have been used to study collagen gel mechanics. The former is a uniform stress model, whereas the latter is a uniform strain model. We used the network model because it produces fibril rearrangements similar to experiments [39], and because it does better at predicting the anisotropic mechanics of collagen gels using fibril parameters obtained from isotropic gel mechanics [13]. Representing crosslinking as increased rotational resistance in the network model reproduced all the mechanical trends observed in the biaxial experiments. A decrease in load-strain coupling was not observed in the model when crosslinking was represented as increased fibril stiffness

Our analyses suggest that the mechanical changes in crosslinked gels likely resulted from the increased rotational resistance of the crosslinked fibrils. The conclusion is supported by birefringence experiments in which uncrosslinked gels show extensive fibril rotation during preload, but glutaraldehyde-fixed gels do not [56]. The network model suggests that fibril rotation is the primary microstructural mode by which overall gel strain is accommodated, particularly at small strains [38]. Since fibril rotation appears to be a dominant deformation mode in collagen gels, it is not surprising that the mechanical effects of crosslinking are caused by an increased resistance to fibril rotation.

Limitations and sources of error

We used collagen gels as a model system for these studies. The important advantage of collagen gels for this study was that they contain only collagen fibers, without other matrix components, allowing us to focus on the effects of crosslinking on a collagen fiber network. However, the absence of other matrix components also means that the mechanics and fiber kinematics of collagen gels differ from those of more complex biologic tissues, suggesting caution in extrapolating the results of this study. To our knowledge, there has been one observation that glutaraldehyde-fixed bioprosthetic aortic valves display decreased shear deformability [57], suggesting that the increased resistance to fibril rotation might be a factor in crosslinked tissues. In another study, Billiar et al [43] used an affine fiber model to identify the microstructural mechanism behind the mechanical changes in glutaraldehyde-crosslinked aortic valve cusps [42]. The mechanical changes, however, were attributed to increased fibril stiffness and reduced anisotropy of the fibril orientation distribution.

Another limitation of this study was that we did not attempt to fit precisely the microstructure or mechanics of individual gels or groups of gels; for example, in Figure 8 the model over-predicts strains at 15g of load by a factor of 2. Because we found that trends in mechanical behavior in the model (increases or decreases in strain and coupling) were independent of the exact choice of model parameters, and that only one of the two microstructural mechanisms consistent with the biochemical data could reproduce the mechanical trends we observed experimentally, we felt that fitting the model precisely to the mechanical data from the various experimental groups would not provide additional insight into the underlying microstructural mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

