Abstract

Manganese (Mn) is essential for normal physiologic functioning; therefore, deficiencies and excess intake of manganese can result in disease. In humans, prolonged exposure to manganese causes neurotoxicity characterized by Parkinson-like symptoms. Mn2+ has been shown to mediate DNA damage possibly through the generation of reactive oxygen species. In a recent publication, we showed that Mn induced oxidative DNA damage and caused lesions in thymines. This study further investigates the mechanisms by which cells process Mn2+-mediated DNA damage using the yeast S. cerevisiae. The strains most sensitive to Mn2+ were those defective in base excision repair, glutathione synthesis, and superoxide dismutase mutants. Mn2+ caused a dose-dependent increase in the accumulation of mutations using the CAN1 and lys2-10A mutator assays. The spectrum of CAN1 mutants indicates that exposure to Mn results in accumulation of base substitutions and frameshift mutations. The sensitivity of cells to Mn2+ as well as its mutagenic effect was reduced by N-acetylcysteine, glutathione, and Mg2+. These data suggest that Mn2+ causes oxidative DNA damage that requires base excision repair for processing and that Mn interferes with polymerase fidelity. The status of base excision repair may provide a biomarker for the sensitivity of individuals to manganese.

1. Introduction

Manganese (Mn) is a trace element that has been extensively documented for its varied role in the body's homeostasis. As an essential nutrient, Mn is required for the normal function and development of the brain [1], metabolism of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates [2–4], and also as a functional unit for many enzymes [3–5]. Therefore, deficiencies that affect fetal development [6] and excess Mn (environmental exposure and/or elevated dietary Mn [7]), can result in disorders and disease.

There is increasing concern for the use of organic compounds containing manganese in industrial settings. In recent years, methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT) gained approval for use in the United States as an octane enhancing fuel additive used in unleaded automotive gasoline. Exposure to Mn has also increased through occupation and environmental settings. This includes agrochemicals such as the fungicides, maneb and mancozeb, and pesticides in the agriculture and forest industries [8] as well as in the case of miners, smelters, welders, and workers in battery factories [9]. The increase in atmospheric levels could result in potential health risks.

At elevated levels of exposure, Mn has been shown to cause manganism, which is an excess of manganese in the basal ganglia [10]. Manganism is characterized by neurological symptoms resembling the dystonic movement associated with Parkinson's disease (PD) [11–13] and therefore is a risk factor for idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD). Although Mn has been studied for years, the mechanism by which it causes neuronal damage is not well understood. Studies suggest that neurotoxicity is not caused by a single factor but that it appears to be regulated by a number of factors including apoptosis, oxidative injury, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation [14–18].

The mutagenicity of Mn has been extensively documented [19]. Mn has been shown to cause damage to DNA in multiple cell-based assays [18, 20], to interfere with the fidelity of DNA replication [21], to activate the DNA damage response [22], to induce mutations in T4 phage replication [23] and yeast mitochondria replication [24, 25], and, inhibit repair factor PARP in human cells [26], albeit not scoring as a direct mutagen in the Ames test [27]. Despite its mutagenicity, Mn is not classified as a carcinogen in humans. The reasons for this discrepancy are still not clear.

Research on manganese toxicity has increased in recent years. However, the mechanisms underlying its multiple toxicities (neurotoxicity, genotoxicity, mutagenicity, etc.) [19] remain a mystery. It is possible that redundant mechanisms of DNA repair exist which are effective to handle the levels of Mn to which cells are exposed.

The goal of the current study is to gain insight into the pathways that are involved in DNA damage/repair that contribute to protecting cells from the toxicity of manganese (Mn). The yeast S. cerevisiae was utilized as a model system to study the genotoxic effects of Mn. Yeast has proven to be an excellent eukaryotic model for studying metal, and players identified through genetic studies virtually all have homologues in humans. In our study, we use two well-established mutator assays. The CAN1 assay was used to measure the induction of forward mutations, and the lys2-10A reversion assay was used to assess replication fidelity. Furthermore, this study examines the protective effects of the antioxidants N-acetylcysteine and glutathione, as well as Mg2+ on Mn-induced toxicity and mutagenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Genetic Methods and Strains

Yeast extract/peptone/dextrose (YPD, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, 2% agar) and synthetic complete (SC, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acid, 0.087% amino acid mixture, 2% dextrose, 2% agar) media or the corresponding drop-out media were as described in [28, 29]. Homozygous haploid deletion strains library (Parental strain BY4741: MATa his3∆1 leu2∆0 met15∆0 ura3∆0) was obtained from Thermo Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

2.2. Chemicals

Manganese chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2-4H2O), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), glutathione (GSH), canavanine, and yeast media were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.3. Sensitivity of Strains to Mn2+ and Effect of NAC and GSH

The concentration of Mn2+ for strain exposure was determined experimentally using the wild type parental strain, BY4741. Briefly, single colonies were grown for 16 h on YPD with or without Mn2+ at 30°C with shaking. Cells were then washed with and resuspended in sterile water. Serial dilutions were spotted onto YPD and plates were incubated at 30°C. Cell growth was monitored daily and sensitivity was scored after 3 days. Colonies were counted and survival (in percentage) was calculated relative to the untreated control. Each strain was tested using at least five independent colonies for each Mn2+ concentration tested. To determine the effect of thiol-based antioxidants, cells were cotreated with Mn2+ and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) or glutathione (GSH) at the concentrations indicated in each figure. Survival was calculated as described above.

