Non-small cell lung cancer is a promising target for the next generation of immune-based strategies. In this article, we examine the current state of the art in lung cancer immunotherapy, including vaccines that specifically target lung tumor antigens and immune checkpoint antibodies. Immune-based strategies have shown initial promise for early and advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer, which must be validated in randomized studies.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Lung cancer, NSCLC, PD1, PD-L1, CTLA4, Vaccine, Immune checkpoint

Abstract

Introduction.

Immunotherapy has become an increasingly important therapeutic strategy for those with cancer, with phase III studies demonstrating survival advantages in melanoma and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a promising target for the next generation of immune-based strategies. In this article, we examine the current state of the art in lung cancer immunotherapy, including vaccines that specifically target lung tumor antigens and immune checkpoint antibodies such as antiprogrammed death 1 (anti-PD-1). Both approaches harness innate immunity against tumors by suppressing tumor-induced immune paresis.

Methods.

To identify relevant clinical trials of immunotherapy in NSCLC, PubMed and Medline databases were searched using the terms “immunotherapy” and “NSCLC,” and several other therapy-specific search terms (e.g., PD-1, NSCLC). Additionally, abstracts presented at international lung cancer symposia, the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, and the European Society of Medical Oncology annual meeting between 2005 and 2013 were evaluated.

Results.

Large international phase III trials of NSCLC vaccines have completed accrual in both the adjuvant and metastatic disease settings. Results of the START study were disappointing, but results from other studies are still awaited. Immune checkpoint modulation has shown promise, with separate phase I studies of the anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, and anti-PD-L1 antibody, MPDL3280A, demonstrating good tolerance and durable responses for certain patients with NSCLC who were heavily pretreated.

Conclusions.

Immune-based strategies have shown initial promise for early- and advanced-stage NSCLC. Validating these findings in randomized studies and discovering durable biomarkers of response represent the next challenges for investigation.

Implications for Practice:

Immunotherapy, particularly the use of monoclonal antibodies that block inhibitory immune checkpoint molecules and thus enhance the immune response to tumor, has shown promise for advanced solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, in recent years. We review the challenges and successes associated with harnessing the immune system to treat NSCLC using vaccine and immunomodulatory strategies and discuss recently reported data on durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1-directed therapies. Future directions in this rapidly evolving field are explored, including biomarker-driven strategies and combined treatments that have the potential to enhance cancer immunotherapy greatly.

Introduction

Recent progress in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has centered on the discovery of critical driver mutations harbored by some tumors. Specifically, targeting these mutations can deliver unprecedented benefits for patients with advanced lung cancer [1, 2]. Currently, however, in many NSCLC tumors (both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell), a significant oncogenic driver is not known, leaving cytotoxic therapy as the only available approved option for patients. These therapies have only moderate efficacy and are associated with significant toxicities [3]. For this reason, strategies such as immunotherapy, which may have efficacy irrespective of histology or mutational status, are particularly attractive. Although many attempts have been made over more than four decades to harness the immune system to treat NSCLC [4], significant breakthroughs are only now being realized. In this article, we will review novel vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors that are currently in clinical development for the treatment of both early- and advanced-stage NSCLC. For earlier-stage disease, melanoma-associated antigen-A3 (MAGE-A3) vaccine and liposomal BLP25 targeting mucinous glycoprotein 1 (MUC1) have shown promising results in phase II studies. Results from large phase III trials are awaited [5, 6]. In the advanced disease setting, phase III studies of belagenpumatucel-L, recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) vaccine, and the MUC1-directed vaccine, TG4010, are underway after encouraging phase II results [7–9]. Immunomodulatory methods and in particular immune checkpoint inhibition as a treatment for NSCLC have recently come to the forefront with the anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 antibody, ipilimumab, entering late-phase development for squamous NSCLC. Additionally, there are promising early phase results with antiprogrammed death-1 (anti-PD-1) agents including nivolumab (BMS-936558) and lambrolizumab (MK-3475) [10–12]. Finally, the need for appropriate endpoints for patients receiving immunotherapy and the development of biomarkers to predict response will be addressed.

Materials and Methods

In compiling data for this review, searches of the PubMed and Medline databases were conducted for published preclinical data and clinical trials, using the following search terms: immunotherapy and NSCLC, immune lung cancer, and other drug- and target-specific terms (e.g., PD-1, NSCLC). Abstracts presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology and European Society of Medical Oncology annual meetings and at international lung cancer symposia between 2005 and 2013 were reviewed. Relevant reports were extracted.

Immunology and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Immune surveillance is an essential mechanism in the prevention of cancer development and is dependent on the immune system recognizing nascent tumor antigens as foreign precursors of cancer and subsequently eliminating them. Central to this process is the expression of non-self-antigens by tumor cells as a result of aberrantly expressed or mutated genes, viral antigens, or overexpression of cellular antigens [13]. The immunoediting hypothesis is based on preclinical data showing that tumors developing in immunodeficient mice are inherently more immunogenic and consequently less able to develop independently than tumors that arise in immunocompetent hosts [14]. Immunoediting is thought to occur after intrinsic tumor suppressor mechanisms such as apoptosis have failed and neoplastic transformation has begun. It is comprised of three phases: elimination, equilibrium, and escape (Fig. 1) [15]. The initial elimination phase consists of the host's innate and adaptive immunity working to destroy incipient subclinical tumor. This phase is constantly happening in immunocompetent hosts and prevents development of cancer. Cancer cells that survive this phase enter equilibrium, where growth and metastasis are constrained by a competent immune system. However, resistant tumor variants may emerge and elude immunity, either through defective antigen expression, resistance to immune cytotoxicity, or by induction of immune paresis in the host. These resistant clones lead to clinically apparent cancers [16].

Figure 1.

The immunoediting hypothesis suggests that clinically evident cancer arises when the control mechanisms of the immune system are breached thus leading to escape and a cascade of tumor proliferation associated with relative immune paresis.

Renal cell carcinoma and melanoma are the tumors classically thought to be immunogenic, as evidenced by spontaneous regressions [17] and occasional dramatic and often durable responses to high-dose interleukin-2 [18]. Evidence for an immune role in NSCLC has been more subtle, but is emerging. High levels of CD4+/CD8+ T cells infiltrating resected NSCLC tumors have been associated with a favorable prognosis [19]; conversely, high levels of infiltrating immunosuppressive T-regulatory cells are associated with increased risk for relapse [20]. Recent data suggest that haplotypes and polymorphisms affecting cytokines and Fas ligand, respectively, may influence immune-mediated resistance to NSCLC propagation [21, 22].

