Chemotherapy for platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer is motivated by the hope of benefit. Trait hope and expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy appear to be distinct and independent of quality of life and depression. Hope did not appear to affect perceived efficacy of chemotherapy in alleviating symptoms, but women whose expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy was not fulfilled were more likely to have scores indicative of depression.

Keywords: Recurrent ovarian cancer, Symptoms, Hope, Symptom benefit, Chemotherapy

Learning Objectives

Explain the connection between depression and unrealistic expectations of the benefits of palliative therapy.

Distinguish the trait of general hopefulness from hope for a specific favorable outcome.

Abstract

Purpose.

Chemotherapy for platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer is motivated by the hope of benefit. We sought to determine the relationships between: (a) trait hope, expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy, and anxiety and depression; (b) hope and perceived efficacy of chemotherapy; and (c) unfulfilled hope (where expectations for benefit are not fulfilled) and depression.

Methods.

Adult patients enrolled within stage 1 of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Symptom Benefit Study were included.

Patient.

Reported outcomes were collected from 126 women with predominantly platinum-resistant ovarian cancer at baseline, prior to the first four treatment cycles (12–16 weeks), and four weeks after completing chemotherapy or at disease progression, whichever came first. Associations were assessed with Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r) and odds ratio.

Results.

Trait hope and expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy were weakly correlated with each other (r = 0.25). Trait hope, but not expectation of symptom benefit, was negatively correlated with anxiety (r = −0.43) and depression (r = −0.50). The smaller the discrepancy between perceived and expected symptom benefit, the less likely the patient was to have scores indicative of depression (odds ratio: 0.68; 95% confidence interval: 0.49–0.96; p = .026).

Conclusion.

Trait hope and expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy appear to be distinct and independent of the aspects of quality of life and scores for depression. Hope did not appear to affect perceived efficacy of chemotherapy in alleviating symptoms, but women whose expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy was not fulfilled were more likely to have scores indicative of depression. It may be preferable to encourage hope toward achievable goals rather than toward benefits from chemotherapy.

Implications for Practice:

Many women with platinum resistant ovarian cancer decide to continue chemotherapy out of hope, even if their prognosis is very poor. They hope the chemotherapy will reduce the size of the cancer, give them more time, or reduce their symptoms. While most clinicians would agree that hope is a positive attribute, this study showed that if women's hopes were not fulfilled, they were more likely to become depressed. This suggests that clinicians should be careful to communicate in a way that encourages realistic hope, targeted toward achievable goals, as this may protect women from depression.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death in women with gynecological malignancies in the Western world. Most women present with advanced disease and following surgery receive platinum-based chemotherapy. Although many women initially respond to treatment, the majority will have relapse within 12 to 18 months [1]. Patients who have relapse within six months of receiving, or during, platinum-based chemotherapy (platinum-resistant/refractory disease) have a particularly poor prognosis, with a median survival ranging from three to nine months [2–6]. These women are usually offered second- or third-line chemotherapy with the aims of palliation and improving quality of life, but with an uncertain impact on overall survival.

There are limited data on the actual impact of palliative chemotherapy on symptoms or quality of life. In a prospective study of 27 women with recurrent ovarian cancer offered second- or third-line chemotherapy, only 7 had objective evidence of symptom improvement [7].

Further, women's expectations of therapy appear to be at odds with palliative aims. In the above study, despite having been told that the goal of chemotherapy was palliative, 65% of women expected chemotherapy would make them live longer and 42% thought it would cure them. This discrepancy has been reported in other advanced cancers [8]. In another study of 122 women with ovarian cancer [8], approximately two thirds of women in whom disease had relapsed ranked tumor shrinkage as the most important goal of treatment during repeated chemotherapy, with <8% rating symptom relief as the most important aim of treatment. Discordance between doctors' treatment intent and patients' beliefs about cure increased from 24% at first-line to 83% by fourth-line chemotherapy. Many women, although acknowledging that their disease is incurable, seemingly choose to have chemotherapy as an antidote to hopelessness, to feel they were doing something, and had done everything possible to prolong life [9, 10].

Some health professionals feel that maintenance of hope is a medically worthwhile outcome [9, 10], providing meaning and direction [11–13] and improved coping and quality of life [12, 14–17]. However, it could also be argued that giving women medically futile treatment purely to maintain hope is questionable. If patients' hopes are raised and then not fulfilled, this false hope may increase the risk for depression, and side effects can further reduce well-being.

Despite the common perception that hope is important, there is a lack of clarity in how the term is defined and measured [18]. Some measures, such as the Herth Hope Index [19], portray hope as a general, multidimensional trait (trait hope). In contrast, others focus on a specific element of hope, such as hope for or expectation of a particular outcome (for example, symptom benefit from chemotherapy) [20, 21]. The degree to which hope is distinct from psychological morbidity (anxiety and depression) is not clear. Further research is needed to better understand the role of hope in maintaining well-being [22, 23]. In this study, we explored associations among hope, indices of well-being, and perceived symptom benefits of chemotherapy. We explored four hypotheses in our population, as described below.