2.4. Mutation Analysis

The effect of Mn2+ on the accumulation of mutations was assessed by the CAN1 forward mutation assay and the lys2-10A mutation reversion as previously described [30, 31]. Mutation rates were determined by fluctuation analysis using at least five independent colonies [29, 32]. Each fluctuation test was repeated at least three times. The CAN1 forward mutation assay relies on the introduction of mutations on the CAN1 gene which encodes the arginine permease allowing mutant cells to grow on plates containing the toxic arginine analog, canavanine. The lys2-10A reversion assay is based on the restoration of the open-reading frame in a mononucleotide run of 10 adenines within the lys2 allele of strain RDKY3590 (Table 1), allowing mutant cells to grow on plates lacking lysine.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study.

| Gene | ORF | Function |

|---|---|---|

| HSP104 | YLL026W | Protein disaggregase |

| RAD2 | YGR258C | Nucleotide excision repair endonuclease |

| RAD52 | YML032C | Homologous recombination |

| SOD2 | YHR008C | Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase |

| RAD18 | YCR066W | Postreplication repair |

| CTA1 | YDR256C | Catalase activity |

| SOD1 | YJR104C | Superoxide dismutase activity |

| MLH1 | YMR167W | Mismatch repair |

| GSH2 | YOL049W | Glutathione synthetase activity |

| GSH1 | YJL101C | Glutamate-cysteine ligase activity |

| APN1 | YKL114C | Base excision repair |

| UBC13 | YDR092W | DNA postreplication repair |

| RAD27 | YKL113C | Base excision repair, DNA replication |

| RAD30 | YDR419W | Bypass synthesis DNA polymerase |

| NTG1 | YAL015C | Base excision repair |

Wild type: strain BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0).

RDKY3590 (MATa, ura3-52, leu2D1, trp1D63, hom3-10; lys210A).

2.5. DNA Sequence Analysis

Spectrum analysis was carried out by selecting mutants (Canr) on selective minimum media drop-out plates containing canavanine [29]. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from the mutants and the relevant region of CAN1 was amplified by PCR and sequenced [30]. Sequence was carried out at MCLAB (San Francisco, CA, USA). Sequence analysis was carried out using Sequencher (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis and graphing were performed using the GraphPad Prism 4 software package. Specific analysis for each experiment is indicated in each figure legend. In most cases, the mean of at least three experiments is plotted together with the standard deviation. Differences between mean values and multiple groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sensitivity of S. cerevisiae Strains to Mn2+

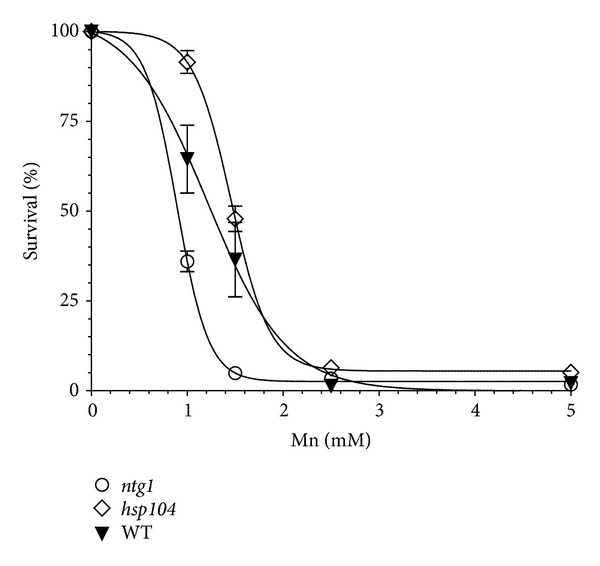

To perform a comparative analysis of the differential sensitivity of yeast strains, we first determined the dose of Mn2+ appropriate for the study. We initially used the wild type strain to determine the range of Mn2+ concentrations and found that there was a linear response in a narrow window between 1 and 2.5 mM (Figure 1), with the higher concentration resulting in viability below 5%, which did not significantly increase at higher concentrations of Mn2+. All selected strains were then exposed to this range of Mn2+ concentrations. Figure 1 shows a comparison between the wild type strain, the disaggregase hsp104 mutant, which displays higher tolerance to Mn2+, and the base excision repair ntg1 mutant, which is more sensitive. Mn2+ at 1.5 mM was determined to be the optimal concentration for the strain comparison (Figure 1). At this concentration, wild-type cells displayed approximately 40% survival and sensitive strains showed higher sensitivity relative to the wild-type strain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent response of selected yeast strains to Mn2+. Wild-type parental strain (BY4741) was tested for growth on media after exposure to 0, 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, and 5 mM Mn2+ as indicated in Materials and Methods. Survival was determined by counting the number of colonies in the respective dilutions and calculated based on the growth of cells not exposed to Mn2+ (100% survival). Mutant strains ntg1 and hsp104 that display increased and reduced sensitivity to Mn2+, respectively, are shown for comparison. The curve was fitted by nonlinear Sigmoidal dose response (variable slope).