High levels of CD4+/CD8+ T cells infiltrating resected NSCLC tumors have been associated with a favorable prognosis; conversely, high levels of infiltrating immunosuppressive T-regulatory cells are associated with increased risk for relapse. Recent data suggest that haplotypes and polymorphisms affecting cytokines and Fas ligand, respectively, may influence immune-mediated resistance to NSCLC propagation.

The immunomodulatory effect of currently approved therapies for NSCLC is also of interest. The exposure of antigens associated with cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced or EGF receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI)-induced tumor cell death is a logical priming strategy for an immune-based intervention. Combination of cytotoxic therapies with anti-angiogenic monoclonal antibodies, including bevacizumab, may also be synergistic [23].

Efforts to use molecules that stimulate dendritic cell maturation have been disappointing. Two recent phase III studies of the toll-like receptor agonist, PF-3512676, combined with first-line chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC were stopped early because of lack of efficacy and concerns for safety, including an increased risk for sepsis [24, 25]. Despite promising phase II data, talactoferrin failed to show a benefit as a single-agent versus placebo for pretreated advanced NSCLC in a recently reported phase III study [26–28].

Current immunotherapies in advanced clinical development for the treatment of NSCLC focus on stimulating an immune response to tumor antigens (e.g., the MAGE-A3 vaccine) or reducing immune tolerance to cancer cells by blocking inhibitory immune checkpoint molecules. This second strategy works to release the brakes on T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity (e.g., anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1).

Vaccines for Stage I–III NSCLC

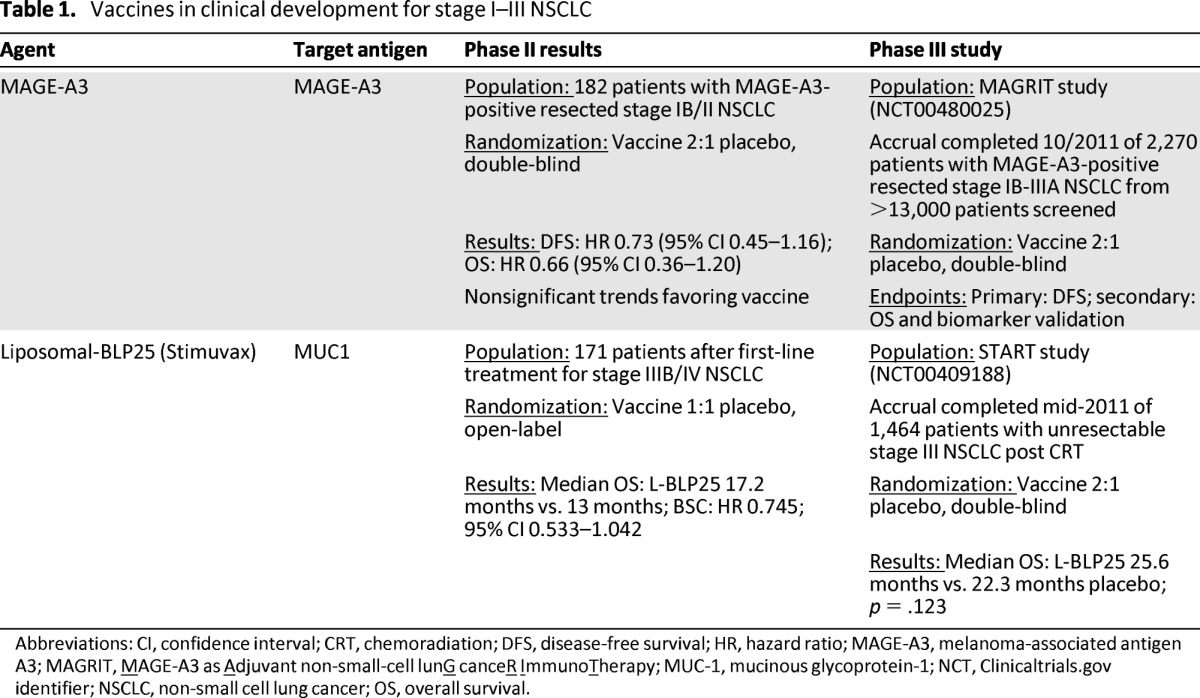

There are two vaccines in clinical development for the treatment of potentially curable NSCLC. The MAGE-A3 vaccine is used to treat resectable stage I–IIIA NSCLC and liposomal-BLP25 to treat stage III NSCLC after definitive chemoradiation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vaccines in clinical development for stage I–III NSCLC

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRT, chemoradiation; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; MAGE-A3, melanoma-associated antigen A3; MAGRIT, MAGE-A3 as Adjuvant non-small-cell lunG canceR ImmunoTherapy; MUC-1, mucinous glycoprotein-1; NCT, Clinicaltrials.gov identifier; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival.

MAGE-A3 Vaccine

MAGE-A3 is an antigen specifically associated with various solid tumors, including NSCLC. Studies indicate that 17%–50% of NSCLC tumors express MAGE-A3 on their surface and expression has been associated with a poor prognosis [29, 30]. The MAGE-A3 antigen-specific immunotherapeutic (ASCI) consists of purified MAGE-A3 recombinant protein in a liposomal formulation containing the AS15 adjuvant system. In a double-blind, phase II study, 182 patients with MAGE-A3-positive resected stage IB/II NSCLC were randomly assigned to vaccine or placebo in a 2:1 ratio (Table 1) [5, 31]. Patients received five doses of MAGE-A3 ASCI or placebo once every 3 weeks followed by a maximum of eight doses given once every three months [5]. Nonsignificant trends toward improved disease-free interval (DFI) (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.74), disease-free survival (DFS) (HR = 0.73), and overall survival (OS) (HR = 0.66), were noted for patients who received MAGE-A3 ASCI. Gene expression analysis of the tumors identified a signature of immune-related genes that appeared to be associated with a high risk for relapse. Patients without this signature had a <5% risk for relapse [32]. Another examined gene signature appeared to predict benefit from MAGE-A3 vaccination in NSCLC (as had been noted previously in melanoma) [32]. This signature has been incorporated as a secondary endpoint in the phase III MAGRIT (MAGE-A3 as Adjuvant non-small-cell lunG canceR ImmunoTherapy) study [32, 33]. The MAGRIT study screened more than 13,000 patients with resected stage IB–IIIA NSCLC for immunohistochemical expression of the MAGE-A3 antigen. Ultimately, 2,270 patients were accrued by October 2011 [30]. Prior adjuvant chemotherapy was not an exclusion criterion. Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to vaccine or placebo and therapy was administered three times a week for five weeks followed by every 12 weeks for eight doses [34]. Results from this study are expected in mid to late 2013.