Our first hypothesis was that trait hope and the expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy were separate concepts, and would be distinct from psychological well-being and quality of life. Thus, at baseline, trait hope as measured by the Herth Hope Index would be moderately but not strongly correlated with expectation of symptom benefit, and each of these would correlate moderately but not strongly with anxiety, depression, and quality of life.

Our second hypothesis was that trait hope and expectation of symptom benefit at baseline would be associated with perceived benefit from chemotherapy and improvement in self-reported symptoms (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Ovarian [FACT–O] Symptom Index [FOSI]) at follow-up after adjusting for anxiety and depression.

Our third hypothesis was that raised hope, if not fulfilled, would leave patients vulnerable to depression. Thus, disparity between expectation of symptom benefit and perceived symptom benefit from chemotherapy would be associated with increased depression (depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) at follow-up.

Our final hypothesis was that trait hope would modify the impact of a disparity between expectation of symptom benefit and perceived benefit on depression.

Methods

This substudy was part of a larger study of symptom benefit in patients with platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer (stage 1 of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Symptom Benefit Study). This study sought to determine the aspects of health-related quality of life rated least tolerable by patients and patients' most common symptoms. All patients were recruited from centers in Australia and Canada, were ≥18 years of age, and had been diagnosed with epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancers. They all had recurrent cancer and progressive disease (based on CA125, radiological, or clinical criteria). Patients with platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer were eligible (the vast majority of the sample), as were those with potentially platinum-sensitive disease if they were receiving their third or greater line of treatment. All patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0–3, a life expectancy of three months or longer, and had to be able to complete questionnaires independently. Choice of chemotherapy was at the discretion of the treating physician and had to begin within two weeks of the patient's registration. No minimum threshold was set for symptom frequency or severity. Data were collected at baseline, prior to every treatment cycle for four treatment cycles (12–16 weeks), and one month after completion of treatment or at disease progression, whichever came first.

Study Design

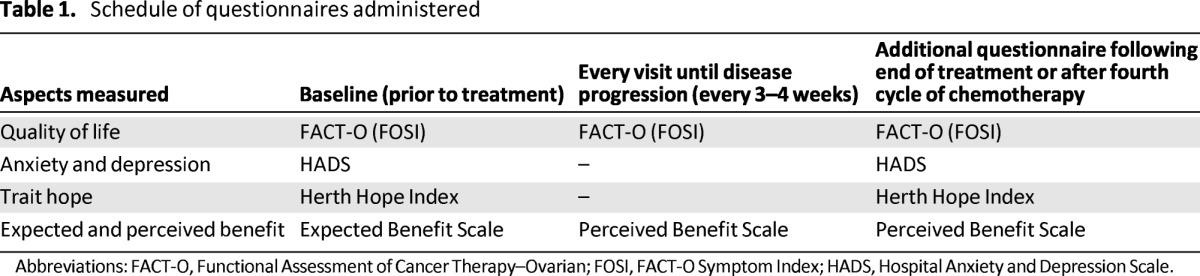

The study had a longitudinal design, with patient- and clinician- completed measures. The schedule for patient-reported outcome measures is shown in Table 1. The questionnaires of relevance to this analysis are included:

Table 1.

Schedule of questionnaires administered

Abbreviations: FACT-O, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian; FOSI, FACT-O Symptom Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

The Herth Hope Index measures the degree to which a patient feels hope and a sense of meaning in her life. The scale has three subscales: temporality and future, positive readiness and expectancy, and interconnectedness. High scores on the measure indicate greater hope [19].

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is comprised of 14 items in two subscales independently measuring anxiety and depression [24]. Subscale scores of 11 or more have been determined to be consistent with clinical anxiety or depression, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety and depression [25].

Expectation of symptom benefit and perceived benefit were measured at baseline and before starting chemotherapy. Patients were asked, “How much do you expect your symptoms to improve with chemotherapy?” Women were asked to rate their expectations using a numeric rating scale, with 0 indicating no expectation of improvement and 10 indicating complete improvement (expected benefit). At follow-up visits after starting chemotherapy and before objective assessment of response, patients were asked, “How much have your symptoms improved with chemotherapy?” using the same scale (perceived benefit). If patients indicated an improvement in symptom control, they completed one item on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from not at all to very much so) asking whether their symptom improvement was enough to affect their overall quality of life.

The FOSI is comprised of the FACT–General, a 28-item self-reported measure that assesses four dimensions of well-being: physical, functional, social/family, and emotional well-being, plus an ovarian cancer-specific subscale [26]. The FOSI is a very brief (eight-item) index derived from the FACT-O to measure symptom response to treatment for ovarian cancer. High scores on FACT-O and FOSI indicate worse quality of life.

Statistical Methods

Data were expressed as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables and as means plus or minus standard deviation or medians (interquartile range) for normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively. The independent samples t test was used to test for a difference in two group means. The FACT-O, FACT-General, and FOSI scores were linearly transformed to a scale from 0 to 100.

Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to examine the strength and direction of linear relationships between patient-reported measurements (hypothesis 1). Consistent with Cohen, correlations from 0.10–0.29 were considered weak, from 0.30–0.49 were considered moderate, and 0.50 or more was considered to be strong [27].