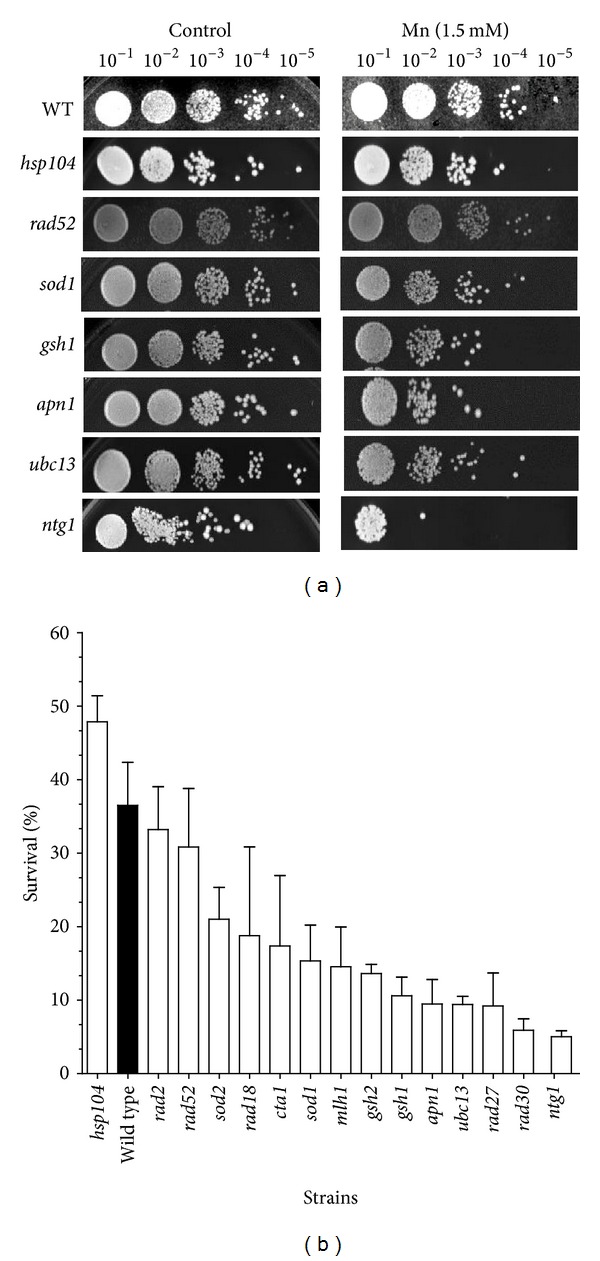

Based on published evidence and a recent report by Stephenson et al. [18], we selected several mutant strains that play a role in the mutagenicity avoidance and may be involved in processing Mn2+-induced DNA damage (Table 1). These mutants strains include those defective in nucleotide excision repair (rad2), postreplication repair (rad18, rad27a, and ubc13), base excision repair (apn1, rad27, and ntg1), homologous recombination (rad52), DNA mismatch repair (mlh1), and DNA damage bypass (rad30), glutathione synthesis (gsh1 and gsh2), oxidative stress (sod1, sod2, and cta1), and protein disaggregation (hsp104). Quantitative analysis involved exposing the cells to Mn2+ as described under Materials and Methods and spotting serial dilutions onto nonselective media YPD for colony counting. As observed in Figure 2(a), no significant difference was observed on the growth rate of each strain in the absence of Mn2+ (control panel), except for slow growing strain ntg1. However, upon treatment with Mn2+, the strains displayed differential sensitivity to the metal. All strains tested were sensitive to Mn2+ however, only the hsp104 mutant displayed less sensitivity than the wild type (48% versus 37%; Figure 2(b), black bar). No significant difference between rad2 (33.2% survival) and the wild type was observed, suggesting that Mn2+-induced DNA damage does not result in bulky adducts that require NER for processing. Similarly, no significant difference between rad52 (31% survival) and the wild type indicates that no significant DNA damage is processed to DNA double-strand breaks that require homologous recombination for repair. Interestingly, the oxidative stress mutants sod1, sod2, and cta1, (15%, 21%, and 17% survival, resp.) were approximately 2-fold more sensitive than wild type and the glutathione synthesis mutants gsh1 and gsh2 (10.6% and 13.6% survival, resp.) were 3-fold more sensitive. Mismatch repair mutants mlh1 displayed 14.5% survival, suggesting that Mn2+ induces an increased load of mismatches that cannot be repaired. More striking was the sensitivity of the base excision repair mutants apn1, rad27, and ntg1, (9.5%, 9.2%, and 4.9% survival), which were over 4-fold more sensitive to Mn2+ than wild type (Figure 2(b)), with ntg1 being the most sensitive (7.5-fold). In addition, ubc13 and rad30 mutants were also highly sensitive (~4-fold higher than wild type), further suggesting the generation of Mn2+-induced DNA damage.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity of yeast strains to Mn2+. (a) The survival of the strains in 1.5 mM Mn2+ was determined as described in Section 2. Serial dilutions (1 : 10–1 : 105) of treated cultures were spotted on YPD plates. Growth was scored after 3 days of incubation at 30°C. The serial dilutions of the strains are shown. (b) Quantification of the survival of the tested strains. Survival was determined by counting the number of colonies in the respective dilutions and calculated based on the growth of strains not treated with Mn2+. Strains are presented as being ordered from least to more sensitive. Wild-type strain is depicted by a black bar.