Liposomal BLP25

MUC1 is a membrane-bound glycoprotein that becomes overexpressed and undergoes aberrant glycosylation with malignant transformation of diverse tumor types including NSCLC [35]. Liposomal BLP25 (L-BLP25) is a liposomal vaccine consisting of 25 amino acids from the immunogenic variable number of tandem-repeats region of MUC1 combined with an immunoadjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A [36].

In a phase II multicenter randomized clinical trial, 171 patients with stable or responding stage IIIB (38%) or IV (62%) NSCLC after first-line chemotherapy or after chemoradiation were randomly assigned to L-BLP25 plus best supportive care (BSC) or BSC alone [6]. Patients randomly assigned to the vaccine arm received a single low dose cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) infusion followed three days later by the first of eight weekly subcutaneous doses of L-BLP25. At the discretion of the investigator, patients could also receive maintenance vaccine injections once every six weeks starting six weeks after the last weekly vaccination and continuing until disease progression. Of patients on the vaccine arm, 69% received this maintenance schedule. The primary endpoint of the study was OS. L-BLP25 was well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events consisting of mild flu-like symptoms and no reported increase in serious adverse events (L-BLP25 plus BSC 26.1% vs. BSC 36.1%). Efficacy results suggested a nonsignificant trend toward improved OS for patients who received L-BLP25 (17.4 months vs. 13 months for BSC alone). However, it was noted that adjustment for stratification variables, including response to first-line therapy and stage, appeared to reduce this effect. In subgroup analysis, patients with locoregionally advanced stage IIIB disease appeared most likely to derive benefit from the vaccine (adjusted HR = 0.524; 95% CI, 0.261–1.052; p = .069) with a trend toward improved two-year survival (60% vs. 36.7% for BSC). However, it should be noted that this analysis was not a prespecified endpoint of the study. Updated analyses suggested a continued trend toward improved survival for vaccinated patients (median OS 30.6 months vs. 13.3 months) and no serious long-term safety issues [37].

Subsequently, the phase III START (Stimulating Targeted Antigenic Responses To NSCLC) trial randomly assigned 1,513 patients with unresectable stage IIIB NSCLC following definitive chemoradiation to L-BLP25 with BSC or placebo plus BSC [38]. This study, with a primary endpoint of OS and using the phase II vaccine schedule, completed accrual in November 2011. Unfortunately, START failed to meet its primary endpoint of improved OS with L-BLP25 (25.6 months vs. 22.3 months for placebo; p = .123), although analysis of a predefined secondary endpoint did suggest that patients who received concurrent chemoradiation may have derived some benefit from the addition of the vaccine (median OS for concurrent chemoradiation followed by vaccine: 30.8 months vs. 20.6 months for concurrent chemoradiation followed by placebo; p = .016) [39]. In Asia, the smaller phase III INSPIRE study, with a design and patient population similar to that of START, began enrollment in December 2009 and is ongoing [40]. In the United States, an ongoing phase II study is examining the combination of L-BLP25 with bevacizumab after chemoradiation for stage III NSCLC [41]. Potential biomarkers of response to L-BLP25 have yet to be described in the literature, and in the setting of the negative phase III START trial, further development of BLP25 will be particularly challenging.

Vaccines for Advanced NSCLC

Belagenpumatucel-L

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) is a multifunctional cytokine that works in normal and neoplastic cells to promote epithelial differentiation and inhibit cell growth [42]. Defective TGF-beta-mediated signaling has been associated with a more aggressive phenotype and poorer survival in advanced NSCLC, and elevated levels have also been linked to immunosuppression and a poor prognosis [43]. Belagenpumatucel-L is an allogeneic whole-cell vaccine comprised of four irradiated NSCLC cell lines (two adenocarcinoma, one squamous, and one large cell), that transfects cells with a TGF-beta2 antisense gene. TGF-beta2 is thus downregulated and tumor antigen recognition is potentiated [7].