To assess improvement or deterioration in physical well-being, two methods were used: the change in FOSI score and the rating of perceived benefit. An increase in FOSI score of at least 10 points (10% of total scale, approximately half a standard deviation) was classified as a significant improvement [28]. A perceived benefit rating of 6 or more was classified as significant perceived improvement, with this threshold representing scores of more than 10% above the median. Patients were then categorized as having improved physical well-being or not and as having perceived benefit or not. Relationships between trait hope, expectation of symptom benefit at baseline, and improvement in physical well-being or perceived benefit at the end of treatment (hypothesis 2) were assessed using logistic regression. Analyses with perceived benefit as the outcome were adjusted for anxiety and depression. However, adjustment was not possible in analyses predicting improved physical well-being because of the small number of women experiencing improved physical well-being [29].

In the subgroup of patients without scores indicative of depression at baseline, the disparity between expectation of symptom benefit and perceived benefit was determined by subtracting scores for perceived benefit from hope for symptom benefit. Logistic regression was then performed to assess the relationship between that disparity and development of scores indicative of depression (hypothesis 3).

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com). Two-sided p values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics and Symptom Complex at Baseline

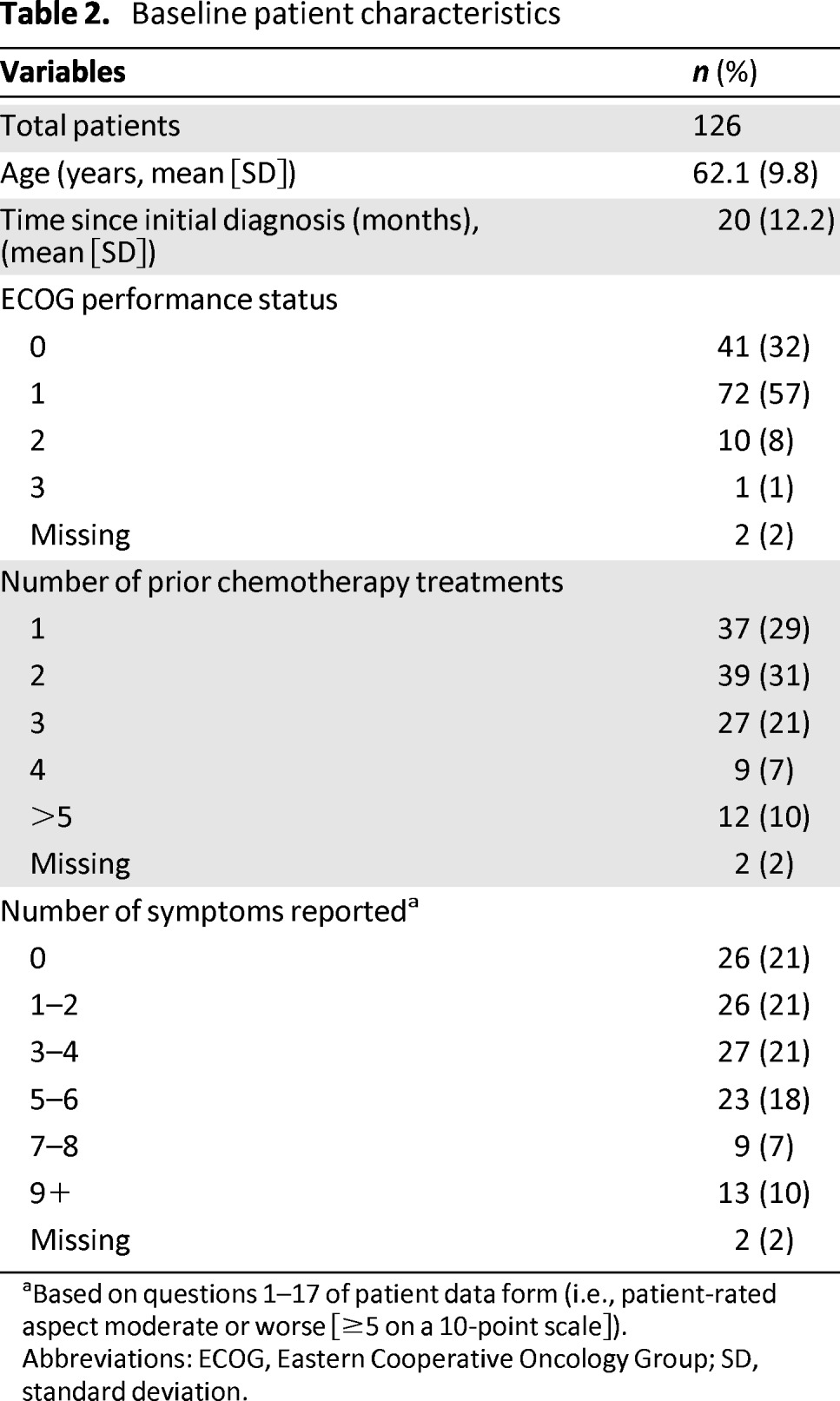

A total of 126 patients were recruited to the study, and 123 had at least one cycle of chemotherapy. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. Mean age was 62 years (range 30–89 years). The majority of patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, with 32% having a performance status of 0. Most patients had platinum-resistant ovarian cancer and had received more than two lines of prior chemotherapy; 38% had received three or more lines of chemotherapy. At least one symptom at moderate or severe levels was reported by 79% of patients based on the patient data form [30].