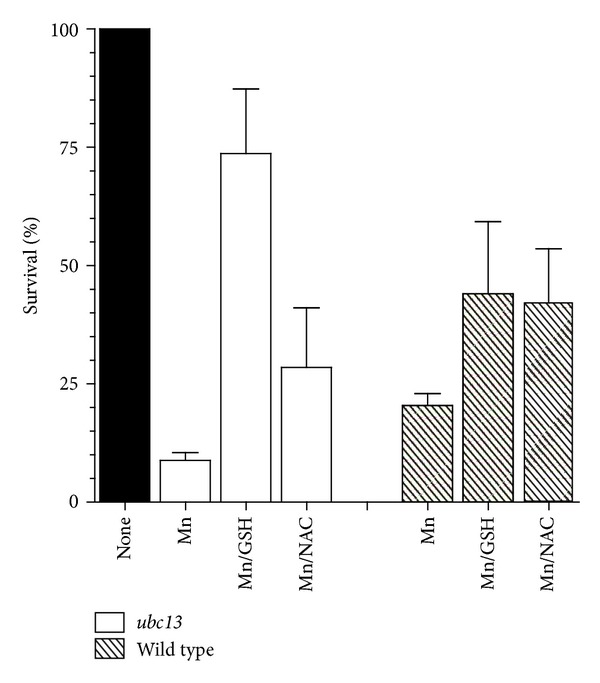

3.2. Attenuation of the Sensitivity to Mn2+ by Exogenous Antioxidants

Considering that oxidative stress mutants sod1, sod2, and cta1 and glutathione synthesis mutants gsh1 and ghs2 displayed higher sensitivity to Mn2+ than wild-type, we tested if antioxidants would protect from Mn2+-induced cytotoxicity. As shown in Figure 3, exogenously added NAC and GSH protected both the wild-type and the hypersensitive strain ubc13. The concentration of Mn2+ was increased to 2 mM to effectively determine the protective effects of the antioxidants on wild-type cells, resulting in 20% survival. Cotreatment of wild-type cells with 2 mM Mn2+ and 20 mM NAC increased the survival to 42%, a 2-fold increase (Figure 3). Similarly, cotreatment with 10 mM GSH increased survival to 44%, a 2-fold increase (Figure 3). To test the protective effect of NAC and GSH on a sensitive strain, we selected ubc13, which displayed 9% survival when treated with 1.5 mM Mn2+. Cotreatment with 20 mM NAC and 1.5 mM Mn2+ increased its survival to 28.5%, a 3-fold increase. Cotreatment with 1.5 mM Mn2+ and 10 mM GSH resulted in 74% survival, an 8.4-fold increase (Figure 3). It should be noted that cotreatment with either NAC or GSH alone did not have an effect on the growth of ubc13 or wild-type strains.

Figure 3.

Attenuation of the cytotoxic effect of Mn2+ by exogenous antioxidants. Sensitive strain ubc13 was treated with 1.5 mM Mn2+, 1.5 mM Mn2+ plus 10 mM glutathione (GSH), and 1.5 mM Mn2+ plus 20 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC), as described in Section 2. Survival was determined relative to untreated strain (100% survival). Wild-type strain was treated with 2 mM Mn2+, with or without cotreatment with GSH and NAC, as described in Section 2. At least 5 independent colonies were tested. Average survival plus standard deviation is shown.

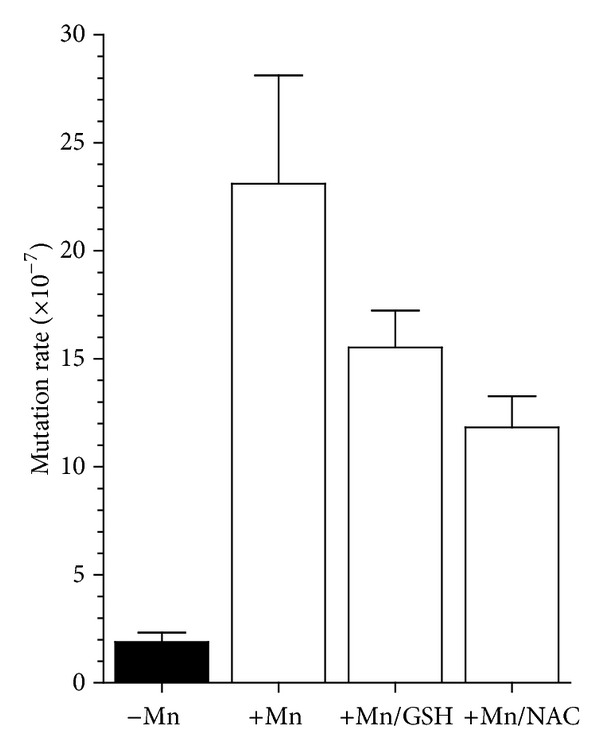

3.3. Analysis of the Mn2+-Induced Mutator Phenotype of Yeast

The mutagenicity of Mn2+ has been extensively documented [19]. To determine the extent to which exposure to Mn2+ increases the accumulations of mutations and to quantify the increase in the mutation rate of wild-type yeast cells, we utilized the CAN1 forward mutation assay [33], as described in Section 2. As shown in Figure 4, the mutation rate increased 12-fold (from 1.9 × 10−7 to 23.1 × 10−7) when wild-type cells were treated with 1.5 mM Mn2+. Based on the ability of antioxidants to reduce the toxicity of Mn2+ (Figure 3), we tested if cotreatment with NAC or GSH could also reduce the Mn2+-induced increase of the mutation rate. In fact, 20 mM NAC reduced the mutation rate by 1.5-fold (from 23.1 × 10−7 to 15.5 × 10−7), while 10 mM GSH reduced the mutation rate by 2-fold (from 23.1 × 10−7 to 11.8 × 10−7), consistent with the ability of these antioxidants to reduce Mn-induced toxicity (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Effect of Mn2+ on the mutation rate of the CAN1 forward mutation assay. The CAN1 assay detects any mutation which inactivates the CAN1 gene (arginine permease) and allows cells to grow on plates containing the toxic arginine analog, canavanine. The assay was performed using the wild-type strain in the presence of 1.5 mM Mn2+ or cotreated with 1.5 mM Mn2+ and 10 mM GSH or 1.5 mM Mn2+ and 10 mM NAC as indicated. Appearance of colonies on canavanine containing plates is scored and mutation rates are determined as described in Section 2. and standard deviation is included at the top of each bar.

3.4. Mutation Spectrum of CAN-Resistant Mutants

The CAN1 forward mutations assay provides a useful tool to identify the nature of the mutations that are generated from Mn2+ exposure. For this purpose, we amplified the CAN1 gene from canavanine-resistant colonies treated with 1.5 mM Mn2+ and completely sequenced the ORF to identify the mutation. Table 2 shows the spectrum of mutations of 20 independent canavanine-resistant colonies. A single mutation was identified in each isolate. Mutations are indicated first by the original base, its numerical sequence position, followed by the mutant base. The majority (70%) of the mutations were base-substitution mutations with 40% (8/20) being transitions and 30% transversions (6/20). The rest (30%) were frameshift mutations, of which 10% (2/20) were insertions and 20% (4/20) were deletions of single nucleotides at the position indicated. No complex mutations such as large deletions, insertions, duplications, or gross chromosomal rearrangements were found. No hotspot was found, although some base-substitution mutations were observed twice (G1196A, G1555A and A1417T; Table 2).