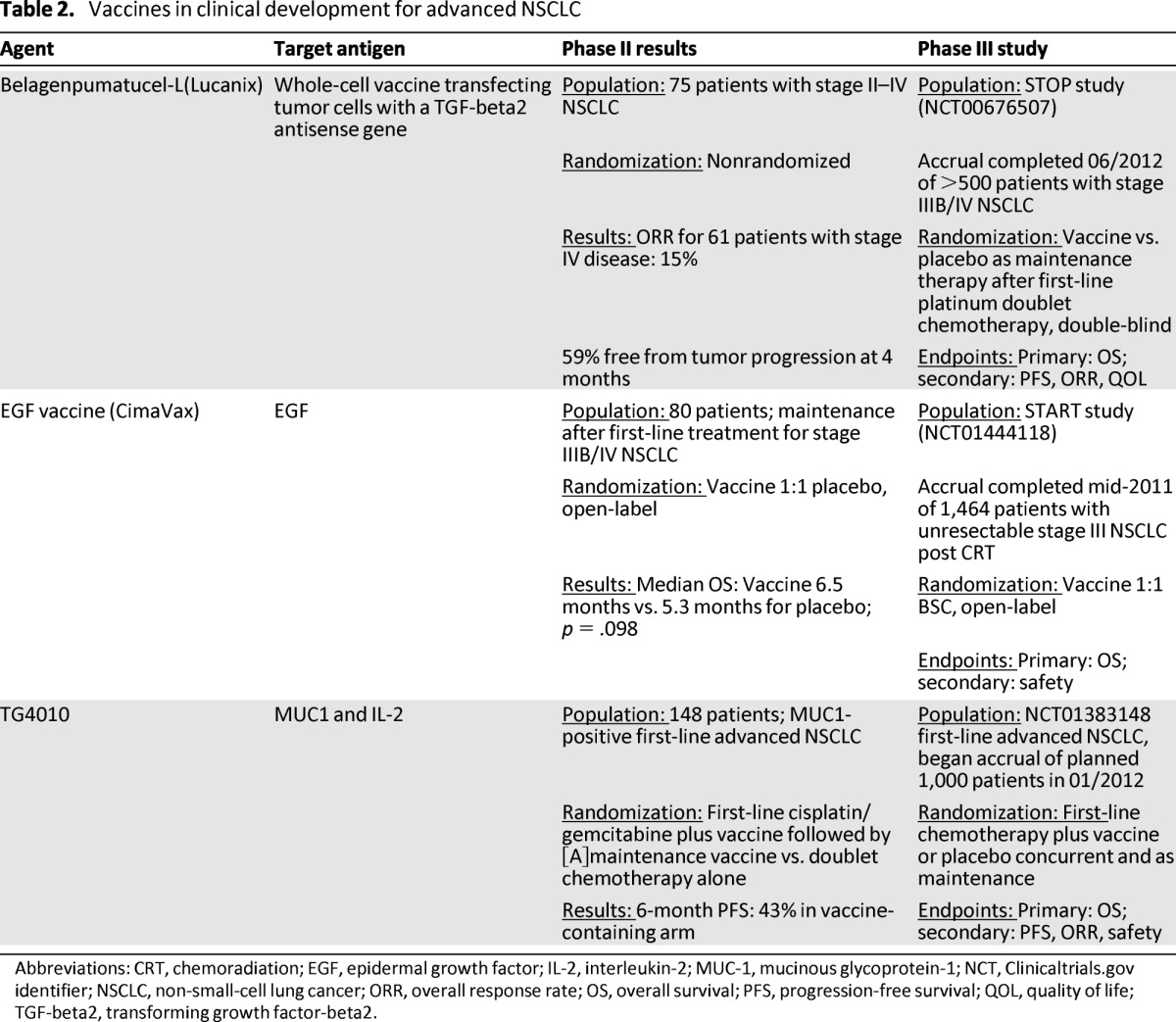

In a phase II dose-variable study, 75 patients with stage II–IV NSCLC received one of three dose levels of belagenpumatucel-L (1.25, 2.5, or 5 x 107 cells/injection) administered as an intradermal injection once monthly or once every other month (Table 2) [7]. No significant difference in serious adverse events was noted between dose cohorts, and the majority of adverse events were attributable to disease activity apart from flu-like symptoms, which were noted in 16% of patients. Among 61 patients with advanced NSCLC (stage IIIB/IV), the partial response rate was 15%, and 59% of all enrolled patients were free from disease progression at four months. Patients who responded to the vaccine had significantly increased blood levels of cytokines including interferon gamma, interleukin-6, and interleukin-4 as well as detectable antibodies to vaccine human leukocyte antigens when compared with nonresponders. In a subsequent phase II study that enrolled 20 patients with stage IV NSCLC, no partial or complete responses were noted. However, 14 of 20 patients had stable disease at four months and no new safety issues were noted [44].

Table 2.

Vaccines in clinical development for advanced NSCLC

Abbreviations: CRT, chemoradiation; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IL-2, interleukin-2; MUC-1, mucinous glycoprotein-1; NCT, Clinicaltrials.gov identifier; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; QOL, quality of life; TGF-beta2, transforming growth factor-beta2.

The phase III STOP trial compared belagenpumatucel-L (2.5 x 107 cells/injection) versus placebo as maintenance therapy after standard platinum doublet chemotherapy for locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC [45]. This study completed enrollment of more than 500 patients with stage IIIA (T3N2 only), IIIB, or IV NSCLC in mid-2012 and has a primary endpoint of OS. Results from this study are awaited.

EGF

The EGF receptor pathway is integral to the growth and metastasis of NSCLC and represents an obvious target for therapeutic interventions, including vaccine-based strategies. The EGF vaccine (CIMAvax EGF) was developed in Cuba and consists of human recombinant EGF combined with a Neisseria meningitidis-derived carrier protein and an immunoadjuvant [46]. EGF vaccination is postulated to stimulate a specific antibody-mediated immune response against EGF, preventing it from binding with its receptor and inhibiting tumor cell growth rather than directly causing cellular toxicity and death [46]. In a phase II study, 80 patients with advanced NSCLC received first-line platinum doublet chemotherapy and were then randomly assigned to BSC or EGF vaccine injections weekly for four weeks and then monthly after an initial single low dose of cyclophosphamide [8]. The primary endpoint of the study was OS. Vaccination was well tolerated, with fewer than 25% of patients experiencing adverse events and no grade 3 or 4 events noted. Anti-EGF antibodies increased to more than four times their baseline level in 51.4% of patients. Patients who received the vaccine had a nonsignificant trend for improved OS compared with those who did not (6.5 months vs. 5.3 months; p = .098) and vaccinated patients in whom antibodies to EGF developed lived significantly longer than patients who had a poor antibody response (11.7 months vs. 3.6 months; p = .0002). Building on these results, an international phase III study has completed enrollment of 579 patients with advanced NSCLC who had stable or responding disease following initial platinum doublet chemotherapy [47]. Based on an exploratory analysis from the phase II study suggesting that younger patients may derive more benefit from EGF vaccination, enrollment on the phase III study was confined to patients aged 20–65 years. Efficacy results from this study are expected in late 2013.

TG4010

TG4010 is a recombinant viral vector consisting of attenuated Ankara virus genetically modified to express MUC1 and interleukin-2 [48]. In a phase II study, TG4010 was administered with first-line cisplatin/vinorelbine chemotherapy to advanced NSCLC patients with tumors expressing MUC1 by immunohistochemistry [48]. The combination demonstrated good tolerance and encouraging preliminary efficacy, with 13 of 37 evaluable patients having an objective response to combined chemotherapy/vaccination. In another large phase IIB study, 148 patients with advanced NSCLC were randomly assigned to first-line cisplatin/gemcitabine chemotherapy alone or in combination with TG4010 vaccine, with a primary endpoint of six-month PFS and a target rate of 40% or higher in the experimental group [9].The combination of vaccine and chemotherapy did not cause any significant increase in serious toxicity, and 43% of patients in the experimental arm were free of progression at six months, thus crossing the predefined boundary for efficacy. Prespecified analysis of the cellular immune response to MUC1 did not show a significant difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients. However, an exploratory analysis suggested that increased levels of natural killer cells might inhibit response to the vaccine. In January 2012, a phase IIB/III study of TG4010 was launched, comparing first-line platinum doublet chemotherapy with TG4010 to chemotherapy alone. The primary endpoint of the phase III portion of this study is OS [49]. Patients enrolled in this study will receive weekly subcutaneous injections of vaccine or placebo during the first six weeks of chemotherapy followed by injections once every three weeks until disease progression [49].