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics

aBased on questions 1–17 of patient data form (i.e., patient-rated aspect moderate or worse [≥5 on a 10-point scale]).

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; SD, standard deviation.

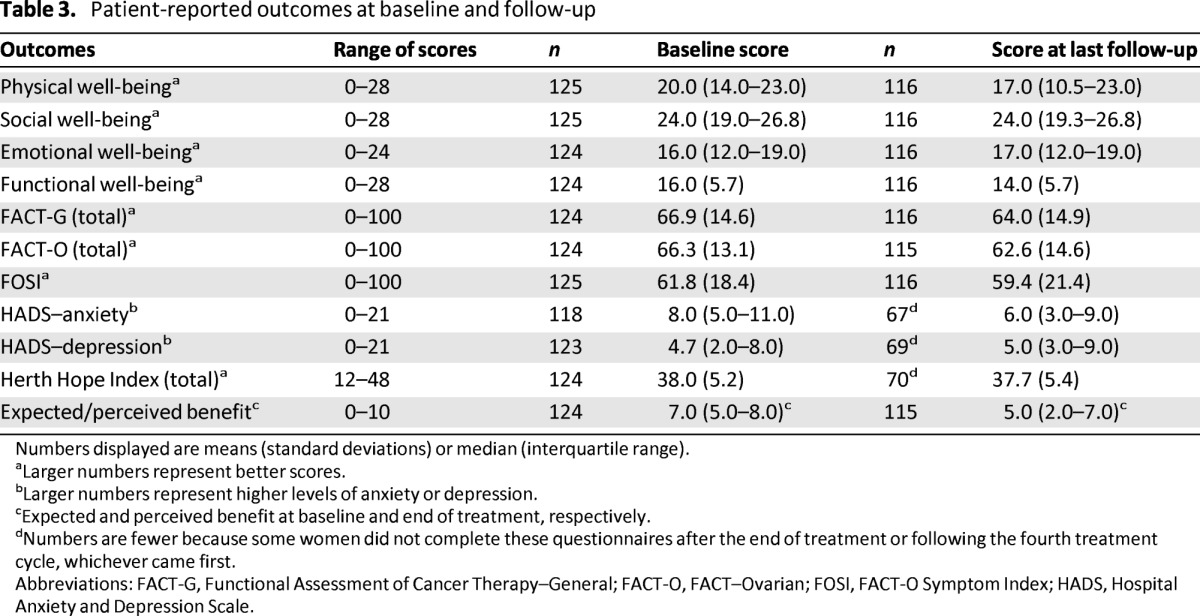

Hope, Depression, Anxiety, and Quality of Life

Hope, depression, anxiety, and quality of life scores at baseline and at the last follow-up assessment are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Patient-reported outcomes at baseline and follow-up

Numbers displayed are means (standard deviations) or median (interquartile range).

aLarger numbers represent better scores.

bLarger numbers represent higher levels of anxiety or depression.

cExpected and perceived benefit at baseline and end of treatment, respectively.

dNumbers are fewer because some women did not complete these questionnaires after the end of treatment or following the fourth treatment cycle, whichever came first.

Abbreviations: FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FACT-O, FACT–Ovarian; FOSI, FACT-O Symptom Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Expectation of Symptom Benefit and Perceived Benefit From Chemotherapy

Most patients expected that their symptoms would improve with treatment; 98% (n = 121) expected some improvement (expected benefit score ≥1), 73% (n = 91) expected a significant improvement (expected benefit score ≥6), and 24% of patients (n = 30) hoped that their symptoms would resolve completely or almost completely (expected benefit score 9 or 10). When asked at their last assessment how much their symptoms had improved, only one patient (1%) reported complete resolution of her symptoms, but at least 38% of patients reported that their symptoms had improved significantly (perceived benefit score of 6 or more).