Table 2.

CAN1 mutation spectrum of wild-type yeast exposed to Mn2+.

| Base substitution mutations | |

|---|---|

| Transitions (8/20) | Transversions (6/20) |

| G522A G550A C623T G670A G1196A(×2) G1555A (×2) |

A312T A375C T380G A1417T (×2) A1645T |

|

| |

| Frameshift mutations | |

| Insertions (2/20) | Deletions (4/20) |

|

| |

| T740 T628 |

C417 T1143 G1259 G1474 |

3.5. Mn2+-Induced Reversion Mutations in the lys2-10A Allele Which Can Be Reduced by Mg2+

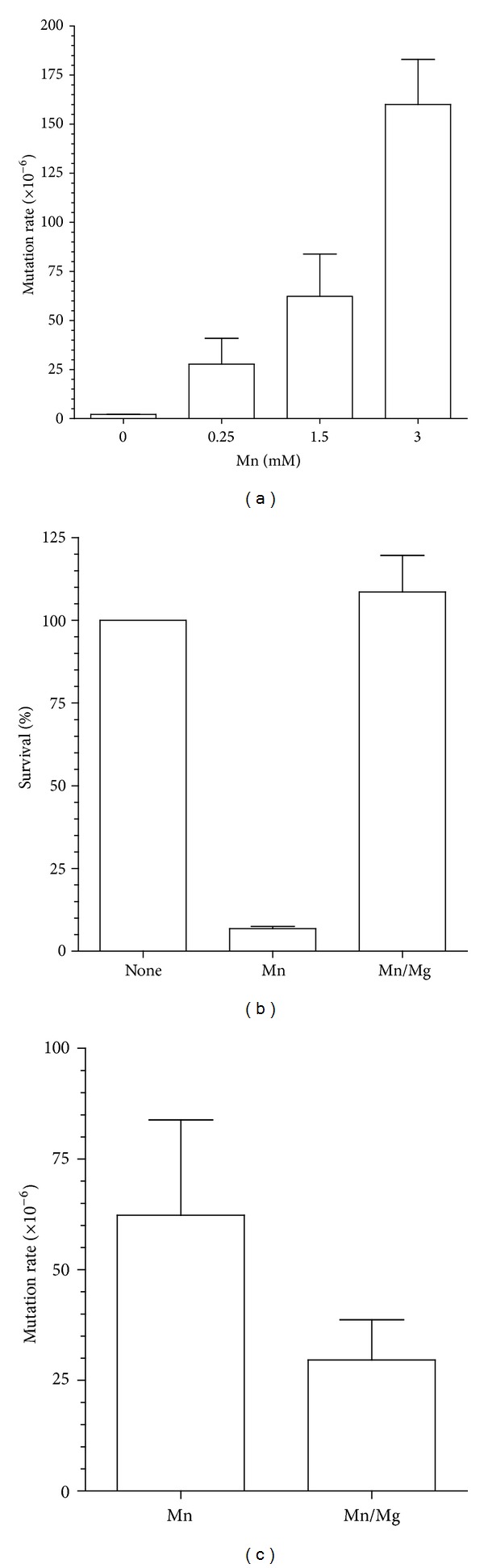

The Mn2+-induced accumulation of frameshift mutations prompted us to investigate if Mn2+ may be promoting polymerase slippage. For this purpose, we treated a yeast strain carrying the lys2-10A allele, where the LYS2 gene has a mononucleotide run of 10 adenines resulting in an out-of-frame gene, which can be restored by a frameshift mutation. We observed a dose-dependent increase in the mutation rate of this strain with increasing concentrations of Mn2+ (Figure 5(a)). Even at low concentrations of Mn2+ (0.25 mM), the mutation rate increased by 13-fold (from 2.1 × 10−6 to 27.8 × 10−6) and was 30-fold (2.1 × 10−6 to 62.3 × 10−6) and 76-fold (2.1 × 10−6 to 160 × 10−6) higher at 1.5 mM and 3 mM concentrations of Mn2+, respectively (Figure 5(a)). To determine if Mn2+ was displacing Mg2+ in the DNA synthesis reaction, we tested if exogenously added Mg2+ could both increase the survival of the strain as well as reduce its mutator phenotype. As shown in Figure 5(b), cotreatment of the strain with 1.5 mM Mn2+ and 10 mM Mg2+ significantly increased the survival to 100% (figure) and reduced the mutation rate by 2-fold (Figure 5(c)).

Figure 5.

Effect of Mn2+ and Mg2+ on the mutation rate of the reversion of the lys2-10A allele. (a) Mutation rates determination by the yeast mutator assay using a strain carrying the lys2-10A allele was performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of Mn2+. The appearance of Lys+ revertant colonies indicates a mutator phenotype. Rates are calculated as described in Section 2 and standard deviation is included at the top of each bar. (b) Cotreatment with 10 mM Mg2+ protects cells from the toxicity of Mn2+. Survival was determined as described in Section 2. (c) Cotreatment with 10 mM Mg2+ reduces the accumulation of mutations on the lys2-10A allele induced by 1.5 mM Mn2+. Each bar corresponds to the average of three sets of experiments using five independent colonies per set.

4. Discussion

Manganese is an essential trace metal required for normal physiological function. However, excess Mn exposure is associated with several disease states. Significant research focuses on chronic exposure to Mn which has been shown to cause manganism [10], a neurological disease referred to as idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD) that presents symptoms resembling the dystonic movement associated with Parkinson's disease (PD) [11–13]. Numerous studies suggest that the neurotoxicity as a result of Mn exposure is a consequence of a variety of factors including apoptosis, oxidative injury, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation [14–18]. Of particular interest is the mutagenicity of Mn. Despite extensive knowledge of the DNA damaging properties of Mn, little is known about the pathways involved in the response and repair of Mn-induced DNA damage.