Immune Checkpoint Blockade

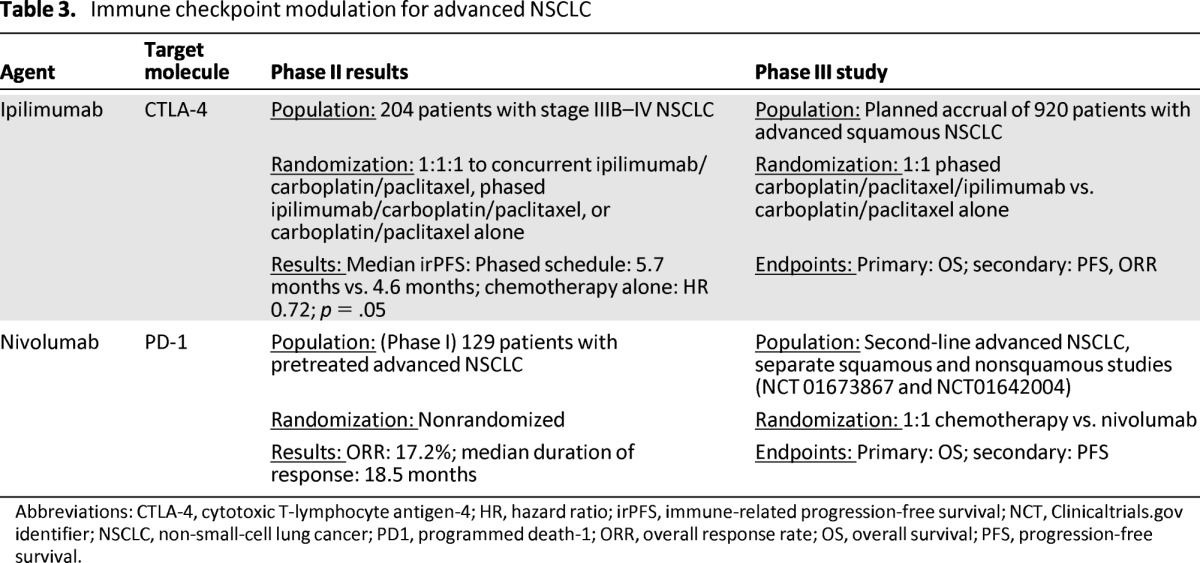

Several checkpoint molecules exist which dampen the T-cell immune response to antigens expressed by tumor cells [50]. Monoclonal antibodies interacting with two of these molecular pathways, PD-1 and CTLA-4, have shown activity in advanced NSCLC (Table 3). Immune checkpoint inhibition is of particular interest because some patients with advanced solid tumors appear to derive unusually prolonged benefits; this has been most clearly demonstrated in metastatic melanoma, where approximately 5%–8% of patients will live many years with stable or responsive disease after anti-CTLA-4 antibody treatment [51, 52].

Table 3.

Immune checkpoint modulation for advanced NSCLC

Abbreviations: CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4; HR, hazard ratio; irPFS, immune-related progression-free survival; NCT, Clinicaltrials.gov identifier; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PD1, programmed death-1; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Immune checkpoint inhibition is of particular interest because some patients with advanced solid tumors appear to derive unusually prolonged benefits; this has been most clearly demonstrated in metastatic melanoma, where approximately 5%–8% of patients will live many years with stable or responsive disease after anti-CTLA-4 antibody treatment.

Anti-CTLA-4

Ipilimumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits CTLA-4, a negative co-regulatory molecule expressed on T cells, thus potentially augmenting antitumor immunity [53]. Extensive investigation of ipilimumab for advanced melanoma ultimately led to regulatory approval when it became the first agent to show a survival advantage in phase III clinical trials [51, 52]. In a large phase II study in lung cancer, 204 patients with advanced NSCLC were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to one of three arms: standard carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy with placebo, concurrent ipilimumab (four doses of ipilimumab plus paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by two doses of placebo plus paclitaxel and carboplatin), or phased ipilimumab (two doses of placebo plus paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by four doses of ipilimumab plus paclitaxel and carboplatin) [10]. Patients with stable disease or a tumor response after four cycles of chemotherapy continued to receive infusions of ipilimumab or placebo every three months until disease progression. The dose of ipilimumab used in this study was higher than that approved for melanoma (10 mg/kg vs. 3 mg/kg). This study was innovative in being the first reported phase II study to adopt immune-related PFS (irPFS) as its primary endpoint. irPFS is defined as the time from random assignment to immune-related progression or death. The use of irPFS as an endpoint for novel immunotherapy trials was initially proposed as a result of observations made in melanoma clinical trials that the pattern of response to immunotherapies differs from the pattern of response seen with traditional cytotoxic agents [54]. With immune checkpoint inhibition, a minority of patients have initially demonstrated progressive disease by traditional Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) followed by a delayed response to immunotherapy and in some cases prolonged survival [55].

Secondary endpoints for the phase II study of ipilimumab in NSCLC included modified World Health Organization response criteria, PFS, OS, and other immune-related response criteria. There was no significant overall difference in grade 3 or 4 toxicity among the three arms of the study. However, grade 3 or 4 events thought to be of immune etiology occurred in 6% of patients in the control arm, 20% of patients in the concurrent chemotherapy/ipilimumab arm, and 15% of patients in the phased ipilimumab arm. Grade 3 or 4 immune-related adverse events included diarrhea, colitis, transaminitis, and pituitary dysfunction, all of which are previously described side effects of CTLA-4 inhibition [56]. From an efficacy standpoint, the phased ipilimumab schedule prolonged irPFS compared with the control regimen of chemotherapy alone (median irPFS phased schedule 5.7 months vs. 4.6 months control; HR 0.72; p = .05), whereas concurrent ipilimumab did not demonstrate a significant difference from chemotherapy alone (5.5 months vs. 4.6 months, HR; 0.82; p = .13). There was no significant difference in OS among the three groups. In a non-preplanned subgroup analysis, the benefit of phased ipilimumab appeared to be more pronounced in patients with squamous tumors (irPFS: HR 0.55; 95% CI 0.27–1.12), leading to the commencement of a phase III study in this cohort [57]. This study will randomly assign 920 patients in a 1:1 ratio to either the phased schedule of ipilimumab beginning after two of a planned six cycles of chemotherapy followed by maintenance ipilimumab or the same schedule of chemotherapy with placebo. The primary endpoint for this international study is OS. The estimated primary completion date is September 2014.

Anti-PD-1 and Anti-PD-L1

The main role of PD-1in normal human physiology is to limit autoimmunity by acting as a co-inhibitory immune checkpoint expressed on the surface of T cells and other immune cells, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [58]. The principle ligands for PD-1 are upregulated in response to inflammation and as an adaptive response to antitumor immunity exhibited by the host. PD-L1, one of two ligands of PD-1, is highly expressed in human tumors and has been associated with a poor prognosis [59].

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a primary method of tumor immune evasion, with upregulation of the pathway leading to immune tolerance and tumor progression [58]. Several agents targeting PD-1 are in clinical development, including nivolumab (BMS-936558), lambrolizumab (MK-3475), MEDI4736, and AMP-224. Promising early data in NSCLC have been reported in separate phase I studies of nivolumab and lambrolizumab.