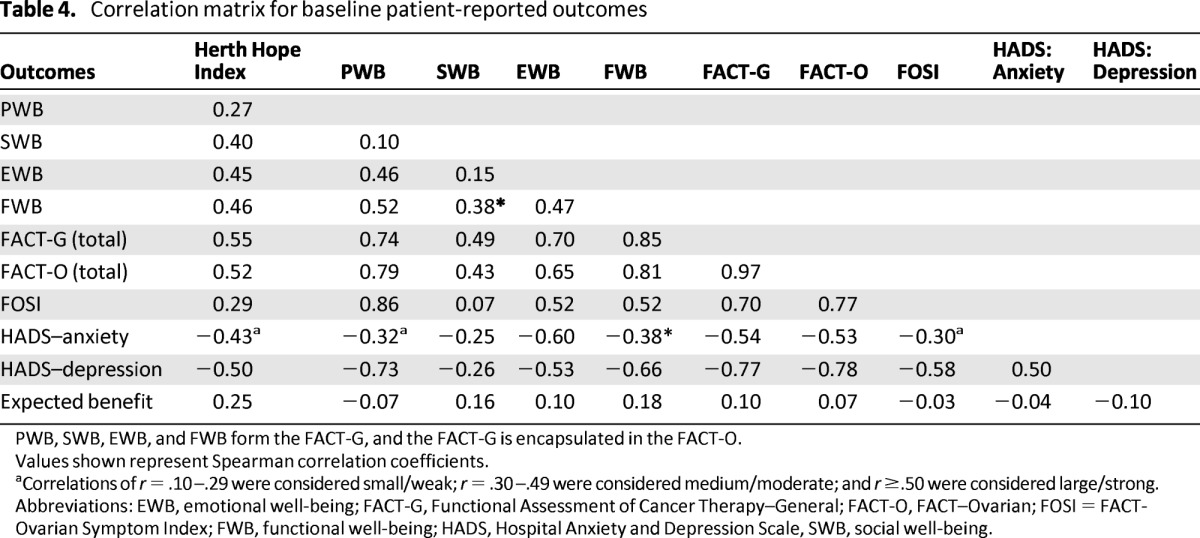

Correlation With Hope at Baseline

There was a weak correlation between trait hope and expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy (0.25), suggesting that they are related but distinct constructs (Table 4). Correlations between trait hope and measures of psychological well-being and quality of life were moderate: −0.43 with anxiety, −0.5 with depression, and 0.45 with emotional well-being on the FACT-O. However, there were no important correlations between expectation of symptom benefit and measures of psychological well-being or quality of life (Table 4). Thus, our first hypothesis was partly supported.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for baseline patient-reported outcomes

PWB, SWB, EWB, and FWB form the FACT-G, and the FACT-G is encapsulated in the FACT-O.

Values shown represent Spearman correlation coefficients.

aCorrelations of r = .10–.29 were considered small/weak; r = .30–.49 were considered medium/moderate; and r ≥.50 were considered large/strong.

Abbreviations: EWB, emotional well-being; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FACT-O, FACT–Ovarian; FOSI = FACT-Ovarian Symptom Index; FWB, functional well-being; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SWB, social well-being.

Impact of Baseline Hope and Expectation of Symptom Benefit on Perceived Benefit and Reported Improvement in Symptoms at Follow-Up