In the present work, we investigate the contribution of various DNA repair pathways to the survival of yeast cells exposed to Mn toxicity. We selected mutant strains in key components of the major DNA repair pathways, as described in Table 2. Initial observation indicates that yeast cells are relatively tolerant to Mn2+, displaying reduced viability only when concentrations reach over 1 mM (Figure 2), which is several orders of magnitude higher than for other metals, such as Cd2+, which is toxic at the μM level [31]. Interestingly, the sensitivity of yeast cells to Mn2+ is almost complete when the concentration of Mn2+ reaches 2.5 mM (Figure 2) displaying a linear response within this concentration window. For this reason, the strain comparison was performed at the 1.5 mM concentration. All strains displayed varying degrees of sensitivity, and all except the hsp104 strain, were more sensitive than the wild type, suggesting that no significant toxic levels of protein aggregation are induced by Mn2+.

Cells possess three major excision repair pathways: (i) base excision repair (BER) which is responsible for the repair of damaged bases resulting primarily from oxidative damage [34], (ii) nucleotide excision repair (NER) which plays a major role in the repair of large DNA adducts and UV damaged DNA [35, 36], and (iii) DNA mismatch repair (MMR), a postreplicative mechanism, improves the fidelity of DNA replication by removing misincorporated bases by the DNA polymerase [37]. In addition, cells possess recombination repair, which in yeast is primarily performed by homologous recombination (HR) [38]. These pathways act in concert to respond to exogenous damage and guarantee genome stability. Some of these pathways have been shown to be defective in neurodegenerative diseases [39, 40] and participate in response to neurotoxic agents [41, 42]. Our data suggests that BER plays a major role in the cellular response to toxic levels of Mn2+ as mutants apn1, rad27, and ntg1 were more than 4-fold sensitive to Mn2+ than wild type (Figure 2(b)) and ntg1 was the most sensitive (7.5-fold). NTG1 is a DNA N-glycosylase which removes the oxidized damaged base on both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA [43]. The DNA damage generated by Mn2+ appears to interfere with DNA replication, as indicated by the high sensitivity of strains ubc13, a DNA-damage-inducible gene, member of the error-free postreplication repair pathway [44], and rad30 mutants, which are defective in translesion synthesis DNA polymerase eta, required for bypass synthesis at sites where replication forks are stalled due to damaged bases. Conversely, NER does not appear to play a major role in the repair of Mn2+-induced DNA damage, as indicated by similar survival of rad2 mutant to the wild type. Similarly, the lack of a strong Mn2+-induced phenotype in the rad52 strain suggests that no significant DNA damage is processed to DNA double-strand breaks, which requires homologous recombination for repair.

It appears that oxidative stress plays a major role in Mn2+ cytotoxicity as indicated by the increased sensitivity of the superoxide dismutase (sod1 and sod2) and catalase mutants (cta1). This is further supported by the ability of NAC to improve the survival of the wild-type strain and the DNA repair strain ubc13 (Figure 3). Exogenous addition of glutathione, which serves both as a reducing agent and a chelator to Mn, further protected the strains from Mn2+ exposure.

A significant increase in the accumulation of mutations was observed in cells exposed to Mn2+, using two distinct mutator assays. The CAN1 forward mutation assay indicated a 12-fold increase in the mutation rate when cells were exposed to 1.5 mM Mn2+. Similar to the effect on survival, NAC and GSH reduced the increase in the mutation rate, suggesting that the mutations are at least the result of oxidative damage to DNA. Analysis of the mutations in the CAN1 gene in these yeast cells indicates that most base substitutions are accumulated (70%), while 30% were frameshifts mutations. In combination with the increased mutation rate, cells exposed to Mn2+ have a significantly higher accumulation of frame shift mutations. This is distinct from spontaneous mutations (not exposed to Mn2+), where 10% of the mutants analyzed had complex mutations [29, 45]. The increase in frameshift mutations was also observed when the mutation rate was measured using the lys2-10A allele. This increase was dose-dependent and ameliorated by Mg2+, concomitant with an increase in cell survival. In fact, Mg2+ has been shown to protect cells from Mn2+ toxicity [46–48]. It is possible that the mutation rate increase is the result of Mn2+ intoxication of the DNA polymerase by displacing Mg2+ [21], which would require MMR for repair, explaining the increased sensitivity of the mlh1 strain.

The adverse effect of Mn2+ in DNA polymerase fidelity has been previously reported [21] and proposed to be due to replacement of Mg2+, which is essential in the reaction. However, recently, a series of studies have shown that some viral polymerases, such as those of coronavirus [49] and poliovirus [50], have exclusive requirement for Mn+2 in their synthetic activity. Similarly, the incorporation of nonnucleoside triphosphate analogs is accomplished by X family DNA polymerases in an Mn-dependent manner [51], while cellular error-prone DNA polymerase iota, isolated from tumor cells, was shown to utilize Mn2+ [52] in DNA synthesis. This is an interesting observation because DNA polymerase iota is inducible by Mn2+ and could in part contribute to the mutagenesis observed in Mn2+ exposed cells.

Most published work on the toxicity of manganese has focused on Mn2+, while there was some claim that Mn3+ was the toxic species. However, recent work indicates that Mn3+ has a significantly reduced toxicity compared to Mn2+ [53, 54]. In addition, since manganese has a similar ionic radius to calcium, Mn2+ has been shown to interfere with Ca2+ metabolism [19, 55]. However, there are no reports of Ca2+ having an effect on BER.