An initial phase I single dose, dose-escalation study of nivolumab enrolled 39 patients who were heavily pretreated and had advanced solid tumors including NSCLC [60]. Nivolumab was well tolerated, with grade 2 colitis, polyarthritis, and hypothyroidism each occurring in one patient. The maximum tolerated dose was not reached. Among the four patients who experienced clinical benefit was one patient with NSCLC who had a sustained response not reaching RECIST criteria for a partial response. Subsequently, a large phase IB multicenter study of single-agent nivolumab enrolled 296 patients who were heavily pretreated and had advanced NSCLC, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, castration-resistant prostate cancer, or advanced colorectal cancer [11]. Toxicity from nivolumab, including fatigue and diarrhea, was manageable, with grade 3 or 4 toxicities experienced by 14% of patients. Of note, three patients on this early study experienced fatal pneumonitis. Because of this complication, treatment protocols now include the early use of immunosuppression and this appears to mitigate toxicity, as discussed below. Encouraging efficacy signals were seen in renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and most surprisingly, NSCLC, where 16% of patients experienced an objective response and 33% were free from tumor progression at six months [61]. Responses were noted in 9 of 48 patients (18.8%) with squamous NSCLC and 11 of 73 patients (15.1%) with nonsquamous NSCLC, suggesting activity in both histologic subtypes [61]. Long-term data on 129 patients with advanced NSCLC treated with nivolumab were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in 2013; an overall response rate of 17.2% (squamous 16.7%; nonsquamous 17.6%) was reported, with a median duration of response of 18.5 months [62]. Of note, the kinetics of response to anti-PD-1 in NSCLC are consistent with those reported with other immune-based therapeutics such as ipilimumab in melanoma, with most responses being durable (55% of responses ongoing at the time of report) and responses continuing for several patients after discontinuation of therapy. Drug-related adverse events (any grade) occurred in 71% of patients with NSCLC, with grade 3–4 drug-related adverse events reported in 14%. Drug-related pneumonitis occurred in 6% of patients; 2% of these were grade 3–4, and two deaths from pneumonitis occurred in patients with NSCLC. Current suggested management algorithms for patients with suspected grade 2 pneumonitis related to anti-PD-1 involve discontinuation of the drug, prompt systemic steroid therapy, and consideration of empiric antibiotics because of the challenges involved in differentiating infective versus drug-induced pneumonitis [63]. Grade 3–4 pneumonitis requires immediate discontinuation of the drug, early high-dose steroid administration, and consideration of adjunctive immunosuppressant therapy such as infliximab, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide [63]. As with immune-related adverse events caused by anti-CTLA-4, patients may require prolonged tapering of immunosuppression to avoid recurrence of the adverse event. Nivolumab has now entered phase III clinical investigation as a single agent compared with second-line single-agent chemotherapy for advanced squamous and nonsquamous NSCLC [64, 65]. Expression of PD-L1 by immunohistochemical analysis of tumor cells is a possible marker of response to anti-PD-1; however, this has yet to be prospectively validated [11]. Recently reported data using automated immunohistochemical assays suggest that although patients with tumors expressing PD-L1 may be more likely to respond to PD-1/PD-L1-based therapeutics, lack of PD-L1 expression using these assays does not exclude the possibility of benefit from immunomodulators [66, 67]. In reality, it is likely that the mechanisms of response to PD-1 and PD-L1-directed immunomodulators are complex and elucidating markers of response may require an improved understanding of both the host and tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibition. To this end, our group is initiating a pilot neoadjuvant study of nivolumab in resectable non-small cell lung cancer to assess the safety and feasibility of anti-PD-1 in earlier-stage disease and profile in detail the immune system in initial tumor biopsies and in resection specimens after anti-PD-1 treatment.

Lambrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin G4 antibody against PD-1 that has shown preliminary efficacy in a phase I study in advanced refractory solid tumors. Data from patients with NSCLC enrolled in this study were presented in abstract form at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in 2012 [12]. At the time of report, 17 patients had received lambrolizumab at one of three dose levels (1, 3, and 10 mg/kg). Lambrolizumab was generally well tolerated. Grade 2 pneumonitis responsive to steroid therapy occurred in one patient, grade 1/2 pruritis was noted in 4 of 17 patients, and one unconfirmed partial response was reported in a patient with NSCLC.

The anti-PD-L1 antibody, BMS-936559, has also shown preliminary efficacy in a phase I study in which patients with advanced solid tumors (NSCLC, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer) refractory to at least one standard systemic therapy received BMS-936559 as an intravenous infusion on day 1, 15, and 29 of a 42-day cycle for a total of up to 16 cycles [68]. From 49 evaluable patients with NSCLC, the overall response rate was 10% at the time of report, and 31% of patients were free from tumor progression at six months.

Most recently, another PD-L1 antibody, MPDL3280A, has demonstrated good tolerance and promising efficacy in a phase I study that included patients with advanced NSCLC [67]. MPDL3280A is an immunoglobulin G4 antibody that has been engineered to remove its antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function, thus theoretically avoiding the killing of tumor-directed activated T cells. In this study, 52 patients with advanced NSCLC who were heavily pretreated were enrolled with no maximum tolerated dose or dose-limiting toxicities reported up to a dose of 20 mg/kg. In addition, no grade 3–5 pneumonitis was noted in this study. The ORR in the overall cohort was 21% with a 24-week PFS rate of 45%. Studies of MPDL3280A in NSCLC and other solid tumors are ongoing.