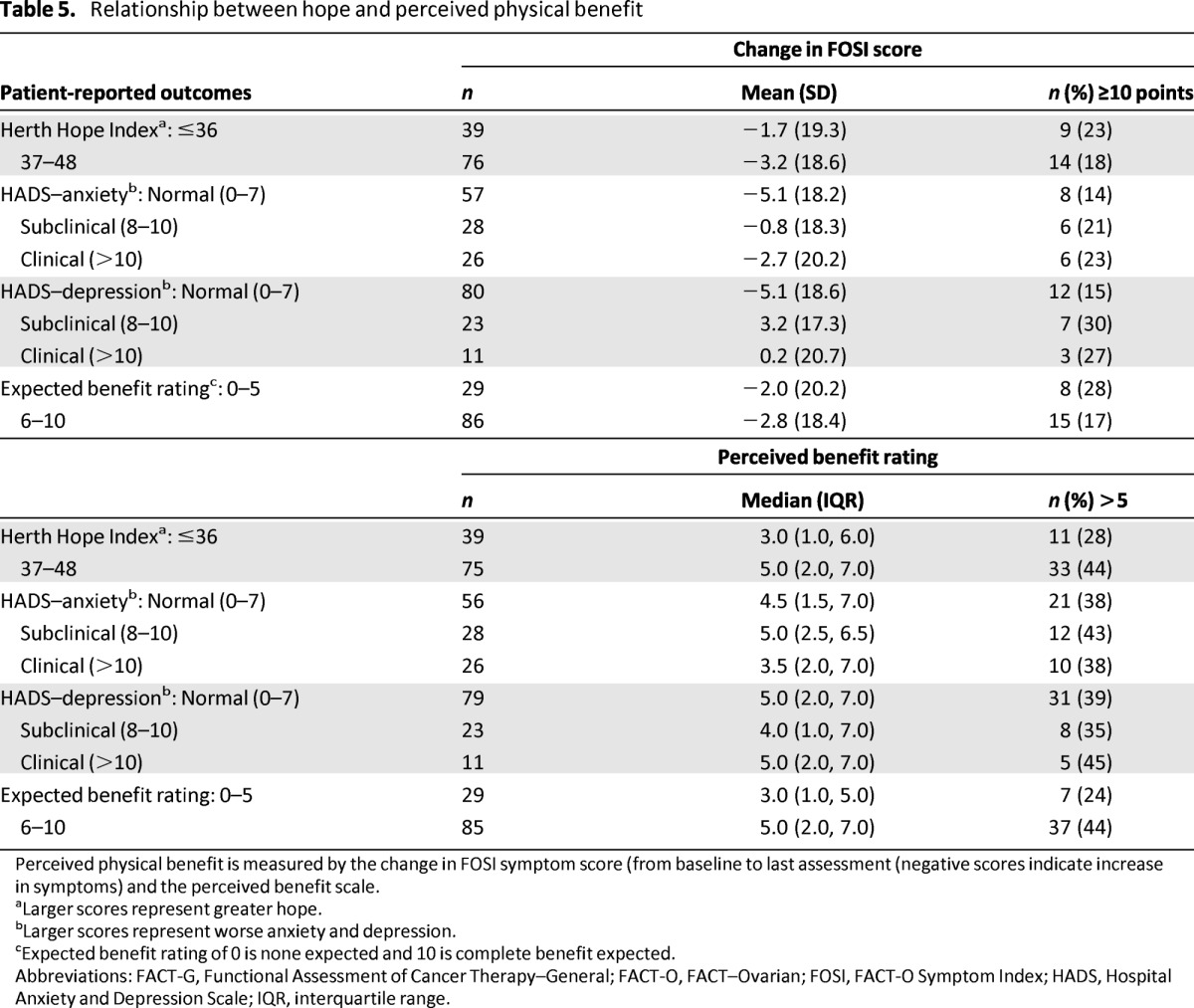

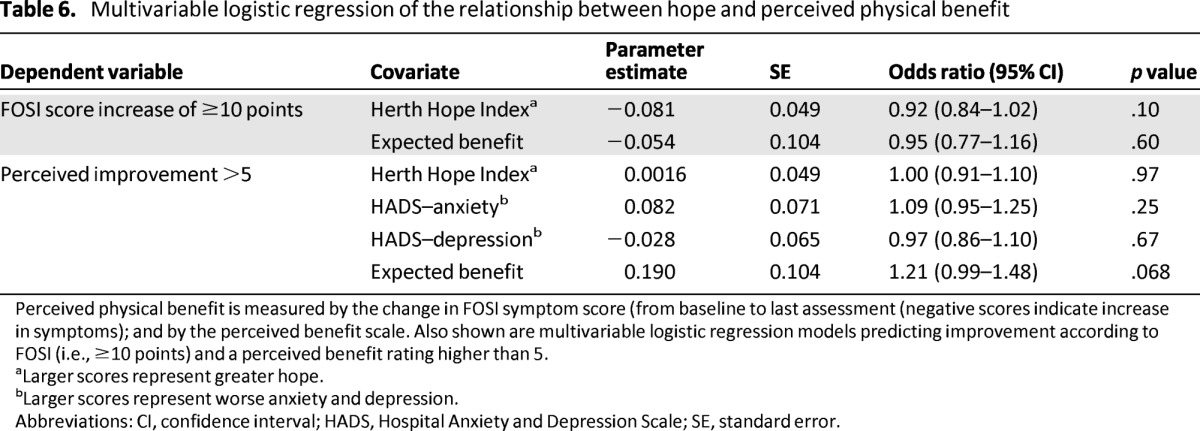

Contrary to hypothesis two, trait hope was not significantly associated with reported improvement in symptoms at follow-up based on either a 10-point increase in the FOSI symptom score, or on a perceived benefit rating greater than 5 (Table 5). Of those women who completed at least one on-treatment questionnaire, 44 (38%) reported a perceived benefit score >5 and 23 (20%) reported an FOSI score that increased by at least 10 points (Table 6). Expectation of symptom benefit was also not associated with symptom improvement based on FOSI.

Table 5.

Relationship between hope and perceived physical benefit

Perceived physical benefit is measured by the change in FOSI symptom score (from baseline to last assessment (negative scores indicate increase in symptoms) and the perceived benefit scale.

aLarger scores represent greater hope.

bLarger scores represent worse anxiety and depression.

cExpected benefit rating of 0 is none expected and 10 is complete benefit expected.

Abbreviations: FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FACT-O, FACT–Ovarian; FOSI, FACT-O Symptom Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 6.

Multivariable logistic regression of the relationship between hope and perceived physical benefit

Perceived physical benefit is measured by the change in FOSI symptom score (from baseline to last assessment (negative scores indicate increase in symptoms); and by the perceived benefit scale. Also shown are multivariable logistic regression models predicting improvement according to FOSI (i.e., ≥10 points) and a perceived benefit rating higher than 5.

aLarger scores represent greater hope.

bLarger scores represent worse anxiety and depression.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SE, standard error.

In unadjusted analysis, expectation of symptom benefit was associated with a higher likelihood of a perceived benefit rating greater than 5 (odds ratio [OR]: 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03–1.52; p = .022); however, after adjustment for anxiety and depression, the effect was attenuated and no longer significant (Table 6).

Impact of Disparity Between Expectation of Symptom Benefit and Perceived Benefit on Development of Depression

Fourteen women had scores indicative of clinical depression at baseline. Of the 111 women without scores indicative of depression at baseline, 61 completed baseline and end-of-treatment (or last follow-up) ratings of depression, expectation of symptom benefit, and perceived benefit. Of these 61 women, 39 reported a perceived benefit less than their expected symptomatic benefit at baseline and were included in the following analysis to test hypothesis three.