We used a combined mechanical, biochemical and simulation approach to identify the microstructural mechanism by which glutaraldehyde crosslinking alters mechanical properties of anisotropic collagen gels. Increased crosslinking decreased the cross-fiber strain to a small equibiaxial preload, and decreased coupling between the fiber and cross-fiber direction. It also tended to decrease the cross-fiber strain referenced to the preload strain, These mechanical trends were better described by changes in lysine consumption than by changes in gel shrinkage temperature. Simulations showed that, of the two microstructural mechanisms related to increased lysine consumption, the mechanical trends were reproduced only when crosslinking was represented as increased resistance to fibril rotation. We conclude that the microstructural mechanism underlying the mechanical changes observed in glutaraldehyde-crosslinked collagen gels is an increased resistance to the rotation of fibrils relative to each other.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 HL075639 (JWH). The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Michael Sacks for sharing the design of his custom biaxial stretcher and Drs. Kevin Costa, Gregory Fomovsky, and Eun-Jung Lee for input regarding the design and interpretation of the studies.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Brinckmann J, Notbohm H, Müller PK, editors. Collagen - primer in structure, processing and assembly. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenzel KH, Miyata T, Rubin AL. Collagen as a biomaterial. Annual Review of Biophysics and Bioengineering. 1974;3(1):231–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.03.060174.001311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadler KE, Holmes DF, Trotter JA, Chapman JA. Collagen fibril formation. Biochem J. 1996 May 15;316(1):1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj3160001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyre DR, Paz MA, Gallop PM. Cross-Linking in Collagen and Elastin. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1984;53(1):717–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormick RJ, Thomas DP. Collagen crosslinking in the heart: relationship to development and function. Basic Appl Myol. 1998;8(2):143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey AJ, Light ND, Atkins EDT. Chemical cross-linking restrictions on models for the molecular organization of the collagen fibre. Nature. 1980;288(5789):408–10. doi: 10.1038/288408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eyre DR, Dickson IR, Van Ness K. Collagen cross-linking in human bone and articular cartilage. Age-related changes in the content of mature hydroxypyridinium residues. Biochem J. 1988 Jun 1;252(2):495–500. doi: 10.1042/bj2520495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnard K, Light ND, Sims TJ, Bailey AJ. Chemistry of the collagen cross-links. Origin and partial characterization of a putative mature cross-link of collagen. Biochem J. 1987 Jun 1;244(2):303–0. doi: 10.1042/bj2440303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes JW, Borg TK, Covell JW. Structure and mechanics of healing myocardial infarcts. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2005;7(1):223–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goissis G, Yoshioka SA, Braile DM, Ramirez VDA. The chemical protecting group concept applied in crosslinking of natural tissues with glutaraldehyde acetals. Artificial Organs. 1998;22(3):210–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.1998.06006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naimark WA, Pereira CA, Tsang K, Lee JM. HMDC crosslinking of bovine pericardial tissue: a potential role of the solvent environment in the design of bioprosthetic materials. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 1995;6(4):235–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zilla P, Bezuidenhout D, Weissenstein C, Walt A, Human P. Diamine extension of glutaraldehyde crosslinks mitigates bioprosthetic aortic wall calcification in the sheep model. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2001;56(1):56–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200107)56:1<56::aid-jbm1068>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomopoulos S, Fomovsky GM, Chandran PL, Holmes JW. Collagen fiber alignment does not explain mechanical anisotropy in fibroblast populated collagen gels. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129(5):642. doi: 10.1115/1.2768104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomopoulos S, Fomovsky GM, Holmes JW. The development of structural and mechanical anisotropy in fibroblast populated collagen gels. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127(5):742–50. doi: 10.1115/1.1992525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell E, Ivarsson B, Merrill C. Production of a tissue-like structure by contraction of collagen lattices by human fibroblasts of different proliferative potential in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1979;76:1274–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandran PL, Barocas VH. Microstructural mechanics of collagen gels in confined compression: poroelasticity, viscoelasticity, and collapse. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2004 Apr;126(2):152–66. doi: 10.1115/1.1688774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olde Damink LHH, Dijkstra PJ, Van Luyn MJA, Van Wachem PB, Nieuwenhuis P, Feijen J. Glutaraldehyde as a crosslinking agent for collagen-based biomaterials. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 1995;6(8):460–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopwood D. Theoretical and practical aspects of glutaraldehyde fixation. The Histochemical Journal. 1972;4(4):1573–6865. doi: 10.1007/BF01005005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopwood D. Some aspects of fixation with glutaraldehyde. A biochemical and histochemical comparison of the effects of formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde fixation on various enzymes and glycogen, with a note on penetration of glutaraldehyde into liver. J Anat. 1967;10(1):83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knezevic V, Sim AJ, Borg TK, Holmes JW. Isotonic biaxial loading of fibroblast-populated collagen gels: a versatile, low-cost system for the study of mechanobiology. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2002;1:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s10237-002-0005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grinnell F, Lamke CR. Reorganization of hydrated collagen lattices by human skin fibroblasts. Journal of Cell Science. 1984;66:51–63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.66.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayat M. Glutaraldehyde: role in electron microscopy. Micron and Microscopica Acta. 1986;17(22):115–35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacks MS, Sun W. Multiaxial mechanical behavior of biological materials. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;5(1):251–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacks MS. Biaxial mechanical evaluation of planar biological materials. Journal of Elasticity. 2000;61:199–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waldman SD, Sacks MS, Lee JM. Boundary conditions during biaxial testing of planar connective tissues Part II Fiber orientation. Journal of Materials Science Letters. 2002;21(15):1215–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1019896210320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore MA, Chen W, Phillips RE, Bohachevsky IK, McIlroy BK. Shrinkage temperature versus protein extraction as a measure of stabilization of photooxidized tissue. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1996;32(2):209–14. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199610)32:2<209::AID-JBM9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simionescu A, Simionescu D, Deac R. Lysine-enhanced glutaraldehyde crosslinking of collagenous biomaterials. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1991;25(12):1495–505. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820251207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan AC, Boughner D, Vesely I. Viscoelasticity of dynamically fixed bioprosthetic valves. II. Effect of glutaraldehyde concentration. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997 Feb 1;113(2):302–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korn AH, Feairheller SH, Filachione EM. Glutaraldehyde: nature of the reagent. J Mol Biol. 1972;65(3):525–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson PJ. Purification and quantification of glutaraldehyde and its effect on several enzyme activities in skeletal muscle 652. J Histochem and Cytochem. 1967;15:652. doi: 10.1177/15.11.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashima T, Kawakami U, Satoh N, Nakagawa T, Tanaka H. Detection of Impurities in Aqueous Solution of Glutaraldehyde by High Performance Liquid Chromatography with a Multichannel Photodiode Array UV Detector. J Electron Microscopy. 1987 Jan 1;36(3):136–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lastowka A, Maffia G. A comparison of chemical, physical and enzymatic crosslinking of bovine type 1 collagen fibrils. Journal of American Leather Chemists Association. 2005;100:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarman-Smith ML, Bodamyali T, Stevens C, Howell JA, Horrocks M, Chaudhuri JB. Porcine collagen crosslinking, degradation and its capability for fibroblast adhesion and proliferation. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2004;15(8):925–32. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSM.0000036281.47596.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stegeman H, Stalder K. Determination of hydroxyproline. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;18:267–73. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung YC. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misof K, Rapp G, Fratzl P. A new molecular model for collagen elasticity based on synchrotron X-ray scattering evidence. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72(3):1376–81. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78783-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puxkandl R, Zizak I, Paris O, Keckes J, Tesch W, Bernstorff S, et al. Viscoelastic properties of collagen: synchrotron radiation investigations and structural model. 2002:191–7. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandran PL, Barocas VH. Affine versus non-affine fibril kinematics in collagen networks: theoretical studies of network behavior. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128(2):259–70. doi: 10.1115/1.2165699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandran PL, Barocas VH. Deterministic material-based averaging theory model of collagen gel micromechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129(2):137–47. doi: 10.1115/1.2472369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandran PL, Barocas VH. Affine vs. Non-Affine Fibril Kinematics in Collagen Networks: Theoretical Studies of Network Behavior. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2005 doi: 10.1115/1.2165699. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tower TT, N M, Tranquillo RT. Fiber alignment imaging during mechanical testing of soft tissues. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30(10):1221–33. doi: 10.1114/1.1527047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Billiar KL, Sacks MS. Biaxial mechanical properties of the natural and glutaraldehyde treated aortic valve cusp--Part I: Experimental results. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2000 Feb;122(1):23–30. doi: 10.1115/1.429624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Billiar KL, Sacks MS. Biaxial mechanical properties of the fresh and glutaraldehyde treated porcine aortic valve: Part II - A structurally guided constitutive model. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122(4):327–35. doi: 10.1115/1.1287158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zioupos P, B JC, F J. Anisotropic elasticity and strength of glutaraldehyde fixed bovine pericardium for use in pericardial bioprosthetic valves. J Biomed Mater Res. 1994;28(1):49–57. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820280107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Noort R, Yates SP, Martin TR, Barker AT, Black MM. A study of the effects of glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde on the mechanical behaviour of bovine pericardium. Biomaterials. 1982;3(1):21–6. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(82)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Billiar KL, Sacks MS. Biaxial mechanical properties of the fresh and glutaraldehyde treated porcine aortic valve: Part I - Experimental results. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:23–30. doi: 10.1115/1.429624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayne AS, Christie GW, Smaill BH, Hunter PJ, Barratt-Boyes BG. An assessment of the mechanical properties of leaflets from four second- generation porcine bioprostheses with biaxial testing techniques. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989 Jul 1;98(2):170–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sacks MS, Chuong CJ. Orthotropic mechanical properties of chemically treated bovine pericardium. Ann Biomed Eng. 1998;26(5):892–902. doi: 10.1114/1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Migneault I, Dartiguenave C, Bertrand MJ, Waldron KC. Glutaraldehyde: behavior in aqueous solution, reaction with proteins, and application to enzyme crosslinking. BioTechniques. 2004;37(5):790–802. doi: 10.2144/04375RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richards FM, Knowles JR. Glutaraldehyde as a protein crosslinking reagent. J Mol Biol. 1968;37:231–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wine Yariv, C-H N, F A, F F. Elucidation of the mechanism and end products of glutaraldehyde crosslinking reaction by X-ray structure analysis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2007;98(3):711–8. doi: 10.1002/bit.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowes JH, Cater CW. Cross-linking of collagen. J Appl Chem. 1965;15:296. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bowes JH, Cater CW. The interaction of aldehydes with collagen. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1968;168:341. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(68)90156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung DT, Nimni ME. Mechanism of crosslinking of proteins by glutaraldehyde II. Reaction with monomeric and polymeric collagen. Connect Tissue Res. 1982;10:201–16. doi: 10.3109/03008208209034419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chuji Aso, Y A. Studies on the polymerization of bifunctional monomers. II. Polymerization of glutaraldehyde. Die Makromolekulare Chemie. 1962;58(1):195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tower TT, Neidert MR, Tranquillo RT. Fiber alignment imaging during mechanical testing of soft tissues. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2002;30(10):1221–33. doi: 10.1114/1.1527047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duncan AC, Boughner D, Vesely I. Dynamic glutaraldehyde fixation of a porcine aortic valve xenograft. I. Effect of fixation conditions on the final tissue viscoelastic properties. Biomaterials. 1996;17(19):1849–56. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]