Conclusion

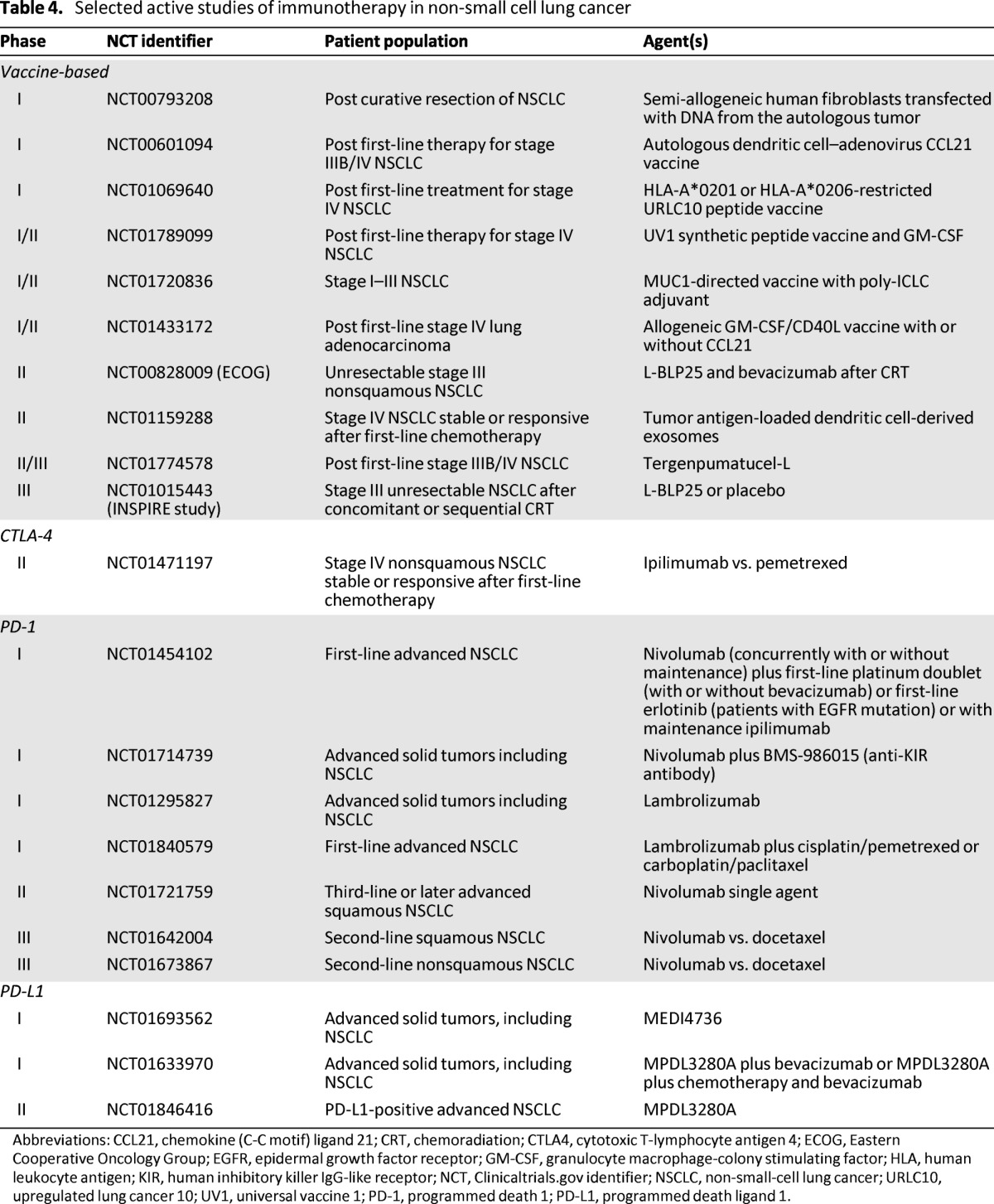

Immunotherapy as a treatment for NSCLC has experienced a welcome renaissance over the past few years. Several large phase III clinical trials of vaccine therapies have completed accrual and detailed results are awaited. Immune checkpoint antibodies including nivolumab and ipilimumab have shown promise in early phase trials and phase III studies are ongoing (Table 4). Significant challenges remain, most importantly the validation of durable biomarkers of response. PD-L1 expression is a candidate biomarker of response to PD-1/PD-L1-directed therapies; however, recently reported data suggest that even patients with tumors lacking PD-L1 expression may derive benefit from these immunomodulators, thus highlighting the need for more detailed profiling of NSCLC immunology, particularly as it pertains to immune modulation. Refinement of response criteria to immune therapeutics will guide clinical investigation and ensure that patients are not taken off therapy prematurely. Important questions remain about the optimal sequence and combination of immune-based therapies and it is hoped the ongoing and planned studies will provide clarity as these therapies move forward to routine use.

Table 4.

Selected active studies of immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer

Abbreviations: CCL21, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21; CRT, chemoradiation; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; KIR, human inhibitory killer IgG-like receptor; NCT, Clinicaltrials.gov identifier; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; URLC10, upregulated lung cancer 10; UV1, universal vaccine 1; PD-1, programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Amer M. Zeidan, Julie R. Brahmer

Provision of study material or patients: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Julie R. Brahmer

Collection and/or assembly of data: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Julie R. Brahmer

Data analysis and interpretation: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Julie R. Brahmer

Manuscript writing: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Amer M. Zeidan, Julie R. Brahmer

Final approval of manuscript: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Amer M. Zeidan, Julie R. Brahmer

Disclosures

Julie R. Brahmer: Bristol-Myers Squibb (C/A); Celgene (C/A); Eli Lilly (C/A); Genentech/Roche (C/A); Merck (C/A); Bristol-Myers Squibb (RF); MedImmune (RF); ArQuele (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:175–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hersh EM, Mavligit GM, Gutterman JU. Immunotherapy as related to lung cancer: A review. Semin Oncol. 1974;1:273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vansteenkiste J, Zielinski M, Linder A, et al. Final results of a multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II study to assess the efficacy of MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy in stage IB/II non-small cell lung cancer. Paper presented at: 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting; June 1–5, 2007; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butts C, Murray N, Maksymiuk A, et al. Randomized phase IIB trial of BLP25 liposome vaccine in stage IIIB and IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6674–6681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemunaitis J, Dillman RO, Schwarzenberger PO, et al. Phase II study of belagenpumatucel-L, a transforming growth factor beta-2 antisense gene-modified allogeneic tumor cell vaccine in non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4721–4730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neninger Vinageras E, de la Torre A, Osorio Rodríguez M, et al. Phase II randomized controlled trial of an epidermal growth factor vaccine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1452–1458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quoix E, Ramlau R, Westeel V, et al. Therapeutic vaccination with TG4010 and first-line chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A controlled phase 2B trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, et al. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2046–2054. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patnaik A, Kang SP, Tolcher AW, et al. Phase I study of MK-3475 (anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl) doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2607. abstr 2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: A national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankaran V, Ikeda H, Bruce AT, et al. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 2001;410:1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/35074122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD, et al. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:235–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalialis LV, Drzewiecki KT, Klyver H. Spontaneous regression of metastases from melanoma: Review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:275–282. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32832eabd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shablak A, Sikand K, Shanks JH, et al. High-dose interleukin-2 can produce a high rate of response and durable remissions in appropriately selected patients with metastatic renal cancer. J Immunother. 2011;34:107–112. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fb659f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shibli KI, Donnem T, Al-Saad S, et al. Prognostic effect of epithelial and stromal lymphocyte infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5220–5227. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimizu K, Nakata M, Hirami Y, et al. Tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are correlated with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and are associated with recurrence in resected non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:585–590. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d60fd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YC, Sung WW, Wu TC, et al. Interleukin-10 haplotype may predict survival and relapse in resected non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung WW, Wang YC, Cheng YW, et al. A polymorphic -844T/C in FasL promoter predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5991–5999. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terme M, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, et al. Modulation of immunity by antiangiogenic molecules in cancer. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012:492920. doi: 10.1155/2012/492920. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsh V, Paz-Ares L, Boyer M, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel/carboplatin with or without PF-3512676 (toll-like receptor 9 agonist) as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2667–2674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manegold C, van Zandwijk N, Szczesna A, et al. A phase III randomized study of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without PF-3512676 (TLR9 agonist) as first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:72–77. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh PM, Vaid A, Advani SH, Digumarti R, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study of single-agent oral talactoferrin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer that progressed after chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4129–4136. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Digumarti R, Wang Y, Raman G, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study of oral talactoferrin in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1098–1103. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182156250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramalingam SS, Crawford J, Chang A, et al. FORTIS-M, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral talactoferrin alfa with best supportive care in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer following two or more prior regimens- by the FORTIS-M Study Group. Paper presented at: European Society of Medical Oncology Annual Meeting; September 26, 2012; Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gure AO, Chua R, Williamson B, et al. Cancer-testis genes are coordinately expressed and are markers of poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Nov 15;11(22):8055–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vansteenkiste J. Novel approaches in immunotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Paper presented at: American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting; April 5, 2013; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vansteenkiste J, Zielinski M, Linder A, et al. Phase II randomized study of MAGE-A3 immunotherapy as adjuvant therapy in stage IB/II non-small-cell lung cancer: 44 month follow-up, humeral and cellular immune response data. Paper presented at: IASLC World Lung Cancer Conference; September 2, 2007; Seoul, South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vansteenkiste JF, Zielinski M, Dahabreh IJ, et al. Association of gene expression signature and clinical efficacy of MAGE-A3 antigen-specific cancer immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy in resected stage IB/II non-small cell lung cancer. Paper presented at: ASCO Annual Meeting; May 30-June 3, 2008; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clinical Trials. gov. GSK1572932A antigen-specific cancer immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials. gov/ct2/results?term=NCT00480025&Search=Search.