As hypothesized, the difference between expectation of symptom benefit and perceived benefit was significantly associated with follow-up scores indicative of depression, and the greater the discrepancy between perceived benefit and expected symptom benefit, the greater the likelihood of a follow-up score indicative of depression (OR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.49–0.96; p = .026). The mean difference between expectation of symptom benefit and perceived benefit ratings among the six patients with scores indicative of depression was −6.8 (95% CI: −9.6 to −4.1) compared with −3.8 (95% CI: −4.7 to −2.8) for the 33 patients who did not have scores indicative of depression (difference in means test: p = .012). Thus, hypothesis three was supported, although results should be interpreted cautiously given the small number of events.

Role of Trait Hope in Mitigating the Impact of Dashed Expectations

Of the 39 evaluable patients who did not perceive a benefit from chemotherapy, 6 had scores indicative of clinical depression at last follow-up. This number of events was insufficient to test for effect modification by levels of trait hope at baseline (hypothesis 4).

Discussion

Our results support the distinction between general trait hope and specific expectation of symptom benefit from chemotherapy in women receiving palliative chemotherapy for platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer. Both hope constructs were independent of aspects of psychological well-being and quality of life. Contrary to our hypotheses, patients' expectations at the beginning of treatment did not affect their perception of benefit from treatment. Importantly, if there was a large discrepancy between expectations of symptom benefit and experienced benefit, women were more likely to have scores indicative of depression. This study lacked sufficient power to explore whether trait hope might mitigate the impact of such a discrepancy. These results suggest that it might be helpful to assess women's expectations for benefit from chemotherapy in this setting. Clinicians need to balance hope giving with a realistic appraisal of likely outcomes.

Strategies for identifying and addressing unrealistic expectations in patients with advanced cancer have been proposed. The inclusion of one negative or pessimistic statement in discussions about the future may limit overly optimistic expectations [31], and the use of decision aids describing average treatment outcomes [32] or various scenarios (best, worst, or typical cases) for prognosis [33] have been shown to be acceptable to patients [34]. The provision of honest information did not dampen hope in one study [32], suggesting honest and realistic information sensitively presented may be most effective at increasing patients' understanding of realistic prognosis and potential benefits from treatment while maintaining hope.

The maintenance of hope is considered by many to be an important goal of palliative chemotherapy for recurrent cancer [35, 36]. Hopefulness may be protective of overall psychological well-being even in the face of a terminal diagnosis. We found that trait hope was moderately correlated with psychological well-being and inversely correlated with anxiety and depression before starting palliative chemotherapy.

Improvement in symptoms and overall quality of life is an important goal of treatment in recurrent ovarian cancer, and a large proportion of women in our study reported that they hoped to benefit substantially from chemotherapy (n = 91, 73%). The dilemma for many clinicians is how to provide a balance between realistic and truthful information regarding the likelihood of symptom benefit from palliative chemotherapy while, at the same time, maintaining appropriate levels of hope [21]. The concern that false or unrealistic hope may ultimately prove to be disadvantageous for the patient is not unwarranted. Expectations that are unrealistically positive, for example maintaining a belief of cure in the terminal stages of an illness, can result in a lack of preparation for death that can lead to increased distress for patients and caregivers and exposure to avoidable futile interventions [37–40]. In our study, patients with the greatest disparity between the symptom improvement they expected versus the improvement achieved, were most likely to have scores indicative of depression. While acknowledging that hope for and expectation of benefit are closely related although not identical evaluations, this suggests that encouraging unrealistic hopes for symptom benefit may be harmful.

It is unclear whether trait hope modifies the risk for depression when unrealistic expectations of symptom benefit are unfulfilled. The current study was underpowered to answer this question. If this were so, it might indicate a potential protector against the disappointment of unrealized expectations, but one that is less amenable to intervention.

The nature of hope for, or expectation of, treatment benefit may change, with different goals along the course of the treatment trajectory [41]. It may therefore be appropriate to encourage patients to direct hope and expectation toward attainable goals that are meaningful for the individual patient [42–44]. Appropriate levels of hope are hard to define and characterize, although misguided hope is often easier to recognize [45]. The challenge for clinicians remains how to help individuals frame a difficult situation in an appropriately hopeful and helpful light.

Conclusions

This study suggests that a smaller disparity between expectations of benefit from chemotherapy may be associated with a lower risk for scores indicative of clinical levels of depression. Clinicians may be able to help lessen the disparity by encouraging hope for realistic and achievable goals.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grant APP570893) and by a seed grant from the Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Katrin M. Sjoquist, Michael L. Friedlander, Merryn Voysey, Madeleine T. King, Martin R. Stockler, Phyllis N. Butow

Provision of study material or patients: Michael L. Friedlander, Amit M. Oza, Kim Gillies, Julie K. Martyn

Collection and/or assembly of data: Rachel L. O'Connell, Merryn Voysey, Kim Gillies

Data analysis and interpretation: Katrin M. Sjoquist, Rachel L. O'Connell, Merryn Voysey, Madeleine T. King, Martin R. Stockler, Phyllis N. Butow

Manuscript writing: Katrin M. Sjoquist, Michael L. Friedlander, Rachel L. O'Connell, Madeleine T. King, Martin R. Stockler, Julie K. Martyn, Phyllis N. Butow