The data presented in this study indicates that Mn2+-induced DNA damage is in part due to oxidative stress and requires base excision repair. Considering the well-known relationship between DNA repair defects and neurodegenerative diseases, and the involvement of DNA repair in response to neurotoxic agents, the status of base excision repair, or some of its key components, may prove to be useful as biomarkers to determine the susceptibility to toxic damage from excess exposure to Mn2+. There is currently a lack of well-validated biomarkers for manganese exposure. Manganese overexposure leads to cognitive, motor, behavioral effects in children [56] and manganese is associated with Parkinson's disease in adults [11–13]. Persons most likely to be exposed to excessive levels of manganese are manganese coal miners and welders. However, there is currently no way to determine who will suffer severe effects after Mn overexposure. Thus, preventive strategies and biomarker development for BER status are strongly supported by our findings. An assay that monitors the BER status of exposed individuals could be used in conjunction with other recently proposed biomarkers for Mn exposure which measure delta-amino levulinic acid levels [57] and the Mn/Fe ratio [58]. While these two biomarkers can detect exposure to Mn, an assay evaluating BER status would be of more value as a preventative strategy with its inherent potential to distinguish individuals who would be more severely affected by Mn exposure from those who would not.

Authors' Contribution

Adrienne P. Stephenson and Tryphon K. Mazu shared equally in this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the Gene and Cell Manipulation Facility of Florida A&M University. This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health through Grant nos. 2 G12 RR003020 and 8 G12 MD007582-28. They appreciate the support from the following funding agencies: Association of Minority Health Professions Schools, Inc. (AMPHS) and the ATS/DR Cooperative Agreement no. 3U50TS473408-05W1/CFDA and no. 93.161 (RRR) NIEHS/ARCH 5S11ES01187-05 (RRR).

References

- 1.Prohaska JR. Functions of trace elements in brain metabolism. Physiological Reviews. 1987;67(3):858–901. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.3.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley LS. The roles of trace elements in foetal and neonatal development. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 1981;294:145–152. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurley LS, Keen CL, Baly DL. Manganese deficiency and toxicity: effects on carbohydrate metabolism in the rat. NeuroToxicology. 1984;5(1):97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wedler FC. 3 Biological significance of manganese in mammalian systems. Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. 1993;30:89–133. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Environmental Protection Agency. National Center for Environmental Assessment. 1999.