- 34.Tyagi P, Mirakhur B. MAGRIT. The largest-ever phase III lung cancer trial aims to establish a novel tumor-specific approach to therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:371–374. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlad AM, Kettel JC, Alajez NM, et al. MUC1 immunobiology: From discovery to clinical applications. Adv Immunol. 2004;82:249–293. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)82006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decoster L, Wauters I, Vansteenkiste JF. Vaccination therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: Review of agents in phase III development. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1387–1393. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butts C, Maksymiuk A, Goss G, et al. Updated survival analysis in patients with stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer receiving BLP25 liposome vaccine (L-BLP25): Phase IIB randomized, multicenter, open-label trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1337–1342. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical Trials.gov. Cancer vaccine study for unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT00409188&Search=Search.

- 39.Butts CA, Socinski MA, Mitchell P, et al. START: A phase III study of L-BLP25 cancer immunotherapy for unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) abstr 7500. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clinical Trials.gov. Cancer vaccine study for stage III, unresectable, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the Asian population. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01015443&Search=Search.

- 41.Clinical Trials.gov. BLP25 liposome vaccine and bevacizumab after chemotherapy and radiation therapy in treating patients with newly diagnosed stage IIIA or stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer that cannot be removed by surgery. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT00828009&Search=Search.

- 42.Bierie B, Moses HL. TGF-beta and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malkoski SP, Haeger SM, Cleaver TG, et al. Loss of transforming growth factor beta type II receptor increases aggressive tumor behavior and reduces survival in lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2173–2183. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nemunaitis J, Nemunaitis M, Senzer N, et al. Phase II trial of belagenpumatucel-L, a TGF-beta2 antisense gene modified allogeneic tumor vaccine in advanced non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:620–624. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clinical Trials.gov. Phase III Lucanix™ vaccine therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) following front-line chemotherapy. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00676507?term=NCT00676507&rank=1.

- 46.Gonzalez Marinello GM, Santos ES, Raez LE. Epidermal growth factor vaccine in non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:439–445. doi: 10.1586/era.12.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clinical Trials.gov. A randomized trial to study the safety and efficacy of EGF cancer vaccination in late-stage (IIIB/IV) non-small cell lung cancer patients. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01444118&Search=Search.

- 48.Ramlau R, Quoix E, Rolski J, et al. A phase II study of Tg4010 (Mva-Muc1-Il2) in association with chemotherapy in patients with stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:735–744. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817c6b4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clinical Trials.gov. Phase IIB/III Of TG4010 immunotherapy In patients With stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01383148&Search=Search.

- 50.Drake CG, Jaffee E, Pardoll DM. Mechanisms of immune evasion by tumors. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:51–81. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pentcheva-Hoang T, Corse E, Allison JP. Negative regulators of T-cell activation: Potential targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer, autoimmune disease, and persistent infections. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:67–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoos A, Eggermont AM, Janetzki S, et al. Improved endpoints for cancer immunotherapy trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1388–1397. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pennock GK, Waterfield W, Wolchok JD. Patient responses to ipilimumab, a novel immunopotentiator for metastatic melanoma: How different are these from conventional treatment responses? Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:606–611. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318209cda9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Di Giacomo AM, Biagioli M, Maio M. The emerging toxicity profiles of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies across clinical indications. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:499–507. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clinical Trials.gov. Trial in squamous non small cell lung cancer subjects comparing ipilimumab plus paclitaxel and carboplatin versus placebo plus paclitaxel and carboplatin. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01285609&Search=Search.

- 58.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Targeting the PD-1/B7–H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7–H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: Safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Topalian SL, Brahmer JR, Hodi FS, et al. Anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) (BMS-936558/MDX-1106/ONO in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors: Clinical activity, safety, and molecular markers. Paper presented at the 2012 European Society for Medical Oncology Annual Meeting; September 28,2012; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brahmer JR, Horn L, Antonia SJ, et al. Survival and long-term follow-up of the phase I trial of nivolumab in patients with previously treated ad-vanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) abstr 8030. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Topalian SL, Sznol M, Brahmer JR, et al. Nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538) in patients with advanced solid tumors: Survival and long-term safety in a phase I trial. Presented at: 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting; May 31-June 4 2013; Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clinical Trials.gov. Study of BMS-936558 compared to docetaxel in previously treated advanced or metastatic non-squamous NSCLC. [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01673867&Search=Search.

- 65.Clinical Trials.gov. Study of BMS-936558 compared to docetaxel in previously treated advanced or metastatic squamous cell non-small cell lung can-cer (NSCLC) [Accessed September 11, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01642004&Search=Search.

- 66.Grosso J, Horak CE, Inzunza D, et al. Association of tumor PD-L1 expression and immune biomarkers with clinical activity in patients with advanced solid tumors treated with nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) abstr 3016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spigel DR, Gettinger SN, Horn L, et al. Clinical activity, safety and biomarkers of MPDL3280A, an engineered PD-L1 antibody in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) abstr 8008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]