Final approval of manuscript: Katrin M. Sjoquist, Michael L. Friedlander, Rachel L. O'Connell, Merryn Voysey, Madeleine T. King, Martin R. Stockler, Amit M. Oza, Kim Gillies, Julie K. Martyn, Phyllis N. Butow

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section editors: Eduardo Bruera: None; Russell K. Portenoy: Grupo Ferrer (C/A); Boston Scientific, Covidien Mallinckrodt Inc., Medtronic, Otsuka Pharma, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, St. Jude Medical (RF)

Reviewer “A”: None

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Colombo N, Van Gorp T, Parma G, et al. Ovarian cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;60:159–179. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzog TJ, Pothuri B. Ovarian cancer: A focus on management of recurrent disease. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:604–611. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rustin G, Tuxen M. Use of CA 125 in follow-up of ovarian cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:191–192. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackledge G, Lawton F, Redman C, et al. Response of patients in phase II studies of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: Implications for patient treatment and the design of phase II trials. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:650–653. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markman M, Rothman R, Hakes T, et al. Second-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:389–393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, et al. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: A randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3312–3322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle C, Crump M, Pintilie M, et al. Does palliative chemotherapy palliate? Evaluation of expectations, outcomes, and costs in women receiving chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1266–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Gruenigen VE, Daly BJ. Treating ovarian cancer patients at the end of life: When should we stop? Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:255–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Gruenigen VE, Daly BJ. Futility: Clinical decisions at the end-of-life in women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowes DE, Tamlyn D, Butler LJ. Women living with ovarian cancer: Dealing with an early death. Health Care Women Int. 2002;23:135–148. doi: 10.1080/073993302753429013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Post-White JJ. How hope affects healing. Creat Nurs. 2003;9:10–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reb AM. Transforming the death sentence: Elements of hope in women with advanced ovarian cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:E70–81. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E70-E81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballard A, Green T, McCaa A, et al. A comparison of the level of hope in patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi GC. The role of hope in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:415–424. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.415-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herth KA, Cutcliffe JR. The concept of hope in nursing 3: Hope and palliative care nursing. Br J Nurs. 2002;11:977–983. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2002.11.14.10470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rustoen T. Hope and quality of life, two central issues for cancer patients: A theoretical analysis. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18:355–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliott J, Olver I. The discursive properties of “hope”: A qualitative analysis of cancer patients' speech. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:173–193. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:1251–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dufault K, BC M. Symposium on compassionate care and the dying experience: Hope–its spheres and dimensions. Nurs Clin North Am. 1985;20:379–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daneault S, Dion D, Sicotte C, et al. Hope and noncurative chemotherapies: Which affects the other? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2310–2313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrell B, Cullinane CA, Ervine K, et al. Perspectives on the impact of ovarian cancer: Women's views of quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1143–1149. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.1143-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCorkle R, Pasacreta J, Tang ST. The silent killer: Psychological issues in ovarian cancer. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17:300–308. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basen-Engquist K, Bodurka-Bevers D, Fitzgerald MA, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Ovarian. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1809–1817. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedlander ML, Voysey M, King M, et al. Symptom burden in patients with platinum resistant/refractory ovarian cancer–final results of stage 1 of GCIG symptom benefit study (SBS) Int J Gyn Ca. 2011;21(suppl 3, 12):S1–S1372. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson T, Alexander S, Hays M, et al. Patient–oncologist communication in advanced cancer: Predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Supportive Care Cancer. 2008;16:1049–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago E, et al. Giving honest information to patients with advanced cancer maintains hope. Oncology. 2010;24:521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiely BE, Tattersall MHN, Stockler MR. Certain death in uncertain time: Informing hope by quantifying a best case scenario. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2802–2804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiely BE, McCaughan G, Christodoulou S, et al. Using scenarios to explain life expectancy in advanced cancer: Attitudes of people with a cancer experience. Supportive Care Cancer. 2013;21:369–376. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunfeld EA, Ramirez AJ, Maher EJ, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer: What influences oncologists' decision-making? Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1172–1178. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3490–3496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weeks J, Cook E, O'Day S, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;27:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneiderman LJ. The perils of hope. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2005;14:235–239. doi: 10.1017/s0963180105050310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grandinetti D. “Ethical hope”—a lifeline for sick patients. Med Econ. 1999;76:118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picherak T. The 1999 Schering Lecture. Cancer: The long and winding road. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2000;10:50–55. doi: 10.5737/1181912x1025055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Links M, Kramer J. Breaking bad news: Realistic versus unrealistic hopes. Supportive Care Cancer. 1994;2:91–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00572089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mileshkin LR, Antippa P, Schofield P. Stories of the music of hope. Med J Aust. 2012;196:276–277. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, et al. Fostering coping and nurturing hope when discussing the future with terminally ill cancer patients and their caregivers. Cancer. 2005;103:1965–1975. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gum A, Snyder CR. Coping with terminal illness: The role of hopeful thinking. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:883–894. doi: 10.1089/10966210260499078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]