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Toxicological Profile for Manganese. Atlanta, Ga, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1992. (The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Ed.). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray LE, Jr., Laskey JW. Multivariate analysis of the effects of manganese on the reproductive physiology and behavior of the male house mouse. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 1980;6(4):861–867. doi: 10.1080/15287398009529904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mergler D, Baldwin M. Early manifestations of manganese neurotoxicity in humans: an update. Environmental Research. 1997;73(1-2):92–100. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1997.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wennberg A, Iregren A, Struwe G, Cizinsky G, Hagman M, Johansson L. Manganese exposure in steel smelters a health hazard to the nervous system. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health. 1991;17(4):255–262. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aschner M, Dorman DC. Manganese: pharmacokinetics and molecular mechanisms of brain uptake. Toxicological Reviews. 2006;25(3):147–154. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200625030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guilarte TR. Manganese and Parkinson’s disease: a critical review and new findings. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118(8):1071–1080. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calne DB, Chu N-S, Huang C-C, Lu C-S, Olanow W. Manganism and idiopathic parkinsonism: similarities and differences. Neurology. 1994;44(9):1583–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Normandin L, Hazell AS. Manganese neurotoxicity: an update of pathophysiologic mechanisms. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2002;17(4):375–387. doi: 10.1023/a:1021970120965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stredrick DL, Stokes AH, Worst TJ, et al. Manganese-induced cytotoxicity in dopamine-producing cells. NeuroToxicology. 2004;25(4):543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C-J, Liao S-L. Oxidative stress involves in astrocytic alterations induced by manganese. Experimental Neurology. 2002;175(1):216–225. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seth K, Agrawal AK, Date I, Seth PK. The role of dopamine in manganese-induced oxidative injury in rat pheochromocytoma cells. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 2002;21(3):165–170. doi: 10.1191/0960327102ht228oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Worley CG, Bombick D, Allen JW, Lee Suber R, Aschner M. Effects of manganese on oxidative stress in CATH.a cells. NeuroToxicology. 2002;23(2):159–164. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephenson AP, Schneider JA, Nelson BC, et al. Manganese-induced oxidative DNA damage in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells: attenuation of thymine base lesions by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Toxicology Letters. 2013;218:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerber GB, Léonard A, Hantson P. Carcinogenicity, mutagenicity and teratogenicity of manganese compounds. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2002;42(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Meo M, Laget M, Castegnaro M, Dumenil G. Genotoxic activity of potassium permenganate in acidic solutions. Mutation Research. 1991;260(3):295–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(91)90038-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckman RA, Mildvan AS, Loeb LA. On the fidelity of DNA replication: manganese mutagenesis in vitro. Biochemistry. 1985;24(21):5810–5817. doi: 10.1021/bi00342a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olivier P, Marzin D. Study of the genotoxic potential of 48 inorganic derivatives with the SOS chromotest. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology. 1987;189(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(87)90057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orgel A, Orgel LE. Induction of mutations in bacteriophage T4 with divalent manganese. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1965;14(2):453–457. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putrament A, Baranowska H, Prazmo W. Induction by manganese of mitochondrial antibiotic resistance mutations in yeast. Molecular and General Genetics. 1973;126(4):357–366. doi: 10.1007/BF00269445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prazmo W, Balbin E, Baranowska H. Manganese mutagenesis in yeast. II. Conditions of induction and characteristics of mitochondrial respiratory deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants induced with manganese and cobalt. Genetical Research. 1975;26(1):21–29. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300015810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bornhorst J, Ebert F, Hartwig A, Michalke B, Schwerdtle T. Manganese inhibits poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in human cells: a possible mechanism behind manganese-induced toxicity? Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 2010;12(11):2062–2069. doi: 10.1039/c0em00252f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marzin DR, Phi HV. Study of the mutagenicity of metal derivatives with Salmonella typhimurium TA102. Mutation Research. 1985;155(1-2):49–51. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(85)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alani E, Reenan RAG, Kolodner RD. Interaction between mismatch repair and genetic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1994;137(1):19–39. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tishkoff DX, Filosi N, Gaida GM, Kolodner RD. A novel mutation avoidance mechanism dependent on S. cerevisiae RAD27 is distinct from DNA mismatch repair. Cell. 1997;88(2):253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flores-Rozas H, Kolodner RD. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH3 gene functions in MSH3-dependent suppression of frameshift mutations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(21):12404–12409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banerjee S, Flores-Rozas H. Cadmium inhibits mismatch repair by blocking the ATPase activity of the MSH2-MSH6 complex. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(4):1410–1419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsischky GT, Filosi N, Kane MF, Kolodner R. Redundancy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH3 and MSH6 in MSH2-dependent mismatch repair. Genes and Development. 1996;10(4):407–420. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ekwall K, Ruusala T. Budding yeast CAN1 gene as a selection marker in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Research. 1991;19(5):p. 1150. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dianov GL, Hubscher U. Mammalian base excision repair: the forgotten archangel. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:3483–3490. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diderich K, Alanazi M, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Premature aging and cancer in nucleotide excision repair-disorders. DNA Repair. 2011;10(7):772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugasawa K. Regulation of damage recognition in mammalian global genomic nucleotide excision repair. Mutation Research. 2010;685(1-2):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preston BD, Albertson TM, Herr AJ. DNA replication fidelity and cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2010;20(5):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amunugama R, Fishel R. Homologous recombination in eukaryotes. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2012;110:155–206. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387665-2.00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds JJ, Stewart GS. A single strand that links multiple neuropathologies in human disease. Brain. 2013;136:14–27. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeppesen DK, Bohr VA, Stevnsner T. DNA repair deficiency in neurodegeneration. Progress in Neurobiology. 2011;94(2):166–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruman II, Henderson GI, Bergeson SE. DNA damage and neurotoxicity of chronic alcohol abuse. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2012;237:740–747. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2012.011421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doi K. Mechanisms of neurotoxicity induced in the developing brain of mice and rats by DNA-damaging chemicals. Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2011;36(6):695–712. doi: 10.2131/jts.36.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alseth I, Eide L, Pirovano M, Rognes T, Seeberg E, Bjørås M. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologues of endonuclease III from Escherichia coli, Ntg1 and Ntg2, are both required for efficient repair of spontaneous and induced oxidative DNA damage in yeast. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(5):3779–3787. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brusky J, Zhu Y, Xiao W. UBC13, a DNA-damage-inducible gene, is a member of the error-free postreplication repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Current Genetics. 2000;37(3):168–174. doi: 10.1007/s002940050515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau PJ, Flores-Rozas H, Kolodner RD. Isolation and characterization of new proliferating cell nuclear antigen (POL30) mutator mutants that are defective in DNA mismatch repair. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22(19):6669–6680. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6669-6680.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blackwell KJ, Tobin JM, Avery SV. Manganese uptake and toxicity in magnesium supplemented and unsupplemented Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1997;47(2):180–184. doi: 10.1007/s002530050909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malcová R, Gryndler M, Vosátka M. Magnesium ions alleviate the negative effect of manganese on Glomus claroideum BEG23. Mycorrhiza. 2002;12(3):125–129. doi: 10.1007/s00572-002-0161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters A, Lofts S, Merrington G, Brown B, Stubblefield W, Harlow K. Development of biotic ligand models for chronic manganese toxicity to fish, invertebrates, and algae. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2011;30(11):2407–2415. doi: 10.1002/etc.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahn DG, Choi JK, Taylor DR, Oh JW. Biochemical characterization of a recombinant SARS coronavirus nsp12 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase capable of copying viral RNA templates. Archives of Virology. 2012;157:2095–2104. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1404-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crotty S, Gohara D, Gilligan DK, Karelsky S, Cameron CE, Andino R. Manganese-dependent polioviruses caused by mutations within the viral polymerase. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(9):5378–5388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5378-5388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crespan E, Zanoli S, Khandazhinskaya A, et al. Incorporation of non-nucleoside triphosphate analogues opposite to an abasic site by human DNA polymerases β and λ . Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(13):4117–4127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lakhin AV, Efremova AS, Makarova IV, et al. Effect of Mn(II) on the error-prone DNA polymerase iota activity in extracts from human normal and tumor cells. Molecular Genetics, Microbiology and Virology. 2013;28(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang P, Li G, Chen C, et al. Differential toxicity of Mn2+ and Mn3+ to rat liver tissues: oxidative damage, membrane fluidity and histopathological changes. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2012;64(3):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gunter TE, Gavin CE, Aschner M, Gunter KK. Speciation of manganese in cells and mitochondria: a search for the proximal cause of manganese neurotoxicity. NeuroToxicology. 2006;27(5):765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinsino A, Roccheri MC, Costa C, Matranga V. Manganese interferes with calcium, perturbs ERK signaling, and produces embryos with no skeleton. Toxicological Sciences. 2011;123(1):217–230. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zoni S, Lucchini RG. Manganese exposure: cognitive, motor and behavioral effects on children: a review of recent findings. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2013;25:255–260. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835e906b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andrade V, Mateus ML, Batoreu MC, Aschner M, Dos Santos AP. Urinary delta-ALA: a potential biomarker of exposure and neurotoxic effect in rats co-treated with a mixture of lead, arsenic and manganese. Neurotoxicology. 2013;38:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng W, Fu SX, Dydak U, Cowan DM. Biomarkers of manganese intoxication. NeuroToxicology. 2011;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]